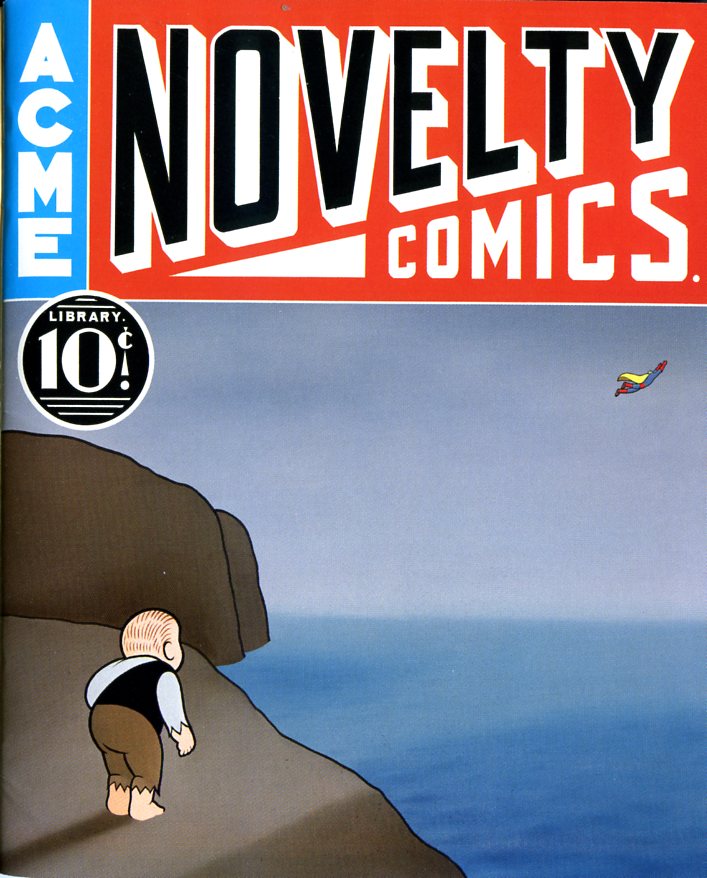

So can you guess? Who drew that?

Probably many of you know the answer. The clean perfection of it is a giveaway — but the fantasy touch, the almost flamboyant horror of it could maybe throw you off. The evocation of a too-brilliant gothic under some strange sun — this looks like it should be Herge, perhaps, not Chris Ware.

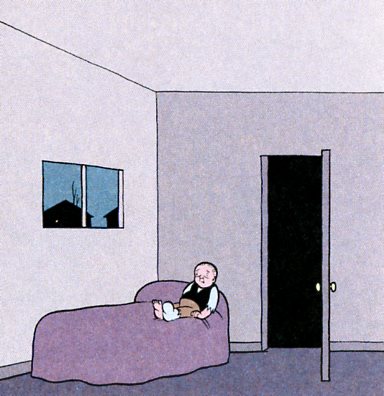

But Ware it is, from way back in Acme Novelty Library #10, before Jimmy was Jimmy Corrigan and before Ware had quite, quite decided that he wanted to become the poet of antiseptic blocks and middle-american repression. Those proclivities are there, of course, in the elegaic emptiness of Jimmy’s room:

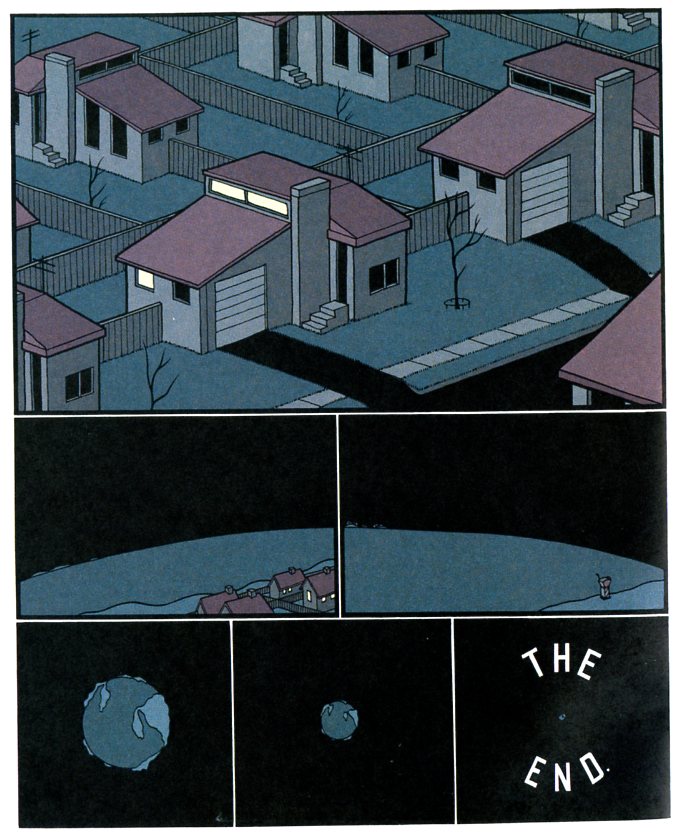

or of his town and world:

The cleanness here, though, is somewhat deceptive. It’s not the slack nothingness of ennui, but the overly perfect, charged landscape of surrealism. Ware’s later work often seems to fit most comfortably within literary fiction, but Acme #10 is closer to David Lynch…or even to Nightmare on Elm Street. Jimmy’s story is an Oedipal fever-dream; one of the few narratives to successfully meld superhero tropes with horror.

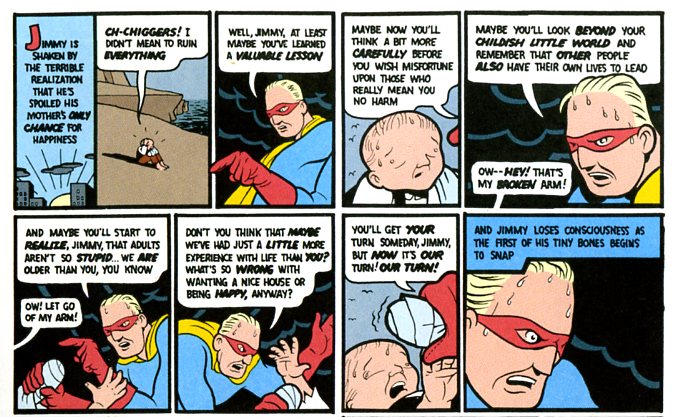

As in horror films, the plot is less a linear progression than a series of compulsive repetitions. Jimmy is repeatedly, sadistically betrayed and humiliated by father figures; his mother’s boyfriend, Nelson, and Superman. The reiteration of this trope starts out on a small scale — Nelson, playing with Jimmy, accidentally injures his arm. Soon, though, the pattern escalates:

Superman is both uberdad and castrating ogre; he’s the deranged and arbitrary law, sweating in his underwear, framed by ominous black clouds. The superhero is the monster; they’re not mirror images, but the same guy, the only father you get. Jimmy’s function, then, is to fail and be punished, over and over, for failing to live up to expectations and for trying to live up to them.

Ware’s even lines and bright colors, even the repetition of his perfect blocks, flatten anxiety and reality into a single seamless nightmare.

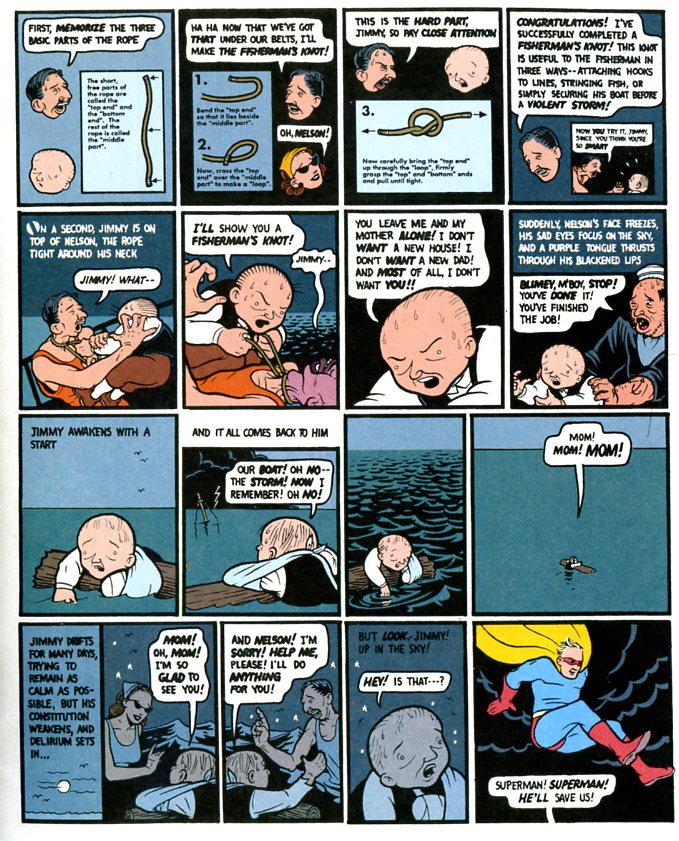

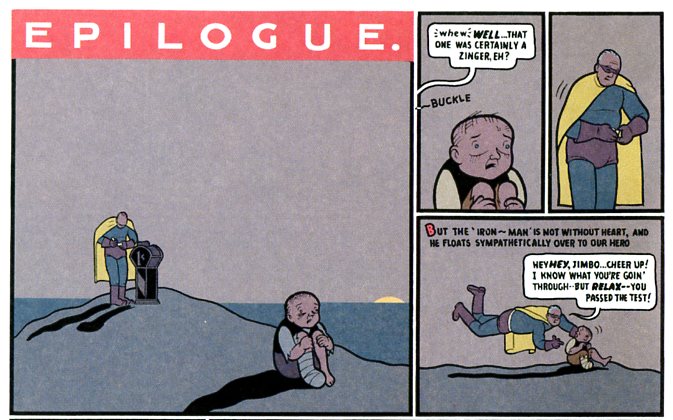

In this page, Ware starts out with a fun boy’s activity sequence. Jimmy’s head switches places with his mothers and then back again as Nelson describes the fisherman’s knot — starting with the three basic parts of the rope, a tripartite Oedipal snarl. Jimmy, goaded beyond endurance by Nelson’s condescension (forcing Jimmy in the fourth panel into a panel within a panel, dwindling into nothing) — does his Oedipal thing, and kills his (step father with the same rope. Punishment follows immediately; killing Nelson makes Jimmy an outcast, floating in nowhere, calling for the mother he was supposed to win and has instead lost. And then Superman appears to make everything better, or, rather worse. Again, the whole sequence — lesson, murder, punishment, Superman — slides one panel into another. I’m fairly sure Jimmy isn’t really supposed to have killed Nelson, and Superman does really show up, but the diegetic “reality” is less important than the fact that it all feels like it has the same oppressive weight. Symbols and dreams don’t so much blur together at sit up next to each other, each as hyper-real as the next, all pointing to the same overdetermined outcome:

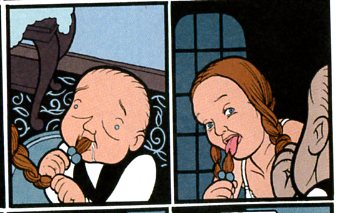

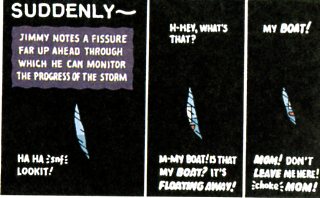

The first sequence there is a “dream” in which Jimmy imagines himself sucking on the hair of his (non-existent) sister. The second occurs a couple of pages later, when Jimmy is forced to watch through a slit in a cave wall as his boat (named Mom) sails away from the island on which Superman has left him. Shortly thereafter, Superman returns and reveals that the movie machine that Jimmy has spent his days and nights dreaming about, waiting for the moment when he might use his sole penny to watch it and relieve his boredom — that movie machine shows a pornographic film strip of Jimmy’s mother.

Jimmy is being punished, in other words, for the his desire, even if he won’t let himself know what that desire is. He wanted to see what was in that machine; he wants to reach through that slit in the wall, or suck his sister’s hair. He deserves what he gets; Superman is dispensing justice, just as he is supposed to.

The book, then, is shot through with compulsive sadism and perhaps even more compulsive masochism. It’s difficult even to know how the two could be separated. The whole point of the Oedipal triangle is that the son replaces the father, which means the son is the father, and so the castration of the son is ultimately performed by the son himself. Here, too, Superman is the father, but he’s also Jimmy — the childhood power fantasy. Superman sweating and declaring “we’re adults after all” — you don’t say that if you’re actually an adult and confident of it. Superman is Jimmy’s imaginary friend come to life, which means he’s Jimmy. And if he tortures Jimmy, it’s in part because Jimmy wants to be tortured — because he deserves to be punished, and because his torture is the way we (reader, author) identify with him and so enter the story.

Thus, the bitter pleasure when the comic’s narrative taunts Jimmy at various points:

That’s perhaps the most claustrophobic moment of this entire claustrophobic comic. The power fantasy becomes a fantasy of utter disempowerment; the adventure book expectations nail home the impotence.

This sequence, in particular, reminded me on this time through of Michael Haneke’s “Funny Games.” As with Ware, Haneke stacks the deck against his characters; his torturer is able to speak directly to the audience, somewhat as Ware’s (apparently complicit) narrator does. Like Ware, too, Haneke’s world is one of antiseptic bleakness. Particularly the scene immediately after the couple’s son has been killed, when the murderers leave the husband and wife alone in the empty house with the TV blaring — there’s a blank beauty there, an absolute devastation as the emptiness of the room becomes an unendurable weight.

Surely that’s what Ware is reaching for too in those sparse panels where Jimmy is isolated on one side, as if shoved to one side of the world.

“Funny Games”, though, compromises these moments precisely because they are moments. The perfect stillness should be there forever, but “Funny Games” has to go on, revving up its plot again and its series of more or less entertaining, and more or less tiresome, reversals. “Funny Games” is clever, but that cleverness often seems at war with the most striking aspects of his vision. (I think this is part of what Charles Reece is saying in this review.)

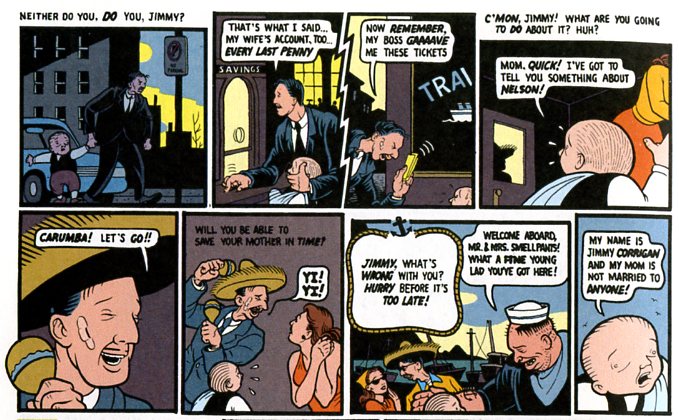

Ware is clever too. Consider, for example, this sequence again:

Notice we have Nelson stating “Every last penny!” two panels before we see Jimmy’s mom in what seems to be a state of semi-nudity, with Nelson waiting outside the door. On the island, Jimmy’s holds onto a sole penny in anticipation of looking in the movie machine…where, if he only knew, he could see his mother naked. The flickering recurrence of penny’s and nudity — or of father’s and arms…or indeed, the sadistic invention of Superman’s movie machine revelation — I’m sure Haneke would have liked to have come up with any of those.

The difference, though, I think, is precisely the way Ware divorces cause and effect. “Funny Games” is a game; it fits together like a puzzle. Acme #10 has puzzle-like aspects, but the pieces don’t actually go together — or at least not one after the other, in a sequence. Obviously you can read it straight through and you get a story of sorts. But there’s no satisfying resolution like, “everyone’s dead, start over.” Instead you’re left with images, themes, repetitions, blank spaces. Acme #10’s lack of narrative bloody-mindedness, the fact that Jimmy isn’t finished off, is why this isn’t really horror — and at the same time, perhaps, it’s the reason that it functions as a kind of distillation of horror. There’s no resolution here, no escape. He’s in hell — and not hell as metaphorical meaninglessness, but hell as intolerable meaning. Jimmy is always being punished, always deserving of punishment. He’s always on that island looking into that vulture’s beautiful, terrible maw.

___________________________

A couple days ago, Matthias Wivel said this in his reevaluation of Chris Ware’s Jimmy Corrigan.

There is a narcissistic aspect to it; the archetypical distillation of certain emotions inflicts the story with a crippling myopia that has consequences for its believability as a realistic narrative.

I would say that that’s right. And I would further say, in Acme #10, Ware got around this problem not by jettisoning the myopia, but rather by avoiding the realistic narrative. Acme #10 is narcissistic and monomaniacal as anything Ware has ever written. But that’s a strength, not a weakness, when you go for a cloistered dreamscape rather than for humanistic insight with occasional epiphany. Ware understands the inside of his own neurotic skull and he’s able, like Kafka, to give that interior the dread (and very funny) force of universal truth. Ware’s efforts to imagine real characters and real relationships, however, seem to me much less successful — and, ironically, much more solipsistic. I don’t follow Wareclosely anymore, but when I do check in, I only end up more convinced that Acme #10 will always be my favorite of his comics.

Lord, can we fucking banish Freud at last?

If ever there was a father deserving killing it was he.

Ah, Freud’s not so bad. Chris Ware took him and made this beautiful book. Surely he should get points for that.

And anyway you can’t kill him without taking his place….

Hm, sounds like a plan.

Yes, it’s a terrific story. It sort of channels some of the dissonant elements from the first third of the JC book. The rage, the repression, the bald-faced meanness. Who knows how the book would have looked had Ware decided to go with some of that instead of the crisp tone of disappointment and alienation that he went with.

Ack! I just realized the end of this post got cut off! Not sure anyone will care — maybe Matthias, since it’s a response to him…?

Oh great, yes, I’m actually trying to say something along the same lines in my piece — especially in the parts about Rusty Brown — though I obviously appreciate his conceptual structure and efforts at realism in Jimmy Corrigan a whole lot more than you.

I would say you appreciate them more than I do…though I’m not entirely immune. I quite enjoyed Jimmy Corrigan when it first came out.

Almost anything he does is lovely to look at (not those Branford Bee things maybe, and not some of the New Yorker covers, but for the most part….) And the way he slows down time is agonizing and beautiful…and not unKafkaesque either. I do feel like he abandoned his muse to some degree though, which makes me sad.