“I prefer the films that put their audience to sleep in the theater. I think those films are kind enough to allow you a nice nap and not leave you disturbed when you leave the theater. Some films have made me doze off in the theater, but the same films have made me stay up at night, wake up thinking about them in the morning, and keep on thinking about them for weeks.”

Abbas Kiarostami in an interview with Dr. Jamsheed Akrami

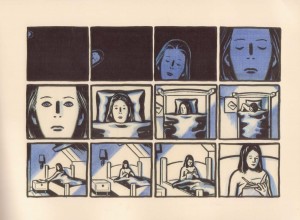

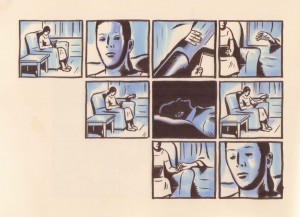

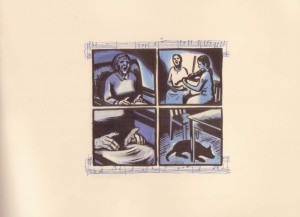

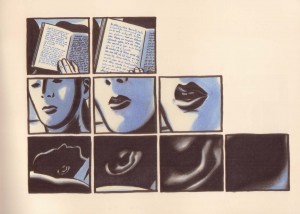

A dreamer awakes and starts scribbling in a journal by her bedside.

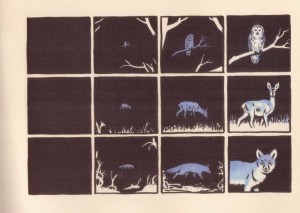

Then darkness…

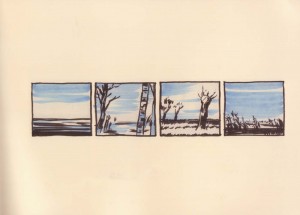

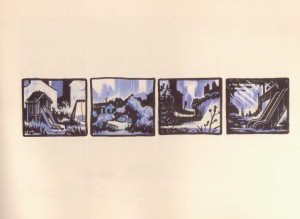

….forest and marshland. The panels hold the horizon line and come four at a time.

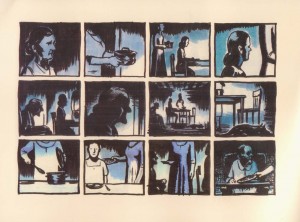

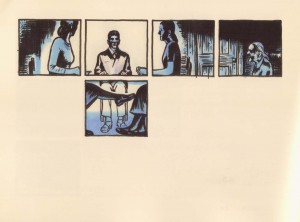

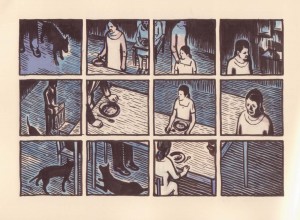

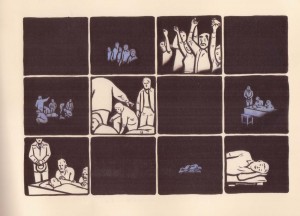

A house is lost within that wood and holds three women. They are of varying years, like the Fates of old, and are sitting down to a meal together.

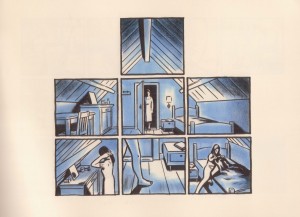

A visitor arrives by night and is given a meal before he is taken to an upper room by the youngest woman.

He is given a bed to sleep in. Then the curtains are drawn and the woman sits by his bedside reading. It is not a place of cohabitation but a place where stories are told and conceived.

The words and the images they evoke flicker through his mind. Then, the night is over, and he has left the storyteller slumbering and drained in an armchair by his bed. There is a small fee left for her and the woman and her companions seem largely satisfied. The tale closes with a fitful passage into a collapsed city of dead appliances, silent street lamps, abandoned playgrounds and overgrown malls.

This story can be found in the latest volume of Eiland, an anthology containing the work of Dutch experimental cartoonists Stefan van Dinther and Tobias Tycho Schalken. It’s easy to get lost in its pages; flipping through it and sifting over the imagery without any real comprehension. This is, perhaps, one way to appreciate it; in a kind of dream state like the young girl who rotates into view at the start of Schalken’s story, dutifully scribbling notes into her bedside dream journal. It’s only prerequisite for comprehension is that the reader retreat, slow down and absorb.

In Schalken’s story, dreams are remembered, songs sung and old paths reimagined. This is a visual history which contains indecipherable words and nothing in the way of captions or word balloons; it is as silent as the medium it is produced in. The direction and punctuation lie in its plan and composition.

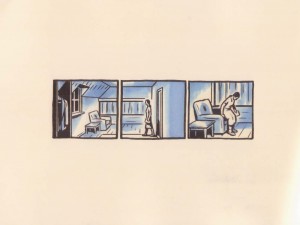

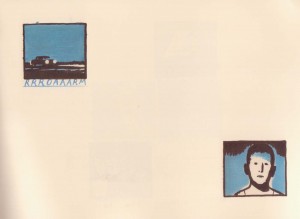

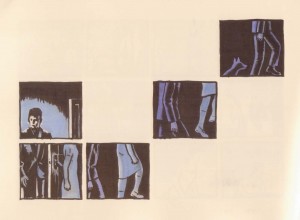

The layouts of Schalken’s comic are essential to our understanding of the proceedings denoting, at their most basic level, isolation [1]…

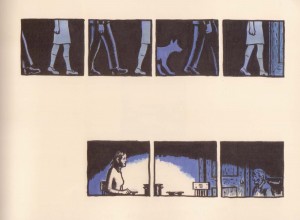

…distance…

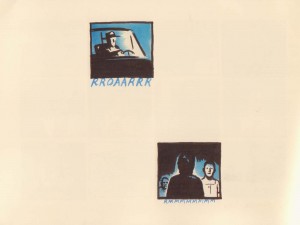

…centers of interest…

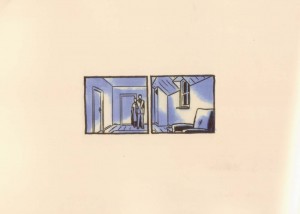

…and architectural space.

Their saturation of the page suggest moments of concentration or skillful dissections of time and space, our eyes being led horizontally and then vertically through the panels.

The black spaces which appear intermittently throughout act like points of origin, first moving us into the marshland, then pushing us back in time as we see the traveler being led into an upper room by the young girl, a process hidden from us 6 pages and an entire day earlier.

Next it presages a point where the story seemingly branches chronologically. It is a moment earlier (or perhaps later) in the story, and the women are in song.

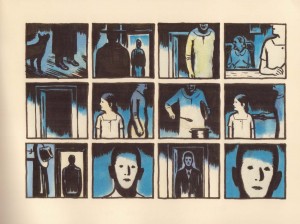

The man, that future caller, is barely imagined, yet the spatial proximity of these disparate timelines (interwoven on alternate pages) suggest a lulling of the traveler.

The dreamer approaches her place of rest and the storyteller begins her tale by the traveler’s bedside.

They are, logically speaking and within the framework of the story, one and the same person; separated in time but conjoined and connected in the facing pages, pushing us from dark inscrutability into the light of revelation.

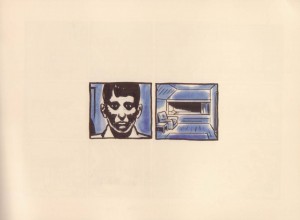

The traveler approaches his muse (this unassuming Clotho) with a sense of dread, as if he was approaching something arcane or even his very death.

Yet he receives the words as gratefully as he did the food earlier in the night, his auricle burnished by the artist’s brush…

…as was his mouth a few pages earlier during dinner.

And then there is the moment of departure.

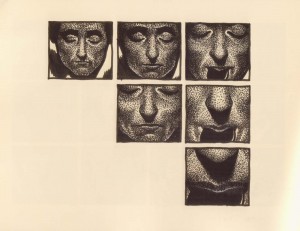

Like a flickering reverie, harsh light is shone unwaveringly but only for a moment on the animals and humans who line the road home; revealing puzzlement, love, conversation, celebration, chaos, death and slumber; faces – startled, cold, satisfied, young, old, sagging, balding, vibrant, bemused.

The man is returning to the harsh wasteland he calls home.

But this, too, is an act of storytelling, the shifting fantasy and half-heard mystery reproduced in the mind of the dreamer who is resting just above the strangely conversing couple.

[The storyteller begins her tale]

[The dreamer conceives her story]

She drifts between certainty and ambiguity; overhearing, mishearing and recording every sound that breaks through her fitful sleep, a strange facsimile of the oral tradition; still present when civilizations have grown old and people have forgotten how to speak.

________________________________________________

[1] Note how the panel depicting the house here nestles within the half-seen panels of the next page. Schalken is known to use the transparency of the printed page for visual effect.

I fear you’ll hate me for saying this…but it almost seems like an alternate-universe high-art Sandman story in some ways, with the focus on dreaming and story-telling.

I really like his use of space, something you don’t see a ton of in comics in that way.

Yes, but there are quite a few stories out there beholden to dreaming and story-telling. Gaiman acknowledges as much with his 1001 Nights-like story. And then there are things like the Earthsea novels which don’t make a big deal of it even if these concepts are an important part of the plot. It’s just an integral part of the creative process. Dreaming is not a big deal in the short story by Schalken as well but it does occur at 2-3 points in the comic.

Just curious, what’s your impression of the Earthsea novels – do you find them better than the Sandman comics or just about the same?

Oh, absolutely. I wasn’t saying they were indebted to Gaiman; more that it was just what popped into my head.

I love the Earthsea books. I’ve read them within the past few years and I still love them (at least the first three…her return to the series was not necessarily a good idea.)

Why is it better than Sandman? Let me count the ways…there’s none of the technical mess that comes because of the sporadic Sandman art; Le Guin has a lovely ear for language (“And their voices were one voice.”) She’s got a much better sense of character, I think; as I said in that roundtable, Gaiman always fudges on motivations and character interactions, which I don’t think is the case for Le Guin at all. And, maybe the most important thing, she’s a lot more brutal and creepy; the first chapter in the Earthsea books where Ged accidentally casts a spell on the goats and then comes running into town crying with all their eyes on him is scarier than anything in Sandman by a long bit — the ridiculous Dr. Dee spree seems pathetic in comparison. And that last book, with all the magic of the world leaking out and the dragons losing their speech and feasting on one another, and the dry land over the wall…man those are fantastic books.

There are downsides; her Jungian schtick is painful, and she can be a little too PC for her own good (criplingly so in the revisit.) But overall they manage to be really smart and at the same time to have the intensity and inevitability of a dream or a myth. One of the absolute best fantasy series out there, and I think Le Guin’s high point (though I like the Dispossessed and the Lathe of Heaven a lot too.)

Thanks for bringing them up. It’s fun to think about them again.

I vaguely remembered you mentioning Earthsea favorably in some comments but wasn’t sure. I read the novels quite recently as well and have to agree that the latter two (Tehanu and The Other Wind) don’t add much to the quality of the series. Tenar was a more interesting character in The Tombs of Atuan, and the way in which she was dropped in The Furthest Shore was pretty glaring to me. The correction and feminist-inspired deepening Le Guin attempted in Tehanu didn’t work for me.

Does Gaiman really fudge on character motivations? How so? Isn’t that just intentional space and ambiguity to let the reader in. I can’t say I found myself particularly creeped out by Earthsea, definitely not by the goat scene. The part where she describes prisoners having their tongues cut off before interrogation is pretty brutal for a “children’s” book. Isn’t her Jungian shtick really a Taoist shtick? It’s really spread on thick in the trilogy. I’m fine with that but it loses some of the mysticism inherent in Taoist beliefs in my opinion. What PC aspects did you dislike?

For the PC I may be reacting to the last two books. Just rereading the first one last night actually. There’s some nonsense about evil marauding white people, but it’s fairly subtle, and what the hell. I can’t really kick about that.

I found Earthsea absolutely terrifying when I read it as a kid, and I still definitely see that in it.

What about it is Taoist?

I love that 12 panel page of the people sitting down at the table.

The latest Eiland has been on my list of comics to get from overseas. If only the list weren’t so long.

Noah: A lot of the “ethics” in Earthsea are pretty Taoist in nature: the “equilibrium”, what finally happens to Ged. The resolution of the first novel is especially Taoist.

From the interviews I’ve read, the racial aspects of Earthsea are pretty important to Le Guin. She was pretty unhappy with what they did to Ged and Tenar in the TV mini-series for example.

Derik: The story above is only a small part of the latest Eiland. It’s there most substantial collection yet.

Yes, she’s very interested in racial politics. Which is actually interesting and I’m being overly cranky about it. It’s much less ham-fisted than what she does in “The Word for World is Forest.” I’m just cranky about it because of the last (fifth) book, which was awful.

I guess the balance stuff just seems too prevalent/familiar to be tied to a particular belief system for me. The thing I liked most about the last book was the insistence on the importance of death, and the way she presented death as being necessary for magic or life. It’s just very vividly done, and the vision of what happens without death (the dragons eating dragons, especially, or the healer who lost her magic and had to be renamed) is very powerful, I thought. Is that part of Taoism particularly?

Is there a name for the syndrome of the creator who just doesn’t know when to stop?

Look at the later Dune novels of Frank Herbert: a train wreck.

Look at Uderzo’s horrible solo Asterix albums.

Albert, you’re one of the richest men in France– retire, already!

Situate ‘The Word for World is Forest’ in its time, and it’s far more powerful; I read it when it came out and the Vietnam war was raging… and science-fiction was much more oriented towards Heinlein’s ‘Star Troopers’.

I didn’t hate “Word for World”; it’s definitely effectively painful, and obviously she’s a lefty and I’m a lefty so I’m on board to some degree. But it pushes the noble savage thing way past the breaking point. Pretending that the people colonized are morally superior to the people colonizing is just a bad move for everybody. Imperialism is bad because it causes suffering and death and injustice, not because the people being colonized are better than you or I.

There is a name for the syndrome of the creator who just doesn’t know when to stop. It’s called “Jumping the shark.”

I don’t know…at the end, one of the aliens remarks that he’s received ‘the gift of killing’.

I think ‘Forest’ is probably a subler story than you remember.

It’s certainly incredibly powerful, even today.

We should do a Le Guin roundtable! Maybe I could get Matt Thorn to contribute; he loves her.

Have to do The Wire roundtable first, though….

Noah: “Is that part of Taoism particularly?”

I don’t think it is but you’ll have to ask a proper Taoist for the answer to that question. My impression is that the Taoist aspects are strongest in A Wizard of Earthsea but she quickly embraces a more traditionally antagonistic relationship between good and evil in the other novels. You could still interpret the actions of Ged and Tenar as being demonstrative of “Wu Wei” though. The porous nature of sleep, dreams and reality is probably an echo of Zhuang Zi and the butterfly.

Did you watch the Ghibli “Tales from Earthsea” movie? Pretty bad.

Le Guin roundtable? Sign me up!

I’d be up for it! I love the first three Earthsea books (pretend that the other two don’t exist, actually) and “Forest”. Tombs of Atuan is probably on my top ten of all time list, should such a list actually exist.

I did not see the televised Earthsea. It sounded horrible.

Pingback: Tweets that mention Tobias Tycho Schalken’s Folklore « The Hooded Utilitarian -- Topsy.com

/ eh scrammel jakes

jpeg bath as an afro-deez[nuts]-ee-ak [Billy Joel: ak-ak-ak

tramelling as an arts praxis