The following lists were submitted in response to the question, “What are the ten comics works you consider your favorites, the best, or the most significant?” All lists have been edited for consistency, clarity, and to fix minor copy errors. Unranked lists are alphabetized by title. In instances where the vote varies somewhat with the Top 115 entry the vote was counted towards, an explanation of how the vote was counted appears below it.

In the case of divided votes, only works fitting the description that received multiple votes on their own received the benefit. For example, in Jessica Abel’s list, she voted for The Post-Superhero comics of David Mazzucchelli. That vote was divided evenly between Asterios Polyp and Paul Auster’s City of Glass because they fit that description and received multiple votes on their own. It was not in any way applied to the The Rubber Blanket Stories because that material did not receive multiple votes from other participants.

Flint Hasbudak

Cartoonist, Totuk

Ken Parker, Giancarlo Berardi & Ivo Milazzo

- Akira, Katsuhiro Otomo

- Batman, Bob Kane & Bill Finger, with Jerry Robinson

- Brooklyn Dreams, J. M. DeMatteis & Glenn Barr

- Corto Maltese, Hugo Pratt

- The Creech, Greg Capullo

- Ken Parker, Giancarlo Berardi & Ivo Milazzo

COMMENTS

Tough question! But to put a few in mind, I’ve always admired these.

A list can be very long. And obviously there are many I haven’t read yet.

______________________________________________

Greg Hatcher

Contributing Writer, Comic Book Resources

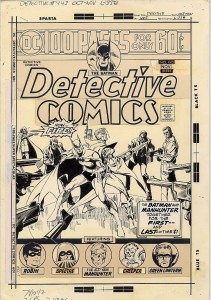

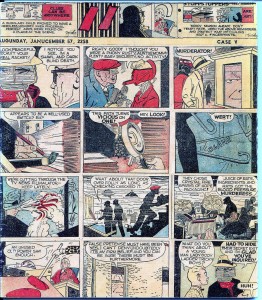

Detective Comics, Archie Goodwin, et al.

- The Batman Stories, Denny O’Neil & Neal Adams

- Calvin and Hobbes, Bill Watterson

- Daredevil: Born Again, Frank Miller & David Mazzucchelli

- The Defenders Stories, Steve Gerber & Sal Buscema, with Vince Colletta, et al.

- The Fantastic Four, Stan Lee & Jack Kirby, with Joe Sinnott, et al.

- Fax from Sarajevo, Joe Kubert

- From Hell, Alan Moore & Eddie Campbell

- Manhunter, Archie Goodwin & Walter Simonson, and The Batman Stories in Detective Comics #437-443, Archie Goodwin, Steve Englehart, et al.

- The Marvelman [Miracleman] Stories, Alan Moore & Garry Leach, Alan Davis, John Totleben, et al.

- Smile, Raina Telgemaier

COMMENTS

The best comics run of all time? If you mean just character and story, I’d go with the Archie Goodwin-Walt Simonson Manhunter. That was just brilliant. Modern creators are still going back to the stuff, there—ninjas, clones, superheroic anti-heroes that are willing to use lethal force. Not to mention an approach to the art itself that was 20 years ahead of its time. Look at the original Manhunter today, and Simonson’s layout and lettering doesn’t look dated at all.

But really, I’d take it a step further. I’d add that the comics in which those seven Manhunter installments appeared, Detective Comics #437-443, were themselves great comics. Goodwin was writing the Batman lead feature as well, and he kept luring guys like Alex Toth and a young Howard Chaykin to illustrate them, along with stalwarts like Jim Aparo and Dick Giordano. It’s also where you found the original “Night of the Stalker” by Steve Englehart, one of the greatest Batman short stories ever.

[On The Defenders Stories] Social commentary and satire masquerading as Marvel soap opera and amazingly successful today.

[On The Marvelman [Miracleman] Stories] I think Miracleman is a better superhero deconstruction than Watchmen, which (heresy!) hasn’t aged well, and also I’ve gotten so sick of superhero writers cribbing from it that Watchmen is tainted for me. But this is mostly because if you have to choose between Watchmen and Miracleman, Miracleman is better.

[On Smile] This is kind of an upstart entry, but the craft involved just knocks me out, and the entire project serves as a primer of the kind of thing mainstream comics ought to be doing and just…don’t do.

______________________________________________

Charles Hatfield

Associate Professor of English, University of California at Northridge; author, Alternative Comics: An Emerging Literature; contributing writer, The Panelists, The Comics Journal

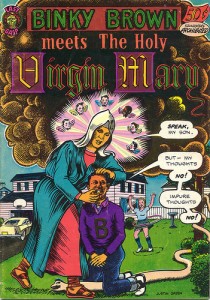

Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary, Justin Green

- L’Ascension du haut-mal [Epileptic], David B.

- Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary, Justin Green

- The Book of Jim, Jim Woodring

- “Flies on the Ceiling,” Jaime Hernandez

Counted as a vote for The Locas Stories, Jaime Hernandez - Graffiti Kitchen, Eddie Campbell

Counted as a vote for The Alec Stories, including The Fate of the Artist, Eddie Campbell - “The Hannah Story,” Carol Tyler

- Human Diastrophism [Blood of Palomar], Gilbert Hernandez

Counted as a vote for The Palomar Stories, Gilbert Hernandez - Peanuts, Charles M. Schulz (especially circa 1955-1965)

- “Spawn,”, “The Glory Boat!”, “The Pact!”, and “The Death Wish of Terrible Turpin!”, Jack Kirby, with Mike Royer

Counted as a vote for The Fourth World Stories, Jack Kirby, with Mike Royer, et al. - Thimble Theatre, starring Popeye, E. C. Segar

______________________________________________

David Heatley

Cartoonist, Deadpan, My Brain Is Hanging Upside Down; contributing artist, The New Yorker, The New York Times

“The Hannah Story,” Carol Tyler

- 1. “The Hannah Story,” Carol Tyler

- 2. Maus: A Survivor’s Tale, Art Spiegelman

- 3. Fun Home, Alison Bechdel

- 4. Quimby the Mouse, Chris Ware

- 5. Twentieth-Century Eightball, Daniel Clowes

- 6. Black Hole, Charles Burns

- 7. Collected Works, Volumes 1-5, Shigeru Seguira

- 8. My Trouble with Women, R. Crumb

Counted as a vote for The Weirdo-Era Stories, R. Crumb - 9. Jimbo in Paradise, Gary Panter

- 10. I Never Liked You, Chester Brown

COMMENTS

I hate having to actually rank these because this kind of thing changes all the time in my head. Here’s a stab at it though.

Runners-up: Peanuts (1950s era), Charles M. Schulz; Perfect Example, John Porcellino; The ACME Novelty Library, Chris Ware; Affiches—film posters by Albert Dubout; Wilson, Daniel Clowes; My New York Diary, Julie Doucet; Norakuro, Suiho Tagawa; Dirtbag (mini zines), Dave Kiersh; Annual Illustrated Calendars, Leif Goldberg; Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary, Justin Green; It’s a Good Life, If You Don’t Weaken, Seth; “Bomb Scare”, Adrian Tomine; Schizo, Ivan Brunetti; Nowhere, Debbie Drechsler

______________________________________________

Jeet Heer

Co-editor, A Comics Studies Reader, Arguing Comics: Literary Masters on a Popular Medium; contributing writer, Comics Comics, The Comics Journal

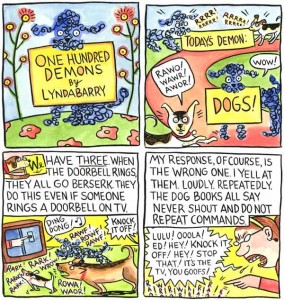

ONE! HUNDRED! DEMONS!, Lynda Barry

- 1. Krazy Kat, George Herriman

- 2. Peanuts, Charles M. Schulz

- 3. Maus: A Survivor’s Tale, Art Spiegelman

- 4. Bob ‘n’ Harv’s Comics, Harvey Pekar & R. Crumb

Counted as a vote for American Splendor, Harvey Pekar, with R. Crumb, et al. - 5. Jimmy Corrigan: The Smartest Kid on Earth, Chris Ware

- 6. ONE! HUNDRED! DEMONS!, Lynda Barry

- 7. The Locas Stories, Jaime Hernandez

- 8. The Palomar Stories, Gilbert Hernandez

- 9. I Never Liked You, Chester Brown

- 10. My New York Diary, Julie Doucet

______________________________________________

Danny Hellman

Contributing illustrator, The Village Voice, Guitar World

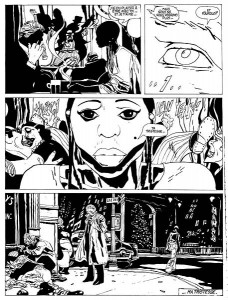

Alack Sinner, José Muñoz & Carlos Sampayo

- Alack Sinner, José Muñoz & Carlos Sampayo

- Captain Marvel, C. C. Beck & Otto Binder, et al.

- Chandler: Red Tide, Jim Steranko

- A Contract with God and Other Tenement Stories, Will Eisner

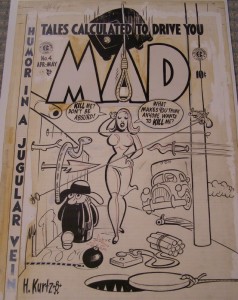

- The EC Comics Stories, Wallace Wood, et al.

Counted as a 0.33 vote each for The EC Comics Science-Fiction Stories, Al Feldstein & Wallace Wood, Al Williamson, Joe Orlando, et al., The EC Comics War Stories, Harvey Kurtzman & Jack Davis, John Severin, Wallace Wood, et al., and MAD #1-28, Harvey Kurtzman & Will Elder, Wallace Wood, Jack Davis, et al. - The Fantastic Four, Stan Lee & Jack Kirby, with Joe Sinnott, et al.

- Le Garage hermétique [The Airtight Garage], Jean “Moebius” Giraud

- Little Nemo in Slumberland, Winsor McCay

- The MAD Stories, Mort Drucker

- The Zap Comix stories, R. Crumb

Counted as a vote for The Counterculture-Era Stories, R. Crumb

COMMENTS

This list is all about the art; screw the writers. [Note: Danny Hellman only included the names of the cartoonists/pencilers in his lists above and below. The editor added the names of separate scriptwriters and inkers. This was done for the sake of completeness and editorial consistency.]

And some highly honorable mentions: Abandoned Cars, Tim Lane; The Arcade Stories, Spain Rodriguez; Batman: The Killing Joke, Alan Moore & Brian Bolland; The Captain Marvel, Jr. Stories, Mac Raboy, et al.; Cheech Wizard, Vaughn Bodé; Cochlea and Eustachia, Hans Rickheit; Coochy Cooty, Robert Williams; Ed the Happy Clown, Chester Brown; El Borbah, Charles Burns; The Howard the Duck Stories, Steve Gerber & Gene Colan, with Steve Leialoha, et al.; Idyl, Jeffrey Catherine Jones; The Incal, Alexandro Jodorowsky & Jean “Moebius” Giraud; Maakies, Tony Millionaire; The MAD Stories, Bob Clarke; The MAD Stories, Paul Coker, Jr.; The MAD Stories, Harvey Kurtzman & Will Elder; The Metamorpho Stories, Bob Haney & Ramona Fradon; The Nick Fury, Agent of S.H.I.E.L.D. Stories, Jim Steranko; The Spirit, Will Eisner; Snappy Sammy Snoot, Skip Williamson; Trashman, Spain Rodriguez; Trots and Bonnie, Shary Flenniken

______________________________________________

Sam Henderson

Cartoonist, Magic Whistle

MAD, Harvey Kurtzman, et al.

- Books, B. Kliban

- The Complete Crumb Comics, R. Crumb

Counted a 0.5 vote each for The Counterculture-Era Stories, R. Crumb, and The Weirdo-Era Stories, R. Crumb - The Dell Comics Stories, John Stanley, et al.

Counted as a vote for The Little Lulu Stories, John Stanley, with Irving Tripp - The Fourth World Stories, Jack Kirby, with Mike Royer, et al.

- Krazy Kat, George Herriman

- MAD #1-28, Harvey Kurtzman & Will Elder, Wallace Wood, Jack Davis, et al.

- Nancy, Ernie Bushmiller

- Peanuts, Charles M. Schulz

- Pogo, Walt Kelly

- Thimble Theatre, starring Popeye, E. C. Segar

______________________________________________

Alex Hoffman

Cartoonist, Libertarian Rabbits from Outer Space; Editorial cartoonist, When Falls the Coliseum

Life in Hell, Matt Groening

- Angora Napkin, Troy Little

- The Book of Grickle, Graham Annable

- Calvin and Hobbes, Bill Watterson

- The Editorial Cartoons, Eric Allie

- The Editorial Cartoons, David Horsey

- The Editorial Cartoons, Michael Ramirez

- Everybody Is Stupid Except for Me and Other Astute Observations, Peter Bagge

- Life in Hell, Matt Groening

- Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal, Zach Weiner

- Watchmen, Alan Moore & Dave Gibbons

______________________________________________

Ben Horak

Cartoonist, Grump Toast

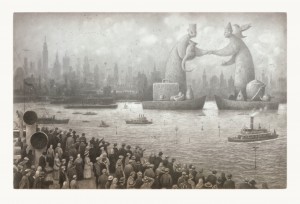

The Arrival, Shaun Tan

- The Arrival, Shaun Tan

- Berlin, Jason Lutes

- The Blot, Tom Neely

- Brat Pack, Rick Veitch

- Ed the Happy Clown, Chester Brown

- The Frank Stories, Jim Woodring

- The Left Bank Gang, Jason

- Panorama of Hell, Hideshi Hino

- Percy Gloom, Cathy Malkasian

- Six Hundred Seventy-Six Apparitions of Killoffer, Patrice Killoffer

______________________________________________

Kenneth Huey

Contributing cartoonist, Commies from Mars; Illustrator; “Humanoid,” Church of the Subgenius

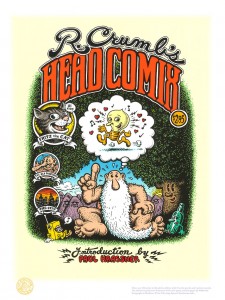

Head Comix, R. Crumb

- The Conan the Barbarian Stories, Roy Thomas & Barry Windsor-Smith, with Sal Buscema, et al.

- Le Garage hermétique [The Airtight Garage], Jean “Moebius” Giraud

- Head Comix, R. Crumb

Counted as a vote for The Counterculture-Era Stories, R. Crumb - Little Nemo in Slumberland, Winsor McCay

- The Nick Fury, Agent of S.H.I.E.L.D Stories, Jim Steranko, with Joe Sinnott, et al.

- Pogo, Walt Kelly

- The Sandman, Jack Kirby & Joe Simon, with Michael Fleisher, et al.

- Tarzan of the Apes (graphic novel), Burne Hogarth

- Torpedo 1936, Enrique Sánchez Abulí & Jordi Bernet

- The X-Men Stories, Roy Thomas & Neal Adams, with Tom Palmer, et al.

COMMENTS

Any “best of” list naturally invites a vigorous “sez who?” After all, who among us is truly qualified to judge the comparative importance of, say Lyonel Feininger’s The Kin-der-Kids vs. John Byrne’s run on The Fantastic Four? So, I’ll do something a bit more modest. Off the top of my head, these are ten features that have meant a lot to me over the years.

______________________________________________

Jelle Hugaerts

Contributing writer, Forbidden Planet International

Conte démoniaque, Aristophane

- Bar Miki, Michelangelo Setola

- Conte démoniaque [Demonic Tale], Aristophane

- Cowboy Henk, Kamagurka & Herr Seele

- Eläkeläinen muistelee [Memoirs of a Pensioner], Kalervo Palsa

- “Gynecology,” Daniel Clowes

Counted as a vote for Caricature: Nine Stories, Daniel Clowes - I Never Liked You, Chester Brown

- Jimmy Corrigan: The Smartest Kid on Earth, Chris Ware

- Kraut, Peter Pontiac

- Le Monde d’Edena [The World of Edena], Jean “Moebius” Giraud

- Teratoid Heights, Mat Brinkman

______________________________________________

Mike Hunter

Contributing writer, The Hooded Utilitarian

“Here,” Richard McGuire

- From Hell, Alan Moore & Eddie Campbell

- “Here,”, Richard McGuire

- “Hypothetical Quandary,” Harvey Pekar & R. Crumb

Counted as a vote for American Splendor, Harvey Pekar, with R. Crumb, et al. - “L,” Eric Drooker

- “Patton” and “The Religious Experience of Philip K. Dick,” R. Crumb

Counted as a vote for The Weirdo-Era Stories, R. Crumb - “Secret Lords of the DNA,” Del Close, John Ostrander, and David Lloyd

- “Ten Minutes”, Will Eisner, with Jules Feiffer

Counted as a vote for The Spirit, Will Eisner - “Those Who Change,”, Stan Lee & Steve Ditko

- Watchmen, Alan Moore & Dave Gibbons

- “What the Left Hand Did,” Jim Woodring

Counted as a vote for The Book of Jim, Jim Woodring

______________________________________________

“Illogical Volume”

Contributing writer, Mindless Ones

“Lint,” Chris Ware

- The Alec Stories, including/especially The Fate of the Artist, Eddie Campbell

- Birdland, Gilbert Hernandez

- The Fourth World Stories, including/especially The Hunger Dogs, Jack Kirby, with Mike Royer, et al.

- The Invisibles and The Filth, Grant Morrison & Steve Yeowell, et al.

- Krazy Kat, George Herriman

- “Lint,” Chris Ware

- Pluto, Naoki Urasawa

- Solo #12, Brendan McCarthy, et al.

- Transformers: Time Wars, Simon Furman, et al.

- The X-Force Stories, Peter Milligan & Mike Allred, with Laura Allred

______________________________________________

Domingos Isabelinho

Contributing writer, The Hooded Utilitarian

The Cage, Martin Vaughn-James

- Amapola Negra [Black Poppy], Héctor Germán Oesterheld & Francisco Solano López

- The Cage, Martin Vaughn-James

- Conte démoniaque, Aristophane

- Die Hure H [W the Whore], Katrin de Vries & Anke Feuchtenberger

- Journal (3), Fabrice Neaud

- Le Journal de Jules Renard lu par Fred [The Diary of Jules Renard as Read by Fred], Jules Renard & Fred

- Mûno no Hito [The Talentless Man], Yoshiharu Tsuge

- La orilla [The Shore], Elisa Galvez & Federico del Barrio

- Sa-Lo-Món, Santiago “Chago” Armada

- Zil Zelub, Guido Buzzelli

COMMENTS

Here’s my top ten (restrict comics field). If my top ten included things from the expanded field it would look quite diffrent with things like: Jacques Callot (Les Misères et malheurs de la guerre [The Miseries and Misfortunes of War]); Francisco de Goya (Los Desastres de la Guerra [The Disasters of War]), Los Caprichos [The Caprices]); Katsushika Hokusai (Fugaku Sanjûrokkei [Thirty-Six Views of Mt. Fuji], Fugaku Hyakkei [One Hundred Views of Mt. Fuji]); Charlotte Salomon (Leben? oder Theater? [Life? Or Theater?]); Francis Bacon (Triptych May-June 1973); William Hogarth (A Harlot’s Progress, A Rake’s Progress); Pablo Picasso (Songe et mensonge de Franco [Dream and Lie of Franco]).

______________________________________________

Cole Johnson

Cartoonist, Sleepover Comics

Tricky Cad, Jess

- The Bungle Family, H. J. Tuthill

- Buzzbomb, Kaz

- Cowboy Henk, Herr Seele and Kamagurka

- Maria no Komon [Mary’s Asshole], Hanako Yamada

- Nancy, Ernie Bushmiller

- Nekojiru Udon, Nekojiru

- Remue Ménage, Anna Sommer

- Rthym Mastr, Kerry James Marshall

- Tricky Cad, Jess

______________________________________________

“Jones, One of the Jones Boys”

Writer, Let’s You and Him Fight

Thor, Jack Kirby & Stan Lee

- The ACME Novelty Library, Chris Ware

Counted as a 0.25 vote each for “Building Stories,” Jimmy Corrigan: The Smartest Kid on Earth, Quimby the Mouse, and Rusty Brown, including “Lint” - Cerebus, Dave Sim & Gerhard

- Donjon [Dungeon], Joann Sfar & Lewis Trondheim, et al.

- The Frank Stories, Jim Woodring

- Fungus the Bogeyman, Raymond Briggs

- The Little Lulu Stories, John Stanley & Irving Tripp

- Little Nemo in Slumberland, Winsor McCay

- Seven Soldiers of Victory, Grant Morrison, et al.

- Thor, including “Tales of Asgard”, Jack Kirby & Stan Lee, with Larry Lieber, et al.

- Various manga, Shintaro Kago

COMMENTS

MASSIVE DISCLAIMER: You’ve asked for “the ten comics works you consider your favorites, the best, or the most significant,” and this is a list of my favourite comics as of 29 June 2011. It sure as hell isn’t the ten “best” comics!

______________________________________________

Bill Kartalopoulos

Instructor, Parsons The New School for Design; programming coordinator, Small Press Expo; contributing editor, Print magazine

Histoire d’Albert, Rodolphe Töpffer

- Alias the Cat, Kim Deitch

- Caricature: Nine Stories, Daniel Clowes

- The EC Comics War Stories, Harvey Kurtzman (the stories Kurtzman drew himself)

- “Here,” Richard McGuire

- Histoire d’Albert [The Story of Albert], Rodolphe Töpffer

Counted as a vote for Works, Rodolphe Töpffer - Krazy Kat, George Herriman

- Maus: A Survivor’s Tale, Art Spiegelman

- Paul Auster’s City of Glass, Paul Karasik & David Mazzucchelli

- Rusty Brown, Chris Ware

- Travel, Yuichi Yokoyama

______________________________________________

Megan Kelso

Cartoonist, Artichoke Tales, Queen of the Black Black

Goodbye, Chunky Rice, Craig Thompson

- 1. ONE! HUNDRED! DEMONS!, Lynda Barry

- 2. Dirty Plotte, Julie Doucet

- 3. Ghost World, Daniel Clowes

- 4. I Never Liked You, Chester Brown

- 5. Perfect Example, John Porcellino

- 6. Skibber Bee Bye, Ron Regé, Jr.

- 7. Cave-In, Brian Ralph

- 8. Shrimpy and Paul, Marc Bell

- 9. Goodbye, Chunky Rice, Craig Thompson

- 10. Palestine, Joe Sacco

______________________________________________

Abhay Khosla

Contributing writer, The Savage Critics

“Master Race,” Bernard Krigstein & Al Feldstein

- The ACME Novelty Library, Chris Ware

Counted as a 0.25 vote each for “Building Stories,” Jimmy Corrigan: The Smartest Kid on Earth, Quimby the Mouse, and Rusty Brown, including “Lint” - Calvin and Hobbes, Bill Watterson

- The Fourth World Stories, Jack Kirby, with Mike Royer, et al.

- From Hell, Alan Moore & Eddie Campbell

- Go Go Monster, Taiyo Matsumoto

- Little Nemo in Slumberland, Winsor McCay

- “Master Race,” Bernard Krigstein & Al Feldstein

- The New Yorker Cartoons, Charles Addams

- The Palomar Stories, Gilbert Hernandez

- Peanuts, Charles M. Schulz

COMMENTS

I don’t want to overthink this because otherwise this’ll turn into a thing with me… Also: I question that lists like these are a good idea. But whatever, who cares. Thanks for asking. Oh: if I have to pick just one, for The Fourth World, let’s go with The New Gods. But that would be the incorrect way of looking at that work, and not how I understand they’re being published currently, so I’m going with The Fourth World.

______________________________________________

Molly Kiely

Cartoonist, Tecopa Jane, Saucy Tart

La Perdida, Jessica Abel

- The American State Maps, Ruth Taylor White

- The Biologic Show, Al Columbia

- Krazy Kat, George Herriman

- Li’l Abner, Al Capp

- Peanuts, Charles M. Schulz

- La Perdida, Jessica Abel

- Shôjo Tsubaki [Mr. Arashi’s Amazing Freakshow], Suehiro Maruo

- Steven, Doug Allen

- THB, Paul Pope

- Viaggio a Tulum [Trip to Tulum], Milo Manara & Federico Fellini

______________________________________________

Kinukitty

Contributing writer, The Hooded Utilitarian

Seiyô Kottô Yôgashiten, Fumi Yoshinaga

- Seiyô Kottô Yôgashiten [Antique Bakery], Fumi Yoshinaga

- Calvin and Hobbes, Bill Watterson

- The Doom Patrol Stories, Grant Morrison & Richard Case, with Scott Hanna, et al.

- Gashlycrumb Tinies (and everything else), Edward Gorey

Counted as a vote for Works, Edward Gorey - Let Dai, Sooyeon Won

- Li’l Abner, Al Capp

- Peanuts, Charles M. Schulz

- Le Petit vampire [Little Vampire], Joann Sfar

- Oroka-mono wa Aka o Kirau [Red Blinds the Foolish], est em

- Scary Godmother, Jill Thompson

______________________________________________

T. J. Kirsch

Co-creator & illustrator, Uncle Slam Fights Back; illustrator, She Died in Terrebonne

David Boring, Daniel Clowes

- Asterios Polyp, David Mazzucchelli

- Calvin and Hobbes, Bill Watterson

- David Boring, Daniel Clowes

- Ghost World, Daniel Clowes

- Hicksville, Dylan Horrocks

- I Never Liked You, Chester Brown

- Krazy Kat, George Herriman

- Maus: A Survivor’s Tale, Art Spiegelman

- Peanuts, Charles M. Schulz

- The Playboy, Chester Brown

______________________________________________

Sean Kleefeld

Writer, Kleefeld on Comics

Understanding Comics, Scott McCloud

- Calvin and Hobbes, Bill Watterson

- Complete Works, Joe Sacco

Counted as a vote for Palestine, Joe Sacco - The Fantastic Four, Stan Lee & Jack Kirby, with Joe Sinnott, et al.

- The Fantastic Four Stories, John Byrne

- The Green Lantern/Green Arrow Stories, Denny O’Neil & Neal Adams, with Dick Giordano, et al.

- Judge Dredd, John Wagner & Carlos Ezquerra

- Little Nemo in Slumberland, Winsor McCay

- Kozure Ôkami [Lone Wolf and Cub], Kazuo Koike & Goseki Kojima

- Tozo the Public Servant, David O’Connell

- Understanding Comics, Scott McCloud

__________

(Looking at today’s choices) Dang, how could I have forgotten the brilliant, towering “Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary”?

Of course, there are dozens of other exceptionally worthy works that could have been dug up, with more time, research to refresh faded memories, and ones which I never got around to reading (such as “Epilectic,” which from everything else I’ve seen from its creator, would surely have been brilliant).

Which makes one think that probably the “conservativeness” of the list, and the poor showing of women creators therein (Dori Seda, Mary Fleener, Carol Lay, Alison Bechdel, Marie Severin [whose humor work in “Not Brand Ecch” was outstanding], Julie Doucet, Phoebe Gloeckner, Ariel Schrag [so fine, on so many levels!] created works as good as plenty of choices in many “top ten” lists here), is less due to factors such as sexism and willful cultural myopia, and the simple likelihood that those were the topnotch titles that most readily came to the minds of those being polled.

Alas, fame, fond youthful memories of a certain title, greater publicity accorded some creators, that the works have been around long enough to be considered masterpieces,the reality that even a voracious comics reader can only have sampled a portion of the work created throughout the world — I’ve never even heard of much that Domingo recommends, for all my years of reading “The Comics Journal” — account for “the usual suspects” routinely showing up in Best Of lists.

Anyway, for my top ten choices I decided to pick single stories (or GNs conceived of as a unified whole) because the quality is more consistent throughout. Masterpieces, all!

(Thanks so much for adding links to info about the choices, Robert Stanley Martin! Or whoever did it…)

Well, nostalgia, familiarity, and sexism aren’t mutually exclusive.

And yes, it’s Robert who put in all the links…nearly killing himself in the process, I think.

I wish I’d thought to include the Smithsonian collection, as suggested on another thread…

——————-

Noah Berlatsky says:

Well, nostalgia, familiarity, and sexism aren’t mutually exclusive.

——————-

I’m sure the folks who voted on this poll would be charmed about the thinking that they didn’t choose 50% women creators because they’re sexist.

Might as well toss in their racism as surely behind their not including the proper percentage of creators “of color.”

And, jeez, a lot of manga artist/writers are women and Japanese! Didn’t vote for them? You’re guilty of two prejudices for the price of one!

Comics has long-standing issues with race as well as with gender. Defensiveness on this point just underlines it. It doesn’t refute it.

“Defensiveness” is an easy ad hominem attack, Noah, even if sometimes justified. You use it a lot; it’s one of those words seemingly designed to shut down discussion.

“Issues” is another word I’m wary about, due to its vagueness. I’d come straight out and say ‘Comics and its fandom is blighted by sexism and racism”. We should all man up!

How ’bout this — why why why is it so hard for you (referent ambiguous – white men?) to accept the existence of institutional or structural sexism and racism, where “structural” means that they’re just part of the fabric of the culture and people participate in them whether or not they mean to, just by doing things that make sense to them from their cultural environment?

Taking it personally when people point out that we’re part of a culture that has problems with sexism and racism, and that our actions as part of that culture tie into that sexism and racism, is what I think Noah means by “defensiveness”. It takes active resistance to avoid participating in structural prejudices. Sometimes we have to choose where to put the resistance — as in the case of the Second Wave feminists, who probably didn’t MEAN to be racist, but made choices that didn’t work right for black women, through ignorance or blindness or perhaps even strategic choices to deal with white women’s problems first since there were more white women to mobilize. (I really don’t know — I am guessing it was blindness, mostly.)

But apparently it’s very hard to accept that not all sexism and racism is deliberate targeted meanness, and not all critiques of sexist and racist outcomes are personal. I don’t get why that is.

Caro, you said this elsewhere:

“But I’m sure you’ve often been the only man in a place where there were all women in positions of power, and had to deal with them unintentionally treat you differently, exclude you from their social group, require your participation in activities you don’t enjoy, make you feel like you were completely outside the system and therefore less likely to succeed no matter what you do, haven’t you? I’m sure you know exactly how it feels and how exhausting and tedious and boring it can be to navigate it all the time, right? Surely this has been your situation at work, at church, in service clubs, and here online, right? (My sarcasm of course discounts the fact that the women in that all-women environment would probably go out of their way to make you feel comfortable.)”

Caro, you are describing there the professional situation that I, a man, has had to put up with for the past 34 years.

I teach English and French as foreign languages. It is a sector overwhelmingly dominated by women. The school where I teach employs 27 women out of 30 English teachers. New hires are almost all women– I’m a legacy dinosaur, as are the other male English teachers (none under age 50.)

Women are given priority in everything. In tough times, the men are the first teachers to get their hours cut, and the first to be fired. Women socialise among themselves, excluding men; cronyism is rife.

Not a single man is in a management position.

Your satire is too close to reality for some of us to work.

And if you said that this was making you miserable enough that you couldn’t perform your job well, I’d say that is yet another argument for why integrated professional environments are important (which was the original point.) Your environment isn’t integrated either.

My husband’s experience during graduate school working in a nursing position was different — everybody was very supportive and he didn’t feel there was any institutional sexism particularly. But I think it’s far better to advocate against highly homosocial work environments, because the vast majority of the time, your situation is exactly what happens.

It just happens a lot more often to women than it does to men.

Oh, agreed, but in non-academic teaching for well over a century women have dominated.

This is a big part of the reason that non-academic teaching is such a despised and dumped on profession. Its feminization and its low status are intertwined.

———————

Noah Berlatsky says:

Comics has long-standing issues with race as well as with gender. Defensiveness on this point just underlines it. It doesn’t refute it.

———————-

So; I point out that those people asked to participate in the poll — hardly a bunch of right-wing louts — would hardly be pleased about “the thinking that they didn’t choose 50% women creators because they’re sexist,” or racist, for “not including the proper percentage of creators ‘of color.'”

And you switch to saying that “comics” (surely meaning the comics medium/industry) “has long-standing issues with race as well as with gender.”

So, are you saying that because “comics” indeed has shown far-from-ideal treatment of women and minorities, in characters or creators, that therefore means that everyone connected with it (including alt-comics folks, critics and bloggers) is equally culpable?

———————-

Caro says:

How ’bout this — why why why is it so hard for you (referent ambiguous – white men?) to accept the existence of institutional or structural sexism and racism, where “structural” means that they’re just part of the fabric of the culture and people participate in them whether or not they mean to, just by doing things that make sense to them from their cultural environment?

———————–

Who is denying, or “having a hard time accepting” that there’s plenty of “structural sexism and racism”?

Where I disagree is about the “thinking” that, because we live in a society with lots of racism/sexism, are interested or working in an art form/industry likewise tainted, therefore we are all helpless puppets who unthinkingly perpetrate outrages like…deliberately leaving women creators out of “best of” comics polls.

By that “thinking,” therefore, since flag-waving, America-is-#1, Christianity is Best, Capitalism Rules! propaganda has been taught and shoved in our faces from birth (a blatant barrage compared to which the sexist/racist messages are but a mild murmur)…

…Everyone here should be flag-waving Bible thumper, cheering on Wall Street and the Free Market, going U-S-A! U-S-A!

But we’re not, are we? Some of us have brains, and are able to learn from alternative sources of information; perceive gaps between propaganda and reality, and escape mainstream non-thinking.

(Now, watch this post get deleted, because “I’ve said it all before,” and some True Believers will be thrown in a tizzy by having their party-line “ALL whites are racists,” “ALL women are oppressed,” “ALL white men are sexist” simplicities challenged.)

BTW, though I keep referring to “best of,” Robert Stanley Martin’s wording soliciting choices also included “your favorites” (is it acceptable to have personal favorites which are not “gender-equal,” or does that automatically damn you with Dave Sim as a woman-hater?). And “most significant,” which hardly equals approval, more an awareness of blunt historic reality. Someone might detest Kirby’s or Tezuka’s work, yet only an idiot would deny they’ve been gigantically influential.

Mike says:

I didn’t say this, and in fact, specifically contradicted the notion that it was “deliberately leaving women creators out” (when I said “apparently it’s very hard to accept that not all sexism and racism is deliberate targeted meanness.”)

Did you read my comment over at the LadyDrawers thread, which I cross-posted on Shaenon’s post: https://hoodedutilitarian.com/2011/08/the-hu-lady-list/#comment-22086

The “structural sexism” is (at least) embedded in the criteria used to evaluate work, our very understanding of what cartooning is and what counts as good cartooning, as well as in things like the valoration of art from a period in history when women had little opportunity or idiomatic contexts in which to work as cartoonists, and in the nostalgia for those familiar childhood works. (Kim underlines the impact of “idiomatic contexts” in his response to me.) If you pick on the basis of those criteria, you’re probably going to pick mostly men.

And that’s sexist – but not because the people deliberately leave out women, rather because the parameters don’t really allow room for them to include women. The only way to avoid being part of that sexist framework is to recast their criteria and the window they use to view comics in a way that allows those women to emerge.

Saying that comics historically and culturally has problems with sexism is a way of noticing that sexist framework. Does it mean you have to say that work is bad? No, not necessarily. You can still evaluate comics from within that framework. But I think critics and fans need to recognize and acknowledge and think critically about the limitations of that framework. There is no justification for pretending it is neutral on sexism. Critics and fans should never say to women who challenge it or resist it “come, be more like us! we know you can do it!” but instead should say “what is it you bring to our culture and artform that might broaden our horizons and enrich our field.”

Isn’t that saying the same thing, but inverted: these masculinists should be more like the feminists? Or that male tastes should conform to female tastes, not the other way around? The tension I’m noticing is that you want to say there’s something inherently different about a woman’s approach to art, but that there’s nothing inherent in the male’s approach. I think a clearer way of putting it is that stuff that’s typically considered feminine doesn’t get as much attention as what’s typically considered masculine. That way you could dismiss, say, Karthryn Bigelow for not being appropriately feminine.

I can’t understand how wanting male AND female instead of just male reads to you as wanting only female. Unless you gender “diversity” as an inherently feminine aesthetic attribute.

I don’t think either of the approaches are inherent. Gendered approaches to art reflect cultural differences. Art is gendered because our culture is gendered. This will be true unless the gendering of our culture goes away, which isn’t likely to happen — partly because gender has some ties to biology, and partly because a lot of people actually like gender.

But comics is a field that has historically been completely dominated by male approaches — to form, to content, to voice — and it is still skewed in that direction.

So the impulse is to select for the women who do or can conform to or embrace that form, content, and voice and then call the resulting mix “diversity.” But that is a diversity of physiological gender (or sex), not a diversity of cultural gender. Sexed bodies do not uniformly map onto gendered culture at the individual level, and all you’re doing is selecting for the sexed bodies that do or can fit into the gendered culture associated with the other sex.

You can’t look at the work of a single woman and say “this is women’s art” because that woman’s relationship to gender will be idiosyncratic. But if you look at a large enough group of women in the aggreagate, you can see trends emerge that are probably related to gender.

It is certainly an achievement to make it possible for individual women’s bodies to participate without discrimination in male approaches to art. But it’s a different problem when an art is systematically equated with (reduced to?) those male approaches, rather than with a more diverse range. Addressing that — the structural sexism of a culture — is much harder.

I don’t immediately think Kathryn Bigelow’s success represents a particular achievement for women’s art — only for women’s bodies. That said, I haven’t seen the Hurt Locker, so it might have more elements of a “woman’s” aesthetic than reports indicate.

Maybe the confusion is that you’re thinking about genre rather than aesthetics? I think the formulation “stuff that generally considered feminine” doesn’t work because it implies things like “romance” or “manga” or whatever. “Feminine” has connotations of shallow gender norms, but the vantage point of women isn’t shallow at all — so that’s why it’s “things that draw on or appeal to a woman’s aestehetic.” That could be a war movie or an adventure tale just as easily as a romance or a family drama. And it’s sometimes not just the work itself that doesn’t get attention, it’s the way that work, conceived as woman’s aesthetic, speaks back to the masculinist cultural norms and broadens the field.

I don’t think the resulting outcome, a field that contains both, is gendered female. The movement is dialectical. Insofar as the masculine aesthetic is changed, it’s changed to something less gendered, or differently gendered, not to something that’s gendered the opposite way.

Noah:

“This is a big part of the reason that non-academic teaching is such a despised and dumped on profession. Its feminization and its low status are intertwined.”

It’s far more ambiguous than that, Noah. There’s also the popular image of the ‘Hero-Teacher’ as exemplified in such films as ‘To Sir with Love’, ‘Stand and Deliver’, ‘The Dead Poets’ Society’, et al ad infinitum.

The profession is ‘despised and dumped on’ from above and below, so to speak.

From above, where it’s been thoroughly documented that pedagogic excellence in academia isn’t just ignored– it is actually detrimental to teachers: the assumption being that if you actually teach classes instead of fobbing them off onto graduate TA’s you aren’t serious about research and publication. So adios tenure or promotion, Mr Chips.

From below, where appalled parents see their kids fail, and fail, and fail again at basic skills: the villain is obviously omnipotent teachers’ unions. I don’t want to paper this over, but scapegoatery is involved here, along with old-fashioned client politics (Republicans demonise all forms of public-service unionisation, as unions tend strongly to support Democrats.)

Guys, we’re doing the best we can, OK? I feel privileged because I deal in adult education, but it’s still tough going.

(And, since the bills are paid by private-sector employers,I have to face a viciously strict calculus of accountability/results that makes the most stringent public school criteria look like hippie heaven.)

A last remark to Caro: I am aware that I’m part of a particular sub-culture– or rather, sub-sub-sub-sub-sub culture, like a nest of Matrioshka dolls; and my experience can’t be extrapolated to society at large.

Everything Caro says is right.

I just want to add…American comics is really up to its bits and over in masculine genre product, while female genre product has to be imported from the other side of the world. I think that’s pretty telling about where comics is at.

“But comics is a field that has historically been completely dominated by male approaches — to form, to content, to voice — and it is still skewed in that direction.”

I don’t share Caro’s view that there is such a thing as an male approach to form, which seems, to me, similar to the claim that there is such a thing as a male or female approach to language (an essentialist claim that I reject, regarding which I refer readers to the work of linguist Deborah Cameron). I think of form, rather, as something that isn’t natural to anyone, female or male, but that becomes naturalized by dint of immersion in an artistic tradition.

Caro’s point that comics’ tradition is lopsidedly, overwhelmingly, male is of course inescapable. Point taken. This is the result of social-ideological-historical factors that have shaped the rise of comics art as a profession, or set of professions rather. Consider that comic strips in the US were originally an outgrowth of popular journalism, a highly masculine/masculinist profession at the time and even a touch disreputable (per the social conventions of elite society). American comic books, too, were an outgrowth of pulp magazine publishing, of the “yellow” press or dime novel field: a field, in other words, that was just steps away from the rag trade. While women did work in the pulps, in editorial, in writing, and in illustration, their work was typically unsung, obscure. After all, pulp work was highly disreputable. Comic books became the inheritors of all that.

By contrast, children’s book publishing (and librarianship) was a field in which women more obviously exerted power and influence (see for example Leonard Marcus’s study Minders of Make Believe). The historic antagonism between children’s publishing and comic books is partly a gendered turf war, in which children’s attention was the desired turf, comics representing in the minds of many reformers a recrudescent, crudely commercial, and (to paraphrase Marston) blood-curdingly masculinist field. The pulp field, nakedly market-centered and masculinist, was a field in which women’s participation was comparatively muted. It was, simply, a sleazy field.

The historical fact is that the industries/professions that supported the emergence of comics as a distinct form were suffocatingly masculinist. That doesn’t mean (at least it doesn’t mean to me) that all the work produced under those conditions is inherently masculine in its form and aesthetics; I don’t happen to think that formal aesthetics are keyed to gender. (Genre is another matter, as Caro points out.)

I took the initial prompt here as a challenge to list some favorites of mine. My list reflects that. The fact that some of my favorite contemporary cartoonists are women (my personal list would include Barry, Bechdel, Doucet, the sadly dormant Drechsler, Gloeckner, McNeil, Medley, Simmonds, Tyler, recently emergent talents like Eleanor Davis and [no relation] Vanessa Davis, and, to me, new discoveries like Goblet) doesn’t really faze my list of “favorites,” I’m afraid: my favorites are an archaeological record of my personal history of involvement with the form, and are works that have touched me personally. That they are mostly by men is a notable fact but not, in my view, an endorsement of a masculinist over a feminist aesthetic.

Where I differ from Caro is that I don’t see comics aesthetics as a symptom of structural sexism, because I don’t see traditional cartooning as simply and unproblematically an expression of a masculine aesthetic. That traditional cartooning is historically rooted in a profoundly sexist profession is, from my POV, an indisputable fact, but I don’t share Caro’s view that this historical fact necessarily defines an absolute gendered division in aesthetic norms.

Caro argues that prevailing aesthetic standards for comics are not neutral on sexism, which I take it means that prevailing comics standards are “structurally” sexist. But I disagree with this, because I believe that the same aesthetic that helps me make sense of Jack Kirby also helps me make sense of Anke Feuchtenberger. Obviously, I need different tools and different kinds of information to appreciate to such radically different artists, but in my view there is also a comics studies mindset that is neutral with respect to gender that I can use to begin understanding both.

Caro, I’m pretty certain you disagree with this, because you and I have had conversations before about the necessity of liberating contemporary comics/graphics practice from historically situated notions of comics. At least I take it that that is part of what you were arguing in response to the HU thread on my book, though you know that I’m inclined to disagree there. To me the aesthetics of comics derive at least in part from their native history, one in which sexism, regrettably, has played a huge part but one that I don’t feel at liberty to ignore.

I understand the risks attendant on trying to place, say, Feuchtenberger within a tradition that, in many ways, she consciously rejects, but as a comics historian I still feel bound to make that effort.

I’m with Virginia Woolf on the necessary androgyny of creative endeavor, and I do believe in the gender-neutrality of literary and artistic form. This is part and parcel of my rejection of the “ecriture feminine” argument in contemporary critical theory.

But the historical argument regarding entrenched sexism in the comics field(s) remains potent and extremely important.

PS. I don’t mean to imply in the above that women were by nature (shudder) shy of working in “disreputable” or “sleazy” fields. I only mean to say that their participation in such fields was socially discouraged and/or seldom acknowledged. No essentialist view about “what women like” is meant in the above!

I loves my Irigaray!!! But I don’t buy the Anglo-American critique, which you echo here, that it’s essentialist…

I’m actually in the middle of writing that long-ago-promised post on the post-medium condition, Charles, so I’m going to put off responding as fully to you as the comment deserves until that is posted, because I’m thinking about my response from that perspective and there’s no point in repeating myself.

I will, however, say that I think it is just as valid critically to look at Kirby from the aesthetic more native to Feuchtenberger.

It’s not either/or — richness comes when there’s both/and. To me what’s at stake is whether the “comics studies” mindset has one strict definition — or a plurality of functional ones, through different windows and lenses. Pace Delany (and my comment to Kim), I greatly prefer the latter!

Entirely sympathetic with your call for a plurality of functional descriptions rather than an oppressively airtight strict definition! To paraphrase Aaron Meskin here, down with the definitional project! Yes.

Caro, what I’m reacting against, I think, is the potentially essentialist application of an aesthetic that seeks to define the feminine by contradistinction from the masculine, in the process making some women, in effect, champions of a specific gendered aesthetic and others, well, apostates because their work doesn’t cleave to a gender-centric norm.

Tacking in a different direction:

Whereas Irigaray herself can surely be read in a (nuanced, subtle, labor-intensive) way that puts paid to essentialism, the practical effect of teaching Irigaray et al. is often a reinforcement, even if inadvertent, of gender essentialism. Too often.

This bugs me, as does the idea that writing (a practice natural to no one) is automatically gendered masculine unless and until disrupted by feminist practice. I see no empirical basis for assuming that writing, the logos, analysis, formal logic, etc., are the province of men primarily. In fact the habits inculcated by scholasticism (a notoriously male province until recently) often cut against the grain of traditional masculinist stereotypes, and some of the intellectual fields criticized most persistently for their putative “phallogocentrism” are among the most open to the participation and influence of women. So the whole emphasis on language, or literary language, or analytical language, as inherently or preemptively “masculine” strikes me as a red herring.

Whatever the sophistication and nuances of a particular writer (e.g. Irigaray), the practical social effect of certain kinds of feminist analysis, in my experience, is to reinscribe and insist upon essentialist myths that, IMO, have no historical basis. I’m an old-fashioned humanist and universalist who insists that literary and artistic work have a potentially universal and androgynous reach–and it’s on these terms that I admire and enjoy artists like Feuchtenberger, etc. They’re enlarging my understanding of, dare I say it, the human experience!

Charles, I don’t disagree that teaching Irigaray is really hard for that reason. But there’s plenty of historical evidence for gendered aesthetics — the earlier comment about romance stories versus adventure stories as an example. What so often happens with the universalist position is that it is used as a rationale for pushing women into masculinist modes that aren’t comfortable for them — because as appealing as androgyny and universalism are conceptually, practically speaking the culture is still pretty gendered, and in comics especially “the feminine” is still harder to find than historically masculinist modes.

I think the thing that makes Irigaray (et al.) hard is that it requires a radical separation of sex and gender, a very deep acceptance and committment to the idea that sexed bodies can be either gender, not just the one that corresponds to their sex, and that culture can have a gender independent of the sexed body that makes it. It’s hard for people to hear “gendered female aesthetic” and not hear “the aesthetic of all women” or “an aesthetic natural to the consciousnesses in female bodies” but it’s necessary to make that separation. “Woman” is a logical and cultural category for Irigaray, one that is most commonly found in female-sexed bodies, Western female-sexed bodies, even, but that does not depend in any way on that biological tie.

I don’t think I did a good job making my point in the first paragraph above.

As an ideal, the universalist position is great, for the reasons you describe. But too often — and I think in comics — what happens is that it is extremely difficult to tease out the elements that are universal from the elements that are gendered. The result of that is that something that’s still kind of masculine ends up getting passed off as something universal, and it’s the people who aren’t comfortable with the remaining masculine elements that are excluded — or occluded from our vision — as a result.

The benefit of examining “the Feminine” on its own terms is that it helps us see more clearly what really is universal and what is not. In the best of all possible words, that knowledge feeds into a dialectic and works toward your universality. But positing universality before that work is done seems utopian to me…

Caro, clarify for me the warrant or necessity of a gendered feminine aesthetic in the anti-essentialist context you’re describing. If, as you say,

“it’s necessary to make that separation. ‘Woman’ is a logical and cultural category for Irigaray, one that is most commonly found in female-sexed bodies, Western female-sexed bodies, even, but that does not depend in any way on that biological tie.”

On what does the necessity of the category depend, if not essentialism? What is the nature of this project, if it simultaneously highlights a gendered feminine aesthetic and yet seeks to efface gender essentialism?

If, as you seemed to be saying earlier, film director K. Bigelow’s Oscar represents a victory for someone who happens to be in a woman’s body but not for a feminine aesthetic, what are the implications of that exclusion, that distinction? I find that very problematic. By the same token, does, say, Colleen Doran’s work in comic books qualify or not for the same kinds of feminist attention given to Feuchtenberger? I think those distinctions are very dicey.

Oh lord, Charles, do you really want me to answer that? I mean, it’s going to involve a lot of Lacan LOL…

OK, let me see if I can avoid getting into technical Lacan by sticking to the second question and not answering what the category depends on (since the answer to that is specific to Irigaray and the Lacanian formulation).

Irigaray’s is absolutely a project that celebrates the historical particularity of women, of women’s experience, and of things that have historically been devalued as “Feminine” — in that sense it does not seek to erase gender. What it does erase is the idea that that those “Feminine” things are unproblematically or necessarily tied to female biology. She makes reference to female biology as a “topology” for these things in the same way that Freud makes reference to male biology and that Lacan himself makes reference to mathematical topology. But “The Feminine” is just a terrain (to stick with the topology) of aesthetics and experience — it is available to anybody who wants to seize it and enjoy it.

Although there are aspects of her project in particular that have to do with the weeds of Lacanian theory, I think you’re asking about how these ideas inform a Feminist project of larger cultural scope, and while I do think that it is ultimately to decouple those aesthetics from their historical association with those specific bodies — I think it is first to be able to see them. For Lacan, logically and structurally, “Woman does not exist.” The assumption here (in extremely colloquial language) is that because we are a part of a culture where women’s perspectives and voices have been greatly devalued, for an exceptionally long time, the very concept of “woman” is filtered through a male gaze. We cannot imagine what women would look like if we could see them on their own terms, unfiltered by the perspective of the male. So Irigaray’s project is imagining what women would look like if we could see them truly on their own terms. That’s why, to me, there is so much aesthetic resonance between French feminism and feminist sci fi — both are fantastic utopias. They celebrate historical categories as if they were not historical, not to assert their essentialism but in order to release our imaginations from the limits of history. I see that as very similar to the way many other feminist projects are about releasing our bodies from oppressive historical and cultural norms.

Practically, though, I didn’t mean to suggest that I thought Feuchtenberger was some sort of archetypal feminine cartoonist and no comic except comics like hers are feminine — I do think Feuchtenberger is particularly close to Irigaray and Cixous’ notion of ecriture feminine, but that French feminist concept is only one strain of women’s writing. I wouldn’t advocate for excluding any women — including the ones who worked in the hyper-masculine aesthetic of the comics industry in the ’50s and ’60s — from a rigorous academic project to examine women’s voices in comics and explore the ways in which those works, examined together, challenge and nuance and potentially transform our understandings of the aesthetics of the form. Feuchtenberger is just an easy object of study for feminists because she is so self-consciously feminist, but to say that she should get more attention is like saying that feminists should only read Margaret Atwood and Erica Jong and not George Eliot or Jane Austen…which would be patently ridiculous.

At the moment, though, she gets significantly less attention than women who work in the more historically defined idiom, and I think that is definitely wrong. But that’s the kind of strangled imagination and vision that Irigaray’s project is designed to correct.

My point about Bigelow was just that her being a female director doesn’t necessarily entail that she works in a feminine aesthetic; I haven’t seen the Hurt Locker so I just don’t know whether it’s straight traditional male genre war film or not…I’m definitely not intending to make any claims about the film’s engagement with any feminine aesthetic, Irigaray’s or the Second Wave’s or otherwise…just to say that having a woman director does not automatically mean that it does engage that aesthetic in any way.

Something that’s still ambiguous: I think this idea of “seeing women on their own terms” doesn’t deny the fact that the present reality of women is shaped by patriarchal historical forces. In many ways, politically, it’s “let’s not throw the baby of femininity out with the bathwater of gender oppression”, reacting against that aspect of the Second Wave where women “wore the pants.” Jarvis Cocker once remarked, criticizing Labour, “A classless society does not mean one where everyone is middle class,” and the parallel is “a genderless society is not one in which everybody is male.”

So perhaps a pithier statement is that the project involves thinking about how to make men and women more equal without necessarily making women more like men. That shouldn’t require constructing a Matriarchal society equivalent to the Patriarchal one we’ve got now — but it does involve a dialectic, which is inherently anti-Essentialist.

I don’t know whether any of that answers your question or not. :|

Charles, just to maybe try to summarize/add to what Caro’s saying:

There’s a humanist feminism the goal of which is broadly to make everybody equal in a kind of idealized democracy. This is an extension of enlightenment ideals, basically; it’s a vision of a society much like the one we’ve got, where the promises of the American democratic dream are fulfilled.

There’s also a radical feminism that argues that the dreams of society as we have them, the enlightenment notions of equality and democracy, are fundamentally patriarchal. From that perspective, feminism’s goal is not to integrate women into society, but to revolutionize society from a female perspective.

I don’t think it’s right to say that one of these is essentialist and the other isn’t. Rather, the first essentializes a human nature; the second essentializes gender. That’s why Irigary at times seems like she rejects all essentialism, and at other times seems extremely essentialist.

The point of Irigary’s feminist project is that lots of feminists (even Virginia Woolf) have argued at various moments that integrating women into patriarchy is not in itself ideal. A patriarchy with women equal is still (many feminists argue) unjust. Feminism isn’t just about making women equal; it’s about changing the terms of the debate. Which, for example, might point out the ways in which superheroes embody patriarchal fantasies, and try to undermine that or replace it with different subject matter (which Marston/Peter did in one way, and Feuchtenberger does in another way, and arguably shojo in an American context does in another way.)

It’s worth pointing out too that denying gender essentialism can itself turn into an essentialism which can be oppressive. Even if gender is social rather than biological, it’s a really solid, ineluctable social fact which majorly defines every aspect of people’s experience, whether they be men, women, both or neither. Acnowledging that isn’t oppressive; in many cases, it’s the first step towards dealing with oppression.

————————

Caro says:

…The “structural sexism” is (at least) embedded in the criteria used to evaluate work, our very understanding of what cartooning is and what counts as good cartooning…

————————-

So “our very understanding of what cartooning is and what counts as good cartooning” is inherently sexist? To appreciate qualities such as wit, rendering skills, originality, narrative ability, characterization, imagination is sexist, because those are supposedly male attributes?

Your comment from another thread:

————————-

If we need to codify and celebrate and advocate a separate tradition of “women’s cartooning” with its own aesthetic and cultural criteria in order to be able to roar these women’s names as greats in comics, then so be it…

————————-

So as with sports, we need to segregate women creators, because they inherently can’t compete with males on an equal footing? Funny how women film directors (proportionately few though they may be) or women writers, choreographers, etc. have no problems doing so…

And what would be the ingredients in a “women’s aesthetic”? (Sarcasm alert) Big emphasis on sisterly bonding, food, open displays of emotion? Focus on the bodily and biological instead of ideas and the intellectual? On motherhood and raising children? Lowered emphasis on male traits like linear narratives and logic?

(Ah, the hubbub that would result if it was some nasty, sexist pig like me suggesting there’s such a thing as “women’s art”! But because it was a feminist saying it, then we get “Everything Caro says is right.”)

I’m reminded of the fiasco that was Ebonics, the thinking being that, because black kids were doing so poorly in English, therefore they needed a grammar of their own. Never mind that being fluent in “Ebonese” would hardly improve their hiring prospects in the world beyond the ghetto.

And “its own…cultural criteria”? Because women all share the same culture? Personally, I’m betting that culturally, Muslim women have more in common with Muslim males than with WASP women; who in turn have more in common with WASP males than African tribal women, and so forth.

————————

You can’t look at the work of a single woman and say “this is women’s art” because that woman’s relationship to gender will be idiosyncratic. But if you look at a large enough group of women in the aggreagate, you can see trends emerge that are probably related to gender.

———————–

A defensible argument, but what a can of worms it spills forth! Are Mary Cassat, with her soft, fuzzy renderings of women tending kids, Judy (“The Dinner Party” Chicago and Frida Kahlo (lots of soul-baring emotion, focus on the biological) more representative of “women’s art” than Louise Nevelson ( http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Louise_Nevelson ), Käthe Kollwitz, Alice (as unflattering a portraitist as Lucian Freud) Neel?

And what a “with friends like these…” approach this is! Can some mainstream comics editor now say to an aspiring female comics creator, “Sorry, I’d personally love to assign you this career-making high-profile superhero gig, but these feminists say because you’re a woman, your ‘own aesthetic’ and ‘culture’ means you’re unsuited for the job!”

———————–

…that’s sexist – but not because the people deliberately leave out women, rather because the parameters don’t really allow room for them to include women. The only way to avoid being part of that sexist framework is to recast their criteria and the window they use to view comics in a way that allows those women to emerge.

————————

Yes; we have to reshape our entire aesthetic criteria and the way we view comics in order to “allow” (because they must passively wait for the opportunity to be handed to them) women to make a better showing…

———————–

…what I think is sexist is the demand that women work in that tradition and only that tradition in order to be considered great…

———————–

Alas, by Domingos holding up all manner of other approaches and views of what makes “comics” ( https://hoodedutilitarian.com/2011/08/comics%E2%80%99-expanded-field-and-other-pet-peeves/ ) — the creators referenced overwhelmingly male, natch — the parameters of your ideal “women’s art ghetto” just shrank some more…

The difference with sports is that sports are games with very specific rules and judging criteria. Aesthetics aren’t like that. The fact that you need to pretend that aesthetics are sports in order to sustain your indignation is a strong indication that you need to think through what you’re saying more carefully.

Feminism offers a challenge to aesthetic criteria. For example, wit (which is in comics underground tradition often specifically misogynist) and originality (how original is a medium which is obsessively focused on a male perspective?) are both culturally determined concepts, not absolutes. “Objective” aesthetic criteria aren’t objective; they’re socially and culturally determined. Feminism and women creators potentially call into question those criteria.

It’s not a question of lowering standards to admit women’s work. Rather, the issue is that women’s work challenges those standards, in part because women’s experiences have been different than those of men. That doesn’t mean that all women are the same, or that there aren’t profound differences between women. It just means that there is something to feminist ideas of sisterhood — an idea that you, and many men, seem to find really upsetting.

——————–

Noah Berlatsky says:

…The fact that you need to pretend that aesthetics are sports in order to sustain your indignation is a strong indication that you need to think through what you’re saying more carefully.

———————-

How did I “pretend that aesthetics are sports”?

And rather than being indignant — I’d save that reaction for issues that are truly important, like the lack of universal health care in the richest country in the world — my mood is more one of head-shaking bemusement. Indeed, some liberals and feminists do their damnedest to act like right-wing caricatures…

————————–

Feminism offers a challenge to aesthetic criteria.

————————–

Yeah, right…

————————–

For example, wit (which is in comics underground tradition often specifically misogynist) and originality (how original is a medium which is obsessively focused on a male perspective?)…

—————————-

Note the subtlety with which “wit” and “originality” are tainted with loathsome male attitudes! Why, an anti-Science Bible-thumper could say,

“For example, technology (which was used by the Nazis to create the means to massacre millions) and the scientific method (which was used to rationalize their elimination of undesirables for “racial purity”)…”

————————–

…are both culturally determined concepts, not absolutes.

—————————

So something is either a wholly “culturally determined concept” or an “absolute”? Mr. A, meet your Theorist compatriot…

—————————

“Objective” aesthetic criteria aren’t objective; they’re socially and culturally determined.

—————————

They are neither wholly culturally determined (despite variations, concepts of, say, female beauty/male handsomeness are pretty much consistent worldwide) nor wholly objective. (Who said they were “objective”? Call me Mr. Grey…)

——————————

Feminism and women creators potentially call into question those criteria.

It’s not a question of lowering standards to admit women’s work. Rather, the issue is that women’s work challenges those standards, in part because women’s experiences have been different than those of men…

——————————

I guess that “potentially” is there to explain why the work of countless women’s creators and feminists have accomplished bupkis in challenging the aesthetic status quo. Indeed, if anything — take a look at the mass media, at the pneumatic, pornface-wearing “heroines” in modern comics — things have gone backwards…

——————————–

…It just means that there is something to feminist ideas of sisterhood — an idea that you, and many men, seem to find really upsetting.

———————————-

Yeah, I’m really shaking…with suppressed laughter! Alas, the biggest dickheads making my wife’s job hell for the last five years are members of the “sisterhood”; most female genital mutilation is performed by women; mothers whose husbands/boyfriends sexually abuse their daughters routinely turn a blind eye or even excuse the abuse…

“I guess that “potentially” is there to explain why the work of countless women’s creators and feminists have accomplished bupkis in challenging the aesthetic status quo.”

Actually, there’s been a massive change in aesthetic presuppositions over the last century, much of it pushed forward by feminist thinkers. Many more women are in the canon, and attitudes towards gender and ideas about gender are taken much more seriously than they once were.

And if you don’t find sisterhood upsetting, it’s unclear why every single time it comes up on HU, you write 1000 word plus screeds denigrating it, insulting it, and generally denying it can have any possible application or utility. Every time any feminist issue comes up, you write and write and write about how the people to blame are women themselves for not being tough enough, or for being bound by ideas of maternity. Every time someone suggests that maybe, possibly, men are responsible for patriarchy, and that structural factors create difficulty for women, you freak the fuck out at extended length.

If the idea of sisterhood doesn’t bother you, then maybe the next time it comes up you can not freak the fuck out. I will wait with eagerness for that moment.

In the meantime, Caro isn’t going to be able to comment anymore because of real life stuff, and we’re once again just going round in circles on this topic, so I”m going to try to end it and close the thread.

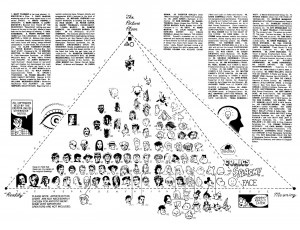

Pingback: Contextual images, part 2 | English 251: The Graphic Novel