The comics blogosphere and comics academia can seem both unaware and mistrustful of each other. This is the case despite the fact that there are many people who work in both worlds. Probably it has something to do with the fact that traditional publishers are understandably wary of making their texts accessible online; probably it has something to do with a fan culture’s understandable skepticism of the ivory tower.

In any case, I thought it would be nice to buck the trend at least a little by devoting a roundtable to an academic work. After some discussion, we decided to read Charles Hatfield’s Alternative Comics: An Emerging Literature, one of the most respected academic publications on comics of the last decade. The choice seemed especially pertinent since Charles is a blogger as well as an academic; he writes with Craig Fischer at the wonderful Thought Balloonists. (And Charles has graciously agreed to weigh in himself at the end of the roundtable.)

__________________

Alternative Comics turns out to be an excellent book to bridge the comics/blog gap in that its concerns, interests, and enthusiasms are ones which map closely onto the online world (or at least the art comix parts of it). Specifically, the book focuses on history, on formal elements, and on authenticity, especially as the last relates to autobiographical comics. Alternative Comics also, and somewhat to my surprise, engages in a good bit of advocacy — Charles definitely sees himself as validating comics as art and (more specifically) as literature for an academic audience.

The part of Charles’ discussion I found most compelling was the formal. Charles sees comics as “An Art of Tensions,” defined by how it negotiates between competing ways of making meaning: image vs. text, single image vs. image in series, seriality vs. synchronism, sequence vs. surface, and text as experience vs. text as object (loosely narrative vs. style.) Most of these contrasts will be familiar to comics readers, but Charles’ exposition of them is unusually clear, and his application to particular cases is very nicely handled. For instance, here’s a discussion of seriality vs. synchornism (events happening one after the other vs. events happening at the same time) in a page from Mary Fleener’s “Rock Bottom”:

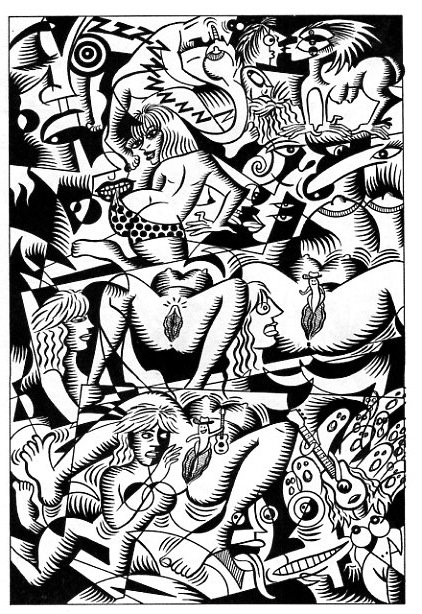

For instance, the climactic full-page image from Mary Fleener’s autobiographical “Rock Bottom” depicts what appears to be (the story equivocates, forcing the reader to suspend judgment) a drug-addled sexual imbroglio between Mary, her occasional lover Face, and a glamorous woman named Roxanne. Fleener’s trademark “cubismo” style, a dizzying blend of Picasso and her own sharp-edged technique, offers a radically disorienting minefield of interpretive choices for the reader, as figures blend in a sexually suggestive synchrony. Is this a dream, as Mary’s sleepy expression on the top left implies?…The overlapping images imply an entire sequence of activities that Mary cannot remember upon waking the next morning…. Fleener uses a single composition to suggest successive stages of action.

(page 55)

Such formal exegesis points, for Charles, to the complexity of the task of creating comics and to the complexity of reading them. For Charles, comics require formal choices from creators and interpretation from readers. “Comics demand a different order of literacy: they are never transparent, but beckon their readers in specific, often complex ways, by generating tension among their formal elements.” (page 67) Comics are not, as they have often been accused of being, simple or easy — they require complicated parsing, and such parsing “is a must, not only for the discussion of comics as literature but also for sociological and ideological analysis of comics.” In short, to understand comics requires expertise — a move which neatly validates comics as aesthetic object while simultaneously establishing the necessity for academic interpreters.

Thus far I don’t have any particular objection. I agree that comics have complicated formal elements (as complicated as any other art form, certainly); I agree that taking those elements into account is useful for criticism (maybe not “a must” in every case, but I don’t need to quibble); and I agree with the implied conclusion that the academy and comics would both benefit from academic appraisals of comics.

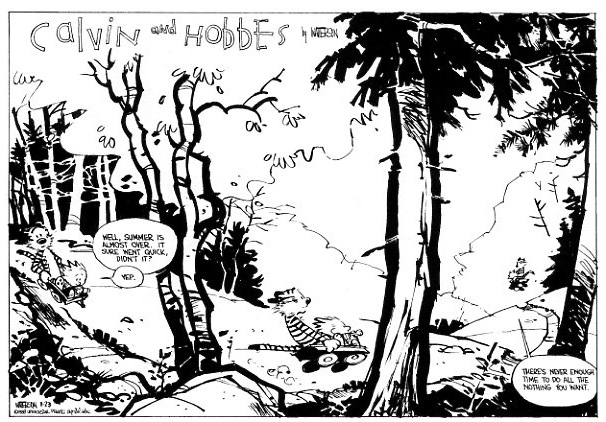

So I can see the strategic and critical benefits of Charles’ central focus on formal considerations. Unfortunately, from my perspective at least, there are downsides as well. Those downsides being that Charles often seems so excited by formal elements that he fails to notice when the content is maybe not all that. Here’s an example from Bill Watterson’s Calvin and Hobbes:

Charles points out the formal mastery of this image:

Both the word balloons and the tree trunks in the foreground (which serve as de facto panel borders) parse this scene into successive moments, introducing the time element, yet the unbroken background blurs our sense of time, conveying at once the characters’ deep immersion in the scene of natural beauty, and the headlong urgency of their ride….

Which is all well and good, but it’s hard for me to appreciate the drawing with the huge wads of saccharine glop in my eyes. (They burn! They burn!) Really, this is barely above hallmark card sentimentality, with the romanticized child always already giving voice to the cartoonist/reader’s adult nostalgia. The synchronism, too, is a function of the nostalgia; the characters rolling through a timeless frozen present on their way to a timeless frozen past, all against the sketchy trees evoking a landscape of blurry but beautiful memory. It’s a banal, sepia-toned piece of wannabe-profundity; the sort of Zen and the Art of Childhood nonsense that Charles Schulz wouldn’t be caught dead promulgating.

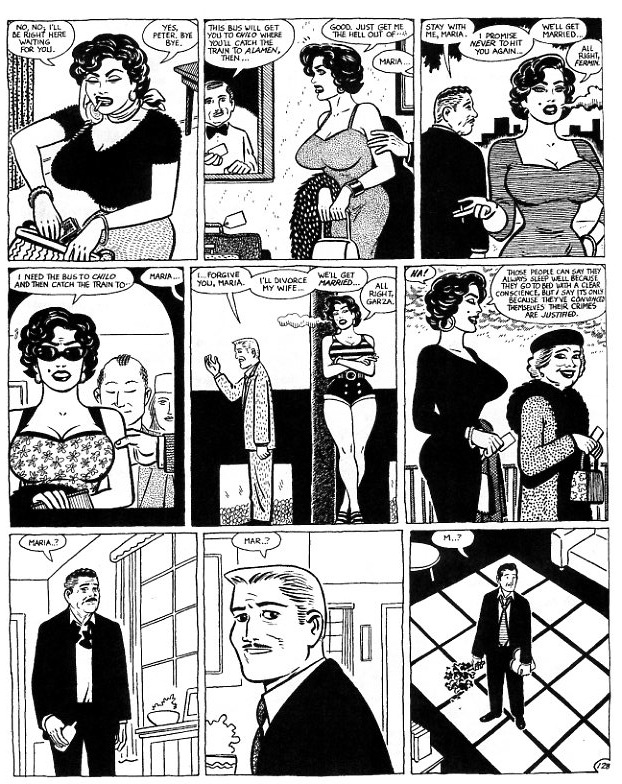

Here’s another example, a page focusing on Maria, one of the central characters in Gilbert Hernandez’s graphic novel Poison River:

Charles has a lengthy analysis of this:

What is notable here is not Maria’s character per se, but the way her seeming absence of character, her stereotypic perfection and consequent emptiness, make her the perfect magnet for the desires of the three men, each of whom longs for affirmation from Maria but of course cannot trust her. That Maria embodies a stereotype of feminine affectation and charm is precisely the point: though she remains inconstant, unpredictable, and thoroughly amoral, her continual costume changes and affected good looks make her a perfect vehicle for the men’s desires…Maria’s story becomes the men’s story, a story in which all of the relationships follow a predictably dysfunctional pattern. The men change, and her costume changes, but the overall pattern stays the same.

Nowhere is this more evident than in a one-page, nine-panel sequence…in which Maria attempts to end her relationships with the three men by running away. As she tries, repeatedly, to leave by bus, she is stopped by men who want to marry her, take care of her, and make her stay. The same scene repeats itself, with variations, several times. Maria wears different clothes in each of the first six panels, and in the odd-numbered panels…talks to Peter, Fermin, and Garza respectively. Thus we know that this sequence covers a significant span of time, and a number of discrete incidents in her life. Yet the movement between these panels is deceptively easy: the flow of dialogue and action implies continuous movement within a single scene. A hand reaching for Maria in panel two leads easily to Fermin’s dialogue in panel three, though the two panels depict two different incidents (as signaled by Maria’s change of clothes.) A similar confusion occurs between panels four and five: again, a hand reaches for Maria, leading to Garza’s placatory speech in the next panel, but again Maria’s appearance changes between the two images. By thus blurring our sense of time, Hernandez suggests a pattern of repeated behavior. The dialogue and actions suggest a seamless sequence, yet the shifting costumes and rotating male characters point out the passage of a great deal of time.

This page depicts separate incidents from Maria’s life, yet verbal echoes suggest that these incidents all follow logically from a pattern of dysfunctional relations with men. In panel two, the ticket seller tells Maria that her bus will take her to Chilo to catch a train; in panel four Maria attempts to purchase a ticket to Chilo for the same purpose. In each case someone off-panel calls her name and reaches out for her. In panels three and five, lovers try to keep Maria by promising marriage, and in both she responds, “All right….” On the bottom tier of the page…Fermin, Garza and Peter share the same fate, loss of Maria, and all three call out for her in vain. Each man appears different, yet each calls for her in a questioning tone, revealing his surprise and aloneness as she finally escapes from him. These last three panels suggest a gradual loss of hope, as Maria’s lovers seem to lose the power to speak: we go from Fermin’s “Maria..?” to Garza’s “Mar..?” to finally Peter’s hopeless, inarticulare “M..?” The interplay of word and image links these separate instances within a consistent behavioral pattern and provides a sense of direction to what would otherwise be a radically disjointed sequence. Though time leaps forward with dizzying speed, via uncued scenic transitions, repetitions in both dialogue and composition ease the image/series tension and allow us to see these drastic shifts as part of a predictable, indeed inevitable process.

I’ve quoted this entire passage because it’s such a good example of the virtuoso way in which Charles manages to link his formal interests with thematic ones; Hernandez’s manipulation of sequence and time are here seen not just as tricks, but as the actual subject of the page. Repetitive but disjointed images signal a compulsive repetition of desire and finally of loss.

The analysis is also, to me at least, an example of the way in which an eagerness to appreciate formal virtues leads Charles to gloss over some possibly sticky issues of content. “What is notable here,” Charles says, “is not Maria’s character per se, but the way her seeming absence of character, her stereotypic perfection and consequent emptiness, make her the perfect magnet for the desires of the three men.” I see Charles’ point in terms of the formal arrangement of this page, certainly; Maria is a cipher moved from hand to hand and from panel to panel, the very repetition of her actions over time emptying out her individuality — she seems more like a mechanical dress-up doll than a person. Even her vacuous cynicism in the sixth panel seems rote; isolated in time it comes out of nowhere and goes into nowhere, a brittle façade emphasized by her solid black dress. She’s a noir silhouette, all curves and no heart.

But if Maria’s absence is “What is notable,” you have to ask, notable to whom? To the men who desire her obviously — but who are those men? Peter, Fermin, Garza, yes — but Peter, Fermin and Garza aren’t present in panel 6. The page is divided into three tiers of three, but that grid forms a single unity, and if that unity is not the absent Maria, then what is it?

The answer seems simple enough; it’s Hernandez himself. If Maria is a doll, it’s Hernandez who made her; it’s he who poured her into those bombastic proportions and then into those boldly-patterned clothes. It’s Hernandez who decided to make Maria a Dan DeCarlo pin-up, and then decided to make this page a fashion spread. She’s his Barbie, and much of the pleasure of this sequence, for both him and the readers, must be precisely the erotic montage; the excitement of seeing that form manipulated, thrown out of sequence and out of her clothes, as her life-in-time is chopped up into consumable images of those giant breasts, which are always front and center. In this reading, the distraught men in the bottom panel can be seen as, simultaneously, a hypocritical expression of guilt; a noirish masochistic thrill (emphasized by that very filmic final black and white patterned panel at the end); and a victorious crushing of the competition. Maria’s desirability is validated by the many men who want her, and her availability is confirmed by their failure. Only the creator/reader truly has her in all her surface voluptuousness — a surface which is, of course, all there is to her. In its insistent formalism, the page makes of Maria a form that can be possessed, both by her creator and by those who appreciate his skill.

I haven’t actually read Poison River, but other pages Charles reproduces, and the bits I’ve seen of Hernandez’s other work (I believe I read Heartbreak Soup once upon a time) don’t lead me to think this reading is out of bounds. Hernandez’s portrayal of female bodies is insistently fetishistic, and that fetishism seems only fitfully integrated into his often-stressed concern for women. In terms of his female characters, he eroticizes stereotypes at the same time as he critiques them, and the results, to me, often seem callous or banal rather than insightful. At the least, I think any reading of this page should confront more directly than Charles does the debt to pin-up art and the problems that suggests.

I think Charles doesn’t do that for a couple of related reasons. First, he’s more inclined to see comics history as a resource rather than a hindrance — as, for instance, in his thoughtful (if not entirely convincing to me) defense of the iconic use of funny animals in Maus. And second, as I’ve said, he sees formal complexity as the central aesthetic achievement of comics. Gilbert’s mastery of the comics medium is a seduction Charles has little interest in resisting.

These particular predilections — an enthusiasm for comics history, an enthusiasm for comics form — aren’t ones I share, which may be why I’m impervious to the charms of much of what most people consider to be the comics canon. Indeed, of all the comics Charles discusses — from Harvey Pekar to Crumb to Spiegelman — I pretty much actively dislike all of them. Still, Charles’ book helped me understand better why I dislike them. Or to put it another way, even when I disagree with it, Alternative Comics is a fun book to argue with.

___________

Update: The whole Blog vs. Professor roundtable on Charles Hatfield’s Alternative Comics is here.

Maria is Luba’s mother—a much fetishized (by character and author) woman…but also a very complex one–and one who is explicitly and clearly not as vacuous as her mother appears. Maria uses her body to her advantage—and men in the book even discuss how “there must be something underneath that beautiful exterior” (paraphrasing)–but they can’t seem to locate it or figure out what it is. The book, though, is really Luba’s “origin story”–and (as in the rest of the Palomar stories), she is a complicated, intelligent, independent (and, yes, nearly nymphomaniacal) woman. There is some indication that Maria too is more complex than she appears—although her abandonment of Luba and neglect of her other daughters makes her somewhat hard to sympathize with. Point being…yes…Maria is meant to be seen as empty, vacuous, beautiful, etc. (and ends up being fetishized)…but the book does examine/critique the men in the story who treat her this way (even if Gilbert does so himself in his depiction at times). The counterpoint of her daughter, Luba, also complicates matters. Hatfield seems well aware of some of these things in the book–even if, as you say, the focus is often more on the how the form of the book (and others he discusses) links to and reflects the content. Maybe more focus on the politics of the book in terms of gender would make some readers happier…but, to my mind, anyway, there is an enlightening/interesting discussion of race and nationality in Hatfield’s book–particularly as it relates to Palomar/Latin America’s relationship to the gangster Los Angeles portrayed in Poison River. Some of the things Hatfield discusses in this regard can actually be compared to and laid onto/across/against Poison River’s gender politics.

I kind of wanted a more in-depth discussion of the hermaphrodite fetish that Peter Rio has–but maybe that will all come out in the rest of the roundtable.

Anyway, Hatfield’s book is a really good one. That’s pretty rare in academic books (or any books really)… The Hernandez section is the best part, to my mind.

You should change your tag though: Altenrative

Happy Birthday, too…

I thought Charles’ book was good too! I think I said that….

I guess a point I’m trying to make isn’t exactly that Charles is ignoring form for content, but rather that complexities of form can tie into content in ways that may not necessarily be ideal. I think both Watterson and Hernandez use form in effective ways — but it doesn’t necessarily follow that that effect is positive.

I think Charles is very aware of the fetishization of Maria. I don’t think he’s as aware of the way in which that fetishization is perpetuated on the formal level of the book itself, and how that really calls into question whether the fetishization is in fact a critique or whether it’s just what it is. I mean, that page above with the insistence on chopping up time and the fetishization of the breasts — it seems like textbook Laura Mulvey, doesn’t it?

Noah,

As someone who appreciates your voice despite disagreeing with at least half your opinions, who delights in the fact that you’re the kind of guy who would try to skewer Watterson for nostalgia despite my love for Calvin and Hobbes, who thinks there probably is an important discussion to be had about the portrayal of women in Gilbert Hernandez comics, I feel compelled to say that lines like this:

“I haven’t actually read Poison River, but other pages Charles reproduces, and the bits I’ve seen of Hernandez’s other work (I believe I read Heartbreak Soup once upon a time)”

make you sound like a goddamn fool.

Far be it from me to tell you what to write. There are interesting observations that can come from interpreting a page of comics out of context. But if you’re going to offer up potential summary readings of an artist and one of his most significant works, is it really too much to ask that you fucking read it first?

The above offered up with affection. Truly.

Yeah, I get this a fair bit.

There’s this thing where people feel you need to read a significant amount of an artist’s work to comment on some small portion of it. Generally it only holds when the artist is supposed to be important; I mean, I think most people would be happy to dismiss most stupid super-hero comics after looking at a page or two, right?

The thing is, if you insist on only having conversations with people who have read a significant portion of an artists’ oeuvre, you’re only going to have conversations with people who like the artist enough to read a significant portion of the artist’s oeuvre. I don’t like Gilbert’s work that much. I’ve read various stories and a book, and I find it mostly boring and obvious. As a result, I don’t really want to read much more of it.

So, yeah, it is too much to ask. There are lots of great things to read. Why should I bother with something that irritates and bores me? I mean, Charles spent a lot of time telling me how much I should like Hernandez…and everything he said, and all the examples he provided, just confirmed me in the strong sense that it is not for me.

I can explain why I don’t like it from what I’ve seen — which is what I do here. This page gets at some of the things I don’t enjoy about his work — namely, his fairly predictable fetishization of women. I don’t see why I shouldn’t be able to talk about that, especially when I explain where I’m coming from and why.

I actually had a really fun conversation with my friend Bert Stabler recently about I Spit On Your Grave, a favorite movie of mine, which he slanged…even though at the time of our conversation, he hadn’t seen it. I guess my response should have been to ball him our for his lack of seriousness…but, you know, instead I just enjoyed figuring out where he was coming from and why (though I encouraged him to see it…because it’s great!)

Comics folks, though, get really exercised about this sort of thing; as if expressing an opinion without having read all the requisite documents and their cousins is somehow a moral failing or a betrayal. I think it’s probably the subculture thing — the idea that you need to have learned the secret handshake to participate in the conversation. I think that attitude is poisonous, personally. It’s not a game I’m going to play.

Oh…and it’s nice to see you again, Jason. I haven’t seen you comment in a while!

you should probably read at least poison river if you’re going to make comments like this. not because “you need to fully appreciate beto’s genius before you say anything bad about him” or anything like that, but just because one page ripped out of context only tells you so much. there’s a lot of stuff going on with these characters that informs a page like this and at least mitigates some of the things you find creepy. not saying that you need to immerse yourself in something you already know you don’t like just to be really sure, just that to call something out for being objectionable based on one page isn’t really a great look.

But can’t the page itself be objectionable?

I’m actually aware from Charles’ discussion that the fetishization is dealt with to some extent. And I don’t think I’m claiming it’s the most sexist thing I’ve ever seen or anything like that. But the page uses formal elements to fetishize the female character. It’s not even especially subtle. I think it’s worth pointing that out…and worth noting that in the other works by Gilbert that I’ve seen, this is an issue as well.

I mean, the question for me is, if the point here is to critique the fetishization, why is that fetishization reproduced on a formal level for the pleasure of the viewer? Why use pin-up tropes at all? Nothing Charles said in his extensive analysis of this book, and nothing I’ve seen in my reading of other Gilbert works (Including at least one complete book) suggests that there’s a good answer to that question.

It’s funny…I think this is also actually a difference between the blogosphere and academia. If I were an academic, obviously I’d have read everything there is to read about the Hernandez brothers before venturing into print. Which is a great thing about academia, and one of the reasons academics can be fun to read. But blogs are more about jumping in without covering your ass — and I think that can be worthwhile as well. Though obviously others may disagree!

sorry if i appear dense, but just who is pretending that gilbert hernandez’s work somehow serves as a “critique of fetishization”? you, noah? or charles? i’m confused, partly because of how absurd that theory sounds if it’s to be taken as the end work on hernandez’s discourse. kind of like saying marston was strictly feminist & ending it there.

the book looks interesting, anyway. i’ll try to get it somehow.

“as the end work” should read as “as the end worD”. sorry.

It’s available on Amazon for $15.

I think the long passage I quote from the book suggests that Charles believes Hernandez is critiquing the fetishization/objectification of Maria and of women in general.

I’m interested in the parallel with Marston. I can see where that’s going to some extent, though the masochism/feminism bit seems a lot less weird, and less fully thought through, in Hernandez than in Marston. Do you disagree? I’d be curious to hear how you think Hernandez’s feminism works with his fetishization. I’d be a lot more interested in him if I could be convinced that there was a meaningful connection there.

well, for starters let’s assume both marston & hernandez are “feminists”. i’ll put the word in quotes because a man’s feminism (including my own) will always be a compromised beast.

my comparison between hernandez & marston was very broad. if we get any further we’ll mostly find differences, of course. for starters the “feminism” is not the same in both authors. marston’s is highly theorized from the outset. hernandez’s seems more intuitive. you are right to say it’s not “fully thought through” when in fact it probably isn’t at all.

but then is the thinking through of any relevance? the “critique” part in hernandez is never fundamental, it’s a byproduct of the story & the drawing, if you will (you’d probably find this out by yourself if you actually read the books). to take a relatively superficial example: hernandez likes to draw women of various shapes & sizes, which he imbues with an explicit potential of attraction, i.e. you are expected to desire those women characters. the reader can see this as a criticism of hegemonic constraints on what constitutes an “attractive woman” — but in fact there is no criticism of that sort. what it is, at most, is a work ethic in the shape of an aesthetic (or the other way around). the criticism part is entirely constructed by the reader, not the author.

yet (keeping with my simple example) the reader can also see the conflict between the objectification (those women are treated as objects of desire) & what i would call (in purely technical terms) a tenderness towards his female characters. the women are attractive but they are different from one another. they are not all one & the same: you can’t just objectify one idealized “woman” among many who just can’t cut it, you have to love all of them, warts & all. & this, you will find, explicitly, in hernandez. & this can also be construed as a criticism, for instance, of women in superheroes, which are all more or less built on the same frame. it’s a valid way to interpret hernandez but it’s not what hernandez is explicitly saying: he is telling a story.

& thus we can get back to marston, to whom women were superior just for the fact of being women, which we can take to mean: because they all enticed his desire, not just that one model that everyone sees in the movies & the magazines but also this other more bulky shape, & even that chubby girl who eats all the time: a socialism of desire, if you will. from that point of view i’d be tempted to say that both gilbert & jaime went far beyond marston. but maybe that’s where you thought that was going?

damn, my last comment was quite jumbled & even redundant in parts. hope you can wring some meaning out of it. that’s what you get for thinking in french & then writing in english.

More than any comic I’ve ever read, context is everything in “Poison River”. Criticizing single page out of context from Beto’s longest and most complex work isn’t going to be very fruitful, I think—and will be especially unconvincing to those who have actually read the work. Something along the line of taking the multi-page throwing-back-and-forth of insults between the two whores in John Barth’s The Sotweed Factor and criticizing Barth’s oeuvre for being nothing more than a bunch of filthy lists.

oh, & noah, about talking about books you haven’t read, i suppose you haven’t read pierre bayard either? really, you should!

I think criticizing the sotweed factor for being the prurient ramblings of an dirty adolescent is actually fairly on target. (And I like the Sotweed Factor!)

I’d be somewhat more convinced that I’d done horrible violence to the work if anyone had yet brought up a really convincing argument as to why I’m wrong. Perhaps Charles will do so at the end of the roundtable.

David, I think that’s an interesting take. I guess I would argue a couple of points.

First, I think Charles makes a pretty good case that Hernandez is a conscious artist, who is not just “telling a story.” The fact that he fragments narrative so assiduously suggests that beginning/middle/end is not what he sees as his most important goal. The cultural/capitalist critiques seem very obvious, as do the comments on art and artistic creation. Indeed, most of these seem too obvious for me; I find them tiresomely familiar (but that’s maybe another argument.) I mean, obviously the story is important, but from the Hernandez I’ve read (which includes a number of stories as well as Heartbreak Soup), and from Charles’ extensive discussion, he just doesn’t strike me as an especially pulpy or unconscious artist in general. I mean, he’s not Bob Haney or even John Ford. He sees himself, and comes across as seeing himself, as a serious artist.

Second…your defense of his use of fetishization is more or less how I’d defend it. Being willing to fetishize different body types is a pretty low bar…but it’s a bar that much of comics, not to mention the rest of the culture, often fails to hurdle, and I’m willing to give him credit for it. And he’s obviously very interested in female characters, which again I appreciate. But..I still don’t see anything that gets around the Laura Mulvey critique of the gaze; his work is really organized for the benefit of male visual pleasure and fetishization in a way that undermines the tenderness you discuss, as well as the critique which Charles finds in the page above.

Again, it’s not that the critique isn’t present, but that the visual style and the formal choices seem to work against it rather than with it.

Marston doesn’t provide as wide a range of female bodies, certainly. I’d say, though, that his use of fetishization is much more directly and explicitly linked with his feminism. For Marston, fetishizing strong women is part of men learning to subjugate themselves to women and of women learning to subjugate themselves to women, for that matter. The viewer/audience in Marston is always both male and female; the fetishizeris always supposed to both be the possessor and the possessed. I don’t see that happening in this Hernandez page; the possessor is emphatically male, and the visual referents (to pin up art and pulp noir) puts the viewer just as emphatically in the male position (as opposed to Marston, where the visual referents are to doll stories and feminized frilly children’s lit.)

which is why i pointed out that we’ll see many differences between marston & hernandez beyond the superficial similarities. my example on the various types of bodies is just that, one example. but it’s symptomatic of the multiplicity of points of views in gilbert hernandez. you might say that every character is potentially one gaze among many.

as for the page you quote & which informs much of your thesis, well, as others have said, it’s just one page among many. you’ll find other pages whose visuals read like archie comics, which is not specifically male-centric literature. & elsewhere, you’ll find narratives that read like fotonovelas, which is not particularly male-centric either.

which brings us back to the “serious artist” part. i’ll admit i overstated my case of hernandez not thinking about the undertext & just telling his story. but the fact remains that his stories are what’s front & center. hernandez strikes me as someone who has so much to tell he has to put as much narrative content in every panel as possible. look at the page you quoted, how it’s structured around a story, with easily recognizable (pulp) visual cues. that page oozes with narrative. the rhetorical/dialectical content is precisely what’s not on the page. & if it’s not on the page then where is it, if not in the reader or the critic’s eye?

also–to be honest, i can’t follow you very far in your criticism of the male gaze. frankly, i don’t care. if (& only if) hernandez’s whole work took the form of the twisted discourse about male visual pleasure which you seem to be describing, & particularly if that was all there was in his work, then OK, it would be fair game indeed to criticize it. but i don’t see such a one-sided overarching discourse in his work: if anything i read a conflicted, contradictory discourse that doesn’t really resolve itself into a neat coherent whole, no matter the “consciousness” on display. & of course, saying this, i’m not really saying much.

Of course meaning is a negotiation (or a conversation) between the text and the reader. But it seems like one thing Charles is saying is that that conversation has to be on the page; it’s a conversation which takes place through (and is therefore in large part about) the formal structure of the page(s). If the pages ooze with narrative, you have to see that on the pages themselves (which I think Charles does, actually.)

“if (& only if) hernandez’s whole work took the form of the twisted discourse about male visual pleasure which you seem to be describing,”

I don’t really get this. First, I don’t think the male gaze I’m describing is particularly twisted; it’s pretty straightforward, actually (in various senses.) And I don’t see either why it’s wrong to point it out or think about it as an element in the work. I of course wouldn’t say that it’s all there is to Hernandez’s art…but it does seem to be a fairly important element. It’s something that strikes me whenever I read him, anyway; I don’t see why it’s invalid to bring that up.

“i read a conflicted, contradictory discourse that doesn’t really resolve itself into a neat coherent whole”

Do you mean this for Poison River specifically? Or for his work as a whole? Charles’ reading seems to feel the work is more unified than this suggests I think, unless I’m reading him wrong….

“you might say that every character is potentially one gaze among many.”

I’d be interested to see this thought through. It’s really not my impression of his work; while narrative is fractured and split, perception and style don’t seem to vary that radically (at least not in the parts of Palomar I’ve seen — I know he’s done more experimental work as well.)

I hope it’s just a matter of the point going over your head—or are you actually suggesting that, because you found (the irrelevant specific example of) the Sotweed Factor to be “the prurient ramblings of an dirty adolescent” that it somehow “proves” that you could have come to that conclusion from a few stray pages? And therefore you could do this more or less infallibly with any book (thus justifying your criticism of Poison River)?Because if that’s not your point, then what was?If not, then surely you could have used your imagination to come up with another example.As for “proving how [you’re] wrong” (an odd stance, as you haven’t proved how you’re right)—well, a number of people have suggested you actually read the book. I was put off of Beto’s work for years because my first exposure to it was a random chapter of Poison River in L&R. I couldn’t make heads or tales of it—all I got out of it was “Chicks with Dicks”. Years later I read my way through the earlier Palomar stories and eventually read through the Poison River collection. It’s now one of my favourite comics by far. I sure don’t jerk off to the book, so there must be something else that keeps me coming back other than the women.

I think Beto is great — but he sure likes drawing women with big tits.

Like, Russ Meyer big.

To such an extent that a good deal of his work is, well, problematic. Not, say, Cerebus-problematic or even R. Crumb-problematic, but still…troubling…for a reader with a minimal degree of gender consciousness.

And does ‘problematic’ automatically make for lesser art?

Noah, your critical stance in general seems very ideologically determined, which I guess is fine, but which also shortchanges a lot of interesting art.

Hey Andrew. My point was that it’s possible to have insights about a book, even a complicated book, based on a relatively small sample.

I didn’t say anything about “infallibly” ever, I don’t think. But…so far you’ve said, basically, “I like this!” and “I don’t jerk off to it!” I don’t find either of those arguments especially persuasive or interesting.

And of course no one can prove they’re wrong or right about this stuff; I was indulging in a modicum of hyperbole. You can explain where you’re coming from and why, though. Or you can just snark. The latter being kind of what the internet is for, I guess.

Hey Jones! Yeah, I’d say obviously Crumb has more problems, as does Cerebus…though you could say both of those artists are more consistent as well, in that they don’t make much pretense to caring about women, particularly….

So Gilbert just pretends? If so, he’s a pretty damn convincing phony.

“you might say that every character is potentially one gaze among many.”

I’d be interested to see this thought through. It’s really not my impression of his work; while narrative is fractured and split, perception and style don’t seem to vary that radically (at least not in the parts of Palomar I’ve seen

well, that would require an essay on its own. & at this point in the day i don’t have much time.

but again: palomar is a long work. there’s far-reaching effects that you won’t get in a cursory glance. your comments continuously read to me like “duh, that proust guy is basically just this one guy rambling about cookies, innit?” (yes, that’s a caricature, if you ask.)

Hey David. There’s no rush! And I certainly understand that there are complex effects in the book. But I’ve yet to hear anything from you, from Charles, or from anyone else that confronts the way those complex effects do or do not deal with the compulsive fetishization of women, or with the way that the narrative disjunction appears to feed into that fetishization.

Matthias, “pretense” doesn’t necessarily mean “pretend”. I don’t doubt Gilbert’s sincerity or interest.

I agree in general that there is a “pleasure of the male gaze” element in the book…On the other hand…there’s a heavy emphasis and depiction of male homosexual sex in beto’s work—hardly what the typical straight male reader is looking for. Likewise, the hermaphrodite strip club seems to first invite the “male gaze” and then frustrate it—in “Crying Game” fashion.

The hermaphrodite thing is a fetish for one of the characters—but it works against seeing the entirety of the work as merely “pleasure for the male gaze.” There is, in fact, effort to invite the objectification of women as sexual objects—and then complicate that by “making” those types of readers gaze at alternative or less “pleasurable” (to them) sexualities.

I was planning on writing a paper about fetishism and commodity fetishism in beto’s work, as I think there’s something to be said for linking these things together….but then I got invited to a different conference the same weekend. Maybe I’ll do it at some point though.

Finally, I think alot of this stuff is fully conscious in beto—and I think if there’s one “body type” that beto mocks and/or doesn’t fetishize it’s the “think, white, wispy” type. Doralis’ defeat of the aerobics instructor for TV viewers is an example of this. There does seem to be a promotion of certain body types (curves, big breasts, fairly big rear end) against others (thin, wispy, no butt)—in his work. This is also clearly linked to race…

I also think that in this case, taking the page out of context doesn’t get you very far. On the other hand, the review is of Hatfield’s book, not beto’s–so, as long as Noah read that…

I did read Charles’ book!

The hermaphrodite/homosexual fetishism seems interesting. You should send me that paper if you ever write it….

“(And Charles has graciously agreed to weigh in himself at the end of the roundtable.)”

Must. restrain. self.

You don’t have to wait! I mean, unless you want to; you’re welcome to start bashing away in comments as soon as you’d like, as far as I’m concerned!

Noah, I’m not sure I understand your distinction between Crumb/Sim and Beto then? Maybe it’s just my English.

“I never read a book before reviewing it. It prejudices a man so.” Sydney Smith. Noah should use that as his official motto.

Hey Matthias. Crumb and Sim are pretty clearly not trying to critique attitudes towards women. Therefore, their misogyny isn’t contradictory. When Hernandez objectifies women, on the other hand, it does seem contradictory to me; on the one hand, he’s trying to talk about issues of female objectification; on the other, he reproduces that objectification in ways that seem problematic (to me at least.) His formal choices seem to cut against what he seems to be trying to do in other respects. Does that make sense?

Hey Jeet. I am happy to respond to your comment, though I confess I did not read it.

Eric B. wrote: “On the other hand, the review is of Hatfield’s book, not beto’s–so, as long as Noah read that…” But to what degree can you make an intelligent critique of Hatfield’s reading of Gilbert Hernandez without being familiar with Hernandez’s work (Noah B. doesn’t even remember with certainty if he read “Heartbreak Soup” or not, which doesn’t inspire confidence.)

Could you write an intelligent and useful analysis of Hugh Kenner’s The Pound Era without ever reading any Pound, Eliot or Joyce (“I believe I read The Dubliners once upon a time”), could you write an intelligent and useful analysis of Yeats without even reading Yeats.

I really think Noah has created a wholly novel form of criticism. In the past we had New Critism which gave us the close reading of texts. We’ve also had Franco Moretti’s distant reading which looks at the global social and political structures that texts circulate through.

But now we have Noah Criticism (or No Criticism for short) which involves not reading the text at all and just offering pure attitude and posture.

” just offering pure attitude and posture.”

He says, offering little himself except self-satisfied snark and pedantic whining.

Really, Jeet, you’re whole above-the-fray-while-dripping-snark thing is kind of embarrassing, don’t you think? If you want to throw punches, throw punches, but don’t pretend that you’re defending elevated discourse while thrashing about in the muck.

I do agree that maybe it wouldn’t hurt to have read Hernandez before staggering down this road… but, hey, it’s a blog, not The Pound Era.

I prefer to see it more as lurching….

I’m sorry if I was being snarky. Okay, let’s reword my objections in a more constructive way. Noah: when you actually sit down and read something carefully, your criticism can be very rewarding. I’m thinking here of your Winsor McCay pieces. What I find much less useful are the essays where you offer opinions on works that you haven’t read.

On a more specific point, I’ll take issue with this: “Crumb and Sim are pretty clearly not trying to critique attitudes towards women. Therefore, their misogyny isn’t contradictory.” I really think it depends on which Crumb story and which Sim sub-story you read. Some of Crumb’s work is purely an expression of sexism but on other occasions he’s actually trying to assimilate feminist ideas (his use of Savina Teubal’s reading of Genesis). Sim is also complicated because there is evidence both in the comics themselves that in the early years of doing Cerebus he had some respect for feminism and was trying to deal with it respectfully. Sim went through a lot of changes and the Sim we know today isn’t quite the same the Sim of the early issues of Cerebus (although here and there you can also see evidence the “the child is father to the man.”)

I’m not a huge fan of Sim’s work but there’s a lot of complexity there that needs to be grappled with. And what’s true of Sim is a hundred times truer of Crumb and Gilbert Hernandez.

Hey Jeet. No need to apologize for snark! It’s the internet after all.

I don’t actually disagree with you about Crumb and Sim, and probably not about Hernandez either. I guess I’d probably quibble a little, and put Crumb with Sim and Hernandez as the one for whom complexity is a hundred times truer on this particular issue (the use of feminism in Genesis is…well, best not to talk about it probably.)

I think Hernandez’s attitude towards women, as expressed through narrative and imagery, is fairly contradictory, and even confused. Sim and Crumb seem to be less conflicted (which isn’t the same as “not conflicted at all.”)

My difference with Charles isn’t that he claims a critique which isn’t there, but that the critique is to some extent contradicted (not nullified) by the formal elements he discusses. At least to me.

I’m hoping maybe to have a pretty substantial post about Crumb and feminism by a guest poster in the next couple of months if I’m lucky.

And thanks for saying nice things about my Winsor McCay pieces. I appreciate it.

Trying.not.to.get.sucked.in…I’m still writing my own…but I wanted to say that — for what it’s worth, my not having read a lot of either — I tend to find GH’s women less objectifying than Crumb’s. My gut tells me GH is a little more complicated. But it definitely doesn’t make me go “ooh, this book likes me!” I’d say problematic, but not simplistically so.

Which would be my answer to Matthias, that yes, in the West, contemporary art that’s problematic on gender issues in a simplistic way is lesser art. It represents and often validates a narrow subjectivity, inconsistent with the condition of gender politics in the West, which, if simplistic, is disengaged and reactionary. If it’s an exceptionally powerful representation of that subjectivity, one that taps into the inherent nuances and contradictions and distortions of any subjectivity, it will be complicated enough that this won’t apply. But very few works of art are that powerful, even historically. Most are cultural artifacts. Gender politics, and the politics of what counts as art, are not simple issues here, and art that treats them as simple is simply too disengaged from the cultural moment to be powerful. Contemporary art that makes the choice to do so is lesser. Furthermore, the desigation of “art” onto a creative object is not an objective process. We do not live in an age where art and politics can be sequestered, so attempts to depoliticize the content of that art or the process by which objects become considered “art” is attempting to aestheticize a conversation that has already been politicized — and that aestheticization is itself a political act.

Perhaps, in GH, the “gaze” is not so much “male” as it is a cluster of different, possibly competing subject positions — particularly the Latino one with its tendency to fetishize curvy women. I haven’t read enough to tell, but it seems possible from what I have seen to read GH’s work as an expansion of gaze theory itself, comparable to bell hooks’ work, as critiquing a kind of universal male subjectivity that is, by default, white, western, and I think, characteristically mid-century (i.e., the “male gaze” of Judd Apatow is not the same as the gaze of Terence Young is not the same as the gaze of Gilbert Hernandez is not the same as the gaze of Christine O’Donnell is not the same as the gaze of [insert here].)

I’m not sure how elaborate GH’s critique is though, and whether it is sustained enough in the work to mitigate the problematic elements…I would assume it’s not as self-conscious as hooks’, right?

Again, less objectifying than Crumb is a pretty low bar…but Hernandez definitely clears it.

And my impression is that a lot of women do like Hernandez’s work. I think Charles talks about this, actually…that one of the draws of Love and Rockets was that it was far more female-friendly than mainstream comics.

quickly:

But I’ve yet to hear anything from you, from Charles, or from anyone else that confronts the way those complex effects do or do not deal with the compulsive fetishization of women, or with the way that the narrative disjunction appears to feed into that fetishization.

my whole point continues to be that you’re looking for something in hernandez’s work (namely, some form of articulate auctorial discourse about the fetishization of women) that just isn’t there. i don’t see what there is to confront in the first place.

I just think it’s an aesthetic problem to (a) attempt to present sympathetic female characters; (b) fetishize women compulsively; and (c) not really have any idea why you’re doing those things except that it feels good or it’s a good story (or whatever.)

I don’t think that’s actually what Hernandez is doing, by the by. He’s got more of a handle on his aesthetic choices than that (or you) suggest — or at least it seems like he does to me.

so if i understand well, you think there’s an aesthetic problem in something that you don’t think hernandez is actually doing. is that getting us anywhere?

again, i don’t want to suggest that hernandez works without thinking about the implications of what he draws. but neither do i see any kind of systematic discourse/theorizing in his work. the “problem” is just too blurry to be examined from the narrow lens you insist on using.

I don’t think there needs to be systematic theorizing. But…he draws women as enormous-breasted pin-up models. That’s a choice. Why did he decide to do that? Charles and I have somewhat different answers to that question. But I don’t think it’s a blurry question (though the answer can be somewhat complicated, of course.)

I also disagree with your claim that gender theory is a particularly narrow lens, or one that’s opposed to Hernandez’s concerns. So we may just have to agree to disagree, I suppose.

david t:

I think it needs to be argued that Hernandez avoids the “aesthetic problem” (although I’d say it’s a political problem, given the tendency here to treat aesthetics as apolitical). It’s not immediately apparent on a casual read that those women are fetishized in anything other than the most blunt and unhelpful ways, so a tension arises with the sense that they’re “female friendly.” That tension needs to be accounted for — it’s curious — and generally, critics would accomplish that via a synthesis of the analysis of formal elements with that of content.

I don’t know if that’s what Noah was getting at when he said “seduced by form” but that’s the way I took it.

I second the objection to gender theory being a “narrow lens.” Gender theory makes the point fairly aggressively that the idea of a gender-neutral “wide lens” is a “male” bias (where “male” signifies the systematic restriction of the universal subject to male subjectivity.) The lens can’t be wide if it’s excluding half the population.

Yeah, that was my point in general. I think Charles takes a stab at doing this; I just didn’t find his take entirely convincing. (It wasn’t entirely unconvincing either.) Eric points in an interesting direction too by arguing for a consideration of the queer content in Hernandez’s work.

I find it a little hard to believe that this sort of thing hasn’t been discussed in relation to Hernandez’s work before, actually. Suat or Charles? Any links?

Caro, thanks, but you do realize that the normative framework you’re espousing re: the aesthetic value of art is just as (inter)subjectively constructed and political as one that, say, aspires to pure aesthetics, right?

My point is simply that a too strictly formulated ideological framework (whether politically, socially or aesthetically determined) will tend to dismiss out of hand anything that doesn’t fit it, without really considering it in more depth.

Sure, Matthias. But feminists have spent the last 60 years specifically critiquing the framework that aspires to pure aesthetics, on the grounds that there’s no such thing as pure aesthetics. The personal is political. The aesthetic is political. Every single time anybody represents a woman’s body, it’s political. Sometimes it can be good politics, but everything is political. Including the statement that everything is political.

It doesn’t mean critics are obligated to talk about the political elements of art at the expense of any other aspect, but a systematic, philosophical/critical framework of “pure aesthetics”? I’m not buying it.

Insofar as it’s a “strict” ideological framework that the perspective of women must be taken into account, I’m ok with that as a limitation on freedom of discourse. But I wouldn’t consider the feminist position to be exactly a “strictly formulated” ideological framework in any practical sense: feminists disagree internally over the specific manifestations and implications of this politicized discursive space. For example, there were no critics of Irigaray as ferocious as the Anglo-American feminists. But they still agreed on that premise, so I don’t see how anyone can explicitly eschew “the personal is political” without being actively anti-feminist.

The idea that there’s some neutral framework that gives “more depth” than the feminist one is the same idea as that “narrow lens.” The feminist critique is not one of specificity; it’s one of expanded generality. I don’t know of any aspect of that neutral framework, any foundation for that neutral framework, that feminists haven’t already addressed sometime in that last half-century.

So advocating a return, at this historical moment, to the very discourse they worked so hard to explode, to me, is either an overtly anti-feminist political act or something that requires a theoretical defense against those specific critiques. It’s not impossible to return. But the return has to be dialectical, or else it just calls for a reiteration of the critique. I remain unconvinced that the return as it’s been formulated here (and a few other places) is actually sufficiently dialectical not to warrant that response.

There are more dialectical formulations, though. I recommend the introduction to Sarah Nuttall’s book “Beautiful/Ugly” for context.

gender theory is interesting. it’s one more tool from the critical toolbox. i don’t think you can build a house using just a hammer, though. which i suppose is also matthias’ point.

It defeats the whole point of feminism if you only apply it sporadically.

i.e. the lens is narrow because gender theory is all there is to it. in which case you might as well be looking at a car, or a lamppost. who cares that it’s a comic that might even be telling a story? all we’ll do is skim the surface & make grand general statements about it. & then we wonder why things seem more complicated than the tiny morsel we managed to grasp.

Maybe we’re just not meaning the same thing by “gender theory.”

Gender theory, as practiced by Judith Butler or Toril Moi or Luce Irigaray or Elizabeth Grosz or Teresa de Lauretis et al., encompasses everything from psychoanalysis to deconstruction to history to activism and performance and offers both a general approach to culture and an extremely comprehensive theory of subjectivity, male and female and otherwise. There’s nothing in the least bit “narrow” about it. If you have a critique that pays attention to culture or subjectivity, and you omit that perspective, that’s the narrow lens. Ignoring it is the critical equivalent of what Jeet accused Noah of doing — not attending to all the relevant literature.

A gender-oriented critique that just skims the surface of its object is either just a bad critique or merely a set of suggestive questions and not a finished critique at all…

A lot of academic writing at this point, though, is post-feminist, in the sense that the assumptions are consistent with this macro-scale feminist critique so it’s not addressed directly. But feminists remain vigilent about cross-checking those assumptions.

“the lens is narrow because gender theory is all there is to it. in which case you might as well be looking at a car, or a lamppost. who cares that it’s a comic that might even be telling a story?”

Hey David. I think you’re coming from an assumption that narrative, or story, is (a) primary in any discussion of a work of literature, and therefore, (b) apolitical and (c) broad. At this point in history, those are all big, big assumptions to make. Even critics who are really skeptical of feminism (like Harold Bloom, for example) would have trouble defending such a focus on narrative — I mean, what do you do with Finnegan’s Wake then? Or even Virginia Woolf or Faulkner? Or for that matter, the fragmented narrative that Charles points out is central to Hernandez’s work? And what do you do with the fact that comics includes pictures — if narrative is primary, what happens to style, or page organization? Are those always supposed to be subordinate to story? On what grounds?

It just seems like in your desire to eschew all but the most common sense approaches, your throwing out much of what is great or interesting not just in literature, but in Hernandez specifically. I can’t help but think that’s a bad idea.

we’re mostly not meaning the same thing by “narrow lens”. the lens i’m refering to is noah’s, not gender theory’s.

To respond — *very* belatedly (stupid time-zone difference!) — to Matthias: I very carefully didn’t say that Hernandez was a lesser artist because of his representations of the female form. I wouldn’t necessarily say that about Sim or Crumb, either. I like both those guys too.

(Sim in particular is about a million times more complicated on gender than you would think. One of the interesting things about Cerebus is how Sim’s explicit proclamations about women, both inside and out of the text, clash with how he actually portrays them)

Matthias — If you’re actually interested in the implications of the issue you raise vis-a-vis the “universality” of the political, I highly recommend one of my favorite books, in which Zizek, Judith Butler, and (the incomparable) Ernesto Laclau have a series of dialogues about the status of universality in contemporary theory: “Contingency, Hegemony, Universality: Contemporary Dialogues on the Left.”

It’s very philosophical, but Butler does a pretty good job of anchoring it into this very debate. (Although I personally agree with Zizek’s take, which I think marks out a blind spot in Butler’s discourse, and effectively addresses your point in a way that ultimately bolsters Butler’s aims, despite her objections to his language.)

noah, the problem with this being a blog & my comments being blog comments is that i don’t have the time or space to spell out my entire critical prejudices (because yes, i think all critics have their prejudices & it’s probably better to know them than to ignore them).

of course story isn’t all there is. neither is the art, social context, history, intertextuality, gender implications, etc. to a critic they’re all potential objects to look at from various angles, all of which should probably be mixed & matched to get to as panoramic a picture as possible. of course, limitations arise in what perspective you can truly master as a critic, in which case, as caro points out, you’ll make informed assumptions.

the reason i insist about poison river telling a story is that nowhere in your (or caro’s) musings is that ever a concern. i could have just as well brought up hernandez’s latin-american cultural origins — but it’s not a subject i know much about, even though i have a hunch it would also give us some cues.

to give an adverse example, this surface reading is probably a lot more pregnant when discussing marston, simply because the narrative serves a secondary purpose: to put it quickly, it’s sort of duct-taping a hodge-podge of strong scenes together, which allows for a more fragmented reading. poison river is much more of a whole: analyzing just one page here & there sounds (again) very slippery to me. but maybe at this point, as you have suggested, we’ll have to “agree to disagree”. i’ll just mention that we’re both coming from vastly different critical traditions, which don’t talk to each other that often (& have probably much to learn from one another).

David: my impression of GH’s work is that the story is often very “female-friendly” and is therefore in tension with those representational aspects that Noah’s gender studies perspective finds problematic. That’s what I was getting at when I said:

I agree that a critic would absolutely have to address story and character and all the conventional narrative elements to examine that terrain sufficiently to account for the tension. If you’re only looking at one page you’re not doing an analysis of the work. But looking at one page, at one formal device, or one juxtaposition can generate interesting critical questions, or serve as an example…

Caro, I’m aware of all that and wasn’t criticizing feminism especially, neither do I believe one bit in “pure aesthetics” — I was merely pointing out that your prejudices as to the relative values of “problematic” art are as constructed and dependent on context as everything else, and by extension suggesting that such art might actually be just as interesting or worthwhile as entirely “unproblematic” art, if such a thing exists.

Furthermore, I was criticizing the kind of judgment that takes something that at face value appears, or even is “problematic”, in a work and dismissing it out of hand because it doesn’t fit one’s political conceptions of how art should behave. I’m not advocating attempting to separate entirely ethics and aesthetics, merely pointing out that a strongly formulated political stance when applied to art often tends to prejudice one’s appreciation of of the work before any real engagement takes place.

Thanks for reminding me of that book — I’ve been meaning to read it for some time.

Matthias —

It’s an extremely well-done book. Although I always wish there was a third round of essays, the dialogic format is a very effective way to treat these issues, which — as you’ve pointed out before — are very finely nuanced differences within the dominant contemporary academic approach to the study of art and culture. I’d be very interested to hear what you think of it, where you agree and disagree.

I would probably say that unproblematic art doesn’t exist – but that capital-A Art that is entirely unaware of the ways in which it’s problematic is extremely rare (that’s the point about “simplistic” work in my earlier comment).

I don’t think I dismissed GH’s work; I suggested it might be possible and interesting to read the problematic element Noah identified as an expansion of gaze theory to include the elements of Latino race and culture that GH is often explicitely (not exclusively) concerned with, so I’m going to assume that is leveled at Noah and you can let me know if you think what I said is also too dismissive. It certainly wasn’t meant to be.

I do object to the idea that critics shouldn’t have “strongly formulated” vantage points. Consider how, if everything is political, then “a strongly formulated political stance” is equivalent to “a strongly formulated critical stance” and “a strongly formulated aesthetic stance”, which makes it very hard to avoid without failing to have a well-defined critical perspective altogether. What is the difference btween “strongly formulated” and “well-defined”? Your formulation leaves me in a quandry with regards to what stance you DO advocate a critic start from.

It seems to me you’re suggesting that the “appropriate” critical stance is dictated by “the work,” but the particulars of the work are not independent of the stance. TWO “subjectivities” are implicated in a reading, and therefore in the work of criticism: that of the art and that of the critic. Criticism is intersubjective in the same way that art is intertextual. So which is the ground for you — a criticism that recognizes the subjectivity of the critic and therefore allows for readings from a “strongly formulated” vantage point (as well as gentler readings, see below) or a criticism that subordinates the subjectivity of the critic to the objectivity of the work?

The idea of avoiding overtly political stances in order to allow an experience of the art work less mediated by the subjectivity of the critic, seems like the latter, but that is ALSO a “strongly formulated political stance” on the possible and proper approaches to a work of art, it’s just one that isn’t made explicit by the work of criticism to nearly the same extent as the one I tend to start from. It’s just very political to say “start with the work.”

None of that is to say, pace david t’s comment, that textual readings aren’t an important part of fully fleshed out works of criticism. (Sometimes I feel like this recurring argument has more to do with the fact that blog posts usually aren’t fully fleshed out than it does with actual critical approaches.) But broadly, I think it’s the idea of “engagement without prejudice” that seems so difficult to me…how is that even possible, especially after the feminist critique of objectivity? The problem with readings that claim to start from “the work” and that privilege the work throughout is that they don’t fully account for the ways in which the critics’ subjectivity is always implicated from the beginning, even if the critic’s subjectivity involves the cautious and deliberate gesture of trying to see past the critic’s subjectivity to identify the work’s “own terms”.

Art just doesn’t “wash over” everybody in the same way, and sometimes the awareness of that leads to a “strongly formulated” subjective and critical vantage point. This seems to me related to Francoise Mouly’s point that you found so depressing when we I mentioned it a few posts back…

I realize this part of the thread isn’t really going anywhere, but I wanted to pick out Jone’s comment-

>>>(Sim in particular is about a million times more complicated on gender than you would think. One of the interesting things about Cerebus is how Sim’s explicit proclamations about women, both inside and out of the text, clash with how he actually portrays them)>>>

This plus five. Someone could do some very interesting analysis of Sim’s work comparing explicated and implied character nuances.

I wasn’t being snarky—I was making a point.

Your “point…that it’s possible to have insights about a book, even a complicated book, based on a relatively small sample” (and out of context) is what I find hard to swallow. I reread the Palomar stories and Poison River this September and what got me (not for the first time) was the depth, range and variety of characters (male, female, children, the elderly, different races, body types and sexual orientations) and their complicated interactions over a long span of time. I can’t reconcile “Hernandez’s portrayal of female bodies is insistently fetishistic, and that fetishism seems only fitfully integrated into his often-stressed concern for women” with this rereading. How are the woman “only fitfully integrated”? Their characters (and the male characters’ characters) are front and center. But how can I convince you of that without referring to the actual book, which you haven’t read? If you don’t like the work, that’s your business, but then why spill so many bytes over it? This isn’t just some online diary—it’s linked to from TCJ, and you apparently want to be taken seriously. This issue calls your credibility into account. I could see through it with regards to Beto’s work because I’ve actually read it, but I don’t know a lot about gender studies. How much weight can I now put in your writings on that subject?

For the life of me I can’t figure out what sort of formatting this site’s comments take. Any help?

Andrew: “This issue calls your credibility into account. I could see through it with regards to Beto’s work because I’ve actually read it, but I don’t know a lot about gender studies. How much weight can I now put in your writings on that subject?”

I don’t worry a ton about credibility in this way. And I don’t have much desire to be taken seriously in the manner you seem to be suggesting either. As I suggested earlier, blogging — hell, writing — is not about covering your ass so some random guy on the internets will respect you.

You say you don’t trust me…but I’m the one who told you I didn’t read the book, you know? If you really don’t trust me, why accept my word on that? And if you do accept my word on it, where’s the problem with dishonesty?

When I write, I try to be clear about where I’m coming from. For reasons Caro discusses in her comments here, I think that kind of explanation is more useful and more honest than some sort of claim to objectivity, to lack of prejudice, or to omniscient knowledge.

“But how can I convince you of that without referring to the actual book, which you haven’t read?”

I mean, are you afraid of spoiling it for me? Or what? If you want to convince me of something, write what you’ve got to say drawing examples from the text. It should be easier to win the argument since I haven’t read the thing, not harder. If you don’t want to put the effort in, that’s cool too, but that’s not a problem I’m causing.

Also…you were of course being snarky at the same time as you were making a point. I’m being somewhat snarky too. It’s not a crime. Just fess up and move on.

Matthias and David t. — I just wanted to clarify that I’m not dismissing Hernandez’s work wholesale. He’s not an artist I like a whole lot, and I think the problems I talked about are real problems, but that doesn’t mean that what I said is the only thing to say about him, or even that I personally hate his work (I’m more indifferent.) I mean, just in general I don’t ever write something thinking, “This is the one and only thing anyone could ever say on this subject.”

Andrew…I’m not sure I understand your question about formatting…? HTML should work in comments if that’s what you’re asking….?

Noah: “I find it a little hard to believe that this sort of thing hasn’t been discussed in relation to Hernandez’s work before, actually.”

Maybe Eric (and other academics) will know. He seems pretty knowledgeable about Beto’s comics. Considering the length of time he’s been working in comics, there’s been very little of any depth written about Beto’s comics in popular venues. There have been discussions of his women as far back as the 80s (the idea of Luba being more than just a “hooker with a heart of gold” for example) but it has mostly been piecemeal.

I think some of your detractors may have a point (albeit a small one) especially in light of your affection for I Spit on Your Grave. Beto is deeply engaged with pulp and how the feminine figure (in all its strangely misogynistic permutations) intersects with it. So think of the insistent use of voluptuous women as a counterpart to the rape scene in the movie. There’s certainly a debt to cartoon pin ups (Dan Decarlo, Eric Stanton, Bill Ward etc.), his ethnic roots and other pulp artifacts but it’s not mere carnality at work here. Eric’s points about the heavy emphasis on gay sex and male genitalia is also worth exploring in light of your concerns. I think someone with a good knowledge of that subculture could do an interesting analysis of Beto’s concerns. Almost all of Beto’s major characters in his main serial are women and they seem to tower over the men (who often appear secondary and weak; presumably why Wonder Woman was brought up apart from the domination aspects in his comics). You could argue that Beto’s very involved variation on that theme is unsatisfying and poorly communicated (in fact, I think his work is *definitely* not for you) but it’s not unthinking. This particular element of Beto’s comics definitely requires a more extensive reading of his comics, the thematic content of which is far richer than this discussion would suggest. However, I think your initial criticism was mainly of Charles’ book (which I haven’t read) and it’s failure (?) to engage fully with that aspect of Beto’s comics. What do you think of the work of Richard Prince?

I don’t know who Richard Prince is!

Comparing the voluptuous women in Hernandez to the rape scene in I Spit doesn’t quite work I don’t think — that rape scene is really, really not eroticized at all; one of the least sexy things ever filmed. But I would be interested in a more detailed discussion of the connection between pulp and feminism in Hernandez…. Maybe Eric will write it!

But it’s not about eroticization, it’s about viewing things out of context. You don’t think it’s possible that many women would find that (or any) rape scene disempowering and complicit in the aggression directed towards women in society whatever its intentions (noble in this case as in many others). There are undoubtedly a number of men out there who would find any form of rape highly erotic, the more distress on the part of the victim the better. The fact that it’s “fiction” makes it even more acceptable from a consumer standpoint.

Hey Suat. Oh, okay…I just misunderstood what you were getting at.

I don’t think women who are horrified by the rape in I Spit are guilty of viewing it out of context exactly. You can make a good argument that it is disempowering, evil, etc., I think. I mean, I would argue that that’s not the case with some vehemence, but I don’t think it’s a case of, if only they saw the whole thing they would understand…..

I tried formatting my second post with html. The tags got stripped and it all turned into one ugly blob of a paragraph. I’ll try again.

I didn’t say you were dishonest—when I said it “calls your credibility into account” I meant it calls validity of your assertions into question, not your personal level of honesty. You can be wrong (and thus not credible) without lying, and criticizing a work without reading it greatly increases the chances that you’ll be flat out wrong. Besides, in the context of the conversation, calling you a liar doesn’t even make sense (I wouldn’t have assumed you’d read it that way, either—what were you supposed to have lied about? Your own opinion?).

I’m not afraid of spoiling the book for you—I’m not trying to convince you to like it, nor even to read it.

All I’ve been talking about since my first post to the last is your position that it should be acceptable to criticize a book based on a few pages taken out of context. This position, I think, is not self-evident, and was objected to before I got around to posting. I would think the onus would be on you to demonstrate the validity of this position. I’m interested in it because this is a meme I’d hate to see propagated further.

In my first post, I used the example of the lists of epithets in the Sotweed Factor to demonstrate that a few pages from one book won’t necessarily give one any idea of either the form or content of the whole work (it was certainly not a book of lists). Your response ignored the point—the importance of context.

In my next post I tried to point out how different my perception of the book read in its proper context was drastically different than when I read one chapter out of context. I concluded irrelevantly that it had become one of my favourite books, which you responded to, while ignoring the main point of the post—the importance of context. I was certainly not proposing that, gosh, if you only got to *know* the work, maybe you’d learn to like it. Whether you like the book is not is not at issue (at least not with me).

Jeet Heer similarly made the point using The Pound Era as his example. You responded indignantly to the snarky way he ended the point, again dodging the actual point of the post. The same point keeps coming up and you continually fail to address it.

I’ve responded to it repeatedly. I will do so one more time. I don’t think there’s anything wrong with discussing a small portion of a work as long as you make it clear that’s what you’re doing. I think it’s actually quite common to do this. The analogies you used to attempt to prove the contrary aren’t especially convincing. Your claim that I’m more likely to be wrong because I explain clearly where I’m coming from seems to me completely without basis. I have disagreed with you; that’s not the same as dodging the point. In fact, I’m pretty sure that the only way you’d think I wasn’t dodging the point is if I just conceded that you were right. Which I’m not going to do, because you are wrong.

Caro, I wasn’t suggesting that you were being dismissive — I was referring to Noah, who I now understand isn’t necessarily either. The problem I often see however, and what seemed to be going on with Noah, is the rejection of a work on the basis of a surface reading that seems to yield a given, easy-to-circumscribe “no-no”, such as “fetishization of women,” when the work might actually be much more satisfying given a closer read, whether it is actually guilty of said problem or not.

I do believe strongly in subjectivity in criticism and have nothing against strongly formulated stances, but they still have to engage the work or discussion in ways that are not rigid or simplistic.

Since the topic has been brought up again, I would suggest that people who don’t like Noah’s position read the book David Turgeon recommends in the initial comments, Pierre Bayard’s “How To Talk About Books You Haven’t Read” which, contrary to its title, is really meant for people who care deeply about books and reading. Far greater minds than Noah’s have taken up his position and discussed its possibilities, “virtues” and even “necessity”. I doubt if Noah would change his mind on the subject even if he read the entirety of Poison River, especially since he has read (or skimmed or forgotten; readers of Bayard take note) Heartbreak Soup which can only serve to mitigate against Beto’s later “excesses”.

“Far greater minds than Noah’s”

Okay, now you’re just being insulting.

“I’ve responded to it repeatedly.”

The only place I actually see you addressing the issue is in post #4. I responded to that in post #14 saying that “More than any comic I’ve ever read, context is everything in “Poison River”.” You’ve never addressed the issue of context. I’ve tried to use the word enough to make your eyes bleed.

“I don’t think there’s anything wrong with discussing a small portion of a work as long as you make it clear that’s what you’re doing.”

Discussing a small portion of a work is pretty common. Normally it’s assumed you’ve read the rest of the work that you’re discussing a portion of.

“Your claim that I’m more likely to be wrong because I explain clearly where I’m coming from seems to me completely without basis.”

Not my claim—a pretty dodgy way of twisting what I said. Nobody at any point has criticized you for *admitting* to not having read the work. They’re criticizing your for *not having read the work you’re criticizing*.

“I don’t think there’s anything wrong with discussing a small portion of a work as long as you make it clear that’s what you’re doing.”

“I have disagreed with you; that’s not the same as dodging the point.”