I realized about halfway through a recent interview with Cult Youth founding member Chairman Ca that I was asking the wrong questions. I was nearing the end of my stay in Beijing when I finally got a meeting with Ca, who was seeming more and more like the leader of the only real contemporary comics’ collective in China. In him I sought proof that Chinese comics (or “Manhua”) not only had a present, but a future; a future that would create a discursive political/social space for young critics like it had for so many countries before China. In him I found not the leader of a comics’ revolution, but a very talented dude who likes to make comics about Zombies.

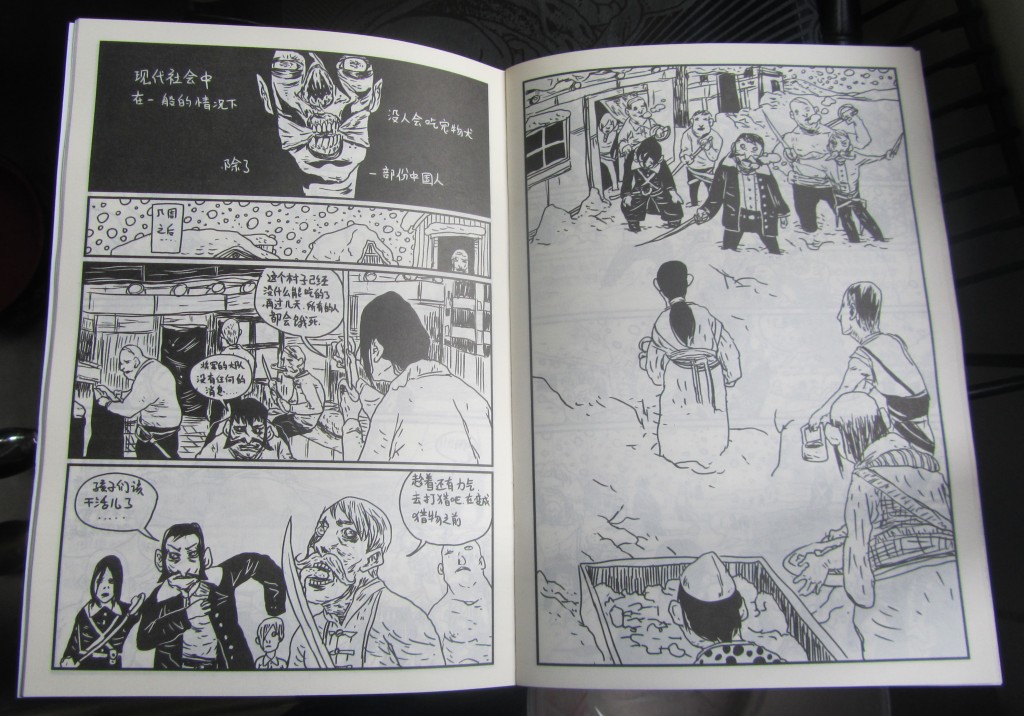

Pages from Chairman Ca’s Zombie Pie

But before we discuss the salience of Cult Youth (CY), it is important to understand the larger comics’ community (or lack thereof) in which they operate. To put it simply, besides CY and a few rare exceptions, there aren’t any contemporary Chinese artists producing comics. However, this doesn’t mean that Chinese people aren’t avidly consuming comics on their iPhones and knock off iPhones alike. You see, the comics that are popular in China aren’t made in China, they’re translated Japanese imports. If you are remotely familiar with the history of China-Japan relations — from The Rape of Nanking all the way to the Diaoyu Islands — hearing that China openly embraces Japanese culture might appear contradictory to popular opinion. And for scholars of Manhua’s history (which you are about to get a primer on!), the reality would seem even stranger. As I’ll explore today, it somehow works that the culture which has youths actively devoting weekends to reading translated Japanese comics is the same culture where you can still read bumper stickers like this:

The history of Manga and Manhua have long been intertwined. The shared heritage should be evident from the name “Manhua” itself, a term adopted by Chinese to approximate the name “Manga” that Japanese caricaturist Hokusai Katsushika famously gave to his depictions of everyday life back in 1814. For a long while after that, Japanese held regional dominance over what was produced under that term, including work like Li De’s strangely Western-like The Rat’s Plaint in 1891. But as Japan-China relations soured under the weight of Japan’s imperial tendencies in the early 1900s, Manhua and Manga saw a clean break.

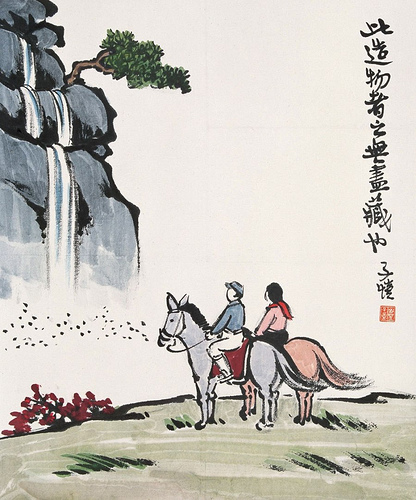

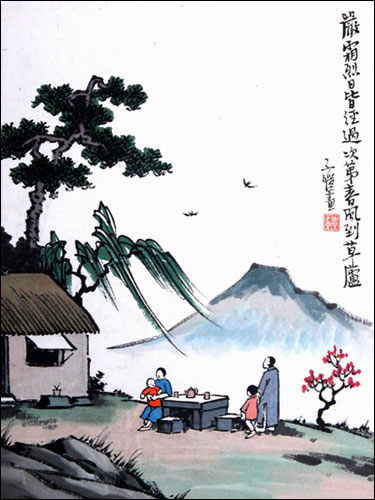

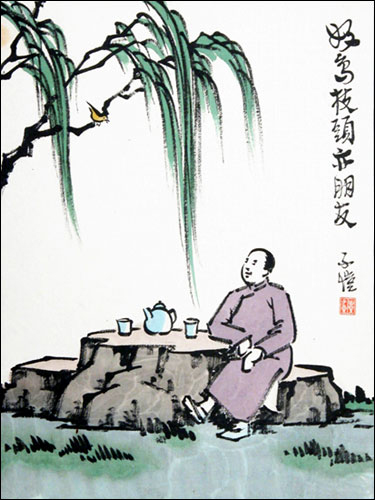

That clean break is perhaps best exemplified in the clear lines of Feng Zikai, who emerged in the early twentieth century as China’s preeminent comics artist. According to the wonderful Hong Kong Comics: A History of Manhua by Wendy Siuyi Wong, it was Zikai’s first published collection of cartoons, Zikai Manhua, in 1925 that better defined “Manhua” as a distinct art form in Chinese society. Through the work of Zikai, Manhua transformed from a loose pan-Asian signifier to describing a specialized Chinese art form with a common aesthetic. I’ll pause here to share some of Zikai’s art, which understandably galvanized a whole nation to define a term around it:

These Feng Zikai’s illustrations come via Cultural China and China Online Museum (where I encourage you to take in many more pieces)

Before long, Manhua became a venue for the political as the nation grew increasingly resentful of Japan’s growing regional dominance. In 1927, the Shanghai Cartoon Association — the first cartoon society of its kind in China — formed as a gathering point for a growing roster of Manhua artist. Founding members included Ding Song, Zhang Guangyu, Lu Zhengei, Wang Dunqing, and, of course, Feng Zikai. “The association helped to solidify the loosely organized network of artists that made up the comics industry,” argues Wong in HK Comics, “and it encouraged efforts to raise the quality of its products.” Indeed, the Chinese artists not only used the organization to better their art, but through it explicitly defined Manhua as an art-form and a nationalistic enterprise. Like most nationalistic enterprises, Manhua came to define itself in opposition to other nations; namely Japan. At the Shanghai Animation and Comics Museum the association’s emblem hangs proudly near the entrance with an explanation:

“The association’s emblem is a Cartoon Dragon, representing a caricatured dragon awakening, taking off, determined to fight for the future of the homeland. Members of the association played a leadership role in the cartoon circle at that time, acted as hardcore force in cartoon creation and initiated many periodicals.” (Text from Display)

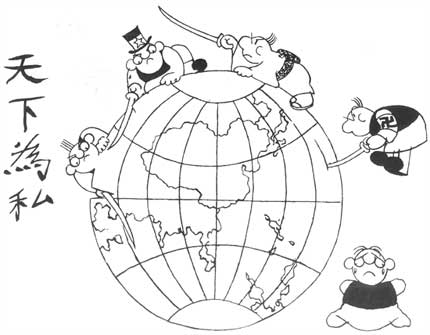

The dragon awakened within the pages of Chinese cartoon magazines and newspapers alike in the 1930s, determined to fight for its homeland at the start of the Sino-Japanese War. In this especially heated time, many artists became popular for creating anti-Japanese characters. One such artist was Huang Yao, who developed the character Niu Bi Zi. Here is perhaps Yao’s most famous cartoon, which depicts Niu Bi Zi (as China) helplessly crying in the wake of the West’s selfish gutting of the world:

Image via Lambiek

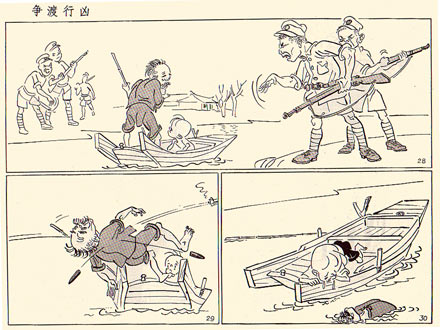

Then there is Zhang Leping, one of the most revered Manhua artists of his generation who is best-known for creating the cartoon character”Sanmao.” For decades the very popular Sanmao represented the struggle of the Chinese people and helped expose the cruelty of occupying Japanese forces. Take for example this typical anti-Japanese Sanmao comic, which shows the Japanese soldiers as senseless and ruthless killers.

Image via Lambiek

The members of the Shanghai Cartoon Association stoked the nationalist flame of China with hatred of Japanese, a fuel source that the PRC has repeatedly used through history when needing to drum up nationalism quickly. The work of these mainland artists from the 1920s until the early 1950s distinguished Manhua from Manga, seemingly putting the two countries in a race for regional dominance in the world of comics.* Today, it takes just one foot inside a Manhua store in any Chinese city to see that the two-way race was won by Japan long ago.

This all leads me back to Cult Youth, an independent Beijing-collective who at first blush looks like a 21st Century incarnation of the Shanghai Cartoon Association. I discovered Cult Youth through this short documentary of them floating around online:

(Click For Video)

Just like the Shanghai Cartoon Association did in the 1920s, Cult Youth have formed a community built around making (and re-defining) Manhua. A productive community at that: since 2007, Cult Youth has self-published three jam-packed collections of work that they sell online. They come across as a rare creative force in an otherwise stagnant market, willing to embrace “DIY” touchstones and break a few rules in the name of putting out relatively provocative comics. “If you were not born in the 80s and couldn’t decode the plots, then give up! This is not for you!,” reads the CY manifesto at the video’s start, “this is a new generation free of the reasons and worries of the past.” In the context of mainland China this bold self-determinative statement feels radical (at least to an outsider like myself). Which is why when I finally met founding member Chairman Ca I was expecting him to embody the language of young revolutionaries, when in reality he was much more modest about his ambitions.

Chairman Ca in his studio.

In my interview with Ca, he politely deflated my suggestions that maybe China was on the verge of a new comics renaissance. Instead, he explained that for him comics are more about a group of friends having fun on the side of their day-jobs, not a potential career path. Ca is an immense talent who has been actively making comics and other art since his days in university, yet he doesn’t keep a portfolio because he doesn’t feel like he needs one. When I asked him about the influence of luminaries like Feng Zikai or where he sees himself in the larger continuum of Manhua he gave me an unexpected answer: “Growing up here we come into contact with more Japanese comics. Only after the Internet became prevalent did we learn about European or North American comics.” Which is to say, the major influences of Ca and Cult Youth’s creative aspirations are not found in the history of Chinese comics, but downloaded copies of R. Crumb and translated Manga. Where the forefathers of Manhua defined themselves in opposition to Japan, Ca represents a generation that defines themselves in collaboration with Japan.

According to Ca the prevalence of translated Japanese comics in today’s market arose because while Manga was establishing itself as an industry in 70s, 80s, and 90s, independent comics were ostensibly made illegal in mainland China. Meanwhile, while the mainland had run dry of original content, Japanese publishers responded to a continued demand for comics in Taiwan and Hong Kong by translating Manga series into Chinese. Hence, Ca and his peers grew up in the mainland with the only new comics available in their language being pirated Manga translations from Taiwan and Hong Kong. Ca’s reference points are then Western reference points: Rockabilly was his first musical love, Zombies are cool, and he identifies philosophically as a Existentialist. For Ca, the fact that Japan is the chief-purveyor of comics in the region isn’t a cultural defeat as older generations would understand it, but simply a reality.

“The industry does well there, it has certain principles and successful cases. It’s easy for young people to turn themselves into that comic industry because it’s an established business,” says Ca of Japan’s Manga market, “For a Chinese person to make a living out of comics it takes a lot of resolute determination to get there. Maybe too much.” Ca’s stance exemplifies a generational shift in Chinese society in the wake of Mao. A generation who now unabashedly embraces Japanese culture through Manga is perhaps the logical extension of Deng Xiaoping’s market-oriented reforms from 1978 onwards: for better or worse, China shifted from a self-contained market to a interdependent player in the world’s economy by opening up. It appears that in the last twenty years the definition of “Manhua” has itself opened up. No longer in a vacuum where it is used as a political tool to encourage nationalism, Manhua is now a term that encompasses a rich history, a translated marketplace, and a few stray youths.

—-

* The 1950s marks the formation of the PRC by Mao, and the point where innovative Manhua fled with many Chinese to Hong Kong. While Manhua continued in the mainland during the twentieth century, it was mainly in a bastardized and government sanctioned-only form unlike its early creative years.

A very special thanks to my friend Alec Sugar who served as my fearless translator during the Chairman Ca interview.

And one more Zikai for the road:

fascinating article. Great information about Chinese comics! I guess I learn something new everyday!

Does the term “manhua” also cover Hong Kong comics, which, from what little I’ve seen of them / read about them over the years, have a very different and much more Western-influenced history?

Yeah, back in the ’80s there was a whole raft of Hong Kong martial-arts titles translated, with title like ‘Drunken Fist’– art closer to the Filipino stuff than to those manhua. A comics equivalent of the Run Run Shaw empire in cinema…

Great article, and I hope it opens new pespectives to the “west” for Chairman Ca & co.

Er, you should understand, as a native Chinese, this article would inevitably have many places that make me raise my eyebrows.

But it’s still nice to see people like Cult Youth and Feng Zikai being mentioned in the same article.

I’ll try to add some context. I’m an idiot, and this is just what I can think of now. Commentary in the order of things appearing in the article, not importance.

1. Manhua

I always have reservations about coining English words like “manhwa” and “manhua” after “manga”. The Japanese comics occupy a unique and extremely prominent space in the Japanese society, and support a massive industry, so even if they don’t really require a unique English word for them, they at least deserve it better than Chinese or Korean comics.

But this is just my pet peeve; I understand the creation of these words is partially driven by the need of marketing.

And there seems to be no reason to not include Hong Kong and Taiwanese comics into the definition of “manhua”.

>Hong Kong martial-arts titles… art closer to the Filipino stuff than to those manhua

The art style of the Hong Kong fighting comic industry is directly influenced by artists like Ikegami Ryoichi and Hara Tetsuo. I know nothing about Filipino comics, do they take the same source of inspiration?

2. The Chinese attitude towards Japanese pop culture

I’m afraid this has nothing to do with the historical relationship between Chinese and Japanese comics.

Some important details that wouldn’t be shown in a general outline of history:

In 1978, through Deng Xiaoping’s (you must have heard of this name) effort, Japan and PRC signed the Treaty of Peace and Friendship, which is still in effect. This treaty created the “honeymoon period” of Sino-Japanese relationship. During the late 1970s to 1980s, China imported not only technological knowledge and material goods from Japan, but also its cultural product: movies, soap operas, and anime such as Astro Boy and Kimba the White Lion. This era have ensured the urban Chinese to have at least a basic familiarity with Japan.

(PRC’s hukou system segmented its citizens into urban residents and rural residents. This system is in the process of being abolished, but still has great effects on people’s lives. And unfortunately, the rural population, which is China’s silent majority, has so far played no part in the history of Chinese comics.)

During the early 1990s, an entire generation of urban Chinese get to grow up in families that can now afford TV sets. Compared to now, there was relatively very little regulation about what can be shown on TV, and the children’s time slots are filled with foreign cartoons, imported at extremely low prices which were practically gifting. They also have access to volumes upon volumes of manga pirated from Hong Kong and Taiwan (which are in turn pirated from Japan; some of Taiwan’s pirate publishers will eventually turn legitimate).

As I understand, similar things also happened in Taiwan and Southeast Asia. Anyway, their effect on what would become China’s middle class is profound: today in a large Chinese city, you can hardly spend one day without seeing a car with some Transformers sticker. Transformers is of course not a purely Japanese product, but the most influential icon of this pop cultural cocktail, of which anime / manga are an important component.

Hokusai didn’t coin the expression “manga,” that’s a myth.

3. Feng Zikai studied in Japan as a young student, and was influenced by Japanese artists of that period.

4. a typo: it’s “Huang Yao”, and the links to the Huang Yao and the Zhang Leping pages are backwards.

5. “…innovative Manhua fled with many Chinese to Hong Kong. While Manhua continued in the mainland during the twentieth century, it was mainly in a bastardized and government sanctioned-only form unlike its early creative years.”

To me this reads like a gross oversimplification of the 20th century Chinese intelligentsia’s relationship to PRC. Many truly believed in, were sympathetic to, or were eventually convinced of the cause of CCP, including Feng Zikai and Zhang Leping.

6. “In the context of mainland China this bold self-determinative statement feels radical (at least to an outsider like myself).”

On the contrary, this sentence in itself is a very ordinary boastful statement which would not be seen by anyone in China as radical in the slightest.

7. comics as a career in China

Comic strips, editorial comics and story comics such as the traditional “lianhuanhua” have always existed in PRC. They are indeed not particularly innovative.

It was the introduction of manga and Taiwanese comics such as Cai Zhizhong’s work that inspired a new generation of cartoonists. In the late 1990s, a few magazines such as Beijing Cartoon were responsible for grooming them. Eventually most of these magazines were unable to sustain their running. The best of this generation, having endured the hardship and more or less matured, often publish their works through French publishers, and cooperate with French artists.

Nowadays, if someone want to choose comics as a career, outlets such as Zhiyin are still actively cultivating the domestic comic market with success. There has even been a webcomic portal, http://www.u17.com.

I’m not saying any of these artists are good, original or have anything worthwhile to say; but comics as a career path do exist in China.

8. American and French comics in China

Actually they were not entirely unheard of back in very early 1990s. For example, some people read Tintin, I read some Smurfs, my friend read Asterix and Obelix. And I seem to be one of the only people in China who got to own a copy of Captain Marvel back then.

That’s just the geek/pop culture front; on the mainstream/highbrow front, a considerable amount of foreign comic strips were translated and published in China.

However, it was mostly manga and anime that inspired people to draw their own comics, this was, and still is true.

9. “Japanese and dog Keep at a distance”

The cultural context is this:

There is a legend in China, that during the last days of Qing dynasty, when China was in the process of being colonized, some parks in foreign-occupied blocks of the cities have the sign “no entry for Chinese and dogs”.

I forget whether there’s any truth to this legend, but every Chinese know of it.

Just searched it. It’s a myth.

http://www.tianya.cn/publicforum/content/free/1/2130699.shtml

The actual English sign in this Shanghai park read:

“1. The Gardens are reserved for the Foreign Community.”

…

“4. Dogs and bicyles are not admitted.”

10. “downloaded copies of R. Crumb”

I’m not even sure anyone in China has developed a habit of reading American art comic at all, even now. There are superhero fans; some has read Watchmen before the showing of the movie; some titles such as Persepolis and Maus are translated and published legally. That’s about it. Did Chairman Ca explicitly say he read R. Crumb?

My final notes:

-I just realized the car in the article photo also has a Transformers sticker.

-The general, greater problem is the huge gap between… sorry, what outsiders think the Chinese think, and what the Chinese actually think. (I do not share the self-perception of most Chinese, but I’m weird.)

-From what I know, the Hong Kong fighting comic industry is a dreary place, where the comics are manufactured in a highly standardized process from which the assistants can’t learn anything, where any attempt at story sophiscation would be disrupted by the adamantine rule that each issue must contain fighting.

Hey thanks for the comments.

@Cuc, I understand some of your eyebrow raises, but maybe I should better explain some of these points because I feel like you are a little unfairly accusing me of sloppy writing. I think it is pretty clear from the context of this article that a lot of the observations are from my own subject position (hence using the I a lot more than I normally would) and when not, I included factual information that I could somewhat cite.

1) The term “Manhua” is not a term I’m callously throwing around. This is the term, for better or worse, that is being used by Chinese today for not only the historical but the contemporary. In Taiwan (where I was for a month) and Hong Kong (where I am now) they use that same word as well. The book I reference, Hong Kong Comics: The HIstory of Manhua, does a good job parsing out how the term loosened up to include Hong Kong productions. I didn’t mean the word choice as controversial, I meant it as conventional. Either way, I tried not to mince words up there and distinguish Mainland when I’m talking about it.

2) The Pop Culture attitudes towards Japanese: So I was in the Mainland for a couple of months (Shanghai, Xi’an, and Beijing) and met some of the most wonderful and nice people I’ve ever met. But I’m being honest here: there was still a HUGE resentment towards Japan among the older generation. This is putting it politely. Can you imagine seeing that sticker walking down the street as I did? (And I appreciate the context of in number 9 on that).

As Ca told me, and I tried to relay briefly, he was citing the same opening up in the 1990s that you are referencing. The way he put it was in 1994 all of a sudden there was a wealth of culture to sort through. He talked more about the impact of the Internet though than the TV (which leads to the first comic influence he listed being “R Crumb,” hence my line about the downloaded Crumb as influence).

3) Although Zikai studied in Japan, I still think his art did the things I said it did here. If anything it helps show how intertwined Manga/Manhua were at the start and 4) I’ll fix the typo and link switch-up

5) You are right that I oversimplified this. I just didn’t have the time or wealth of knowledge to put a whole history of Manhua up here, but didn’t want to exclude that time frame all together. But all I was trying to get at was that the only comics of that time were published through the government (or were pirated Tintin) and were published much less at that. I’m planning on expanding on this time frame on my personal blog in the future.

6) That was my reading of the statement as I pointed out. Not many other people I met would say “fuck,” but Cult Youth do! That’s just to say they feel counter-culture.

7) This point is fascinating and I’m glad you can illuminate because Ca couldn’t. I didn’t know there was a potential career, and he made it sound impossible which shocked me a bit.

8) Tintin was around as early as 70s and 80s in Mainland. Those were of course all pirated, so it still doesn’t change the fact you and your friends were technically breaking the law! Again, the point was Manga was the most widely available when 90s imports started.

10) I put it up in an early point, but yeah(!) he is a Crumb fan. If you look at his larger art pieces you can see the influence.

Okay. I did my part to best defend my information and thoughts, but as these things go I’m sure it wasn’t sufficient. I understand your frustration Cuc, and I’m sure I’d go to bat similarly if I saw someone else writing about Arab Comics in a pithy way. But I really tried not to be pithy! You are right that in the end that you inherently have more information than I do on the subject, and perhaps you could have written a similar piece better, but I felt the need to write it in the first place either way. I hope you can now better understand where I’m coming from and why I included the words/facts/opinions I did. The last thing I want is for a piece that I worked hard on to be considered sloppy or unfair.

@Domingos Is that really a myth? I’ve just seen it so frequently that I accept it is fact now. I guess all origin myths need a good story. For the record, if you go to the Shanghai Comics Museum they also cite Hokusai as the creator of “Manga.” Do you know where the term actually came from?

I’m no where near a close watcher of comics in China. I still have a lot to learn, and you’ve already taught me a few things. :-)

>attitudes towards Japan

A Chinese is capable of enjoying the cultural products of Japan and believing Japanese as a race is rotten at the same time, without ever feeling any moral inconsistency.

>Feng Zikai

I’d phrase it as “Feng Zikai, with his works, imported the word ‘manhua’ into the Chinese vocabulary”.

>R. Crumb and Cult Youth

I see, so that is what he upholds as his ideas.

Santo Kyoden used the compound in 1798. Hanabusa Itcho used “mankaku” in the 17th century.

Pingback: Comics Abroad | POSTWALLA

Pingback: Comics Abroad | POSTWALLA

Hi, I am a french comicbook artist living in Shanghai. I write articles about comics in China. The article I am working on is about Feng Zikai (I’ve interviewed his family, about Feng Zikai museum in Shanghai). I would like to have the contact of the people of CULT, planning to go to Beijing soon.

Pingback: Mini-documentary on Cult Youth on making comix in China | ??? :: 88 Bar