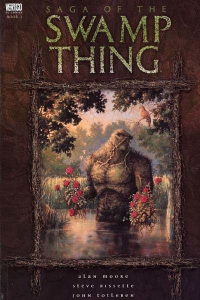

My friend Chris loaned me his beloved, carefully encased in plastic, original issues of the full Alan Moore run of The Saga of the Swamp Thing for this roundtable. We’ve been talking about it off and on for the last couple weeks. This post is compiled from the highlights of our conversations.

My friend Chris loaned me his beloved, carefully encased in plastic, original issues of the full Alan Moore run of The Saga of the Swamp Thing for this roundtable. We’ve been talking about it off and on for the last couple weeks. This post is compiled from the highlights of our conversations.

Chris: Well, they weren’t carefully encased in plastic.

Caroline: No? You couldn’t prove it from how hard they were to get out.

Chris: I really do hate plastic bags. I typed a mini-rant that was totally off-topic, but you know, I’m not that much of a geek.

Caroline: You couldn’t prove it from this blog post.

Chris: Ha ha ha. Very funny.

Caroline: Well, I haven’t gotten them back in the plastic yet, but thanks for loaning me your Swamp Things.

Chris: You’re welcome. Did you like them?

Caroline: I did!

Chris: Really? I didn’t expect that. I never once thought about trying to hand you any Alan Moore other than From Hell.

Caroline: How come?

Chris: Well, they’re just pretty much straight-up genre work for the most part, albeit a kind of elevated version of it.

Caroline: Hey, I like genre!

Chris: You like SF.

Caroline: And romance!

Chris: OK, yeah, but you hate fantasy, and I’ve never heard you say anything about horror.

Caroline: Well, ok. That’s true. Sort of. I don’t absolutely hate fantasy and horror; it’s just that I don’t much like their post 19th-century incarnations, except when they’re really intended for kids. I like them fine in mythology or actual Arthurian legend, or Mary Shelley.

Chris: When I’ve steered you toward stuff, I’ve gravitated more toward the art than the genre side. Genre comics are books where the whole point is “this book exists to be liked,” and you tend to want more than that.

Caroline: Well it’s no secret how much I love art fiction. But I just read genre fiction differently from how I read art fiction. I’m less intellectually interested in it but it’s still pleasurable.

Chris: I guess I’m surprised you liked Swamp Thing because a) I didn’t think you were interested in genre fiction more than historically, and b) I think the problematic thing about SotST is that it kind of smacks of trying to redeem genre. You know: “World’s Best Swamp Creature Comic.” Everybody seems to struggle with “b”, and I didn’t think you would be any exception. But I didn’t think you’d get past “a.”

Caroline: Well, here’s the thing. I’m sure one of the reasons I was able to like this one is that the activation energy was very low, largely due to the prose doing the heavy lifting on the story. I could skim it. I can’t skim an art comic. I’m not sure anybody can really skim an art comic, at least not while actually “reading” it.

When I read genre, it’s for relaxation and the point is just to get swept along and enjoy it, not to really wallow in the details. I guess I read it like most people watch tv. Remember that reading for details is my job. So when I read for entertainment the whole point is not to worry as much about details, except the ones that I need to understand what’s going on.

So I especially like genre fiction that really wallows in familiar tropes. If it gets experimental or tricky, I want it to be something with a lot of metaphorical sophistication, really more art fiction that’s playing with genre tropes than “well-done genre.” I don’t have the energy for some really thick plot-heavy worldbuilding thing, because then I have to pay a lot of attention for a payoff that essentially is only a decent story. And mostly I’m not interested in thinking very hard about stories. I kind of expect a story to resonate enough that I don’t have to.

Chris: Hm. I can see that.

Caroline: And hell, this Swamp Thing is the uber-incarnation of “wallowing in familiar tropes.”

Chris: I was just going to say…

Caroline: I could read through it pretty quickly, enjoy the atmosphere and feel grounded enough to know what the story was, but not really be obligated to dig into the details.

Chris: Although, “wallowing in tropes” applies mostly toward American Gothic, which has this artificial structure imposed on it…

Caroline: I don’t know about that. I think Moore takes tropes from different genres throughout. The romantic triangle with the jerky husband is very much a trope, then Abby falling in love with her best friend. There are science fiction tropes throughout, and some elements from noir interspersed, especially in Constantine. Everything was quickly recognizable. I didn’t feel like anything was particularly new.

Chris: Let me talk to your prose observation…You like it because it’s prose for all intents and purposes, but you said you did like the art, yes?

Caroline: Absolutely. It’s very lush and atmospheric. I love the colors.

Chris: Does the art just provide atmosphere? Does it contribute in any meaningful way, or is it just a substrate for Moore’s prose?

Caroline: Well, atmosphere is a big part of genre isn’t it?

Chris: Yeah.

Caroline: I think it mostly provides atmosphere and texture, but I think that’s essential to good genre. It happens to be the part that’s often not very effectively conveyed in prose, and art gets at it very efficiently. I thought this art was smart and mostly very consistent at a high-level with Moore’s aggregation of tropes. I’d probably even say the art overall was better quality than the writing; it was a huge part of the impact of the book.

Chris: I think one of the interesting things about Swamp Thing in this respect is that it is a collaboration. Bissette-Veitch-Totleben were pals and studiomates, so there was a more seamless union than you usually get. Generally penciller/ inker breakdown is just assembly line to grind out more product faster. This team, all of them were pretty simpatico.

Caroline: That makes sense. There was a tremendous difference in the issues that had a different art team: they weren’t nearly as alive. They really didn’t have anything like the same emotional texture. But I guess what I’m saying is that I wasn’t really relying on the art at all to make sense of the book.

From my perspective, as a very skilled fiction reader almost entirely unfamiliar with mainstream comics, the division of labor here – meaning the narrative labor, not the collaborative work of creating the book – is very sensible and practical: the words did the narration and dialogue, the stuff words are really good at, and the pictures set the atmosphere and the tone and the mood, created the emotional texture. And the prose is just really competent: the prose techniques and tropes were very recognizable, and that was a really easy way into the story.

And an easy way in was really essential for me as a first-time reader. The few times I’ve picked up mainstream comics before, I’ve immediately had a very strong sense of “this was not written for me.” There’s a hint of “go read these other things and get a grounding in this tradition, then come back and read this,” which requires a commitment to genre comics that I don’t have. That wasn’t here at all in this book, despite the strong genre tropes, because they were so immediately and totally recognizable from their fiction counterparts.

Chris: I think the art really does contribute maybe more than you’re implying, because the team was so sympathetic, both to what Moore was doing, and to the genre in general. I think Bissette was overjoyed to be associated with “Best Swamp Creature Comic Ever,” without irony or embarassment.

So if SotST had been drawn by whomever was just hanging around the DC offices looking for work, I don’t think it would have been the same, no matter what the caliber of writing. Steve Bissette in particular is BIG into horror, and I think his enthusiasm was kind of a driving force in a lot of ways.

Caroline: I don’t disagree with that. I’m not so much trying to downplay the art as explain how the prose worked for me. My point is just that I didn’t really find myself reading the art much. And really, my overall response to the comic wasn’t that the horror genre was so dominant.

Chris: Even in the art?

Caroline: I saw a lot of visual tropes from horror in the art, but there were so many other genres mixed in there that no single one ever rose to the surface. Constantine’s clothes: so noir. I recognize that the horror genre was the one they riffed on most explicitly in the American Gothic section, but the atmosphere, almost entirely coming from the art, really didn’t feel like a Friday the 13th movie or even horror from the 50s/60s like The Blob.

Chris: I think that effect – so much genre there’s a lack of genre – is Moore’s big contribution. American Gothic was probably a self-conscious attempt to “redeem” horror tropes, and I think it generally reads like a creative writing assignment (except for the zombie bits that I really love and we can talk about later…) Before that, I think the horror was more interesting, more organic, more free floating… it could seep into the story as needed.

Caroline: Exactly; it’s organic in form and content – which I really dug because it was so thematic.

Chris: Yeah, me too. I think that was on purpose: fecundity as motif…

Caroline: No doubt. I loved the way the idea of organicism was this overarching conceit for the first part, in the imagery, in the storyline, and then also in the way the different story elements were integrated together. In many ways it’s a very non-linear tale – at least, for mainstream genre.

Chris: Sure. And, you know, why shouldn’t a Swamp Creature comic demonstrate a high level of craft?

Caroline: This makes me think of Noah’s comment from early on, and I think Suat’s too, that they’re “massively massively overwritten.” That sort of implies a lack of craft, doesn’t it?

Chris: I suppose so…

Caroline: I guess, like I was saying at the beginning, I didn’t carefully read and commit to memory every textbox, so I’m sure there were particularly purple passages that I completely skimmed over. But I don’t think I’ve ever read a true work of genre fiction with that careful close reading. I’m not sure what the payoff of spending my time that way would be. I read Zizek that way, but not Heinlein.

Chris: There were passages and lines here and there that made me cringe… but overall, I thought he had a good batting average.

Caroline: Flipping back through it and looking at people’s examples, there are definitely purple passages, but they just didn’t bug me because I wasn’t reading at that grain. I was trying to hold on only as tightly as it took to stay on the ride.

Most just didn’t strike me as overwritten, although the example Noah comes up with really is pretty egregious:

“the interminable, tortuous extended metaphor comparing the emergency care ward of a hospital to a forest is probably the absolute low point of this volume— “in casualty reception, poppies grow upon gauze, first blooms of a catastrophic spring…a chloroform-scented breeze moves through the formaldehyde trees…”

What do you think, can we defend that on the “fecundity as motif” grounds?

Chris: I would say yes.

Caroline: OK. But it probably works because of the tightness of that fecundity/organicism metaphor. I’d say the whole thing may be a little overgrown, but that’s kind of the point…

Chris: I’ll offer an example of a kind of overwriting that I think would irritate you: Hellblazer, the John Constantine spin-off. I haven’t re-read it in a long time, but it also used a very florid prose style. But to me, it seemed more like a coat of paint slathered over the story.

Caroline: That’s a good way to describe what I felt about this one. There was definitely purple prose in places, but it was like a bad paint job, not a rotten board.

Chris: I don’t think that’s quite what I mean. With Jamie Delano, who wrote Hellblazer, the purple stuff is all on the surface, it really detracts from the overall effect. Even when Moore’s at his most purple, I don’t think you’re intended to take the overwriting seriously: it all just seems very playful. Delano was (in my hazy memory) utterly humorless, and that made his writing really insufferable to me.

Caroline: I see where you’re going – with Delano, there’s an earnestness to the purple prose that makes you sort of laugh at him. With Moore, it’s like a Magic Kingdom ride through genre fiction with a somewhat outlandish character on the loudspeaker. Set in a swamp.

Chris: Talk about purple prose.

Caroline: I try.

Chris: But yeah, Delano struck me as “earnest angry young man in coffeehouse.” (I don’t want to rag on him totally. Hellblazer did have some good long term character development in it, but man, was it a slog to get through…) But Moore is very freewheeling, libertine. A little like Sam Delany.

Caroline: I’ve been on this Delany kick lately.

Chris: Yes, I know.

Caroline: Pfft.

Chris: It reminds me of that sequence I keep pointing out in Motion of Light in Water. I should maybe pull the quote, but basically, Delany talks about the ‘60s, and how the era crystallized for him as he listened to a Motown song: The song – with all the typically slick Motown production – was just full of callouts and references to all kinds of other things in music and in culture; it was kind of a smorgasbord of stuff from the larger world just distilled into 3 minutes of pleasureable pop. And Delany noticed from there that that was happening all over the place at the time. “Nothing was forbidden,” so to speak. It informed his writing and his life.

Caroline: Right, Moore is working with what is really not a single genre, but ALL the major pop genres in aggregate. But do you think he’s imposing this ‘60s sensibility onto the book?

Chris: I don’t know if it’s specifically ‘60s; Delany perceived it as ‘60s. I don’t know that Moore necessarily did/does. But a similar sensibility, yes.

Caroline: The yams are pretty psychedelic – and the yam sex sequence is very psychedelic, visually and conceptually. But the book is, of course, from the 1980s. I guess I think that in some ways, there’s a “visual history as trope” in the book. The colors are very ‘70s; the horror images do have a little bit of a ‘50s feel to them, the teenagers in the car especially; the ‘60s psychedelia. The scene in #20 with the gunmen standing around the shot-up Swamp Thing looks a little like 1940s-era military images. There’s nothing I’d really identify as ‘80s but it was early in the decade…

Chris: Well, Constantine is Sting…

Caroline: There ya go.

Chris: There were punk vampires and some side characters, too. The spirit is hippie-era, but I guess it’s a bit punk-era too. That sort of “try anything” ethos…

Caroline: The hippie feel definitely dominates the punk feel to me. The art doesn’t feel punk.

Chris: You don’t think so? Well, I guess not like Gary Panter or anything like that.

Caroline: This is some seriously skilled art. Bissette is not the Sid Vicious of cartooning.

Chris: True.

Caroline: Constantine is really Sting?

Chris: Supposedly. Bissette was a fan and just liked drawing him. It fell by the wayside by the time he got his own book.

Caroline: So he wasn’t doing anything with the fact that it was Sting. Sting was just the model for the physical character.

Chris: Yeah. I’ve always loved the way Constantine sort of knows everybody, from bikers to nuns to boho NYC artists to geeks to friggin’ Mento from Teen Titans. The way he sort of flits from world to world is very much in that Moore-Delany cosmopolitan spirit.

Caroline: Right. “Libertine” applies to Constantine in a slightly more conventional sense. But it’s all held together by this notion of being unrestrained. I suppose that’s ironic, but it’s a very playful irony. Worlds in this comic are very permeable, boundaries are very fluid and overlapping. Nothing’s discrete.

Chris: Characters, history, geography, genre. I’m impressed by Moore’s willingness to play genre mash-up. The most significant example of this is horror + heroics. I confess I’m not a horror guy, so I’ll cheerfully be corrected by someone who knows better, but it strikes me that horror protagonists tend to be victims, passive characters. Moore’s reimagining of Swamp Thing, post-Anatomy Lesson, casts him as an active hero. While the JLA commiserate up in their satellite HQ on how useless they are against Woodrue, who is down on earth (get it?) plowing through the muck (get it?) getting things done? Moore’s Swamp Thing is active, but he’s not the bad guy. He’s defined as a hero and an individual: “This is what I can do. This is how I am unique and where I can make a difference.” Or to use a direct quote: “I am in my place of power… and you should not have come here.” I must confess, I hadn’t reread these for some time, and while I vaguely remembered that Swampy-Arcane battle that included that line, I’d forgotten just what a can of whup-ass Swamp Thing unloaded there. It was awesome, and I mean that seriously. It’s heroics and horror… shouldn’t awe be a basic ingredient? I think it should, but, say, in a typical Justice League comic – it’s just not there. Moore gets it. He remembers to put it in.

Caroline: So this sense that things are libertine and unrestrained works from the perspective of someone coming into the book from the comics tradition as well as for someone like me, coming in via more general genre fiction. The expectations of people familiar with comics are equally muddied up.

Chris: Absolutely. You know, I think the perfect illustration of Moore’s take on genre appears in the Voodoo/Zombie 2-parter. I think some of the most perfect moments in Moore’s run are in that episode. The zombie bits really sing (for me, at least), and I really love the little moments that play against genre expectation in touching and logical ways.

Caroline: I was particularly keen on the first page of that, where he’s detailing the claustrophobia and tedium of “life” in the grave.

Chris: Yeah, you can argue that it’s Moore showing off his prose for its own sake…

Caroline: Wait, you really think it’s particularly prosaic? I didn’t really get that.

Chris: Well, it’s mostly prose. The pictures are just there for the punch line, when he rolls over onto his side: “He couldn’t sleep.”

Caroline: True.

Chris: But I think this imagining of the zombie POV pays off nicely down the road. When the dead father appears before his (now) middle aged daughter, we don’t get the standard “I will eat your brain” sequence, just a father-daughter reunion that is genuinely touching.

Caroline: Yeah, “touching” usually isn’t an emotion that shows up in zombie stories.

Chris: And when the walking dead is still walking by the end of the book and has to get a job, our hero gravitates back toward enclosure, and takes tickets at the local movie house (where the horror movie posters all look absurd in comparison). Come on! That’s funny!

Caroline: It’s that unrestrained permeability again. The undead are usually pretty non-human, but he humanizes them to great comic and emotional effect.

Chris: That’s what works for me: Moore inhabits the horror. He imagines himself as the zombie. The pathos is earned, the emotion is real, the absurdity wittily acknowledged. It’s drama and humor both. Straight-up horror would have bored me. It kind of did, in much of the rest of Gothic. (And generally, only during Gothic, and its plastic conception; not so much pre-Gothic). But Moore’s zombie arc is a sort of mini-masterpiece of sympathetic writing and willingness to dance outside the grave. It’s very polymorphously perverse…

Caroline: That’s such a great phrase. The polymorphism is a huge theme in this book and it’s present at every single level. That’s extremely satisfying to me, even from the “art reading” perspective.

There’s a couple of ways to think about it, I guess: you can think of mainstream comics as their own subgenre of genre fiction, like science fiction or romance or horror, with their own tradition and their own tropes. Or you can think of them as expressions of the same genres that you have in fiction, so that science fiction comics and science fiction novels and science fiction short stories are all instances of science fiction. I think Moore definitely went for the latter approach in this book, although he apparently also paid attention to the comic book tradition and tropes.

So the book is polymorphic in relation to these two ways of situating itself – I gotta say that even though I don’t think Moore was really showing off his smarts here, it really is smart how even at that very topmost almost meta-writerly level, he’s still consistent with his surface-level content and themes.

Chris: Moore recognizes that it’s all story: horror into superheroes into romance into comedy into “mainstream fiction.” He respects them all and, at his best, promiscuously blends them into one another with a true libertine spirit. The Swamp Thing–Abby romance is appropriate: breaking taboos and cross-kingdom pollenization – because why not?

Interesting! But concerning the zombie 2-parter: if I remember correctly, the bulk of those 2 issues was taken up by slavery and interracial/gothic romance plotline. I liked the zombies as well but the rest of it killed it for me.

I was a little startled that you liked this as well, Caro. It’s interesting that you didn’t find the cross-over aspects disturbing or off-putting; it’s hard to tell how open-ended, say, Batman’s appearance is or Zatara’s Adam Strange’s when you do know all the characters already. For exmaple, even that vegetable green lantern is an old dc character — but obviously you didn’t need to know that to liek the story.

I think seeing fecundity as a metaphor for Moore’s art is pretty brilliant. There definitely is a “throw everything including the growths in the kitchen sink” in there aspect to the story. It’s nice too that you seem to like it precisely because of the limits of its ambition, or its lack of interest in being especially coherent (part of what threw VM off, it seems like.)

Have your read Watchmen? I’m curious what you’d think of that. Maybe if Chris has them in plastic bags….

________________

“but it strikes me that horror protagonists tend to be victims, passive characters. ”

This is somewhat correct, kind of depending on just which part of the horrorverse you’re in. In slahers, there’s usually a “final girl” who beats the baddy actively. In something like the Thing, there is a hero, though it’s unclear whether he wins.

Generally, horror is a lot less anal about restoring order than super-hero comics are. In super-hero work, the good guy has the power to solve problems, and those problems get solved. In horror, the good guys are much less in control, their victories are less assured and more provisional. A good rule of thumb is that super-hero pleasures are sadistic (in the sense that the enjoyment is in fantasies of empowerment) and horror pleasures are masochistic (in the sense that the enjoyment is in fantasies of disempowerment.) Of course, sadism/masochism are two sides of a slash thingee, so there’s some back and forth…but I have to say I haven’t seen very many mash-ups that really combine the two effectively (I’m iffy on how successful swamp thing is here…when it works it tends to be despite that particular mash up rather than because of it, it seems to me.)

One of the most effective super-hero/horror mashups to me actually may be Friday the 13th part 7, which has this girl with psychic powers fighting Jason. It functions pretty much exactly as a friday the 13th movie generally does, with the added bonus of psychic super powers which makes the end kind of more visually exciting/funny/entertaining. Part of the deal is that the person with super powers is this scared young girl who doesn’t know how they work exactly, so she manages to be more vulnerable than an established hero like superman or even swamp thing could be.

Probably more than you wanted to know about that, but there you are.

I like your S&M analysis, Noah. I think that’s why Swamp Thing doesn’t much work as a horror comic. I’m thinking of Silence of the Lambs versus Hannibal. The latter is actually something of a superhero tale, because the audience identifies with the superpowered Lecter.

If there’s any place where the art really contributes something extra to Moore’s story, it’s in creating whatever sense of horror the book possesses. But I’m one of those horror fans who believes movies do it best. Language, particularly the purple colored, is always too abstract for the genre, and ultimately a distraction from the emotive core. Horror is perceptual, the less said, the better. We can be morally outraged by reading a description of a rape, of course, but seeing it (say, in Irreversible) is on a whole other level, regardless of how well-written the description might be. Language alone allows for more of a sense of control than being submerged in sound and vision. Does that mean language is sadistic and perception is masochistic?

And, as always, my post will show up sometime in the near future.

Hey Charles. I like the idea of language as sadistic and perception as masochistic. I’m wondering how that syncs up with Lacanian theory, but don’t know enough about Lacan to figure it out myself. Would the Symbolic be sadistic and the Real masochistic in that case? Maybe Caro can tell me….

Also…do your comments always get caught in the spam filter? And why on earth would that be?

Zizek writes alot about Lacan in relation to Hitchcock. There’s at least two Zizek books that take that tack–so there’s probably some attempt to talk about horror in Lacanian terms there.

Lacan gives me a headache, but I like Zizek and Badiou. Language as violence has been a pretty common refrain since the 60s, following the analytic “linguistic turn” in the first half of the century, which would tie into the metaphor here, maybe. Someone like Badiou rejects that kind of thinking as sophism. But perhaps Caro can shed some light on Lacan’s take.

Damn it, Charles, your stuff does always get caught in the filter. Why? Stupid wordpress….

There’s a lot of talk in film theory about sadism which I’m trying to get my brain to reaccess…basically voyeurism is equated with sadism, I think; seeing is controlling, denying the humanity of the person being seen (usually a woman.) That would sort of go against the firm distinction Charles is drawing about perception as masochistic, I think…

Geez, I try to write a lighthearted thing about how much fun this comic was and you guys turn the comments to Lacan!

I love you guys.

Sadism and masochism aren’t opposites in Lacan: masochism is a primary symbolic state, and sadism is the displacement of masochistic pleasure onto the body of the Other. (That’s how you get the “erasure” of Woman in the logic of the gaze.) So sadism is always sado-masochism.

I don’t know whether that helps here, at least not in the strictest Lacanian formation. I think a strict Lacanian reading of horror tropes would fixate on the ways in which the victim and perpetrator of the horrific acts were locked in that narcissistic power relationship: either the horror arising from the erasure of selfhood that comes from being made the Other that takes on the sado-masochistic monster’s pain for his own pleasure, or the horror located in the perversion of the monster, a sort of inverse of the empathy-horror dynamic we were discussing the other day, where the horror comes from the idea that “I too could be this monster.” It’s just that everything’s perverse in Lacan from the get go, so horror is in many ways the least perverse expression in genre, because the psyche is always already horrified by the aporia of the Real.

I think that’s what horror films are getting at: just the threat of an “encounter with the Real” in the form of murder or dismemberment. That’s not so much the trick to horror in comics, as Richard pointed out last week.

I’ll have to think about sadistic language and masochistic perception. I’m sure it’s not going to be quite that binary in the strict sense, although there may be some insights gained in making the analogy that would help get out of that narcissistic circuit the strict Lacanian reading puts you into.

Sadism and Masochism are both objects of the invocatory drive, so they will have originated in the field of the subject, which will make them both Symbolic. Perception is mostly Imaginary, while language is Symbolic (or rather, the Symbolic is Language), and it’s the circuit of the drives (the metaphor for psychic recursivity, like nostalgia!) that generates the field of the Subject in language. This includes all the grammatical tenses, including the passive voice, so that even masochism, by virtue of its generation by this active circuit, isn’t passive in Lacan: it’s one of the mechanisms by which the always already perverse Subject can traverse the pleasure principle. (For the Zizekians, this Lacan, mostly from Seminar 11, shows up a lot in The Plague of Fantasies.

I still think there might be something to the analogy though, in what Charles said. The invocatory drive, along with the scopic drive, is associated with desire in the mathemes (as opposed to the oral and anal drives which are associated with demand.) And desire and demand are more discrete from one other than most things in Lacan. But the mathemes are HARD and I can’t do that off the top of my head…

Yeah, I understood maybe a third of that I think.

What’s the invocatory drive? And as long as I’m asking for the moon, what’s a primary symbolic state?

I know that sadism and masochism are often seen as closely linked. I’ve read some things which try to separate them as well, though…is it Deleuze that argues strongly that they’re opposed? Can’t remember, alas….

Short answer: invocatory drive is the drive associated with the voice, as opposed to the scopic drive which is what film theory used for the theory of the gaze. I cannot rehearse from memory why it’s a way out of the recursion of the death drive/pleasure principle, which I’m sure is what you’re really asking…I’ll have to dig out the book.

By “primary symbolic state” I just mean that it’s logically primary, particularly relative to sadism which is secondary, derived from masochism. I probably should have used “the” instead of “a,” but it’s just that it’s not THE primary symbolic state; it’s one of many. The important thing is that it comes before other things, not that nothing comes before it (because things do: like the Imaginary).

Really, it mostly matters because it’s one of Lacan’s reversals of Freud: Freud thought that sadism was the active and masochism the passive forms of the same perversion, but he gave psychic primacy to action and associated the oral and anal stages with sadism (oral-sadistic and anal-sadistic). Lacan does away with the sadism analogy there and replaces it with the language of demand, which is how he talks about drives: the circuit of demand and desire.

I think you’re right about Deleuze. Deleuze’s use of oppositions always made his thought really hard for me — it’s not polymorphous enough! I’d have to look it up too to be sure, though…

I probably also should not have said “before” — let me qualify that there is no linear temporality in the Lacanian topology…so it’s logically before, not temporally before. The Freud is temporal and developmental, so that’s another way in which it’s a reversion.

Still not sure I get all of that; my Lacan is very weak. What is a drive associated with the voice — or I guess, what is a drive in this case? Are we talking something like Freud’s death drive?

In Freud, masochism is about an incestuous attachment to the father — it’s a desire to suffer or take the position of the mother in order to have the feel the father’s power working on you in an acceptable way (more or less.) Deleuze thinks that masochism is a way to undermine the father by taking the position of the mother; a rejection of patriarchal power rather than an embrace of it.

It sounds like for Lacan masochism would be first about the mother or powerlessness, the primary desire being for self-erasure, which is then projected onto others as sadism (you identify with the other, and therefore wish for his/her erasure). That kind of works interestingly in something like The Thing, which is about identity dissolving certainly. Not sure how it works with Charles’ perception as masochism exactly; though you do get perception before language in that case, which is kind of fun. I guess you could see perception as more unitary, less divisive, so that you are equated with reality more seamlessly and therefore are more non-existent. In that case, the sadism of language is in making distinctions; language becomes castration — and I think there’s a Lacanian link between the symbolic and castration, isn’t there?

What this has to do with the super-hero genre would be fairly unclear though. Super-hero = god with implications of creating the symbolic? Which is why Superman has an S on his chest.

Or something.

OH! Oh God, that’s a really hard question. The Drive is one of Lacan’s “Four Fundamental Concepts” so the only way it’s ever represented consistently is in the topology. Yes, all drives are death drives for Lacan, because the drive is the thing that’s produced when the signifier “bars need,” that is, when the “fall into language” creates the Subject. The drives (there are actually four of them, because no single drive can account for the entirety of human need and desire) aren’t the same thing as need, though: whereas the “aim” of a need is to be fulfilled, to get it’s object, the “aim” of a drive is not to get to the object, but to circle around it, just to follow the path of the closed circuit, over and over.

This is Lacan being a stricter Freudian than Freud. Freud made a distinction in German, between Treib and instinkt, but allowed the Standard Edition to translate them both as “instinct.” Lacan maintains the distinction between “drive” and “need” and maps them onto the orders: Need is to the biological organism as drive is to the subject; need is Real, drive is Symbolic.

But the symbolic has no biology: it’s entirely linguistic. So the analogy is very vague: what does it mean for a word, a grapheme, a phoneme to need?

Lacan answers that differently at different points in his teaching, and I’m not sure which one makes the most sense here. The invocatory drive specific relates to the demand of the Other, which is one way that Lacan describes the motivation for entering the Symbolic and becoming a Subject: a hungry baby has to cry for food, because he can’t feed himself, but someone has to care for the baby to provide food, so the cry is demanding both food and love. But although a baby can get enough food, the desire for love can never be fully satisfied.

That cry is the “birth” of the Subject in the Symbolic: speech separates the self from the (m)Other, “bars need”, creates this “invocatory” drive, and leaves an unsatisfied desire as a remainder.

I don’t think any of this is particularly useful directly for understanding superheros (or any other Symbolic construct). You’d have to go up a level, to the articulation of how fantasy formations work, to get material that’s both strictly Lacanian and directly useful for interpreting stories. That doesn’t mean the analogies with sado-masochism couldn’t work, but I’d have to think through it. What you’re saying feels more Freudian than Lacanian to me, but it might just be lingo.

I’m thinking that probably doesn’t help. I can come back to this and try to come up with something clearer and more cogent…

I’ve missed replying to a bunch of stuff people have said in these comments; I’ll try to get to everything tomorrow!

Correct me if I’m wrong, but didn’t Lacan come into this through Noah’s reply to a point that Charles made about horror in text versus film–even though Caro clearly pointed out, and I fully agree, that Swamp Thing isn’t really “horror”? (It never was, from its Wrightson/Wein beginnings… It’s a monster superhero book playing occasionally with horror tropes.) So get off Lacan already!

In any case, Caroline again gets it right, that’s all I wanted to say.

Coming from a cognitive science background, I’m always a bit ashamed when psychoanalysis enters into any discussion I have. I’m blaming Noah.

“get off Lacan already”

I don’t know what Lacan would say about that phrasing, but I believe Freud would stroke his beard….

See, and your shame is also very interesting. Or as Thompson would say, “very interesting.”

Pingback: I Heart Comics: My First Comic « Comic Book Daily

I’m still waiting for you to cave and read All-Star Superman.

Hi there! A friend told me about your Swamp Thing discussion and I’ve really enjoyed reading the dialogue and responses. Although I know very, very little about Lacan and can’t comment on that part of your conversation, I’ve written on the zombie storyline from “American Gothic” for a forthcoming essay collection that reads the two issues alongside neo-slave narrative conventions.

One of you stated that “Moore’s zombie arc is a sort of mini-masterpiece of sympathetic writing and willingness to dance outside the grave.” I fully agree that Moore’s motives are masterful, even if the execution is a little uneven. You may have already mentioned this, but did you know that Moore considers the zombie storyline to be one of the weakest of his entire run? Ironic!

I’m really fascinated by what Moore is attempting in “Southern Change” and “Strange Fruit” (and in American Gothic more generally) by asserting Southern history as monstrous and by using the institution of slavery as a source of soul-possessing horror – even for those who are NOT southerners, but merely step foot on the land like the soap opera actors do.

My only disappointment is that despite Moore’s efforts to empathize and place the reader within the bodies of former slaves, his representations of black characters lack the kind of complexity that Moore is capable of. The zombies have more depth than the living black characters – who are merely types – the Black Nationalist, the mammy figure, and so on. But it’s still an inventive use of EC Comics style horror and I agree that it is one of the most intriguing stories of the series.

Thanks for your posts! Really enjoying it!

Hey Qiana. Thanks for commenting.

I’d guess that Moore’s discomfort with the story has to do precisely with the stereotyping that you point out. Even though there are other aspects of the story that work quite well, you can see where that particular problem might make him (or others) downgrade the whole effort.

Is the essay collection focused on comics in particular?

Hi Qiana — thanks so much for joining in! I wanted to write something about the African-American characters/subplot and just couldn’t work it in so I’m really glad you brought it up.

I’m inclined to think it might have been intentional that the zombies are more “alive” than the living black characters: I think it’s a gesture at a metaphor that he doesn’t doesn’t quite get worked out.

I’m thinking of the “job description” of the zombie when he goes to the movie theater: “a long stint without a meal break or a bathroom break” in a job that “a lotta people can’t take.” Chris is definitely right that the stronger implication is of the zombie trying to get back into the security of the little box, but there are definitely overtones of the working conditions for slaves.

So I think Moore was trying to get at a conceit that combined the idea “slavery burned through people like they were already dead” with the idea that the legacy of that for living black people is a diminished set of possibilities for fully realized humanity. But it’s suggested, rather than fleshed out (no pun intended), so overall it’s not really successful. But the elements are there. I think it’s a pretty remarkable failure.

Gene, all I have to say about Superman is that I completely and totally agree with our esteemed host. But you know that already.

Oh, pooh. Don’t listen to Gary! What you need to read is not All-Star Superman but some good Mort Weisinger-era Superman–such as “Best of the Sixties”–or for that matter the collection of Bizzarro tales from the same period. Then we can talk.

I like the way you describe the contrast between the zombies and the living black characters, Caro. It’s too bad Moore didn’t get that across more clearly. But it certainly suggests a new way to interpret the final image of the black actor, stricken and mute (like a zombie?).

Thanks for the feedback, Noah. The essay is for a collection that focuses on representations of the South and southern history in U.S. Comics. Publication is still about a year away. (I’m one of the co-editors – shameless plug!)

You should send me a copy; I’d be interested to review it. My email is noahberlatsky at gmail, if you want to write for my address.

Suat, if you’re still paying attention, I’d be curious to know what you didn’t like about the slavery/interracial elements. I didn’t get very far figuring out what the point of the gothic romance was: I think you’re exactly right that it’s gothic romance, though.

Qiana, I think the man in the theater box is supposed to be a zombie: he’s the father of the “mammy” character. At least I think it’s the same character as the man in that panel where she calls him “Daddy” (that’s the scene Chris was talking about as being so poignant.) Chris thinks he’s the character in the grave at the beginning too, but I’m not sure. I mean, do the zombies re-grow their skin? I think I don’t know enough about zombies…

I really don’t want to go into details but as a whole it seemed very predictable, lacking in any degree of suspense, uninvolving on an emotional level (the damp squib of a “romance”) and somewhat pat in its denouement (the burning of the house to assuage the undead). I suppose the final page has a sort of Watchmen like sting to it (still slaves and still in dead end jobs). It was a chore to get through and told me nothing new about the headline issues. I think Moore bit off more than he could chew in the course of these 2 short issues.

The pleasures that can be derived from #41/42 are entirely in the details (some of the narration, the voodoo mastheads, portrayal of the zombies etc.). It’s pretty tiresome as a whole. I’m not saying you can’t make some hay of the various elements in these two issues (as people used to do with The Dark Knight Returns in some academic journals in the past) but on an aesthetic level these comics are mediocre.

From the conversation above, you seem to have read/treated Swamp Thing mainly as a diversion and not something worthy of serious consideration as a good/great comic.

I think Suat’s right about the Zombie issues. They’re pretty trite/offensive on the race relations level and nothing about the plot/story/art/combination redeemed them for me. The idea of the zombie/ghostlike past of the U.S. south coming back to haunt it is hardly original–It’s pretty common to contemporary fiction–and this is far from the best example of those tropes. I tend to think the infrequency of Moore’s actual experience with the U.S. (and esp. the South) doesn’t help him when tackling concrete historical issues like slavery. I think that these issues are really among the worst of the run, esp. coming right on the heels of the werewolf.

What’s the press that’s publishing this collection on Southern comics?

Hi Suat and Eric: I absolutely agree that overall the issues fail and they didn’t hold my attention easily either.

I did like the first and last pages a lot, though, and I think they give hints at what it might have been like if he’d managed to chew it. I didn’t pay much attention to the “ghost of the past coming back to haunt” trope because those story elements were just so colossally tedious that I skimmed over them entirely.

This issue makes me think of unfinished stories you find in author’s papers, except that because it’s commercial, it got released. You’ll read and there’ll be a handful of wonderful phrases, just enough to recognize the author’s voice, and the germ of a great metaphor or storyline, but overall it’s just a mess. But — as we pointed out in the Chris Ware thing — there’s something appealing about a mess. It is, however, more appealing in the thinking-about than in the reading-of.

I did read it mostly as a diversion — not terribly self-consciously but just because I wanted give it a fair first-time reading without the overburden of literary reading — which is why I was so pleasantly surprised to find jumping out at me the skeleton of the thing I always look for as my first measure of literary art: thematic consistency on all levels, both intra- and extra-diegetic, in this case the “fecundity.”

(We couldn’t come up with a title we liked, and the next day, after I posted, we decided we should have called it “Swamp Thing is Fecund Awesome.”)

I don’t think that Swamp Thing’s “fecund consistency” makes it a “great” comic, but I do think that any comic that does NOT have that kind of thematic consistency probably won’t be one I consider great. It’s necessary, but not sufficient.

I think it’s University of Mississippi, Eric. Google Qiana and “US Comics” and it comes up.