In terms of mainstream culture, Chester Brown’s Paying for It—a diaristic account of his experiences of paying for sex between 1999-2002—has been the most discussed comic of the year. And apart from Robert Crumb’s Genesis, probably the most widely exposed of the past half-decade or so. This is not surprising, since it addresses polemically a difficult and largely unacknowledged but perennially challenging issue: prostitution and the underlying question of how sexuality straddles identity and commodity.

In an pre-publication comment on this site, Noah took issue with an early review by Tom Spurgeon, which he saw as unwilling to engage with the socio-political issues addressed in the book—something he took as emblematic of how comics critics tend to prioritize form over content, simply put. Never mind that his examples of such priorities in comics criticism were highly tendentious, he has a point that there is a holdover from traditional comics appreciation that privileges form, even if contemporary criticism increasingly transcends it.

In an pre-publication comment on this site, Noah took issue with an early review by Tom Spurgeon, which he saw as unwilling to engage with the socio-political issues addressed in the book—something he took as emblematic of how comics critics tend to prioritize form over content, simply put. Never mind that his examples of such priorities in comics criticism were highly tendentious, he has a point that there is a holdover from traditional comics appreciation that privileges form, even if contemporary criticism increasingly transcends it.

As it has turned out, however, the reception of Paying for It has generally engaged Brown’s polemics head-on, to the extent—ironically—that the form in which they are presented has been largely ignored. Noah himself has done better than most on this issue. In his review, for example, he makes the important observation that Brown’s dispassionate presentation and robotic self-portrayal can be seen to reflect and inform his ideology and political message.

Beyond that, however, he reveals a lack of sensitivity to Brown’s artistic achievement. In a subsequent comment, he writes about the book: “formally it doesn’t really do very much…but I guess that’s autobio comics for you….”

Not only does this go a long way toward explaining why Noah failed to appreciate what Spurgeon was trying to do in his review, it seems to me emblematic of intellectual comics criticism as it is practiced today—a tendency to regard form as a transparent vessel for conceptual issues. To be sure, there is plenty of those to discuss in Paying for It, but I am confident that the reason it provokes interest beyond its superficial provocation, and the reason that I suspect it will retain interest once the discourse it addresses has moved on, is precisely Brown’s personal story and the way he has given it form.

Not only does this go a long way toward explaining why Noah failed to appreciate what Spurgeon was trying to do in his review, it seems to me emblematic of intellectual comics criticism as it is practiced today—a tendency to regard form as a transparent vessel for conceptual issues. To be sure, there is plenty of those to discuss in Paying for It, but I am confident that the reason it provokes interest beyond its superficial provocation, and the reason that I suspect it will retain interest once the discourse it addresses has moved on, is precisely Brown’s personal story and the way he has given it form.

As a polemic, the book is forceful and compelling, but it founds its basically well-reasoned political stance on an idiosyncratic, ineptly argued rationale. Brown’s position that prostitution should be decriminalized but not regulated, though founded in libertarian ideology, is pragmatically rational. Much of the rest of his discourse, however, is less so: not only does the basic premise, that romantically founded relationships are (probably) inherently wrong, seem more of a personal exorcism than a universal truth, but more specific arguments also grate against lived experience. Readers with any knowledge of substance abuse, for example, may find themselves mystified by Brown’s assertion that dependency boils down to rational choice and has no physical symptoms (appendix 17).

Worse is the naivité he brings to his discussion of such phenomena as pimping and sex trafficking. He assumes that coercion only really concerns illegal immigrants and that any other prostitute subjected to abuse can go to the police anytime and is thus—like the drug addict—in her situation by choice (appendices 12-13). Similarly, his discussions in the notes of whether certain prostitutes he saw were “sex slaves” seems disingenuous, if not outright self-serving, not the least when considered against the admirable honesty with which he describes in the main part of the book the signs of coercion picked up during his encounters (pp. 91-92, 186-88, 207-8, and the accompanying notes).

Worse is the naivité he brings to his discussion of such phenomena as pimping and sex trafficking. He assumes that coercion only really concerns illegal immigrants and that any other prostitute subjected to abuse can go to the police anytime and is thus—like the drug addict—in her situation by choice (appendices 12-13). Similarly, his discussions in the notes of whether certain prostitutes he saw were “sex slaves” seems disingenuous, if not outright self-serving, not the least when considered against the admirable honesty with which he describes in the main part of the book the signs of coercion picked up during his encounters (pp. 91-92, 186-88, 207-8, and the accompanying notes).

Dubious in relation to any human relation, the libertarian notion of humans as autonomous engines of dispassionate choice and our bodies as property rather than incarnation (appendix 4) is downright absurd when applied to something as emotionally fraught and psychologically complex as sexuality and its commodification in society. Brown seems to believe that hard currency is some kind of elixir for human relations. Although he clearly does not even contemplate fatherhood, he for instance expects us to accept that his utopia of commodified sex and contractual child-rearing (appendices 3, 18) would somehow make for a healthier, more nurturing environment for children to grow up in.

Here lies both the strength and weakness of the book. As political discourse it is at best engaged and thought-provoking, but ultimately simplistic—too reliant on the universal application of personal experience, with a slapdash reading list standing in for actual research. As a memoir, however, it is a deeply involved, stirring examination of how sexuality pervades social action and confounds politics. As several reviewers have noted, one of the book’s main virtues is that it is written by a john who is out, and that it succeeds in humanizing not only that stigmatized demographic, but also sex workers and sex work itself. This in itself is a major achievement.

Here lies both the strength and weakness of the book. As political discourse it is at best engaged and thought-provoking, but ultimately simplistic—too reliant on the universal application of personal experience, with a slapdash reading list standing in for actual research. As a memoir, however, it is a deeply involved, stirring examination of how sexuality pervades social action and confounds politics. As several reviewers have noted, one of the book’s main virtues is that it is written by a john who is out, and that it succeeds in humanizing not only that stigmatized demographic, but also sex workers and sex work itself. This in itself is a major achievement.

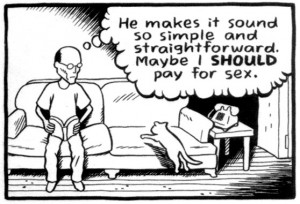

I would thus agree with Spurgeon’s argument that Paying for It, the comics memoir, is richer and more satisfying than the preachy appendix. The concomitant conclusion, that Brown would have done well to leave out the latter, however, is less convincing. The narrative gains in power as a tangled, resonant substructure for the polemic, and the political argument is both bolstered and countered by the lived experience girding it. Where in the appendix Brown is happy to make dogmatic and at times fairly extreme statements, in the comics he allows space for counterarguments, voiced by his friends as well as a couple of prostitutes, one of which—as Noah and others have pointed out—challenges outright his philosophy as lazy, arguing that the kind of hard work that goes into a romantic relationship is required for anything of value in this world.

And his description of his own evolution from tentative and sensitive client to experienced, at times rather cynical, customer is revealing not just of his personality, but of how paid sex may affect your appraisal of partners. Even more compromising—personally as well as rhetorically—are such sequences as the one where he describes himself getting off on a prostitute’s exclamations of pain.

And his description of his own evolution from tentative and sensitive client to experienced, at times rather cynical, customer is revealing not just of his personality, but of how paid sex may affect your appraisal of partners. Even more compromising—personally as well as rhetorically—are such sequences as the one where he describes himself getting off on a prostitute’s exclamations of pain.

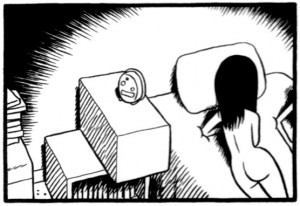

And his strategy of obscuring the faces and changing any distinctive features or characteristics of the prostitutes, avowedly done in order to protect their privacy, not only makes manifest on the page the objectification inherent in the book’s subject and ideology, but reveals Brown’s commitment to authenticity. Instead of turning them unrecognizable by changing their appearance, he makes them anonymous. In contrast to colleagues such as Steve Ditko and Dave Sim (though less so with him than one might think), Brown’s instincts as an artist are simply too sound for him to let his work conform narrowly to ideology, no matter how strongly he feels about it.

One of his more puzzling statements in the appendix is his view of sex as a ‘sacred activity.’ This cannot be reduced to his libertarian beliefs in individual freedom. Readers familiar with his previous book, Louis Riel (2003), will remember its conflicted protagonist, believing himself to be acting according to divine ordinance and finding that other designs may be confounding his freedom of action. The possibility of free agency is a central concern.

One of his more puzzling statements in the appendix is his view of sex as a ‘sacred activity.’ This cannot be reduced to his libertarian beliefs in individual freedom. Readers familiar with his previous book, Louis Riel (2003), will remember its conflicted protagonist, believing himself to be acting according to divine ordinance and finding that other designs may be confounding his freedom of action. The possibility of free agency is a central concern.

Though it is less overtly spiritually charged, this problem remains somewhere at the core of Paying for It, which sees Brown more pointedly championing his choices in the face of social norms. And although he no longer confesses as a Christian, and has orchestrated his most spartan mise-en-scène yet—a far cry from the vintage texturing of Riel—his images are still imbued with a compelling sense of meaning. One gets the sense that the detachment with which he describes his experience is the same as the one with which he examined the life of Riel.

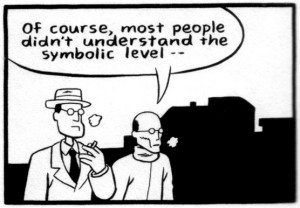

As in that book, many scenes are viewed from above, from a kind of “God’s eye-perspective.” The peepshow aesthetic of the tiny two-by-three paneling seems to be for the benefit of an omniscient viewer, who at times loses interest and lets the eye wander, decentering the compositions. Chester walks, talks, and fucks under the scrutiny of a dispassionate oculus, darkening around the edges. It is almost as if he is inviting a higher judgment to balance out his own.

As in that book, many scenes are viewed from above, from a kind of “God’s eye-perspective.” The peepshow aesthetic of the tiny two-by-three paneling seems to be for the benefit of an omniscient viewer, who at times loses interest and lets the eye wander, decentering the compositions. Chester walks, talks, and fucks under the scrutiny of a dispassionate oculus, darkening around the edges. It is almost as if he is inviting a higher judgment to balance out his own.

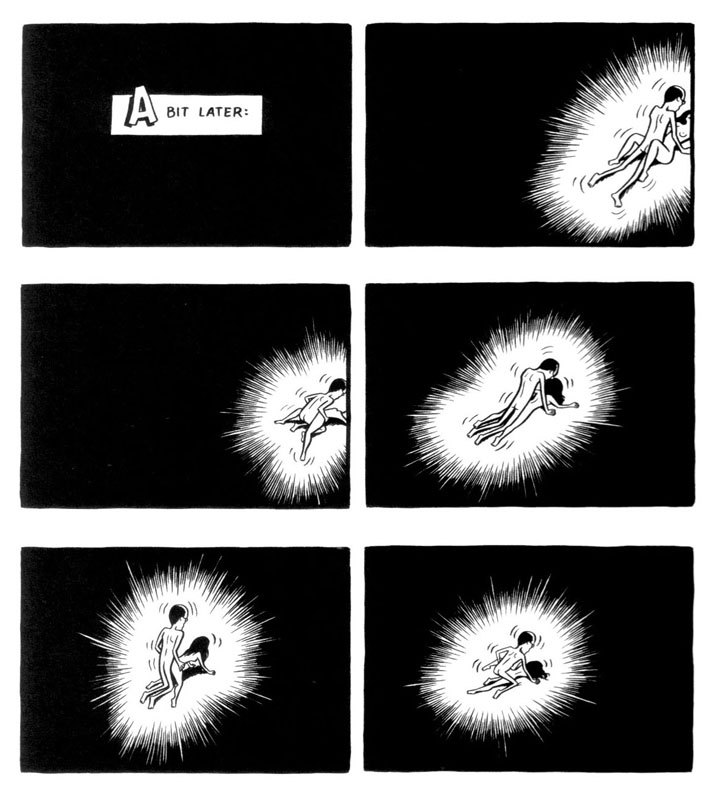

Sex scenes are privileged by even greater distance. They are uniformly denoted by a throbbing glow in the dark, blocking out the surroundings (this is worked to hilarious effect in chapter 2—the sequence where Chester keeps stopping, with the banal details of the surrounding room appearing each time). A necessary way of avoiding the interference that overly graphic renditions would create, this approach lends universalism to these scenes, threading them through the narrative as its central, ‘sacred’ constituent.

Brown’s cartooning has struck me as invoking this kind of higher order since at least, and unsurprisingly, his 1990s Gospel adaptations, which routinely employed a similarly elevated perspective, pared-down panel compositions, and suggestive framing to great effect. The explosion of the grid in I Never Liked You (collected 1994) and the claustrophobic, petri-dish effect of the gridding in Underwater (1994-97), each in their way seemed to solicit scrutiny from above. In Paying for It, Brown works to great effect the inevitable, often ominous, signification of gestures—frequently singled out in individual panels; the incursion of random passersby in streets backed by theatrically silhouetted buildings; and the suspension of time and motion as Chester and his friends Seth and Joe Matt stride down the street, their talk at an end.

The point is that Brown, contrary to Noah’s dismissal, always achieves a lot with his images and panel-to-panel storytelling. His power to imbue any scene with an ineffable sense of meaning is one of his great gifts as a cartoonist, a gift few critics have attempted to critique or explicate, and which Spurgeon addressed sensitively in his review.

Paying for It is a brave book, groundbreaking in its premise alone, but beyond its polemic it is an unflinching self-portrait, synthesizing its author’s ideology, sexuality, pathology, and spirituality on the page.

Great post Matthias! I especially liked the part in which you state that some artists are too talented for their own good. I admired Chester Brown greatly during his _Yummy Fur_ and _Underwater_ years. After that, not so much… I regret it because, beyond a certain amount of talent, comics artists tend to migrate to greener pastures. Chester did not…

I still haven’t read _Paying For It_ though…

I like this post too; mulling a response maybe later today….

And, as promised, my response is here.

Domingos, thanks! I don’t think Brown has gone astray though. I would easily rank Riel amongst his best work and obviously like Paying for It a lot too. What would you rather have seen him do?

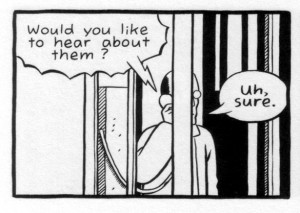

Noah, I don’t want to take your experience of the drawings away from you, but you seem willfully oblivious to how unusual they are. Who else does anything remotely resembling what he does? How can you say a page like this is banal? In what way? It’s beautifully punctuated page, given a symbolic sense of restricted agency, even menace, by the bars of the phone booth and the distracted, yet lingering point of view. It’s almost like a Godard shot.

You’re right that he’s going for a flat, distanced feel, but as you yourself have demonstrated that only makes the work resonate on a more complex level. If he’d done something only a slightly bit more adorned or sensual, he would have risked charges of self-indulgence and completely undermined his political and personal argument. And would it really have been a better book if it merely stuck all the way to its rather myopic polemic? It’s *interesting that he in some ways undermines it, isn’t it?

As for the spiritual charge, I think it’s completely fair to disagree, and in any case it’s something that feels more readily present if one is familiar with Brown’s previous work.

Replacing it with “the eye of porn”, however, is just ludicrous. I haven’t read Linda Williams, but come on, since when was getting off not part of porn? And in your explication in the comments of the other thread, you seem to disassociate the sex scenes entirely from all the other stuff that’s going on the the book. To me Chester debating these problems with his friends, thinking about his life without girlfriends, and pillowtalking with the girls he sees is so much more than bumping and grinding. It’s a really rich, searching book, full of conflicting ideas and constant questioning.

Porn is a genre with various tropes, just like any other genre. Brown uses many of the tropes in his depiction of sex. He represents it sadistically — that is, as repetitive and distanced in the service of control. Turning sex into a regimented series of acts performed by consumable bodies; I don’t know. It doesn’t seem like a particularly large leap to me from that to porn. The book as a whole is like that too, even in its depictions of the bits that aren’t sex. And I think he deliberately makes the consumable sex a metaphor for life.

It would have been a much better book not if it were more sensual, but if he had figured out a way not to dehumanize the women he slept with, and, for that matter, himself. His excuses in that regard sound like excuses. If he couldn’t find a way to treat the women he is supposedly championing as individual human beings in an autobiographical account, then he should have either reconsidered the genre or jettisoned the project. I think it’s really a disastrous flaw.

I could certainly dislike the art more. The page you show there is certainly more interesting than the sex scenes. But in general it seems stiff, unexpressive, and restrained to the point of timidity. I feel like there’s this premium in some contemporary autobio comics on being very, very dry, as if any sign of flamboyance will undercut the verisimilitude. I just find is depressing.

I think you’re making way too much of the coldness of the art. As I’ve said, I agree that it’s there, but there’s plenty of human inquiry in the book too. You seem to ignore that. As for the control you’re talking about, it seems off the mark to me. Yes, Brown has an issue with control, but it has less to do with other people than with himself and society. I have a very hard time buying your sadist argument.

Humanizing the prostitutes, or detailing his relationship with ‘Denise’, as some reviewers seem to have wanted, would have made for a radically different book. This might have been a good book, but to me, as I said, the anonymity is plenty interesting on its own, creating a fascinating frisson between the polemic and the narrative. Also, personalizing the book too much would have risked undermining the universal tone Brown seems to be going for, as well as his argument more generally.

Anyway, your criteria and mine for judging the book’s success appear quite different. Please correct me if I’m wrong, but it seems you would have preferred a book that stated its socio-political argument more clearly and convincingly and didn’t hit any false notes, where for me those false notes are where the life and the art is.

What autobiographical comics are you talking about? There is plenty of visually inventive or graphically strong autobiography, from Carol Tyler and Lynda Barry to David B. and Fabrice Neaud to Debbie Drechsler and Phoebe Gloeckner. I guess you’re perhaps talking about Joe Matt (where I would agree), Alison Bechdel (ditto), or perhaps Ariel Shrag (also), but to lump Brown in with them to me is just patently insensitive. His images are so much richer than theirs. There is so much invention, just in those few examples I’ve shown. Spurgeon’s line about ‘Brown illustrating the phone book’ is right on.

I think Ariel Schrag is a much more interesting artist visually than Brown. People like Joe Matt and Bechdel fit though.

“Also, personalizing the book too much would have risked undermining the universal tone Brown seems to be going for.”

I don’t think sterile distanced objectivity is universal. I think it is often presented as universal. On the contrary, I believe that presenting women as if they are human beings with faces is a lot more universal than chopping off their heads.

“Please correct me if I’m wrong, but it seems you would have preferred a book that stated its socio-political argument more clearly and convincingly and didn’t hit any false notes, where for me those false notes are where the life and the art is.”

Nope. I think that it’s clear from my claim that Schrag is a more interesting artist that perfection, formal or otherwise, is not what I want. I’d like a book that visually is less like eating my way through a dry bowl of bran flakes, and that isn’t ideologically committed to a world where men are cadavers and women are robbed of their facial features in the name of a dubious and thoroughly compromised gallantry.

“I believe that presenting women as if they are human beings with faces is a lot more universal than chopping off their heads.”

Agreed, but…what about Chris Ware, and his systematic refusal to show the faces of the women who interact with Jimmy Corrigan?

I think you could argue that Ware has some problems with female characters. He seems to be aware of it and to try to overcome it in various ways. Certainly, he has female characters who have faces, and are even the main characters in his narratives.

Brown’s problem is not just with women in general (he does show his girlfriend’s face) but rather that he’s specifically claiming to be humanizing/sympathizing with prostitutes. Turning them into anonymous ciphers, therefore, is a real problem for his stated aesthetic goals.

Yes, but is it a problem for the book as a work of art? I really don’t think so.

Well, maybe we just have to agree to disagree then. I think there’s really enough dehumanizing of prostitutes in the world that I don’t find an artist doing it to be either insightful or moving. The fact that he claims to want to be doing the exact opposite makes it difficult for me to see it as anything other than an artistic failure.

Sure, different strokes and all that, but I also think you’re overemphasizing the dehumanization of these women.

The *depersonalization is noticeable for sure, because of the obscured faces, but as a reader I definitely came away with what I felt was a much more nuanced and *human* impression of the profession. As I wrote, I think it works on a more subtle level, as a manifestation of the commodification inherent in both sex work and libertarianism.

In general, Brown’s whole description of logistics and incidental detail creates a rich, lived context for his argument. There’s distance, but also a lot of life in that book.

“Porn is a genre with various tropes, just like any other genre. Brown uses many of the tropes in his depiction of sex. He represents it sadistically — that is, as repetitive and distanced in the service of control.”

Yes, Brown uses many of the tropes of porn…but if he uses some, not all…If it’s in the service not of getting off, but of something else, then it’s not porn, but something else (commenting on porn’s tropes, perhaps? Exploring what makes porn what it is, without quite delivering it, etc.)

As I said, I haven’t read the book…but none of the page scans I’ve seen here seem to suggest the book is pornography. The book may be bad…or have problematic or indefensible politics…It may dehumanize women in ways that porn also does…and so there may be links between the two things….but to claim that the book uses the “eye of porn” or even that the sex scenes are “pornographic” is fairly misleading and weakens whatever the rest of the argument is.

“I definitely came away with what I felt was a much more nuanced and *human* impression of the profession. ”

That depresses me, honestly. You don’t need to read very much about sex workers to get a more nuanced and human impression of the profession than Brown shows, I don’t think….

Maybe so, but I hadn’t. Doesn’t matter. The point is I think you’re making too much of this whole dehumanization thing.

———————–

Noah Berlatsky says:

Porn is a genre with various tropes, just like any other genre. Brown uses many of the tropes in his depiction of sex…

————————

There’s been much discussion of how he visually dehumanizes the faces of the women he pays for sex with, but I haven’t seen any note of how (in all the images posted online so far, at least) he de-individualizes their bodies as well; all one identically luscious, pin-up, slim-but-curvy sex-object type.

(Why, to pick on a favorite theme at HU, that’s no different than the de-individualization of rendering all blacks as lookalike blubber-lipped “coons”…)

————————-

Matthias Wivel says:

…I also think [Noah is] overemphasizing the dehumanization of these women.

————————–

True, it’s not a complete dehumanization. Yet, consider that any verbal interactions between Brown and the women he’s financially involved with are taking place in an “employer to employee” power relationship. Does anyone think these women feel free to express anything remotely close to the full range of who they and what they think about their “job” to the “Johns”?

Especially when now the customers have the power to, as Brown frequently does, post a rating of their “job performance” online.

But then, to at least Brown’s version of Libertarianism, all humans are units of economic exchange; basically interchangeable as Phillips-head screwdrivers from different manufacturers.

There’s a term for failing to see the range of humanity of people one deals with on a limited basis, such as toll-booth clerks and supermarket cashiers: “thinging.”

And that Brown sees sex as spiritual, and something to be traded for money as well, is more than a little mind-boggling. What’s his idea of prayer, then?

(…Though I just remembered how to the ancient Romans religious ritual was like a contract: “I will sacrifice a bull to you, Apollo, and in return you will grant me success with…”)

Well, I agree, and that’s why I think the depersonalization in the way they’re represented is thematically appropriate, even if it subverts Brown’s political argument.

In 1995 I wrote an essay about Chester Brown’s work and I reached the conclusion that this http://tinyurl.com/6dpoxdo drawing explains a lot. It shows that Joe Sacco didn’t invent the eyeglasses without eyes device (they both use it for very different reasons, by the way). It also shows a very detached child…

I didn’t answer your question Matthias: I don’t dislike _Louis Riel_ or anything, but I would love to see _Underwater_ finished.

Yeah, that was a fantastically promising comic. He doesn’t seem to think it’s possible though.

Blank glasses surely go back much further than that. What was your conclusion about the cover?

In case anyone is interested, I came across a discussion of Paying for It in the introduction to an anti-prostitution group’s new study about the rottenness of johns:

http://www.prostitutionresearch.com/pdfs/Farleyetal2011ComparingSexBuyers.pdf

I guess it goes to show that Brown was honest enough to include many details that hurt his overall case. Also notable is the study’s approving reference to Brown’s adolescent shame over his Playboy obsession.

Pingback: Thoughts on Paying For It, and Chester Brown’s Polemic « Manga Widget