Laughter can topple tyrants. Or it’s nice to think so anyway. When the little child guffaws at the naked emperor, we like to believe that said emperor will blush, admit the error of his ways, and put some pants on, rather than, say, hanging the child from the nearest lamppost and covering his own royal unmentionables by bathing in the blood of anyone in the surrounding throng who happened to utter a sympathetic giggle. When John Stewart gets off a particularly pointed jibe, we like to think it matters to somebody, rather than that it’s just going on to dissipate affectlessly into the virtual ether. Philosopher Simon Critchley may say, “I…want to claim what goes on in humour is a form of liberation or elevation that expresses something essential to the humanity of the human being,” but in that initial nervous “I…want to claim,” and in the over-enthusiastic resort to italics he reveals, perhaps that this statement is as much hope as certainty. He adds, “By laughing at power, we expose its contingency”…and then, with fetching inevitability, he starts to talk about the emperor’s new clothes, that parable for skeptics which we are, of all parables, not to take skeptically. [Critchley 47-48]

Art Young’s Inferno certainly participates in the hope that the jester might threaten the Khanate. Inspired semi-ironically by Dante and Doré, The Inferno is a description of Young’s journey through Hell, circa 1934. This was actually Young’s third book exploring the pit: the first two were Hell Up To Date from 1892; the second, Through Hell With Hiprah Hunt, from 1901. Both of these were cheerful and non-threatening, focusing on devising witty punishments for modern sins. Unfeeling editors are consigned to red-hot wastebaskets, unattentive husbands are dressed in drag, hobos are forced to bathe, and justice is more or less inoffensively dispensed.

In 1906, however, Young became a convert to socialism. The Inferno, written during the Great Depression, is, then, not a light-hearted fantasy about a just universe, but rather a Marxist panegyric, which explicitly uses its humor to castigate the status quo. As I wrote in a 2006 article for The Comics Journal:

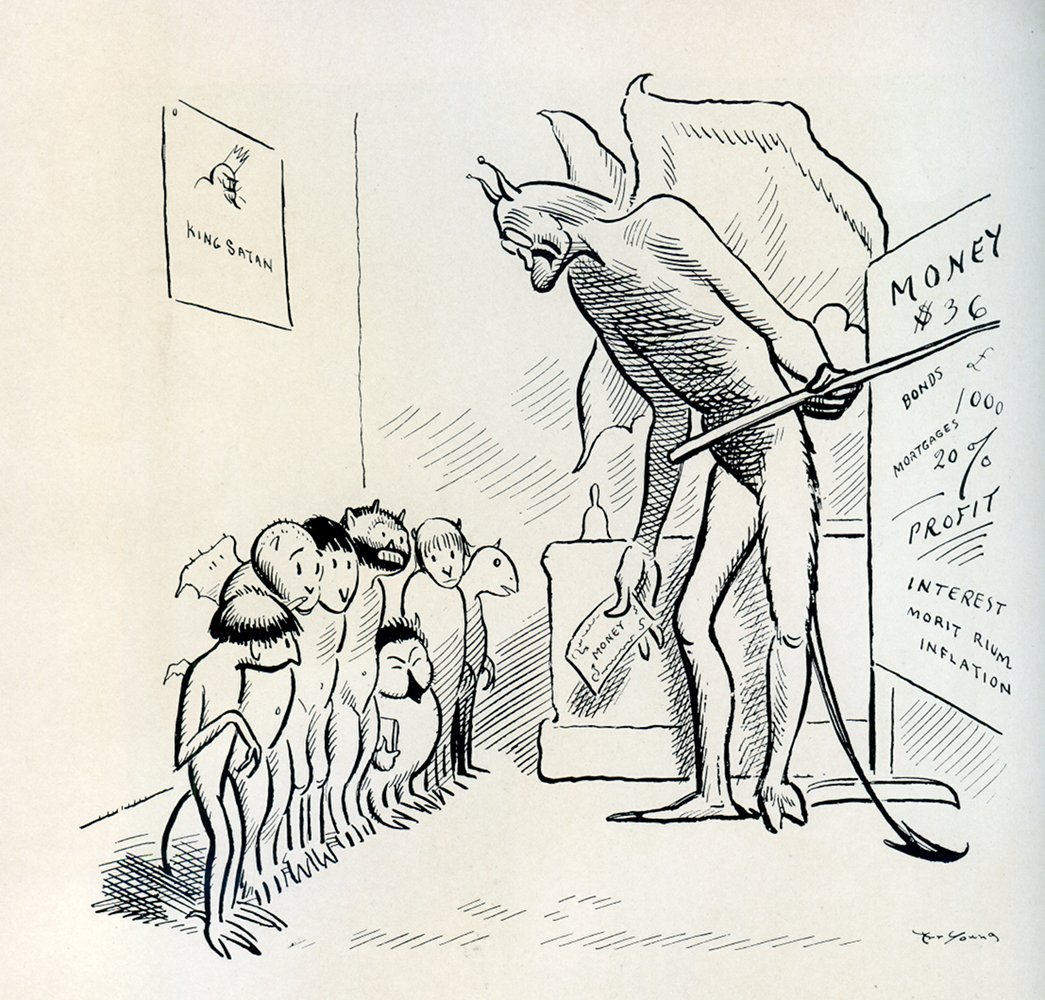

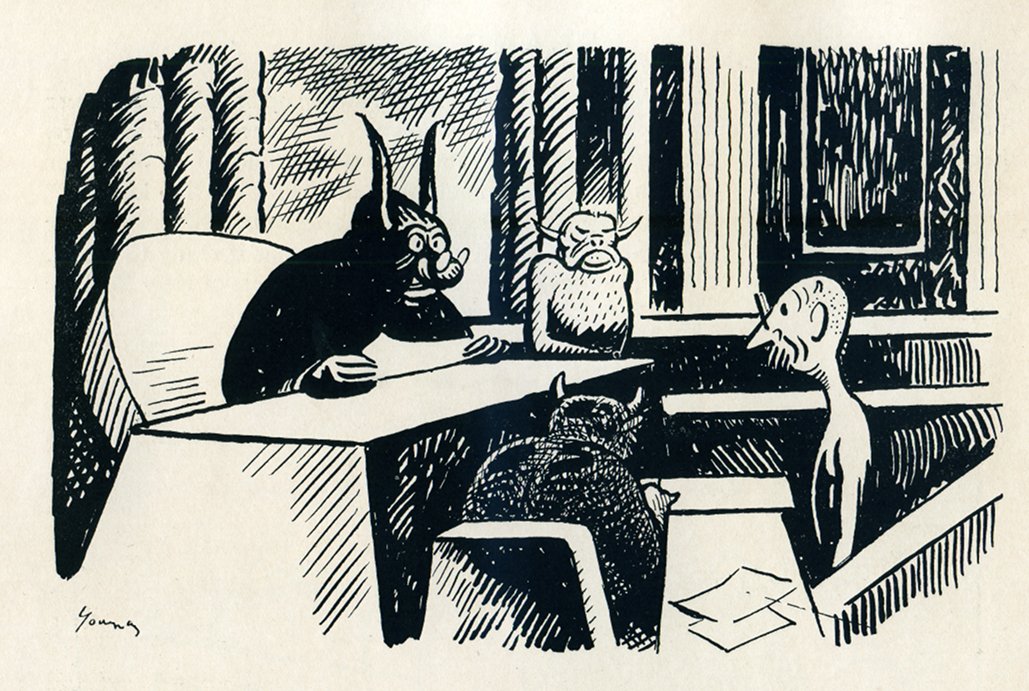

Young reports that “Big Business organizers and Bankers” had been going to Hell in such numbers that they had managed to take over. Satan retains a ceremonial role, but the real power is now vested in an All-Hell Congress controlled by business interests. The new overlords have no interest in punishing the unjust; rather they want to “make money out of Hell.” To this purpose, they establish schools which are “operated like factories to produce standard size thought” and hospitals to which “poor sinners are sometimes grudgingly admitted.” The sophisticated Hellions have even, Young notes, “learned to use the word ‘sorry.’ A gentlemanly Hellion tears out the heart of his brother, spits on it and says, ‘I’m sorry.’” [Berlatsky 133]

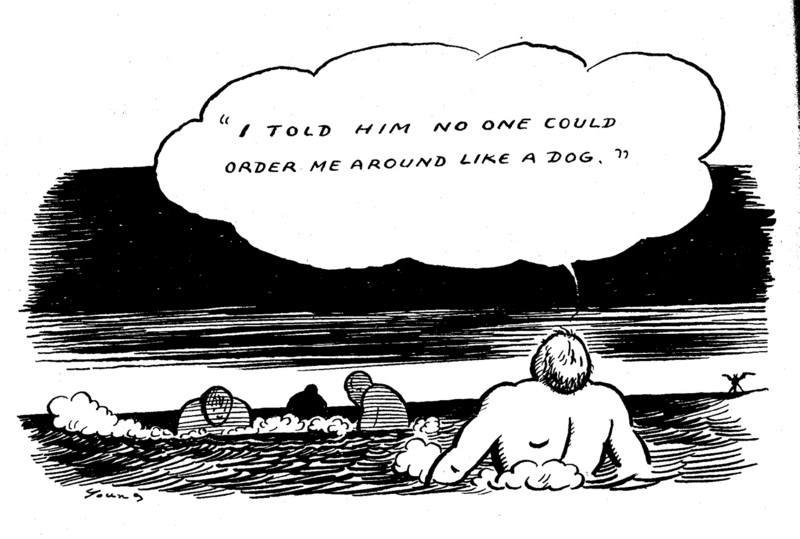

As the above quotes indicate, Young’s text in the Inferno is drily ironic rather than uproarious. His drawings, too, while rendered in a quick, cartoony style, aren’t exactly jokey. Instead, some — like a drawing of adorably confused devil children — are sentimental and sympathetic. Others — like a breath-taking ink-wash painting of the idiot giant war eating people like popcorn — are grimly gothic. Still others, like his drawing of a man waist deep in boiling pitch declaring, “I told him no one could order me around like a dog,” are satirical.

But for all these variations, the humor in Young’s book is all based on a single cosmic joke. This joke is everywhere in Inferno, but is perhaps most succinctly stated in a sequence where Young, exhausted by his travels thorugh hell, goes to visit the doctor. The author complains about he noise of hell and “the fraud, hatred, insolence, brutality, superstition, malice, venality…” To which the doctor responds:

“Man, what do you expect? You know where you are! But there’s nothing to worry about. All you need is a change.”

“A change? Where for instance?” I asked.

“Well, if I were you I’d go right back to earth. You don’t have to stay here, like the rest of us. I could recommend a resort here where the rich Hellions take the cure, but you’d better go back where you came from.”

“Back to Earth! A change! Hell!” [Young 165]

That’s the gag, emphasized by a punning expletive. Hell is earth. Earth is Hell — and will be as long as capitalism is in power.

This seems like a fairly rudimentary laff-generating algorithm. And yet, Slavoj Zizek, another intermittently funny, theology-obsessed Marxist, argues that this kind of unexpected revelation of sameness is in fact the basis of all comedy.

Comedy is thus the very opposite of shame: shame endeavours to maintain the veil, while comedy relies on the gesture of unveiling. More closely, the comic effect proper occurs when, after the act of unveiling, one confronts the ridicule and the nullity of the unveiled content — in contrast to encountering behind the veil the terrifying Thing too traumatic for our gaze. Which is why the ultimate comical effect occurs when, after removing the mask, we confront exactly the same face as that of the mask…. When, instead of a hidden terrifying secret, we encounter behind the veil the same thing as in front of it, this very lack of difference between the two elements confronts us with the “pure” difference that separates an element from itself. [italics in original] (Zizek 56)

The joke is finding that beneath the familiar lies the familiar — the Hell under earth is earth.

Humor then does not cause us to “see the familiar defamiliarized, the ordinary made extraordinary and the real rendered surreal,” as Simon Critchley argues (47). Rather, humor makes the unfamiliar familiar. The humor of Young’s Inferno is not that the ordinariness of earth is rendered extraordinary by putting it in Hell; it’s that the strangeness of Hell is rendered mundane by making it just like earth. Or to put it another way, the comedy is not in self-alienation — in seeing yourself as another — but in the more (or possibly less) profound self-alienation of seeing yourself as yourself.

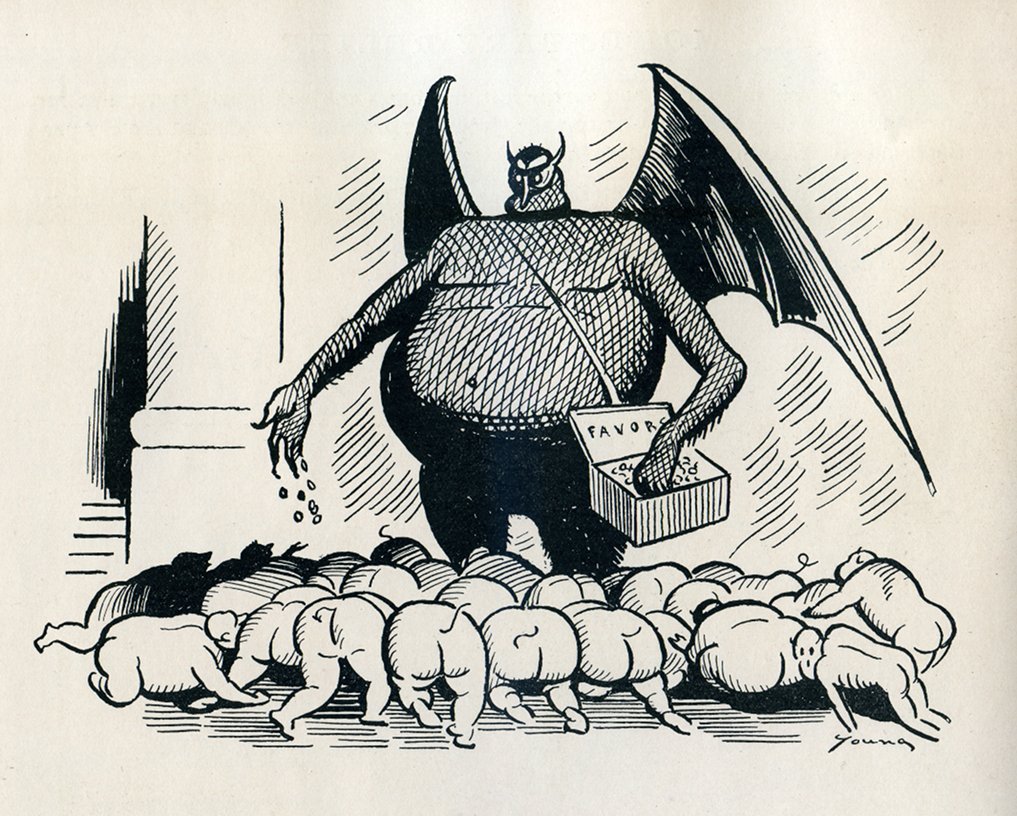

In one of Young’s illustrations, for example, a large devil is shown throwing money to a bunch of rooting, squirming, piglike souls, or Hellions. At the bottom right of the image, one little Hellion turns to look out of the fourth wall with an expression which is possibly embarrassment or possibly surprise.

This is reminiscent of what Zizek calls “the trademark gesture” of Lucy in I Love Lucy who would, when startled, “cast a direct fixed gaze of surprise into the camera.” [55] Zizek argues that this movement reconciles the distance between the actor and the character not by showing they are one person, but rather by affixing the “attitude of self-estrangement” to the screen persona Lucy.

Zizek does not address the other duality however: that between screen persona and watcher. Nor does he discuss the fact that in watching herself, Lucy becomes, essentially, part of the viewing audience. Similarly, the Hellion in Young’s drawing is defined by its awareness of its plight — an awareness which is funny because it is also the self-awareness of the viewer. The self seeing the self sees the self seeing the self in a reflexive bliss of self-identity. This self-identity is separated, by its own obsessive reflexiveness, from the piglike orgy of cupidity and posteriors pictured by Young as the self-annihilating plight of man and Hellion alike.

Young in this image, then, is playing with the disjunction between man as wriggling animalcule and man as observer of himself who, because he can observe, goes beyond the animal. Reinhold Niebuhr, in his essay “Humour and Faith,” argued that this contradiction was the central incongruity at the root of much humor. “The sense of humour,” Niebuhr says, “is…a by-product of self-transcendence.” [Niebuhr 54] In providing a bridge between human weakness (the animal) and human strength (self-transcendence), humor, for Niebuhr, functions as a kind of first step towards Christian faith.

Niebuhr believes that this Christian faith is the only way, ultimately, for humans to successfully face the mystery of being an angel stapled to a dying ape. Thus, according to Niebuhr, “Laughter must be heard in the outer courts of religion; and the echoes of it should resound in the sanctuary, but there is no laughter in the holy of holies. There laughter is swallowed up in prayer and humour is fulfilled by faith.” [49] Niebuhr adds that “there is no humour in the scene of Christ upon the Cross. The only humour on Calvary is the derisive laughter of those who cried, ‘He saved others, himself he can not save….’” [53]

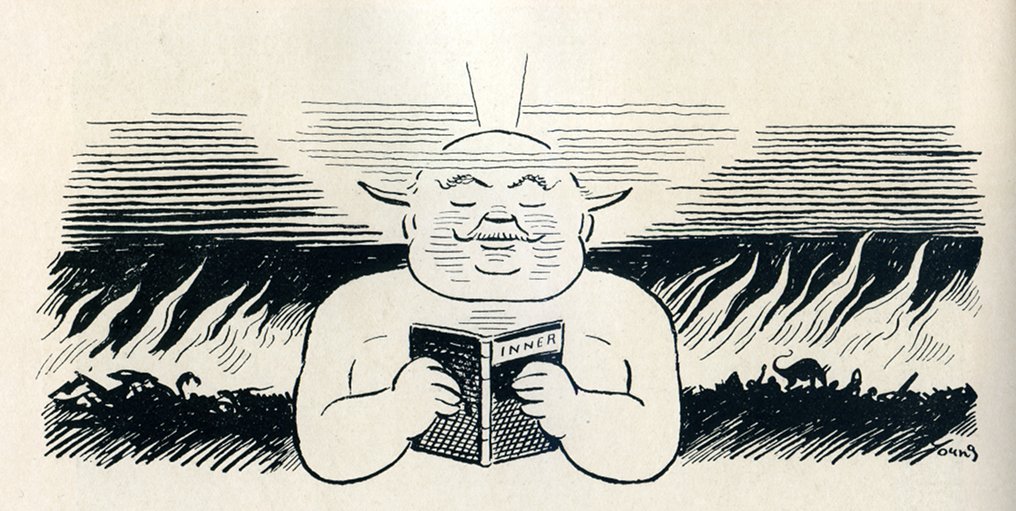

The idea of humor being a station on the way to faith is perhaps counterintuitive. Usually, the black humour of say, Bunuel, is seen as opposed to faith in general and Christianity in particular. Niebuhr acknowledges the potential of humor to detract from faith himself , noting that “when we turn life into a comedy we also reduce it to meaninglessness. That is why laughter, when pressed to solve the ultimate issue, turns into a vehicle of bitterness rather than joy.” [57] For his part, Art Young in the Inferno does not mock Christianity directly, but he does float some heresies — suggesting, for example, that Satan was given Hell not because he was tossed out of Heaven, but because he defeated God and received the Pit as the spoils of war. There’s also a not-very-muted critique of religion in the portrait of the “Inners” who believe “One must make a protective heaven within one’s mind” and who deliberately “become oblivious to the material facts.” [142] Young’s drawing of a typical Inner shows a well-fed Hellion bathed in light and reading from a good book while behind him others burn and writhe and torment one another.

Yet it wouldn’t be correct to say that Young eschewed faith. On the contrary, humor and faith are, for him, intimately connected — even more so than they were, perhaps, for Niebuhr. Humor in Young is not just an analogue to faith, dealing with the same issues, or a step on the way to faith. Humor is, rather, a sword to be used on faith’s behalf.

You can see this most clearly, perhaps, if you look at one of Young’s illustrations showing a mild-mannered devil with glasses preparing to sentence a bespectacled, mustachioed, naked, and non-plussed Hellion.

The drawing has no caption…but imagine that it were juxtaposed with the following lines from the Apostle Paul. Niebuhr claims that there’s little laughter in the Bible, but this sure sounds like black-humor tinged sarcasm to me:

if you are convinced that you are a guide for the blind, a light for those who are in the dark, an instructor of the foolish, a teacher of infants, because you have in the law the embodiment of knowledge and truth— you, then, who teach others, do you not teach yourself? You who preach against stealing, do you steal? You who say that people should not commit adultery, do you commit adultery? You who abhor idols, do you rob temples? You who brag about the law, do you dishonor God by breaking the law? [Romans 2:19-23]

Paul finds (bleak) humor in the distance between the law and the actions of those who profess the law. The law here, the universal, is self-transcendence; the hypocritical action is the animal. But what changes the gap between the two into an incongruous joke — what turns Paul’s face to us like the face of Lucille Ball — is faith.

Young’s faith isn’t Paul’s, of course. But believing in Marx works much like believing in Christ, at least in this context. The little Hellion turning his head, imbued with the realization that somehow, something isn’t right — he has that realization because Young has hope in a system that can make things better. In a 1940 interview, he noted, “I think we have the true religion. If only the crusade would take on more converts. But faith, like the faith they talk about in the churches, is ours and the goal is not unlike theirs, in that we want the same objectives but want it here on earth and not in the sky when we die.”

In one sequence from the Inferno, an anarchist Hellion argues that all of Hell should just be blown up. Young protests:

don’t you think that the working class with the help of socially conscious people — Economists, Socialists, Communists, Social Engineers and perhaps some intelligent Capitalists — will eventually put things right?

The anarchist laughs at him, but Young insists:

We still hope that the upper world will be saved from suicide, and that you and your fellow-workers will learn how to abolish the Capitalist tyranny of the Terrestrial Hell and save yourselves from its duplicate down here. [157]

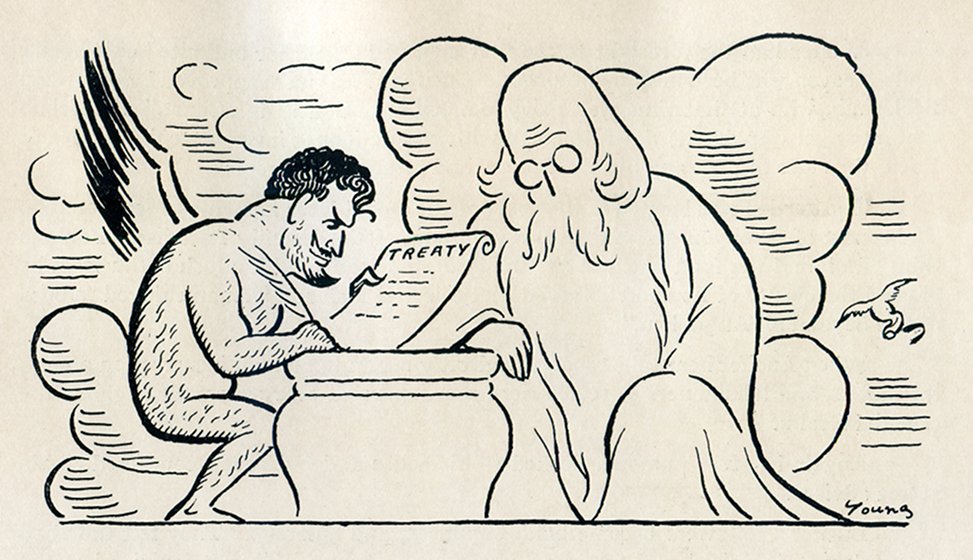

That hope is everywhere in the book — in the excoriation of lives wasted in pursuit of money; of unjust laws; even (in aging old crank style) of the lack of convenient public bathrooms. It’s there too in Young’s one drawing of God.

In this picture, the deity looks out with a blank expression at the reader while he signs Hell over to the cheerful Devil. God’s body posture is mildly slumped and he seems resigned to defeat. But the energy of Young’s quick lines, and, indeed, the goofiness of the caricature — the traditional God morphed into a balding guy with glasses and worry lines — suggests a human creativity that subsumes and may transcend the divine failure. God screwed up, but he’s only human — and in laughing at him we recognize a greater order, and a greater hope.

This is why Zizek sees humor where Niebuhr says there is none — on the cross. The moment when Christ despairs and cries “Father, why have you forsaken me!” is when Christ’s dual nature is most paradoxically incongruous. Christ in his despair is at this moment at his most distant point from God. But in being distant from God, Christ becomes like man — which means that God (as Christ) and man are united. In being, like man, exiled from God, Christ brings man and God together. The black joke, made out of faith, is that despair is hope.

“Or to put it another way,” as Zizek says:

What effectively happens when all universal features of dignity are mocked and subverted? The negative force that undermines them is that of the individual, of the hero with his attitude of disrespect towards all elevated values, and this negativity is the only true remaining universal force. Does the same not hold for Christ? All stable—substantial universal features are undermined, relativised, by his scandalous acts, so that the only remaining universality is the one embodied in Him, in his very singularity. [55]

The nihilist who sneers at the universe, is, for Zizek, the image of Christ. In rejecting all “stable-substantial universal features” through his scandalous act, Christ is the ultimate black humorist, and the cross is the final cosmic joke. Thus, in “Piss Christ,” Andres Serrano submerges a plastic crucifix in a jar of his own urine and photographs it. The result, a blurred shimmering image, is a sneering joke — and that joke is also the meaning of the Cross. Thus, for Zizek, when Serrano or Bunuel or Young use Christian imagery for the purposes of atheist mockery, they are not undermining Christianity, but participating in it. The desecration of black humor is holy.

That holiness doesn’t mean that humor banishes all that’s wrong in the world. Niebuhr argues, quite rightly, that laughter has no power in itself to deter evil, and points out ruefully that “There were those who thought that we could laugh Mussolini and Hitler out of court.” [52] There are those who hoped we could laugh Communist dictators to death too, I’m sure — but here’s Art Young, using laughter on behalf of a 1930s Marxism which was certainly far, far less skeptical about Stalin than it should have been.

That’s not surprising, though, because laughter is not really about deterring evil or bringing down tyrants. Humor is not anarchic liberation. On the contrary, its purpose is to create a structure — a dialectic — to contain the incongruities of faith. You can’t have mockery without a belief in something that is not mocked — you can’t have the ridiculous without a belief in that which is not ridiculed. In The Mysterious Stranger Mark Twain has Satan declare that, “Against the assault of laughter, nothing can stand,” but the statement only has authority because we’re not laughing at Satan when he says it. If we laugh at the Emperor’s clothes we can’t see, it is only because a clothed Emperor rides beside him, invisible but seen by all. Art Young made Hell into Earth not to upend order, but because he believed, with all his atheist heart, that Earth could be made into Heaven.

__________________

This essay was originally commissioned for an anthology on black humor edited by Ryan Standfest. Ryan decided he couldn’t use the piece…for reasons which he will explain in a post tomorrow. So click back then! (Update: Ryan’s post is now here.

___________________

References

Noah Berlatsky, “Building a Better Abyss,” The Comics Journal No. 273, January 2006, pp. 131-134.

Simon Critchley, “Did You Hear the Joke About the Philosopher Who Wrote a Book About Humour?” in Felicity Lunn and Heinke Munder, ed., When Humour Becomes Painful, Zürich, Switzerland: JRP/Ringier, 2006, pp. 44-51.

Reinhold Niebuhr, “Humour and Faith,” in The Essential Reinhold Neibuhr, Robert Mcafee Brown, ed., New Haven: Yale University Press, 1986, pp. 49-60.

Gil Wilson interview with Art Young, May 1940, quoted in “Art Young: Biography,” Spartacus Educational. Accessed: 11/11/10,. http://www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/ARTyoung.htm

Art Young, Art Young’s Inferno: A Journey Through Hell Six Hundred Years After Dante, New York: Delphic Studios, 1934.

Slavoj Zizek, “The Chrisitan-Hegelian Comedy,” in When Humour Becomes Painful, pp. 52-58.

“The desecration of black humor is holy.” This article is SO GREAT!!

I’m just sad that the bands Emperor and Inferno receive no mention. Compare? Contrast?

Aw, thanks Bert. I still haven’t listened to Inferno because I am lame. Emperor is great though.

An important unstated influence was that Return to Forever track…what was it? Ah, google told me. “The Duel of the Jester and the Tyrant.”

And Khanate! I forgot that.

I wonder– eould Young prefer Enslaved to Enthroned?

“Would.” I meant.

don’t think Hell has anything to do with politics

think it’s feeling every pore open up to fire

and lookin at life an thinkin in no objective sense has any effort successfully staved off feeling conscious will scramble frantically thru brain and eat itself in desperation.

u know

Okay, well obviously the problem here is that you’ve never sat through a presidential debate….

haha, rimshot 2012

1. Maybe it’s my faulty memory, but I don’t believe Lucy broke the fourth wall in _I Love Lucy_. Zizek was probably confusing her with George Burns.

2. I think Ryan’s correct that humor doesn’t have to have a positive position to it. Denying something doesn’t entail a belief in an opposing position. That’s why people of various ideologies can laugh at the Marx Brothers. Humor isn’t the same as argument, although it can sometimes be based on solid arguments.

3. As an atheist, I get the joke of _Piss Christ_, but think it’s pretty lame. And, yet, I still don’t get the joke of the Crucifixion, other than as the mocking sort that Niebuhr mentions.

4. Humor as defamiliarizing the familiar vs. familiarizing the unfamiliar: can’t it be both? Lynch practices the former in _Blue Velvet_ (e.g., the fire engine in the parade in the beginning, small town life in general) and Kubrick practices the latter in _Dr. Strangelove_ (e.g., the war room).

5. To say that humor is rooted in faith is to define faith so widely that, of course, you’ll be correct in claiming such a thing, much like how Tillich used to show the religious attitude in everything. That just tends to obfuscate whatever you’re analyzing — humor, in this case.

1.My knowledge of Lucy is shaky, I have to admit. I think Zizek is just talking about a look at the camera, though, not a literal breaking of the fourth wall.

2. Humor involves a belief in the humorist.

3. The joke of piss christ is that it isn’t a joke. It’s a statement of the central mystery of Christianity; the lowest is the highest, and defilement is salvation. That’s the joke of the crucifixion as well.

4. Sure; that’s the dialectic.

5. I’m not saying it’s rooted in faith. I’m saying the mechanics of humor mirror the mechanics of the Christian faith specifically. As Zizek argues, the deflation/casting down of Christ as revelation/apotheosis is the same way that humor (especially black humor) works; the rejection of faith is the finding of faith. It’s not a generalized “everything is religious” argument. It’s specifically Christian. And the specificity is why it’s broader than a vague appeal to humanism, IMO.

Thanks for commenting Charles! When I posted this I was wondering if anyone was going to read it at all….

Hey, Christ himself was quite the humorist.

He had a great skill in dealing with hecklers. “Render unto Caesar those things that are Caesar’s, and unto God those things that are God’s.”

Total pwnage!

This is a fantastic post, Noah. Well done!

Thanks!

jesus christ, the original an hero

It’s a fun essay, Noah.

1. I haven’t read the Zizek essay you use, but “this movement reconciles the distance between the actor and the character” sounds to me like breaking the fourth wall. Lucy was certainly regularly surprised at the mayhem she caused, but looking at us through the camera wasn’t a “signature gesture” of hers. On the other hand, there were a lot of shows, so she might have done some winking at whatnot. This wouldn’t be the first time Zizek got his pop cultural references wrong, but it doesn’t make a difference to your essay.

2. “Humor involves a belief in the humorist.” I appreciate the nod to objectivity here, but a humorist doesn’t equal the position of a humorist.

3 & 5. “[Piss Christ]’s a statement of the central mystery of Christianity; the lowest is the highest, and defilement is salvation. That’s the joke of the crucifixion as well.” This only seems to be a joke if one ignores redemption in the image, that we can transcend the shit, right? I don’t see that Jesus had an “attitude of disrespect towards all elevated values.” He wasn’t a nihilist, but someone offering a different value system from the prevailing one (or, at least, he was offering a different metaphysical grounding for values). Again, this gets you back to an unbelieving mocking of the atheist or whomever to find it funny. A Christian ain’t going to go along with Zizek’s Badiou-esque view that Jesus is another individual with fidelity to a cause. For a Christian, the truth of Jesus existed before the specificity of Jesus. And unless one goes along with Zizek’s interpretation, there’s nothing funny about it. It’s only funny when it happens to someone else’s ideology. It’s possible, I suppose, that a Christian might find some gallow’s humor in the crucifixion, but Zizek’s not providing it. He’s giving an atheist joke on the event, making Chrisitianity participate in atheism, not the other way around. Which is what Young seems to be doing, too.

Hey Charles.

2. I’m probably not following you. I don’t see why a belief in the humorist has anything to do with objectivity, nor why the humorist and the position of the humorist aren’t equal, or why it matters. Satan’s laughter is not just a denigration of what’s being laughed at, but the elevation of the laughter. You’re either laughing with Satan or you think he’s full of shit. If the former, you’re lending him authority.

3. You’re totally misunderstanding Zizek, Serrano, and Christianity. Just as a start, time is really, really important to Christianity; it’s not actually true that the truth of Christianity was true before Christ. Christ is a rupture in time; his presence is the truth. Saying the truth existed before him is, from a Christian perspective (or at least from many Christian perspectives), nonsensical. If you make the truth more than Christ, you move into something like Kant, and/or Arian heresies. Christ’s truth can’t be separated from Christ; his truth is not what he says but who he is. In that sense, he is a nihilist; he’s tearing down without putting a logical system in place. Instead, he offers himself, the destroyer of values — which is the mechanism that I’m saying function within black humor as well. (This is much more Protestant than Catholic, by the by.)

Zizek isn’t saying Christ is just another individual. (Badiou does say that, but not Zizek.) Zizek is fascinated by the mystery of Christianity; he thinks that Christianity has the truth (it just happens for him to be an atheist truth — sort of.)

There is redemption in the image. But the transcendence isn’t in transcending the shit; it’s in being immersed in it. The last shall be first, yes? It’s in the act of crucifixion that there’s divinity; not in moving beyond it or ignoring it but in the actual nails.

For Zizek and Serrano — and this is not at all a rejection of Christianity — the absolute degradation of Christ is the message. The joke is that the degradation is the hope. Mocking Christ on the cross is part of the degradation, and therefore part of the transcendence which isn’t a transcendence.

This is why Christianity is not just another belief among many for Zizek. It’s the belief system which finds transcendence in the rejection of transcendence. Undermining values creates the ultimate value. The joke for Zizek is not that an atheist mocks the Christians, but rather that the atheist mockery *makes the atheist the truest Christian*. That’s not making Christianity participate in atheism; it’s reading atheism through the mystery of the Cross.

Young’s not a theologian…but his Marxism is presented most powerfully through a worldview borrowed from Christianity. When he talks about his dreams, he uses Christian imagery. It that making Christianity participate in atheism? Or is it making atheism participate in Christianity? How can you tell the difference?

I hate to bring this back to the other thread…but Noah says Charles is “misinterpreting Christianity” by suggesting that Christ is true before there is Christ (etc.) because sequential (?) temporality is so central to Xianity. This is true in some ways, but not true in others. Look at Paradise Lost, for instance. God knows that Christ is coming, long “before” he shows up– Christ is part of the (temporal) story, but God is not constrained to linear temporality–in fact, he exists outside of it, knows time in a four-dimensional fashion (or maybe 5th, since God is outside time–looking at it in all of its facets). This is not unique to Milton. Augustine’s discussion of time emphasizes God’s atemporality, as well…and it’s a common feature of Christian ideas about the relationship of God and time. So, I think one could argue that Christ’s arrival is sequential/temporal in one sense (in the sense that he is a human), but not in another (in the sense that he is also God and therefore not subject to human experience of time). So…I don’t think you can dismiss Charles’ claim quite so easily just because Zizek says so… I’m no expert in Christian theology/philosophy…but in the sense of simultaneous time I talk about in the other post (and which seems to apply to God according to some important Christian thinkers), the idea that there is no Christ before Christ is only true in the sense that the word “before” has no real meaning to divinity (supposedly—not Christian myself)

Yeah, I didn’t necessarily want to go there…but the point is that if Christ is true before his presence in the incarnation, it’s because Christ exists before his presence in the incarnation, not because (as Charles seems to be suggesting) there’s a truth in Christianity outside of Christ. It’s simply not true for many Christian theologians that “the truth of Christianity existed before the specificity of Christ.” The specificity of Christ is the truth. You can create theologies where that specificity is present before the incarnation (through prophecy, through having the trinity exist eternally,etc.) But if you make the truth something separate from Christ’s specificity, you end up with the moral law or Arianism. Those are Christian positions too, but Zizek would argue (with a lot of evidence on his side) that they’re more heretical than his stance.

Maybe I’ll ask Bert for his take; he’s a lot better read in theology than I am….

Blah, I’m lost in those last two.

What I have to say on this subject is this: the XI book of Augustine’s Confessions is the classic Christian work on Christian temporality, and Augustine says this:

I read this to mean there was of course Christ before Christ, but only in a place where “before” has no meaning. I think that Augustine is trying to understand in this chapter the atemporality of the Christian notion of eternity.

I am not nearly as well read in Christian theology as Bert, but I think this would mean that because God is eternal, and the divine part of Christ is also eternal, Christ’s becoming human — becoming Christ, both divine and man — is of necessity an entry into time and as such can constitute that rupture – a rupture both in time and of eternal non-time.

Yes, that’s my understanding. There’s eternity and there’s time; Christ’s specificity is in the entering of the first into the second. Separating his specificity form his interaction with time (form the specific place in time and/or from eternity) is contradictory.

You can see the crucifixion as nailing eternity to one moment, too, I think; the sacrifice is being trapped in time (and death.)

There’s actually a logical problem for Zizek here, since he believes that the message of Christianity is that God is dead, there is no God — but then what about before the crucifixion? Was there a God and then Jesus came and there was no God? Or was there a God again when Jesus rose? It’s part of the reason that he’s so focused on the crucifixion itself; his reading of Christianity is centered there. But locating Christ’s truth on the Cross is still (arguably quintessentially) much more orthodox than separating Christ and truth altogether.

Well, yes. At least in Roman Catholicism, the Trinity did not exist in time, but in eternity. Obviously this includes the Christ, the Son.

I think one should also note that the notion of Hell as advanced by Dante and, much later, Young, is a largely medieval construct.

On lunch break– first, real super quick, I’m not a theologian, I just wish I was. I have read about as much as many of you, I expect. I am in fact Christian, but that’s just FYI.

Oscar Cullman wrote a book in the 50s that I read recently, “Christ And Time,” in which he posits a specific time-notion held by early Christians that was distinct from the more Platonic idea of eternity that Augustinians (like Aquinas and Kirkegaard) held to, in which there are two separate realms of time existing at once. I like this, since it allows for the “difference from itself” that Zizek (rightly I think) identifies as central to the Christian idea of the soul. But this difference only has something transcendent (rather than merely “paradoxical”) about it if time really happens as we experience it, and Christ existed as we exist.

That’s all I got right now, but how did this relate to humor? I forgot.

Also, just aesthetically, I think it’s really important to avoid any solemn sense of “profound” humor– cf. the Police “Doo Doo Doo Da Da Da.” Humor is never profound, except insofar as it is never profound.

Oh ok, I think I figured out what’s going on in those two comments. I don’t think you necessarily end up in “the moral law,” Noah. You just have to do what Augustine did, and posit an atemporal specificity for the eternal. It’s still specific, it’s present (in something very similar to the poststructuralist sense, which is part of what Zizek is picking up on); it’s just not part of time. So what Christ marks is the entrance of the truth into the world, not the beginning of the truth. (Of course this is treating it as faith not history…)

If you try to make eternity into something temporal and then argue that Christ’s truth “precedes” the incarnation, you do end up losing the specificity of Christianity in the “moral law” … but in the process that moral law becomes a temporal humanism with a Christian flavor rather than the atemporal deism (deism used there in a neutral not historical sense).

I think the formulation you want is that “the truth (or truth-term) of the incarnate Christ is the specificity of Christianity” rather than the “truth of Christianity is the specificity of the incarnate Christ.” Christ isn’t what’s being specified; Christianity is.

In your formulation you end up collapsing incarnation into specificity, which is a little tautological — but it seems like you’re really trying to sort out the relationship between TWO specificities: Christ and Christianity. The one where you talk about the “truth of Christianity” makes Christianity into one of Zizek’s “universal placeholders” for the truth, which is not invalid, but which isn’t quite the argument you’re going for here, I think, since you’re interested in how specificity changed after Christ, and the universal placeholder is, for all practical purposes, “eternal.”

That last sentence, Bert…sounds like a Wilde-and-soda false paradox. Can you explicit?

Bert, so there are two different times, both of which are time, but one of them is our time and the other is God’s time (which is different form ours but not by being eternal or timeless). Is that right?

Caro, I”m not sure we’re disagreeing…or what the disagreement is, maybe. Charles initial argument was that “the truth of Jesus existed before the specificity of Jesus.” My argument is that the truth of Christ is the specificity. You can think of that as meaning the truth did not exist before Christ, and/or you can think of it as meaning that Christ is eternal, therefore there is no “before Christ”. Either way the truth and the specificity can’t be separated.

Bert, the reason this applies to humor is that Charles is arguing that Jesus did not reject all values as black humor does. Thus his insistence that there is a truth to Jesus outside of Jesus himself. But the point of black humor is the blasphemous annihilation of values…and the replacement of those values with the person of the black humorist himself (or of the experience of black humor itself, I guess.) The crucifixion is similarly a defilement of values and a positing in their place of that defilement itself as holy.

Or, in other words, the analogy between Christ and black humor only works if Christ’s message is himself; it doesn’t work if Christ’s message is some other truth unattached to his specificity.

“I think the formulation you want is that “the truth (or truth-term) of the incarnate Christ is the specificity of Christianity” rather than the “truth of Christianity is the specificity of the incarnate Christ.” Christ isn’t what’s being specified; Christianity is.”

This doesn’t feel right to me, though I’m having trouble teasing out why….

I’m arguing (I think with Zizek) that the specificity of Christ — the actual person of Christ, the experience of Christ — is the meaning of Christ (and presumably of Christianity.) There’s a specific individual, Christ, and that specific individual is the meaning; not what he said, or what he taught, or what you can generalize from what he taught, but his body in time.

So the point isn’t that the truth-term of Christ is the specificity of Christianity. There isn’t a truth-term of Christ; there’s the body and the person, which for Zizek adamently *aren’t* truth terms. That’s why the truth of Christianity is the specificity of Christ (in Zizek’s formulation.)

Again, going back to black humor, this is why you have faith even while you’re destroying all values. You end up with faith in the destruction of values itself; faith in defilement, which for Zizek and Serrano (and not just them) is a Christian faith.

I mean that profound and funny are necesarily antagonistic (Zen Yippie flash mob freak-ins as the textbook illustration), and I would add that Christianity is ideally niether. St. Paul said that if Christ was not resurrected, then Christians “are of all men most to be pitied.” He (and Jesus) both said that love (something, in some sense, subjective and voluntary) is the essence of the Law– which, of course, exisrs as a symbolic injunction that supplements the whole pre-linguistic order of unconscious empathy, semiotic chora, polymorphous drives, unbounded jouissance which Paul reconstitutes in agape. There is something profound here, and ironic, sarcasric even, but neither comic nor tragic. The pathetic (comic) farce of the deluded Christians mirrors the pathetic (tragic) groaning of the earth that awaits redemption.

I think it’s worth mentioning that Art Young cartoons are really not funny– they are epic and grand statements expressed satirically. They are salty and bitter if lovingly crafted spittle.

Regarding the question of the eternal Christ, which Cullman does discuss in his book, is just an expression of the problem of the Trinity. The Holy Spirit is just the spirit that makes people feel holiness (just like Lacan’s Symbolic, Imaginary, adn Real are basically just what they sound like), and that alternately weak and alarming impulse is somehow the same as the force that causes and sustains the universe (God the Father) and one wild-eyed mendicant leader who explained the connection therebetween, leading the world out of bondage by spectacularly failing to lead his people out of bondage.

But I mean, really, is that funny? Or is it just glorious and pathetic, like a demon throwing money to a bunch of groveling pig-men?

You know, I do find Art Young cartoons funny. That demon feeding the pig men; the one pig man turning to look haplessly at the viewer made me giggle. So did your line about spectacularly failing to lead his people out of bondage.

Weird/sad/incongrouous reversals or juxtapositions are actually funny, I think. But maybe it’s just me….

Love is not just the essence of the law but also its antithesis, right?

And I did say that the truth of Christianity was “profound.” I would retract that. This why Paul’s Stoicism echoes systematic philosophical argumentation, but irreverently so. It’s not at all clear that generations of Scholastic and, more recently, fundamentalist interlocutors get that part.

But the annihilation of all values is a dead end. The atheism of humor is one-dimensional, but does reflect the cosmopolitan vector of modernity, which would be great for all of its knowledge and power if only it didn’t cause people to treat each other and themselves as tools toward a completely undefined pointless point.

Yes, I was trying to say that “love is the law” is absurd. Like in that Throbbing Gristle song “United,” which I often sing to myself at the airport.

Well, I’d say that the annihilation of all values in humor is a dead end because it ultimately leaves you with faith in the human humorist, who in the end is just some random doofus. The Christian annihilation of all values leaves you with faith in Christ, who is a specific individual and is also God, which is the paradox. Though Niebuhr, for example, I think would be pretty okay with also seeing Young’s Christian-inflected atheistic black humor as revealing an aspect of the nature of God. (Niebuhr definitely believes that atheists can teach Christians something about Christianity.)

I’m not exactly sure where Zizek is on the destruction of all values. He sort of thinks the transcendent truth is materialism…but his insistence on seeing that materialism as Christian sort of makes you wonder….

Oh, I didn’t mean we were disagreeing, Noah. I was just explaining why I was confused and saying what I thought I’d figured out. If you think we’re not disagreeing, then maybe I figured it out right!

At least, except for the “I think the formulation you want” part, which was conceived as a version of “maybe this is what got me on the wrong track the first time,” but maybe is a disagreement. The problem I have with the specificity of Christ being the truth of Christianity is that it renders Christianity as something material (instantiated). Which may be Zizek’s point but it’s too much “presence” for me. There’s usually an aporia in his thinking somewhere…

I don’t think Zizek is as materialist as you say here, Noah. His project all along has been to reintroduce Hegelian idealism into dialectical materialism, without simply reproducing an opposition between idealism and materialism. So his approach is an idealist materialism, or a materialist idealism, but not “materialism as transcendent truth” — if for no other reason than because Hegel’s truth is not transcendent…

Right; materialism can’t be transcendent. I think he sometimes treats it that way though. I’m sort of poking him.

I do think for Zizek the truth of Christianity is material. If you’re being orthodox, though, Christ is both material and transcendent — so making the truth of Christianity the specificity of Christ is pointing to the materialism/transcendence paradox. I think. Zizek sort of gets rid of the paradox because his point is that God is dead; the death of Christ is about making the human God. But his insistence on seeing this all in terms of Christianity…just arguing in those terms tends to put an asterix by the materialism (maybe that’s your aporia…)

I guess my take on Zizek is that he has replaced the big Other (God) with difference (revolution), which ends up being pretty capitalist-pragmatist, since his core ethic is quantum undecidability, Nietzschean lightness, solipsistic gnosis. The fact that he does this through psychoanalysis and Marxism is pretty intriguing, since it gives him temporary footing to denounce our decadent Western supplemental forms of virruality (decaf coffee being a signature talking point).

One could, in the end, define his “difference” from Derrida and classic linguistic poststructuralism (signifiers deferring forever), as well as Deleuzian post-phenomenology (bodies desiring forever), with a void that somehow (in line with Badiou et al) embraces truth as a motif before mumbling something about set theory and irreducible multiplicity before taking another pithy ironic swipe at multiculturalism.

But I love Zizek, because his vision of a weak God is not something he can write off once he’s brought it up. It’s like trying to beat up a puddle. He points toward a much more clear and unhakeable divinity than John Caputo or any of the postmodern theologians with their full-on Platonism.

On a related note– are you all seeing the ad at the bottom about the comics that does for comic book industry what “Jesus did for a bunch of guys in the desert?” Talk about nervous non-laughter.

Noah,

“it’s not actually true that the truth of Christianity was true before Christ.”

So God didn’t create everything? I’d suggest Christ’s arrival, death and resurrection constitute the proof of God for us temporal beings, not the beginning of God. (No surprise, I agree with Eric here.)

“Christ’s truth can’t be separated from Christ; his truth is not what he says but who he is.”

That sounds right (although it has all kinds of logical problems, such that it seems ridiculous why any atheist would want to hang his own worldview on it), but what it doesn’t do is prove that his truth can’t be separated from the defilement of the crucifixion, or that he’s “the destroyer of values.” Christ is eternal truth, that’s why he could come back. Any truth revealed through Jesus was true before Jesus and is true after Jesus. He was showing us the way through the shit, not that the material conditions of his torture constituted the truth. I’d imagine a Christian would say the joke’s going to be on you for thinking otherwise.

“the transcendence isn’t in transcending the shit; it’s in being immersed in it. The last shall be first, yes? It’s in the act of crucifixion that there’s divinity; not in moving beyond it or ignoring it but in the actual nails.”

I don’t spend much time these days with exegesis (alright, I don’t spend any time), but a little bit of online research suggests that the last-first doctrine is that regardless of your temporal circumstances, you have a chance to go to Heaven. All this muck is transitory and ultimately insignificant. Christ didn’t just get nailed, but he came back, as in look what faith in God can do. Admittedly, I tend to skip Zizek’s writings on Christianity, so maybe he’s dealt with the resurrection, but it seems to be problematic for focusing as you (and maybe he) want(s) to do on the crucifixion alone. Certainly the nails are important, but they’re not the promise (“the absolute degradation of Christ” isn’t “the message”). The crucifixion is, of course, significant, because it shows the insignificance of our current problems in the overall scheme of things.

“Young’s not a theologian…but his Marxism is presented most powerfully through a worldview borrowed from Christianity. When he talks about his dreams, he uses Christian imagery. Is that making Christianity participate in atheism? Or is it making atheism participate in Christianity? How can you tell the difference?”

How can you? I’d say, assuming that Young doesn’t believe in the resurrection and since he’s being critical of Christianity in the way it mixes with capitalism (and not just being critical of the latter) means that his message isn’t Christian, but atheistic, or minimally non-Christian. Showing God signing a pact with Satan the capitalist is pretty solid proof that he’s reading Christianity from a non-Christian viewpoint.

BTW, I haven’t read anything after Eric’s posting, so if I ignored something relevant to my post above, sorry.

“Any truth revealed through Jesus was true before Jesus and is true after Jesus.”

That’s really not right. The covenant with the Jews is changed after Jesus; you were supposed to follow the law before and now you follow love. God created the world, but he also created time, and time matters.

“The crucifixion is, of course, significant, because it shows the insignificance of our current problems in the overall scheme of things.”

No, that’s not the point of the crucifixion. If it were, then people who have suffered worse things than crucifixion (and there are worse things) would have no place in the Christian message. The Crucifixion is significant in itself as a truth. In trying to denigrate the importance of the material, you’re moving towards a gnostic heresy.

I talk in some of the above incidentally about the fact that Zizek focuses on the cross much more than the resurrection. As you say, it’s somewhat problematic…but I think the alternative options you’ve suggested (gnosticism, latitudinarian humanism) are actually more heretical.

Young isn’t exactly critical of Christianity; certainly not in that scene of God signing a pact with Satan (and Satan isn’t a capitalist in Young’s vision, BTW.) Young’s attitude is more sad; not that God (or Satan) has colluded with the capitalists, but that they’ve been defeated by them. Young makes fun of some religious sensibilities, but he also is definitely nostalgic for them. And there’s that quote where he aligns Marxism explicitly with Christianity…. I just don’t think it’s as cut and dried as you’re suggesting.

“The covenant with the Jews is changed after Jesus; you were supposed to follow the law before and now you follow love.”

Isn’t the point to get right with God? Christians and Jews don’t agree about how to do that. They disagree on what the true way is. Changing earthly programs isn’t the same as changing the Truth, which is supposed to be eternal and absolute.

Re: the significance of the crucifixion, I didn’t suggest that the pain involved is the ultimate level at which point your suffering is acknowledged by God. If anything, that seems entailed by your own view, since you care more about the pain (that it’s the message) than what the pain signifies, or what function it serves.

Re: Young, regardless of whether God is colluding with Satan or defeated by him, that’s not a Christian perspective.

I’ll go back and read what I missed later.

“Isn’t the point to get right with God? Christians and Jews don’t agree about how to do that. They disagree on what the true way is. Changing earthly programs isn’t the same as changing the Truth, which is supposed to be eternal and absolute.”

But the New Testament doesn’t say that what the Jews were doing before Christ came was wrong. Rather, Christ coming changed the rules. It changed in particular *how you get right with God.* Jesus died for your sins. That means your sins are forgiven *after his death*. Christianity’s truth is involved in time. It can also be involved, or reconciled with eternity, but it’s a religion in which the event is central. There are paradoxes in that, since the truth ends up being both eternal and involved in time. But you can’t get rid of the paradox by privileging the eternal over the event. If you do, you’re not being Christian; you’ve moved to a vaguely Christian inflected humanism.

In terms of the crucifixion; you said earlier that the signficance of the crucifixion is to show the insifnificance of our problems in the overall scheme of things, yes? That suggests that the crucifixion has to be the worst thing ever; otherwise other problems aren’t going to look insignificant. I’m arguing that that’s a confused view. The point of the crucifixion is not (or not just) human suffering; it’s the degradation of God — the destruction of all values, and the faith that emerges dialectically from that destruction.

“Re: Young, regardless of whether God is colluding with Satan or defeated by him, that’s not a Christian perspective.”

I wouldn’t be so sure. It’s heretical, obviously, but heresy is in a conversation with Christianity more or less by definition. Young’s not reading Christianity through or on behalf of atheism. Rather, he presents an atheism which wishes Christianity could deliver on its promises, and attempts to adopt and fulfill parts of its vision.

But, “officially,” you go to Hell (or Purgatory, or whatever) whether you were doing what God told you or not. If you were a Jew, you went to Hell (or Purgatory, or whatever) even if you were a good one. So, the Truth of Xianity was there regardless….You were just SOL if you had no way of knowing it. Jesus was nice enough to rescue some of the “good guys” from Hell after he rose, but they still had to spend some significant time there…because the Truth (of Xianity) existed before Christ did. (That is, if the value-system of the world really “changed” when Christ arrived, there would have been plenty of “good Jews” dancing around heaven–but since God knows Christ is coming (and all that comes out of it), he can have an “eternal” value-system, outside of time).

I think the notion that someone can be “right” or “wrong” about these things (as Noah keeps saying, “that’s really wrong”) seems kind of ludicrous to me, since people have been debating the finer points of this stuff for centuries. All we have to go on are texts (Bible and others)–so alot depends on the instability of those texts and how open they are to interpretation (very). I mean, my whole claim above is just based on either the Bible (I don’t know that–can’t remember what’s in or out), or “offical church doctrine” at some point in history (which, again, was based on somebody else’s interpretation). The Pope’s supposed infallibility is supposed to solve those kinds of questions (if you’re Catholic), but that’s more of a “get out of jail free” card than an actual solution. I mean, Popes are always changing previous Popes minds about things, so how infallible were they really? (And there’s plenty of versions of Xianity that are not Catholicism, etc.) So…who’s to say what Christianity “really” is? I don’t mind people having their own interpretation based on faith, belief, etc…but since Noah doesn’t believe, isn’t Christian, etc…I have no idea what he can possibly mean when he’s calling other people’s interps “wrong.” “Wrong according to Zizek”? That hardly seems categorical where Xianity is concerned.

““officially,” you go to Hell”

Officially according to whom? Jews were supposed to obey the law and then they were right with God; after Christianity, the law doesn’t apply anymore. “No new wine in old bottles” doesn’t mean there weren’t any old bottles.

If Christ’s incarnation didn’t matter, if the universe was the same before and after Christ, then Christianity is unnecessary. The event has to matter.

When I say, “that’s wrong,” of course it’s for emphasis. I think it’s wrong in terms of what I understand from the theology I’ve read, and in terms of this discussion. I’m not sure why this rhetorical strategy is any less valid than writing a first paragraph in which you participate in an argument and a second paragraph in which you disavow the possibility of anyone being right. If you don’t think what you have to say is in some sense right, why bother saying it?

Not that anyone is all that interested necessarily…but my conviction that time and event have to be central in Christianity is in part from Zizek and Badiou, but it’s mostly from reading C.S. Lewis’ Space Trilogy. He’s very insistent in those books that history in general and the crucifixion (and the fall) in particular matter — and further that they’re contingent. The universe is affected by Christ’s death, and that death was not planned or inevitable. There’s a universal, eternal God, certainly, but time is time and events matter.

For example, before the crucifixion, for Lewis, God made various alien races in various forms; after the crucifixion, all new races are humanoid. It’s kind of a goofy conceit out of context, but the point is pretty clear; Christ’s death happened, and the universe changed.

Again, real fast and sloppy—

The issue of typology is important. People reject God and get punished and then rescued throughout Genesis and Exodus (and elsewhere, but Adam and Moses are pretty central).

Jews going to Hell– in fact, making definitive statements about the afterlife at all– is a much less pervasive hobby among, say, contemporary Presbyterians (with whom I comingle) than it may or may not hjave been in some other place, as a justification of ethnic cleansing or what have you. I think it’s not an issue to overlook, but I don’t think condemnation, by God in the Bible or by real Christians in history, is the whole story on how Christians see truth, salvation, and time.

Christ was prefigured, but he didn’t exist until he existed. He is referred to by Cullman and others as the “midpoint of history.” He has risen and will come again, but is neither present nor absent, much like the Father and the Spirit.

Bert, what do you mean by typology here?

“Typology” is (unless I screwed up) a theological term meaning reading earlier Bible stories as prefiguring later ones, especially as regards the Old Testamanet “anticipating” the New.

Anonymous sources have pointed out that this passage:

“For verily I say unto you, Till heaven and earth pass, one jot or one tittle shall in no wise pass from the law, till all be fulfilled.” http://bible.cc/matthew/5-18.htm

seems to support Charles’ view that the law has not changed. I’m not exactly sure; it seems like Christ’s intensification of the law is actually a change, and one that can also be seen as a negation…

I’m a little bemused by the sight of so many non-Christians (myself included)disputing Christian theology in such detail.

It reminds me of Kierkegaards’s aesthetic fallacy.

I don’t know…theology is one of the central — actually probably the central — philosophical tradition of the last thousand years plus in the west. It seems like that should matter to everyone, whether you’re a Christian or not.

For historic reasons, perhaps, but one needn’t speculate on how many angels can(fill in th rest yourself)

Sure– who needs truth or faith now that everyone completely understands reality completely? Or at least they could if they didn’t want to be ignorant on purpose.

Yeah…I mean we’re talking about the nature of time and event, of law and love, of event and therefore of the possibility of (political) action, of humor, faith, and hope.

Obviously these questions don’t have to matter to you. But it seems odd to insist that they wouldn’t matter to anyone who wasn’t Christian, or that they stopped mattering because our culture is mostly secular now. For me, many of the philosophers and thinkers I’ve gotten the most from are Christian (Kant, C.S. Lewis, Niebuhr, Yoder, Chesterton, arguably Shaw, arguably Zizek, sort of Baldwin), and the nature of Christ therefore is pretty important to how I understand the world, even though I’m a Jewish atheist.

days later…and when nobody else cares…I’ll just say that “officially” I’m not making this shit up. I mean, the notion that Jews and pagans go to hell doesn’t start with me, but with some versions of theology and Christian doctrine. You give me Zizek and C. S. Lewis–I’ll give you Dante, for one (and earlier in the thread Augustine and Milton, etc.)–These are actual Christians and theologians (unlike either of us)…So, line em up on either side.

Anybody who does theology is a theologian in some sense. So you and me count.

I don’t think anyone disputed that Jews and pagans go to hell in some versions of Christian doctrine. Bert said it’s less central than some folks like to make it out to be; I suggested that Christ’s coming changed some of the rules of the law. That’s not necessarily incongruent with Dante and Jews in purgatory, I don’t think. (The point being that *after* Christ’s coming, if you reject him, you don’t get to go to purgatory at all.)

I’m a little shaky on this, but the problem of what to do about pagans who didn’t have the truth revealed to them has actually been a major theological issue, I’m pretty sure. It was a huge deal in the European encounter with Indians; could they be damned when they’d never gotten to hear the good news? The question was somewhat different than a historical, pre-Jesus issue of pagans and Jews precisely because Jesus’ incarnation was seen as changing the requirements for getting right with God…

Well, the Catholic Church is explicit about this.

If you’re not a Christian, you are damned to Hell, even if you lived before Christ, no matter how righteous or virtuous you were. Period.

This caused some awkwardness. How could the University or St Thomas Aquinas invoke Aristotle? What of the many righteous Jews and prophets in the Old Testament?

So the Church created a work-around.

These good pagans and Jews were either a)rescued by Christ during his 3-day descent into Hell (the Harrowing of Hell), or b) consigned to a nice part of Hell called Limbo, described in detail by Dante– a place they shared with babies who died unbabtised.

Noah, really, be wary of wasting your energy here.

Oh, pshaw. It’s much more fun to talk theology than many other things I could be doing….

Yes Noah, be careful, or people will think you want all of your closest family and friends to burn eternally.

I mean seriously. Does anyone think there are a whole lot of Christians who are nostalgic about the pogroms or the Inquisition? Or, perhaps, like most communities, rational Christians believe their damaged and bloodstained institutions are worth reforming.

If you don’t think scientistic secularism can be reformed, why don’t we all just live in totalitarian Germany/Russia/China? It’s not like the tenured academics of the world don’t have some things to apologize for; weapons of colonial massacre, anyone? Why vote for a black president in the land of slavery and native genocide?

It’s because guilt is going to be central to any social edifice. That’s Freud. But it’s worth keeping around some reminders about the dangers of blithely pointing out other people’s transgressions.

I think to count us as theologians is crazy…but we probably won’t go to hell for it.

Christianity — or at least Protestantism — has a fairly strong commitment to the idea that the book’s message is for everybody, not just professionals.

You certainly don’t have to be a scientist to discuss science, or a doctor to discuss medicine. In fact, it’s hard to see how anyone could ever apprentice anything if they had to be an expert to even think about it.

Disciplinary anxiety is perhaps the most salient theme of discussions on this blog. Or am I wrong?