(Two Comics by Stella So)

The cartoonist, Stella So, is the last entry in Chihoi and Craig Au Yeung’s 2007 survey of “25 Years of Hong Kong Independent Comics” (Long Long Road) — a brief stopover for this small but vibrant scene.

Au Yeung’s blurb at the back of the 2010 reissue of So’s Very Fantastic describes her as one of a new generation of born and bred Hong Kong cartoonists; an artist who has a singular eye and feel for the life and character of that city.

The book in question is an early sign of that promise. It documents the entire process through which she created her 7 minute animated film of the same name which won a gold medal at the 2002 Hong Kong Independent Short Film & Video Award (IFVA). It is in many ways the more interesting project of the pair, revealing her working methods and the components which make up her art.

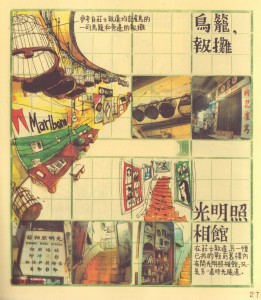

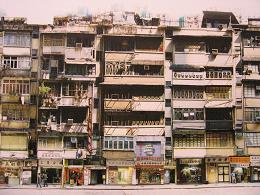

Very Fantastic was done as a graduation project from the Hong Kong Polytechnic University in 2002, and describes the fading world of old Chinese tenements (tanglou in Mandarin). Her travels through the corridors and byways of these old structures make up the bulk of the book, combining sketches, photos and description in a kind of careful collage. Hence the distortions in this view of a row of bird cages…

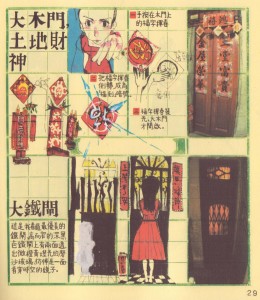

…and this sketch of a dark iron door crowned with frosted glass funneling a warm orange intensity.

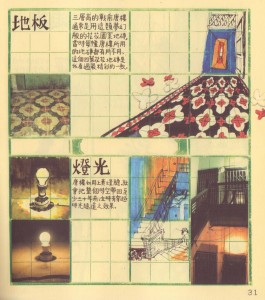

So’s book is not only a record of grizzled castaways — faded electronics, old furniture, and tiles — but also a collection of chromatic reminiscences, not least from the fiery glow of the humble incandescent light bulb. The quality of light in a stairwell is noted at one point and is seen to transport that space back 30 years.

The most vital elements collected during her expeditions are selected and assembled into a whole which is curious yet evocative.

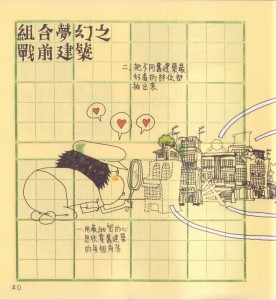

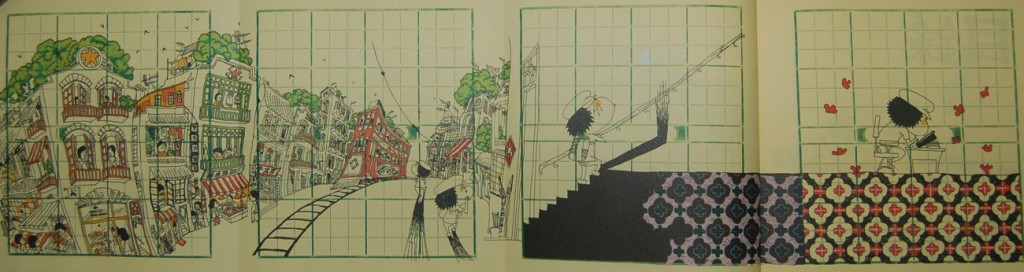

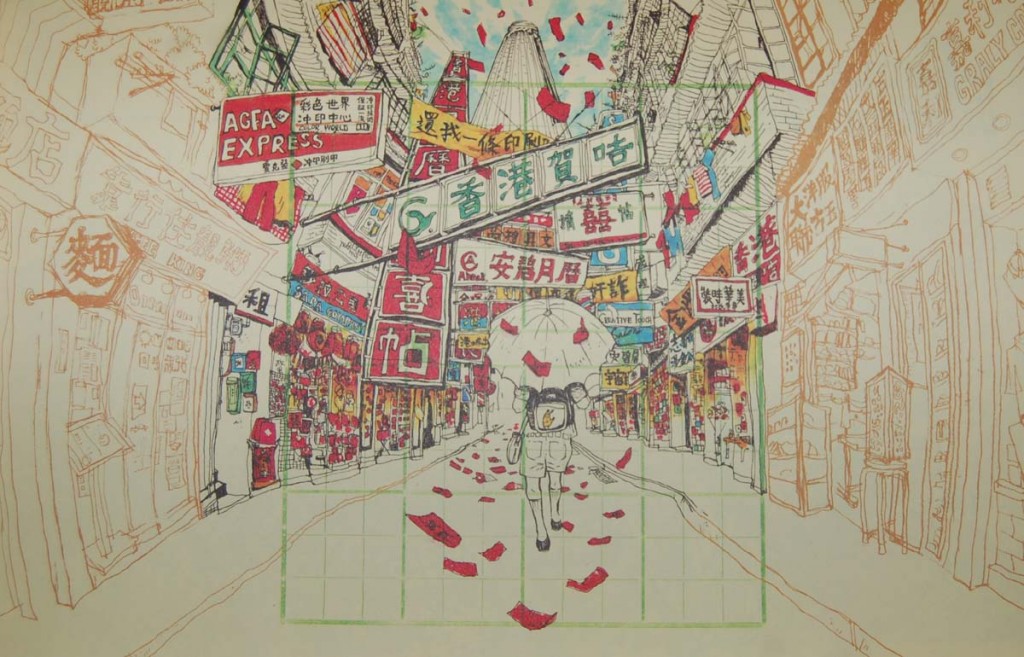

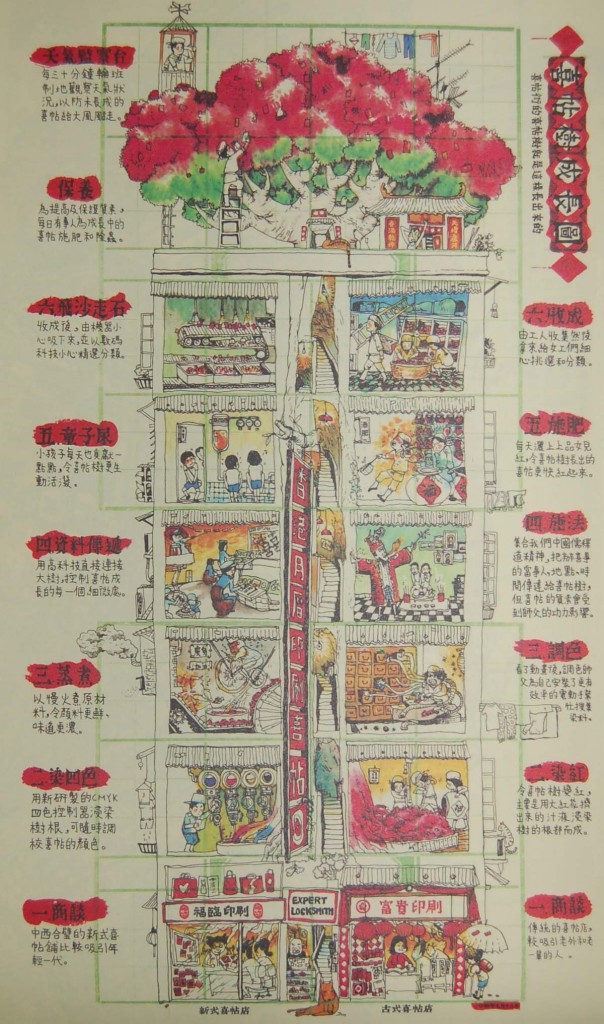

The rest of the book chronicles the process of character design, sound recording and animation; every page formulated on a grid design which is typical of practice books for writing Chinese characters. These don’t merely act as guidelines but also as flexible panels to which she fits her sketches. As such, the book becomes not just an exercise in cartooning and the deployment of the imagination, but also one of using the practical qualities of the page. The final shot of the cartoon shows the protagonist walking down a staircase lodged in the thin gutter between the four rows of calligraphic squares, the paper now turned on its side to give a long vertical space instead of a horizontal one. The paper lodges the proceedings firmly in a Chinese past, the fading green lines hardly being the stuff of modern printing (and modern Hong Kong). A reasonably common practice in the East, and one which is not unknown even in America (for example, in the work of Lynda Barry).

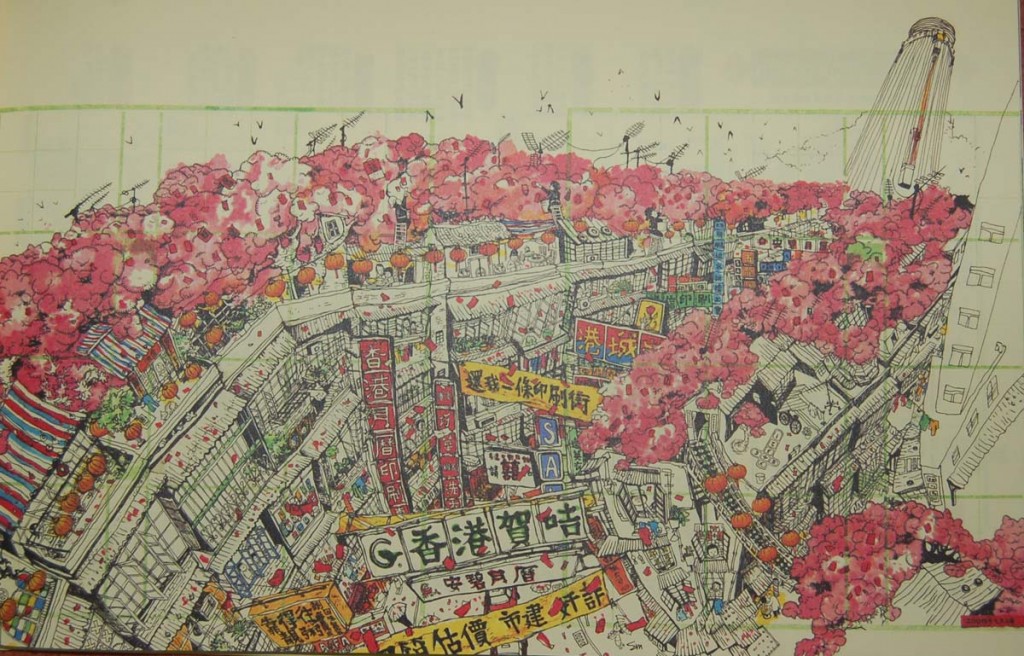

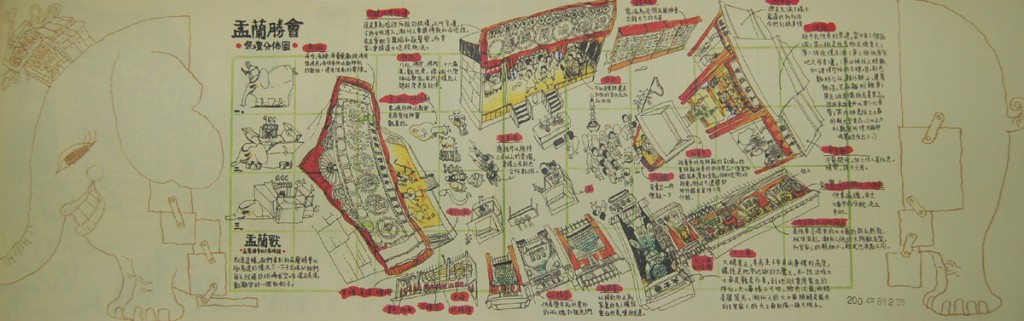

The large fold out panoramas which inhabit the first section of the book are not only functional in design, but calculated to draw readers into the centuries old tradition of Chinese scroll painting.

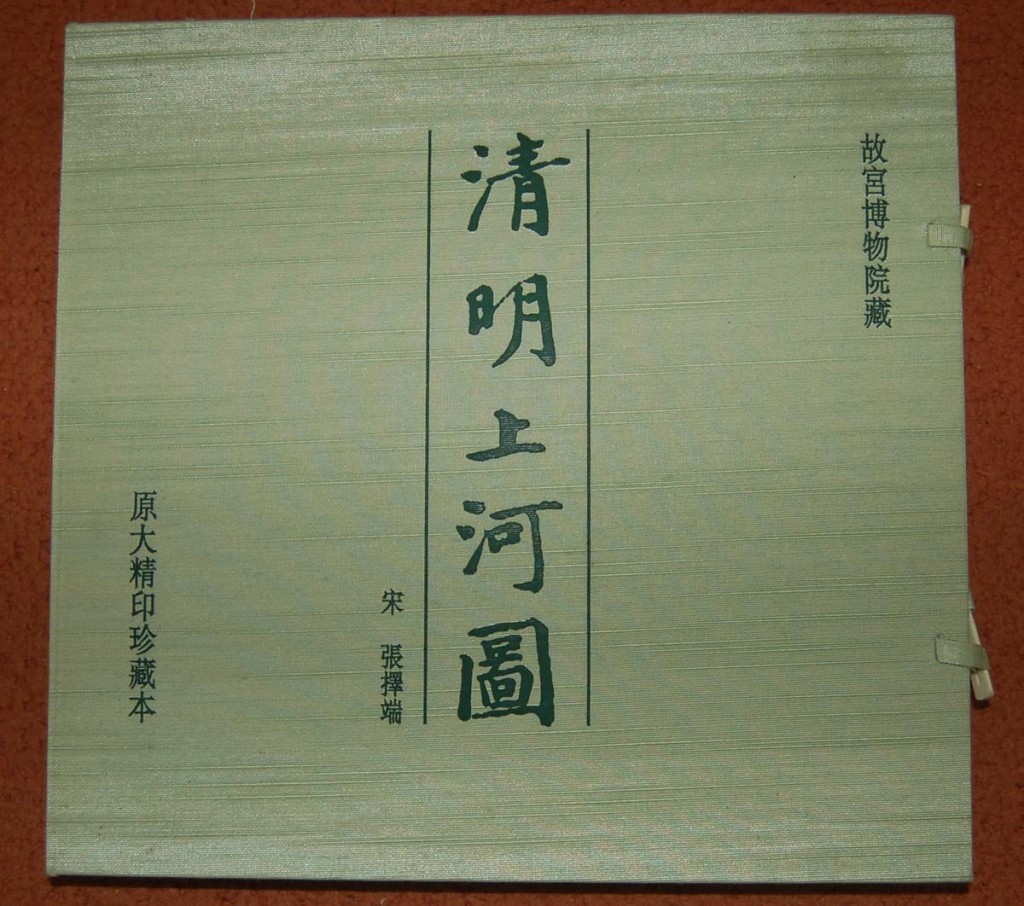

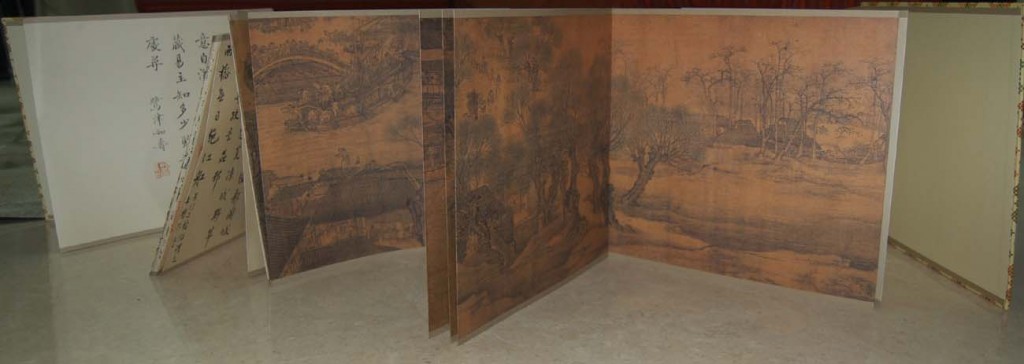

The most famous example of this must be Zhang Zeduan’s Along the River During the Qing Ming Festival (QingMing Shanghe Tu; 11th-12th century) which, to this day, is reproduced in scrolls and collapsible books like the one shown below.

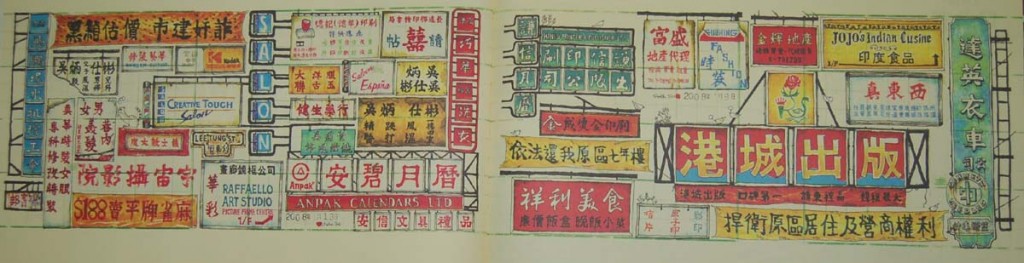

The ultimate expression of So’s longing can be found in City of Powder -Vanishing Hong Kong, an oblong-shaped book of illustrations and comics published in 2008. So is fascinated by the sensory environment of the city, and the chapter titles of this memoir reflect the colors, smells, and sounds she experienced during her excursions. As with her earlier project, the drawings here are an amalgamation of the real and the imagined; a compression of time, place, and meaning.

A lyrical article at Honey Pupu is as detailed an analysis of So’s art as you will find online. The author doesn’t see her as any sort of conservationist — she hasn’t the influence or the training for this — but as a nostalgist, the poetry of whose images convey something of the truth of memory. These comics are free from narrative and the flow of time; the saturated hues and imaginings not suggestive of history, but of something instinctive and almost incontrovertible.

The chapter describing “Wedding Card Street” could be described as a burst of synesthesia captured on paper. The first page shows an accumulation of sensory and emotive detail harvested from various points in space and time, all focused on the central area of the artist’s work sheet.

The next two are mythical constructs depicting flowering Wedding Card trees and the romance of manufacturing.

So is especially concerned with the latter aspect of city living, and dwells at length on the preparatory steps involved in cooking a bowl of noodles at a favorite noodle stall, and the logic of the signs which litter her vistas. The building cutaways reveal a progress from the joys of union to the intermittent pleasures of old age. It is not a story with a happy ending. The first drawings in this series are dated 2004, the last showing beshrouded buildings, withered trees, and gaping maws is from 2008, the last act in a place now consigned to dust.

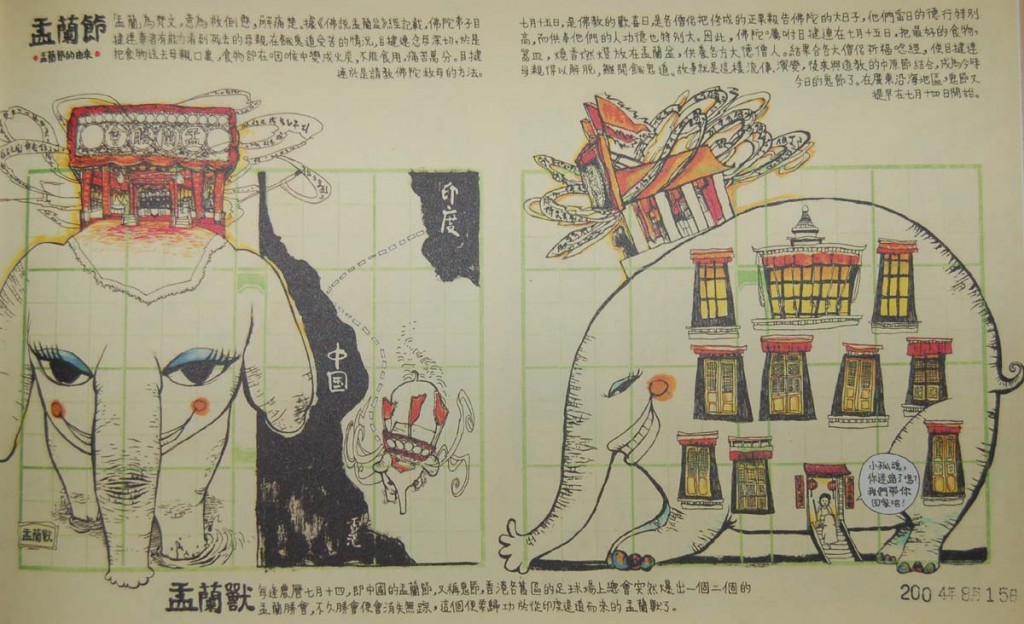

City of Powder ends with the origins and customs of the Chinese Ghost Festival; a not surprising conclusion in view of the theme of So’s book. It begins with a description of Maudgalyayana’s (a disciple of Gautama Buddha) quest to liberate his mother from hell where she has been transformed into a hungry ghost, a creature in a perpetual state of longing due to its inability to consume any food. The food offerings which are sometimes found at various houses and temples during the Ghost month relate directly to Buddha’s solution to this dilemma. The Indian elephant is a reminder of this cross-cultural fertilization; the dialog between the little girl lost and the boy, a not so subtle call to remember tradition amidst modernity.

When the boy asks the girl how she came to be lost, she replies that she couldn’t find her way home because of the rapid changes to the city. The ceremonies and offerings which make up innards of the mechanical pachyderm are reminders of an urban past, a ritual of rebirth which recalls Maudgalyayana’s efforts to ensure his mother’s reincarnation.

This is awkward and yet so charming in its delivery that it becomes convincing and emotionally satisfying; much more so than some itinerant stories concerning the destruction left in the wake of the Three Gorges Dam that I’ve seen. Because the sadness of displacement, and the sweat and tears of the dispossessed are not the only reasons why we cherish a hard but now desolate past. The artist of City of Powder captures that rose-tinged spark of remembrance, and while her portrait is sometimes tinged with sentimentality, it is one that should not be casually dismissed.

Further Reading

A profile of the artist in Chinese.

An interview with Stella So at HK magazine.

Commercial Press online where the comics of So and her contemporaries can be purchased.

The “real” Wedding Card Street (culled from Google images):

Thanks for this wonderfully informative post! I’m in Shanghai currently working through the history of manhua (read: drooling over Feng Zikai) and am definitely looking forward to seeing how So and her contemporaries are working within an “independent” scene so to speak when I get to Hong Kong in June. On a somewhat related note, another HK artist I found a few volumes of in Taipei goes under the name of Kicklamb (http://kicklamb.com/news.html) and I found his stuff to be all over the place but mostly wonderful. Are you familiar?

Also, I picked up some Abi Jian in Taiwan because of that article you wrote awhile back and I think I enjoy it a lot more than you seemed to have.

I didn’t know you read Chinese, Nadim. What are you doing traveling through Taiwan, China, and Hong Kong. Business or holiday? Did you manage to find a complete edition of Feng Zikai in Shanghai? Much cheaper to get the books while you’re in China even if you have to lug them around.

Yup, I’m familiar with Yang Xuede (that’s in Mandarin not Cantonese which would be more correct). There are some who consider him the best of the current (previous?) generation of HK indy cartoonists. “How Blue Was My Valley” is his most famous work, and it has been translated into French I believe.

Abi Jian is fine for what it is. The first volume is pretty draggy though.

At least to my eyes, these look as much like picture books as comics (which is not a bad thing at all.)

They are beautiful, challenging.

Nadim, so you’re back among us…cybernetically, at least!

You may have to work to adapt your Mickey post to the new format…

That occurred to me as well (re: comics vs picture books). Both the publisher and the artist seem willing to call them comics though. There’s definitely cartooning involved, as well as panel work, narrative (on the opposite pages) and sequence. So it would be hard not to call them comics. Nadim brought up Feng Zikai. To the untrained eye, some of his illustrations/drawings might look like traditional Chinese brush painting as well. But they’re called comics (and cost a pretty hefty sum to purchase in the original).

I don’t mean to deny their comicness. More just musing on how I wish more American comics straddled those approaches.

I’m in China as part of my ongoing research grant to “follow Tintin’s trail” and the comics that were created in those places contemporarily to Hergé. I do not read Chinese (a fact which I’m painfully aware of as I wonder the streets) but I have some money for a translator and friends here and there who help me bargain for the non-bookstore comics.

I’ve come up against the comics vs. picture books distinction a lot since being here. One of my friends was surprised how excited I got over what they considered picture books from the 70s, but I saw them as comics with just one panel a page.

@Alex I am back! I stayed away from the computer for much of my time in Taiwan in lieu of more travelling. Now that I finally settle down again I find the HU is beautified! I’ll get around to adjusting for the new format I’m sure…

Which begs the question…why? Would it really make them any better? Strangely enough, a number of Hong Kong and Taiwanese “alternative” comics fall into that category. Shaun Tan’s (an Australian) The Arrival and Tales from Outer Suburbia fall into the category you mention as well.

Well…I think in general American comics suffer from their insularity in various ways (stylistically, in terms of audience, etc.) Reaching out to picture books seems like it would be one way around some of those issues.

Cross post. The last reply was to Noah.

Nadim: That is serious research. Good idea to get a Chinese local to bring you around so as to avoid being cheated at certain outlets. Seriously. There’s one price if you speak Chinese and another if you don’t. That’s my experience anyway.

Some of those picture books are great. Check out the collected Romance of the Three Kingdoms, available in handy cheap boxset versions as well as collectible box-carton sets (very heavy). It’s probably the height of that art. The classic ones are not from the 70s, they’re from the 50s-60s (I think; I have to refresh my memory). Very similar to what you get with Prince Valiants actually but with the occasional word balloon.

This is amazing. A-maze-ing.

This is great! Speaking of the Three Gorges Dam check out Liu Xiaodong’s paintings.

Heh. Nadim, you’re actually turning into Tintin.

While you’re at it, get your translator to decipher some of the background text in ‘The Blue Lotus’.

I suspect the Chinese editions have changed it, as there were a number of pro-Chiang Kai-Shek posters on the walls. Chiang, btw, was a huge fan of Tintin, and invited Hergé to move to Shanghai…