When two specks in the distance start shooting at Ferdinand Bardamu on the first page of Céline’s Journey to the End of the Night, he quickly comes to the unshakable conclusion that it is all a big mistake. His only viable option is to get out of that situation as soon as possible. The colonel overseeing his fate, a man with no use for fear, is deemed a “monster” and “worse than a dog”, but absolutely typical of the army as a whole:

“…I realized that there must be plenty of brave men like him in our army, and just as many no doubt in the army facing us. How many, I wondered. One or two million, say several million in all? The thought turned my fear to panic. With such people this infernal lunacy could go on forever….Why would they stop? Never had the world seemed so implacably doomed.”

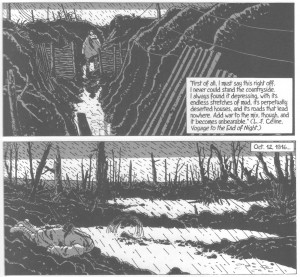

Bardamu’s attitude is one of absolute revulsion for his commanding officers. The report that his sergeant has been blown up while going to meet a bread wagon is an occasion for celebration (“that makes one less stinker in the regiment!…In that respect you can’t deny it, the war seemed to serve a purpose now and then!”). The countryside? Even on the best of days “dreary” and godforsaken, “if to all that you add a war, it’s completely unbearable.”

If a reader wants to understand the driving force behind Jacques Tardi’s It was the War of the Trenches, that person need look no further than Céline and his famous novel. Here bravery is seen as the enemy of logic. The heroes of Tardi’s comic are hate, fear and cowardice, the only sensible reactions to being asked to perform the impossible under insane conditions. This is not a wholly truthful or complete picture of the Great War and it is one which is unlikely to be recognized as such by any surviving veterans. So much the better as far as Tardi is concerned:

“This is not the history of the first World War told in comics form, but a non-chronological sequence of situations, lived by men who have been jerked around and dragged through the mud, clearly unhappy to find themselves in this place, whose only wish is to stay alive for just one more hour…”

“It was not my goal to create a catalogue of weapons and uniforms…I avoided any and all “historical” events that have long ago been analyzed and filed away by historians, or better yet, related by witnesses…The only thing that interests me is man and his suffering, and it fills me with rage.”

There are no great deeds in Tardi’s comic. No Légion d’honneurs, no Croix de guerres, no Victoria or Iron Crosses. No suggestion that only the brave and courageous have the right to cry out in protest. No sense of fellowship, no pitched battles to gratify our base senses and desires, and certainly nothing of that most typical of war time sensations, boredom. There is certainly truth in most of these presentations of war, all ably presented by those who seek to find meaning in adversity (a very human predilection), those who seek to honor the fallen, those who seek to relate personal truth and, yes, even those whose jobs are to fill the ranks of our modern armies for reasons of national defense. But Tardi’s purpose is not commemoration or exaltation but to elucidate what he feels is the most important and “banal” lesson of this and any war: the absolute horror of it. Or to be more precise:

“What retained my attention is the man – whatever his color or his nationality – who is considered disposable, whose life is worth nothing in his master’s hands..a banal observation that remains valid to this day.”

The purpose of this is indeterminate. Is it so we should not too willingly enter into such ventures or as Count Otto von Bismarck once said in a speech to the Reichstag in 1867:

“Anyone who has ever looked into the glazed eyes of a soldier dying on the battlefield will think hard before starting a war.”

Is it an antidote to the means and “phrases” used in recruitment and channeled through society with techniques both obvious and subtle (and the gradual washing down of our resistance to the same)? Perhaps, these are the most obvious and mundane answers. It is sufficient to note that Tardi’s polemic is firmly anti-war though not strictly pacifist.

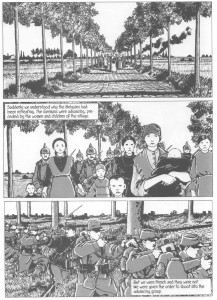

[See commentary on use of living shields from Belgium in War Time]

All of this seems to be conveyed with the cynical understanding that those who remember the past are condemned to repeat it anyway. The force of intent, the relentless focus on everything that is hateful about war over shadow the intermittently dry and clumsy narration, the sometimes innocuous expressionistic terror (something which does not come as easily to Tardi as it does to, say, Alberto Breccia for example) and the overly familiar tales (such as the use of Decimation as a form of punishment for cowardice).

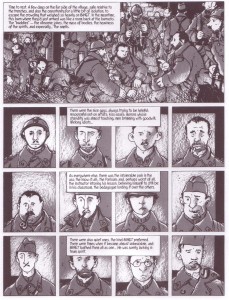

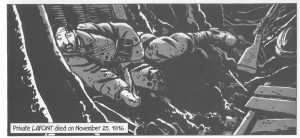

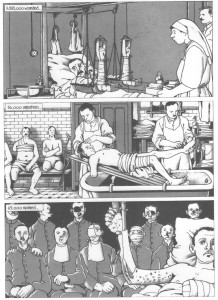

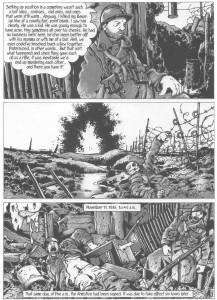

The soldiers who populate Tardi’s story are umbral figures who elbow past us in this subterranean inferno; ciphers and strangers with unknown histories, known to us only by rumor and anecdote before they meet their ends within a few terse pages. They have names but we can barely remember them. There are only the images: the man with his guts in his hands; the soldier with his half his face annulled by shrapnel; the nameless penitents who line the amputee’s sanatorium; the grands mutiles provided with “secluded rural settlements…where they [can] holiday together.” (The First World War, John Keegan)

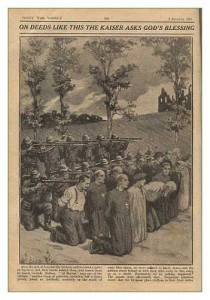

The effect of this curt catalog of pain is not individual remembrance and is the opposite of the propaganda which once emanated from pens and brushes of Allied writers and artists during the war; that which led the British war artist, Paul Nash, to famously remark that,

“I am not allowed to put dead men into my pictures because apparently they don’t exist.”

But it is a kind of propaganda nonetheless, and it finds expression and feeling in one of Nash’s letter from Passchendaele:

“I have seen the most frightful nightmare of a country more conceived by Dante or Poe than by nature, unspeakable, utterly indescribable. We all have a vague notion of the terrors of a battle, and can conjure up with the aid of some of the more inspired war correspondents and the pictures in the Daily Mirror some vision of a battlefield; but no pen or drawing can convey this country…Evil and the incarnate fiend alone can be master of this war, and no glimmer of God’s hand is seen anywhere. Sunset and sunrise are blasphemous, they are mockeries to man…The rain drives on, the stinking mud becomes more evilly yellow, the shell holes fill up with green-white water, the roads and tracks are covered in inches of slime, the black dying trees ooze and sweat and the shells never cease…It is unspeakable, godless, hopeless. I am no longer an artist, interested and curious. I am a messenger who will bring back word from the men who are fighting to those who want the war to go on for ever. Feeble, inarticulate, will be my message, but it will have a bitter truth, and may it burn their lousy souls.”

The object here is not to elicit pity but to portray the unrelenting dehumanization and madness of armed conflict. It is, of course, not a first hand account though some of these memoirs are mentioned favorably by Tardi in his introduction (Ernst Jünger’s Storm of Steel for instance). The other difference between these books and Tardi’s comic is apparent but seldom highlighted – they were frequently written from the viewpoint of officers. Two of the most celebrated accounts of the Great War are written from this perspective, the aforementioned account by Jünger and Robert Graves’ Good-bye to All That.

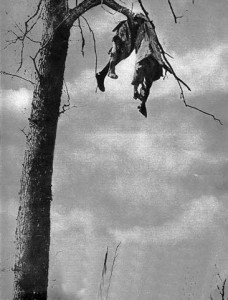

The horrors are ever present in Jünger’s memoir: a leg hangs loosely from a tattered body; an artery is struck and packets of lint exhausted soaking up the mess as the man bleeds to death; the dead are sprawled across no man’s land in various stages of decay, the corpses left to rot unburied, in eternal rest yet in visual and olfactory communion with the living. There is little time for lengthy contemplation as one might expect from a work derived from a war time diary. Instead what we get are straight descriptions of foreboding and fear. The war – its horror, its excitement – moves ever forward. The tension here is not between good and evil or even war and peace (though this occasionally rears its head) but between simple adventure and patriotic sacrifice – a terrible portrait of resignation, accommodation and the acceptance of murderous intent:

“We were up for it, in the best and most cheerful condition, and expressions like ‘avoid contact with the enemy’ were not in our vocabulary. Anyone seeing the men round this jolly table would have to tell themselves that positions entrusted to them would only be lost when the last defender had fallen. And that indeed proved to be the case.”

And later of a steel helmeted infantry man…

“Nothing was left in this voice but equanimity, apathy; fire had burned everything else out of it. It’s men like that that you need for fighting.”

It is very far from the ideas surrounding anti-war fiction and the reader will find it quite easy to understand why the novel was embraced by the Third Reich. The whispered shout above the morass of detail is not “beware”, “avoid” but we sacrificed, we overcame, we looked into the abyss and became men.

Written several years after the close of the war, Graves’ memoir is a different kettle of fish. In the biographical essay which accompanies the Berghahn Books edition of Good-bye to All That, Richard Perceval Graves writes (quoting Grave’s essay “P.S. to Good-bye to All That”):

“From the first Graves intended the Good-bye to All That should be a popular success; and later wrote that he had: ‘more or less deliberately mixed in all the ingredients that I know are mixed in other popular books…murder…mothers…T.E. Lawrence…the Prince of Wales…But the best of all is battles, and I had been in two quite good ones…So it was easy to write a book that would interest everybody.'”

Paul Fussell adds a further twist to this in his reading of Graves’ book in The Great War and Modern Memory:

“Of all memoirs of the war, the “stagiest” is Robert Graves’ Good-bye to All That…working up his memories into a mode of theater, Graves eschewed tragedy and melodrama in favor of farce and comedy…And what is a Graves? A Graves is a tongue-in-cheek neurasthenic farceur whose material is ‘facts’….His enemies are always the same: solemnity, certainty, complacency, pomposity, cruelty. And it was the Great War that brought them to his attention…If it really were a documentary transcription of the actual, it would be worth very little, and would surely not be, as it is, infinitely re-readable. It is valuable just because it is not true in that way. “

Graves’ was scarred by his war time experiences, yet much of his memoir suggests a man who still wants to keep up appearances. There is everywhere the feeling of camaraderie, a sense of duty tinged with irony and admiration. There is a certain pride taken in the proper running of the infantry battalions as well as the discipline required thereof; an interest in the proper conduct of trench warfare, the niceties of military drills, the maintenance of boundaries between officers and enlisted men and the perfection of communal action in combat.

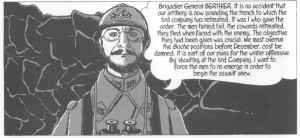

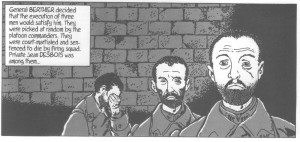

[Two facing images from Tardi’s comic]

Tardi will have nothing to do with this. The soldiers of It Was the War of the Trenches are the laggards and liabilities so despised by Graves and Jünger. They are unpatriotic, poorly trained, lacking in initiative, misanthropic, cowardly and completely lacking in esprit de corps. They are in every sense bad soldiers and in almost every instance dead soldiers.

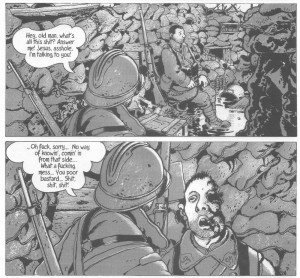

Such is the case with Binet, the bloated corpse we see at the start of Tardi’s comic, mocking and hateful in all his ruminations.

The portraits of his trench mates are lined up like the half-remembered prisoners of a death camp: the put-on artists, the kiss-asses, the morons – Binet “loathes them all”. It is the only way he knows how to survive. And it is because Binet cannot forget that he finally dies, rushing into no man’s land in search of the long forgotten corpse of a “friend”.

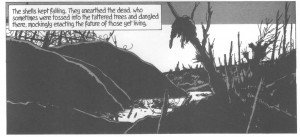

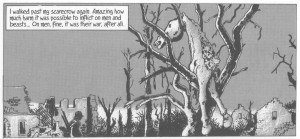

Tardi’s tale is crammed with these obliterated figures: carcasses tossed into trees at the behest of artillery shells…

…an infantry man destroyed by shrapnel even as he remembers his fear when faced with the order for mobilization…

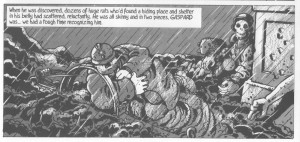

…the black market trader caught in a bear trap whose body becomes a shelter for rodents…

…mad men, cowards, murderers, thieves; all of them anonymous, all of them looked upon with disapproval in times of war, all of them remembered in this book because of what war has made of them; an echo of Ferdinand’s conversation with Lola in Céline’s novel:

“But it’s not possible to reject the war, Ferdinand! Only crazy people and cowards reject the war when their country is in danger…”

“If that’s the case, hurrah for crazy people! Look, Lola, do you remember a single name, for instance, of any of the soldiers killed in the Hundred Years War?…Did you ever try to find out who any of them were?…As far as you’re concerned they’re as anonymous, as indifferent, as the last atom of that paperweight…Get it into your head, Lola, that they died for nothing! For absolutely nothing, the idiots!”

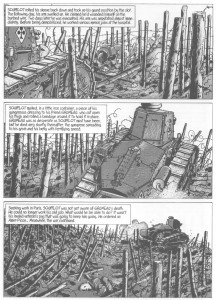

Tardi’s story has “idiots” to spare. One of the more effective vignettes occurs over two pages where a solider introduces a filthy needle into his arm in order to escape the front via a suppurative wound; here juxtaposed with images of a Renault FT-17 ploughing relentlessly through fragile defenses, leaving crumpled and masticated bodies in its wake.

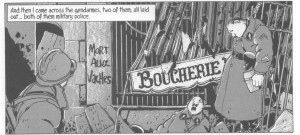

Tardi offers a modest amount of this kind of artistic reinforcement throughout. The French tricolore is brought up for ridicule in the placement of these atrocities within the confines of three uniform rectangular panels per page (Art Spiegelman sees a relentless beat in this repetition; Sean T Collins identifies them as “miniature trenches”). The litany is taken up by the recurrent imagery. Men are strung up like scarecrows, some hanging from trees, others draped on barbed wire like flaccid dolls. Corpulent military policemen are dangled like fresh meat outside a butcher shop by the sheep they were suppose to guard; …

…a barely recognizable horse – a disemboweled half-human thing – is seen peering curiously from a tree.

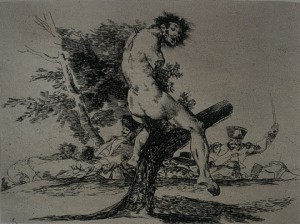

[The Disasters of War No. 37 “This is Worse”]

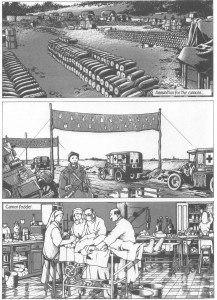

But there is little time for such meditations on these Stygian fields. Time and death wait for no man. The artillery shells are laid out in neat rows awaiting direction, the hospital theater is a strangely sterile and unmuddy trench, the zombies laid out for inspection.

One solider is worried about lice, another about digging a trench in a cemetery. Now nameless and dead on the day of armistice.

Related Material

(1) Preview, blurbs and publishing history of It Was the War of the Trenches

(2) Kim Thompson on translating Tardi

(3) Tardi’s illustrations for Louis-Ferdinand Céline’s Journey to the End of the Night

(4) Sean T. Collins on Tardis’ art, a review of Tardi’s comic at Joes’ Reviews, a review by Dan Nadel and Kristian Williams’ take on the book

Tardi’s comic is a complex work which can be approached in a number of ways. I’ve simply chosen the most obvious one in this instance.

There is of course the question of whether Tardi’s comic brings anything new to the table with regards the Great War. We should first dispense with the idea that the work is notable simply for being executed in the form of comics. Such a notion might be acceptable for people who have a particular investment in comics but is of little use to vast majority of readers.

Having said this, there are elements inherent to comics which do enhance the experience of reading Tardi’s book. Some of the reviews above address Tardi’s comic from this viewpoint. The short episodes that comprise It was the War of the Trenches work quite well when thrown together to form this impassioned collage of black ink. The lack of overt markers signaling the end of one story and the start of another allow these tales and characters to meld into one another in a way which I suspect would not have been as satisfying if filmed or as visceral if conveyed in prose. Much popular fiction relating to the Great War (actually war in general) has an overriding narrative enforced over the proceedings. Tardi eschews this and what we are presented with seems closer to the experience of viewing a series of paintings or photographs elaborated upon for context and emotional resonance. This abbreviated, staccato-like approach is something which grew out of the album’s serialized roots. The reader dictated pace at which these static, forceful and occasionally multi-layered images unfold adds to the comic’s power; that ability to set aside, reread and to dwell inherent in narratives transmitted in the form of physical “books” accentuates our experience of these war time accounts.

Some might say that the Tardi’s comic has limitations in terms of its conceptual strength but I often find that an overzealous sheen of “artistry” hampers truth when it comes to the subject of war. That act of elevating some formal aspect or literary quality often has the effect of diluting and obscuring the essential truth of conflict. Tardi provides just enough of this to keep us engaged but his focus on a very particular and one-sided truth is steady and unrelenting; that “truth” being that war is unmitigated suffering and devoid of value. I imagine that such an unnuanced view of war isn’t the whole of Tardi’s conception of it but it is the undeniable thrust of this comic. It is an unusual artistic object in that sense, especially if one considers the vast majority of depictions of war in film and comics where there is often some light or redemption.

A quick note on one of these reviews. The writer at Joe’s Reviews suggests that Abel Gances’ J’accuse was “obviously an influence on Tardi”. I have no firm knowledge of this and perhaps the reviewer cites Gance’s film only for its imagery (especially in its third act). But lest there be any confusion, let me just say that Gance’s film is considerably more romantic and theatrical than Tardi’s comic. It is truly a product of its time filled with a surplus of strained caricatures, varied acts of heroism and camaraderie, awkward anti-German propaganda and a profusion of gothic and poetic elements. The almost ridiculous chivalry and melodrama found in this important and seminal film seems to me to be the very anti-thesis of Tardi’s comic.

You don’t quite say this, but it seems like at the end you’re flirting with an argument that comics’ lack of sophistication is in this case perhaps more effective, in that more satisfying aesthetic treatments of war end up being morally (and therefore aesthetically) compromised in various ways. Would you agree with that, or is that not really where you were headed with this?

Suat:

Have you seen Tardi’s great _Le trou d’obus_? It’s the first part of _C’était…_, but larger and in glorious full color.

Hi Domingos. I haven’t seen Le trou d’obus. Does it improve the comic? I actually think the first section of It was the War of the Trenches is also the weakest part of the album as a whole, and I sort of understand why Drawn and Quarterly chose to start with the latter sections of the book back in the 90s when they attempted to serialize it.

Noah: Not exactly. I don’t think it’s possible to accuse Tardi of a lack of sophistication in It was the War of the Trenches. But I do think the tension between “truth” and that which is “sophisticated” or aesthetically pleasing is especially problematic when it comes to stories about war. Take Fussell’s approach to war literature and his admiration for Graves’ book for example. I have no quarrels with the idea that The Great War and Modern

HistoryMemory is an impressive work of scholarship and erudition but his complaints about certain types of war literature (he dismisses Storm of Steel in a few sentences for example) seems to derive more from personal taste and temperament as well as his huge consumption of material related to the war, much of which is solemn and straightforward in its methodology.My feeling is that comedy and farce (the theatrical) is not an inherently superior approach or even the most successful way in which the reality of war can be conveyed to a reader who might read only a handful of books on war in his lifetime. Comedy helps us to resist lies by turning objects of respect into objects of ridicule but it also often turns the war into a kind of entertainment which relieves us of the memory of the pain and misery which we are discussing. So while I can envision a day when we will see a musical farce about the Holocaust (there may be one out there already) I do not think that it will be the best, most enlightening or most truthful means by which we will approach the subject. It will be an alternative to tickle our jaded minds.

In much the same way, I find that Good-bye to All That often reads like an entertainment; an enjoyable, amiable and aesthetically pleasing ramble about misery. As with Catch-22, there is undoubtedly truth in Grave’s mild parody of war in which see the military as an absurd bureaucratic institution, yet Graves often buys into the whole system in ways which I mention above (his stiff upper lip and adherence to the values of his position). Herein lies the tension. These are values which are required in the proper conduct of war (and thus for survival in those times). They are also the values which allow leaders and governments to push their populations willingly into such adventures. The positive effect of Tardi’s position in It was the War of the Trenches lies in his refusal to see any value in war; he rejects everything which might soften our wills and allow us to accept its necessity. His abilities as an artist and his formal skills (his ability to “entertain”) are never at the forefront – it’s content front and center..

I’m not saying that it is impossible to create a work in which the complex truths about war sit comfortably with an overwhelming aesthetic sense but these are rare. I don’t feel that Graves’ memoir is an example of this and, since Domingos just commented, I would say that his favored Alex Toth story (White Devil, Yellow Devil) fares even worse if viewed in this respect. Tardi’s comic isn’t an example of that rare work of art as well, but most readers won’t come away from it with an overwhelming desire to praise its superlative aesthetics over its raw emotion and grasp of the most important truth about war. I think it’s a worthwhile book in that sense.

It’s “The Great War and Modern Memory,” just fyi.

I think that’s an interesting take, though I’m not sure I’m wholly convinced. I think the critique of Graves seems apt (though I think Heller does something rather different) but I wonder if you can really break this down into a content/form argument. As you note in your review, people do, and have, appreciated Tardi’s formal approach to the topic (layering panels, for example.) Even you do this, since the decision to emphasize certain aspects of the war (in this case, its evilness) is a formal choice as much as a choice of content.

And is Tardi’s approach *really* the most effective anti-war stance? Doesn’t his didacticism make his argument easy to dismiss and/or parody?

In the end, it seems like you’re arguing that an earnest, non-humourous, straightforward approach to these issues is by its nature more effective in conveying the horror of war. I’d say that, while it is worthwhile to remember that humor is not in and of itself effective (or for that matter funny) rejecting it a priori as a rhetorical tactic seems shortsighted. I’d agree that humor isn’t going to end war — but then, straightforward jeremiads aren’t either. Tardi’s book hasn’t stopped war, that I’ve noticed.

I guess the point is that “raw emotion” and “grasp of the important truth about war” are *aesthetic achievements.* Somebody praising those is praising the book’s aesthetics. It’s a difference between one kind of aesthetic experience and another, not between aesthetics vs. non-aesthetics that you’re discussing.

Which isn’t to say that Tardi’s book is bad. I haven’t read it, but the panels here seem interesting, and I’m certainly open to the suggestion that it’s better than Grave’s memoir (which I read a long time ago, and might well like less now.)

Oops, I’ve corrected the title of Fussell’s book in the comment above.

Someone with a better grasp of the influence of anti-war literature on the conduct of war would be better equipped to answer some of the questions you raise. Tardi’s book isn’t going to stop war in the same way that *nothing* is going to stop war (in general). War will be with the human race long after we’re both dead. For all I know, it may even be an inextricable part of our nature.

But my feeling is that if the overwhelming perception of war in the media was from Tardi’s perspective, we might see much less support for it. As is, the overwhelming effect of the media coverage (in both fiction and non-fiction) is to advocate the beneficial effects of war (of which there are many). And if you’ll read the third paragraph of my first comment again, I don’t reject humor “a priori as a rhetorical tactic”. As I imply, I think it’s very useful in that sense. I was referring to truth as an end in itself rather than truth as a purely “utilitarian” concept (but this is a philosophically difficult area).

I don’t know if the “raw emotion” of Tardi’s comics is an “achievement” but it’s certainly an aesthetic choice. Perhaps the choice of the word “aesthetic” was imprecise since you might say that everything in a work of art is some form of “aesthetic achievement”. What I meant (more precisely) was the feeling of being in the presence of something “beautiful” and pleasing to our senses which naturally leads us to investigate primarily *how* it was achieved rather than dwell on its final effect. The division between form/content (which has been discussed at length on HU) is always going to problematic but I think it’s possible to differentiate between the two on a more elementary level which is what I’m doing here.

Suat:

From your point of view _Le trou d’obus_ is even worse in glorious color (he he) and huge size than the b & w reduced beginning of _It Was the War of the Trenches_. I think that Noah is right: art aestheticizes, it’s unavoidable. The truth is that war is, as someone put it, quite photogenic (or, in this case, if the artist has any talent at all, beautifully drawable). It’s the same thing with the depiction of poverty. The artist may be a bleeding heart full of good intentions and yet, there will always be an hint of aestheticism and, even worse, exploitation.

It’s a very difficult problem and I don’t have any solutions. Looking at my favorite books about war I find no answers because I find them… expressionistic, yes, and gothic, or something, but also very beautiful: http://tinyurl.com/2v7k2ck http://tinyurl.com/39uv3ku

As I said in my second stumbling my favorite war stories are Oesterheld’s. He explicitly said that the true enemy aren’t the soldiers on the other side of the barricade. The true enemy is war. Not because it kills and maims, but because it destroys our decency. Here’s how he put it: “In all wars, and also in all peace, every soldier, every man, fights his own fights. Those who win are few, very few. Soldier Antón Kirchenheimer, of Saxony, was one of those few.” He won because he sacrificed himself maintaining his humanity in spite of all the brutality and horror.

This is humanistic and romantic and, if we want to be cynical, even tinged with sentimentality. I like it a lot in spite of all that though…

Lots of interesting thoughts here, though right now I just wanted to point to one thing: Tardi far from eschews humor. Pretty much all his comics are darkly humorous, and War of the Trenches is not exception, although he keeps it more sober than some of his other work. But who can ignore the ridiculous, but also resonant, leitmotif of each soldier screaming for his mother before he dies?

The lack of overt markers signaling the end of one story and the start of another allow these tales and characters to meld into one another in a way which I suspect would not have been as satisfying if filmed or as visceral if conveyed in prose.

Quite correct as far as film goes. A perfect example would be one of the films listed in the “filmography” page in the back of the book: Georg Wilhelm Pabst’s Westfront 1918(1930). The film has some of the dissonance of the Tardi book with a similiar treatment of most of the main characters. Though it still pales in comparison, even while lacking a conventional structure. Here’s a clip. Note that it’s the last ten minutes of the film.

The writer at Joe’s Reviews suggests that Abel Gances’ J’accuse was “obviously an influence on Tardi”. I have no firm knowledge of this and perhaps the reviewer cites Gance’s film only for its imagery (especially in its third act).

The aforementioned “filmography” page in the back of the book does list “J’Accuse” among its three dozen WWI-related titles. And on the following page, there is a bibliography listing about forty titles. I was going to assume that these were Tardi’s references, but the works listed reach up to 1994, which is of course one year after the book came out. Maybe these are the publisher’s “recommended reading” list? If so, they unfortunately left out Wilfred Owen.

Thanks for the link to the Pabst film. I haven’t seen it. Is that your article you linked to at Senses of Cinema? I’m assuming that “siegfriedsasso” is an online moniker. If it’s not, my apologies. Anyway, I see that Robert Keser (the writer of the article on Westfront 1918) comes to the same flawed (according to Noah and Domingos) point as myself:

From reading that review, it does seem like a close cousin of It was the War of the Trenches though Tardi seems to give even less time for us to concentrate and identify with the figures in his comic. I think that’s one reason why the comic seems so unsentimental.

As for the bibliography at the end of the album, I think they could still be Tardi’s references since Kim Thompson was in correspondence with Tardi during the translation of the book. I think if you took some stills from “J’Accuse” they might look a bit like the comic but the overall effect definitely tends towards the melodramatic.

I’m not a professional writer; yes, this is a just a monicker.

Pabst does the best he can to “deromanticize” the subject matter, as Keser put it. Nevertheless, like with the point Domingos made, aestheticism does rear its head to a certain degree. The battle scenes are impressively put together. It’s fairly exciting to watch. This is certainly a problem that the Tardi book doesn’t have. What’s more, Pabst is working in more of a minor key. His stance is appropriately anti-war, yet in the end one feels there’s something missing. He’s nowhere near as vehement or as wide ranging in his social commentary as Tardi. He doesn’t bite hard enough. And while there are a good number of grisly deaths, they’re not as vividly horrific as the book’s. It speaks yet again to the limitations of film. To get that balance right in depicting real life horror without aestheticizing it must be extremely hard to pull off.

The reader dictated pace at which these static, forceful and occasionally multi-layered images unfold adds to the comic’s power; that ability to set aside, reread and to dwell inherent in narratives transmitted in the form of physical “books” accentuates our experience of these war time accounts.

Yes, and this is the completely opposite experience of the Pabst film, which is one reason is doesn’t resonate as much as the book does.

I think if you took some stills from “J’Accuse” they might look a bit like the comic but the overall effect definitely tends towards the melodramatic.

It wouldn’t take much for two different works depicting trench warfare to have at least a few things in common. Most of them are going to have barbed wire, rats, mustard gas, etc. Definetly a superficial comparison from that “Joe’s Review” writer.

What do folks think about something like The Naked and the Dead? It’s obviously very aesthetic — shifting points of view, flashbacks, very accomplished writing. The view of warfare it puts forward is pretty bleak though; the men basically all hate each other, the outcome of events is presented as being entirely random, heroism comes across as a character flaw, the general is a fascist asshole, etc.

I don’t know that I even like the book that much, but I don’t think the problem with it is that is pays attention to aesthetic concerns and therefore doesn’t portray the war as sufficiently miserable.

I guess I’m again resisting the idea that the issue in war representation is slickness/amateurness, or a kind of aesthetic competence vs. a disavowal of that competence. I mean, yes, formal presentation is related to ideological content, but it seems like *how* those two relate would be an individual question.

Suat, what do you think of that Rosenberg poem Fussell discusses with such enthusiasm? I remember really liking it, but I read that a long time ago…. You probably find it too distanced and elegaic, yes?

Siegfriedsasso: Yes, even from that small clip on Youtube I could see that the battle scenes were quite impressive in their construction. And it’s true that Tardi’s comic is almost devoid of any “excitement” which might be associated with depictions of this. It’s one of the least exciting war comics out there.

Noah: It’s been far too long since I read The Naked and the Dead to give a fair commentary on it. I have only impressions. Your initial comments all seem to be accurate. The divide between beauty and misery/ugliness is something which is applicable to Tardi’s comic but there may be other reasons why you didn’t like Mailer’s book. Was it perhaps too “literary”, that species of muscular American literature which you despise?

It’s not slickness vs amateurishness we’re talking about here since both Pabst and Tardi aren’t even remotely close to being amateurish. Both are masters of their respective forms. It’s a question of whether the artist wants to be subservient to the material or place the needs of entertainment first (is this a moral dilemma, an aesthetic decision or just an uncolored personal decision?). So at the most basic level, it’s simply a question of which aspect of the work you notice immediately – its content or its artistry. Since war isn’t a beautiful experience (this is a generalization of course, it’s obviously delightful to a number of people), I just don’t think our *primary* experience of a work related to it should be that of lyricism and pleasure. However there are obviously many aspects of war which can be aestheticized, its surreal or terrifying atmosphere for example.

As a former military person who been directly involved in war and suffered as a result of it, Fussell’s demands as a writer and reader are different from my own. He doesn’t need a direct account of war since this is something which he’s intimately acquainted with both through personal experience and literature. For a person who has the intellectual and psychological abilities to filter and assimilate first hand experience, an artistic object may pale in comparison to the “real” thing, hence his disdain for more direct and insufficiently aestheticized transcription. As for Fussell’s description of the Isaac Rosenberg poem (“Break of Day in the Trenches”), I can’t go into specifics since I am at work and don’t have the book in front of me. There’s little doubt that it’s a beautiful poem and on reading it I’m immediately struck by its language, imagery and metaphors, and then its resignation and irony (though these emotions will lose context with the passage of years). And perhaps that’s the direction from which Fussell is approaching the entire matter – that poetry and literature should be primarily assessed for its aesthetic beauty, in the way we might we read The Iliad as some beautiful remnant of ancient wars. Maybe what will count in centuries to come will be this aesthetic approach and not the hard kernel of truth and reality which can be better obtained through written history and first hand accounts.

I don’t know that it’s the literariness I don’t like in Naked and the Dead…though maybe…? I found the internal monologues, flashbacks, fairly stereotypical and not especially insightful. Similarly many of the characters didn’t ring true to me, especially the general; he seemed too easy as a villain. The obsession with/distaste for women was not especially appealing.

I think Fussell would probably argue that irony is the way to get at the reality of war — that the looking for an authentic, unironized core (in history or literature or anywhere) is mystification. That is, for him, irony (a literary trope) is central to the true lived experience of war. That is, aesthetics are important not because they are more beautiful, but because they are more true.

I think that’s where Tim O’Brien is coming from as well. And Tobias Wolff. And possibly Stephen Crane (though is the Red Badge of Courage anti-war? It’s probably the greatest English-language war novel, one way or the other.)

In any case, history is a literary genre, and so is memoir. You don’t get around the problem of aestheticizing war that way.

I think irony is the way certain combatants deal with the war especially if the actual experience is too terrible to relive through their writing. It’s the way conscripts and unwilling participants deal with the bureaucratic mechanisms of the military – sarcasm, self-pity, black humor – the civil service with death mixed in. It may also be that the actual experience of killing and death becomes far too banal and is rejected as an artistic approach.

Having said this, I have a reasonable amount of sympathy with Fussell’s point of view since a lot of the war-related art I appreciate is in fact quite aesthetically pleasing (as Domingos alludes to above). I just tend to have reservations when my primary experience (as with the Rosenberg poem) is from that view point. Btw, I thought you were hesitant about privileging the soldier’s point of view above all else? Why are all the authors you name (except for Crane) people with actual battle experience? A considerable amount of the Chinese literature relating to war is actually from the viewpoint of civilians (some of it by people with no direct experience of it). Some of it is indeed beautifully written but if there’s one thing the mainland Chinese authors have down pat is their ability to convey absolute misery. I think lived experience must have something to do with this.

You’re right in your points about history and memoir but historical writing can afford to be less theatrical and lyrical in a way poetry and fiction can’t. Also, I was talking about letters and diary entries which are often not designed for publication or a wider readership. So it doesn’t get around the problem entirely but the problems are less pronounced.

I don’t think Wolff had actual battle experience…? His memoir is mostly about sitting around base, if I remember right. And I did say Crane’s was the best one!

The thing is, misery and horror can be their own consumable aesthetic, can’t they?

Wolff: That’s not my memory of the book. Doesn’t he come under fire while working as a military advisor? Oh well, yet another book for the reread pile I guess.

And I agree with you when you say that “misery and horror” can become a “consumable aesthetic”. The opening segment of Saving Private Ryan is a classic case of this. You know something has gone very wrong when people start citing that segment as a perfect test for your audiophile equipment. And the entire, sickening Cultural Revolution publishing circus is another example. The absolute worst culprits in this case are the Chinese dissidents who migrated to the West. If you want to read some of the most overrated Chinese writers, just read guys who get published and honored in the U.S., guys like Ha Jin who won a National Book Award.

Huh. That’s interesting, Suat. Russian and Czech emigré dissident writers were of a very high calibre. I wonder why the Chinese didn’t measure up?

For one, they’re not writing in their native language. Secondly, there’s little doubt in my mind that the awards are politically motivated (and this reflects who gets published) – a terrible way to judge art. Thirdly, the unusual settings of these books (not your usual Western environments) may lead reviewers and juries to make flawed judgments based on novelty and not literary merit.

Having said this, I have to say that something like Gao Xingjian’s Soul Mountain actually isn’t too bad (I wouldn’t read the books that followed that one). He wrote the novel in Chinese and lives in France though. And, he’s definitely not as skillful or versatile as someone like Mo Yan (who remains in China).

Which Russian and Czech dissidents are you talking about?

Solzhenitsyn, Kundera…Granted, Solzhenitsyn got pretty indigestible in his old age.