MELINDA: Hello, Utilitarians. I’m Melinda Beasi.

MICHELLE: And I’m Michelle Smith.

MELINDA: About a month ago, Noah asked if we’d be interested in having a conversation about comics here at The Hooded Utilitarian, similar to our weekly manga discussion column, Off the Shelf (at Manga Bookshelf), and our monthly art-talk feature, Let’s Get Visual (at Soliloquy in Blue). He suggested at the time that we might try discussing a mutually admired series (as we once did with Ai Yazawa’s Paradise Kiss), and that the subject need not be manga.

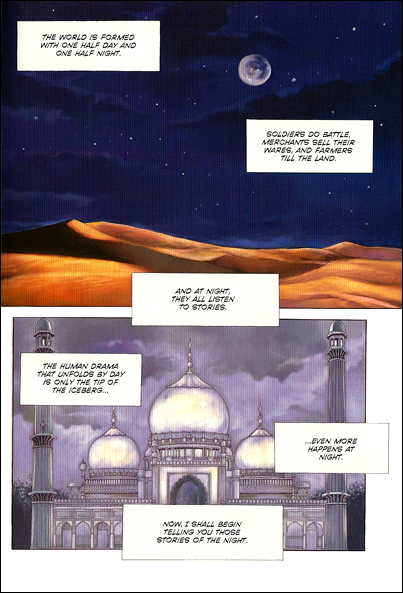

With those thoughts in mind, we decided to take a stab at One Thousand and One Nights, a South Korean boys’ love series written by Jeon JinSeok and illustrated by Han SeungHee, published in English by Ice Kunion/Yen Press. While this may seem like an unusual choice for this audience, there are a couple of things that make this series especially interesting to us.

First, though the story has a BL romance at its core, it is a multi-volume epic (11 volumes in total) featuring a series of interwoven stories-within-the-story drawn from multiple periods and cultural settings. Secondly, it’s a BL romance written by a man, unusual in a genre mainly written by (and for) women.

As you’ve probably guessed, this series is a loose adaptation of the original Arabian Nights, but with a male character in the role of “Scheherazade,” taking his sister’s place in the sultan’s harem of virgins to save her from their mad ruler’s nightly executions.

Michelle, since I’ve already talked about this series extensively in my own blog, would you like to continue with the introduction from here?

MICHELLE: As you said, the series starts with a twist in the gender department. Our setting is Baghdad, where Sultan Shahryar, once regarded as a hero by his people for his prowess in battle against Western Crusaders, has begun summoning young virgins to join his harem. At first this is seen as an honor, until it’s discovered that every girl is summarily executed the next morning. When Dunya, the sister of a translator named Sehara, is summoned, Sehara takes her place. After his true gender is quickly discovered, Sehara implores the sultan to allow him to tell a story and, when permitted, recounts the sad tale of a cruel princess nursing a wounded heart. The story is enough to convince Shahryar to spare Sehara’s life and appoint him his royal bard.

Having learned about Shahryar’s traumatic and tragic past from Jafar, the sultan’s oldest friend, Sehara has sympathy for the sultan and tries, through his stories, to show him the error of his ways and be a support to him. “He just needs to find peace of mind and return to his old self,” he comments at one point. “Then the kingdom will be happy as it was before.” Gradually, their friendship deepens, with Sehara’s tales and his forthright acceptance working day by day to heal Shahryar’s soul. Shahryar comes to depend on Sehara, who protects him from himself, and solicits a promise that Sehara will always remain by his side to protect him. Sehara agrees.

Alas, when political intrigue involving invading Crusaders and Shahryar’s scheming brother, Shazaman, puts Shahryar’s life in jeopardy, Sehara agrees to go to Jerusalem with the leader of the Crusaders on the condition that no one in the palace be harmed. This decision will lead to soul-crushing guilt when the conflict between the two brothers appears to result in Shahryar’s death.

How’s that?

MELINDA: I think that’s one of the most succinct and informative summaries of an eleven-volume series I’ve ever seen. Obviously this is the barest overview, but you get right to the real heart of the series, which is Sehara’s healing influence in Shahryar’s life, and how that influence extends to healing the kingdom as a whole.

Of course, something that’s very important to me as a reader is the fact that this process is slow, and Shahryar doesn’t get a free pass. The series’ creators, writer Jeon JinSeok and artist Han SeungHee, don’t shy away in the slightest from portraying Shahryar’s madness and brutality, nor do they ever let him off the hook for what he’s done. Shahryar pays and pays and pays for his sins against women, including his unfaithful queen. While in another kind of story, this might not be so crucial, in a series where we’re meant to root for someone like this as part of a romantic pairing, it’s important that his history of violence against women not be romanticized as well.

MICHELLE: You’re absolutely right. Even in the final volume, he’s still having nightmares about the deaths for which he feels responsible. It’s clear he’s never going to forget what he’s done, or even forgive himself for it, but he can begin to heal because of Sehara’s presence and ensure it never happens again.

Am I the only one who sees tremendous parallels between Shahryar and the Red King of Basara? For those unfamiliar with Basara, the Red King is initially introduced as a brutal villain, responsible for the execution of most of the heroine’s village, but through an extremely slow and therefore believable process, involving true love and the acquisition of wise new friends, realizes that his style of governance is all wrong and works to make amends. His subjects are slow to forgive him, but his transformation is genuine.

MELINDA: I hadn’t thought about it, but yes, I can see that parallel quite clearly. It’s interesting that you bring up Basara, actually, because I was struggling earlier today with making some general comparisons between Korean BL and Japanese BL, when really what this series (and several other long BL manhwa series I’ve read) compare to more easily in terms of Japanese manga is classic shoujo.

We’ve only seen a small amount of Korean BL in translation, so I can’t possibly ensure that any generalizations I might make about the genre as a whole are even remotely accurate, but just the fact that we’re having a conversation about a BL series that evokes comparisons to Basara speaks volumes about the differences between Korean and Japanese BL, at least what we’ve seen so far in English. In fact, this series has so much going on outside of its romantic trajectory, I wasn’t even comfortable referring to it as a BL series until somewhere around volume ten, because I actually wasn’t sure. Even Basara is more obvious as a romance early on than One Thousand and One Nights.

MICHELLE: I had the same experience regarding volume ten! It’s really quite subtle about their relationship in early days. I remember one scene in particular where it’s clear that something is going on, but I wasn’t sure if Shahryar was just teasing Sehara to get a response or if something physical had actually happened between them. It isn’t until the final volume that one receives unequivocal confirmation that, yes, they had slept together. Not that sleeping together means they’re having a romance. That definitely came later, which made the second time that much more meaningful.

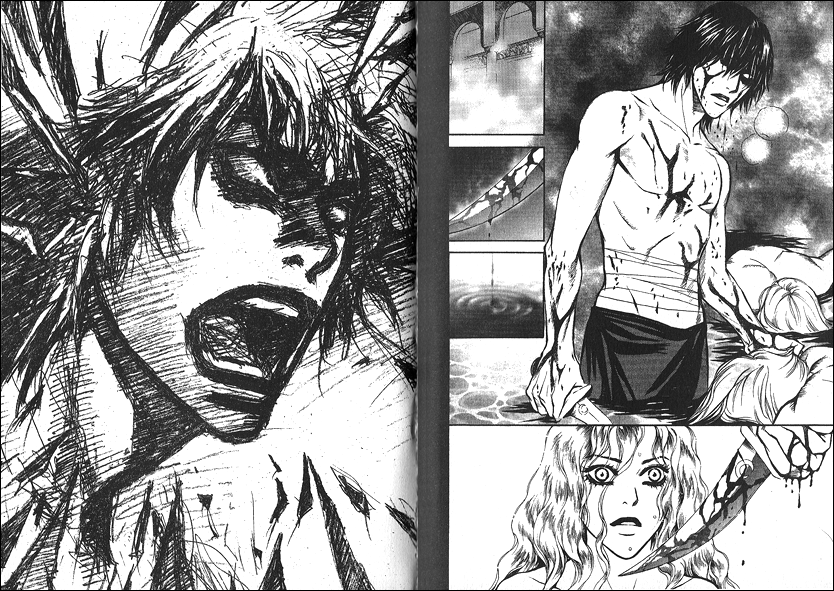

MELINDA: Now certainly one of the things that keeps One Thousand and One Nights from reading as straight-out romance is its stories-within-the story, which deserve an entire discussion of their own. But before we get into that, I just want to mention another aspect of this series that identifies it clearly as Korean for me (again, based only on what’s been made available in English), and that is its graphic depiction of violence. While Japanese BL (in my experience) is more likely to feature rape fantasy (particularly with a bigger, older aggressor and a frail, protesting partner), much of the Korean BL I’ve read contains genuine blood and gore, which, Wild Adapter notwithstanding, is less common in what I’ve seen of Japanese comics for girls.

This scene from the first volume of One Thousand and One Nights, for example, in which Sultan Shahryar discovers his wife’s infidelity, contains some of the series’ more brutal imagery. And I’m deliberately including the lead-up to Shahryar’s berserker-like breakdown to emphasize the shock of the page turn, which pretty effectively freaked me out the first time I read the series.

(click on images to enlarge)

The sequence continues with Shahryar and his wife, Fatima, confronting each other while drenched in a bath full of blood and dead bodies, lending an extra element of horror to what would be a pretty dramatic conversation in any scenario. You won’t be seeing this in Tea for Two, you know what I mean?

I’m not saying this is a good or bad thing, mind you. I’m just saying that it’s not out of line with we’ve learned to expect from Korean BL, based on what’s been translated. As violent as this scene is, after all, I’m not sure it can touch the raw brutality of, say, some of the early scenes in Let Dai.

MICHELLE: My exposure to Korean BL has been very limited thus far, though I am determined to read Let Dai and Totally Captivated in the near future. While I can’t exactly chime in with a knowing nod, therefore, I can at least agree that the feel is very different from the Japanese BL I’ve read. In the latter, I’m always happy if the author has bothered to construct a modicum of plot to accompany the romance. Here, the plot is fairly intricate and while it’s clear the romance is not at all an afterthought, it feels like it grows organically from the characters and events, if that makes sense.

While I did often like the stories Sehara tells, particularly when they’re used to communicate to Shahryar where he’s going wrong or to show the Crusaders’ commander that, kind as he may be, Sehara’s loyalties will forever lie elsewhere, I did also find them intrusive at times. In fact, my chief complaint about the series is that there simply wasn’t enough of Sehara and Shahryar together! Their big reunion in the final volume, for example, gets interrupted by a silly modern-day story in which the characters are recast as both students and avatars of Indian gods. Now, I grant that this is significant because it’s Shahryar telling this story, but what does it have to do with what’s going on with the main characters? Perhaps it’s simply showing how Sehara is more elegant in his narrative choices. I don’t know, but it bugged me all the same.

MELINDA: I loved that story! It was a little clumsy, but I thought that was part of the point. It didn’t feel at all out of place to me. I saw it as Shahryar’s way of both thanking Sehara for saving him from destroying his kingdom (as the god of destruction) and letting him know that he loved him, which I expect was a difficult point for him to bring up on his own. There were other stories I enjoyed less, but this one, I thought, was especially significant as part of the ongoing romance.

I have a feeling that this is an area where you and I actually may disagree overall, as I would say that I appreciated the stories-within-the-story at least as much (and maybe even more) than the more straightforward narrative. I was especially taken, for instance, with Sehara’s chosen retelling of The Romance of the Three Kingdoms, precisely because I thought it made Sehara’s point more gracefully (and artfully, perhaps?) than a direct confrontation with the western king might have.

Also, I admit, I just really enjoyed seeing Jeon JinSeok’s take on some of these stories, which, even including the two with modern-day settings, were all drawn from various bits of folklore and actual history. His passionate defense of Cleopatra and other historical (or mythological) women in the endnotes of volume three was really fascinating to me, and having that access to his thought process definitely influenced my reading of the stories as a whole. While I don’t think he was always completely successful at saying what he wanted to say through the stories themselves (the Socrates/Alcibiades tale is one he had some difficulty with, I think), I found myself increasingly interested in his efforts there.

The one story I thought I was going to really dislike was the one set during the US invasion of Iraq. It felt very out-of-the-blue to me when it turned up, and so far out of what I could accept as part of Sehara’s timeline that I originally dug into it with a very negative attitude. In the end, though, it may have moved me more than any other story in the series.

I wonder why our feelings about this are so dissimilar? Do you think we had different expectations going in?

MICHELLE: I don’t mean to suggest that I disliked the stories in general. Far from it. I especially like the more bittersweet tales—”Sometimes, the sad ending is more beautiful,” the author writes in the endnotes for volume two—like the stories of Turandot and Cleopatra, or the one about the possessive woodsman and his unfortunate wife, and you’re absolutely right that Sehara’s use of The Romance of the Three Kingdoms to explain his departure is downright elegant.

It’s just that where the stories crop up sometimes bugged me a little. Perhaps this is because I am more used to Japanese BL, with its focus on the relationship to the near exclusion of all else. Or maybe I’m just impatient. Regarding Shahryar’s story in the final volume, I can definitely see how its intent was to thank Sehara for preventing the destruction of the kingdom, but as a love confession, I didn’t find it particularly successful. Perhaps it’s only that Shahryar is clumsy at creating metaphors for falling in love, but I wasn’t as able to see the correlation between this tale and the actual plot as easily as I was for those told by Sehara.

MELINDA: To be fair, I do recall some half-joking remarks in my reviews of later volumes, in which I complained about them suffering from “Lack of Sehara,” so I think I must have experienced some of the same impatience you did, especially while waiting for each new volume to come out.

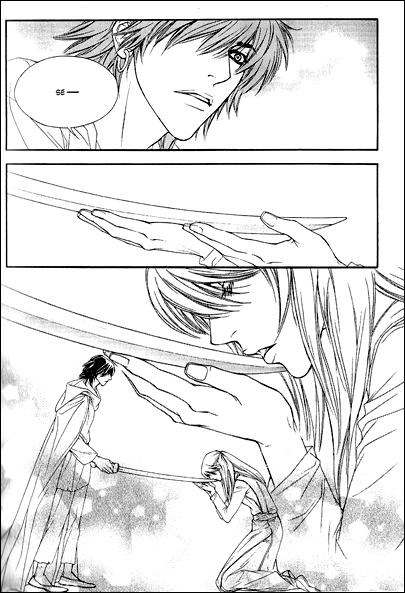

And lest you begin to think me unmoved by the series’ swoon-worthy romance, I’ll take this opportunity to prove otherwise. A perfect example of just how successful this series is as a romance is, I think, the unlikely success of this imagery.

This page is part of the scene in which Sehara leaves Shahryar to go with the Crusaders. He’s just had a conversation in English (unintelligible to Shahyrar) with King MacLeod, where he’s ensured the safety of everyone in the palace, and has informed Shahryar that he can’t tell him stories anymore.

The ultra-romantic, homoerotic imagery here is so incredibly blatant, such utterly over-the-top romantic cheese, it really should have just made me laugh. I mean, seriously, he’s kissing Shahrayr’s “sword”? Subtext that bold should not work at all, but I’ll be damned if, in context, it isn’t the most sincerely romantic thing I’ve ever seen. I should have laughed, but instead I just melted into a tiny puddle of goo. The skill required for Jeon and Han to pull that off between them is, frankly, extraordinary. These people should write romance for the rest of their lives.

MICHELLE: I can agree with you about that! And you’re right, while I could not possibly fail to notice the phallic symbolism at work, I still didn’t even crack a smile. Possibly the one image that really sticks with me, though, is what happens as a direct outgrowth of this scene.

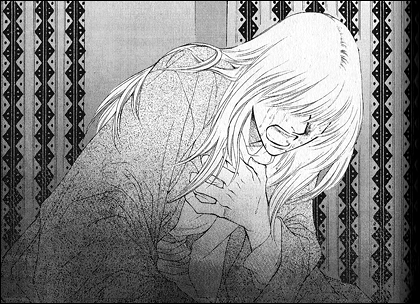

Sehara has previously promised to stay by Shahryar’s side to protect him and though his agreement with MacLeod was made with that aim in mind, it does take Sehara from Shahryar’s side at the time when he is most needed. The treacherous plans of Shahryar’s brother, Shazaman, come to fruition, resulting in Shahryar being suspected of collusion with the Crusaders.

Happily, Jafar—Shahryar’s right-hand man, who protects him from “sly politicians”—is able to prove the lie, but not before Shahryar escapes his confinement and has a violent encounter with Shazaman in the desert. When Shazaman returns without his brother, he is assumed dead and oh, that pose of heart-clenching grief when Sehara finds out. I love that we only get this one glimpse of his soul-crushing sorrow, because it’s completely sufficient to show the depths of his anguish all on its own.

MELINDA: Oh, yes! That really is one of the most effective images in the series. It stuck with me for days after I’d first read that volume.

MICHELLE: To me, that’s probably the most romantic image in the whole work, even above panels where they’re actually together!

Speaking of the encounter in the desert reminds me of another interesting element in the series, beyond its stories-within-a-story and romance—the unexplained. After discovering her infidelity, Shahryar banished his queen, Fatima, to the desert. It was generally assumed that she had died, but when Sehara catches a glimpse of someone who looks like her while delivering a letter to Shazaman’s palace at Samarkand, it seems possible that she is alive and actively engaged in scheming against her husband.

When Shahryar later faces similar perils in the desert, it initially appears as though Fatima appears before him to gloat over his predicament. She speaks to him for a time, then fades away, just as Jafar is discovering her mummified body kept behind armed guard by Shazaman. So, was that real? Was it some kind of visitation from beyond the grave, or was it a delusion? I would be inclined to side with delusion, but given the random deluge that turns up while the brothers are fighting in the desert, I’m inclined to think some kind of supernatural involvement is implied.

MELINDA: I’m glad you brought this up! I was assuming some kind of hallucination as well, but I’ll agree it feels like there is a bit more to it. It’s almost as though Shazaman’s insane delusion that Fatima’s corpse is still living has given it some kind of power to actually move her spirit within people’s minds and control their environment to some extent.

I have to say that one of the story’s more shocking developments for me, was the discovery that Shahryar is actually the sane brother.

MICHELLE: Ha! Yes, that was a surprise for me, too!

I really love how the writer handles Shazaman and Fatima. First, Fatima is made out to be a rather nasty person, and I admit I simply accepted this explanation at face value. And though I did think, when Jafar glimpsed her in the clutches of another man way back in volume one, “Hmm, that looks kind of like Shahryar’s brother,” I figured I must have been wrong when nothing came of it. When we later get her backstory, I was completely bowled over by it!

I had never expected to feel sympathy for Fatima, who is revealed to have if not a good reason for destroying Shahryar’s family, at least an understandable one for doing so. Shazaman, who always seemed like the more cool-headed brother, is similarly shown to have much hatred for his father and brother, stemming largely from their involvement in the death of his mother. The fact that he and Fatima conspire to drive Shahryar insane by reminding him how he brought about his mother’s demise (by notifying his father of her intent to run off with another man) is deliciously cruel. And yet, because they’re both dealing with so much pain it’s hard to hate them for it.

It’s like, you’re reading along, thinking the story is one thing, and then suddenly the curtain’s pulled back and you realize there was this hidden layer there all the time. I wonder what it was like rereading the series knowing this twist was coming. Were there clues you didn’t spot the first time around?

MELINDA: I wouldn’t say that I discovered a lot of hidden clues, though certainly it was enlightening to re-read the first volume with the full understanding of Fatima’s story. My view of her was, of course, much more sympathetic the second time around, but perhaps even more striking was a shift in my feelings towards Shahryar. He’s a fairly unsympathetic character in the beginning anyway, and this time around, it took me much longer to warm up to him, having more insight from the get-go into Fatima’s plight. While it’s difficult for me to summon a lot of sympathy for Shazaman, Fatima’s position as a woman despised in the palace (even by other women), running on nothing but a child’s vengeance, is not only sympathetic but also paints a bleakly honest portrait of life as a woman, especially a poor one, in the period of the story.

I think one of the things that surprised me most about this series when I first read it, is how much effort Jeon puts into inserting feminist commentary (or at least what he thinks of as feminist commentary) into the story. I don’t always agree with what he thinks works as feminism, but it’s obvious that it was really important to him to make these statements while writing a comic intended for girls. When I reviewed Let Dai (which is written by a woman), I made some mild (and pretty unpopular) accusations of misogyny–something I think is actually incredibly common in BL from any country–and I expected to find even more of it here. Not just because the author is a heterosexual man (though I’ll admit that was part of it), but because the story is set when it is, and even revolves around the romance of a tyrannical ruler who openly hates women.

Instead, I found myself engrossed in an epic BL series in which the author actually spends pages upon pages of his romance comic complaining about the plight of powerful women in history. He doesn’t do it perfectly by any means, but I found it personally gratifying.

MICHELLE: I recall something he wrote about Cleopatra that was along the lines of history accepting the achievements of women so long as they are homely, but if they happen to be beautiful, then it’s assumed that they were overrated schemers (wildly paraphrasing). Fatima’s story has echoes of this, too. It’s easy to buy that she’s manipulative and evil just for the fun of it because she recognizes that her looks give her power over men, but deep down, living like that gives her no satisfaction whatsoever. She’s clinging to revenge because it’s the only thing she has left.

I think what I will remember most about her is a remark she makes when being held by Shazaman, that that’s the only time she’s ever been happy in the arms of a man. She would much prefer to be loved, to have a family, but instead her looks are both blessing and curse. They’ve given her a means to survive and to exact her revenge, but they’ve also probably kept her in the path of lecherous men as opposed to those who would value her for something else.

MELINDA: Yes, I think that’s exactly the way he’s portraying Fatima. Another thing I appreciated in his notes was his confession that part of the reason why he included The Romance of the Three Kingdoms as part of the series, is that it’s a book that only boys in South Korea are typically encouraged to read, and he thought that was a shame. As with a lot of the stories he’s included (as well as much of his commentary on Islam and Christianity), I’m not familiar enough with the source material to know how faithfully he’s portrayed the original, but I do appreciate his motives.

Yet, with all this in mind, I don’t feel like he’s looking down on the genre he’s writing here, either. He’s enthusiastic about introducing his audience of girls to a 14th-century historical novel, but he’s no less enthusiastic about writing a modern BL romance series for them. Does that make sense?

MICHELLE: It makes complete sense. How often we are citing his endnotes! Compared to some creators, who use this space to talk about their latest video game purchases or the results of popularity polls, Jeon’s notes are always informative and interesting.

It occurs to me that we’ve talked about Fatima and Shazaman probably more than the lead couple. I think this is because Shahryar and Sehara have, when you get right down to it, a simple relationship. Their connection is bone-deep and sincere and I love them together immensely, but I find I haven’t as much to say about them as some members of the supporting cast. Maybe this is because they don’t have a lot of angst as a couple—Sehara’s concern that Shahryar has turned to him only because he distrusts women is swiftly dismissed—since most of the turmoil they endure is inflicted by outside sources.

Aside from those we’ve previously dwelt on, the series has four other significant supporting characters: Jafar, a trustworthy and lifelong friend of Shahryar who blames himself for not preventing his friend’s downward spiral into crazy; Maseru, Shahryar’s dark-skinned bodyguard who has the most adorable and sad subplot concerning a sheep that I have ever seen; Dunya, Sehara’s somewhat petulant sister; and Ali, a malcontent who was intending to propose to one of Shahryar’s victims before he got word that she’d been summoned to the palace. While Dunya and Ali serve their purposes in the story—the latter is particularly useful in obtaining evidence of Shazaman’s treachery—and Jafar’s integrity is largely responsible for things turning out well in the end, it’s the silent Maseru who steals my heart. I wish we’d learned more about him.

MELINDA: Maseru and his sheep! I think I loved Maseru and his sheep as much as any of the romance in this series, and I’m grateful to Jeon for not taking that to an unfortunate place, because y’know… he really loved that sheep.

I’d say that Dunya was a favorite of mine, actually. Yes, she’s petulant as you say, but she’s also pretty bold, and probably one of my favorite scenes in the series’ later volumes is one in which she fearlessly chews out Shayrar for letting himself be ruled by his emotional weaknesses instead of protecting Sehara. With Shayrar as a romantic lead, it’s easy to forget what that really means in this setting, but a young woman in 13th-century Persia is yelling at the sultan, something she, apparently, could be beaten or even executed for without question. That’s bold.

And while we’re talking about supporting characters, I feel like we’ve been treating the artist, Han SeungHee, as a kind of supporting character, with all the praise we’ve heaped on Jeon. Considering how beautifully she draws his story, and how many wordless pages there are over the course of the series, that seems profoundly unfair. As the member of the team with actual experience in girls’ comics, I would guess that she probably influenced the project tremendously, beyond just her visual contributions. Her influence doesn’t feel as obvious, and maybe that’s just because she spends her endnotes talking about walking her friend’s dog, while Jeon is going on about Confucianism in The Romance of the Three Kingdoms. But I’d say her work speaks for itself.

MICHELLE: Well, he kind of did take the Maseru/Sheep relationship to an unfortunate place, though not in the way I think you mean! In fact, perhaps I should be giving more credit to Han for the affecting, one-page scene in which Maseru returns to the stables after the Crusaders have been and gone and finds an ominous indication of the poor sheep’s fate.

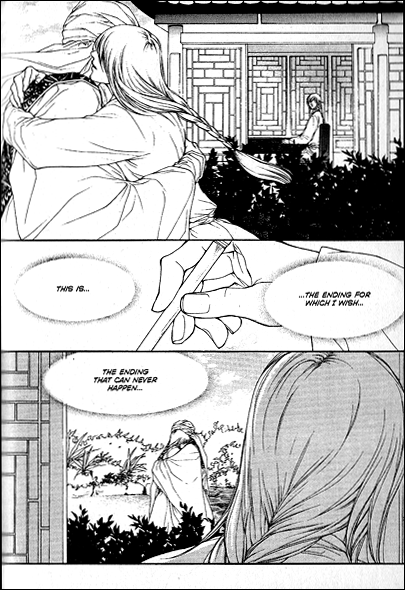

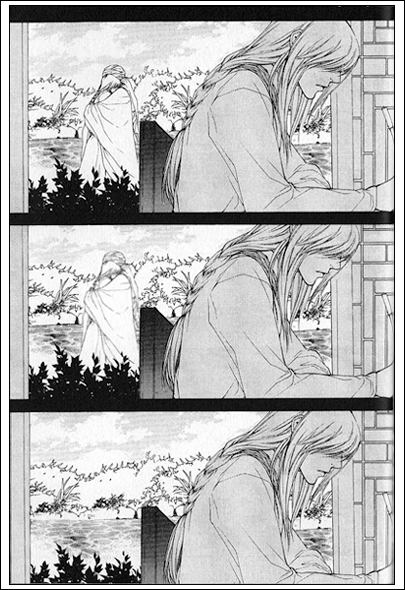

As you know, I am a huge fan of nonverbal storytelling, something Han is exceedingly good at. One particular scene sticks out in my memory. In volume eleven, Sehara has taken himself about as far from Baghdad and memories of grief as it’s possible to go, and is living with the merchant Zhao and his family in Beijing. There, he begins to write his and Shahryar’s story, in the hopes that it will help him move on, but he’s stuck on how to end it. LingLing, Zhao’s granddaughter, suggests that he write the ending he wishes would happen.

The next few pages depict his fantasy, in which a happy and healthy Shahryar calls his name and they share an embrace in the garden. The perspective now shifts to a solitary Sehara, sitting disheveled and immobile in his chair while the embracing figures in the garden beyond him slowly dissolve. I thought that was such a nice effect.

(click on images to enlarge)

MELINDA: Yes, I agree.

Speaking of Zhao, I will say that one of the things I do find unfortunate in the series is the kind of lecherous humor Jeon inserts via characters like Zhao. His behavior towards Sehara, played obviously for laughs, reminds me of all the reasons why I hate Eunuch Kong, Park SoHee’s leering “comic” figure in the popular series Goong. And it actually affects me more negatively here, I think, because I feel on some level it belittles Sehara’s sexuality by making a joke of it.

MICHELLE: I totally thought of Eunuch Kong every time Zhao put the creepy moves on Sehara. I didn’t see it as belittling Sehara’s sexuality, at least not intentionally, but I do have to wonder what is up with two otherwise exceedingly good series expending precious page space on a grotesque character like this! True, Zhao actually does more to affect the plot than Eunuch Kong, helping Shahryar to escape when he’s briefly held captive by Ali and his men in the second volume, but he was so icky otherwise I had to question why Sehara would willingly put himself within reach of the fellow again.

MELINDA: So, is there anything else you’d like to say about the series?

MICHELLE: It was very interesting reading One Thousand and One Nights while simultaneously reading and working on a roundtable on Akimi Yoshida’s Banana Fish. I know you’ve written before on the similarities between the central relationships in these series, but wow. Even though Shahryar’s personal journey might remind me of Basara‘s Red King, the way he interacts with and comes to depend on Sehara reminds me a lot of Ash and Eiji from Banana Fish. Sehara’s clear-eyed gaze, Shahryar’s tortured one… the way Sehara believes in Shahryar when no one else does, the way Shahryar can scarcely believe that someone considers him worthy of saving… I think pairings like this must immensely appeal to both of us!

MELINDA: Yes I think they really do. I do see a lot of Ash and Eiji in Shahryar and Sehara. I’ve heard that some people refer to Let Dai as “the Korean Banana Fish,” but aside from the gang aspect, I really don’t see that at all. One Thousand and One Nights, on the other hand, fits that description pretty well, at least in terms of its primary relationship.

I think what I appreciate most about this series is that it genuinely satisfies me as a romance fan, something that many BL series simply fail to do, while also satisfying me as a fan of effective visual storytelling.

Too many writers (and readers!) treat romance like it’s easy, and it’s really, really not. I’m not even sure where anyone got that idea, since it’s probably the thing that we humans as a whole have the most difficulty navigating in our own lives. There’s a reason why romantic love (or the lack thereof) is the driving force behind so many of our species’ most passionate acts–from works of art to heinous crimes. What other human obsession, besides money and religion, has inspired as much beauty and pain as the mystery of romantic love?

Sure, romantic fiction is fantasy, but the emotional journey has to feel real, or that fantasy falls apart. I don’t think good romance writers get enough credit.

MICHELLE: Well, I think a large part of the problem is that not everyone tries to make the emotional journey feel real, and when readers encounter those unrealistic, unsatisfying stories and are disappointed, it casts a shadow over the genre as a whole. I’m still waiting to read a romance novel that I really like (aside from Pride and Prejudice!); thank goodness I can find convincing and moving romance in manga and manhwa!

For more discussion with Melinda & Michelle, check out their regular features, Off the Shelf and Let’s Get Visual.

Pingback: One Thousand and One Nights at The Hooded Utilitarian | Soliloquy in Blue

“I’m still waiting to read a romance novel that I really like…”

Room With a View?

You’re discussion of misogyny in BL is interesting. I talked about that some in my series on Moto Hagio. who I think can be quite misogynist (that misogyny linked to her hatred of her mother and of herself.)

There’s maybe an interesting parallel with Heather Love’s “Feeling Backward,” which argues that homophobia, or hatred of gayness, has been at the center of a lot of gay literature — that self-loathing and sadness have historically constituted gay identity as much as self-assertion and celebration (I think that’s a fair summary of her thesis; it’s been a little while since I read it, so I may have garbled it.) That definitely works for Hagio…it’s a little weirder in BL, since women aren’t usually the focus…and of course here it’s a male writer, which may change things…..

I have a few romance novels I plan to recommend to Michelle too!

I feel like I’m always complaining about misogyny in BL, and I keep not understanding it, so I just go around in circles. Maybe I should read “Feeling Backward” and see if it helps me out.

I remember reading an LJ post from someone back in my slash fandom days, in which the OP talked about how het fanfic was really disgusting because it included icky girl parts (or something like that). I was appalled at the time, and I think I’ve never recovered. I get the attraction to homoerotic fiction (obviously, since I read it) but when that wanders into disgust with the female body, or a complete exclusion of female characters in positive roles, I feel that something’s gone horribly wrong.

Pingback: Manga Bookshelf | BL Bookrack on the road!

I heartily welcome recommendations for good romance novels!

I tried to read A Room with a View once as a teen, but didn’t get very far, due, I am sure, to my immaturity at the time. It’s definitely on my “to read” list. Perhaps it deserves to be bumped up.

Feeling Backwards is really, really good. Not sure it will address this issue quite, but it’s worth reading on its own merits.

This book:

Boys’ Love Manga: Essays on the Sexual Ambiguity and Cross-Cultural Fandom of the Genre; Antonia Levi, Mark McHarry and Dru Pagliassotti, eds.; McFarland; 280 pp., $39.95; ISBN: 9780786441952

that we did that tcj roundtable on has I think an essay on misogyny in BL….unfortunately I don’t remember it as being super enlightening…though maybe one of the better pieces in that book….

Yes; it’s an article by M.M. Blair about different portrayals of women in different yaoi series. The essay’s not bad.

I think my feelings about misogyny in BL are really part of a much larger discussion, ranging from the Twilight post I made here about women distancing themselves from other women, to the way hard-core Draco Malfoy fans justify hating Ginny Weasley for not being nice (seriously). It’s a thing.

Forster is pretty great, IMO. Jane Eyre’s really good too, though the romance is not unsquicky. And I love Trollope — A Small House at Allingham can be considered a great romance, I think. Georgette Heyer’s not bad either, though not great.

I recommend Charlotte Brontë in general, particularly Jane Eyre and Villette. I also really like Anne Brontë’s The Tenant of Wildfell Hall.

I’ve read Jane Eyre. And Wuthering Heights, too, which I always think of in the same breath, even though it’s by a different sister. (I need to read something by Anne!) I suppose I did like them, though it wasn’t a passionate love like I have for Austen’s works.

And because I love Austen, I feel very sure that I will love Trollope, who seems to share her wry style. I am very excited about reading something by him, but it’s just a matter of finding the time. When I got my Kindle at Christmas, I ported over a whole bunch of Trollope freebies from Project Gutenberg. :) I’m thinking of trying a one-shot like Orley Farm first.

Lastly, I’ve read two by Georgette Heyer, with varying results. The Masqueraders is silly and kind of meh, but I thought These Old Shades was fabulous fun, though that’s another one where the romance is not unsquicky. I’ll definitely be reading more by Heyer in future.

I think we must have exceedingly similar tastes in romantic fiction!

I plan to read Villette in the near future!

Michelle, I named my dog after Villette‘s heroine, Lucy Snowe, if you need any proof of how much I love that book!

Villette’s really sad though. Can it be a romance if they don’t live happily ever after?

I’ve only read one Heyer book, which I thought was okay…. I’d recommend starting with Barchester Towers for Trollope, or the Small House at Allingham. You really don’t need to read the other books in the series, and those are supposed to be his best (they’re both fantastic, I think. Though…I think Domingos expressed a hatred of all things Trollope. I might have hallucinated that though.)

His autobiography is great too.

I’m kind of anal about series, so I’d probably start at The Warden, but at least it’s really short. :)

And I like sad! I’ve just started Anna Karenina, which I hear fits that bill.

Villette is, at least, ambiguously sad. And yes, I still think that’s a romance! For me, the ambiguity of the ending reflects Charlotte’s unwillingness to trod fearlessly down the road of wish-fulfillment for herself, considering where she drew the romance from in the first place. I sort of wish she had, but less as a reader than as a fan of the author.

Don’t start with the Warden. It’s mediocre. Just move on to the better books….

DearAuthor.com has great romance reviews by literate and intelligent readers. Anything Janine recommends I’ve found to be especially good.

Thanks, Shelly!

Re: The Warden – Deciding to do that will require much taming of my anal-retentive sensibilities!

“I was struggling earlier today with making some general comparisons between Korean BL and Japanese BL, when really what this series (and several other long BL manhwa series I’ve read) compare to more easily in terms of Japanese manga is classic shoujo.” … “While Japanese BL (in my experience) is more likely to feature rape fantasy (particularly with a bigger, older aggressor and a frail, protesting partner), much of the Korean BL I’ve read contains genuine blood and gore, which, Wild Adapter notwithstanding, is less common in what I’ve seen of Japanese comics for girls.”

Regarding the differences between Japanese and Korean BL: I do agree that Korean BL tends a bit more to the type of old-school epic melodrama that was popular in Japanese BL in the 90s, but I think the main drivers of the difference in the material available in English are the context in which BL is published in the two countries, and the filters applied by US publishers.

First of all, Korea has few specialty BL magazines; most BL-type stories run in general girls’ magazines. Thus, commercially published Korean BL is usually more analogous to, say, Silver Diamond, than to the typical contents of Be x Boy or Gush! More sexually explicit material is usually confined to donginji / doujinshi, and less likely to see commercial publication (although some donginji series get picked up by publishers when they’re long enough for book format, like U Don’t Know Me). The Korean bedroom-politics stuff is out there in spades, it’s just in donginji, which is a format that is not appealing to licensors.

One Thousand and One Nightsand Let Dai both ran in the girls’ magazine Wink, which is a total melodrama-o-rama-factory, and I’m sure the house style had something to do with the amount of angst and violence. But Japanese BL also goes to the gritty blood-spattered end of the spectrum on a regular basis, it’s just that the US publishers have mostly given that material a wide berth. (I think part of the problem is that such stories tend to run in the more adult-oriented magazines and are consequently more sexually explicit and kinky than US publishers prefer.) DMP and Tokyopop have largely restricted themselves to the lighter, more teen-oriented, and more traditionally romantic works, so we don’t see many of the styles and types of Japanese BL that exist (in some cases this is a good thing; blind shopping landed me with a couple of gross-out comedy BL anthologies, which is apparently something popular enough to be its own subgenre, although I can’t imagine why…).

To summarize, the US market isn’t seeing the full spectrum of either the Japanese BL market or the Korean BL market, but the conditions of the two markets and the interests of licensors push the material we see from Japan more towards lightweight smutty romances and the material from Korea more towards intense but relatively chaste melodrama; Japanese gorefests and Korean smut don’t make it over. Or at least not legally.

JRBrown: It doesn’t surprise me at all to hear that, which I why I so heavily disclaimed all my comments in the piece. I actually tried to find out more about the Korean BL market beforehand, but came up pretty short, even after asking friends who are fluent in Korean & frequently read Korean-language comics blogs. So in the end, I went with the disclaimers.

I will mention, though, that one of my favorite Korean BL stories that has made it over here is U Don’t Know Me, which was in fact donginji and is pretty smutty. Still it has a really solid story & a one of the main characters is fearsome with a knife, so it fits in with the general conclusions I was able to draw overall.

Oh, duh, I just realize that you already mentioned U Don’t Know Me. I keep editing this comment–please forgive me!

Just to add: One of the things I like specifically about both U Don’t Know Me and Totally Captivated, is that even though they actually do feature smaller, blonder guys in what would be the uke role in Japanese BL and even feature some non-con with them as the, uh, receiving party, both of those guys are genuine tough guys, who have made it clear elsewhere in the story that they could seriously hurt their aggressors if they actually wanted to. I don’t want to say that this doesn’t happen in Japanese BL because as you point out, we’re getting filtered versions of this in English, but it is *really* welcome to me not to see a helpless little uke painfully struggling his way through forced sex. I’m assuming this, again, may be due to publisher choices. Is that so?

Michelle and Melinda are very welcome to this reader…but to what extent is HU going to be a BL-dominated blog?

We have Kinukitty, VM, and now M&M going on and on and on about BL comics and manga.

It has become obsessive.

This particular post was a worthwhile read, turning me onto a fascinating series. But are future M&M posts going to be exclusively BL?

I mean, that’s Kinukitty’s approach. She will not post anything that’s not yaoi.

Michelle Smith- And I like sad! I’ve just started Anna Karenina, which I hear fits that bill.

uhhh.. are you referring to Tolstoy or is there some “Anna Karenina” manga I’m not aware about? I wouldn’t consider the novel “sad.” Tolstoy’s perceptions are too acute and all-encompassing to summarize so cleanly. It’s definetly not a dirge. Now maybe the ending is to certain readers….

Alex: Michelle and I have only made one post, and as far as I know it’s a one-shot. So I don’t think you have much to be afraid of. Even if we were regulars here, though, we’re very far from being BL bloggers (we write a collaborative post on the subject once a month, and that’s about the sum of it, give or take a random feature or review). Check out our blogs (or even just the features specifically mentioned in this post) and I think you’ll find that to be the case.

Hi, Alex! We haven’t been approached about future posts, so haven’t formed any lasting intentions about what our contributions at HU will entail, but we certainly are interested in many other genres besides BL.

The fact that our first column is BL happened by chance. Noah suggested we discuss a “mutually admired series,” and because I knew that Melinda loved this one and had long been planning to read it myself, I made the suggestion. Plus, it’s manhwa, which is a medium dear to her heart.

@Steven — I mean the Tolstoy novel. I’ve stayed far away from spoilers in general, but somewhere picked up the impression that it’s sad. But man, you are right about Tolstoy’s perceptions. He is a genius at creating a vivid character in, like, a paragraph.

Alex, part of our redesign is that we are going to become an all-BL blog.

Maybe we will occasionally have posts on Green Lantern.

Our name will be changed to BL and GL.

You heard it here first.

It’s pretty hard to make me LOL, but you, sir, have managed it!

Noah, can the GL posts also be BL? There’s gotta be some doujinshi out there…

GL, BL.

Say Noah, can Mr. Badman install a preview function???

Heh, I love that the fanfic you found, Noah, is not only GL, but GL/GA. BL GL GA… it’s like some kind of twist on shiritori.

I wanted to comment just to say how much I *enjoyed* this discussion. I loved the panels you used as examples, but mostly I just loved to see a much loved comic talked about in such a constructive way.

Thank you so much, Danielle! I’m very pleased you came over to read it.

Thank you!

Well, fine, M&M. Let me congratulate you on your generosity– this might be one of the longest posts on HU.

I look forward to your next articles!

Noah– I’ll take care of the GL half.

You mean a preview function for comments, Steven?

Yeah I hope so. It’s on the list….

“both of those guys are genuine tough guys, who have made it clear elsewhere in the story that they could seriously hurt their aggressors if they actually wanted to. I don’t want to say that this doesn’t happen in Japanese BL because as you point out, we’re getting filtered versions of this in English, but it is *really* welcome to me not to see a helpless little uke painfully struggling his way through forced sex.”

Perhaps I am less sensitive to this topic, but I really don’t see the “quailing victim uke” as a particularly common aspect of English-translated BL; offhand I can think of around 15-20 relationships along those lines, but there’s over 500 BL books/series in English at this point (and I’ve read most of them, be still my pocketbook…). On the other hand, I tend to avoid the “everybody’s butch” type of Japanese BL because it’s not my thing and leads into areas I don’t particularly like.

Of the types of Japanese uke that are underrepresented in licensed BL, the biggest omission is probably the hot-to-trot uke who jumps his seme and wants to get it on (and on, and on), which usually leads to a book that is too smutty for the bigger US imprints.

It’s a bit of a filter thing in the other direction; Korea has its share of helpless-victim fantasy in the doujin market, but as I said that material is less likely to be licensed.

I’m sure I’m especially sensitive to the “quailing victim uke” because I really hate it SO much. And much of my perspective is based on what I’m sent to review, since I’m not as much of a BL fan as some. But I feel like a significant percentage of what I’ve been sent includes that element.

Also, just to be clear, both the “tough guys” I mention (in U Don’t Know Me and Totally Captivated) are still wiry pretty boys. So I think they probably don’t fit into the “everybody’s butch” mold. Not like est em or something.

I will say that I haven’t seen it as much lately. I understand that there are fans of that kind of storyline, but many of the manga reviewers are not, and have been fairly vocal about it. It makes me wonder whether the publishers are listening.

I’d agree with Michelle, there’s been less of that lately. But the scars remain! :D

As always brilliant interaction, ladies ^^.

“Also, just to be clear, both the “tough guys” I mention (in U Don’t Know Me and Totally Captivated) are still wiry pretty boys. So I think they probably don’t fit into the “everybody’s butch” mold. Not like est em or something.”

Oh yes, I know; I very much like both of those. :) And est em too. The “everybody’s butch” BL I’m thinking of is the stuff that’s all about showing how macho and tough and aggressive and don’t-cross-me-I’m-badass the characters are. That gets old fast, for me. I like the cookie-baking softies. :)

JRB: Ah, I can certainly get on board with cookie-baking softies. :)

Estara: Thank you!

@danielle and estara – Thank you!

Pingback: Readers choice, favorite manga, and overlong series « MangaBlog

Pingback: Manhwa Monday: Dinosaur wars « Manhwa Bookshelf

Pingback: Manga Bookshelf | Fanservice Friday: Intimacy porn

I was pretty amused in reading the discussion. As a constant manga reader and also novel reader, this makes me more enthusiastic in reading the stories that would spark my interest.

Pingback: Manga Bookshelf | Off the Shelf: Fullmetal Alchemist

Pingback: Manga Bookshelf | Claiming our BL biases

Pingback: Manga Bookshelf | Off the Shelf: Moon Child

Pingback: Manga Bookshelf | Off the Shelf: Princess Knight

Pingback: Manga Bookshelf | Dabbling in Hate

Pingback: Manga Bookshelf | Off the Shelf: Chocolat

Pingback: Manga Bookshelf | BL Bookrack: The Heart of Thomas

Pingback: Manga Bookshelf | BL Bookrack: Totally Captivated, MMF Edition

Pingback: Manga Bookshelf | Off the Shelf: Basara, MMF Edition