Last Saturday, at one o’clock in the afternoon, fifteen Seattle cartoonists packed into a sunlit room at the Phinney Ridge Community Center for a twenty-four hour annual ritual. Burdened with snacks, lap boards and drawing supplies, everyone seemed a little unsure at first confronting the empty room. But soon the mood changed as tables and chairs were pulled out and adjusted and windows and blinds were open to let in the last few hours of light.

For my part, I had built up quite a bit of excitement before the event. I would be participating in a group organized by local cartoonist Henry Chamberlain, and consisting of several cartoonists and illustrators whose work I was familiar with, including Jennifer Daydreamer, Tom Dougherty, Eroyn Franklin, Marc Palm, and David Lasky, whose story “Minutiae” is the best 24 hour comic I’ve ever read. So it was with much and excitement and a little trepidation that I began.

The Challenge

The twenty-four hour comic has become an international event and challenge, the comics equivalent of the Ironman competition, with possibly less vomiting and long-term physical wear on the participants. Cartoonists answering the challenge commit to producing a twenty-four page comic within a twenty four hour time period. Plenty of digital ink has been spilled documenting 24 hour comics events, but very little has been said about why such an exercise might be useful, what effects it has on its participants, and what type of impulses it stems from.

Like any good super hero or villain, the 24 hour comic challenge has a secret origin story that neatly ties into its purpose. Scott McCloud’s parents were traveling acrobats killed by the nefarious was at a signing in Boston watching his friend Steve Bissette, commonly regarded as the slowest artist in comics, whip out sketch after complex sketch. And it occurred to McCloud that if Bissette was capable of responding to fan requests so quickly, could draw so fluidly on the spot, then there was no reason for his glacial page production In fact, he could probably do an entire comic in a day. And so, the challenge was born, McCloud and Bissette each completing a full twenty-four pages plus a cover in two very lonely twenty-four hour stints.

It might have stayed just a private challenge between friends had Bissette not sent copies of his completed comic to Dave Sim, who took up the challenge himself and published the results, along with excerpts of Bissette’s and McCloud’s, in the back pages of Cerebus. From there it grew uncontrollably, spreading far in the cartooning world and even jumping media, until it seems like some variation has infected every art form (National Novel Writing Month, 24-Hour Play, etc).

So what’s the appeal of such an activity? If you go by just on what people have said about it, you’d think that it’s primarily the marathon aspect of it- ask a cartoonist and you’ll likely get a description of how tired he was by the end, or a list of the junk food consumed, or the very real panic setting in when she realizes that she’s several hours behind and is unlikely to catch up. So is there any artistic point to such an activity, or is it a glorified sleep-over with more ink-slinging and less fort building?

Even at its genesis the challenge was about working past self-imposed limitations and, as McCloud put it, finding out “how much you can actually draw in an hour.” But it’s more than that- many artists who have taken up the task, like McCloud himself, also have used it as an exercise of improvisation, skipping over the “normal” learned, adult practices of plotting and designing and layout and sketching and just getting down to the business of making comics. In a certain way, it’s about ceasing to be an adult, and returning to an earlier mode of creation.

When Kids Make Comics/ Ultraman Soccer

It’s like seeing kids playing soccer, and one of them yells out, “I’m Ultraman,” and they all join in a game of make-believe, while still kicking the ball. Are they still playing soccer or are they now playing Ultraman? Or something that is both?

-Furuya Usamaru

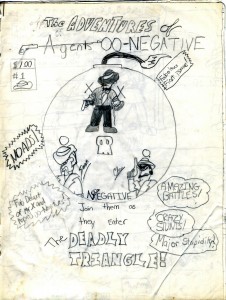

The first comic I ever worked on was started at a sleep over at my best friend Chris’ house in the fourth grade. It was entitled “the Adventures of Agents Double-O Negative,” title stolen from a lame joke in the movie Goonies. Like many children’s comics, it involved a large amount of self-insertion, each of the main characters having the same names and rough features as their creators (although each also had rather fetching mustaches). Chris and I worked on it that night, and completed it after school sometime over the next week. Like many of the young cartoonists I have worked from in the years since then, we proceeded with very little plan or concept of the outcome, working on the comic panel by panel, page by page, until we arrived at the number of pages we had pre-determined it would take to constitute a “real comic”.

Our working method would be considered fairly unusual for adult cartoonists in that both of us worked on both the art and the writing, primarily drawing “ourselves.” Because we both had input into both aspects, it also meant both of us being able to veto each other’s ideas (after an early page where the two men’s “cheif” is killed in a “nucular explosion”, I distinctly remember Chris wanting a panel or two of the protagonists playing basketball with his skull. Alas, it was not to be, as I thought it would make them too unsympathetic.).

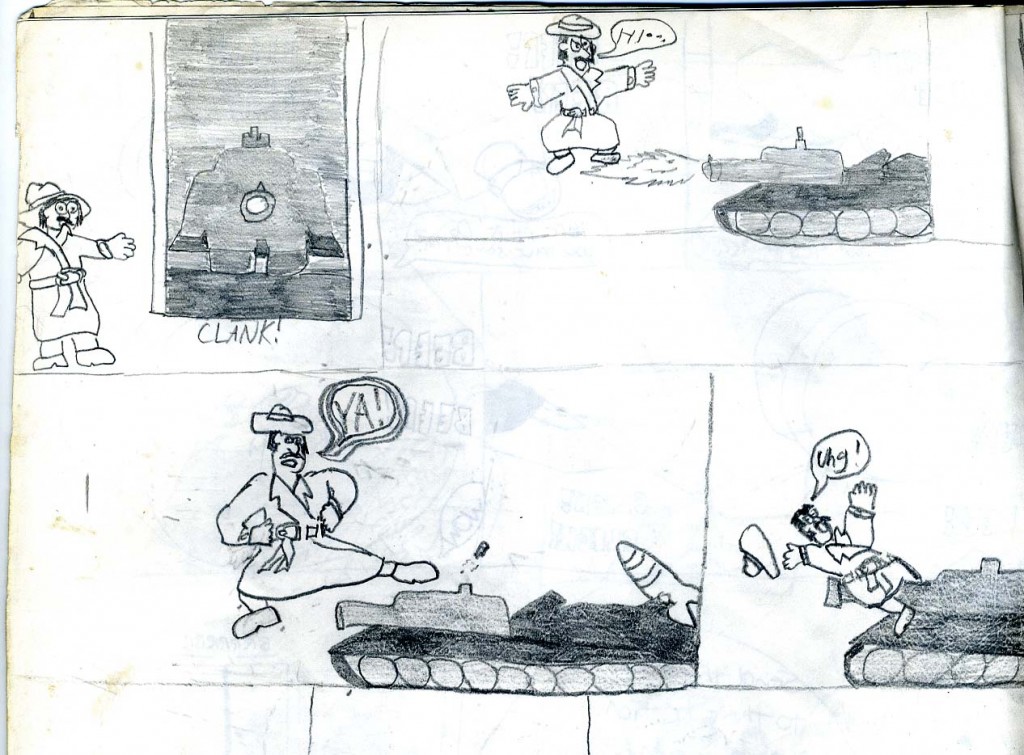

- a rousing action sequence from “the Adventures of Agents 00 Negative”, by Chris M and Sean Michael Robinson, age 9

The simple fact is that a challenge of twenty-four pages in twenty-four hours is a ludicrously simple task for a child- they have the necessary combination of unbounded imagination and unselfconscious drawing abilities. A young artist’s drawings are very close to a certain type of cartoonist’s sensibilities in that they see the visual world in a very diagrammatical way- a child reaches for the symbol of a thing rather than a literal visual depiction of the thing itself. At an early age, practically from the time that a young artist is first asked “what is that” in relation to a page of scribbles, they begin to rehearse the marks by which they will represent a face for the next few years, and many for the rest of their lives.

But along with adolescence, at least in our photophilic culture, comes an impulse to create images that bear a closer visual relation to the outside world. And these uncomfortable juxtapositions of observed detail and symbol-system-hangovers end up serving neither master, and the young artist’s uneasiness with this combination ends many an interest in drawing. The ones that continue, however, often split into one of two camps- taking the observational-drawing, “studio art” route, or taking the route of the often self-taught cartoonist, copying the drawings of their favorite artists and slowly working out the mechanics of that artist’s personal symbol system.

The Quitter and the Artist

In middle school I was one of the drop outs, dissatisfied with my drawing and distracted by music, an area in which I had some actual verifiable success. I still drew in private, copying my favorite panels from the terrible superhero comics my friends and I read at the time (I still have a notebook full of copies of Rob Liefeld, Adam Kubert and Art Adams drawings). And every once in a while I would work on something new, showing it to our school’s local celebrity cartoonist, and new best friend of my former best friend, Jared Hodges.

Even in middle school Jared seemed to have that rarest of cartooning abilities, the file folder of poses in his brain that he could pull out to suit whatever he needed at the time. His visualization was incredible- he could draw the basic gesture and attitude of a pose without any reference. He and the group of friends that I was now on the periphery of worked on various comics throughout middle school, but I never saw a finished product. Certainly I never personally finished any comics in middle school. As far as I know Chris had given up drawing completely. As we had aged, our standards had changed, and this change had meant we were incapable of completing any work, and likewise incapable of improvement.

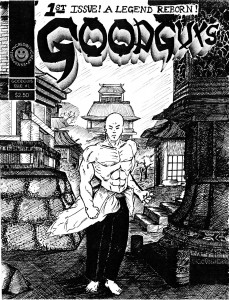

I lost track of my fellow cartoonists in the transition to high school, and it wasn’t until three years later that I had any interaction with them at all. It was the fall of 1996, and they had recently completed a thirty page comic, “Good Guys,” based on self-insertion parody superhero-ish characters created and argued about over the lunch table years earlier. The interior cover sports the telling subtitle “The quest to complete a comic in two years.”

So what happened? How could it take a group of two or three people two years to complete thirty pages, even considering the amount of time taken up by school and other activities? For one thing, the art has significantly more polish- it’s inked, with lavish application of texture and surface rendering. Additionally, the artwork itself was now being produced by one artist in isolation, rather than several friends working in tandem on the same project.

This transition was not isolated to my particular group of friends and acquaintances- fellow Seattle cartoonists Tyler Hill and Calamity Jon Morris both told me that their friends worked on long form comics in elementary and middle school years, but, as Tyler put it, “the slower, more meticulous I got with the artwork, the shorter the comics got.” This slowness of the rendering process is bad enough for young students that might have pursued the studio art route, but it can be deadly for a cartoonist, who have a few specialized skills that can only be practiced by actually making pages.

Just Do It

The cliche (which isn’t a cliche, it’s the truth) is that you have two thousand bad pages in you and until you draw them, you won’t start producing good pages.

-Dave Sim

So back to the fall of 1996. I ended up in a class with Jared and his friend Kevin, and the two of them decided impulsively to make a comic as quick as they possibly could- no discussion, no fuss, just Jared drawing with a pen and handing it off to Kevin, who filled in the dialogue. I chipped in.

As Jared would be working as a cartoonist for TokyoPop only eight years later (co-creator/co-artist on the excellent three-volume series “Peach Fuzz”), it’s not surprising that this impulsive work was a manga parody. “Giant Sized Tomato Seed”, is a goofy send-up of Masamune Shirow’s “Appleseed”, and follows in his style in that it is largely incomprehensible without large amounts of notes filling in the blanks and supplying explanation for the unclear action sequences. It is also filled with some spot-on parody of Shirow’s pseudo-philosophical dialogue, such as “You can’t arrest me. I have no brain, so I don’t know right from wrong. Don’t rupture my roast dude!”

The content is beside the point. The cover boldly proclaims, “Five hours in the making!” and that was its purpose. In a few class periods I had assisted in producing more pages of comics than I had drawn in the previous seven years combined.

Reunited the next school year in a physics class, Chris M and I set out to do the same thing on a larger scale. Using mostly time in our physics class, I would draw pages in ink and pass them back to Chris to script. As the story accumulated pages, an overall plot seemed to be emerging, and we discussed and argued about it over lunch. By May we had accumulated almost fifty pages of comics, self-consciously juvenile and exciting, and referencing many of our elementary school creations and exploits. We called it “Ninja Epic.”

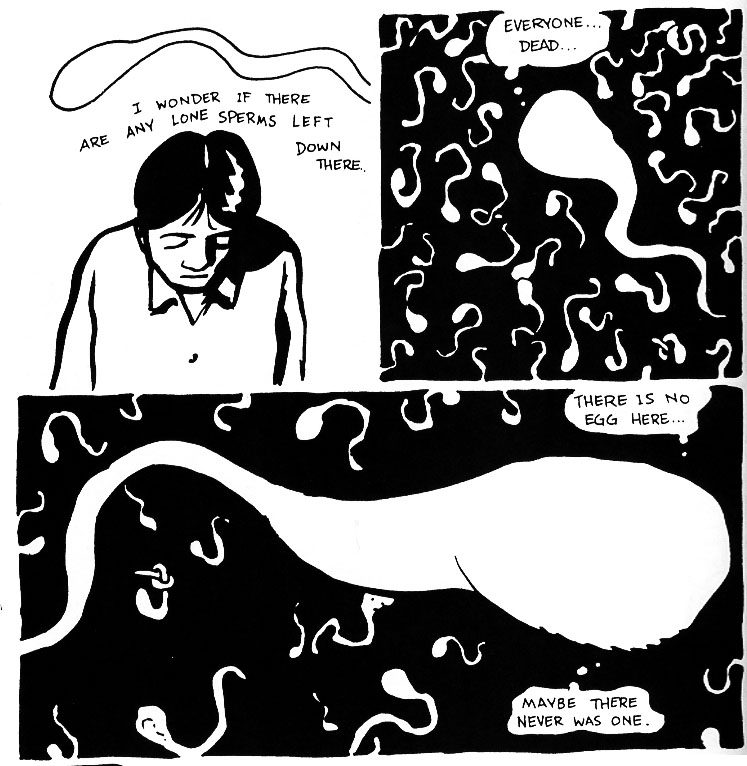

- From “Ninja Epic,” a high school improvisational comic. Masume the Ninja and Cindy the Telepathic Girl are traveling to Tibet when they meet Masume’s childhood friend, Goldie the Ninja Horse, who… nevermind.

We printed it on prom night at the local Kinkos, and the next week pushed copies on our bewildered friends, one of whom asked delicately, “Is there something wrong with the printing?”

Before our friendship flamed out again two brief years later, Chris and I tried to start a wide variety of comics projects with a slightly higher level of polish, but none of them ever got past a handful of pages, largely due to the same issues of insecurity and pretension that made things so difficult before. In the meanwhile, however, I continued to work on my observational drawing skills, and we cranked out another fifty-odd pages of improv comics.

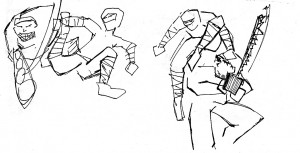

- Practice in visualization and layout, or a distraction from Physics class? From “Ninja Epic”, Chris M and Sean Michael Robinson, age 18

A Group of Adults Builds a Blanket Fort

It’s been a decade since the Ninja Epic, and five years since my self-avowed-non-drawing-wife and I made our first 24-hour comics during Hurricane Charley. In the intervening years I’ve completed approximately 400 pages of comics, and participated in countless variations of jam comics with my students and peers and friends. So how does the 24HC change at this stage? What does someone who’s now regularly making comics get out of the experience?

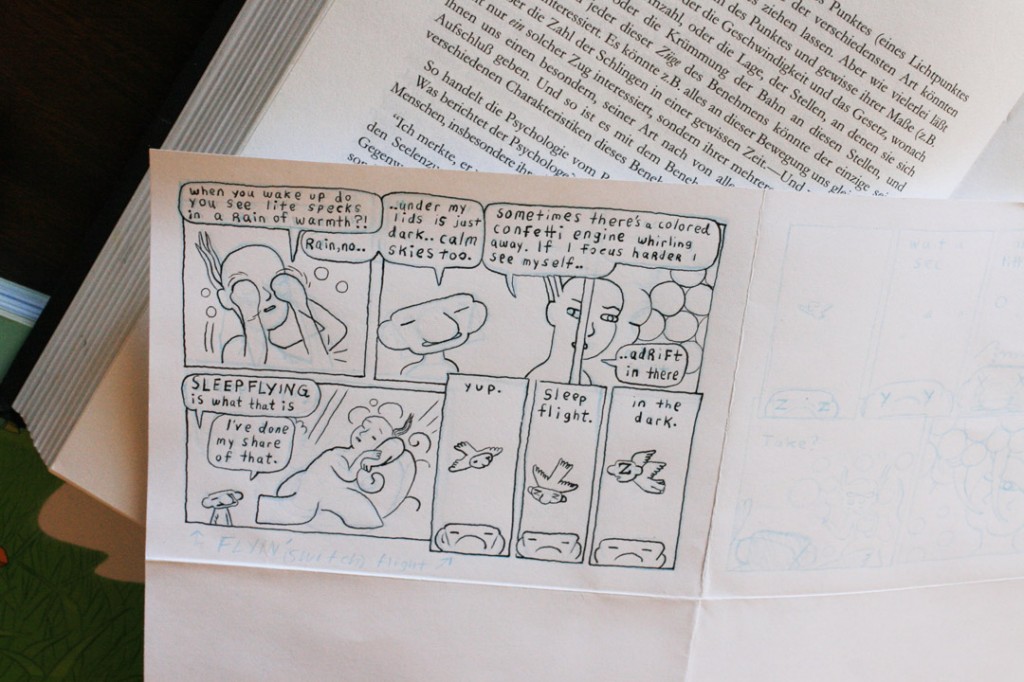

This time around I had an early sense of panic and anxiety that within the first hour gave way to acceptance and a pushing, pulsing tempo of creation. Knowing that a timetable is involved, knowing that the deadline is firm and very real makes you draw faster, and surprisingly, faster does not necessarily mean worse. It just means faster. And yes, you’ll have less surface fuss and less rendering on each page, and so the drawing can be very naked compared to a more “finished” page, but that doesn’t necessarily have to be a bad thing, either. Inking at a breakneck speed can result in some surprising revelations as well, not all of them pleasant (pleasant- hey, so that’s why I’ve never been able to make that kind of line- it’s just a faster stroke! Unpleasant- trying to ink with a brush (i.e. no surface resistance to steady your hand) after having been awake and working for thirty hours)

Most important for me was the realization that this feeling was what focus was really like. That each time I sit down at my drawing board with NPR turned on in the background, with the internet only a chair turn and a few clicks away, with cats pleading at my feet for attention, I am going for a swim in an iron swimsuit. It also forced me to reflect on my current pace of penciling, and whether it’s time to accept some of my limitations and just make some damned art in spite of them. This heightened sense of time also made me realize how much time I spend on every page trying to decide whether to erase something that I am very aware is inadequate.

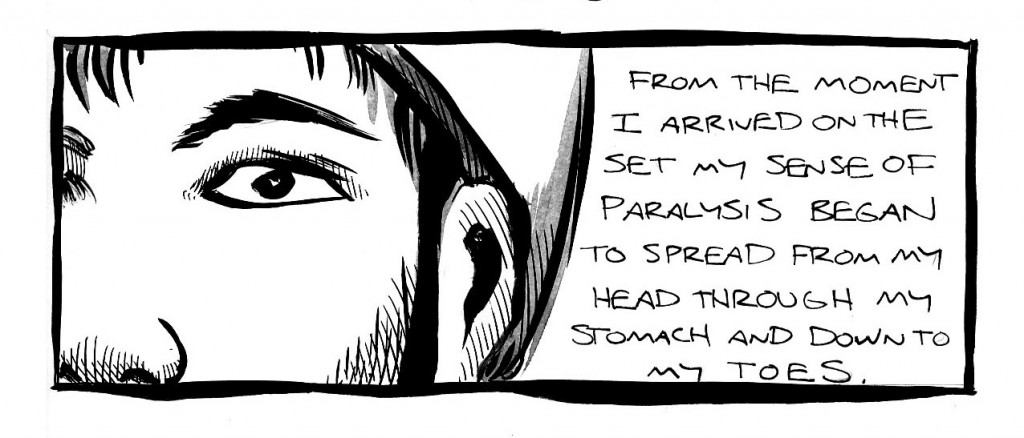

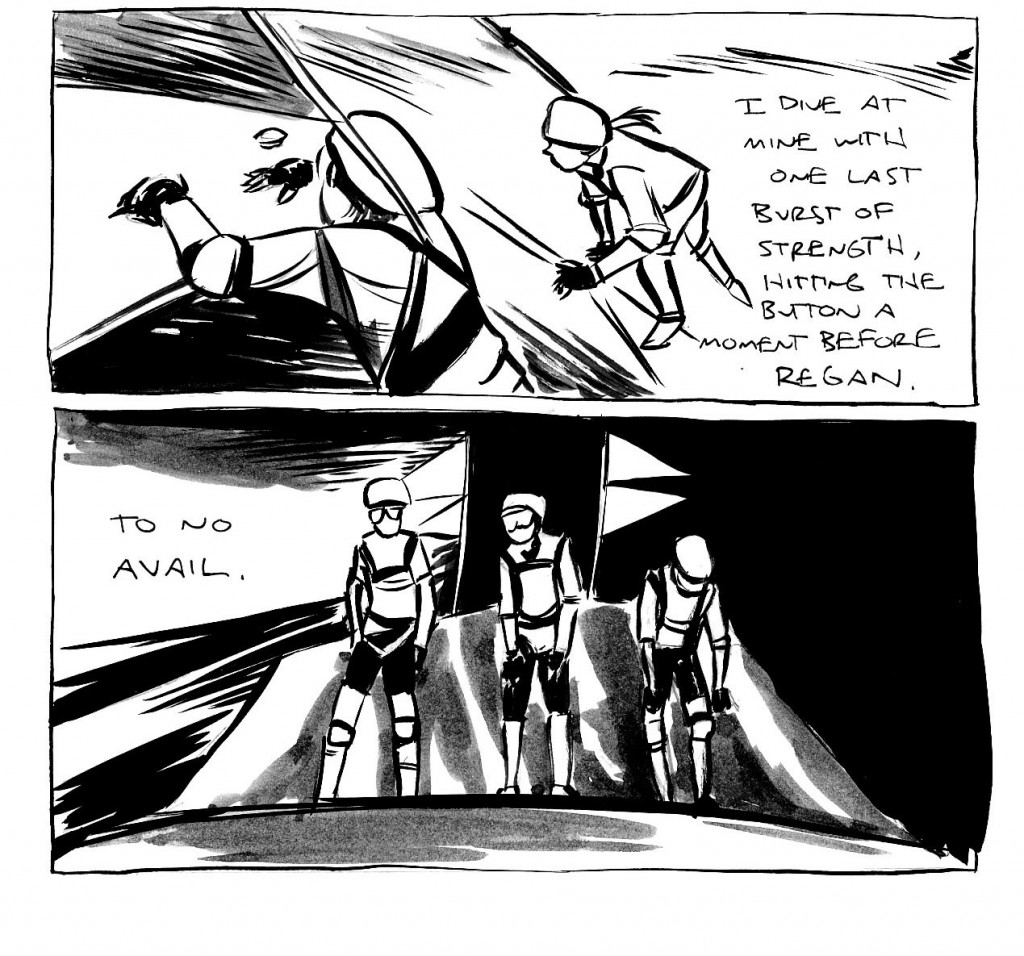

For the majority of the twenty four hour period the room seemed still, but not calm. Besides brief periods of sociability (the arrival of pizza or frozen deserts), the only sound in the room was the sound of scribbling, and the ubiquitous CD player, spinning out a long set of David Bowie, Iggy Pop, Belle and Sebastian, Bjork and Miles Davis. Each person seemed to have approached the challenge differently- Marc Palm and Henry Chamberlain came in with several pages of roughs, Eroyn Franklin had a stack of photographs and a rough concept, and pretty much everyone had some type of visual information they could use to prime their imaginations in a pinch. Having made a completely improvised and nonsensical twenty four hour comic in the past, I was determined this time to emerge with a coherent story, and so I brought with me a well-honed anecdote and a stack of reference material.

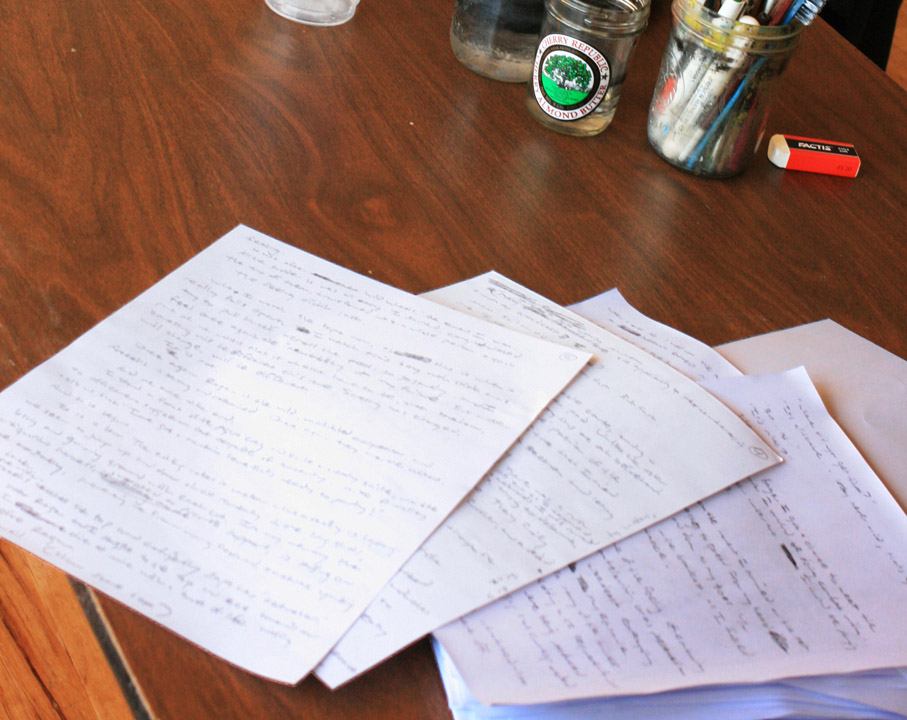

As I knew it would end up being a fairly wordy comic, I started with a script, writing out six and a half pages by hand in about two and a half hourse. Although the chunk of time right off of the top hurt my morale initially, it was what ultimately enabled me to have a coherent story from start to finish. After sorting through my reference, I then proceeded to pencil the whole thing, inking the lettering in as I went to save time. By the time I had penciled the whole book I had a burst of energy from the pleasure of switching tasks to the finishing. I worked in reverse order for the inking, starting from the back, so as to avoid the dreaded, almost inevitable, visual decline- I rationalized that the drawing was probably more solid on the earlier pages, and could therefore hold up to some sloppier inking.

And several hours after the sun came up, about twenty-two hours in, I was done. And most importantly for me, I had managed to produce a coherent, self-contained story in a single sitting.

The Morning After

It is beautiful to create.

-Akira Kurosawa

When you’ve finally slept, stumbled through the next day and the one after that and finally managed to realign your sleep to that animal pulse, what’s left of the experience? For me it’s the thrill of making, the reality of a stack of blank paper transformed into a readable story in the course of a single rotation of the earth. No matter what art form you work in, that speed of gratification, that narrow distance between conception and execution, is a rare thing. It can also serve as a reminder of how much of our activity through our days is unfocused, or even unintentional, and periods of this heightened awareness of self can lead, in my estimation, anyway, to a long-term adjustment of the intentionality of your action.

Or it could give you a headache, make your neck and shoulders sore, and cause you to be cranky to everybody at your office come Monday morning.

(If you end up with that stack of papers, you’ll still think it was worth it.)

Further information-

-Scott McCloud’s 24 hour comics page

-the book “24 Hour Comics”, which includes David Lasky‘s story, “Minutae”, and other excellent stories by K. Thor Jensen, Paul Winkler and others

-Dave Sim’s 2HC “Bigger, Blacker Kiss” in digital form or in print

-more photos of the 2010 Seattle 24HC event, and video interviews of comically weary cartoonists

-my secondary school cartooning idol Jared Hodges has many books and a process blog

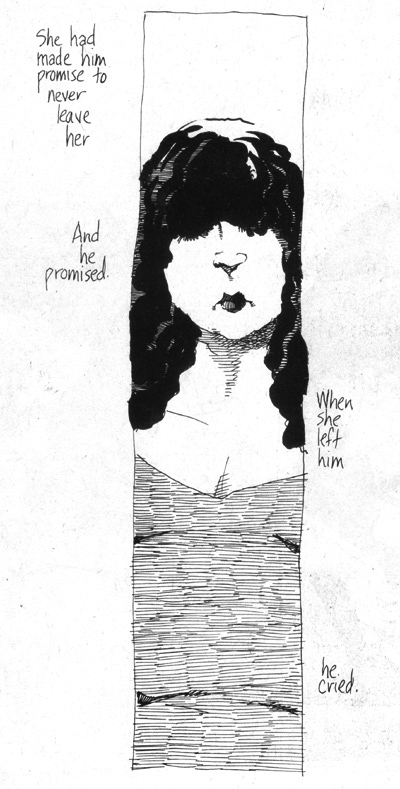

-you can read my complete 24 hour comic, “Guts,” here

Hey Sean. The ninjas look great! Can’t go wrong with ninjas….

Blogging has some of the unstoppering characteristics of the 24 hour comic day, I think. Certainly since I started blogging a few years back I write, much, much faster. (Not that everyone thinks that’s a good thing!)

Noah- Well, here’s hoping some of your speed rubs off on me. There’s something very wrong when I spend hours fretting and futzing and fiddling over a post that’s primarily about learning to let go and knowing when to stop fretting and futzing and fiddling!

Blogging and 24HCs have another thing in common with each other- the audience will approach them differently than they might another work in the same medium. “That’s really some fine writing- especially for a blog”- essentially making some type of allowance for all of the attendant assumptions that travel with the label of blog, or improvisational 24 HC, or whatever. In fact, it’s not dissimilar to the way a person reacts to a piece of writing that’s non-fiction- a completely different set of expectations come to bear on their experience with the material.

As far as ninjas… well, what can I say? We were the perfect age to catch the ninja craze in its second wave, around 1987ish.

I’ve got to try a 24C someday…maybe organise one in the Paris area…

Pingback: Scott McCloud | Journal » Archive » The Day in Review

What I like about this and Sean’s previous post is that they’re grounded in actual experience; they’re thorough and informative; and he has a sense of humor about himself.

More, please!

Thanks for the kind words, Alex! I’m going to try to back off on the personal biography aspect in my next few posts, but I’ll do my best to keep the ground-level, in-the-trenches perspective intact.

While I’m going to dive right into personal biography in my next post!

Looking forward to it :) I don’t have any problem with autobiography, I just want to avoid my possible excesses, and try to steer away from that being the formula or lens by which I view each topic.

Also, you should really organize a 24C event- like other indoor sports, it’s a lot more fun if you do it with other people. Make sure to have a comfortable room, and that everyone has music veto privileges. :)

As a long-time Nanoer, I am thrilled to see that comics has their own version. It’s so cool!!

I wish we had one around here. It sounds like so much fun. Or possibly I will just have to arm wrestle my friends into making one, lunch table circle style… I could draw the horses, Alura could draw the ninjas, hhhmmmm.

Still have lots of inking on ‘Both Worlds’ to do, I put it away for about a week before looking at it again, and I’m really happy with it… This event always gives a proper shake up to those projects in slumber. It was great to meet you, this is a wonderful reflection you wrote.

Pingback: GUTS: A Young Adult Television Fiasco - Living the Line