I had no involvement in the selection of this year’s Best Online Comics Criticism. And I don’t plan to talk directly about the list here. Except to point out that it is fatally flawed. Because I’m not on it, damn it.

I did think I’d take this opportunity, though, to talk about two of my own favorite pieces of comics criticism from last year.

__________

Shaenon Garrity, Shaenon Garrity, “All The Comics in the World: Cathy,” Comixology, August 26, 2010

I’ve always cordially hated Cathy. Or at least, I’ve hated it when I’ve thought anything about it. I remember reading it as a kid in the funny pages on Sundays and finding it viscerally boring and ugly. I don’t think I ever in my life laughed at a Cathy strip. For that matter, I don’t know that I can remember virtually anything about a single Cathy strip I’ve ever seen. They all blurred together into the same bland multi-color blob that contained Blondie, Beetle Bailey, Hagar the Horrible — all those hackneyed, interchangeable soulless sub-sit-com mediocrities and their dreary punch-lines. A beneficent God would have canceled them all before I was born. A beneficent God would cancel them now. Who on earth ever liked them in the first place?

Well, Cathy finally did end this year. And in her eulogy for the strip, Shaenon Garrity answers my question for this one strip at least.

After decades of mainstream popularity, Cathy is still widely disliked by pop-cult elites like you and me. It whirls eternally between the Scylla and Charybdis of gender essentialism: men don’t like it because it’s about girly stuff, and feminist women don’t like it because it’s about girly stuff. Anti-feminists don’t have reason to like it either, what with the single-career-woman heroine who’s always been as open as newspaper syndication will allow about her casual sex life. That leaves just one demographic: women who are all for liberation and being your own woman and all that, but can’t quite figure out how to reconcile it with their actual lives. Women who never stopped feeling the pressure to cook like Betty Crocker and look like Donna Reed, and just added to it the pressure to change the world like Gloria Steinem. In other words, almost every woman of the Baby Boom generation.

That paragraph captures a lot of what I admire in Shaenon’s writing. Her points are clear and quick; put out there with such breezy ease that you can miss how much thought is going on. The note about Cathy’s casual sex life in the middle of the paragraph is a toss off, but it’s a doozy; it certainly never occurred to me to think of Cathy as a precursor to Sex in the City. Similarly, I love the way the reference to Scylla and Charybdis at the opening mirrors the references to Betty Crocker, Donna Reed, and Gloria Steinem on the bottom, turning iconic feminist heroes into ancient Greek hurdles. And, of course, it’s always nice to see oneself mentioned. “pop cult elites…men don’t like it because it’s about girly stuff” — hey! That’s me!

Shaenon doesn’t convince me to like Cathy — I don’t think anyone could do that. But in explaining her own (somewhat ambivalent) affection for it, she does manage to explain to me why I don’t like it. For example, Shaenon points out that Guisewite’s lousy art isn’t an accident; but part of her Boomer aesthetic, putting personal expression above craft. Shaenon links that particular kind of self-indulgent, principled shittiness to Doonesbury — thus helping to explain why I hate that strip too.

Ultimately, though, while I appreciate the insight into my own animosities, what really made this perhaps my favorite piece of the year was the insight into Shaenon’s affections. Not her affection for “Cathy” — rereading the piece I realize that it’s actually quite difficult to tell exactly how Shaenon feels about the strip. She explains with great acuity why the strip was appreciated by toits fans, but she never quite comes out and says that she is among them.

Yet the piece is filled with affection, and indeed love. That love is directed precisely at Cathy’s fans; the Baby Boomer women. Among those women is Shaenon’s mother…and Cathy Guisewite herself. Which is why I think my favorite line of the piece is this one:

“For my mother, who adored any man on television who could make her laugh, the image of the great Carson listening raptly to Guisewite, chin in his hand, was indelible.”

As is generally the case with Shaenon, it’s not flashy…but that’s a poignantly intimate description of her mom. And the sketch of Guisewite — it’s not just Shaenon’s mom who finds that image indelible, right? It’s Shaenon herself who finds it indelible, precisely because her mom does. Guisewite let her mom know that woman could be funny and sexy and indelible — sexy and indelible because they were funny — and that lesson is on Shaenon learned as well. And Shaenon’s love for Guisewite, and for her mother, is tied up in the fact that that’s a lesson they passed on to her.

I don’t imagine most women of my generation identify with Cathy. If we have a voice in comics, it’s probably among the chatter of webcartoonists, in autobio and semi-autobio cartoonists like Danielle Corsetto, Meredith Gran, Erika Moen, Lucy Knisley. They all draw more beautifully than Guisewite ever did, but maybe that’s just because my generation never challenged that pressure to be perfect. They don’t say, “Aack,” but that’s because we cuss. They’re not on The Tonight Show, but what the hell, it’s still pretty glamorous to be a cartoonist. Maybe our mothers understand.

_______________________________________

Matt Seneca, “Your Monday Panel 39,” Death to the Universe, November 29, 2010

I’ve talked about Matt Seneca’s writing once before. As I indicated in that piece, he’s somebody whose criticism I’m ambivalent about. On the one hand, he’s a huge, huge, fan of comics in wayswhich makes it difficult for me to share his perspective, since I hate comics (and everything else too. But mostly comics.) On the other hand, he’s a wonderful writer and a fascinating critic, who often makes unexpected leaps and isn’t afraid to make a bizarre theoretical pronouncement or twelve.

Matt writes faster than I can read, but the piece of his I did read and most enjoyed from last year is, I think, his discussion of a single panel from Rob Liefield’s “X-Force #1”.

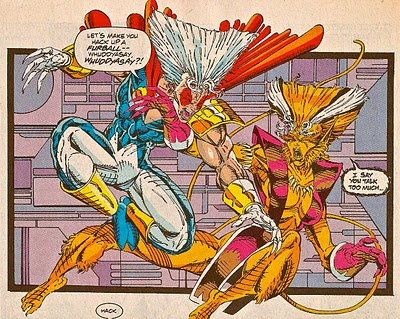

In case you’re unaware, to those who care about such things, Liefield is one of the most loathed mainstream artists in comics. His drafting skills are terrible; his design sense is aggressively crass and messy, his storytelling is…well, also crass and messy. You can see many of the problems on display in this panel here. The superpowers of the woman on the right appear to be (a) giant enormous hairdo, and (b) various limbs three times as long as they should be. The guy on the left also has an enormous hairdo, but his other superpower is the less impressive cape-made-out-of-an-accordion. Both of them are arranged in front of a Mondrian-meets-Jack-Kirby-but-uglier test pattern, and the composition in front of that is a splatter mess; it looks like Liefield threw ink at the panel and then arranged his figures so as best to cover over the blob.

Matt acknowledges all of that — and he thinks it’s awesome.

.. Liefeld was self-taught and snot-nosed, didn’t know or care what supposedly essential elements his panels were missing, what supposedly extraneous bits he was adding in, why it shouldn’t by rights have worked. And it didn’t matter a bit, because work it did — commercially, to the tune of more issues than had ever been sold before or have since, and aesthetically, as bizarre, confrontational, visionary comics. There’s precious, precious little of anything with even a remote connection to reality in this picture: the anatomy is shot to hell, the rules of gravity are awol, the figures and faces betray no connection to the human and only vague relation to the humanoid. But it’s all so self-consistent, all so true to the continuum of mind and hand and eye behind it. Liefeld sees muscles where people don’t have them, but always in the same places. He imagines hairstyles that boggle the mind, and he uses his trademark wavering, bleedy masses of little lines to sculpt them. He draws facial expressions that only intense plastic surgery could create in our world, but the surgeon is always the same. He creates superhero costumes that edge into abstract ideology, so “functional” that they’re no longer functional at all, pure eye-gouging adornment for the deformed demigods that tangle with each other like a sinewy yin-yang across this thick-bordered box. It’s a vision of a world further from the humdrum reality that superhero comics are supposed to free us from than anything else the genre has ever given us. Pure, fully formed, perfection unto itself.

This is the level Liefeld functions best on: abstract art. The crosshatching is ridiculous if you insist on it being some kind of representational device, but look at it for what it really is, lines on paper made by a hand that didn’t want to stop making them until every centimeter of space was shouting at maximum volume, and you’re getting somewhere. There’s a joy in the pure marks of Liefeld’s line-blizzards, something most every “Image style” adherent since has missed. A sugared up, perpetual-motion glow. It gets into the background of this panel too, where the raw naturalism of the hatchmarks’ asymmetry is dropped for a Jim Steranko spread of geometrics: the shape-and-line toolbox of superhero technology spread across the page in minute, functionless detail. There’s a significant aspect of the baroque to that background, so laden with stuff that it vies with the figures themselves for attention. Like the hatching, it’s purposeless, but it takes the picture further with enthusiasm, sheer steroided muscle, the delight its creator takes in the task of making it and then making more. And through all the glorious indulgence, Liefeld displays enough working knowledge of the action-comics mechanism to pop the characters out of their frame, increasing the bang of the image while ensuring that no matter how busy the background gets we’ll see what matters first.

There’s a lot of lovely description there; the “line-blizzards” the “sugared-up, perpetual-motion glow.” I think the best moment, though, is “sheer steroided muscle.” “Steroided”, of course, is a neologism, and an ugly, unnecessary one at that. But it’s ugly and unnecessary in exactly the way that Liefield’s drawings are ugly and unnecessary — lumpy, over-charged, bursting hideously from proper form in a gauche spray of cancerous adrenalin.

Matt’s piece, then, is not just a plea for Liefield — it’s a plea for a certain kind of comics, and a certain kind of comics criticism. Matt loves comics for their comicness, which means both for their pulpiness and for their existence as lines on paper. In the comments on the post, Matt notes that he is less fond of Liefield contemporaries like Jim Lee, who are able to draw more realistically and so have some more claim to being vaguely competent. And this makes sense — Matt doesn’t want comics to be competent by other standards. He wants comics which are nothing but comics; comics where the entire value is in the comicness. It’s not unlike the love that some critics bring to outsider art — the whole point is that it doesn’t look right. As Matt says, for him, Liefield is “visionary,” connected not to reality but to his own dream. And that’s Matt’s vision of comics, too, I think — a medium validated by its marginality. For Matt, folks like Suat who want comics to be part of, and judged alongside, the rest of the arts are elaborately missing the point.

As I’ve said before, I’m generally with Suat on this; I think the glorification of comics as comics (or of outsider art, for that matter) is problematic for all kinds of reasons. But…in this instance, the fact that I’m not a fan actually makes me appreciate Matt’s point more, I think. Matt begins his essay by noting that it’s very hard for comics fans to see Liefield art; he is so popular, and so despised, that his style turns people off instantly.

Look at it. I think it’s pretty great, and I’ll explain why in a second, but can you even see it straight? Or have the two decades since the comic it was published in sold four million copies so poisoned your eyes to liney, jumbled, hyperkinetic panels like this that something switches off in you the moment you perceive it? It’s a struggle for me too.

This doesn’t really happen to me. I mean, yes, I know who Liefield is, and I have generally not liked his stuff a lot. But I haven’t seen a lot of it, and really, I’ve hardly thought about him at all, because I haven’t cared enough to. This is probably the first time I’ve ever looked at a Liefield panel closely — and while I don’t think I love it the way Matt does, I can definitely see and enjoy the bizarre trashiness he’s grooving on. I don’t think I’ll seek Liefield comics out or anything, but the next time one comes my way I’ll be looking at it through the lens of Matt’s post.

So one of the things I liked about this post is that it changed my mind…and the reason it was able to change my mind was that I’m coming from a really different place than Matt. He writes things I’d never write, or even think about. So does Shaenon for that matter. Which is kind of a joy.

I am thrilled to see you discussing Shaenon Garrity’s Cathy piece here. I’ve raved about it myself, and I think the reason why is that it’s the perfect embodiment of everything I adore about Shaenon as a writer. She’s one of those writers who I would most often describe as “delightful” for all the reasons you mention in this post. Affection for something or another is nearly always present in her writing, and this, coupled with her glorious wit, are key to the personality that is evident in everything she writes. This is the kind of writer I *always* want to read, because not only does she have smart, insightful things to say, but she’s willing to say them in her own voice, without hiding behind either a curtain of formality or a curtain of defensive snark. She’s thoughtful *and* fearless, a rare combination in my experience.

Huh. OK, I admit it, I had to look twice to figure out which one was the woman in the Rob art. His figures are so damn lumpy that I flinch reflectively and reach for my pencil to correct them. I like the color, but man, does that anatomy bug me.

I haven’t seen much of his stuff, but yuck. The 80s hair band hair is cool, though. And the panel in the background. I’m not oversaturated with Rob, I’m just…I think I care too much about the human figure. *shudders* *peers through my fingers* No, still awful.

Ha!

What do you think of medieval painting, VM? I kind of love the way that stuff completely fucks with the human figure and perspective; it’s creepy and beautiful (at least to me.) That’s a bit of the appeal of outsider art too; the shock of seeing a world that doesn’t work. I don’t find the Liefield as sublime as the best of that, but I can appreciate where Matt is coming from.

In both of these, I definitely like the essays more than the things they are praising…

Melinda, I think I disagree with you about the formality and the snark. I don’t think those necessarily hide a true voice; it seems to me that they can be a resource for a writer, just like Shaenon’s informality or her wit. And while affection and love are things I respond to in writing, I like righteous anger as well.

Basically, I love Shaenon’s writing…but I wouldn’t want everyone to write that way! Variety is good.

Matt’s article could also work as a kind of Oulipo experiment. That’s the way I read it anyway.

Okay, I googled Oulipo, and I still don’t know what the hell you’re talking about. Explicate please.

Medieval painting gives me a headache (not in a metaphorical way). I find some of it very beautiful and very disturbing, but it always looks like a world gone wrong. It feels like horror to me, as a genre, even when it’s obviously trying to be something else. I enjoy the fiber arts more (tapestries, e.g.).

OTOH, I can look at Egyptian art all day long. That has a rhythm and structure that’s very….I don’t know. It feels right, even though people’s arms can’t move that way in real life, nor do they have crocodiles for heads, heh.

Noah, I appreciate many different styles of writing as well, and the world would be a terrible place if everyone wrote the same! But Shaenon’s style is one that delights me personally more than most, and this seemed like the time to say so. It’s my own taste, no more, no less.

I’ll retract my statement on formality and snark. Again, that’s really just my personal taste, as I tend not to enjoy either very often. Anger, on the other hand, is a completely different thing, which I associate with neither.

“But Shaenon’s style is one that delights me personally more than most”

Well, we agree on the most important bit!

Medieval painting– I love it, love it, love it. Not out of the snotty purism of Ruskin and the Pre-Raphaelites, but because for some reason it seems to connect so directly to life, like a live electric wire. Look at the ‘Très Riches Heures de Jean, Duc de Berry’:

http://vivre-au-moyen-age.over-blog.com/album-1045928.html

Though I still find it disturbing how they depicted scenes of dismemberment and torture with such utter bored placidity on the faces of both victimisers and victims…

So, it’s time for the pro- Liefeld backlash?

Why not? His stuff has a kind of purity to it. It makes no pretense to be what it isn’t.

Months and months after writing that column, it only just occurred to me that I should have mentioned that my mother’s name is Kathy.

No, no; I think it’s better as a late-breaking revelation….

Also, thank you for all the very kind words. For the record, I’m fond of Cathy (mainly for Guisewite’s dialogue, especially the stuff sending up 1980s consumer-speak), but I really love Doonesbury and medieval art. I just spent a day at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, in the room where they keep the Cezannes and elsewhere, and I felt a little bad that Western artists ever invented perspective. There’s something absorbing about that flat-but-deep look in paintings from the very early Renaissance, just before the development of geometric perspective.

I also enjoy medieval artists’ love of visual symbolism and their inability to draw babies.

OMG!! The babies!

It really is horror movie-esque; the hideous deformed Christ children and their bizarrely malformed mothers…I can’t get enough of that stuff….

Noah, maybe that’s a missed demographic for comics publishers, all of the fans of hideously deformed Christ children and their bizarrely malformed mothers. Sounds like a hit comic soon to be a major motion picture to me!

I always liked Cathy… I think it’s because nearly every other comic in the Sunday section is about marriage or parenthood + the wacky things that kids (or pets) get up to. I never saw myself as even a potential wife or parent or pet owner. I like Cathy, Dilbert, Doonesbury: the comics about single people; and Peanuts, Calvin & Hobbes, Foxtrot: the comics about kids from the kids’ perspectives.

Note to self: start praising shitty comics, fast!…

Wait…you don’t like Cathy, Domingos? You don’t like Rob Liefield?

I am shocked, sir. Shocked to my core.

Domingos, you mean you don’t?

I bet you are but, above all, let me tell you that I despise Lynn Johnston’s saccharine.

No I don’t, Bill, everybody knows that…

I hate For Better or Worse too; even more than Cathy, I think, which I really, really hate.

But…you can have great criticism about bad comics. And vice versa!

I would love, looove, for you to write about For Better or For Worse, Domingos. Best yet, could you write a piece that only addresses positives about the strip? I think that would be a real winner.

Bill, Noah and Sean: I was half joking!…

That said, the serious part is really two parts: (1) Noah: of course and I liked Shaenon’s article (even if I don’t exactly buy that “Cathy” as self expression bit – I think that Matt Seneca’s text is a bunch of nonsense, though), but there’s an effect of, how can I put it?, glue? If the writer isn’t careful the mediocre subject matter gets glued to the great writing. (2) You nailed it Sean: it looks gimmicky: pick a mediocre subject matter (you get extra points if it is mediocre *and* popular) and surprise your readers by intelligently praising it. It’s a lot of baloney, but people just love to be surprised.

This is the sort of thing that would kick off a 50 page thread on the tcj message board with death threats, isn’t it?

I don’t think it’s gimmicky; I mean, I don’t doubt that Shaenon and Matt are genuinely taken with what they’re writing about. Tastes really do differ. And I just don’t agree that mediocre subject matter drags down a piece, nor that great art elevates it. Lord knows there’s plenty of bad writing about masterpieces.

Domingos, I was all joking! But I will give you five bucks if you can write a coherent essay about Lynn Johnston AND Robert Altmann.

Roberto Altmann, that is. No need to sit through Nashville again.

Well, it might be a gimmick, but it’s an underexplored gimmick.

I’ll chip in five bucks as well- dead serious. We’re up to ten. And I second the Robert Altman inclusion.

I’d also be willing to trade you a relentlessly positive essay on a topic of your choosing, should you desire such a thing more than a five dollar bill.

The most surprising thing about Matt’s essay for me is that it forced me to look at something that I had long since been incapable of seeing as an actual image. For a boy of twelve in 1992, Rob Liefeld’s style was ubiquitous- copies everywhere. I have so many pages of Liefeld burned into my poor brain that I don’t think I’ve ever really looked at one of his panels and been capable of seeing it as solely a visual. You don’t have to agree with his conclusions to see that as a valuable insight.

Hmmm… Tempting, tempting! 10 bucks, no less!…

How about an essay about Roberto Altman and Robert Altman as the Thompson and Thomson? I could mimick the usual formalistic praise of Hergé… I bet that Bienvenu Mbutu Mondondo would love it.

Noah: “And I just don’t agree that mediocre subject matter drags down a piece”

That’s not what I said. It’s the opposite: a great piece (and Shaenon’s qualifies) pulls the art up if the writer isn’t careful. This is a problem in academia, but people know in there that, usually, academic criticism isn’t evaluative.

Pingback: I Wish I Wrote That!

Ah…I didn’t understand you, Domingos. You’re worried the essay will cast a glamour on the crap, not that the crap will pull down the glamour (wait a minute…that metaphor didn’t work. Oh well…onward….)

Alex, That’s fascinating about the medieval art. I dislike it because it feels so unreal to me. Huh. But the plants in the tapestries always feel connected to life.

Those babies are so creepy. So. creepy!

Well, I grew up in a New York neighborhood right near the Cloisters…used to go there all the time and fell in love with the Unicorn Tapestry…

Alex & Vom, I think part of what works so well about viewing medieval art at the Cloisters (I used to live up there too, Alex) is that the environment so matches the art. I think that makes it feel much more real than it could in any other setting.

Agreed, Melinda!

(For those who don’t know what the heck we’re talking about:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Cloisters)

One wonderful thing the Rockefellers did– they wanted the view from the Cloisters to remain beautiful– so they bought up three or four miles of New Jersey forested waterfront, and donated them to the state for a park.

It’s great to be a billionaire!

My late father told me about the countless times he’d take business documents to the Cloisters and work there in beauty and peace…myself, I more than once brought my homework there.

Melinda, though, you must think of the context in which I live– in France.

The apex of medieval beauty is still alive here.

I’ve seen the cathedrals of Notre-Dame de Paris, of Chartres, of Rheims, of Beauvais, of Quimper, of Saint-Denis…

So rare to have a spiritual experience coincide with an aesthetic one! The only appropriate word is “awe”.

Vom, I hope one day you’ll have this epiphany…come to France, and I’ll be your willing guide!