More than thirty years ago, Frederik Schodt began laying the ground work for a book that would become the first real information in English on the phenomenon of Japanese comics- Manga! Manga! the World of Japanese Comics. It’s rare that a seminal work should be the most comprehensive as well—and yet, twenty-eight years after its initial publication, it remains the best historical survey of manga available in English. I first encountered the book almost eighteen years ago, on a crammed shelf at the downtown Orlando library. At the time it seemed like a portal to an alien world, full of glimpses into exotic styles and genres and storytelling techniques. Two decades since that first encounter, I thought I’d take a look back at the book and interview its creator, with an eye on what’s changed since its initial publication.

The original release of the book must have been a bittersweet event to fans of Japanese pop culture, for although it gave a peek into the world of Japanese comics, it was a series of fleeting glimpses at best. Here in the book is an entire world, a tremendous publishing phenomenon, thoroughly described and dissected, an entire history and culture springing to life through clear prose and lavishly illustrated pages. And yet what is a synopsis compared to the comics themselves? What type of frustration might this theoretical fan have experienced in reading about these exotic comics which, short of learning Japanese, would forever be inaccessible to her?

Thirty years on, for this particular reader, it’s a very similar experience.

For all the changes in the industry, for all the expanding audience and changing tastes and thousands of titles currently available, it’s still a drop in the bucket. The majority of works discussed in Manga! Manga!, and in fact many of the genres represented, are still not available in English. Of course, as Fred Schodt reminded me when I spoke to him last week , “the industry,” meaning any type of meaningful manga releases in English, didn’t exist at all at the time he was writing. Virtually nothing was available.

Some genres discussed in Manga! Manga! might be too far removed culturally from most North American or European readers to really engage with. Some of the more exotic descriptions in the book focus on the genres of salary man manga, pachinko manga, or mah jong manga. One incredible sidebar is given over to a description of the truly berserk-sounding Jigoku Majan, or Mah Jong Hell, about a vicious mah jong player who, “when he learns that he was conceived not through love but through artificial insemination” begins “to hate society.” Suffice it to say that much chaos and pathos ensues, including tears, sex, attempted murder by bow and arrow, crying, death by falling, suicide by arrow, wolves, and lots and lots of dangerous mah jong action.

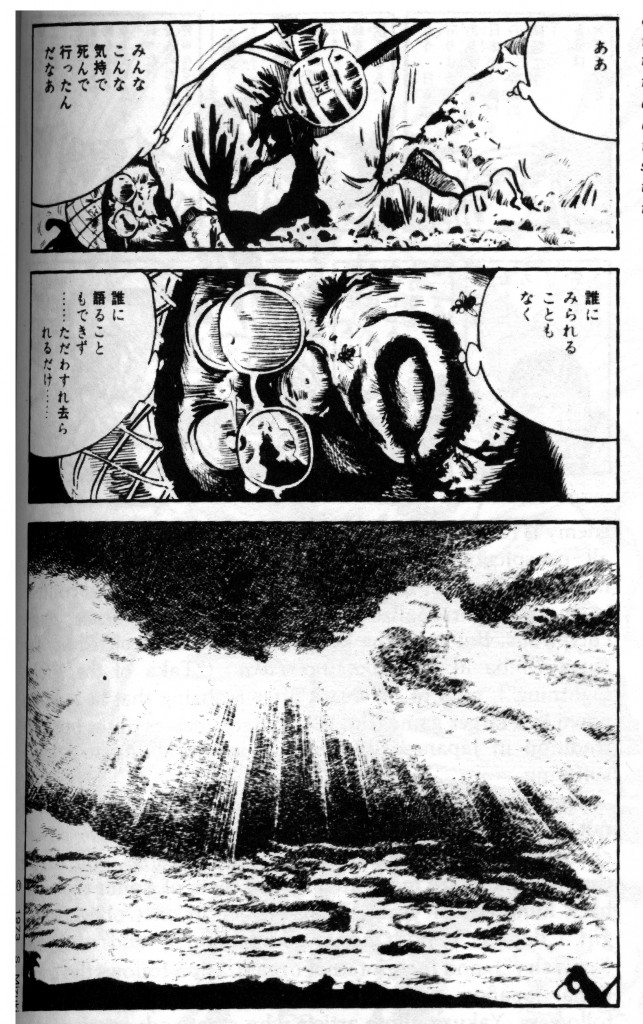

One of the more intriguing areas that Schodt touches on is the war comics of the sixties and seventies. Schodt points out that Japan is “the only major nation in the world today to have a clause in its constitution renouncing war forever, and forbidding the maintenance of land, sea or air forces.” As a result, rather than reveling or romanticizing war itself, many of the Japanese war comics Schodt describes instead revel in the glory and horror of death, in the bonds of friendship, the beauty of the hardware, and “the ability to endure suffering.”

Schodt offers a single page and an intriguing description of a 1973 work entitled Banzai Charge, a 350 page story by Shigeru Mizuki , a one-armed cartoonist whose war time experiences, including the loss of his dominant hand, informed his life work. Set during World War II, Banzai Charge follows a squadron of Japanese soldiers who are ordered on a suicide mission against a group of American soldiers. Some manage to survive, but, as Schodt describes it, they’re informed that “since their glorious death has already been reported they must either commit suicide or attack again.” Schodt reproduces a single page from the work, and it’s wonderful: cinematic but highly stylized, grotesque but not lurid. “Ah, so this is how everyone went….” Schodt translates for Maruyama, the main character and the last to die. “…unseen … and unable to speak to anyone… only to be forgotten.” The page is beautiful and compelling, and stands as a fragment of a body of work completely unavailable in English.

Another cartoonist that appears in the discussion of war comics is Leiji Matsumoto, best known in the States for contributing character designs and series concepts to the anime series Star Blazers, but a seminal manga creator in Japan. Although Viz has made a few half-hearted stabs at releasing some of his science fiction work in English, in Japan he is also known for his Senjo (“Battlefield”) series of military-themed short stories, and his break-out slice of life comedy I am a Man. Schodt says that the latter stars “a student without a university who lived in a tiny apartment, owned sixty-four pairs of striped boxer shorts, and subsisted on a diet of instant noodles and mushrooms that he grew in the closet.” Matsumoto is also one of four artist who is represented in Manga! Manga! by a full twenty four page story, in his case a tale of the last days of an ace pilot cast away on a South Pacific island.

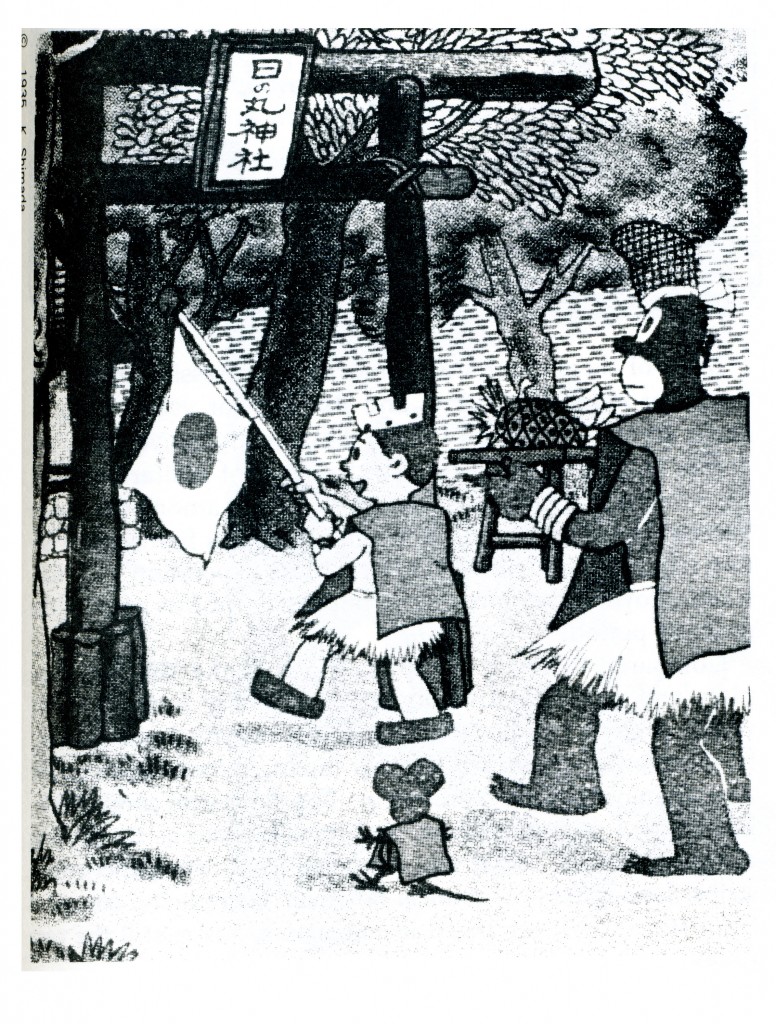

Fans of more stylized cartooning might appreciate the glimpses into the pre-war, pre-Tezuka manga culture, represented by such titles as Boken Dankichi Gekiga enthusiasts will find several intriguing descriptions and illustrations as well, including much discussion of the more obscure work of Kamui creator Sampei Shirato. I could continue listing all of these unopened doors, but at some point it might be better to just refer you to the book itself.

It’s possible that the fragmentary nature of the experience, of seeing only a few panels and a brief description of these stories, in some way works in their favor, or at least works to push my enthusiasm and anticipation of these works past the point that any comics could reasonably sustain. Let’s say that tomorrow some enterprising publisher were to release Banzai Charge, or Shirato’s Baccos, or another work by one of the other cartoonists I’ve been discussing. Is there any way the reality of such a work could be as great as my imaginings of it? Much like the “Black Paintings” of Goya or the poetry of Sappho, the incomplete nature and the possibility for speculation means that the possibilities are almost by definition greater than any potential actuality. I look at the single page of Banzai Charge, or the single panel of I am a Man, and the full works themselves are as good as my imagination can make them—they are any combination that can fit the known information. They are potential only, and that potential itself is tantalizing in a way that the actual works can’t ever be.

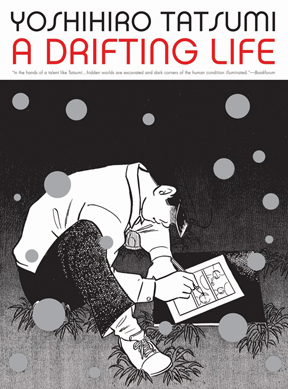

Translation itself can function like this, in a certain way. Rather than being a definitive text, it’s always a version of some hidden or unrealized ideal, and as a result it’s easier to convince myself that the flaws are a by-product of the process itself. Awkward dialogue can be overly literal wording—some lack in the aesthetic experience can be a result of the printing, or panel shuffling, or flipping, or paper quality. Some works themselves are aided by this open-ended quality, specifically Yoshihiro Tatsumi’s A Drifting Life, which derives a considerable amount of its power from the quotes and references to the gekiga work of the artists he is discussing. How would the book change were those works themselves be available in English? Certainly the sequences depicting Tatsumi at work on Black Blizzard have lost some of their appeal for me having now read the source work itself.

Some of these thoughts were already buzzing in my head when I called Fred Schodt up last week at his home in San Francisco. He was kind enough to take some time out of his writing schedule to answer some rather fannish questions, and to indulge me with a little bit of prediction as well.

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

SMR: When you were first writing Manga! Manga!, was your intention advocacy of some type, or were you trying to just give a survey of the phenomenon?

FS: I wanted people to pay more attention to Japanese popular culture in general, and what was being done with comics in Japan was so interesting and so little known and so important that I really did feel motivated. It took a huge amount of time to write it—running around and interviewing people and all kinds of things. So I was totally dedicated to my cause, which was making people aware of this very interesting phenomenon that was being overlooked. And it wasn’t just comics, actually. I felt there was way too much emphasis put on Japanese traditional art and business techniques. There really wasn’t much attention being given to how vibrant Japanese popular culture was. The impressions of most people were that Japanese were these very staid, robot-like salary men, or Zen monks or something like that. It was such a disconnect from what I saw, and that actually was a big motivator. I was quite inspired by a book by Robert Whiting called The Chrysanthemum and the Bat. He did a good job taking baseball as a way of introducing a little-known aspect of Japan. And I really liked that book. Even though my book is totally different from what he created, what he was trying to do something very similar, which was to show people that there was much more to Japan than was being written about generally. The disconnect was so huge that it was important that people started to fill in the gap between what Japanese were perceived as and what they were really like. But of course the main driver was I just loved manga and I just loved comics. But there was this other thing as well. I felt like I was on a bit of a mission.

SMR: I saw an interview that you gave right after the release of Dreamland Japan [1996] where you were discussing the market at the time, and you referenced how most of the releases then were primarily science fiction and fantasy manga. Were you taken aback when publishing started to branch out?

FS: When Manga! Manga! first came out there were almost no translations of any kind. Most of them were kind of vanity projects that were initiated by artists in Japan. The English was very fractured, and they were very limited one-shot kind of projects. So by the time Dreamland Japan came out things had already changed quite a lot. By 1996 Viz was at work and Japanese comics had a foothold in America. Initially I was really surprised by the success of shojo manga. It really took the whole industry by surprise. For a while people were thinking that shojo manga were going to save the whole publishing industry. <laughter> When I wrote Manga! Manga! I didn’t think that Japanese comics were ever going to be as popular as they’ve become in the States. To me it’s really a symptom of the fact that there’s this kind of global mind-meld going on among young people. If you’re talking about the industrialized, informationalized first-world nations, a global youth culture has emerged. As a result people are living in a very similar world, and they can relate to a lot more about other cultures than they could have twenty or thirty years ago. It’s a big change.

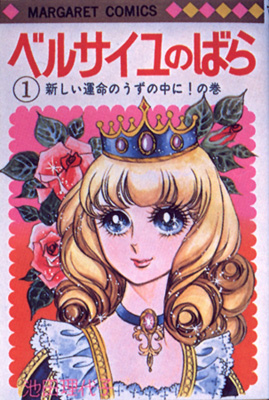

SMR: In the back of Manga! Manga! you printed about 100 pages of comics by four different artists. [a chapter of Phoenix by Osamu Tezuka, “Ghost Warrior” by Leiji Matsumoto, and a chapter apiece from Rose of Versailles by Riyoko Ikeda and Barefoot Gen by Keiji Nakazawa] It’s interesting to look back on it now to see which of these artists have been published further in English, and when. Of course, Phoenix took a tremendous amount of time to be published here, but it was successful when it finally was, at least critically, if not financially.

FS: At least critically. <laughter>

SMR: And of course, there’s Barefoot Gen, which came out almost immediately. And you were involved in that project. Whereas there’s been no Rose of Versailles and almost no Leiji Masumoto.

FS: Yeah, I’m surprised by that. I don’t know exactly why. With Rose of Versailles, it seems like there’d be a market for the series here, and I know there are fans, people that have devoted websites to it and that sort of thing. I don’t know what the situation is, whether it’s a rights problem or what. Leiji Matsumoto is kind of puzzling to me too, because I think a lot of his stuff is just fabulous. But what has been translated here has not caught fire in the way I thought it might have. I’ve always thought that his war series, and even the much more Japanese pop-culture oriented stuff, the four-and-a half mat tatami room, starving student kind of scene that he mined for many years, I thought that stuff was wonderful. Though I can understand why that might not come over here, because it’s intrinsically linked to a culture that doesn’t even exist in Japan anymore. But I would have thought that the war stories would have come over, because they were beautifully done.

SMR: I wonder how much of it just comes down to marketing.

FS: With his space stuff, with Starblazers and Harlock, it hasn’t really caught on the way other Japanese works have, which is kind of interesting. Because his space stuff does have an international aspect to it.

SMR: What do you think the likelihood is of sports manga catching on? I’m going to ask you to use your predictive powers here….

FS: I don’t see that really happening. But I’ve been wrong on so many things. It would be nice if it happened. Maybe people that are into sports here don’t read as many comics? I don’t know. But I’ve been mistaken regularly as far as what will become popular <laughter>. It’s fascinating to see how things have been developing.

SMR: It seems obvious from your new book <The Astroboy Essays: Osamu Tezuka, Mighty Atom, and the Manga/Anime Revolution> that you have a deep and abiding interest in Tezuka’s work. I was wondering if there’s a particular period or series that hasn’t been translated that you’d like to see.

FS: Of Tezuka’s work? Tezuka has been as widely translated as any artist. Of course, that doesn’t mean they’ve been commercially successful. But when you look at what Vertical’s put out, or DMP bringing out Swallowing the Earth… that really surprised me, because that’s a really obscure work even in Japan. He’s been translated more widely than I ever imagined. I guess I’d like to see the stuff that’s set in Japan more. Shumarie, and the one… I can’t remember what it’s called in English, but it’s about his ancestors.<Tezuka’s Ancestor Dr. Ryoan> It seems Vertical has taken it upon themselves to be the translator of Tezuka’s work. And that’s wonderful.

SMR: Did you get a chance to read A Drifting Life?

FS: Yeah, that was really a surprise. That’s an example of a Japanese artist that was really forgotten about in Japan. Drawn and Quarterly brought a lot more attention to Tatsumi. And then Japanese publishers picked up on him again, and he became the focus of more media attention in Japan, and won more awards. There are a couple of artists like that, who had more fans and critical attention overseas, and then they’re reevaluated in Japan. Shirow Masamune is another example. I think it’s safe to say that he had more fans in the United States before he became really big in Japan.

SMR: During the Appleseed period?

FS: Even Ghost in the Shell. That was one of the early Japanese works to really catch on in America, partly because of the sci-fi, dystopian near future, world that we can really relate to <laughter>. But I think Americans could really relate to it better at the time than your average Japanese reader. Of course, he’s big in Japan now, but my sense of it is that his career had a huge boost because of his popularity in America. And Tatsumi was relatively forgotten. I wrote an intro to Goodbye, one of his books for Drawn and Quarterly, and that was the main point I made—he didn’t even have a Japanese Wikipedia page at the time. That was the main thing that struck me when I wrote the forward to it— in Japan people barely know him but in America everyone’s raving about him!

SMR: I saw that you mention him in Manga! Manga! but it’s almost an aside, basically just mentioning him as the person who coined the term “gekiga.”

FS: Yeah, and that was kind of his place in history in Japan. Barely anyone was reading his work, and most of his work, until he was rediscovered this last couple of years, was regarded as “nekura,” or really dark. Almost too dark for the modern generation. People were not reading him much anymore. But now they are.

SMR: What would you like to see more of personally? Is there a particular genre that you think is neglected?

FS: No… American publishers have kind of dabbled in all kinds of things that they hope will work, and I think at this point if an American publisher thinks they can make money they would do anything. <laughter> But that stated, most of Japanese manga, and art too, are still too intrinsically linked to daily pop culture in Japan that is often different from here and won’t come over here. And that’s okay. We’re never going to see many pachinko stories of mah jong stories- that’s not part of American’s lives. It would be great to read those, but I don’t think a market for them is going to evolve.

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

If you haven’t yet purchased Manga! Manga!, I would that you do so.

Frederik Schodt is also the author of Dreamland Japan and The Astroboy Essays, and co-translator of Osamu Tezuka’s Phoenix series, as well as many other manga. You can read more about him at his website, jai2.com.

Last month I wrote a post about Mitsuru Adachi, manga localization and the problem of genre, which you can read here.

Pingback: Tweets that mention Manga! Manga! And then more Manga! « The Hooded Utilitarian -- Topsy.com

Pingback: Yaoi and taxes « MangaBlog

It’s always wonderful to hear more from Schodt! Thanks for doing the interview!

Jason-

Thank you for reading! It was a pleasure to talk to him, and to revisit the book, even if the lack of some of these comics in English is a little painful for me. By the way, your comic looks fabulous- love the line work and the super-dense pages. I’d be curious to know the size of your originals, and what size the eventual print destination might be…

Great.

Well done. =D

It’s nice to read such interview.

I’m not sure how I missed this, as it was announced last June, but Drawn and Quarterly will be releasing the Shigeru Mizuki work described above! http://www.drawnandquarterly.com/shopCatalogLong.php?st=art&art=a4cb61ca4344d4 Should be interesting. Here’s hoping they don’t go the cut-and-paste flopping route, and rather leave it left-to-right or do a full mirror-reverse on the artwork. Here’s also hoping, selfishly, that it lives up to my (quite hefty) expectations..