The following article on Miguelanxo Prado’s Streak of Chalk was written about 15 years ago soon after the release of its English translation. It has never been published and I assumed the manuscript had been lost up till a few months back when I discovered it in a stack of old ring folders.

While Prado is probably best known in the U.S. for his work on Sandman: Endless Nights, this was the book which brought him to the attention of Europe and to a lesser extent the American comics cognoscenti. The mid-90s was a relatively fallow period for European comics in translation. They were certainly being released, but in such numbers that Prado’s book seemed like an oasis (this being no testament as to the actual quality of the water). This situation hasn’t changed significantly in the intervening years with a mere trickle of translated works emerging from that side of the Atlantic. A large number of important comics of European origin have never been translated or are long out of print. There simply isn’t a market for them much less any related critical writing.

In the article that follows, I’ve focused largely on the symbols and allegories found in Streak of Chalk but there are a few other elements that bear looking into: the dualism and unity of the two female protagonists; the recursive imagery; and the metatextual elements.

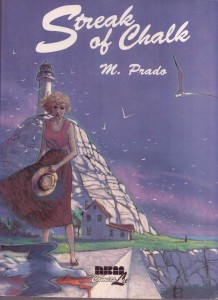

Streak of Chalk won the prize for Best Foreign Comic at Angoulême in 1994.

***

“Bioy Casares had eaten with me that night and we held a grand debate about the execution of a novel in the first person, whose narrator omitted and distorted the facts with various contradictions, which let few readers – a very few readers – forsee a reality either frightful or banal.”

Jorge Luis Borges, Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius

(as quoted by M. Prado in Streak of Chalk)

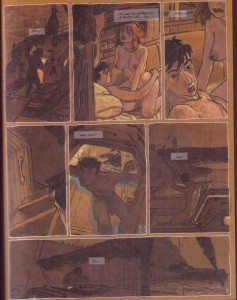

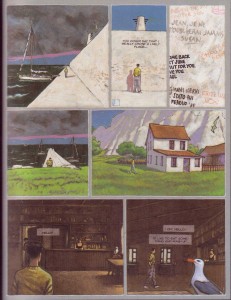

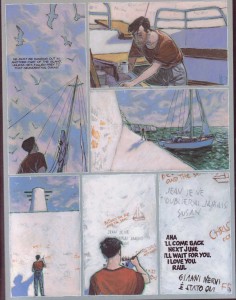

Synopsis. A man called, Raul, is forced into the harbor of a small island by a storm. The island is inhabited by a coarse, voluptous woman called, Sara, and her strangely reticent son, Dimas, who regularly sharpens a set of fine lances which he uses to kill seagulls.

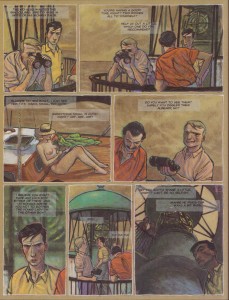

The next day, Raul begins to make advances towards another new arrival on the island, a writer called Ana. He fails miserably in this despite some initial success. He is further confounded by the arrival of two virile competitors named Berto and Tato.

These two men proceed to make unsolicited advances towards the two women on the island. Ana chases them away with some sharp words and, when these fail to deter them, a carefully placed shot from her revolver. Sara isn’t so lucky and is raped. The next day, Berto and Tato have disappeared, presumably killed by Dimas in revenge.

Sara recovers rather quickly from her experience. Raul’s failure to interest Ana leads him to seduce (or be seduced) and bed Sara. Just at that moment, a repentant and solicitous Ana decides to make up for her earlier rudeness with a bottle of champagne. She chances upon Raul and Sara making love, a situation which causes Raul to leave the island in a cloud of shame.

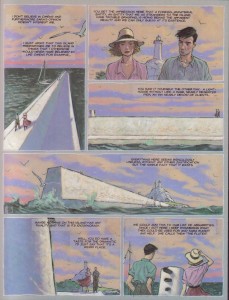

Raul, realizing his overwhelming love for Ana, returns to the island. He finds things much as they were when he first arrived – in fact, things haven’t changed at all. He encounters Berto and Tato, whole and intact, this time salivating over two new women. Sara doesn’t recognize Raul and a message left by Ana for him has disappeared in the process. All Raul can do is leave a message on a wall beside the pier. Ana returns home to write an account of her adventures and in a cynical glance at the world of publishing, her publisher decides that it lacks the necessary sexual elements to sell a book.

***

Poussin: Isn’t it true that these different degrees of fear and surprise form a kind of play which arouses the emotions and gives pleasure?

Leonardo: I agree, but what is this composition? Is it history? If so, I don’t know it. It’s rather a piece of fantasy.

Poussin: It’s a piece of fantasy.

from a dialogue concerning Nicolas Poussin’s

Landscape with a man killed by a snake [1]

The interpretation of Poussin’s Landscape with a man killed by a snake has always posed a problem. Traditionally, it is thought that Poussin visited the city of Terracina and it is thus hypothesized (not to general agreement) that he may have toured “the malarial, snake-infested” [2] marshes near the lake of Fondi. Others have seen in it a meditation on the vagaries of fate and the suddenness and unpredictability of death. It is also generally accepted that there is an element of psychological study amidst the play of emotions represented therein. We have, in Miguelanxo Prado’s Streak of Chalk, a similarly positioned work. When Prado begins his perplexing tale with lines straight from Jorge Luis Borges’ Tlön, Uqbar and Obius Tertius, we are expected not only to take the hint but to proceed down a specified path to enlightenment.

“The allegory is a fable of abstractions, as the novel is a fable of individuals. The abstractions are personified; therefore in every allegory there is something of the novel. The individuals proposed by the novelist aspire to the generic; an allegorical element inheres in novels.”

Jorge Luis Borges, “From Allegories to Novels” [3]

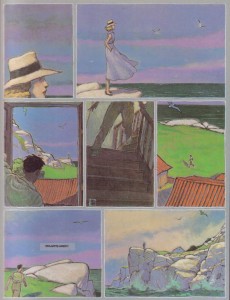

Within the pages of Prado’s book, the characters play out mythical figures in an allegorical landscape. Our journey begins in a latter day Arcadia, a land which has been variously described as the ideal region of rural contentment or the home of pastoral simplicity and happiness. This identification is not derived from any obvious labels but Prado is determined to ensure some degree of comprehension on the part of his readers.

For instance, the set of musical pipes found at the tip of the pier suggest a syrinx and hence the god, Pan, while the unrepentantly lecherous Berto and Tato may be easily viewed as modern day satyrs. On reading Ana’s manuscript at the close of the book, an editor comments on the “great inequality” between the “cultured and refined” Ana and the “wild and intuitive” Sara. This recalls the Neoplatonic concept of an Earthly and Celestial Venus (Venus Vulgaris and Venus Coelestis respectively).

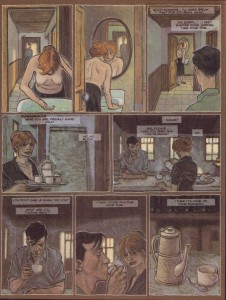

Ana (Venus Coelestis) represents a chaste or divine love, a love aroused by contemplation. As such the relationship between Raul and Ana is never consummated; it is an idealized partnership wreathed with all the flowers of possibility. Sara (Venus Vulgaris) represents something more lustful and materialistic. When Sara attempts to seduce Raul, she stands semi-nude before a mirror washing herself in a somewhat lewd turn on The Toilet of Venus, engendering emotions unbridled by guilt or morality.

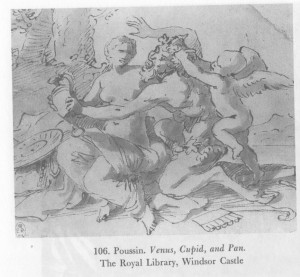

Sara’s son, Dimas, is the physical manifestation of Anteros, the god of reciprocated love or, as in the case of Venus Vulgaris, earthly uninhibited passion. In slaughtering the representatives of of Pan (Berto and Tato), he replays in violent fashion the theme of Omnia Vincit Amor. In Poussin’s Venus, Cupid and Pan, for instance, we see Cupid defending his mother from an attack by a horned and cloven-footed Pan.

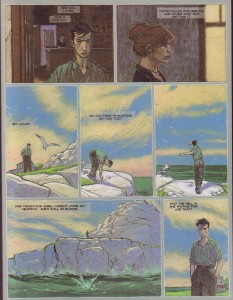

His brother, Eros, is precisely where we would expect him to be – in the air. He is the seagull (Lucas) which Raul encounters in the opening pages of Prado’s tale.

In classical art, any conflict between Eros and Anteros did not represent discord but rather “the strength of their feeling” towards each other. Dimas’ attacks on the seagulls is not merely indicative of his cruelty but also an allegorical representation of the formulation of love. It is only when Lucas disappears (presumably killed) that Raul and Ana begin to long for each other. This murder suggest the triumph of the sensual and banal over the spiritual (as seen in Raul’s final submission to Sara).

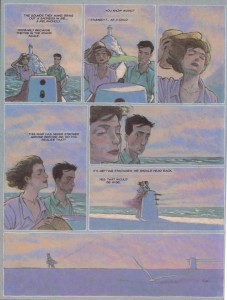

The island’s lifeless lighthouse stands like a herm presiding over a modern day bacchanal. This phallus lodges itself into various panels and on one occasion even interposes itself between Ana and Raul. It is from this high vantage point that Berto and Tato attempt to spy on a nude Ana.

It is said that herms were created for purposes of protection and the delineation of boundaries. They were also sometimes seen as personifications of eloquence and intellect. It is therefore no coincidence that it is upon the pier (the streak of chalk and thus a boundary line in itself)…

…that the lighthouse can be found wedged between Ana and Raul. It is here, on the dividing line of their fates, that Raul and Ana hold their most civilized and intimate conversation.

This flawed Arcadian isle is a timeless microcosm of our very existence. Prado’s story begins with a storm conjured up as easily as that by Prospero in The Tempest but neither that noble sorcerer nor his daughter are anywhere to be found. Ariel remains imprisoned in a pine tree and we see him in the seagull, Lucas [4], who befriends Raul. This is an island still in the grasp of Sycorax (Sara) and her offspring, Caliban (Dimas).

***

“Sometimes they sing, but only for themselves, and their song isn’t a call to others, but a sort of longing lament. They soon get tired and when evening falls they lie down on the little islands that take them about and perhaps falls asleep or watch the moon. They slide silently by and you realize they are sad.”

Antonio Tabucchi, The Woman of Porto Pim

(“A Whale’s View of Man”) [5]

In his afterword to Streak of Chalk, Prado thanks the author Antonio Tabucchi for “two priceless gifts”. The first is a lighthouse without a beacon and the second is a wall with messages from separated lovers written in various languages.

The ineffectual lighthouse comes from a section in Tabucchi’s book which quotes Chateaubriand’s phrase, “Inutile phare de la nuit”. The words may be Chateaubriand’s but Tabucchi appropriates them for his own purposes. He sees his belief in the non-existent light of the lighthouse as a symbol for “the power of illusion”, a symbol that allows us to do things which we had once thought impossible.

Such enterprises entail the possibility of failure and the choice here lies between pining for what could have been or actively reaching out for our dreams. One of Prado’s earliest works is a simple yet strangely touching story about a meeting, after a period of many years, between a man who has escaped into rural contentment and a doctor who has become, not through any particular compulsion, a prostitute. It is a story of unrequited love and choices. These basic concerns reassert themselves in Streak of Chalk.

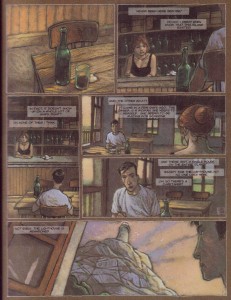

As for the wall, in a story called “Other Fragments”, Tabucchi writes of a cafe called Peter’s bar which is described as “a cross between a tavern, a meeting point, an information agency and a post office”:

“…Peter’s has become the forwarding address for precarious and hopeful messages that otherwise would have no destination. On the wooden counter at Peter’s the proprietor pins notes telegrams, letters, which wait for someone to come and claim them.”

The wall at the pier opens up another possibility if we consider the allegorical theme of The Arcadian Shepherds [6]. Here a group of shepherds (and sometimes a shepherdess) are shaken from their revelry by some words written on a tomb – Et in Arcadia ego (Even in Arcadia I am). The shepherdess in Poussin’s famous painting on the subject is “dressed in a daring decolletage which suggest the amorous delights of the shepherds before they stumbled upon the tomb” [7]. The sudden realization that death is also to be found in seeming paradise elicits expressions of surprise, contemplation and resignation on the faces of the shepherds. In Poussin’s second attempt on the same subject, more meditative expressions can be found upon their visages. The allegory is said to illustrate the omnipresence and and insurmountably of death. More importantly, it has also come to represent a longing for a past golden age or even lost love.

There is more to be gained in relation to Prado’s book from a reading of Tabucchi. In The Woman of Porto Pim, there is a chapter titled “Hesperides” in which the author describes a pantheon of gods “of the spirit, of the sentiments and passions” each with a temple on a different island. Visits to these islands are not merely pilgrimages but emotional experiences. The island of love holds no visible god but it is suffused with an ambiance created by the sound of sea water pushing its way “through a channel carved from rock” producing an “endless echo, rousing whoever hears it and inducing a sort of intoxication or daze”. In this we find yet another meeting of minds between Prado and Tabucchi for Raul and Ana have a similarly intoxicating experience at the pier where sea winds traverse a set of pipes creating a polyphony of pleasant sounds and emotions.

When Tabucchi climbs to the highest point of the island of love, he finds it deserted and that all “the figures and faces of love” he had seen representing friendship, tenderness, gratitude and vanity were but mirages. In the illusory world of Streak of Chalk, where memories are as permanent as words carved in stone and where experiences are as intangible as dreams, all that is left in the end is forlorn hope scrawled on a flat, white wall.

NOTES

[1] Anthony Blunt, Poussin. François Fénelon as quoted by Anthony Blunt

[2] Richard Verdi, Nicholas Poussin 1594-1665. Verdi also indicates that the aim of the painting would have been to “move the soul and emotions of the viewer through the reacions of his figures to a dramatic theme set in an ideal landscape”. A description which could be applied just as easily to Streak of Chalk.

[3] Jorge Luis Borges, Other Inquisitions 1951-1952

[4] The name Lucas is derived from words meaning light or white (the Latin word lucus means “a sacred grove or wood”)

[5] Antonio Tabucchi, Vanishing Point

[6] Strangely enough, Chateaubriand also commissioned a new tomb for Poussin in the church of San Lorenzo upon which a sculptured relief of The Arcadian Shepherds can be seen.

[7] Verdi, Nicholas Poussin 1594-1665

Fine piece — good that you found it again! I only half-remember any details about “Streak of Chalk”, but distinctly recall finding it an admirably ambitious, but at the same time unbearably pretentious and ultimately hollow work. The same goes for its equally horrible immediate predecessor “Tangents”. I like Prado’s earlier work much better.

Just a quick iconographic comment: to Renaissance neoplatonists, Venus Vulgaris is not regarded as “lustful and materialistic” in the way you intimate here, and the love she offers is not one that engenders “emotions unbridled by guilt or morality”. Rather she plays a vital role in the transcendence offered by love: without her, you will never be able to aspire towards her sister, Venus Coelestis. She embodies an acknowledgement of physical existence as a constituent of love.

Amoral, feral love, on the other hand, has no place in the neoplatonist model of transcendence, and is indeed to be avoided if one hopes to realise one’s divine potential.

Since my recollection of “Streak of Chalk” is so hazy, I’m not sure what this means in relation to the book, but there it is.

Hi Matthias, always nice to get some pointers from someone who knows his way around old masters and fine art.

As for the Renaissance Neoplatonic view of the two Venuses, I think it has some bearing on the whole story. I think Prado intends to present a cynical and degraded form of this as evidenced by the reaction of Ana’s editor to the book – a sort of elliptical comment on art and love in modern times.

If memory serves, I think you’re right when you write that Tangents was not very good. Think it was released as a collection in English after Streak of Chalk though the stories in it might have been serialized at an earlier date.

It’s been a while since the last time I read this book. Firstly though I must make an assumption: reading it in English makes for a different view on the writing than it does reading it in Spanish. My recollection of the book (which is, as it may seem, fond) is marked by what I thought was a rather humble style in dialogues, even when reaching rather pompous, methodical demonstrations of intellectuality. Of course, that’s an impression, but the art still gives me that feeling too, which lightly differs from Prado’s other works (such as the wonderful Crónicas Incongruentes) in its transition from details to this diffuse imaging of a timeless world.

Anyway, the direct relation to Latin American literature that is set through the quoting of Borges is an interesting starting point for the analysis of the work. Beyond (or besides) the idea of a distorted reality, Prado makes Streak of Chalk (which title is almost a play on words too in Spanish, Trazo de Tiza) act as some sort of intermediary between the fiction of authors as Borges, who constantly tries to alter his narrative landscape with subtle-then-evident time distortions, the Latin American Boom writers with their cyclic and nonlinear use of time and his own work as a Spanish comic book writer. So I guess it’s a nifty way to set in motion the sense of Streak of Chalk as a mixed work, a probable mestizo.

The translation of that uncertainty is the depiction of hazy backgrounds and faces intertwined with literary references that expose the impossibility of a chronologically satisfying conclusion (for the characters). And the intertextual relationships the work establishes make me think even more that there is a sense of mestizaje conceptually. A discourse on comics as a medium that sees itself partly literature, partly art and that tries to make what it can with both of them. I’m not saying that’s a discussion to take here, just that the work takes a role in it.

I think I can relate that thought to your article too, which is always fun!

There’s a nice article to check on the intertextuality of Streak of Chalk here, by the way!

http://www.uv.es/extravio/pdf4/a_marante.pdf

Thanks for the link, Claudio – I managed to get a bit out of it through a translation program. And your point about Prado’s comic being a “mestizo” of sorts (both in its intertextuality and the way it plays off art and literature)sounds absolutely right to me. It’s an elaborate work which can be read in many ways, but this complexity was given short shrift during its time in the sun (at least in the English-speaking world).

As for your first point, I’ve got a feeling that Matthias may have read the book in French or Danish. Having said that, the narration and dialogue even in the English translation doesn’t strike me as “pompous” at all. I think Matthias may be referring to the thematic content.

Hi Suat;

It’s not exactly as described by Prado, but the wall really exists:

http://www.flickr.com/photos/joe_taruga/314429981/

http://a-little-bit-about-my-live.blogspot.com/

Ditto Peter’s Bar:

http://www.panoramio.com/photo/17310468

Thank you! Could these be the places mentioned by Antonio Tabucchi in his short stories and which influenced Prado? I should probably consult Vanishing Point again to find out since it’s been so long since I read it.

This looks oddly similar to John Fowles’ The Magus — classical allusions deployed in the interest of mythologizing Our Hero’s lyrical horniness.

I do like the way the color palette is used to unify the pages, though.

There are some similarities but not as many mind games or swirls and twists in the plotline. The comic is considerably less engaging than Fowles’ novel. Part of this is down the overall length of the comic which is just too short for any in depth characterization or convolutions in the narrative. I can imagine Streak of Chalk being made into a 2 hour European art film.

The Magus is more about critiquing our hero’s lyrical horniness than it is about lyricizing it. There are some problems with the critique, perhaps (the way in which the book exploits the male reader’s horniness too), but I think these too should be read in terms of inviting and then critiquing the reader’s complicity.

Nicholas Urfe is a jackass, and is meant to be viewed as such…

Yeah; I know you like the Magus more than I do.

In general, if an author is telling me he is implicating the reader, I can be relied on to think it is bullshit.

noah, how is the magus about lyricizing hicholas urf’s horniness?

does anyone in that novel not come off as really dickish by the end, and nicholas throughout?

To be fair, I haven’t read it in a long time.

My impression, though, was that the novel both portrayed him as a dick and romanticized his dickishness.

I mean, it’s a dickishness which is allegorized and strewn about with classical trappings, after all.

“I mean, it’s a dickishness which is allegorized and strewn about with classical trappings, after all.”

that is at least partly true. i should make it clear that i have only read the 1970s version which i’ve heard is different in some ways to the original one (easier to follow is one of the comments i have heard, i don’t know if it’s different thematically though).

the use of classical allegory as i remember it is limited to the involved game that the islanders play on urf, which is partly to flatter him (i am smart and well edjucated and high brow) into getting into the game. you could also insert metaphor about game = life, but that’s the book, ambiguating artifice and reality. yes it’s dickish but i also thought it was philip k. dickish, which is where i came to it from and part of why i liked it.

it’s frustrating that he doesn’t really learn anything or grow by the end of the novel.

about the culpability thing i didn’t see that as much, eric. there is some parallel between the reader for whom the novel exists and the characters for whom the game exists but does that = culpability?

Yes, here’s Porto Pim beach:

http://static.panoramio.com/photos/original/16243396.jpg

Probably too late to bother responding…but the question of whether Nicholas “grows” in the book is a tricky one, insofar as the final encounter between Nick and Alison is “frozen,” leaving the reader with the “choice” (to some degree) of whether Nicholas “grows” or not. This kind of “decision making” by the reader is less clear, perhaps, than the similar gambit he uses in The French Lieutenant’s Woman (a bona fide great book IMO). In that book, the intrusive narrator gives the reader the choice of at least three endings…So, what “really” matters is not the choices Urfe (or Smithson) makes, but the choices (and the failures) of the reader.

Obviously, some don’t like this kind of self-reflexive game playing—but regardless of whether you “like” it, the point is not to celebrate or lyricize the main characters, but to put them through an “awakening” procedure. The parallel procedure works on the reader insofar as we (like Urfe and Smithson) are led through a series of blind alleys, interpretations, and “revelations” that we experience (supposedly) as he does. Obviously the relationship is not 1:1, but that’s definitely part of what both books are up to.

The greatness of FLW is that despite the fact that it too is laden with “snooty” quotations, etc., it also works as a rollicking good read–a page turner of a Victorian novel, along with the more “postmodern” or “existentialist” trappings. One never works to screw up the other–and the high-falutin’ philosophical business is never as intrusive as it is in The Magus (a book I also like)

hi eric, not sure if you’ll read this but i appreciated your response. yeah, i liked the magus a lot too. i picked up a copy of the french lieutenant’s woman a while ago but just haven’t gotten around to it yet.