It is the future.

Acid rain has become too toxic for humans to bear. The city of New Tokyo is too crowded, humanity piles on top of humanity in crowded layers of existence. Billboards float through the air and drive by on streets. The police are a corporate entity, run for the benefit of the zaibatsu who own them. And humans are being hunted by creatures from another dimension known as Lucifer Hawks.

Silent Mobius follows a special squad within the police hierarchy, the Attacked Mystification Police, AMP. The women of AMP all have skills that no police exam can test. Shinto priestess Nami, artificial intelligence expert Lebia, esper Yuki, cyborg Kiddy, sorceress Katusmi, led by the incredibly powerful Rally Cheyenne, combine forces to protect humans from the Lucifer Hawk – and rectify the mistake that allowed them access to our world in the first place. “Our world,” I say, even though this dystopian, Philip K. Dickian vision of the future has not quite yet come to pass. This is classic speculative/science fiction.

What makes Silent Mobius work is that the people in this series are people. They are, despite the unrealistic setting and even unrealer powers displayed, people we might know. The humanity of the characters – the utter normality of their behavior in extraordinary circumstances – is what makes this series so exceptional.

Created by Asamiya Kia, Silent Mobius was serialized from 1991-2003 in Comic Dragon. The manga was collected in 12 volumes, had a 26-episode TV anime series, two movies, several volumes of “gaiden” or supplementary stories, and a number of Drama CDs. Silent Mobius was a spectacular example of a series that successfully crossed readerships and genres in Japan – and in America. The English manga, first put out by Viz is currently being re-released by Udon Press.

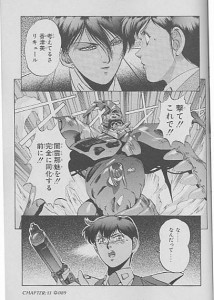

Artistically, Silent Mobius combines dystopian future scifi with an aesthetic that has largely passed from the world of manga – characters that look like the adults they are. The Lucifer Hawks are rendered as complicated shapes that don’t *quite* make sense – there’s a quality they have of making them hard to “see” that fits their extra-dimensionality.

(I had a difficult time finding a good picture, because they are, well…hard to see…)

Last month, I mentioned that I consider Silent Mobius to be an excellent example of a series that passes (and exceeds the minimal criteria of) the Bechdel Test. The story follows a team of women, but is in no way a woman-only world. AMP exists in a man’s world. They encounter sexism in the workplace, all the way to the very top – in the human world and the world of the Lucifer Hawks. They do have conversations about things other then men – and other than work. They talk about coffee or what they did that weekend, and, yes, even their boyfriends. Every conversation is “other than” because real people are not confined to topics “other than” a specific topic. I don’t think the Bechdel Test in any way excludes having conversations about men, just as long as there are other conversations as well.

In short, the women of AMP have lives. Lives frequently include idiotic conversations about nothing. Friends of mine and I recently had a long conversation about flavors of ice cream being hidden in the back of an ice cream shop. Not a notable conversation – which is my point. The ebb and flow of “notable’ conversations is part of what makes the women of AMP so real.

It’s the having of these lives, that are shared during work and some off-work hours but do not overlap completely, that sets this series apart. We see Lebia at home, relaxing with the company of her AI companions, Yuki making coffee at a coffee shop she runs, Kiddy reports about fights dates with her boyfriend Ralph and Katsumi about her time with her lover Roy. Which is the other thing that I truly think makes Silent Mobius outstanding.

Traditionally in manga, when there is a team of female heroes, only the lead character has a boyfriend or the potential for a boyfriend. In a reverse harem kind of bonding, the rest of the team is left to fantasize about boyfriends who will never materialize (or who will, and will be rejected for the greater good, or who will turn out to be evil,) and/or the main character herself.

Not so in Silent Mobius. Kiddy and Ralph, a cop, are arguably my favorite straight couple in all of manga. They fit together perfectly, by which I mean they bicker and bitch and arm wrestle and shout and work together very well. Katsumi’s lover, Roy DeVice, also a cop, is likewise a perfect partner for her. He is loving, sensitive, strong and “gets” that she feels as strongly about working for AMP as he does for his police division. One of these stories has a happy ending, one does not. The rest of the group has perfectly reasonable reasons for not having either a romantic or sexual partner (although Lebia’s relationship with her AI is sort of…suggestive?) And in the context of the story, we’re not constantly questioning why they do or do not have a partner. It’s simply not relevant to the story. And that, in a nutshell is what I think the Bechdel Test represents – that relationships (or lack thereof) are part of a life, and that having them (or not) should not be the *only* focus of the story.

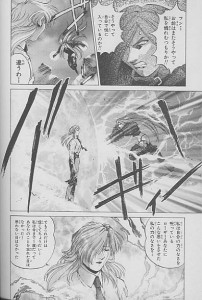

Although not the lead character, the linchpin of the story provides another lesson in how one can write a story about women that isn’t offensive to women. By linchpin, I mean Rally Cheyenne, founder and Commander of AMP. A strong woman, seen here not flinching when she is attacked head on by her own sister, Rally is the key to much of what goes on in the series.

(I love this picture, btw. Rosa’s body is hunched, she is clearly expending all her energy and there’s Rally, looking like she’s walking down the hallway to get a cup of coffee. )

In Silent Mobius, Asamiya provides what I think is a perfectly reasonable answer to the question, “How do you create a series that passes the Bechdel Test?” The answer is simple – have a story about women with lives (and therefore weaknesses and strengths and ups and downs). Make the characters as real as possible, regardless of the unreality of the situation.

It’s not that hard to write about more than one woman who talk about something other than men (or Lucifer Hawks, or family issues or clothes or politics or crime or food….) Asamiya Kia can show you how.

“And that, in a nutshell is what I think the Bechdel Test represents – that relationships (or lack thereof) are part of a life, and that having them (or not) should not be the *only* focus of the story.”

Ah, that’s illuminating. You don’t really like the romance genre, is that right? (There’s a long and honorable tradition of feminists hating the romance genre of course.)

I know you’re out of the country…but maybe you can tell me I’ve misunderstood when you get back….

Silent Mobius is one of those series that I like, but I can’t really figure out why. I think it’s a case where I can read and enjoy one manga series about techno-magic-demon cyber-cop women but not two of them.

Noah – I can’t really say I hate or dislike romance as a genre, although I don’t choose to read romance novels in English. So much of the Yuri I read is romance genre, I’d be lying if I said I never read it.

I once read a Clive Cussler book my Dad had around the house and it was instantly apparent to me that the language was nearly identical to any women’s romance. The men were all bronze gods and the women all lithe and willowy.

There was no point to that last statement, I just thought it interesting. ^_^

Derik – Hahaha! I totally understand. I like the series primarily because I LOVE competent women and Rally Cheyenne makes the series work for me.

Pingback: Tweets that mention Overthinking Things – 11/07/10 « The Hooded Utilitarian -- Topsy.com

Pingback: Hooded mobius | Farestrans