During our ominously metastasizing roundtable on R. Crumb’s Genesis, one of the big questions that kept coming up was about whether you should compare comics to other things. Is it fair to set comics next to your meatloaf and say, “You know — comics. Not so tasty”? Is it okay to put them on the wall next to a crucified copy of Kierkegaard and then complain because your cloned angst-ridden philosopher is dripping blood all over a perfectly good Walt Kelly original, and you can’t appreciate the witty swamp patois because of the agonized ratiocinating?

In any case, I was thinking about these issues (more or less) while reading this piece by Matt Seneca. The post focuses on a single panel from Green Lantern #171, drawn by Alex Toth.

Cartooning is a white-knuckle walk down a tightrope with no end. The point of departure is illustrative drawing — the presentation of images from life, as observed in life. Plenty of artists never make it out of that realm, and as far as comics go there’s no reason why that has to be a problem. From Hal Foster to Jim Steranko, this medium has seen some fine realist artwork. But the realists ignore a fundamental challenge of the comics form: the creation of true picture-writing. Making the visuals simple and iconic enough that they carry instant meaning for the reader, with no contemplation required and no illustrative details slowing down the story. This hieroglyphic ideal is one of the more frequently stated goals of comics, I’d imagine because it separates the form from its two closest cousins, prose and illustration. Pictures that tell stories without words put comics outside the realm of the literary; and images used to inform rather than immerse fall beyond the illustrative.

But for all the hypothetical advantages of this “ideal” mode of comics, there’s an aspect of the medium it fails to consider: the sheer beauty of illustrative artwork. Charles Schulz and Jules Feiffer, to name the two artists who’ve perhaps gotten closest to a pure-iconographic realm of comics, read better, more smoothly, than pretty much any illustrative artist you care to name. However, I personally have always found something to be missing from the experience of their work as compared to that of Alex Toth, a devoted minimalist who nonetheless took pains to keep an inoculation level of illustrative information in his panels. All three of these artists searched relentlessly to strip excess pieces from their staging, excess lines from their rendering, excess detail from their shaping of forms. But where Feiffer typically dropped his backgrounds altogether, where Schulz indicated setting with sections of rigid fence post or bits of scrubby grass, and where both essentially drew everything with the same lineweight, Toth (along with the rest of his ilk, Mignola, Crane, Yokoyama) put just enough illustrative variation into devices like line and camera angles to give his version of iconographic minimalism the added verve of pretty pictures, of the visual world’s beauty.

Seneca goes on to argue that the split here between iconic/illustrative can be mapped onto that old standby, mind/body:

Schulz and Feiffer’s works (and those of R.O. Blechman and Ernie Bushmiller and, at times, Chris Ware) are comics of the mind, whether they be emotionally-based wanderings or dialectic ideas or even simple sight gags. But Toth drew action comics — comics of the body, of landscapes, of things that wouldn’t make sense if we couldn’t see them. This was his reason for shying away from the final pare-downs that the great strip cartoonists made: without the scraps of illustrative-comics grammar Toth employed, the environmental richness and kinetic cutting and hyperbolic figurework and variated lines, the material he drew simply wouldn’t have worked.

So, at first glance, you might say that this is an example of comparing comics to other things — specifically, the illustrative tradition.

The initial sentence, though, leads one to doubt. “Cartooning is a white-knuckle walk down a tightrope with no end.” That’s a statement of comics exceptionalism which, to me, doesn’t make a whole lot of sense unless you’re trying fairly hard not to think about other artforms. Cartooning is more white-knuckle than, say video art, which is poised between film on the one hand and the drop into television on the other? Or more of a tightrope than doom metal, poised between easy-listening fluff and the tectonic obliteration of your worthless soul? Or than performance art, poised between buckets of cow urine and tragic self parody? Any art involves difference — not that choice but this one, not this one but that one. That’s because communication and meaning are made out of difference. You might as well say asking for peas at the dinner table is a white knuckle walk, since you might slip and ask for corn or intimate sex acts instead. Indeed, Freud would actually say that (the bit about asking for peas being a white-knuckle ride, I mean, not the intimate sex acts. Though perhaps that as well, on second thought.)

Seneca then, is seeing comics as special. To do that, you need to don certain kinds of blinkers. In this case, those blinkers prevent Seneca from seeing illustration except in its relation to comics. Specifically, he argues that “The point of departure [for cartooning] is illustrative drawing — the presentation of images from life, as observed in life.” Illustration here, then, is realistic drawings meant to capture the look of life. This makes sense if you are talking about the pulp illustration that is important to the kinds of drawing Alex Toth does. It makes less sense, though, if you look at, say, this.

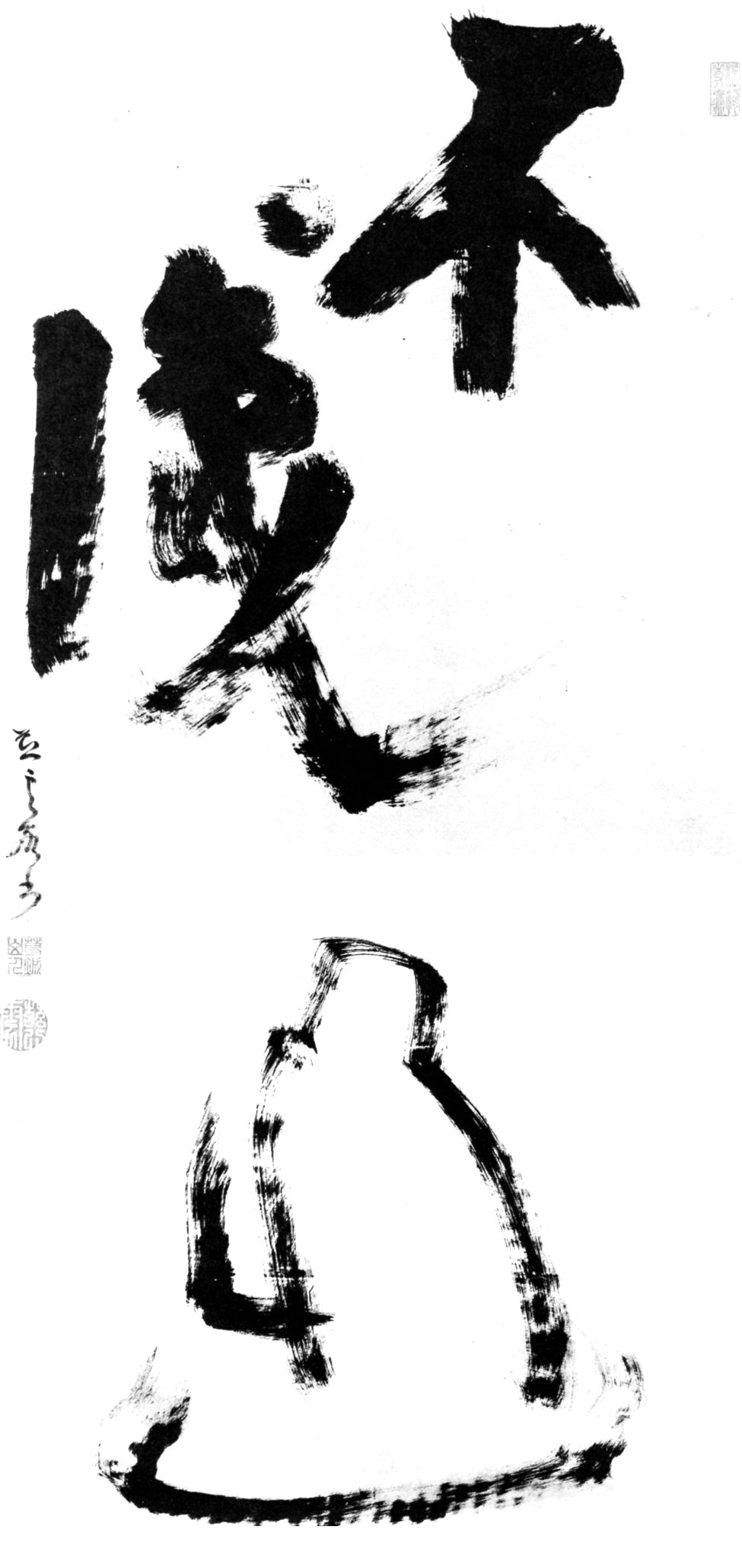

That’s an ink painting by Jiun Onko, an 18th century Buddhist priest. I wrote about it at length here. In this context, though, my point is simple…that’s an illustration.

Not only is it an illustration, but it’s a kind of illustration that is by no means marginal to the mainstream illustrative tradition. As you can see if you look at the below.

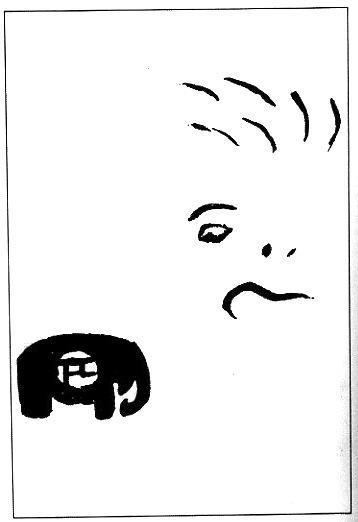

That’s Ooops! by Toulouse Lautrec, an artist who was consciously influenced by Japanese ink paintings…and whose drawings and posters, in turn, certainly seem to have been a forerunner of Toth’s style, even if they weren’t a direct influence.

So, if these are illustrations, then what does that do to the binaries Seneca has constructed?

First of all, it clearly calls into question the connection Seneca is making between illustration and realism. More than that, though, it upends the argument about the rationale for iconographic cartoons. Seneca is arguing that illustrative work is realistic and beautiful, but that cartoonists have to abandon that to make their pictures more readable. For Seneca, minimalism is chosen for ease of reading.

But if you look at the Jiun Onko and Toulouse-Lautrec drawings, it’s pretty clear that this is not a sufficient explanation. Jiun Onko, in particular, is more relentlessly iconographic than Schulz or Bushmiller; he provides less information. Indeed, he almost turns his image into a Japanese letter, or character. In that sense, his drawing is there to be “read” as Seneca suggests — but not in the interest of the sequential ease of information transmission. Rather, the image makes a connection between words, pictures, and reality — it’s an image which demands the reader/viewer/supplicant actively participate in constructing all three. Thus, the choice of an icon here is not utilitarian, but aesthetically meaningful. To draw iconically is not a default failure to incorporate the illustrative tradition. It’s an integral part of that tradition.

Drawings such as Toulouse-Lautrec’s and Jiun Onko’s also strongly call into question Seneca’s effort to make Schulz/Toth equivalent to mind/body. Look at this example of iconic artwork.

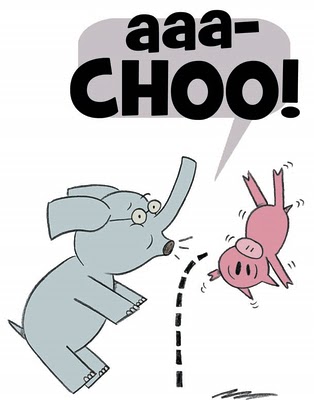

That’s a drawing by the wonderful children’s author and illustrator Mo Willems from Pigs Make Me Sneeze! Willems, as you see here, often includes dashed motion lines as part of his iconic, legible style. And what do you think my son often does when I’m reading him the book and he sees those lines?

It’s not hard to figure out; he traces them with his finger. If you look at the Toth panel up at the top there, though, nobody is going to trace that with your finger, because why would you? On the other hand, the Jiun Ito drawing or the Toulouse-Lautrec — you could see running your hand across those curves, in part because you can see the artist’s hand running across those curves. The same is true with a lot of early Peanuts; because the illustration is pared back and the linework is so instantly visible, you have the feeling of interacting directly with the hand of the creator.

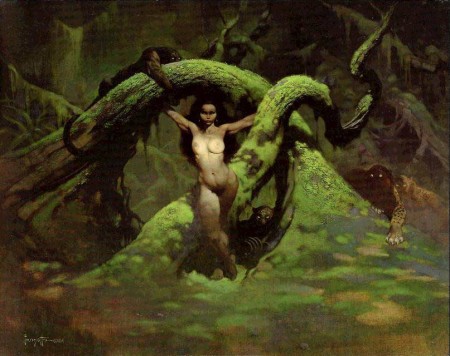

On the other hand, slick illustrational work tends to place the viewer as an onlooker, rather than pulling you in for interaction. Take a drawing like Frazetta’s Cat Girl:

You are placed as voyeur; the flesh is on display. The image is a window, the surface the line between two separate worlds rather than the place where the creator and the viewer meet. In this sense, realism can be seen not as body, but rather as body exiled to mind, while the more iconic illustrational style can be seen as mind manifested, or embodied.

The point here isn’t that Schulz and Bushmiller are better artists than Toth, or that iconic is better than realism in illustration or cartoons. Realism can be great; I like Vermeer excessively, as just one for instance. But…well, here’s Seneca’s conclusion.

What’s illustrative is how much of this environment Toth sees, the amount of visual information packed into the panel borders, the panoramic shape of the frame itself. Toth gets to his place of realness, of beauty, by piling it on, adding subtraction to subtraction to abstraction until his minimal world holds as much as the real. As much shadow, as much light, as much texture, as much scope. It’s just arranged more subtly, seen more poetically, changed into something both familiar and strikingly different. It’s art, to make it simple.

Obviously, I disagree that illustration must mean a great deal of information. I also question the parallel made in the phrase “his place of realness, of beauty”, as if realness and beauty are one and the same thing. But the real (as it were) disagreement is that Seneca equates art with muchness. What’s great about Toth is that there is “as much shadow, as much light, as much texture, as much scope” as in reality. Moreover, this muchness is arranged even more muchly than in the world — “more subtly…more poetically…both familiar and strikingly different.” Toth’s art is about getting the whole world and magically turning less into more.

Surely, though, art’s beauty is as much about curtailment as replication; as much about emptying creation as filling it. The minimal is not beautiful because it manages to get all the essential and arrange it better; it is beautiful because of its absences. What makes that Toth illustration art is not that it gives us the big world sensitively arranged, nor that it fools the eye by packing in more than can possibly be there. Rather, the art is that it doesn’t fool the eye. Instead, the blocky shapes, the distant silhouettes, encourage us to participate in pulling something out of everything — the pleasurable act of creation, which is also the act of subtraction.

So now, having disagreed with everything Seneca said, I should, in theory, conclude by lambasting him for his too narrow vision; for relating comics only to comics, and so being confused about the nature of comics, of illustration, and of art. I’m not going to do that though because — well, I’ve just been praising subtraction, haven’t I? Seneca takes a small bit of the world, turns it over, cuts it down, and ends up with a panel of flatter, more circumscribed reality. The pleasure or art in his piece is not dependent on that flatter world including the whole of the real world. Rather, the beauty is in watching and engaging with the mind that moves within the arbitrary parameters. As I suspect Seneca would agree, the point is not just what you manage to include within the lines you draw, but how you draw them.

Huh. That’s a weird passage you quote up there.

Something tangential to this bit came up in the Critics’ Panel: “Pictures that tell stories without words put comics outside the realm of the literary.” Bill Kartolopolous correctly observed that literature departments have reconceptualized themselves into “departments of narrative” which is entirely true — and something that apparently isn’t widely known? Telling a story through only pictures hasn’t been “outside the realm of the literary” since somebody first published Roland Barthes…

I’m also a little bit bewildered by the “inform/immerse” binary. What about symbolize? Analogize? Metaphorize? Stylize? All the things, for example, that those Vassos illustrations I talked about a few weeks ago do? Does he think that all visual art can do is convey story or atmosphere, or is “inform” a shorthand for “everything except atmosphere”?

Otherwise, yeah, what you said. Everybody knows by now how I feel about puttin’ art in silos.

Actually, when you disregard the “tightrope” talk, it seems to me that you and Seneca are essentially saying the same thing, Noah.

Hey Matthias. Could you expound? What do you think it is that we are both saying?

I presume you agree that we’re not saying the same thing about illustration, right? That is, he seems to think illustration is connected to realism, and I don’t. So is it the end (i.e., you think he also believes that creation is subtraction?)

“During our ominously metastasizing roundtable on R. Crumb’s Genesis, one of the big questions that kept coming up was about whether you should compare comics to other things. Is it fair to set comics next to your meatloaf… Is it okay to put them on the wall next to a crucified copy of Kierkegaard…”

My objection was to inattentive comparisons. The remedy as I saw it was to look more carefully at each work, at the story each was telling, and the context; that doesn’t strike me as recommending considering comics in isolation, and I don’t think I did that myself. Crumb vs. Kierkegaard or Crumb vs. this or that painting can be helpful if you’re aware of each complete work, and not just dismissing one for failing to hit the beats of the other. Likewise the people who came in to object to the comparisons being presented were criticizing the execution and the wrenching from context. My use of “fair” and “unfair” was about the need to pay that attention, and for critics to be clear about the kinds of judgments they were making.

Hey Alan. Sure, I get that. My synopsis here was pretty tongue-in-cheek, I think — surely I was making fun of myself as much as of anybody else. And in this essay, I’m actually critiquing Matt

hewfor failing to get the illustration context correct, right?I mean, at the end, I essentially argue that it can be fine to ignore broader comparisons in certain situations. I end up arguing against Caro — putting art in silos can be okay, at least sometimes.

I might as well say (if it’s not clear already) that I quite like Matt

hew‘s essay. I don’t agree with most of it, but it makes a lot of interesting moves which I think open up conversation in productive ways.I think when people are talking about comics the term “illustrative/illustration” tends to connotate the illustrative realism school that came from Foster, Raymond, Drake, etc.

That’s obviously what Seneca is doing. I think as his essay shows, though, aligning illustration with that school alone can lead to a very limiting sense of comics, art, and illustration.

Leaving aside your different definitions of ‘illustration’, this

“Surely, though, art’s beauty is as much about curtailment as replication; as much about emptying creation as filling it. The minimal is not beautiful because it manages to get all the essential and arrange it better; it is beautiful because of its absences.”

appears to make essentially the same point as this

“Toth gets to his place of realness, of beauty, by piling it on, adding subtraction to subtraction to abstraction until his minimal world holds as much as the real. As much shadow, as much light, as much texture, as much scope.”

I think you get hung up a little bit too much on Seneca’s emphasis on ‘classic’ or ‘pulp’ illustration, while what you’re both really talking about is suggestiveness.

I think the illustrational difference is pretty key, though (perhaps I’m still hung up on it!)

I think it looks to you like we’re talking about the same thing because it’s a dialectic; the arguments are mirror images of each other. Matt

hewis saying that the subtraction and abstraction manages to represent realness and that’s the beauty; I’m saying the subtraction and abstraction refuses to represent realness, and that’s the beauty.The issue is definitely about suggestiveness — but for him, the worth of suggestiveness is to point to the real world; for me, the worth is that it turns its back on the real world, instead emphasizing its own artificiality (which draws the viewer into the act of creation.)

Or to put it another way; I don’t think the point is that “the minimal world holds as much as the real” but that it doesn’t. Subtraction isn’t great because it leads to more but because it leads to less.

Does that make sense? I don’t think it’s an absolute, irreconcilable difference or anything (as I think the last sentence suggests). But I think it is an important distinction especially in light of the illustrative/iconic binary he’s setting up.

My comment on all this:

http://deppey.com/?p=184

Noah – I think the reason you don’t end up disagreeing with Seneca is that his essay isn’t really comics exceptionalism. What it is is comics-as-visual-art, which is, well, a duplex silo you tend to support. He uses exclusively comics examples, but his approach is art-ish. Comics exceptionalism as I use the term is really a politics more than a critical technique and it doesn’t really appear to be his politics: this is more the inverse of the problem Matthias always accuses me of, starting from literature/art instead of starting from art/literature.

I think this is evident in both his piece and yours in the understanding of what counts as Realism. In visual art, both your position and Seneca’s, illustration or otherwise, “realism” is opposed to “abstraction” in a way it isn’t in prose. In prose, realism is achieved through abstraction — exactly the same way non-realism is, because words are inherently abstract. This means that “representation” is a universal concept in prose theory whereas it is a (often used as a) more specific descriptive term in visual art.

Of course, there are approaches to visual art that understand that it’s all representation, that visual realism is really no less mediated or more immediate than visual abstraction, which is the Duchampian argument you’re picking with Seneca. But those approaches are often decried by people in visual art as “too literary” — and that’s the sense in which there is a silo here. It’s just a silo you tend to be ok with, because you get around the problems of using literary representation theory for visual art by focusing on the virtues of abstraction.

So perhaps it’s not so much a silo as a blind spot: critical practice around visual art — not meaning you! — is often just very resistant to talking about the ways in which the idea of a “true picture writing” that “carries instant meaning for the reader with no contemplation required” is philosophically naive and then offering evidence from visual art that transforms or advances the theory built on language or that lets the theory inform a more sophisticated understanding of visual art. Comics is, IMO, an “exceptional” place to investigate these “representational effects”, but not if the blind spot/silos are left intact and that definition of realism unchallenged.

Hmm. Not sure I quite followed all of that exactly…. I guess I can say I started to poke at the question of realism and comics as literature a bit and then decided not to — not so much because I agreed with Seneca as because it seemed like too much to struggle with in this post.

I do think that the comparison of comics to hieroglyphics is particularly unhelpful (since Alan brought up the issue of contextualization.) In the first place, hieroglyphs (unlike Japanese ink painting, for example) really have very little to do with the tradition of illustration as we now know it. And in the second…hieroglyphs are a language. Language represents in a very different way from images. To suggest that cartoons are actually aiming to be hieroglyphs, or to be read in that way, seems misguided.

I’m not sure if this gets to your point exactly, but one of the interesting things about visual art vs. prose is that visual art is actually *more* capable of abstraction in many ways. This seems partially because prose is so steeped in representation already; words refer directly. In some ways that makes them more abstract, but you could also see it as making them more realistic (or pointing more directly to reality.)

Here’s Matt’s Twitter response.

Toth is just a virtuoso, that’s all…

Nothing wrong with virtuosity!

The truth is I haven’t seen a ton of Toth’s work. I’ve liked it okay overall. This panel in particular doesn’t especially speak to me; I was much more interested in Matt’s response to the art than I was in the image itself. In this particular case, I’d say his essay was better/more interesting than the thing he was writing about. Though I’m sure he’d think I was insane for saying that….

How many Alex Toth stories are up on blogs these days? Thousands? Millions? It sure seems like it. At this point there’s probably decades worth of his stuff posted.

There’s nothing wrong with virtuosity, but you need to read a bit more carefully Noah. I also wrote the little word “just” and that’s a problem. Someone who is *just* a virtuoso is like a Ferrari. A perfect machine that does everything in a perfect way, but can only be as good as the one sitting in the driver’s seat.

Take that twitter as the immediate response to getting opinions put in my mouth (before I got to the end). I could go through and rebut some of your points, but that would be MAD boring to read. Glad you dug the article, thanks for writing about it, hope you’ll be back at DTU for many Mondays to come! hot stuff

oh also dude, “Matt” ain’t short for “Matthew”

I also agree with the Wikipedia: “[virtuosos] are commonly criticized for overlooking substance and emotion in favor of raw technical prowess.” Could Alex Toth put his talent in the service of hollower stories? With a few exceptions, I don’t think so.

Hey Matt

hew. My apologies for the illegitimate shortening of your name! And thank you for commenting, and for your original post. Take care.Oh, and Domingos…sometimes virtuosity can be enough — or at least a pleasure in itself (Winsor McCay is sort of the predominant comics example of that for me.)

Noah, I think Matt’s saying that his full name isn’t Matthew.

Aha! And duh. Thanks, Alex. How embarrassin’….

I think the clumsiness of the terms is muddying this a bit. As Derik was getting at earlier- there’s a wide range to what could be considered an “illustration”, but when something is called “illustrative” it’s a much more specific description, and doesn’t even apply to some things we’d call “illustration” in the first place ( as in “painting”/”painterly”). The examples by Onko, Lautrec, and Willems may well be illustration, but they’re functioning like graphic design (purposed as illustrations maybe?).

Crumb can be very abstract (ie Fritz the Cat), and at the same time far more illustrative than you’d ever catch Toth being; Pixar movies are abstract and realistic. Linking subtraction and abstraction together in your argument is also kind of clumsy.

“Virtuoso” is totally precise as a description of Toth though. Ditto for Frazetta.

Hey Chris. Well, as I said to Derik, I think the more narrow definition of illustrative ends up causing problems in Matt’s argument. My point isn’t really that he’s misusing terms, but that broadening the perspective causes a lot of his dualities to collapse.

I don’t see why illustration and graphic design should be opposed terms, for example.

The subtraction/abstraction is somewhat an extension/borrowing from Matt’s article, I think.

I don’t quite know what you mean by abstract and realistic. Pixar movies are cartoony and iconic. They aren’t abstract, in the way that that term is usually understood (nonfigurative.)

The thing about Toth, I love his style, and when he’s on, his visual storytelling skills are excellent, but the stories he’s telling are mostly utter crap. He’s better to look at than to read.

fwiw, I wasn’t trying to say that Noah’s examples aren’t illustration, just that in the context of most comics discussions, illustration has the connotation of one particular kind of illustration (coming, again, from the old newspaper realists and, I’d imagine, the fantasy illustrations of a certain period).

“Illustration” as a term can have a pretty broad use. Any comic can be considered “illustration” as can most ads, book illustrations, diagrams. The point seems to be that the “illustration” does not exist as its own independent image. It’s part of a larger whole (book, ad, comic, etc.) rather than just a drawing or painting that exists as a singular piece.

Noah:

That’s exactly why Winsor McCay isn’t in my personal canon. I don’t think that virtuosity is enough to call an artist great.

On the other hand, McCay isn’t *just* a virtuoso. Even if I think that comics history goes back to ancient Egypt, McCay was lucky enough to live in a time and a place when and where comics and animation were developing enormously. He was one of the key figures in that development…

Unfortunately I didn’t buy Ulrich Merkl’s _Rarebit Fiend_ book, so, I can’t say if the essayists did some overinterpretations in there or not, but they found some substance in the series. Or so I heard…

Well, but Domingos– it seems that you are assigning

literary value or seriousness of subject matter as the criteria for artistic worth.

I wouldn’t class Toth as a virtuoso, but as a master. A virtuoso is a show-off.

Good point, Toth isn’t a show-off. What I meant about work being abstract and realistic is that you can be dealing with abstracted shapes/forms, and treat them with a high degree of realism. Fritz the Cat being as simple an abstract cartoon shape as Mickey Mouse, but rendered with the same degree of realism Crumb applies to anything else (the texture, lighting etc). Same with the Pixar example, abstract 3-dimensional shapes, subjected to all the subtle effects of reality (multiple light sources, dust in the air, objects out of focus, etc). Maybe I’m misusing the word abstract though, I thought there were degrees of abstraction. Aren’t cartoons forms of abstraction? My bad.

Alex:

I disagree: if an artist is doing nothing very well s/he’s showing off.

Chris, abstraction is kind of a contested term. I think Andrei Molotiu goes for a pretty hard-core definition as not at all figurative. There can be some give on that, but generally I think it means moving away from figuration. I don’t necessarily think that something like Peanuts is exactly abstract, since the forms are clearly meant to be figurative, even if they’re less realistic than, say, Frazetta.

The Onko drawing is pushing towards/playing with abstraction, I think.

Caro and Derik may disagree with my take on abstraction though….I don’t think I actually use the term in my essay.

Domingos, there were some efforts to find more meaning in the Rarebit Fiend book.I didn’t find them convincing, necessarily. I talk about that here. (It’s one of the two essays of mine Jeet is willing to admit to liking!)

Oh, and art is always performative; if you’re doing art, you’re kind of showing off. I don’t see anything wrong with that.

“Abstract” is one of those terms (like “illustration”) that seems quite open to interpretation.

Andrei’s use of abstract in the Abstract Comics anthology is much more in the vein of abstract expressionism, a pure abstraction that is outside of any representational purpose (ie it’s not supposed to look like something).

I would consider Peanuts to be abstracted. It’s not pure abstraction, but there is a simplification of form that fits the conception of abstracting something (as in the “abstract” of a scholarly paper). Though I think this is more often considered “iconic”.

So we might perhaps better refer to iconic abstraction (Peanuts) and pure? / non-representational? abstraction (Molotiu’s Nautilus).

Noah, if abstract is a move away from figuration, is a still life abstract?

Well, figuration would be broadly “looking like stuff in the real world” wouldn’t it? I mean, an apple has a figure.

Your definitions seem fine to me. I’m much more resistant to calling “illustrative” realistic; that seems to conflate medium with style in a way I think is really unhelpful.

Andrei Molotiu does abstract comics, but he has a more liberal understanding of the word in his anthology (cf. for instance, “Abstract Expressionist Ultra Super Modernistic Comics” by R. Crumb or “Because” by Jeff Zenick). These are non-narrative in my book, not abstract.

Noah:

You may be right about showing off, but the “showing-offness” is inversely proportional with the substance. I. e.: in a great work of art it’s a means, in a circus it’s an end in itself.

I wrote a long response to Noah’s question and it looks like the conversation has moved on a little bit, such is the joy of comments. They’re so dialectical! ;)

I don’t know which bits you didn’t follow, Noah! The question about realism is definitely a lot to struggle with. But it’s also, IMO, almost exactly coextensive with the line separating visual art theory from literary theory, which is why it feels like a silo and why Matthias and I go ’round and ’round with it. Even a literary white-hair as out of touch as Harold Bloom wouldn’t think of uttering that sentence about “no contemplation required.”

I guess here’s what I was trying to say. You have this very intuitive understanding that abstraction can be as “realistic” as figuration. That statement, I would say, is a visual-art-phrasing of a fundamental axiom of “literary theory” (at least of post-structuralism, but that’s pretty pervasive.) It’s a pretty decent definition of “post-realist” philosophy, which is largely our shared vantage point. The idea of “abstract realism” is something that comics really hasn’t wrapped itself around, even though comics is really very well equipped to do so, as an artist like Feuchtenberger readily demonstrates.

I think because this is so intuitive for you, you readily accept the inverse when it’s stated outright: the recognition that representational art is likewise every bit as artificial as abstract art. That’s Duchamp, but it’s also the counter-intuitive bit that Seneca doesn’t get, why his take on illustration is actually different from yours and why the “dialectic” (would I call it that?) that you describe to Matthias is apt.

But what happens even in your “comics-as-visual-art” perspective (at least in this last post) — where our vantage point is less shared — is exactly what Matthias points out: “suggestiveness” becomes a direct effect our experience of certain visual attributes. For Seneca, it is treated as though it is immediately meaningful, and your explanation about how abstraction is beautiful feels too close to that vantage point. You’ve imbued the things that were used in conventional visual art to signify artificiality with the sensual and psychic attributes that conventional visual art used to signify a kind of humanistic reality. I completely agree with you aesthetically, but I’m more insistent that our position is fictional and artificial than you are.

The literary theoretical perspective demands fealty to the idea that any artistic “suggestiveness” is fully artificial, always “abstract,” never “real.” That’s the distancing gesture that Seneca doesn’t make at all and that you resist making, although you get much much closer to it than he does. That distance is an outcome of accepting the notion that the mediation of “representation” is a universal.

Some of this is what you’re getting at when you bring up the “ease” with which visual art handles abstraction. The word you probably want is “indexed” for the “pointing to” quality of language’s relationship to reality. Language is indexed to (some common understanding of) reality. Words are assigned meanings and used as pointers for those meanings. Images are not indexed; they’re, I dunno the word I want here, maybe sensual. That’s why it’s been so hard to come up with a satisfying visual semiotics: I think the notion of an “icon” is just palpably less satisfying for explaining how images can make semiotic sense than the sign is for explaining words.

But just because images aren’t indexed like words are doesn’t mean they’re this direct path to some essential human something or other. That’s precisely why the hieroglyph comparison for Seneca’s naive notion of “picture writing,” is more than unhelpful — it’s actively misleading. If it’s actually picture writing (as heiroglyphs are), then it’s transforming the image-unit into the sign-unit or it’s not actually working like writing. Picture writing isn’t any more unmediated than word writing. It works as writing because it’s indexed, which makes it into a sign.

The idea that pictures can take on signification, whether simple or the more complex communication like narrative, in the same way that language and writing do, without taking on the properties of language and writing — the indexing and its effects — is naive. People think drawing is this other thing. But images that do semiotic work, that “inform,” are semiotic entities. They’re indexed to a different system from words, but the act of making them do narrative work is the act of making them into signs. And the moment that happens, you’re squarely in this realm that “literature” has carved out for itself. All the caveats and qualifiers and philosophical aporias that continental philosophy identified still apply – it’s only the mechanism that’s different, and the caveats and qualifiers and aporias in almost all cases have very little to do with the mechanism. Talking about art as if realism was intact is one way of maintaining those silos between the different arts.

I should say that in literature there’s a popular version of post-realism as well as the more rigorous philosophical one of theory. The formalist self-awareness of literary technique is consistent with these theories without necessarily being overtly engaged with them. Literary technique, though, has several levels: the mechanisms of crafting living sentences and paragraphs (maybe the art parallel is figuration), the mechanisms of crafting narrative structure (composition), and then also the manipulation of that composition to make something that is meaningful in a similar way as the sentences and paragraphs. In art, that latter is abstraction — but in modern literature, it’s always there. There is always a level of abstraction at work. Nothing is ever fully figurative, fully realist.

Conceptual art, video art, performance art (the ones you name) have cultivated a highly sophisticated and medium-specific formalist self-awareness that achieves that same thing and is also consistent with “theory”, but visual art theory hasn’t really caught up with the artists in those fields. Comics hasn’t really cultivated that kind of top-level-abstraction yet in theory or in practice: there’s a self-consciousness about form — I think that’s very fully on display in Seneca’s piece — but it’s still from the vantage point of visual technique, the sentences and narratives. That looks and feels to me like a silo.

Domingos:

“I disagree: if an artist is doing nothing very well s/he’s showing off.”

This isn’t very clear. Do you mean an artist who is incompetent– who can’t do anything very well — is showing off? Or that an artist whose ‘content’ is totally vacuous is showing off?

Either way, it makes little, if any, sense.

When I say a virtuoso is a show-off, I mean s/he makes an exhibition of skill designed to elicit admiration for the exhibition itself, regardless of the work of art involved.

Examples:

The violinist Paganini would play in concert a difficult piece, and then, progressively, cut one string of his violin after another until he finished the piece on a single string.

That puts me in mind of a tale of the Buddha. He was told the story of a holy man who had requested free passage on a ferry across a river. When the ferrymen refused, the holy man crossed the river on foot: walking on water– a miracle.

The Buddha was utterly contemptuous:

“That miracle wasn’t worth the copper coin the ferry would have cost.”

In painting, Michelangelo’s mastery of the contraposto (bodies twisted in two directions) led to extravagant manneristic manifestations of this technique.

In acting, there has arisen an “Oscar-bait” culture of actors taking on exotic roles, such as Dustin Hoffman’s as an autistic savant in ‘Rain Man’– for which, indeed, he won an Oscar. William Goldman has opined that if anyone deserved an Oscar for that film, it was Tom Cruise; and that’s not as counter-intuitive as it appears.

Speaking of cinema, there’s the case of Alfred hitchcock and ‘Rope’; this film was shot entirely with uncut 10-minute takes, a technical tour-de-force; one that Hitchcock always regretted as unnecessary posturing– as empty virtuosity.

And in comics? Search for Ruby Nebres on Google Images, the apotheosis of perfected, empty craft.

Alex Toth never showed off. He always subordinated his art to the story; yes, it’s regrettable that that story tended to be banal. But he never gave in to the temptation of visual pyrotechnics.

He’s well-known for his graphic minimalism, but he never pushed that– never implicitly proclaimed, “Look how sparse I can make my drawing while conveying all the information needed!” In fact, where necessary, Toth could be very detailed; he by no means shunned hatching and cross-hatching where called for.

Domingos, you should refect upon your use of terms like ‘virtuoso’ and ‘hack’; sometimes I feel you deploy them as means of crushing discourse, without suitable refection on their true meanings.

Alex: “Alex Toth never showed off. He always subordinated his art to the story; yes, it’s regrettable that that story tended to be banal. But he never gave in to the temptation of visual pyrotechnics.”

What doesn’t make sense is this: “He always subordinated his art to the story.” The art is also the story. There’s no subordination. I’m not even against pin-ups. I, for one, don’t mind losing myself in a splash-page. I know I shouldn’t, but I even call that “reading.” I say that I shouldn’t because, according to Caro: “People think drawing is this other thing. But images that do semiotic work, that “inform,” are semiotic entities. They’re indexed to a different system from words, but the act of making them do narrative work is the act of making them into signs. And the moment that happens, you’re squarely in this realm that “literature” has carved out for itself.” This is like some sort of colonialism in which words colonized the narrative continent. I don’t mind calling literature to wordless stories and I don’t mind saying that I read images (I’m no essentialist). It’s just the arbitrariness of it all that’s a little bothersome. In the same spirit, if a text describes something why can’t we say that it entered a realm that the visual arts carved for themselves and call it a drawing or a painting?

Anyway, back to Alex & Toth: I agree with everything you say about virtuosity and I agree that Toth is no MacFarlane, or something (hardly a virtuoso, though)… However, there’s a problem with a couple of your examples: there’s no pyrotechnics in Alfred Hitchcock’s _Rope_ (you called it a “technical tour-de-force,” but that’s not a synonym). Dustin Hoffman did no overacting in that particular film, methinks (maybe overacting is pyrotechnics?). Toth’s drawing/stories were brilliantly executed nothings. That’s as good a definition of virtuosity as any other in my particular dictionary. This is just semantics, though… and it’s hardly interesting…

As for my last use of the word “hack” on this blog I thought that it was obviously written in tongue-in-cheek mode. Oh, well!…

Alex, that’s a great story about Paganini. He was such a rock star. (Dustin Hoffman though…blech.)

Domingos, texts entering the visual arts realm and being called drawing or painting happens all the time. This for example. (Note that description isn’t the key here, though.)

Caro, thanks! ! I followed that better.

I think the Onko piece actually speaks directly to a lot of these issues. The calligraphy means “Not Know”, which is a Buddhist ideal in some ways. On the one hand, the piece shows abstraction as not knowing (opposed to reality) since the figured figure is flagrantly not there. On the other hand, the piece is about the inability to avoid making meaning — you can’t not see the figure there (and if you’re Japanese, you can’t not read the hieroglyph, which conveys knowledge about not knowing.) So art and writing both convey meaning in a way that is automatic, and indeed inescapable…yet the very visible brush strokes demand you see art/writing as tied to the creator, which is to say, as a created or artificial product.

Similarly, the piece deliberately shows how art and writing are the same (the very kinetic and evocative brush strokes of the words make them look like active figures; the outline and abstraction of the figure make it look like a Japanese character.) The parallel emphasizes the differences too, though — not least for those of us who don’t speak Japanese, and so can parse the image but not the words.

The bit in your comment I’m still a little stuck on is the tripart literariness and how it maps onto art or cartooning and abstraction/figuration. That is, you say literature has three levels: sentences/paragraphs; narrative; and structure/symbol (I think?). You say that the structure/symbol is the part that would be considered abstraction in art? That seems really weird to me; I mean, the structure/symbol level of meaning in art would be structure/symbol, wouldn’t it?

This also confuses me “There is always a level of abstraction at work. Nothing is ever fully figurative, fully realist.” You say this in reference to literature, but surely it’s true in art as well? Or is your point just that art theory doesn’t embrace this insight as fully as literature does? (Which I’m really not sure is the case…? I’d agree that comics criticism hasn’t really done so — though certain comics artists probably have.)

Domingos:

I actually would and do say something very close to this last about Delillo, recently, especially a book like The Body Artist.

But it isn’t arbitrary at all to expect that when comics critics talk about “narrative” and realist illustration and representation and abstraction that they not be completely naive about 20th-century post-realism. Film critics quite frequently talk to ordinary people in ordinary non-jargony language about critical abstractions without saying things that sound like they’re living in the 19th century.

The approaches and understandings of “literature” as the study of narrative (and a constellation of related abstractions) have emerged out of a conversation among philosophers (of language and of mind), linguists, anthropologists, and scholars of writing. It’s not about “words.” It’s about semiotics and meaning and representation and all kinds of abstractions, and it’s about how you manipulate those abstractions in art.

But when we talk about visual art, those conversations tend to be treated as happening just among writers and students of writing. And unfortunately, visual art theory — that is, writing by people who self-identify not as “philosophers” or “theorists” but as “visual art critics” or scholars — really hasn’t contributed all that much to the conversation about narrative and representation that literature has been having with philosophy since 1968.

Now, what visual art theory has contributed tends to be quite extraordinary and brilliant, and obviously it’s perfectly fine for visual art to have its own native approaches, especially in pure visual art that is not narrative. But when there is narrative, especially narrative as conventional as most comics narratives, ignoring those conversations is just naive and kind of hard-headed. Film is a visual and narrative art, and it doesn’t ignore them — film’s contributed so much to them that literary critics can use film theory to explain aspects of literature!

It’s ok to write a naive, old-fashioned narrative, but to advance the idea that the “ideal comics” shouldn’t be aware of those conversations and should conform to 19th-century notions of narrative and meaning etc., well, the nicest thing I can say about that is that it’s a silo.

Aha! Don’t reply to the last paragraph of my last comment; I get what you’re saying now.

Noah — Posts crossed — more to come but this bit is easy:

I think it’s true in art as well, but I don’t think Seneca’s opening paragraph sounds like he’s paying much attention to it. Which is my point: art theory doesn’t embrace it as fully as literature, although it does embrace it. Comics criticism tends to be really enamoured of some very old-fashioned notions about realism, which it often defends on the grounds that it’s “art not literature.”

Dudes, that’s bogus.

Noah:

I know about Kosuth and Weiner and Barry and Huebler (I feel like an old fart! Sorry for the namedropping!)… Their words are considered visual art because they’re in a social visual arts context (also, they’re amplified on a wall).

I meant a description in a book or magazine.

Caro:

We agree, as usual.

Your post stresses my point. It’s an historical fact that comics criticism didn’t develop while lit crit and film criticism did. That’s where I see arbitrariness. And that’s also why I see colonialism. Like some 15th century discoverer literature arrived first and colonized the narrative continent. The newcomer, comics, has to use lit crit’s words to define objects or actions that shouldn’t be lit’s property. If the conversation is about semiotics and meaning, not about words, the conversation is about all art forms, not just literature. Concepts like “narrative” or “reading” should not be lit’s property (maybe we could use “decoding” instead of “reading,” but the habit tells us that such a word is a bit awkward; same with “narrative figuration,” sorry Will!). This happens all the time though: musicians use Italian words to this day. Maybe because of Monteverdi et al…

I don’t want to exclude anyone, but you know what they say: everybody’s a critic (especially on the Internet). Maybe we should be discussing the real comics critics: Umberto Eco (I’m sure that he didn’t have old fashioned conceptions about naturalism – I prefer this term to “realism,” a politically charged word in the visual arts), Jan Baetens, and a very small etc…

PS Have you heard the one about comics being the last refuge of figuration? Haw haw haw…

Yeah, tell that to Andrei Molotiu…

Alex, I think Andrei would agree that abstract comics are a lot less accepted/established than abstraction in other media.

Domingos, I think it’s weird to think of using terms from literature in a comics context as imperialist, or as threatening comics integrity or some such. The lines between mediums aren’t borders, and art forms aren’t political entities. Critical borrowings happen all the time. Using literary terms and ideas would help comics — and would help literature too, in that it would allow comics to be part of a conversation where it, like film, could contribute to the understanding of narrative and abstraction across art forms.

One of the things I liked about Matt’s piece is that it’s actually engaged in these issues in a way that’s not all that usual for comics crit. The piece is about realism, abstraction, what we expect from art, how minimalism subtracts through adding, etc. I think Matt probably would have benefited from having a better sense of what other people have said about these things….but I also think some questions he raises (how do pictures generate meaning differently from text/how do they generate it in similar ways/how is this related to abstraction) are ones that comics is actually better positioned to confront than lit theory. Which is why I was interested in writing about the post, I think.

Could Alex Toth put his talent in the service of hollower stories? >>>>>>

This is the same criticism that has been levelled many times at Toth…of course the stories were hollow, that was the only stories offered to Toth, the only stories there were in comics. If he hadn’t drawn hollow stories, he would not have drawn any comics at all. By the time the writing began to “improve”, he was done, his wife’s death and his own perfectionism had made it impossible for him to work. In any case the panel that Seneca used to make his point is from a particularly compromised effort, one of Toth’s very last comic stories which was rejected in its original version, then the artwork was cut apart without Toth’s involvement and repasted togther to make an entirely different story. In other words, the story that was printed has little relation to the story Toth drew, so his work here cannot be analysed with any degree of accuracy.

Hey James. That’s fascinating. I wonder if Matt knew that the story had been butchered? Do you think it actually affects the reading of this individual panel? (You seem to be saying it does….)

Yes, I remember reading about that in an interview with Ernie Colon. Colon, then an editor at DC, had commissioned the piece and was happy with the result. For some reason, Len Wein intercepted the story and had its panels cut up and reshuffled…apparently for Colon it was the last straw.

Noah:

Frankly I don’t know why you’re implying that I mind borrowing words from literature when talking about comics? Or film, for that matter. I don’t know if I ever did such a thing, but I can see myself talking about “the camera” when describing a comics sequence (there’s no need to reinvent the wheel). When I talked about lit crit colonizing what I called the narrative continent I didn’t mean to say that it’s a bad thing. That’s just what happened. Here’s what I also said: “I don’t mind calling literature to wordless stories and I don’t mind saying that I read images (I’m no essentialist).”

James:

I understand what you’re saying. One of my pet theories is that a lot of talent was wasted because comics was such a low regarded medium during the 19th and 20th centuries.

Here’s one of my all time favorite stories (to go on with my Ferrari metaphor, the driver did a great job this particular time). Toth’s comments are fascinating: what a perfectionist!…

http://tinyurl.com/385m4so

I think it is hard to read a panel outside of the context of the words IN the panel and of the story it is in. The art in comics is not illustration but rather dovetails with the text to create a greater whole which is the complete statement, the story. So analyzing individual panels is fairly pointless, even in a piece that has not been butchered as this Toth story was.

Domingos, think I just misunderstood you. My apologies.

James, that makes sense with what you said in your article. I guess I wouldn’t be as hard core as that. It seems like you can analyze a sequence (or even a still) from a film, or a sentence or paragraph from a book, so it seems legitimate to look at a panel from a comic — especially when you’re using it to open up philosophical and representational issues which aren’t necessarily tied directly to narrative, as Matt is doing.

It differs from the analysis of a film still, as a panel is only a portion of the composition of a page, or of two adjoining pages if the entire spread is utilized. By my estimation, the entire page is a larger composition. But, some artists just stack panels of a uniform size (Toth himself has done that), so perhaps in that type of structure one could isolate a panel as a unit.

However, if one must analyze an individual panel, the lettering is part of the composition, of the art. One cannot seperate the art from the words and their meaning, the art and text together form the intent of the panel.

In regards to James and comment #46–

I own the Toth piece that contains the frame that is reproduced here. Although I cannot vouch for the rest of the story, that particular page does not have panels cut and reshuffled. There are various balloons that are pasted over the original art, but the drawn sequence seems to be in place as Toth pencilled it (I’m not absolutely sure without looking up the credits, but I think Terry Austin inked the story).