Preface.

So by way of a preface, you need to know that even though people talk a lot about all the comics references and history, in-jokes or savvy interpretation of the comic medium’s trajectory, Alec: How to Be an Artist works as a narrative even if you don’t really know what and who all those comics and comics people are.

Not that I think there’s anything wrong with the comics references and in-jokes. I just don’t get most of them more than cursorily. They don’t carry the weight of familiarity for me that I’m sure they do for most of you. I acknowledge that this surely means I’m missing something…

But I absolutely don’t feel that the book is some cliquish thing that nobody but a card-carrying life-long comics geek is allowed to read and appreciate. There’s a lot here for a reader like me – a reader whose aesthetic commitments have always been to prose fiction. Much of what’s here is close to the delights of prose narrative: evocative descriptions of environments and social interactions, ordinary familiar emotions, a strong sense of voice and narrator identity. Artistic enjoyment, and even ambition, aren’t only found in tightly managed formalist perfection. But that’s not to suggest, though, that there’s nothing of formal interest. There’s very sophisticated structure here. More on all that in a bit.

Not knowing those comics references particularly well just lets them fade a little into the background, even in this very comics-centric section, and makes all the other things that are happening more prominent. And those other things are very satisfying. And this post is about the other things.

A little more preface.

Well, ok, not all of the other things. There’s so much. There’s a lot of doubling, starting with the second person but perhaps most interestingly the use of quotation (mostly visual). There’s a lot about attachment and alienation. The identity of the artist is intentionally faceted and slippery (“You”, Alec, Campbell). I’ll come back to this, but this is one reason why I disagree with the notion that the narrative is solipsistic: the impracticality, even pointlessness, of solipsism is one of the book’s themes. Solipsism is alluring, but impossible. Art comes from other people, and other art, and from experiences in the world. That’s why peer groups – historical predecessors and colleagues — and the artistic culture and industry are so important to this narrative.

For me, the central theme of How to Be an Artist was this question of influence, the in-betweenness of autonomy and beholdenness: at the crossroads,

on the turnpike.

What do you buy when you sell your soul to the devil? You buy knowledge of the world. What is the price? The possibility of believing that nobody else matters.

What it means to be an artist is balancing on the knife edge of solipsism and selling out: perspective has to come from inside your head, but it must be meaningful to those outside. This book doesn’t ignore that — it’s about that. It may not be about how to be a successful artist, but it’s certainly about how to be a wise one. And it manages to be all those things, all the thematic sophistication and formal sophistication, while still being really atmospheric and descriptive and just plain pleasurable.

But I’m not going to talk about most of that though. Ok, a little bit about the pleasure. Maybe somebody will discuss the theme of influence. Maybe I’ll write another post.

But right now I’m going to talk about grammar, because with most comics there’s nothing to talk about. And Campbell’s prose is gorgeous.

Part 1.

Second person singular. Future perfect tense.

So he says, but he doesn’t actually stick with it throughout, despite the intro: it’s in plain old future most of the time. But the instincts are better than the rule: the shifts between future and present and the occasional actual past are vastly more effective than rigid future perfect would be. The use of the future perfect in the places he does use it, though, is sufficient to establish the bizarre temporality that that tense suggests, and that bizarre temporality saturates the rest of the section.

Lacan once noted that crazy people cannot think in the future perfect tense (the exact quote is that the emergence of identity is “a retroversion effect by which the subject becomes at each stage what he was before and announces himself — he will have been — only in the future perfect tense.”) Perhaps it’s due only to the power of suggestion, but I found the perspective of this book incredible sane.

The future perfect tense is powerful for its active assertion of inevitability and its blurring of passive and active. Technically, it suggests a point in the future prior to which a given action will have been completed: “I will have washed all my clothes by the time you get here.”

But in Campbell’s hands here, it refers to actions that have already been completed in the past, so the “present” tense of the grammar is the past tense for the reader. The result is a doubling of the vantage point and of the time of the narrative: the future perfect tense conveys the author’s narrative awareness of history while leaving intact the position of the character who has not yet experienced that history.

There is the time of the “you” – asserting and anticipating the future events. There is the time of the author, who knows what those events will be because he is already in the future that they point to. In other words, there is the time of the main character of the prose, and the time of the authorial voice.

But because this is comics, there is also the time of the pictures, which is (generally) the literary present. Not just because, often, the dialogue within a panel is in the present tense, but also because the time of an image, from the perspective of the image itself, is always the present, the moment present in the space that it represents.

This is a comic where both image and prose are fully active, fully explored. The full range of temporality from images, the full range of temporality from prose. That allows the time experienced by the narrative subject to be not just doubled but tripled: past, future, and present, all together, all represented simultaneously and equally.

Not only do I find this temporal pluralism quite satisfyingly nuanced – there’s something comfortingly unblinkered about such a temporal panopticon – as a formal structure it’s so much more ontologically fascinating and narratively flexible than the more mechanistic notion of sequential panels representing time as space. When prose is left behind, or replaced by “comics dialogue” that does not make full use of the toolkit of prose, images enforce a hegemony of the present. This causes a formal insistence on the presence of the panels that makes those kind of comics very insistently material and, I think, makes the immersive qualities of great literature harder to achieve. Comics are often Baroque, but they don’t have to be.

Much of the conceptual sophistication here comes from this recognition of how present to itself visual representation is. By choosing a verbal tense that essentially puts brackets around the present tense (the future perfect is both future and past), the time of the prose wraps the time of the images and breaks the hegemony of the visual present – you get all the immediacy of the visual present, but without its temporal solipsism. (Meaning “the time of the image is all that exists to the image,” not the psychological solipsism Vom and Noah mentioned.) The narrative vantage point is that of all possible times at the same time.

This is something comics can do that neither visual art nor prose can do alone. Because grammar is linear, it’s nearly impossible to get all possible times at the same time. You can grammatically nest the tenses, but you can’t get them all simultaneous, and if you’re not careful, tense shifts can become grammatical errors. But because images are always present to themselves, visual art always conveys a strong sense of the moment. In comics that emphasize sequentiality, you always have traces of what Heidegger called a “succession of nows.” When the prose and the images are more equal, each helps the other out of the ontological double bind, allowing for the native temporalities of both modes of representation to operate in concert.

(I rush to say, in the midst of all this grammar that’s about to become philosophy, that Campbell, unlike your present critic, gets all this ontological niftiness into his book effortlessly, leisurely, without sacrificing the liveliness and flow of the narrative or the believability of the characterization or the visual pleasure to the formal device. This is masterful. I’m sure I’ll get the criticism that none of what I’m talking about is the point of this book, and it doesn’t have to be. But the fact that it happens makes the book even more pleasurable for me.)

Heidegger in fact rejected the notion that time is an “uninterrupted succession of nows,” calling that notion “vulgar.” Instead he posited that the past, present, and future are unified, and that that unity is “ecstatic” – the ecstasy of the “potentiality of being.”

It makes sense that autobiography should be concerned with the ecstasy of the potentiality of being. There’s no question that the narrative arc of How to Be an Artist follows the typical frustrations that accompany putting artistic creativity in the service of earning a living: including the necessity of spending a lot of time in your own head, as other commenters here have noted. Being an artist is about being yourself too much and not enough. But I don’t think Campbell is unaware of this. I think it’s an intentional representation of those aspects of the creative life.

And perhaps that’s what comes across more when the comics references fade into the background. Campbell’s relationship to comics feels like my relationship to prose books. It’s affection, not fetish — but it’s also his job. He can’t exactly stop thinking about them. To be an artist you have to inhabit doubled worlds — the beloved world of books and the much less beloved world outside of books. Although someone who loves art but does not want to make it can escape into fictional worlds, and we can expect people who have no need for creativity to be utterly pragmatic and realist in their dealings with others, inhabiting both interior and exterior worlds is essential if you want to make art rather than consume it.

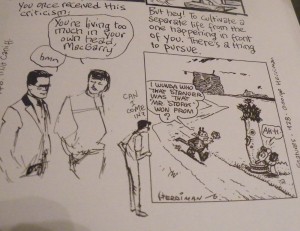

My favorite panel in How to Be an Artist gets at this directly.

Not sure I would have chosen to visit a place inhabited by a crazed brick-throwing rodent, but the image of “knocking on the door” of a fictional reality is utterly charming. There’s a difference between a self-aware introversion — one that has full access to the imagination — and solipsism, and for me at least, the formal structure and perspective of this work undercuts the notion that the introversion slips into solipsism. It’s hard to imagine a meaningful “life of the mind” that doesn’t happen inside the mind. After that panel is this extraordinary passage, which I’ll transcribe in prose to let how well-wrought it is come across more directly, although it’s more effective with the images (which among other things, change the rhythm):

But hey! to cultivate a separate life from the one happening in front of you. There’s a thing to pursue.

An inside life, where Fate talks to you, sometimes in the charming tones of a girl singer with old Jazz bands.

Othertimes in a naive wee voice in which all things are still possible.

Conceit is no criticism here in the realm of the spirit as it is in real time where your heroes are long gone.

On an airfield in China, Terry Lee is still kissing Jane Allen goodbye

In Gasoline Alley, Skeezix is having his midlife crisis

In a vast silent Arizona desert, a Coconino moon pours out molten silver…

It drips on Alec MacGarry, asleep at the turnpike

That’s Fate taking another voice, painting a new picture in your head

of the road you will follow when awake.

“Your heroes are long gone” — in the past.

“Still kissing Jane Allen goodbye” — in an eternal present.

“The road you will follow” — in the future.

This is the “potentiality of being” specific to the artistic mindset: “to cultivate a separate life from the one happening in front of you.” That describes an ecstasy of art, and part of the brilliance of this book is the recognition of how you find that ecstatic potential in the mundane life story. But the wisdom of that temporal panopticon is the point that being a successful artist requires saturating the life story with that ecstasy, so that the experience of the present is constantly imbued with the past and future, the “Picture in your head of the road you will follow when awake.” That ecstasy is something Campbell does extraordinarily well.

Part 2.

Art comics culture encourages a certain fetish of the image, especially the semiotically loaded image – or rather the related idea that pictures can take over the functions of narrative normally carried by words, that you can “read” images to construct narrative. Many of the most lauded art comics are works that pack the images with parsability – visual metaphor, visual narrative, symbolism. Inattentiveness to this often gets treated like a failure of literacy and images that aren’t packed to the semiotic breaking point become tainted as “mere illustration” (to quote from here).

But practically speaking, the result of this emphasis is a reduction of narrative to the barest bones of signification, because one of the things you lose when the images are as tightly meaningful as they generally are in the School of Heightened Visual Signification is the lushness of leisurely atmospheric description, which is a tremendously pleasurable part of fiction.

Witness this particularly visual segment from a book by a particularly visual prose writer, Don Delillo, (from Part 5 of Underworld), which I’m going to quote at its full lengthy length:

We were about thirty miles below the Canadian border in a rambling encampment that was mostly barracks and other frame structures, a harking back, maybe, to the missionary roots of the order — except the natives, in this case, were us. Poor city kids who showed promise; some frail-bodied types with photographic memories and a certain uncleanness about them; those who were bright but unstable; those who could not adjust; the ones whose adjustment was ordained by the state; a cluster of Latins from some Jesuit center in Venezuela, smart young men with a cosmopolitan style, freezing their weenies off; and a few farmboys from not so far away, shyer than borrowed suits.

“Sometimes I think the education we dispense is better suited to a fifty-year-old who feels he missed the point the first time around. Too many abstract ideas. Eternal verities left and right. You’d be better served looking at your shoe and naming the parts. You in particular, Shay, coming from the place you come from.”

This seemed to animate him. He leaned across the desk and gazed, is the word, at my wet boots.

“Those are ugly things, aren’t they?”

“Yes they are.”

“Name the parts. Go ahead. We’re not so chi chi here, we’re not so intellectually chic that we can’t test a student face-to-face.”

“Name the parts,” I said. “All right. Laces.”

“Laces. One to each shoe. Proceed.”

I lifted one foot and turned it awkwardly.

“Sole and heel.”

“Yes, go on.”

I set my foot back down and stared at the boot, which seemed about as blank as a closed brown box.

“Proceed, boy.”

“There’s not much to name, is there? A front and a top.”

“A front and a top. You make me want to weep.”

“The rounded part at the front.”

“You’re so eloquent I may have to pause to regain my composure. You’ve named the lace. What’s the flap under the lace?”

“The tongue.”

“Well?”

“I knew the name. I just didn’t see the thing.”

He made a show of draping himself across the desk, writhing slightly as if in the midst of some dire distress.

“You didn’t see the thing because you don’t know how to look. And you don’t know how to look because you don’t know the names.”

He tilted his chin in high rebuke, mostly theatrical, and withdrew his body from the surface of the desk, dropping his bottom into the swivel chair and looking at me again and then doing a decisive quarter turn and raising his right leg sufficiently so that the foot, the shoe, was posted upright at the edge of the desk.

A plain black everyday clerical shoe.

“Okay,” he said. “We know about the sole and heel.”

“Yes.”

“And we’ve identified the tongue and lace.”

“Yes,” I said.

With his finger he traced a strip of leather that went across the top edge of the shoe and dipped down under the lace.

“What is it?” I said.

“You tell me. What is it?”

“I don’t know.”

“It’s the cuff.”

“The cuff.”

“The cuff. And this stiff section over the heel. That’s the counter.”

“That’s the counter.”

“And this piece amidships between the cuff and the strip above the sole. That’s the quarter.”

“The quarter,” I said.

“And the strip above the sole. That’s the welt. Say it, boy.”

“The welt.”

“How everyday things lie hidden. Because we don’t know what they’re called. What’s the frontal area that covers the instep?”

“I don’t know.”

“You don’t know. It’s called the vamp.”

“The vamp.”

“Say it.”

“The vamp. The frontal area that covers the instep. I thought I wasn’t supposed to memorize.”

“Don’t memorize ideas. And don’t take us too seriously when we turn up our noses at rote learning. Rote helps build the man. You stick the lace through the what?”

“This I should know.”

“Of course you know. The perforations at either side of, and above, the tongue.”

“I can’t think of the word. Eyelet.”

“Maybe I’ll let you live after all.”

“The eyelets.”

“Yes. And the metal sheath at each end of the lace.”

He flicked the thing with his middle finger.

“This I don’t know in a million years.”

“The aglet.”

“Not in a million years.”

“The tag or aglet.”

“And the little metal ring that reinforces the rim of the eyelet through which the aglet passes. We’re doing the physics of language, Shay.”

“The little ring.”

“You see it?”

“Yes.”

“This is the grommet,” he said.

“Oh man.”

“The grommet. Learn it, know it and love it.”

“I’m going out of my mind.”

“This is the final arcane knowledge. And when I take my shoe to the shoemaker and he places it on a form to make repairs — a block shaped like a foot. This is called a what?”

“I don’t know.”

“A last.”

“My head is breaking apart.”

“Everyday things represent the most overlooked knowledge. These names are vital to your progress. Quotidian things. If they weren’t important, we wouldn’t use such a gorgeous Latinate word. Say it,” he said.

“Quotidian.”

“An extraordinary word that suggests the depth and reach of the commonplace.”

His white collar hung loose below his adam’s apple and the skin at his throat was going slack and ropy and it seemed to be catching him unprepared, old age, coming late but fast.

I put on my jacket.

“I meant to bring along a book for you,” he said.

Now, imagine a version of that passage in comics. First imagine it drawn by Chris Ware – and then imagine it drawn by Eddie Campbell. In my imagination, Ware’s version would undoubtedly involve a quite detailed technical diagram of a shoe, as arcane knowledge is a bit of his bailiwick, and he would surely be able to capture the intensity of the thematic point, the buildup to the “gorgeous Latinate word.” It would probably, in fact, be an even more pointed buildup.

But much of the realism and atmosphere of that scene come from the rhythm of the speech and the texture and atmosphere of the descriptions. And that’s separate from the metaphors. Even though visuals are suggested, the visuals aren’t the point. The narrative trajectory is only part of the passage’s impact: that’s its significance, not its effect. Campbell’s grasp of and appreciation for prose makes me believe he could capture the visceral tactility — the awareness of how things feel and look, as well as the description of how they feel and look — and the dialogic humor of the passage as well. Prose literary narrative doesn’t just convey emotion and story; it also suggests imagery and demarcates space and evokes setting and represents the mental experience of having experiences — and it accomplishes those things in ways that are quite different from the ways they’re accomplished in primarily visual narrative. Since comics in fact has a quite native place for prose writing to occur, letting cartoonists off the hook for doing it well it is significant critical failure in my book. Campbell does write prose extraordinarily well, and it makes all the difference.

By not rejecting real honest-to-God prose (as opposed to “comics dialogue”), by letting his pictures sometimes just be about gesture or mood or setting and the parts of literary meaning that traffic in images and visuals, Campbell gets to something that feels so much more like visual literature than many other cartoonists, who are doing something closer to “literary art.” His drawings are atmospheric, suggestive, not illustration but illustrative. And great literature is all of those things.

That’s why “mere illustration” is so terribly wrong, and why the hegemony of symbolic and metaphorical and even narrative images as a substitute for really outstanding prose writing does so much violence to the potential of the form.

It seems like atmosphere and illustration are broadly associated with the pulpier genres of comics, with genre comics rather than art comics. But there are literary ways to handle atmosphere and description too, and it matters that comics can do this, can be literary in this particular way. It’s an achievement, and it doesn’t matter that it’s not pushing the envelope of visual semiotics. It’s literature. It’s doing interesting literary things. It’s allowing visual imagery and literary imagery to overlap and converse.

I hesitated before writing this, because after a year of writing here I feel like a lot of people will take this as my selling Campbell short, not paying attention to the art or the potential of art or giving the art enough autonomy. I’ve been chastised so often for wanting comics to be ambitious in ways that are familiar and beloved to me from prose literature, an ambition that does not require a baroque disjointed reading but allows immersion, sophisticated and subtle and smart without getting tangled up in so many formalist visual tricks that they feel stiff and micromanaged. The more packed with significance a picture is, the less those things can come to the fore. This argument is often made by saying that comics should do something unique, that they don’t need to be like literature because they can be their own unique thing. But for me, the experience of reading Campbell’s writing — and I strongly prefer the ones where he’s the writer although I like his art when he’s not — is unique: it’s just a unique form of literature, rather than a unique form of something else that really isn’t literature at all.

Comics at their best are a tightened and compacted form: the classic example is always Peanuts, with its ability to cull away all the chaff and leave only the essential bits. Many comics where images carry the narrative tighten by reduction, because you just can’t pack as much into an image as you can into an extended prose passage, and you can only repeat the image so often for subtle effect before you’ve got a flip book instead of a comic. Comics that use that strategy reduce the narrative to the most essential elements, and then convey those elements through the images. There can be extraordinary power in that approach.

But Campbell’s stories, because he doesn’t cast aside prose, can condense without reducing. The description and atmosphere and even rhythm that takes so much room to establish in prose can easily be encapsulated into a single evocative frame. I don’t mean that this is all Campbell’s panels do; sometimes they are packed with signification, but sometimes they aren’t, and because they’re working with prose rather than instead of prose, it becomes an artistic choice rather than a requirement for the narrative flow. The shape of the narrative is changed from prose to comics: the form is compacted, but the narrative itself is as big and rich and full as a full-fledged novel. Campbell’s books are bigger on the inside than the outside. And I think that’s what art is all about.

Finale.

By way of a postscript, my friend Chris, whom regular readers may remember as my interlocutor in the Swamp Thing Roundtable, once got a letter published in The Comics Journal back in April of 1997. I’ve reprinted it below.

“I was extremely saddened to learn of Stan Drake’s passing. He was truly one of comics’ finest craftsmen, as clearly shown by the panel you folks ran with his obit. Who could forget The Heart of Juliet Jones, that great schizophrenic-vigilante strip he collaborated on with scripter Doug Moench and inker Klaus Janson during the early ’80s?

“I only regret that you couldn’t find the space to run a panel or two of his later, more mature work on titles such as Elektra: Assassin and Stray Toasters. Ah, well…”

The Comics Journal titled it “Ouch.”

________

Update by Noah: The entire Campbell roundtable is here.

Caroline-

This has given me a lot to chew on. You’ve centered in on something that’s given me trouble with Campbell’s autobio work- I love his prose, I love his illustrations, and yet his work writing for himself hasn’t always worked for me as comics. I think it’s just a fundamental disagreement I have with his selected word/image balance. Maybe it’s time I retire this as an aesthetic criteria and begin to regard it as personal preference. (although I still think it’s interesting that works that have been popular with non-comic readers tend to be balanced more heavily towards the word and narration, and contain less moment-to-moment visual narrative).

Lastly, I enjoy the future perfect tense of Artist to a point, but it also serves to make his judgments of his fellow creators extremely harsh. Maybe that’s less of an issue for others than myself, but although I enjoyed Artist immensely, I was really put off by some of his judgments, and the tense reinforces the idea of a kind of permanence or authority to those judgments. And so in some ways those condemnations of books I happen to enjoy become one of the major things I can recall about the book.

“word/image balance”

You think there’s too much word in Campbell’s work? It’s seems on the light side compared to some others, like many parts of Cerebus, or Posy Simmonds, or even Carol Tyler.

Excellent essay, Caro! There are things I would quibble with, and I can’t stand Delillo (to be fair, I think I put down Underworld before I got to that nice passage…) — but this is probably the best thing I’ve read on Campbell, plus it’s great on an underappreciated, constituent element of comics.

Somebody else will hopefully talk more about about the graphics — I think you perhaps drop the ball a little on that in your hypothetical comparison with Ware.

Derik-

>>You think there’s too much word in Campbell’s work? It’s seems on the light side compared to some others, like many parts of Cerebus, or Posy Simmonds, or even Carol Tyler.>>

Well, there are extremely wordy portions of Cerebus- portions of almost complete text, in fact. These are countered by portions where the image carries the scene- scenes in which there are virtually no text at all. I don’t find the same thing to be true with the 300-odd pages of Campbell semi-autobiographical comics I’ve read, but “silent” i.e. wordless sequences are used quite effectively in “From Hell,” which he drew but didn’t write. Campbell has an advantage over a lot of other “wordy” cartoonists in that his images often work agains/change the meaning of his prose, but I do think it’s unfortunate that they’re never allowed to take over. Guy Delisle is a cartoonist that comes to mind that has a similar dense approach to Campbell but also allows room for silences and unpacked scenes as well.

Still digesting this essay, but just a quick comment regarding Campbell’s panels working with prose rather than instead of prose — I seem to recall Campbell at one point in his one of his various statements or arguments over the definition of “graphic novel” and the classification of comics that he’d come to imagine his work (and possibly comics as a whole) as an extension of the illustrated novel, with the illustrations doing various amounts of narrative lifting depending on the artist. I may be misremembering that, though…I’ll have to try and find the citation…

Jason- Interesting. That’s That’s exactly what I was getting at, explained much more clearly. I think, besides an ingrained aesthetic preference towards the reverse, I also have some reluctance to embrace this approach because it seems to slough off some of what is unique to what comics can do. I guess if we had to make a category for the kind of balance I personally favor, we could call it “cinematic”?

Caro: “the time of an image, from the perspective of the image itself, is always the present, the moment present in the space that it represents.”

I’m not so sure. Gilles Deleuze talks about the crystal-image. For instance: http://tinyurl.com/6awmfup

Sean, have you read Simmonds? I think she provides a nice mix of the “cinematic” (uggh) and prose. Using each to their strengths, imo.

Domingos, that painting is fabulous.

Sean,

“Cinematic” qualities have certainly made their way into comics over the years, from Will Eisner translating effects from Orson Welles into early Spirit comics, to Moore drawing on Roeg and Lynch for pacing strategies, to Ellis and Hitch appropriating the “widescreen” aesthetic for action scenes in The Authority. I think there’s a problem inherent in fetishizing the “cinematic” in comics, though, which is a subordination of comics to “movies on paper”. Brian Michael Bendis comics suffer from this often — imitating the semi-static cinematic progression strategies from Watchmen but without utilizing the “deep focus” aspects of comics (that as an illustration, all portions of a single drawing can be occurring “at once” without the need to isolate certain dialogue in a sound track or be mindful of how long a given image is on a screen).

Additionally, I think that there are a lot of qualities unique to the combination of image and text, but that comics are only one form of image + text combination. My primary example would be the use of “doodles” in Kurt Vonnegut’s BREAKFAST OF CHAMPIONS. Vonnegut’s novel is without question a novel, rather than a comic, but the images he includes are crucial to his aesthetic achievements in the work. I think that the proper spectrum of work to consider when discussing comics would include work like Breakfast.

Derik-

I haven’t read any of Simmons’ work yet- I’ll have to pick some up. I haven’t even flipped through Tamara Drewe- I was a little bit put off by the cover image- but it sounds like I need to do so.

As to “cinematic”- I know, I know- I just don’t know how else to name the particular approach. Of course, huge swaths of Japanese comics favor the approach, and the economic conditions involved are more favorable to such a thing. In fact, I wouldn’t be surprised if the denseness of some of the Alec material doesn’t have a similar (reverse) economic basis. I just re-read the 1986 Baccus/Deadface stories and they have several moments of silence, and not all of them action oriented- people pouring wine, serving food etc. Of course, they also have tremendously compressed narrative elements that tilt things a little farther in the other direction. Not to bring too many film comparisons to bear, but- if you can afford the slow crane shot that shows us the locations at which the action will unfold in a story, why not show us rather than a narrator describing them? If a cartoonist has an entire arsenal of visual solutions to a primarily visual problem, why not use them to bear on the situation?

Jason, I’d be very interested to hear you expand on your “extended comics” thoughts. Would you also consider strong writer/illustrator combinations (for instance, Dahl/Blake)? The other example that immediately sprang to mind was “Tristam Shandy”- although not for any illustrations, but the actual visual formatting of the text altering meaning of said text.

Thanks everybody! It will probably take me awhile to process the comments but a couple of quick points:

Domingos, I think that particular painting is an example of the same phenomenon you get when you nest tenses in grammar: it’s a device like a tense shift more than an actual past-tense image. That’s more a cluster of images making up an image: each discrete image is present to itself. It’s like having a sentence in the present tense with a clause in the past tense inside it.

I think that’s different from what happens in this comic: that’s a more conventionally “grammatical” tense than the net effect of the prose and picture together.

I can see applying crystal-image to that, they’re both essentially “present-perfect”, but crystal-image involves the perspective of viewing the image, which is what I was excluding when I said “from the perspective of the image.” Deleuze’s concept is epistemological, whereas my point is merely grammatical. But it’s something I can make clearer.

Speaking of things I can make clearer, thank you Matthias. :) I almost didn’t post Part 2 of this because I agree that it’s thin on the graphics, much more a suggestion than a fully fleshed out argument. Perhaps I’ll put a followup into the queue.

What in the world could you possibly not like about Delillo! ;)

Jason and Sean: I need to wrestle with your comments a bit. I have a tendency to want to blow out “comics” to include as many possibilities of image + text as possible, to encourage interplay among them and commonality rather than distinctions. It seems like comics are a rich enough medium that there should be a plurality of comics genres based on form and that the varied balance of word and image could be part of that (rather than just the rather undescriptive sub-subculture categories that pass for genre categories at the moment: “art” and “mainstream” and “underground” and so forth).

I knew Matthias would turn up in comments when I was halfway through this, and I agree with him as to the quality of this article. I have sometimes wondered who are/were the best prose stylists in comics. I don’t know if it’s Campbell but he’s better than many of his contemporaries. His choice of the Herriman is certainly not accidental in that respect (the language in particular, Krazy’s delusion, the head beaning etc.).

I have a few of the same reservations as Matthias. For example, this: “…as a formal structure it’s so much more ontologically fascinating and narratively flexible than the more mechanistic notion of sequential panels representing time as space,” which I would object to; the “fascination” derived being dependent on the skill of the artist not the form. Images, I feel, can be deployed like words and give us some of the rhythms of the Delillo passage you cite.

And I agree that comics should be blown out to include as many possibilities as possible. It’s just that the prose aspects have been least explored in the American alternatives/art comics scene.

Jason: “I seem to recall Campbell at one point in his one of his various statements or arguments over the definition of “graphic novel” and the classification of comics that he’d come to imagine his work (and possibly comics as a whole) as an extension of the illustrated novel…”

I think he’s said this a few times, but I believe the first time I read it was on the TCJ message board.

Thank you, Suat. I admit that’s an evaluative claim and you’re right that fascination is objective. I tend to buy Heidegger’s critique of moment-to-moment sequential temporality, though, so it would take a very skilled artist indeed to make me fascinated by any structure drawing on that sequentiality!

Did you read Charles’ post over at The Panelists about how the comics he thinks are the best have a disruptive quality (which I refer to here as Baroque, quoting Lethem) that calls attention to their meaning-making? That’s very much my experience of the way semiotically saturated images behave. I think that disruption makes it hard to get the immersion of the Delillo. Prose isn’t really sequential — it’s more continuous, and it’s hard for a sequence of still images to replicate that.

But perhaps not impossible, eh?

I just want to add on in response to this “It’s just that the prose aspects have been least explored in the American alternatives/art comics scene.”

At the risk of sounding whiny, sometimes it really does feel like there’s a widespread anti-prose conspiracy in alternative comics. I don’t think there really is; I think it’s that everybody thinks the non-prose stuff needs building up and defending, and I think there are a lot of people who genuinely just like it better. And I also think that there’s pressure in art comics for the creator to be a auteur, collaboration has a mainstream comics taint, and it’s more rare for a person to be really incredibly talented at both prose and drawing than it is for a person to be talented at one or the other, and it easier for an artist to write something than it is for an writer to draw something, because basic art literacy (art-acy?) is so poor in the US.

There are comics that I really love where the images carry the narrative, and comics I adore where the images carry the semiotic work but are non-narrative. But I wish prose were more beloved and embraced too. It seems like such a missed opportunity.

Well, there’s an awful lot of territory to be claimed out there, Caroline. Scott McCloud stuck the Comics flag on hieroglyphics and various narrative relief sculpture traditions- why not plant yours on concrete poetry?

Not sarcastic, by the way- it’s intriguing.

Last little comment before I go- have any of you ever read David Lasky’s “pictureless” comics adaptation of the Raven? It’s pretty remarkable.

And it can be found at the bottom of this Flickr page. I like his Pear comics better, and his “adaptation” of Joyce. I think Barron Storey is an interesting example of a comics artist (of sorts) who mixes prose with images.

Caro: I didn’t really get that it was the immersion you were after. I thought ellipsis and space for the reader to “insert” himself, but maybe that results in the same thing. That is pretty subjective since a lot of the commenters above might feel a more kindred spirit with images than text even if images are more concrete. I can see why you’re attracted to some of the comics of Jason Overby based on what you write in the first 2 paragraphs of Part 2.

Ack! I’m reading along and grooving on Caro tossing around comics and space and time and then I get this as an example of stellar prose:

“But hey! to cultivate a separate life from the one happening in front of you. There’s a thing to pursue.

An inside life, where Fate talks to you, sometimes in the charming tones of a girl singer with old Jazz bands.

Othertimes in a naive wee voice in which all things are still possible.”

And I just want to bang my head against the wall.

I just…to me that’s such romanticized, sub-Beat, stentorian self-dramatizing bosh. If I never, ever, hear anyone reference girl singers in Jazz bands as some sort of ne plus ultra of authentic wonderfulness again, then I will have died only hearing it about fifty billion times too many. And “a naive wee voice in which all things are still possible.” Fucking gag me.

Really, I have a visceral loathing of that passage. It’s slam poetry crap.

And part of what I hate about it is exactly the time slips that Caro describes. Maybe I suffered too much damage from my youthful immersion in contemporary poetry, I dunno…but so many, many ungodly contemporary poems (and maybe not just contemporary, but…) end in this lyrical future tense. And it’s supposed to do exactly what Caro says here:

“This is the “potentiality of being” specific to the artistic mindset: “to cultivate a separate life from the one happening in front of you.” That describes an ecstasy of art, and part of the brilliance of this book is the recognition of that ecstatic potential in the mundane life story.”

The world is cut off from the world and made poetic; the mundane is made lyrical. Or, alternately, you could say that the world is picked up and dumped in the poetry machine and then you turn the crank. And out comes ecstasy, hoorah.

I don’t think there is an artistic mindset. I don’t think there should be. I don’t think artists are priests, who make the world ecstatic through their transcendent quiet inwardness; who cast a glamour on the earth through their numbing recitation of important aesthetic touchstones (girl singers! Krazy Kat!)

I think this quote points to what made this book so unpleasurable for me:

“Solipsism is alluring, but impossible. Art comes from other people, and other art, and from experiences in the world. ”

The thing that interferes with solipsism is that it doesn’t fit with art. You start with the need for art, and that leads you to realize that the world has to be there too. But the problem is…for me, in this book, the world is *always* there for the art. The experiences are all there to be chucked into the poetry machine. That’s what happens to his wife and his baby; new fatherhood gets transmuted into standard-issue poetry tropes. That’s what it’s there for. Which I find both, yes, solipsistic, and also really depressing.

Obviously that’s not what others are getting from this, and

I appreciate that, and I think this essay is lovely, but…man, it makes me like the book even less, not more.

___________

And just because this comment isn’t long enough…and I want to say something positive….I think the discussion of prose is really interesting…but I think that you’re kind of missing out on what Charles Schulz is doing if you’re arguing that he’s using condensed meaning in images as a substitute for prose. I think Peanuts is probably as prose the best-written comic, period — certainly better written than Alec, to my mind, though not as wordy obviously. Better written than Delillo too, by a long shot. Schulz had a really idiosyncratic ear for language and a love for words. Some of his strips are sight gags, but a lot of them would pretty much work without the pictures; they’re about puns and verbal dead ends and misunderstandings and different registers of language. He’s usually thought of as a minimalist because of the drawings obviously; but thinking about your essay, you could also see the sparseness of the drawings as a way to give room for the language; as you say, the drawings become a kind of rhythmic device rather than a meaning making one.

I mostly agree with that reading of Schulz, Noah, except for the part about him being a better writer than Delillo because HONESTLY. Pfft.

Rereading I should definitely make the Peanuts reference clearer. (I think that falls into the same category as the reference to Ware.) I wasn’t thinking so much of Peanuts condensing as a substitute for prose as just an example of the way comics use distillation to great effect. But I do think there’s less stuff, less formal or structural stuff, that is, going on in some equivalently sized chunk of Peanuts than in here. What Peanuts does it does flawlessly, and thematically it’s very rich, but it’s a comparatively simple set of formal and literary devices, brilliantly flexible and put to tremendous effect. The formal and literary devices in this one aren’t really all that simple. So I think Peanuts is “reduced,” although “distilled” is probably a more apt word, whereas this is “condensed.”

I can be talked out of the vocabulary there, though. I don’t want to imply evaluation between them, just to notice the differences. I don’t think Peanuts is doing the same kind of thing as Delillo and I don’t think saying that is an insult to either one.

I think there is a little bit of suspicion, or at least ambivalence, about the Romantic Artist tropes in the book, that I didn’t get into this review at all. If I’d managed to find the time to really dig into some close reading, that’s one of the things I’d have liked to work out and point to more diligently. I think it comes across in some of the self-deprecation and in some of the anxiety. I think the representations of Alec in the chapter are far more pragmatic than the words: there’s a lot of craft that sneaks in that I didn’t touch on at all, and it mitigates some of this romantic streak.

But I don’t think it’s ultimately a killing ambivalence — I think a certain Romantic Introversion is still part of what it means to be this kind of “serious artist.” Loving art, escaping into art, building an interior life that feeds art — those are good things too. It’s not all just craft: you do have to care. And I don’t have an objection to lyricism. Too much clamour makes my head hurt.

And for the record, culling the language out of the comic into prose makes it less effective than it is with the pictures — but it’s so much MORE effective than almost ANYBODY else’s language would be under the same treatment that I still think it was worth triggering your Beat-nix reflex.

Suat, there was a time when I would have not said I was after immersion, as it’s not something I think of as characteristic of the postmodern prose I tend to like the best. But compared to really Baroque comics, even the most experimental fiction is immersive — because of that continuousness of prose, I think. Honestly, and this is going to make me sound like an absolutely insane person, I do realize this — I experienced William Burroughs’ Soft Machine as more immersive than Human Diastrophism.

Hmmm, concrete poetry. I’m going to think hard about that.

I will take your “pfft” and raise you a “nyah!” Further, I will take, “Why aren’t you two ponies?” over the entire collected works of Dom Delilo. Throw in all of Cormac McCarthy too.

Schulz isn’t about complicated, there’s no doubt about that. Unless you think koans are complicated. Which they kind of are.

I don’t like that passage any more with the images, I’m afraid.

I think that the book romanticizes the craft as well. That’s the wine-tasting meme, and the connoisseurship. And actually the sequence Suat emphasizes about figuring out the dots.

I don’t dislike lyricism…but if I follow that thought up I’m really going to start ragging on the book again, and I think I’ve probably done enough of that for everyone.

I’m reading Hume at the moment, and I find that much more immersive than Alec.

Oh, you can have the Cormac McCarthy. I can’t get past the brutality with him. I had this idea that I was going to build up to it by reading other less-violent violent books and I just got really depressed. But if anybody’s interested in that sort of thing, I thought Doctorow’s Hard Times was pretty good.

Delillo rocks, though. That scene in the grocery store in White Noise with the Elvis Studies and the generic bacon, and the Lenny Bruce monologues for the Missile Crisis. R.O.T.F.L.

I feel like I’ve ended up overstating the romanticism, maybe, because I like it. I’ll have to think about that as I revise.

(Of course, you probably don’t think I’ve overstated it LOL. But I think I probably have.)

Well, you’ve semi-convinced me to try Delilo again. I’ve had no success before, but you never know….

The Lenny Bruce stuff is in Underworld. That’s not clear from what I said. What did you read before? White Noise is definitely the place to start, or maybe End Zone, although I’m especially fond of Americana.

I think I tried White Noise. Didn’t get past a page or two. But try try again….

Maybe try End Zone. It’s about race and nuclear war and football. White Noise has enough academic satire that’ll probably put you off.

You couldn’t get past the first few pages of White Noise (and the quotations in that review of Falling Man in the NYRoB) and you want to try Underworld and the rest? Masochism of a very high order indeed.

No love for Blood Meridian? That book is better than all of Doctorow methinks (well, whatever I’ve read anyway). I feel a Bill the Cat epithet coming on…

Blood Meridian: I can’t read it! I’m terrified! All that blood…

So I have no idea whether it’s better than Doctorow LOL. I just know it scares me.

fwiw, that link to the Lasky “Raven” adaptation is only part of the story. It goes on longer (and more interestingly, in its use of black shadow/silhouettes in the panels).

In re prose in comics, I think too many comics reader start to draw some hard lines when comics move across the spectrum towards illustrated novel, which is kind of funny if you think about all the early outrage about comics causing kids to not read actual books (ie prose).

Coincidentally, I just got in the mail a copy of Martin Vaughn-James L’Enquêteur, which is described as a “roman visuel” (visual novel). It’s a combo of half image/half prose pages, all prose pages, all image pages. More than a novel with illustrations, more than a comic with lots of prose. Haven’t read it yet, so I don’t know how successful it is, but just the form of it is pretty interesting. A further step on that spectrum.

Harry Morgan writes about such issues in his Principes des litterature dessinee. He uses the term “drawn literature” as an overarching term that includes both comics and illustrated novels.

Personally, I’d love to see more prose in comics.

The Lasky “Raven” appears to be a little tricky to locate. Is it going to be readily available if I just work a little harder?

That Martin Vaughn-James novel sounds quite lovely; I’m remembering a conversation where Andrei recommended him but had some opinions about works of varying quality. If Andrei’s on perhaps he can comment about how successful it is?

I AGREE about the funny re comics causing kids not to read actual books. And, for me at least, what’s so sad about it is that there really aren’t a lot of illustrated novels: it’s a much more underexplored genre than what we think of as “art comics”.

I think, in the US at least, some of it really does come back to art education: everybody basically learns to read, or learns to read basically. Not everybody learns to draw basically. That skews comics toward the visual art world, because people who make the effort to learn visual art are the only people who can really fully participate. But I think that is just a material effect of the “conditions of production” that could be changed.

Perhaps Alex if he is lurking around can tell us about basic art education in France and whether the better health of BD is in any way supported by it.

P.S.: I suddenly have this comical image of Colonel Sherman Potter writing books about French comics.

I’ll bug David about putting the rest of the story up when I talk to him this weekend.

I think one of the problems you get into with very dense prose passages is when they’re worked into/interwoven into a more visually dense narrative, ala “Jaka’s Story” or “Thieves and Kings”- the immediacy of the visuals can make the prose initially a chore. Not so (I’d imagine) with work that skews that way from the outset. And I think you’re totally on target with the art education observation, but it probably also has to do with the historical antecedents of comics in North America, i.e. garish visual entertainment.

Alas, I’m too far away from my days in the classroom, either as a pupil or as a trainee art teacher. But it is disquieting; when I was a little boy,we were really taught how to draw.

But when I studied at Arts Plastiques Paris 1 (which trains art teachers) we didn’t even have drawing classes.

My take on the success of BD and pictures in general: it’s due to France (and Spain, and Italy) being Catholic countries. The Roman Catholic Church has never been iconoclastic. RC countries thrive on images!

Sean: Some of that could be the prose itself. I don’t recall “Thieves and Kings” being particularly… well written. Jaka’s Story is I think more successful in that respect.

There’s probably something to the educational argument, though surely it’s self-supporting to to some degree now. That is, standards are higher for drawing than for writing, at least among comics with some pretense to aesthetic quality. (Mainstream drawing can be as horrible as mainstream writing, and no one seems to much care, so I guess there’s a kind of equivalency in that realm….)

I am in agreement as to the… varying qualities.. of the two examples. When reading Jaka’s Story, though, I’ve found a kind of reluctance in my reader self when switching gears/switching into the other reading mode, and I can’t help but think it’s a matter of pacing, immersion, and speed of gratification. It’s possible that, with more training, i.e. being exposed to more works that navigate that threshhold, I would lose this reluctance. Just to be clear, I read plenty of prose and prose novels, it’s the transition between the reading modes that can be bumpy for me, at least currently.

Self-supporting, yes, probably. Anybody know anything about the writing curriculum at Center for Cartoon Studies? Sturm’s a bright and literate guy as far as I can tell. Those graduates seem very much artists rather than writers, though (from limited experience). Maybe some of the other artists can tell us what they were taught about writing.

Of course, not that writing education in writing programs is all that, either, now that we’re mentioning it. But it’s nonetheless an actual writing curriculum.

I guess my point, Noah, was more that there are fewer people who have real talent in writing and have spent a lot of time practicing writing who are even vaguely passable artists than the other way ’round.

As you say, the standards for drawing are just higher. Imagine the response to a brilliantly written comic that had drawing comparable in quality to the prose that we’re stuck with in most art comics.

I pick things up sometimes and I alternate between wanting to cry and getting REALLY FUCKING FURIOUSLY ANGRY at the poor quality of the prose part, and how people apparently think that writing is this intuitive something that anybody can do with just the exposure given to them by their high-school.

But comics is hardly alone in devaluing writing as a skill that takes work and practice…

I actually agree fairly wholeheartedly — there’s a lot of inept prose in comics. It’s a medium that attracts more visual artists than it does writers, at least in art comics. Mainstream comics is somewhat different and for all their formulae, the writing is often better crafted than what you see in art comics, I think.

Campbell being lyrical doesn’t happen all that often, which is in part why I find the sequence quoted to pack such a punch. I actually prefer some of the stuff that follows, but it does have to be read along with the images. His real accomplishment as a prose writer, however, is the way he achieves a kind of neutral-seeming tone in his narration of the quotidian; the warmth and keenness he brings to it without it becoming obvious. He’s a writer I tend to enjoy returning to, like an old friend. I feel like I’m in good hands.

Anyway, that’s all very subjective; given more time, I might come up with a more compelling analysis of his prose, but while we’re at the subjective, I guess I just want to add a little to my stated disdain for Delillo. He is one of the most pompous, self-impressed writers I’ve had the misfortune to encounter in recent years. I should note that the only thing I’ve read is about 2/3 of Underworld, after which I disposed of it for good.

He seems to want to pack every single passage of his with precious meaning, and – often – momentous significance. There’s never anything ordinary about what goes on in that book. Plus everything is sooo smart. After a while of feeling obliged to take him seriously, I just randomly started to read sentences aloud, which made it much, much more entertaining.

Even that acclaimed set piece in Yankee Stadium that opens the book. Yeah, I can see that it is virtuoso piece of prose, but jeez, it’s so self-important. And the clincher, with J. Edgar Hoover pocketing the LIFE Magazine page showing Bruegel’s “Triumph of Death” that just *happens* to drift into his hand… could it be more showy and pompous? (and no, it doesn’t help that Delillo has done his research and confirmed that LIFE actually printed that image around that time).

Sorry for ranting.

“Anybody know anything about the writing curriculum at Center for Cartoon Studies?”

Judging from what I’ve seen coming out of there, there can’t be much of a focus on writing…

That’s a great rant! We don’t get to see you rant that often; it’s nice.

Matthias: Have you ever read Gaddis? Wondering if you feel the same about him as DeLillo. (fwiw, I vastly prefer Gaddis, he’s one of my favorites, but I’ve never had the compulsion to read more than the two novels of DeLillo’s I’ve tried.)

No, I haven’t. It seems a bit of a mouthful to start in on Recognitions, which is the one I’ve thought about. Maybe I should?

Derik Badman- Coincidentally, I just got in the mail a copy of Martin Vaughn-James L’Enquêteur

I amazingly managed to get a copy of his self-published “The Cage” through inter-library loan. Sorry, Andrei, whereever you are, but I don’t think his language skills are anywhere near as accomplished as his drawing skills. A sample is right . Unfortunately another author whose visual skills greatly outmatch his language abilities, at least judging from that book. Hearing so much from Andrei about it on the TCJ mess board, I was quite surprised that I wound up feeling that way about it.

Here’s the link for “The Cage”:

http://thegreatgodpanisdead.blogspot.com/2009/12/cage-by-martin-vaughn-james.html

Matthias: The Recognitions is worth the mouthful. A great novel. It’s a lot about painting, which might be of added interest.

Caro: sorry for answering this late, but I had to go write my own pants text. My comment above wasn’t related to your take on _How to be an artist_ (great essay, by the way!, I said repeatedly in various fora that I don’t understand the logophobia of most comics readers; Dylan Horrocks said it perfectly: http://tinyurl.com/69n6uke). You wrote: “But because images are always present to themselves, visual art always conveys a strong sense of the moment.” I read “images” has meaning “all images,” not “the drawings in _How to Be an Artist_.” I suppose that you can privilege the larger picture in my link and say that, to itself this is the present; all the other images are holes looking at the past from my present. That’s even the most logical reading. But, I suppose that you also value counter intuitive readings. If we don’t privilege the larger picture we can reat it as a great deal of different times coexisting in juxtaposed spaces.

And, then, there’s also the role of convention, of reading protocols (which are related to what you called “from the perspective of the image” and I call “the time of fiction” in my essay _Ut Pictura Poesis_). This is what I call: the Bo Bo Bolinsky conundrum: http://tinyurl.com/5w6uqav

In the image above you can read a sequence of times (it’s the reading protocol of comics) or you can also imagine that no time at all passes and we are witnessing different simultaneous aspects of the same subject. Of the two what’s the right one from the perspective of the image? what’s the real time of fiction?

I think I’m also skeptical about the idea that there is a perspective of the image, or that such a perspective is always the moment….

I’ve been thinking about sound effects in comics for instance, which (especially in Japan where the writing moves towards calligraphy) seem like they end up being effectively part of the image…and so creating motion or a sense of time passing.

It’s true the image is literally not moving, I suppose…but text on a page doesn’t move either. Of course, one’s eyes move over the text…but your eyes can move over an image as well…especailly for example in the images Domingos provided.

Domingos– isn’t that Bolinsky page an illustration of what Scott McLeod calls aspect-to-aspect transition?

Alex: Scott McCloud is reading inside the comics protocol.

Noah: many comics theorists comparing comics to film don’t compare the panel to the frame, they compare the panel to the shot.

Caro–

Like Domingos, I apologize for the late response.

What you’re effectively calling for is for comics to be seen as a reading medium as opposed to being a predominantly visual one. There are any number of comics creators whose strength as a graphic artist is obvious without reading the work; there’s no reason why a comics creator shouldn’t be able to produce prose whose quality is apparent even to those reading it out of context from the comic–and which functions effectively within the context of the comic as well. There are certainly precedents for strong work of this sort. Campbell is one. Another, oddly enough (though not at the same level), is Frank Miller, whose mid-1980s efforts–The Dark Knight Returns; the Mazzucchelli and Sienkiewicz collaborations–are at least as driven by the prose elements as they are by their visual components.

Thanks for highlighting another question to be asked of comics creators when we read them. Hopefully, the attitudes in your piece will prove a productive challenge to them as well.

Belatedly, Noah, I can say with confidence that you would hate Underworld–and really shouldn’t even bother. White Noise is probably still your best bet, as it’s very funny, shorter, and not nearly as pompous. I like Delillo and Underworld, but it’s definitely got some pomposity issues. The baseball opening is great for baseball fans at the very least–but since that doesn’t describe you either, there’s no hope there.

Blood Meridian just made me thirsty…

@ Caro– The Heidegger bit—Is that from Being and Time (and if so, do you have approximate location?)–or from something else? Not shockingly, I didn’t make it through B & T in its entirety when I tried to read it. I made my students read “The Concept of Time” (a precursor text)–but I’m looking for a better excerpt of “Heidegger on time” to read and think about myself–and to pass on to the student populous.

Finally, and way belatedly– I think thinking of “words in comics” as prose (despite Caro’s definition) is kind of problematic. There are great examples of “mute” comics–with no words at all–and other examples which get a lot of mileage out of just a few words…because they interact with the images. Prose is really more (to my mind) a flow of words without the kind of extended and mannered pauses that you get with poetry and, I think, comics. Comics is not poetry (although it can approximate poetry from time to time)–but the use of words is not exactly prose either. I agree that often the “words” portion of comics is rarely “as good” as the use of words is strong prose writing (fiction or non–)–but I’m not sure that kind of writing is the best model for the “writing” portion of comics. Not that I have a great alternative, except to say that standards should, absolutely, be higher…and more time should be spent exploring, discussing, and working out where “words” DO work well in comics (as in Schulz, Herriman, and others)…as opposed to a monomaniacal focus on the way images work.

I think I’m just so tired of completely moronic vapidity perpetuated as “unassuming” that I don’t object to a little pomposity in the name of something actually worth thinking about. I also think we’re so used to mundane crap that anybody who doesn’t put on self-deprecating airs comes off as pretentious. But the self-deprecation is generally just as pretentious as the pomposity, and much less honest.

So I’d call Delillo arrogant before I’d call him pompous, and I’m not sure a little arrogance isn’t necessary to make work as worthwhile as what he produces. Contrast this, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C8m9vDRe8fw&feature=related with, say, anything you’ve seen on the David Letterman show lately…

I’m not ignoring you, Domingos and Robert, just haven’t had time to respond to anything I have to think about…

I think Campbell’s writing does work as prose, though, no matter what way you look at it. There are fairly long blocks of text, it all flows together (more or less…) It’s a lot more like prose than like poetry or a play script (presuming a play script isn’t prose….)

Eric, I don’t remember exactly but I can find the Heidegger again for you — I’ll pull it up asap this afternoon.

I think your definitions of both comics and prose are too limited here, unless you’re going to consider, say, writers like Ishmael Reed — or Patti Smith’s recent National Book Award winner — to be “not prose”. I think putting that kind of restriction on prose is stretching it a bit. There’s not really a strict precedent that prose can’t have mannered pauses, since, for example, formal political speech quite often does. You’d end up reclassifying a lot of historical prose as “poetry” if you enforce the definition you’re using — which I think gets into this problem I have with how this “unassuming” vantage point has colonized so much of our intellectual life.

It’s also not a question of mileage at all to me, just a question of style and, more importantly, range. The idea that comics CAN use prose and still be comics shouldn’t prevent other comics from not using prose at all. I suppose if someone wants to come up with another word for the umbrella term that includes the larger range, I could get ok with that, but “comics” is the best we’ve got at the moment… Maybe something like “imagetexts”, but wow, how pompous is that!

Well, Wikipedia, that sage old source of common wisdom, says film is prose, so I’d presume most theatre would be. Unless it’s blank verse…

I just really don’t support reinventing the wheel here in order to come up with a 3rd term that JUST applies to comics. You can use BOTH verse AND prose in comics — just like you can everywhere else.

There is an academic journal called “Imagetext” which is mostly about comics–so you’re not being any more pompous than people are already being about it! I agree, that Campbell does partake of “prose” and that comics CAN do so (Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home is another very prosy comics work), but comics’ use of words is not limited to such traditionally prosy prose. Delillo’s early work balances the pomposity with some interesting philosophical propositions and some wickedly funny takedowns—I think his later stuff (and Underworld and post-) doesn’t really carry the balance quite so well. Like you, Caro, I’m not above a certain amount of elitism–but if it’s a hollow kind, then it’s not really at that worthwhile. I’m a big fan of the insufferably pompous Salman Rushdie, though–so, there you go. As for Letterman, I used to find him quite funny, frankly–although I don’t think I’ve seen his show since before the move to CBS. I’m well into dreamland by that time of night…

I guess calling comics or film prose is fine as long as we’re not judging them by exactly the same kind of standards as a novel, short story, or written biography. Images can, and should, carry plot, theme, character, themes, etc. in film and comics—meaning there are lengthy breaks in the “prose” (or it may not even exist)–and the film/comic can still be good or even great. Crappy prose (or no prose) will obviously kill a text that is 100% (or near enough) prose—but one can imagine a comics text of several hundred pages with only a couple of lines of (prose) dialogue. If these are fairly innocuous or simply straightforward, it won’t kill the text. (If there really bad and cliched, I suppose they might)–So–prose can be important to comics (or film), but it doesn’t have to be– Still–yes–the quality of writing in comics is often cringe-inducing (of course the quality of prose in much fiction is also cringe inducing)…

pardon the typos…

In comics, the drawing IS prose. Case closed, next.

Domingos:

“Alex: Scott McCloud is reading inside the comics protocol.”

What does that mean (if it means anything)?

Honestly, Alex, you know that “drawing is prose” is a metaphor. And not even a metaphor that meaningfully describes the work under scrutiny here. Sheesh. Try actually reading the comments thread before you strike a pose of resolving it, please.

Eric, I completely agree that comics’ use of words shouldn’t be — and isn’t — limited to prose. Franklin Einspruch’s Pears uses poetry; Feuchtenberger makes image-poems to accompany prose-poems. Both are favorites of mine. I think they, and Fate of the Artist (another favorite) are all marvelous examples of different kinds of comics.

The problem I have with the “drawing is prose” attitude toward comics is that it’s essentially confusing medium with genre. There can be lots of genres of “comics” — including one where drawing functions exactly as prose. But comics is still bigger and broader than any single category (at least, until someone makes a compelling argument that imagetexts really is a better umbrella term for anybody other than academics…)

I also think there are two issues here, which the comments thread really brings out quite nicely: there’s the question of the quality of prose, indeed, and it is essential — but there’s also the idea, which Sean brings out eloquently in his initial comment, that eschewing words and asking the drawings to do prosaic work, particularly prosaic work, is the highest aesthetic standard that comics can be held to. I think the latter perspective is much more destructive than the former, because better editors and critics and even just a little more emphasis on writing in training would go a long way to solve the former. The latter, however, is an entrenched attitude, with its own history, that to no small extent causes people within comics to devalue prose writing — in comics and otherwise. I think that attitude will be much harder to explode.

Oh, one more thing on medium as genre: I tend to find the types of genres that are currently used to describe comics (like memoir, superhero, even “art” or “literary,” etc.), genres which allude to the narrative content (and often target demographic) of the comic, extremely unsatisfying. I think although “comics” is organized structurally at the highest level into an umbrella category with sub-genres, similar to the way we think about “novels,” the genres of comics just aren’t parallel to the genres of novels (literary, romance, western, SF). At that classificatory level, the materiality and technical attributes of the comic are extremely important, and “genres” patterned after the types of categories used in visual art feel more appropriate. So things like “image poem” or “illustrated novel” or “drawing as prose,” although surely we could come up with snazzier terms.

I suppose that you know that “imagetext” is a term coined by W. J. T. Mitchell? http://www.highbeam.com/doc/1G1-63859271.html

Comics reading protocol: the reader assumes that a certain amount of time passes between the panels.

That doesn’t persuade me it’s not an excessively academic term, Domingos! (I did know it; I really like the journal…it’s open source…hurray for them.)

Caro:

“Honestly, Alex, you know that “drawing is prose” is a metaphor. And not even a metaphor that meaningfully describes the work under scrutiny here.”

No, it is not a metaphor. In comics, drawing takes over the function of prose. Everybody knows that, Caro.

What you said initially is, in point of fact, a metaphor. As opposed to a simile, which is basically what you transpose it into when you restate it. “Drawing is prose” is a metaphor. “Drawing is like prose” is a simile. “Drawing takes over the function of prose” = drawing behaves like prose = loose simile.

So your original statement is either a metaphor, or it’s a literal absolute equating two media, which is ridiculous. Drawing is obviously not literally “prose.”

But the weaker simile is factually wrong too. Prose is not a functional concept; it’s something closer to a medium. And like most media, prose doesn’t have a singular function; it carries myriad types of work.

There are a great many ways in which drawing doesn’t behave like prose, such as the one Eric mentioned with regards to continuity. The manipulation of prose abstractions is another — literary device is not a one-to-one. In the present work, drawing doesn’t take over the narrative function — it mostly takes BACK the imagery work that prose does so much less natively.

So the way in which the various types of work that prose can do in fiction (as well as the work that images can do in visual art) gets re-distributed between the words and images in comics is an artistic choice, not an artistic absolute as you imply, or even an axiom. I thought the comments from Derik and Sean earlier made this pretty clear.

I can take a story such as Mark Twain’s “The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County” and render it as a silent comic quite easily. My drawing would replace the prose and its functions.

Alex, it wouldn’t. The Jumping Frog is actually a great example of why. It’s a story-within-a-story, and a huge amount of the point is the humor of the dialect retelling.

“Thish-yer Smiley had a mare the boys called her the fifteen- minute nag, but that was only in fun, you know, because, of course, she was faster than that and he used to win money on that horse, for all she was so slow and always had the asthma, or the distemper, or the consumption, or something of that kind.”

You can’t do dialect in pictures. You could get the narrative (what happened after what) but the prose dialect — which is perhaps even more important than the events in this story — would be lost.

I deliberately chose that story because its prose is so rich. My point isn’t that all prose can be converted to pictures, but that drawing in comics functions as prose.

But drawings in comics can’t actually convey dialect. Conveying dialect (or voice) is one of the main things that prose does. Images can’t do that. So they don’t function as prose.

They can pick up some of the functions of prose (like narrating events) but not others (like conveying dialect.) And then they can do some things that prose can’t.

If you did a silent comic of jumping frog, your drawing would replace the prose and some of its functions. But the drawing wouldn’t be prose. Because of that, because the story is very specific to its medium, you would lose a lot of what makes the story the story. You’d lose the prosody. You might gain something too…but what you’d gain would be because of the specificity of comics, not because of the specificity of prose.

Like Caro said…to say comics is prose is a metaphor. Comics and prose are two unlike things. You can compare them because language is like that. But comparing them doesn’t make one the other.

I don’t even really understand what you think you gain by claiming that one is the other. If comics are just prose, why bother with comics? Most people are more comfortable with just text; it’s easier to reproduce. If the experiences are the same, it seems silly to mess around with both. It’s only if comics has something different to offer — if it’s not prose — that it can justify itself as a separate medium.

A utilitarian argument!

I think we have a generational split here. remember reading all those Man-Things, Noah? Didn’t you ever think about the endless captions and yakking, ‘Will you shut up and get on with the story, such as it is?’ It has been an object of the last thirty-odd years to avoid telling, and to show– graphically.

I don’t think anyone has a special problem with comics showing graphically. The point is just that showing graphically isn’t the same thing as prose…and that, as long as we’re going to use words, it seems like a good idea that they should be well written.

The problem with man-thing wasn’t that there were too many words. The problem was that the words were written badly (and one of the ways they were written badly is that they were over-verbose.)

Perhaps the pendulum is swinging back to garumousness, though, with words doing the work of pictures…

Oh, and i disagree that drawing has no dialects. Look at manga, look at Hergé!

The idea of a “dialect” in drawing is also a metaphor. Alex, you might want to read Lakoff and Johnson’s Metaphors We Live By to get a better sense of how this works.

Words and pictures don’t “do” each other’s work. They do different work, and they do the same work differently. One of the things that holds comics back in terms of their artistic achievement is that most people in comics are so much more sophisticated about the images than they are about prose (if not actually narrative) that they automatically move to this kind of metaphorical equivalence rather than maintaining the kind of strict differentiation that’s necessary for really complex formal structures. This is why the “drawing is prose” approach is so incredibly bad for art comics: it’s not an assertion of a medium-specificity proper to comics; it’s rather the rejection of any medium-specificity proper to verbal language.

Yeah…saying that Herge has a dialect is just saying that he has an individual style, which is true, but has little to do with the dialect writing Mark Twain is working with.