I was of three minds,

Like a tree

In which there are three blackbirds.

—Wallace Stevens, Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird,

So what’s being compared here?

At first the answer seems fairly obvious; three minds are being compared to three blackbirds. When you think about it a little more, though, things get blurry. For one thing, the simile doesn’t quite map; the three minds are actually being compared to the tree, not to the blackbirds. So is there one overmind in which the three minds sit? Or is the tree the mind in which the blackbirds sit — or a number of minds, in which different explanations of the simile quietly caw? The poem doubles — or triples — back on itself; it seems to be describing or explaining its own processes. And if it’s talking about itself, the simile is there merely to multiply. The mind, the blackbird, and the poem are shadows that slide one into the other, each and each and each.

Or, to put it another way, the connection between the blackbird and the mind is arbitrary. That’s how metaphors work; they connect unlike things. Language is all metaphor; a string of arbitrary links, slipping signs that magically pull meaning out of non-meaning, like an infinite string of blackbirds rushing out of that tree, or mind, or poem. Wallace Stevens poems are built out of metaphors and think about metaphors, which is what I meant here when I said:

Wallace Stevens is very much about words. It’s words as imagery, but the point of most of his poems is the evanescence of those images; they’re arbitrary. They appear in language and disappear into language.

As a result, it’s not really possible — or at least very difficult — to create an illustration that works like a Wallace Stevens poem.

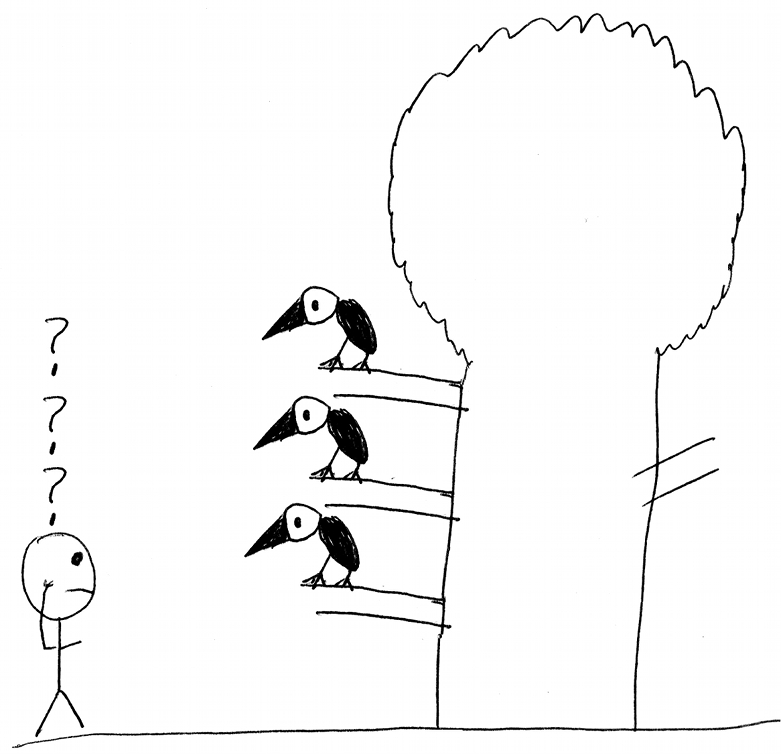

Though, of course, there isn’t anything to stop you from illustrating a Wallace Stevens poem. Nothing simpler. Here’s my own illustration of the above poem, taken from a zine I made way back in 2002.

This drawing neatly reverses the poem its illustrating. In Stevens, the mind comes first, and then the image of the blackbird follows. But in the illustration, the blackbirds are as solid as, and essentially precede, the split consciousness. Instead of three minds generating three blackbirds, the blackbirds generate three minds, represented by the chain of question marks. The poem spins an epistemological conundrum (what do I think?) into an ontological one (where are the blackbirds?) The illustration, on the other hand, takes an ontological question (what is the status of these multiple, poorly drawn critters?) and spins it into an epistemological one.

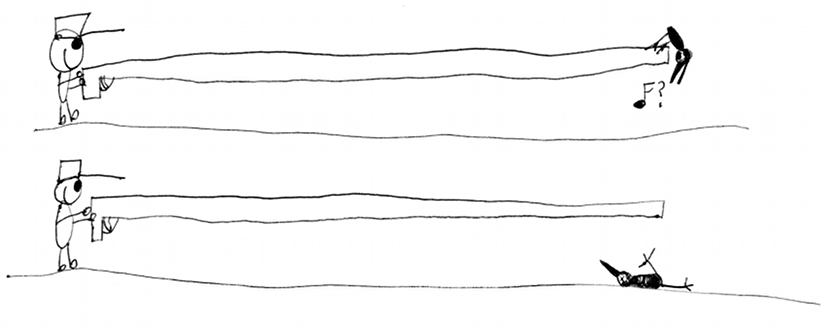

Here’s another example:

I do not know which to prefer,

The beauty of inflections

Or the beauty of innuendoes,

The blackbird whistling

Or just after.

Here, the illustration’s concreteness doesn’t so much mirror the poem as parody it. The poem treats the blackbird’s insubstantiality as sublime; the word is beautiful because it shimmers and passes; the singing depends on the silence and the silence on the singing. The illustration, by nailing down the ephermerality, reimagines it as (or teases out the implication of) violence. Language’s play is freedom — what separates us from the blackbird is that we can contemplate the blackbird. But that (loooooooooooooong separation) from the animal is also our knowledge of sin, which is the knowledge of death. The poem is about the joy of the world slipping into words. The illustration is, maybe, a reminder that, from the perspective of the blackbird, human mastery of the world may have a downside.

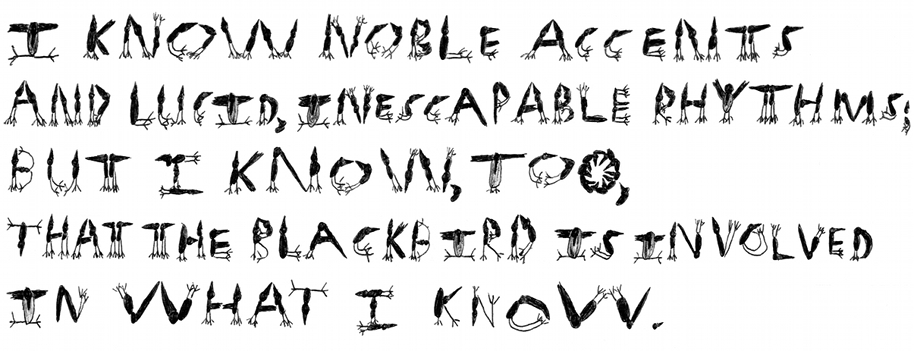

One last one…and here, I think, the illustration and the poem really do come close to meaning the same thing.

In “Thirteen Ways,” the blackbird stands in for both sign and signified. It’s the mark that points and the thing pointed to; the trace of a reality that can be indicated but not reached. The poem above can be read, perhaps, as an acknowledgement that words are not a self-contained system; the world is in there too, even if we can’t really tell exactly where. If words coat our images, then maybe images infest our words. We speak blackbirds — or at least something that looks a little bit like them.

“For one thing, the simile doesn’t quite map; the three minds are actually being compared to the tree, not to the blackbirds.”

Not to rain on your ontological, epistemological, and structuralist parade, but don’t you think you start out on a false premise? The simile does map. The three minds are the three blackbirds, and the tree is the narrator and Stevens himself. A metaphor transiting to a pantheistic conception of the universe…(well, this was half a joke to begin with).

Ha! That makes sense…though I think you could actually read it either way (that the “I” is the tree, or that the three minds are the tree.) It’s at least a little slippery…because it’s language!

It’s such a fabulous illustration of different ways of illustrating, and Noah has certainly done a fine job of arguing that images and words are at cross purposes. Words have referential freedom, images have incarnational presence. But words are put to a certain use by (the receptive context attributed to) Wallace Stevens, which is to deliberately make them serve no purpose except what words do– which, in Stevens’ case, often comes about through contemplating images. Modernism offers this possibility of liberated media– direct communication, like Rimbaud’s “alchemy of words,” Genesis P. Orridge’s concept of the musical “brown note” that makes everyone crap their pants involuntarily.

So it’s actually about liberating words not only from the crude instrumentalization of traditional forms or mundane commerce, but of actual referentiality, becoming something that (as Eddie Campbell was saying in that last thing) refers only to itself. This is the same mission images gave themselves, after the historical accidents of photography, typography, and general reproducibility completely changed the way people dealt with images. The idea is to create some new kind of community based on a myth of transcending history (which is completely legit), but it’s shared by visual imagery, sound, architecture, etc. etc.

So where do crude and clever cartoon illustrations fit in? Well, I may have to pick up that thread later, but the deinstrumentalization of instrumentalized images is something with a particular historic moment too.

This is why Imagism, though short-lived, is one of my favorite movements in poetry.

(But now I really do want illustrations for “Emperor of Ice Cream”.)

Hah!

I should post the whole zine, maybe; I have illustrations for every section. It’s a little bit of a pain putting it together, though, and I’m not sure how much interest there’d be….

You know Stevens isn’t imagism, though, right Joy? At least I don’t think he is…though he did know Pound I think…?

Illustrating Pound…ugh. I don’t want to do that….

I just lost a huge long comment. Damn. I was trying to say that Noah’s cartoons draw on highbrow (Dubuffet, Klee, Shrigley), middlebrow (New Yorker) and lowbrow (Chuck Jones) references in a way that deflates Stevens’ tone in a manner that’s more confusing than any alleged conflict between image and text. William Blake illustrated his poems too, in a far less literal approach, but in something of a similar spirit of making the purpose of the verses somehow more obscure than without the illustration.

Crap. Sign in damn it! The sign in’s at the bottom right.

For a moment I thought you were saying that Blake illustrated Stevens, but of course that’s not right. Pesky language.

That’s interesting though. So you think the deflation has to do with the style rather than with making the imagery concrete?

I just have trouble thinking how you could illustrate Stevens’ poems in a way that wouldn’t end up being really weird….

Maybe we should have a Stevens’ illustration roundtable? That would be pretty awesome.

Definitely not Imagist, though these particular poems by him remind me of the movement. That is, concrete images to express abstractions.

(And I wouldn’t want to illustrate Pound either. Illustrating many Imagist poems would be . . . well, pointless. Imagine illustrating William Carlos William’s The Red Wheelbarrow.)

I have no problem imagining an edition of Stevens with tasteful photographs (black and white perhaps) and/or gestural ukiyo-e-esque gesture drawings. Bleah.

Gestural gesture drawings. Yep.

Both of those would be pretty bizarre though, don’t you think? The Emperor of Ice Cream with a tasteful photograph of…what? An ice cream parlor?

Sign me up for the Stevens illustration round table. I also propose a time limit of 20 minutes per illustration, for the added fun of limitations, and to save us obsessives some grief…

Flowers in newspapers, a sickroom, a bare bulb, I don’t know. It would be sort of middlebrow, but it’s not that weird.

Sort of like “The Prophet” or something.

“As a result, it’s not really possible — or at least very difficult — to create an illustration that works like a Wallace Stevens poem.”

Actually, it’s not only possible. It has been done. Acquire David Hockney’s “The Blue Guitar: Etchings by David Hockney Who Was Inspired by Wallace Stevens Who Was Inspired by Pablo Picasso”

visible here:

http://www.amazon.com/Blue-Guitar-Etchings-Hockney-Inspired/dp/0902825038

one illustration is seen here:

http://www.ogallerie.com/auctions/2005-02/020180.jpg

I own the book and I assure you it is quite successful

Hmm. He’s obviously trying to get some of the abstraction/liquid nature of Stevens’ use of language there. And he’s picked up on the children’s nonsense-verse aspect, which is nice. Still, I think you end up with a gathering of objects rather than a real approximation of the way Stevens’ poetry works….

I’m not sure I’m that into that illustration, to tell you the truth. It kind of comes off as cutesy surrealism, without Stevens’ quickness of mind or elan…. Maybe I’d like it better in the context of the whole series, though….

Oh…and Sean, I don’t think we’d work with a time limit…though you could impose one on yourself of course!

I also want in on the Stevens illo-fest!

I was part of a group discussion thing last night on art and education, where I was arguing that both of those entities have a crisis of purpose, which led to cries of instrumentalization of the arts. To which I wish I would have responded- your content is your instrumentalization– not just your subject but your context of production. And in the case of fine art, it’s humanism. You can be more or less graceful about it, but the ideology of transparency, autonomy, and self-invention are inherent in anything that claims to stand for its own medium and objectal suchness.

I’m reading Chesterton on Thomas Aquinas…and he (Chesterton) feels that Aquinas’ contribution to philosophy is to insist on objectal suchness — which Chesterton does in fact link to an acceptance of images as opposed to Islamic icnonoclasm….

For what that’s worth.

Well, I’m at the disadvantage of not having read that bit of Chesterton, and you probably see this one coming, but… iconoclasm, to me, seems like the ultimate result of de-instrumentalization. Islamic art is deprived of purpose (illuminating the Divine), and so becomes “mere” decoration, or complete visual austerity.

I would cite for my Western example the end of the image qua image in modernist fine art, with minimalism and conceptualism. When art has a purpose, to depict Bible stories or tattoo a buttock, it is pretty obviously instrumentalized, and not being image qua image. Modernism is pretty straightforwardly Protestant. I am pretty sure Chesterton would rather look at a painting of the Virgin than a slab of steel lying on the floor in a white room.

I suspect that’s right about Chesterton’s preferences…though there’s a suchness to steel, too. Everything is something; he likes Aquinas because Aquinas takes the senses and the real world seriously — which would presumably include acknowledging the existence/value of a hunk of steel.

Right– and I love minimalism. But pretty much against its intentions– I find it absurd and funny, not transcendently iummanent. The whole point is the suchness of the steel, and I don’t much care for its Puritan pretension. I feel it’s detached from a master Signifier in a way that I find suspiciously fundamentalist. Which extends to my feelings on Wittgenstein and qualia, from the last conversation thread.

Although– there is a counter-strain in Minimalism that points past modernism, to installation art, earth, and phenomenology. Which is also problematic, but I applaud Minimalists for having two contradictory dimensions and being totally weird into the bargain.

And I have somewhat complex feelings about Aquinas– but I have complex feelings about most folks in between MLK and Kissinger (sorry I don’t know the appropriate medeival equivalents). He’s all about Aristotle and the natural order of things, and there’s always something a little menacing about the state of nature as a political axiom– whether it’s happy in Rousseau or not happy in Hobbes or sort of both in Nietzsche.

Beware of Chesterton. So seductive, so dangerous.

Oh pshaw. He’s not dangerous. He’s smart and insightful. I disagree with him a lot…but not more than I disagree with lots of other folks.

Chesterton pioneered a bizarre Catholic quasi-private socialism called “distributism.” Not appropos of this conversation, really, but it’s something I didn’t know until recently.

Yeah; he’s definitely anti-capitalism.

He was also a cartoonist.

Back when conservatives liked poor people and didn’t like wars. Good times, except for the epidemics and genocides.

Chesterton says that “suchness” comes from Aquinas? Weird. The notion was proposed by John Duns Scotus–as “haecceitas,” sometimes (unfortunately) translated as “haecceity.” See http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Duns_Scotus#Individuation . I don’t remember any mention of it in Aquinas. Maybe it’s there, but unless I totally spaced out when reading him, it’s not a major theme. Heidegger used to make a big deal of “haecceitas” in Duns Scotus, btw.

I’d love to participate in the Wallace Stevens illo roundtable, if I may. It could end up totally dorky–the first thing that came to mind was a groan-inducing, cliched “poetry-comic” version of “Anecdote of the Jar.” Come on, you can just see it! But I can also try to do it seriously…

No; neither Chesterton nor Aquinas use the term suchness. That’s me translating Chesterton’s take on Aquinas using my own terms, which are perhaps inadequate.

But Chesterton does see Aquinas’ central contribution as being more material than the materialists; taking the evidence of the senses seriously, which (Chesterton says) Aquinas is able to do because he sees the inadequacy of the senses as pointing to a greater reality rather than to unreality.

Very Chestertonian argument.

And you can absolutely participate in the illustration roundtable. It may take a little bit for me to organize it; other things on the table. But we’ll definitely do it, since there’s interest.

Well, in that case, you should check out Duns Scotus. And, based on how you describe it, also the notion of “suchness” in Buddhism, “tathata.” Which is close, though not exactly the same.

Also, John Hankiewicz is very influenced by Stevens; he did at least one one-pager explicitly about Stevens, but I think you can “hear” (or “see”) Stevens in much of the rest of his work–especially in his old “Tepid” minis.

Also, have you heard the Fibonaccis’ version of “The Ordinary Women”? That was how I first heard or read that poem, and while on page it may seem one of Stevens’ flimsier offerings, it’s beautiful when set to music.

Haven’t heard the Fibonaccis’ version. I love that poem though.

I’ll look out for Hankiewicz…. And maybe for Duns Scotus too, though I doubt I’ll be reading that anytime soon (Meister Eckhart first!)

Here:

http://www.fibonaccis.com/index.php/music/fibs/ordinary_women/

I don’t know how you’ll feel about it if you already love the poem… But I first heard this when I was twenty-one, and impressionable.

Whoops! I thought you meant they’d done Anecdote of the Jar! Sorry; reading too quickly… I don’t think I know Ordinary Women….

So how do you like it now?

Here’s some info on suchness in Zen/Buddhism. It’s all inadequate, ultimately, but that’s just the nature of the beast:

http://www.zenforuminternational.org/viewtopic.php?f=17&t=6047

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tath%C4%81t%C4%81/Dharmat%C4%81

And, of course, there’s always Dr. Johnson–notice that “thus”:

http://www.samueljohnson.com/refutati.html

I like the poem; iffy on the setting….

And of course I’ve seen that Johnson anecdote! Chesterton would approve, I’m sure….

Yo, Andrei! So you’re jammin’ the dunce caps on our heads? Truth mouth, Duns Scotus is da bomb, homes.

Sheesh…please tell me you’re not using ebonix to signify stupidity, Alex.

Next you’ll be sneering at Muhammad Ali like Gary Groth….

Nobody’s stupidity but mine own, Noah!

Quoting Roland Barthes, going back to the whole possibility of illustrating anything:

“Nor are linguists the only ones to be suspicious of the linguistic nature of the image; general opinion too has a vague conception of the image as an area of resistance to meaning- this in the name of a certain mythical idea of Life: the image is re-presentationwhich is to say ultimately resurrection, and, as we know, the intelligible is reputed antipathetic to lived experience… All images are polysemous; they imply, underlying their signifiers, a “floating chain” of signifieds, the reader able to choose some and ignore others.”

I will hold off for now on deploring the use of ebonics in earlier comments.

John Milbank hates Duns Scotus, and Deleuze loves hoim. He’s a voluntarist! If we’re going to get into Aquinas versus the Franciscans (versus Buddhism and Heidegger), this could be fun. I’ll have to read up.

I guess univocality is my form of modernist heresy– but it seems fine to let analogy exist only between tangible and intangible (natural and artificial, profane and divine).

That pretty much sums up poetry…

Pingback: Where Is The Stock Market Headed? Ask Me If I Care.... - Phil Pearlman