Corey Creekmur is an associate professor of English, Cinema and Comparative Literature at the University of Iowa. He’s also a sometimes commenter, mostly over on our Facebook page. He had a bunch of interesting things to say about Habibi over there…and when he pressed he politely (if a little reluctantly) agreed to let me post them here as part of our Slow-Rolling Orientalism roundtable.

____________

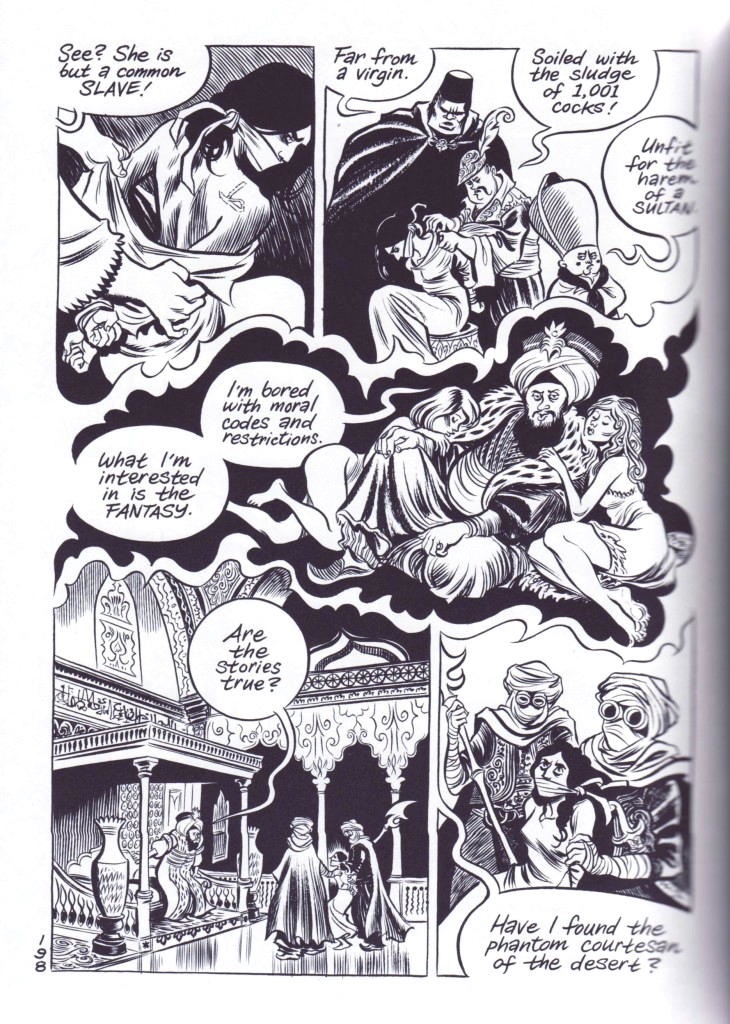

Corey Creekmur: Frankly, I think this [that is, Suat’s negative assessment of Habibi] is a response Thompson was anticipating.

Noah: What do you mean Corey? Because he mentioned his use of Orientalist tropes?

Corey: Yes, I think his risky gambit was to create a consciously Orientalist work in a post 9/11 context. The criticisms are valid, but they also presume that something “authentic” was possible, and I’m sure Thompson knew that that wasn’t really an option either. It is striking that, so far, praise for the book (in general) concentrates on the art and condemnation emphasizes the narrative, as if we haven’t learned how those intertwine.

Noah: Corey, surely it’s also possible that the art is good and the narrative not so much? Suat points out some works that he thinks succeeded better; would you disagree that that’s the case? I don’t really think Suat and Nadim are asking for more authentic so much as less racist?

Creekmur: People should read this in relation to the earlier essay you folks posted on Orientalism in SANDMAN as well. The large question seems to be what sort of Middle Eastern fantasies are now possible or tolerable in the context of the West’s increased awareness of Middle East realities. I disagree with points in these essays but they are sharp, important criticism. Thanks.

Sure, form and content don’t always mesh, but it seems striking that the positive criticism praises the art and downplays the story, and the negative criticism works in the reverse way. And isn’t a plea for less racism almost necessarily a plea for more authenticity, or realism? Again, I think Thompson risks the use of stereotypes (almost intrinsic to the history of comics) and perhaps fails in that, and does so with a certain awareness rather than ignorance. We may object to what he is doing, but my sense is that he knows what he is doing in regard to the history of stereotypes. (A friend of mine thought what he got most wrong was pregnancy and childbirth, by the way …)

Noah: Corey, would you mind if I posted our back and forth here as part of our ongoing discussion?

Corey: Um, I guess so, though these aren’t the thought-out comments the text, I think, deserves. I work on the history and function of stereotypes, but my comments here are, well, FB comments. I will note I’m bothered that people here have proudly decided not to read it at all based on the criticism. I’d rather people read it and then go after it as hard as they wish than assume that actual reading is unnecessary.

Corey: “It is striking that, so far, praise for the book (in general) concentrates on the art and condemnation emphasizes the narrative, as if we haven’t learned how those intertwine.”

This is a very important point that is on the same page with a comment I made on this very blog about no bad stories being well drawn. Take Moebius, for instance: he’s a great draftsman for many, but not for me.

This is an old problem, of course: can a text be a formal masterpiece but objectionable otherwise? In film studies the usual candidates (and I am NOT seeking to equate HABIBI with these) are BIRTH OF A NATION and TRIUMPH OF THE WILL, amazing technical achievements in the service of odious content. Again, my comments here are casual, and the book raises the need for more careful analysis, even if the result is a negative evaluation. The sheer technical skill of the work is hard to deny, but the question seems to be to what end that hard work was put. More later, I suspect …

I’m glad that this is the direction the conversation is heading. What I’d like to specify is that while Thompson may be aware of the history of stereotypes, and takes the risk of using them knowingly, there is no sense of that in the comic as a standalone object. That is what I am pointing towards at the end of my criticism. Although it isn’t a completely fare comparison (because of their differing objectives), you look at someone like Sacco and he avoids many of these pitfalls. While Sacco also draws crude Arabs, he inserts himself in the story so that readers see his subject position throughout. With Thompson there is no clear narrator throughout most of the text, so the sense of reality and fantasy is blurred (and that is arguably what he wanted to create). Again, I probably would have had a lot less problems with the book if there wasn’t an attempt to portray modernity through Wanatolia.

So for me it isn’t less racism, more reality. It is commit to either a world of fantasy or a world of reality, but don’t blend the two while using such lazy stereotypes.

That, I believe, is because you separate “art” and “content” too readily, but we’ve had that discussion before. I think it’s a frequent problem here at HU, and it persists in this discussion of Habibi.

To me, the art is entirely of a piece with the ill-advised, superficially ambitious but ultimately shallow (and unintentionally offensive) work people are describing. I don’t want to assume too much about a work I haven’t yet read though.

I’ve previously written a little about the kind of (to paraphrase a commenter in the other thread) “eye candy” art Thompson practices. Oh, and there’s also this and this, where the other comics orientalist du jour, Frank Miller, gets mentioned for comparison.

Sorry, I should point out that my first paragraph, and indeed entire post, started as a response to Domingos’ post above — Corey and Nadim posted theirs while I was writing mine.

Domingos is saying that art and content can’t be separated though…?

Suat hated the art, as far as I can tell.

For the record (as though anyone really cares) I don’t plan on reading this simply because the majority of it looks silly. Not because it’s being framed as culturally or racially offensive.

It reminds me of something a kid going through puberty would make in the middle of his Social Studies class. A little cultural content mixed with raging hormones. I’d feel the same if it was about Germans instead of Middle Easterners.

I think the artist is capable of telling a good story through his illustrations but ended up going the juvenile route with this subject matter.

It’s no “Holy Terror”, though.

Exactly Noah, thanks: can a stereotype be well drawn? Is Ebony a good drawing? Is Moebius’ fluff well drawn? Is this a good drawing?: http://tinyurl.com/6fyjb2y

Right, but you’re still judging the drawing on the basis of the content, far as I can tell. I don’t think that Frazetta cover is a particularly great drawing no, but with somebody like Moebius when he is at his best, the drawing is an intrinsic part of his exploration of creativity and matter. If you just look at the “writing”, you’re missing out.

And yeah, Noah, Suat and I are on the same page here, I think.

Domingos –

“can a stereotype be well drawn?”

Er…yes. It might not be possible for a stereotype to be well conceived (though I’m not sure that’s true either) but that’s a different question. “Well drawn” relates to craft. Craft, I think, is neutral.

“Is Moebius’ fluff well drawn?”

Absolutely. Moebius is a very accomplished practitioner of his craft. You don’t have to like the end result on every level in order to appreciate his workmanship. Or at least not unless you’re determined to cut off your nose to spite your face.

“They Call Him No-Nose!”

‘Cause with Domingos, if a comic doesn’t have great writing, then the art isn’t any good.

And, presumably (I believe he’s argued this elsewhere) if a painting doesn’t have all manner of symbolic/intellectual/emotional depth and complexity, then the rendering is likewise empty and worthless.

Thus, take that, Fragonard! ( http://www.bc.edu/bc_org/avp/cas/his/CoreArt/art/resources/frag_swing.jpg , http://www.paintinghere.com/uploadpic/Jean-Honore%20Fragonard/big/The%20Love%20Letter.jpg .)

Where is the Serious Literary Depth? Mere kitsch, to be ranked along with Keane ( http://1.bp.blogspot.com/_OvIEftacelk/TGMYPyNAKvI/AAAAAAAAA7o/8GmaP1nrrLY/s1600/Keane+Eye+mask.jpg ) and Kinkade: http://www.hiwtc.com/photo/products/18/08/17/81722.jpg .

Now, if Domingos were to say that art without symbolic/intellectual/emotional depth and complexity (or fine comics artwork in service of a mediocre story, as is virtually the entire oeuvre of Alex Toth) may still have other virtues, but just not be as good as it could be, that’d be a reasonable argument I’d heartily agree with.

But you don’t get the spiky throne of “elitists’ elitist” by being reasonable; by being able to appreciate in any way anything but the best…

I don’t really agree with where Domingos is coming from, but I don’t think it’s a crazy position or anything. In that Frazetta cover, for example — I think you can reasonably argue that part of art is imagination, and that using crass stereotypes is unimaginative and therefore that the art itself is not good. Similarly, virtuosity without depth can feel slick and vapid. That’s the objection a lot of people have to, say, Britney. The fact that the music is incredibly well put together and produced doesn’t make her critics say, “well, it’s *technically* accomplished, therefore I can appreciate it even though the content is stupid.”

I really like a lot of vapid art (like Britney or Steeley Dan) because of its emptiness and slickness — but, again, that’s an aesthetic approval based on me liking the empty content and the way it interlocks with the form, so it’s not exactly a form/content distinction.

Most people are willing to say, well I like this bit and not that bit. Domingos tends to be more absolutist — but again, I just don’t see that as being a crazy or incomprehensible position to take.

Mike: “Now, if Domingos were to say that art without symbolic/intellectual/emotional depth and complexity (or fine comics artwork in service of a mediocre story, as is virtually the entire oeuvre of Alex Toth) may still have other virtues, but just not be as good as it could be, that’d be a reasonable argument I’d heartily agree with.”

There must be some misunderstandings, then, because I agree with the above. The comics milieu favors work that is vapid or kitschy or childish over more adult accomplishments. I will acknowledge Toth’s technical skills the day people say clearly that _The Cage_ by Martin Vaughn-James of Fabrice Neaud’s _Journal_ is better than anything that Toth (or Hergé or Jack Kirby or Moebius) ever did.

Even if I prefer Watteau, comparing Fragonard with those other paintings is just ridiculous… If you don’t see that I can’t do anything for you…

Two more words: Yoshiharu Tsuge. We can’t forget comics’ only true genius can we?

I don’t like emptiness for its own sake or even its range of potential resonances — it’s kind of a one-trick-pony. But I also don’t think it’s as simple as technical accomplishment versus meaningful content. That works as a discussion for Britney, to a point; for me, at least there’s an appropriate medium-specific pleasure in the technical well-put-togetherness. It also works, for example, as an argument in favor of pure aesthetics in visual art. There’s plenty of visual art that I like and appreciate just because it’s well made.

But we’re talking about narrative here, and “technically well-put-together” means more than “aesthetically pleasing” in narrative. There is always a semiotic/conceptual component, because the material of narrative is language — not just words. Even well-put-together genre fiction, which is rarely intellectually deep, is more than just well-phrased sentences (it often isn’t well-phrased at all, particularly, in fact). There are a lot of ways to think about “good writing,” but all of them pay attention to concept in some fashion, to things that can be analyzed, not just experienced – the story-arc conventions and emotional satisfactions of genre, the heightened sonority and aesthetic pleasures of poetry, the interweaving of plot and character in traditional novels and of narrative and structure in experimental novels, which provide intellectual and imaginative pleasures of varying types.

The problem it seems to me that Domingos is fighting is the resistance among people in comics, including but not limited to cartoonists, to think writing matters at all. It’s the constant apologies for good art/weak writing that’s so irritating, and that feels to me like, at root, a plain old lack of respect for or interest in writing period. I wish someone would do some kind of study about the reading habits of comics professionals; I think our culture divides art and writing very dramatically and comics has sort of accepted that, too much, rather than setting itself the ambition of challenging the limitations of that binary for human expression and the insight into the human condition that artistic expression allows us. You can’t make that challenge unless your comic has writing that’s technically and artistically equivalent to the level achieved by your art. The work of Vaughn-James and Neaud reaches that level and makes that challenge. The oeuvre of Toth does not — although it’s easy enough to say it’s not his fault. But fault is entirely besides the point.

Ian S.: fair enough. If you want to call Frazetta a craftsman (and maybe that’s what he was: he just repeated his culture’s racist and colonialist tropes) I will stop judging him as an artist. Ditto Moebius, but I don’t think that he was a craftsman. Moebius was an artist. A very minor one, for sure, but he was an artist…

It’s a no-trick pony. That’s the beauty of it…

Seriously though, there are lots of nothings. The nothing that is there and the nothing that is not are just two. Britney’s emptiness is pretty different from Steely Dan’s is very different from (barf) Seinfeld’s, is different again from Beckett’s or apophatic theology. There are at least as many nothings as there are somethings.

Caro: “There’s plenty of visual art that I like and appreciate just because it’s well made.”

My problem is with the concept of “well made.” What does that mean? Are Frazetta’s Congolese people “well made”? I must also haste to say that I find the craft / art dichotomy problematic in the extreme. I was just playing the game according to Ian’s rules.

Domingos, what do you think of something like this:

http://smartmuseum.uchicago.edu/exhibitions/vision-and-communism/

It’s ideological kitsch, but it’s striking and formally beautiful — and the obvious-emotional-points it’s making (racism is bad) is one I have sympathy for, even if the broader point (the Soviet Union is great!) is not. I don’t know…I thought about you when I was looking at the exhibition, and wondered if you’d just hate it….

I don’t know about any of this “better than” stuff, but The Cage looks pretty incredible:

http://thegreatgodpanisdead.blogspot.com/2009/12/cage-by-martin-vaughn-james.html

No art work is meaningless (if for no other reason because it belongs in a social system), hence true nothingness in art is impossible. We may say that it is shallow, or something like that, but, as you say Noah, shallowness has many faces.

Tate Modern, coincidentally, is prompting a discussion related to this on their blog today: http://blog.tate.org.uk/?p=8503

It’s about the difference between craft and art, and I think it’s important because this is a problem in art in a way that it just isn’t in writing.

I think it isn’t an issue in writing because there are so many many contexts in which we “craft” language, and it’s something we do so routinely, that the merely functional uses of “putting words together” stand out as functional more dramatically. A well-written business proposal can have technically flawless — and even psychologically effective — paragraphs if the person writing it has a good grasp of grammar and vocabulary — but it isn’t art. Technical wordcraft is just the raw material you start with.

With the debatable exception of rote graphics (like Visio diagrams), visual art marks itself as less routine from the get go — there’s no equivalent in visual art to writing a memo or a grocery list, a place where the same tools used to make art are used to do something completely functional and routine, to the point their “wordness” and the technical acumen to create them is almost overlooked. But there is craft and skill in writing a grocery list — an illiterate person can’t do it at all, and there’s a discernable distinction, say, between a list by someone who can spell and someone who is just mapping letters to sound intuitively (DIY grocery list writing!). But the well-spelled list is probably less distinctive than the poorly spelled one. Technically proficient writing is unmarked. Even doodling has an expressive, created character that catches people’s attention and distinguishes it from jotting down a to-do list. So the distinction is a more difficult question.

But the consequence is that the bar is lower for Art in art. It actually really is reasonable to say that crafts can be art in the visual world — but nobody in literature thinks a well-put-together sentence or even paragraph is art, let alone a properly spelled grocery list — there are just too many contexts where that craft serves non-art purposes.

Noah:

Re. the Koretsky, I don’t even know if I hate it. I just feel indifference in front of its blunt and facile popaganda.

James: http://tinyurl.com/5sxyjoa

Okay; that was what I thought you’d say Domingos, but I wasn’t certain.

By “well-made” I meant “technically proficient.” Usually technique is definable and systematic, or it isn’t technique. There’s charm to things that aren’t “technically proficient”, but I wouldn’t use the term “well-made” to describe them.

For example, I have a basket made by Gullah women in Charleston. It’s woven, but it holds water like a bucket. There is a known, codified technique for weaving a basket that will hold water. When a basket follows that technique, it’s well-made! It’s pretty too, but I like it mostly because it reflects that technique and the achievement of people figuring out how to do that.

I don’t think there’s any need to reject the notion of technique in order to question the uses to which that technique is put. I don’t know much about art technique, though, so I can’t answer the question for Frazetta in particular. But it’s a mechanical question for me, never a semiotic one. I don’t think I would ever refer to the manipulation of semiotic representation as “craft” or “technique”, and I feel comfortable saying something is “well-made” but objectionable or even outright bad.

I take your point, Caro, but I don’t think the question is entirely beside the point in writing. You can in fact admire someone’s prose style and think that what they’re saying is idiotic. It’s even more the case in poetry, perhaps; you could be very taken with, even seduced, by the lilt of Yeat’s writing while still thinking he’s kind of a sexist shithead and finding that aspect of his work repugnant. I mean, that is kind of my take on Yeats, whose writing I love but whose politics I find really uncomfortable (as opposed to, say, Ezra Pound, whose politics are horrible and whose writing I don’t really like that much in the first place — or as opposed to TS Eliot, whose writing I love and whose politics I don’t agree with…but still find him intelligent and thoughtful, whereas Yeats’ objectionable politics are also just stupid.)

Anyway…long way about to say that while the issue is more pointed in visual art maybe, it’s certainly not completely absent in writing.

Domingos, I have to admire your stance, even if I struggle with it. As someone whose craft isn’t always up to snuff, I often admire the technical skill of someone like Frazetta. He can draw anatomy successfully in a way I can’t (at least yet), but at the same time, I often hate the use he puts that skill to. Hyperbole and a Half has some limited range (I think she draws with a track pad!), but I find her drawings charming and silly and delightful, and she’s got the technical skill of a fourth-grader sick with the flu. I don’t know what to do with that, ultimately, but my personal feeling is that I end up judging artists a lot on how successful they are at communicating a feeling, technical skill or no, but at the same time, I envy some draftsman skills of less overall successful artists.

Caro: Your point is well taken and probably relates a lot to the place of art in education. Most people aren’t taught basic art skills anymore in school, so even basic drawing seems so miraculous to most people because they think it is out of their range (“talent”). On the other hand writing on a basic technically level is taught, it’s pretty much the basis of a huge part of the educational system.

Noah: “Anyway…long way about to say that while the issue is more pointed in visual art maybe, it’s certainly not completely absent in writing.”

I see no reason to create the dichotomy at all.

As for the craft vs. art discussion, I pass, but let’s consider this: are an artist’s technical abilities enough to grant him / her canonization? In comics’ case it seems so… virtuosos are all over the place…

This has moved beyond the point I was trying to make, but I just wanted to reiterate that an artist like Moebius — or to take somebody a little different, Crumb — express themselves through their images to an extent that goes beyond mere “craft” (however you want to define that). It’s imaginative, provocative and highly original and intrinsic to their success as artists. Frazetta’s art is not even close.

And I agree with Domingos re: Fragonard, who is far from a superficial artist (you just have to look beyond the “writing” of his art, natch). Mentioning him in the same breath as those other artists is indeed ludicrous.

I just think it doesn’t become a question of art versus craft in writing, Noah. The technical elements of prosecraft just aren’t as tied to aesthetics. When you say you love Eliot’s writing, you’re probably talking about things in his style and voice that are more conceptual and less technical — as opposed to, say, his stellar ability to get down that grammatically correct relative clause. I suppose I can find some aesthetic pleasure in elegant grammar, but it’s not really the same thing as the aesthetic pleasure I get in skilled drawing — like, I like looking at those student studies where people draw the drape of a puddle of fabric, for example — that’s technique, isn’t it? It’s not art — it’s a technical skill you need to make art. But for the reason Derik points out, it’s easier to think of a drawing of a puddle of cloth as art than it is to think of a dull relative clause, because it’s a rarer skill. Sometimes when people talk about the “art” in comics drawing it seems like they’re basically being impressed by good technique.

That just doesn’t happen in writing. Poets don’t get credit, say, for successfully crafting lines in iambic pentameter; they get credit for what’s in those successfully crafted iambs. The technique is a baseline; art is more than that. Of course, we can debate anything, so we can argue about where the line between technique and art is, but it’s easier in writing to say “iambic pentameter is technique, what you do with that pentameter is art.”

I agree strongly with Derik’s comment: I think art education has a great deal to do with this, not only in the sense that basic art skills aren’t taught, but also in the sense that art schools, and particularly cartooning programs, rely too much on those “basic writing” skills from public education. Writing education at the pre-college level is good enough to create technically proficient writers at a baseline level; it’s not good enough to create literary writers, even of the genre fiction ilk. Good writers read more widely and study writing a great deal more than the baseline level taught in US schools.

Pre-college programs need to teach art, and cartooning programs need to teach writing. And art comics needs to get over its anxiety about collaboration and its generalized suspicion of prose, especially fiction. Until those things happen, Domingos will continue to sneer at American comics. ;)

Domingos, something is being lost here. When you say “are an artist’s technical abilities enough to grant him / her canonization? In comics’ case it seems so… virtuosos are all over the place…”, you’re essentially asserting that technique is not Art, that virtuosity is something different, and insufficient. I agree with that.

But you’re also saying you don’t accept the dichotomy…dichotomy between what? It can’t be the dichotomy between technique and Art, because then the canonization of virtuosos would be fine…

I think only the apocalypse would stop Domingos from sneering at American comics.

I’m still not convinced re craft and writing though. A lot of what you respond to in poetry especially is sound and rhythm. As Domingos says, separating that and conceptual matters often isn’t very helpful…but if you’re going to talk about craft in visual art, I don’t see why rhythm, rhyme, structure, etc. in poetry doesn’t count too.

It’s interesting that you should say that, because the only people I know of in literature who will say that the sound of a poem is more important than what it says are the Beats. And you hate them.

But to be clear — I think rhythm, rhyme and structure ARE the craft of poetry. It’s not that they aren’t craft. It’s that nobody who is serious about writing thinks that craft is enough. Nobody ever asks, “is this craft or Art?” like the Tate asks. Craft is always a baseline, never the measure of the art. Those elements mark something as poetry, to a point, but they don’t signal art.

For example, here’s the iambic pentameter generator: http://www.freewebs.com/randomator/randomiambic.html Nobody in literature is going to argue that those poems are “literature.” Some people might polemically say that in order to challenge the notion of literature. And there’s value in that to a point — but not to the notion that the iambic pentameter generator is all we need, that there is no longer any merit to people working in the form making poems that do more than something you can write an algorithm for.

It’s actually harder to write an algorithm to generate gramatically correct complex non-poetic paragraphs. Poetry, in that sense, at that level of craft, takes LESS craft than prose, because it isn’t trying to manage something systematic against something organic. So much of its form is more closely related to music than to language. But the conclusion from that is that such poetry, poetry reduced to craft, is like the Czerny and Hanon exercises for piano, which teach elements of technique and theory. They are also pleasurable, very fun to play, but still technique. Not the same as a Mozart sonata, which combines those elements of technique in interesting ways and adds concept on top.

This gets to the distinction Domingos makes about adult writing — with the exception of Beat poetry, where it’s really a conceptual reference to Jazz and a challenge to medium-specificity, most of the poems you find where those elements of poetic technique are the most important part of the poem are poems for children, just like Czerny and Hanon are for students.

The ability to do the technical things in writing and with language is a baseline expectation, largely met by elementary education. The ability to do technical things in art (and music) is not. A lack of widespread education is not an excuse for pretending there’s no distinction between technique and the brave or inspiring things made by means of it.

Matthias: “And I agree with Domingos re: Fragonard, who is far from a superficial artist (you just have to look beyond the “writing” of his art, natch). Mentioning him in the same breath as those other artists is indeed ludicrous.”

This is interesting indeed. When you say “writing” in a painting you seem to mean the subject matter. Comics taught me that the visual writing is a lot more than that. The visual writing in an image is characterization, the character’s mood, what’s s/he doing, how is s/he doing it, where is s/he doing it, what’s s/he wearing, what’s his/her social status, etc… etc… lots and lots of details that go well beyond subject matter.

Caro: I mean the dichotomy between words and images.

OK, that makes sense; thanks. Perhaps I’ll wait on Matthias’ response to your last before I comment further, as I think it’s related.

Caro and Noah:

You may be surprised to notice that, after counting my favorite comics per country, here’s the result (I couldn’t avoid lumping together short stories and series spanning decades):

U.S.A. – 38

France – 27

Belgium – 15

Argentina – 14

Spain – 13

Canada – 10

UK – 10

Italy – 9

Japan – 8

Germany – 8

Portugal – 3

Israel – 2

Cuba – 1

Holland – 1

Domingos, the important list is the one of comics you hate! :D

But it was mostly that I’ve just had this conversation with you about American comics, more than my claiming you don’t sneer at other kinds.

Domingos –

“If you want to call Frazetta a craftsman (and maybe that’s what he was: he just repeated his culture’s racist and colonialist tropes) I will stop judging him as an artist. Ditto Moebius, but I don’t think that he was a craftsman. Moebius was an artist. A very minor one, for sure, but he was an artist…”

I don’t accept that one must be either an artist OR a craftsman (craftsperson?). Unless a creator’s involvement in their art is purely conceptual, they are both of those things. Furthermore, I don’t see “craftsman” as a pejorative or a lesser title (as you seem to).

It’s perfectly possible to appreciate and enjoy a piece of art on one level whilst disliking it on another. Indeed, the conflict between what you like and what you don’t can make the work far more interesting than it would be if it accorded precisely with your standards.

I don’t think it’s either healthy or helpful to think of art as a binary system in which everything is either a “masterpiece” or complete dross. I think it’s particularly unhealthy and unhelpful if Domingos Isabelinho is the only one who gets to choose which is which.

I choose nothing, it’s the world outside of the comicsverse that chooses to ignore it. I just applaud their good taste.

I see. So “the world outside of the comicsverse” pays less attention to Moebius than to Tsuge? Really?

Tsuge is a cult figure in Japan, but forgetting that, the reason why great comics artists are ignored is because they’re not what comes to most people’s minds when they think about comics. Harvey Pekar saw it perfectly: comics readers didn’t buy his comics (they were too busy reading pulp) while lit readers and gallery goers (etc…) knew nothing about him. I keep hearing that things improved in the last, say, two decades… Maybe they did, but that’s not enough. Being a comics artist (for real, I mean) is still kind of a dead end.

Some people in the comics milieu say that there are biases against comics, etc… I just say that these biases are more than justified when Supes and Asterix and Astro Boy, etc… are the most visible part of the art form.

Asterix is great, damn it.

That’s the first time I’ve seen you go after Tezuka, I think? (Maybe I’ve forgotten.) I must admit I’ve never seen anything by him that really sent me (though I haven’t read Astro Boy.)

Domingos will go after anything that isn’t in a high-art register, Asterix and Astro Boy be damned.

Regarding the notion of “writing” in a painting, it was very toungue in cheek, but as you say, Domingos, it may be of some use in figuring out how most responsibly to treat the form/content issue when dealing with visual art. And I agree with your characterization of how it all goes beyond “subject matter.”

I mean, look at those two paintings: sure, you can say a lot of what makes them interesting is their treatment of social reality and gender roles in 18th-century France, and in human life in general, and you wouldn’t be wrong, but if you stop there, you miss out on the sheer celebratory vigour with which they’re painted, the beauty of their conception, their vision of the world.

That’s *not* just craft to me, but art of a high order. And not just because it is part and parcel of the “subject matter” or “writing” of the paintings — which it of course is too.

The same goes for Crumb and Moebius, or Hergé and Franquin, and a good number of other cartoonists, when they’re at their best — even Toth to an extent (if less so in my book). It’s akin to what Noah and Caro are describing when talking about what constitutes poetry beyond the content of the words used — rhythm, rhyme, structure, sonority, originality, imagination, vision.

I realize that this is all terribly subjective, but all aesthetic appreciation is. That’s the beauty of it.

“Tsuge is a cult figure in Japan”

So is Moebius. Just not necessarily with the sort of intellectuals you’re desperate to be associated with.

“I just say that these biases are more than justified when Supes and Asterix and Astro Boy, etc… are the most visible part of the art form.”

No. We need *more* comics like Asterix and Astro Boy, not fewer. That is to say; more comics that are appealing to children (who might one day grow up to read Tsuge, yes?), more comics that can become relevant and appreciated – beloved even – well outside fanboy circles, more comics that have mass popular appeal whilst still being interesting and / or accomplished on a formal level. Or can Tezuka and Uderzo “not draw” either?

Better that, certainly, than appealing to a few hundred snobbish, self-appointed cognoscenti and excluding absolutely everybody else. Which is what you seem to want.

“Better that, certainly, than appealing to a few hundred snobbish, self-appointed cognoscenti and excluding absolutely everybody else. Which is what you seem to want.”

Maybe take a breath?

Domingos is pretty upfront about his interests and standards. He’s also upfront (and he’s right) that his viewpoint — basically unapologetic elitism — has *no* (that’s “no”) traction, either in comics or basically in any of the arts at the moment. Given that, it’s hard for me to understand why he provokes such vitriol. So he doesn’t like Astro Boy. So what? This is going to harm Astro Boy’s reputation how?

On the other hand, there really aren’t enough people who like Tsuge, and Domingos’ advocacy for creators like him seems really valuable and worthwhile. Moreover, having *somebody* whose skeptical of certain sacred cows seems like its worthwhile too; you can see aspects of their work you might not have if you’re exposed to a different perspective.

I want more comics for kids too, Tiny Titans is one of my favorite books out there right now. It’s hard for me to want more of Superman, though. He’s always been a dumb idea, and never really generated much in the way of decent comics. I’d much rather have more Asterix, which is well-written and well drawn, than Superman, which initially and for the most part since has been neither.

————————-

Noah Berlatsky says:

I don’t really agree with where Domingos is coming from, but I don’t think it’s a crazy position or anything. In that Frazetta cover, for example — I think you can reasonably argue that part of art is imagination, and that using crass stereotypes is unimaginative and therefore that the art itself is not good…

————————–

What I found eye-jabbingly objectionable in that old Frazetta comic cover ( http://tinyurl.com/6fyjb2y ) was that the composition was a chaotic muddle!

Re his use of stereotyping (and the woman in peril from the lustful Other trope, widely used in SF pulps as well), that’s also a defensible approach from the commercial point of view: an easily-defined threat to the hero, from an enemy made to look threatening (as opposed to some folks looking as dignified as Sidney Poitier), with the virtue of the sex-object heroine in danger as well.

The splendid Romantic painter Eugene Delacroix did canvases that could be called “Orientalist” (in the later, critical meaning), such as “Combat Between the Giaour and the Pasha”:

————————–

Pieced together, the fragments of Byron’s “Turkish tale” yield a story that combines doomed love with the clash of civilizations. A “Giaour” in the eyes of his antagonist (“Giaour,” Byron explains in a note, means “Infidel”), the Christian hero of this poem goes to battle with the Muslim Hassan. His aim is to avenge the memory of Leila, the slave girl whom Hassan has had drowned after learning that she had been unfaithful to him with his enemy.

—————————

http://hoocher.com/Eugene_Delacroix/Eugene_Delacroix.htm

…Yet also scenes motivated by an appreciation for rich “local color” and costuming, such as (shown in the preceding website):

“Jewish Wedding in Morocco”

“Jewish Bride”

“The Sultan of Morocco and his Entourage”

“Arab Saddling his Horse”

“Two Moroccans Seated In The Countryside”

“Arab Horses Fighting in a Stable”

…is all such work to be damned as imperialistically “Orientalist,” considered to be putting down the other culture as primitive and savage, needing to be “rescued” by the civilizing West? Even his “Algerian Women in Their Apartments” — while depicting a harem — is defensibly reportorial, a recording of life in another culture:

—————————-

It was the chief harbor engineer at Algiers who persuaded one of the port officials, a former reis or owner of privateers, to allow Delacroix into his own harem.

In these few hours Delacroix did several watercolor sketches, some of which are in the Louvre. Using them as a basis, he painted a large picture on his return, and exhibited it in the 1834 salon. He wanted to show the dark tones of flesh and the subdued colors in the warm half-light of the harem.

——————————-

http://hoocher.com/Eugene_Delacroix/Eugene_Delacroix.htm

——————————-

Domingos Isabelinho says:

Mike: “Now, if Domingos were to say that art without symbolic/intellectual/emotional depth and complexity (or fine comics artwork in service of a mediocre story, as is virtually the entire oeuvre of Alex Toth) may still have other virtues, but just not be as good as it could be, that’d be a reasonable argument I’d heartily agree with.”

There must be some misunderstandings, then, because I agree with the above. The comics milieu favors work that is vapid or kitschy or childish over more adult accomplishments. I will acknowledge Toth’s technical skills the day people say clearly that _The Cage_ by Martin Vaughn-James of Fabrice Neaud’s _Journal_ is better than anything that Toth (or Hergé or Jack Kirby or Moebius) ever did.

———————————-

…confused “The Cage” with “The Spiral Cage,” Al Davison’s graphic novel about his suffering from spina bifida ( http://www.amazon.com/Spiral-Cage-Al-Davison/dp/0974056715 )…

…but finding a critique at http://thegreatgodpanisdead.blogspot.com/2009/12/cage-by-martin-vaughn-james.html , even a quick scroll down clearly shows Martin Vaughn-James’ book to be mind-bogglingly brilliant; certainly significantly above the level of anything Kirby (and I love Kirby) or Toth, Hergé, or Moebius ever did.

This is Art; working on many more levels, far more unsettlingly foreboding than Piranesi’s Carceri d’Invenzione or Ernst’s Une semaine de bonté…

Re Neaud, I’m not as “grabbed” at first look, but there’s also (looking at the pages in his interview at http://www.tcj.com/everything-i-do-i-do-at-an-increasing-risk-an-interview-with-fabrice-neaud/ ) clearly (even not trying to interpret the low-res French lettering) an attempt to express infinitely greater complexity of situations and emotional nuance.

(As I’d said back in the TCJ message board, I frequently disagree about the artists you damn as inconsequential, but for those you praise, your taste is impeccable.)

————————————–

Even if I prefer Watteau, comparing Fragonard with those other paintings is just ridiculous… If you don’t see that I can’t do anything for you…

—————————————

Heavens, I certainly agree that “comparing Fragonard with those other paintings is just ridiculous”; glad you feel the same.

—————————————-

Caro says:

…Even well-put-together genre fiction, which is rarely intellectually deep, is more than just well-phrased sentences (it often isn’t well-phrased at all, particularly, in fact). There are a lot of ways to think about “good writing,” but all of them pay attention to concept in some fashion, to things that can be analyzed, not just experienced – the story-arc conventions and emotional satisfactions of genre, the heightened sonority and aesthetic pleasures of poetry, the interweaving of plot and character in traditional novels and of narrative and structure in experimental novels, which provide intellectual and imaginative pleasures of varying types…

—————————————–

For the last couple of years (since a drastic income-drop necessitated my abandonment of buying comics) I’ve been reading a lot of classic-style murder mysteries from the local libraries. Re one favorite, a blurb on some Ngaio Marsh books quotes a NYT review: “She writes better than Christie!” Indeed she clearly does, in many ways; yet Christie’s most famed detectives, Poirot and Marple, are wonderfully vividly realized (becoming larger-than-life “real” as Sherlock Holmes), her plots and set-ups have a quality that “pops” more than Marsh’s more lifelike constructions. (Think theater compared to cinema verité.)

——————————————-

Matthias Wivel says:

…I just wanted to reiterate that an artist like Moebius — or to take somebody a little different, Crumb — express themselves through their images to an extent that goes beyond mere “craft” (however you want to define that). It’s imaginative, provocative and highly original and intrinsic to their success as artists…

——————————————-

Come to think of it, with all this talk of Orientalism, Moebius in his “Airtight Garage” stories shows the frequently clueless main protagonist Major Grubert (in the pith helmet and pencil-thin mustache of a British colonial officer) wandering about richly realized alien cultures. Clearly, imperialist colonialism is hardly being upheld here: http://pronountrouble2.files.wordpress.com/2010/01/airtight-garage-medium.jpg?w=449&h=600 , http://pronountrouble2.files.wordpress.com/2010/01/airtight-garage-medium.jpg?w=449&h=600 …

Heh! Gotta share; Hergé meets HPL: http://forbiddenplanet.co.uk/blog/wp-content/uploads/2010/11/fc2c5caa05b19f4d1e1aa508945cb4a2.jpg (From http://forbiddenplanet.co.uk/blog/2010/art-for-arts-sake/ )

Strangely enough I agree with everything being said.

I agree with Matthias’ appreciation of Crumb and Hergé (I love Crumb’s intricate telephone and electrical wiring, for instance; an iconological metaphor for how bad things have gone in capitalist society? I’m not that fond of Hergé’s neat buy scout world, or Moebius’ new age shenanigans, but I digress; Franquin has his moments too, I guess).

I agree with Noah above.

My problem is: Matthias deliberately forgets Crumb’s and Hergé’s wanting stories and problematic politics.

I agree with Ian when he says that we need more comics for children, but I can’t accept a comics canon overwhelmed by children’s comics.

I think that Noah overrates Asterix (national stereotypes are OK if done by Frenchmen?). Noah: “unapologetic elitism — has *no* (that’s “no”) traction, either in comics or basically in any of the arts at the moment.” That’s unfortunately true, the dumbing down is everywhere.

“[T]he sort of intellectuals [I’m] desperate to be associated with” are the only readers that could appreciate (if comics were seen as a normal art form which they aren’t) adult comics. Babymen and fanboys in the comics milieu proved over and over again that they’re incapable of supporting anything that wasn’t published during the Golden Age (the age of 12, of course).

Stereotypes in asterix are usually pretty jocularly presented as stereotypes, I think, and tend to be more jocular than demeaning. The French making fun of the British propensity to drink tea just doesn’t seem like anything to get especially exercised by to me.

There is some blackface iconography, which I wish there wasn’t. It’s a good deal less vicious/prevalent than in Tintin or Eisner or McCay, I think. Not that it isn’t embarrassing…but I didn’t say Asterix was perfect.

I should say though I’ve read selected volumes recently, there could be ones I haven’t looked at in a while that are worse. So far, though, when I’ve read Tintin to my son I tend to feel like I have to have some discussions about racism with him as we go. That’s much less the case reading Asterix.

Matthias says

I agree; I wouldn’t call those aspects craft either. I’d call craft things like brushwork and lines and shadow and other aspects of technical execution. I could paint with “celebratory vigor,” but what I came up with wouldn’t have craft.

But I think this discussion, which Matthias and I have on a recurring basis, is one where thinking about things in terms of the binary form/content with relation to the medium misleads. Matthias says “how most responsibly to treat the form/content issue when dealing with visual art” and I agree with the notion that we need to treat the form/content issue responsibly. I think where we go awry, though, is when we think of comics as composed of two things: words and pictures. Comics are composed of three things: words, pictures, and concepts — in the same way that pictures are composed of pictures and concepts and literature is composed of words and concepts.

The lesson of metafiction — although it is true for traditional fiction as well — is that EACH of those components has its own specific form and content. The mistake we make over and over is assuming that concepts are formless, that they do not have form of their own, a form specific to concept, independent of the material manifestation. Concepts have abstract form whereas words and pictures have concrete form, but “concept” is not a word for the “content” of material form. We map “concept” onto “content” and form onto the material expression of the content, but concept has form and content as well, and there is content to the materiality of art that is not equivalent to whatever concept is being conveyed.

So there are three places where form and content have to intersect and interweave. And there is “craft” appropriate to each of them: there is a craft to smithing words, a craft to making images, and a craft to manipulating and shaping conceptual content. Each craft takes study and attention and passion — each deserves vigour and beauty. And the presence of vigour and beauty in one doesn’t compensate for the lack of it in the others — especially for readers for whom one is more aesthetically powerful than the others.

What happens in the “not adult” comics that Domingos so often complains about is the “concept” part is given short shrift both in terms of its form and its content. Most commonly, most of the attention is put on the visuals, which makes the work incomplete. Comics can do without words but they cannot do without concepts. But what we often have is a strong emphasis on only the form and content of the visual imagery, which is at best 1/2 of what’s there to work with, and in most cases, 1/3.

Domingos is right — that’s not ever going to change as long as people are so quick to praise and even canonize work where the conceptual element hasn’t been allowed to develop fully, and it’s not going to change until people who read and create comics start paying more attention to concepts as concepts, rather than just being attentive to their medium-specific material manifestations.

Have to say I’m quite enjoying this thread about form/content/craft/concept/etc. Thank you all.

The writing in Asterix is pretty great, IMO. At least the translations are.

I’m somewhat uncomfortable with the idea that you can separate concepts out from their expressions, either in word or image, in a way that makes sense. Surely the point of the linguistic turn, or part of the point anyway, is to reject that kind of Platonist separation of the thing from its shadow?

I also disagree with the idea that work for children is less rich conceptually than work for adults. Alice in Wonderland or the Narnia books are tons more conceptually complex than Philip Roth or Milan Kundera, damn it, and nothing you say will convince me otherwise.

Yeah, this is where I get uncomfortable too, much as I agree with Caro in general. If one accepts this abstract division into three, concept would definitely be inherent in the qualities I describe in the art of Fragonard or Moebius.

As for “forgetting” problematic content, I do nothing of the kind, and while I agree that ethics and aesthetics cannot be separated entirely, one will almost invariably run into problems judging works of art, especially those of other times, if a rock solid criterion for quality is that they follow whatever precise, Platonic idea of what is ethically right one might hold at the time of judgment. To me, art just doesn’t work like that. Hergé and Crumb are pretty great artists despite — and in some ways even because of — their problematic ethics.

Maybe just to expand slightly…I don’t think you can have a drawing without conceptual content, or writing without conceptual content. I think that’s more clearly the case in writing (which is why the turn was linguistic), and Matthias’ constant irritation on the blog is that he feels that folks don’t acknowledge the conceptual content in, say, Crumb’s drawings in genesis.

I think what Domingos is arguing for (maybe?) is the idea that the concept of the drawing is part of the drawing too; since drawing/concept aren’t separable, if you draw a vile stereotype, you can’t say it’s drawn well — the stereotype is the drawing.

I guess to get around that you might try to argue that conceptual matter has multiple bits, just like the form does. For example, you could react to individual expression and emotion in Eisner’s drawing of Ebony White (which is conceptual and even ideological) and argue that that is a partial response to, or distancing from, the stereotype which is also conceptual and ideological. (I’m not sure I buy that for Ebony, really, but it’s the argument folks seem to make.)

“Hergé and Crumb are pretty great artists despite — and in some ways even because of — their problematic ethics.”

I wouldn’t call Herge or Crumb great myself, but I agree with your general point. I think Conrad is a great artist despite and in some ways because of his problematic ethics, for example.

That’s very funny, Noah, you want to agree with Matthias, but you can’t. The practical examples are conflicting with the theory :) (Conrad not-withstanding, but he wasn’t a comics artist.)

The reason why you are less offended by the black pirate in Astex than by Ebony is a mystery to me. There’s some political satire against Nixon and Le Pen and Jacques Chirac, but you said yourself that you don’t find political cartoons particularly complex or interesting (I forget your exact terms). There are some laughs, sure, Goscinny was a very funny man, but appart from that I fail to see what’s particularly interesting in seeing a bunch of “romans” being beaten regularly in formulaic manichean plots full of cardboard characters. So, what gives? Why is Asterix well written exactly?

As for national stereotypes why don’t you let the people being stereotyped to express their opinion? There was an important Portuguese immigration to France during the 60s. Maybe because of that there’s a Portuguese stereotype in Asterix and the least that I can say is that I don’t like it. Besides, that whole ridiculous story of the Gauls, etc… smells like Chauvinism to me…

Ugh! I feel that I’m losing my time with this.

We have gone from “art vs. craft” to “ethics vs. aesthetics.” Lets put it this way: great artists are never unfair to their characters. I refuse to call a manichaean racist work of art great art. Not because it is ethically wrong, but because it is aesthetically (how often do we forget what the word really means!) lazy and simplistic and childish.

Well, obviously the plot arcs aren’t consequential, but the verbal play and rhythms are very nicely done. I think the characterization of the individual gauls is funny and witty as well.

Asterix is certainly hyperbolically pro-French — though again, it seems more playful to me than an actual plan of action.

As I sort of said, I think the black pirate is easier to take than Ebony or the Imp in part because he’s just around a lot less.

Sorry to be wasting your time! I do enjoy hearing your take on these things, but can see how it might not be that much fun for you to talk about comics you don’t like that much.

I’m happy calling it something other than “more adult”! But I know you recognize varied levels of sophistication among different books, which I think is the point. Adults are just more likely to care than children, because the simple stuff is over-familiar.

But this topic, overall, the form/content thing, is one of the places where I feel like people tend to ignore the philosophical context of the linguistic turn in favor of decontextualized Derridean soundbites. The most fundamental concept in French theory, the one that everybody buys and works within or in response to with some variance in relative importance, is the semiotic distinction between the signifier and the signified. There are variations throughout French theory on that distinction, the most important being Saussure’s between langue and parole. There’s also enunciation and enunciated, noesis and noema in phenomenology. Derrida’s treatment of speech/writing maps onto it and advances a challenge to Saussure’s logic, to the relationship he articulates between langue and parole, but Derrida does not claim that speech and writing are ontologically equivalent. He absolutely accepts the fundamental gap articulated by structuralist semiotics — in fact, that gap is the kernel, the logical center, of his entire philosophical framework. You can’t have an empty signifier without a separation between the signifier and the signified, because the emptiness marks the radical nature of that separation, not its irrelevance.

The point of the later linguistic turn is not a rejection of their distinction, but of their discreteness. The traditional logic describing their separation is an inaccurate representation of their relationship. They are not binary; they are supplemental. But they are still not the same. A supplement to a thing is not the thing. The binary collapses, but difference remains.

So it’s not that you have a drawing without conceptual content, etc. It’s that the drawing is a sign with a signified, and both the sign and the signified, which are separate but not discrete, have form and content. There are many many names for the form of the signified, many ways of thinking about what it is like and how it works. Transformation grammarians call it “deep structure.” For Saussure it is the impersonal social system of language; for post-structuralists it is therefore an epiphenomenon of history. It doesn’t matter how it’s conceptualized — any way can be inspiring and meaningful. All that matters is that it isn’t ignored or taken for granted.

I think it is ignored when discussions about form/content fall into some simple “form can’t be separated from content” pattern — or when you get these facile observations about “drawing being thinking” and so forth. Those kinds of equivalences occlude the pluralities of form that are at play in all material, semiotic entities. We often talk about pluralities of content, tensions and multiple meanings and so forth. But form is also plural — always at least at the level of sign and signified, although not limited to that. That gap is mutable, but irreducable.

Fragonard’s paintings give perfectly good examples of this — they are not only visual representations of allegorical content, they are also conceptual interventions into that allegorical content. The conceptual interventions have life and meaning and significance — aesthetically and intellectually. Look at the opening section “From Allegory to Symbol” in Chapter 4 of Andrei’s excellent book on Fragonard if you want to see an example spelled out — a shift from Rococo to Romanticism that is not only aesthetic and visual but also conceptual, and therefore meaningful and useful in registers beyond the visual, including literary, philosophical and more broadly sociocultural.

But it doesn’t have to be something that has as much historical significance as Andrei claims for Fragonard. My usual example is the conceit in Midnight’s Children — “the promise of India’s democracy is like the potential of a thousand magical children, and the squandering of that promise is a crime perpetuated against that potential.” That’s just a simple, smart conceit. There is an abstract form to it, not fully independent of the representation, but malleable and permeable — there is Rushdie’s formulation; there is my summary statement, wherein it takes the form of the simile between democracy and children, the metonymy of individual and collective potential. But I could also represent it with venn diagrams; I could potentially represent it as allegory. There is a concept there, dependent on its manifestation but not identical to it. Conceptually Rushdie invokes our emotions about the potential of children, maps that emotion onto the potential of democracy — something people are vastly more cynical about — and uses that emotion to arouse a sense of sorrow and bitterness about the destruction of democratic potential. In the process Rushdie also constructs a metatexutal sense of “citizen subjectivity”, where we feel responsibility for the nascent democracy and recognize the human failures involved in exploiting it. The system of identifications and responsibilities are subversive throughout.

They work as concepts; they transfer out of the book. Rushdie’s network of relationships among shared concepts — children, democracy, potential, crime — is very sophisticated ON ITS OWN, even in summary, regardless of the specific form it takes in the novel. It would be equally conceptually satisfying if he’d written it as an essay, although it would not be equally emotionally affecting or perhaps aesthetically satisfying (depending on your aesthetic feelings about non-fiction.)

The work gives the concepts a life of their own. Great art is pregnant with meaning. But the mother is not the child.

He could have written a book that was very emotionally and aesthetically satisfying and affecting without a concept as complex and carefully constructed as the one he used. BUT HE DIDN’T. And his book is the richer for it. That conceit is what knocks it from a well-crafted ordinary novel to the book that won the Booker of the Booker’s for the ’80s.

He did not get there by thinking about the form of the novel and only the form of the novel. He didn’t get there just by writing draft after draft, although that was part of the process. He got there by thinking imaginatively about those concepts. It is surely dialectical — the treatment shaped it into something more powerful than it probably was at the idea stage. But there was an idea stage, and it was every bit as ambitious and smart on its own as the making-the-book stage. It’s just not a foreign concept in advanced writing to recognize that the author manipulates both the signifier and the signified, independently and together.

If you just understand concepts as “inherent in” the material crafting of form, you end up with concepts that are bound to that form, just stated, their problematics suggested rather than explored (as in Rushdie) or even exploded (as in Fragonard). And suggesting a problematic concept (as Eisner does) is insufficient to make a representation of that problematic into Art. The artist has to do something smart with it.

Ah that makes sense…except for your unaccountable enthusiasm for Rushdie, whose democracy/children parallel strikes me as intellectual kitsch. But mileage differs in this as in all things, I suppose.

You should read the book! It has all kinds of exotic crimes and body horror (the children get their reproductive organs ripped out) and this really complex section weaving Islam/Hinduism into Pakistan/India that pulls this nice Derridean supplemental collapse as a challenge to the political binary.

Point being, there’s much much more in the book than my pithy encapsulation here — blame the kitschiness of it on me. :)

Glad it makes sense, though.

Actually…I sort of wonder if the irritation I have with pomo fiction like Rushdie has something to do with the sign/signified distinction, and the way that it often becomes so schematic in post-Borges writers. The conceit is so pleased with its own cleverness and aptness as conceit; the delineation of the conceitness is too neat.

I think Kafka maybe is somebody for whom the sign and the signified don’t separate out as neatly, and who is a (vastly, in my view) greater artist for it. For Rushdie, the children = democracy; sign/signified. It’s controlled as you say; he’s shaping the conceptual material, and you can feel him doing it, which ends up feeling kind of smug. For Kafka, though, the cockroach doesn’t mean one thing; in fact it’s failure to mean one thing is part of what it means. Not that there isn’t sign/signified in Kafka, or that there isn’t control, but the boundaries them aren’t as schematic; he deliberately blurs them. I find that much more conceptually and aesthetically compelling.

Sure, but that’s why I said the important thing isn’t HOW it’s conceptualized but that it isn’t ignored. Kafka’s conceptual material is still sophisticated on its own terms, it still has a form. I was giving particularly stark examples to make sure the point I was trying to make came across and effectively responded to the question you asked about the linguistic turn, but the idea of shaping the concept doesn’t have to be approached from that standpoint.

The problem I have is when an artist tries to assert that “craft” is sufficient, or the next step, which is that attention to craft will automatically produce sophisticated concepts. I don’t buy that. It might not matter in visual art — I’m not going to say that non-conceptual art is bad art or not art at all; I do not have a horse in that race.

But in narrative I do — narrative needs a concept. Books are semiotic objects, and comics are books. The signified is there; it’s just a question of what to do with it.

Saussure is schematic, but the distinction between sign and signified is not always schematic. It’s not really at all schematic in phenomenology. But the distinction still exists…

Noah –

“Domingos is pretty upfront about his interests and standards. He’s also upfront (and he’s right) that his viewpoint — basically unapologetic elitism — has *no* (that’s “no”) traction, either in comics or basically in any of the arts at the moment. Given that, it’s hard for me to understand why he provokes such vitriol.”

Because it’s always presented as absolute fact rather than as subjective opinion? Because it’s generally conveyed in as curtly antagonistic a fashion as possible? Or because its a kind of pathological anti-popularism that’s an inherently confrontational, divisive, joyless way of looking at the world. Take your pick.

I honestly have absolutely no problem with Domingos not liking Moebius or Asterix or Astro Boy or anything else. I have no problem with him explaining why he doesn’t like those things or why he thinks other people are wrong about them. Quite the contrary in fact. But “that sucks, if you read it you’re a moron” isn’t much basis for a discussion.

“On the other hand, there really aren’t enough people who like Tsuge”

You really have to blame Tsuge for that. He’s the only thing stopping most of his own work being published in English as far as I can tell. Good as they are, it’s kind of hard to enthuse people about three out of print short stories, at least one of which is prohibitively expensive to get hold of.

That aside, why does the promotion of X have to rest on the denigration of Y and Z? If X is perfection incarnate, does it necessarily follow that Y and Z are entirely without value? I don’t buy it.

“Moreover, having *somebody* whose skeptical of certain sacred cows seems like its worthwhile too”

Scepticism is great. I love scepticism. Iconoclasm for the sake of iconoclasm, though, is tedious and adolescent.

“The writing in Asterix is pretty great, IMO. At least the translations are.”

The ones written by Goscinny, yes. The later ones with Uderzo flying solo mark a pretty steep decline in writing quality. I’d read up to Asterix In Belgium and leave it there if I were you.

“since drawing/concept aren’t separable, if you draw a vile stereotype, you can’t say it’s drawn well — the stereotype is the drawing”

So…can an evil person not be good looking? Can a poorly conceived house not be well constructed? Can a crappy car not have beautiful lines?

Semantics aside, I get the argument being made but it feels kind of reminiscent of totalitarian (political or religious) calls to censorship…the idea that *any* ideological taint is sufficient to wipe out whatever other qualities a work might have is a fairly poisonous one I would have thought.

Domingos –

“I agree with Ian when he says that we need more comics for children, but I can’t accept a comics canon overwhelmed by children’s comics.”

I don’t get what people like about Kirby. I’ve tried and I really can’t see it. But I don’t let the fact that he makes every list of comic artist “greats” stop me from enjoying the stuff I do like. Why should what other people consider canonical impact on your own reading habits, or your appreciation of the texts you do choose to read? Why should it stop you trying to get other people interested in the stuff you like? Would taking away other people’s juvenile toys really mean a mass surge towards the serious, “adult” work you want to be venerated or would people just go do something else entirely?

I’ve read some Rushdie. I don’t think you did him a disservice.

I agree with you in general, though I might put it somewhat differently? I think there is always conceptual material; there’s always a signified. The craft can itself be part of that signified (as it is in Britney or Steely Dan in different ways and to some extent.)

But that doesn’t mean that well-accomplished craft is necessarily well-accomplished concept. That is, just because the craft is good, and just because craft is conceptual too, doesn’t mean that it has to be seen as adequate conceptually (though it could be.)

Steely Dan, as long as I’m talking about them — they’re totally a reaction to, or in conversation with, the idea of rock as authentic roots music. They’re really almost satirizing that idea. And they do that by craft; they take roots music and they put it into these really careful, polished arrangements. So the craft has a conceptual meaning.

Does that make sense?

“That aside, why does the promotion of X have to rest on the denigration of Y and Z? If X is perfection incarnate, does it necessarily follow that Y and Z are entirely without value? I don’t buy it.

Doesn’t have to, but practically one tends to draw lines.

And, oh yeah, the Uderzo written Asterixes are terrible.

Ian asked: “Why should what other people consider canonical impact on your own reading habits”?

For me at least, the answer seems to be because the type of work I most like to read is exceedingly rare. Although not entirely, this is at least in part due to its being underappreciated by the consensus community, which tends to like things more informed by comics history than by art in a broader sense, especially literature. There’s this sliding scale of availability — there are a ton of comics influenced by comics history and DIY autobiography, there are a less-but-still-significant quantity of comics primarily influenced by visual art, and there’s a pretty limited quantity of comics influenced by literature and philosophy. Discussion of the books corresponds to availability, so it’s also harder to find the books that do exist that are influenced by literature and philosophy.

Hence, my reading habits are affected. I can either not read comics or I can plod through comics that aren’t really what I want to read in the hopes that maybe there’ll be one that actually is something I’m interested in. I do the latter, but it’s tiresome. And it’s really REALLY easy to say “why the fuck am I paying attention to comics when there’s this whole culture stacked against the things that matter to me?”

Of course the answer to that is because it’s worth a little tedium to uncover books like “Fate of the Artist” or “W the Whore” or “Faune” or Jason Overby’s “Michelle.” But it doesn’t change the fact that if those books were the first thing people thought of when they thought of comics, rather than Kirby and Herge and Ware et al., my reading habits would look a hell of a lot different, because what was available to me would look different too.

———————

Domingos Isabelinho says:

…There was an important Portuguese immigration to France during the 60s. Maybe because of that there’s a Portuguese stereotype in Asterix and the least that I can say is that I don’t like it. Besides, that whole ridiculous story of the Gauls, etc… smells like Chauvinism to me…

Ugh! I feel that I’m losing my time with this.

———————-

Heh! You might relate to critic John Simon’s saying that in past arguments he’d been out of his depth, but “here, I’m out of my shallowness…”

Noah –

“Doesn’t have to, but practically one tends to draw lines.”

Absolutely. It’s just that most people have a grey area in between those lines. That’s the area where all the interesting discussion takes place.

Caro –

I understand what you’re saying and I understand how frustrating that must be. I’m not sure how it corresponds to canon exactly though. Surely, something doesn’t have to be popularly acknowledged as a masterpiece in order to get published?

And it’s not as though every time somebody picks up a genre comic – or a middlebrow indie comic for that matter – a literary gem gets pulped as a reprisal.

“Of course the answer to that is because it’s worth a little tedium to uncover books like “Fate of the Artist” or “W the Whore” or “Faune” or Jason Overby’s “Michelle.” But it doesn’t change the fact that if those books were the first thing people thought of when they thought of comics, rather than Kirby and Herge and Ware et al., my reading habits would look a hell of a lot different, because what was available to me would look different too.”

I can’t help thinking that if those sorts of books were the first thing people thought of when they thought of comics, there probably wouldn’t be any more of them – just a lot less people reading comics overall and a lot fewer comic publishers. I don’t say that because I think those are bad books (I’ve only read one of them but I liked it a lot – I don’t doubt the others are worthwhile too) but because I think the potential market for those books is just pretty small.

That might change and I hope it will – I think more diversity would be very healthy for the medium. But I would have thought, in a commercial art form, that the lowbrow supports the middlebrow supports the highbrow. The lower levels can survive without the upper but not the reverse. Popular cinema supports arthouse cinema. The airport novel supports great literature. Tsuge would probably never have found a significant readership if Shirato’s ninja comics hadn’t given him a home and an audience. I’m just not so sure you can (or should) entirely divorce the stuff you like from the stuff you don’t.

Ian,art forms work in different ways, and it’s not always true that tons of genre work cultivate high art work, or what have you. For example, visual art is pretty divorced from commercial art.

Also…caro’s looking for a particular kind of high art. She’s not talking about genre at all; she’s talking about the space for comics that value writing, rather than memoir or comics that look to visual art. I think it’s reasonable to see that as something that could be, or is, affected by critical discussions and critical interests within comics.

“it’s not always true that tons of genre work cultivate high art work”

I don’t think they cultivate it so much as they support it logistically and economically. And I don’t think the lowbrow supports the highbrow – I think it supports the middle, which in turn supports the high. It seems to me that its that mid-level – as stodgily respectable as you might think it is – that needs to expand in order for the art comic to prosper.

“For example, visual art is pretty divorced from commercial art”

Yes – I agree. I think I did note that I was talking specifically about commercial media (and I’d argue that – as with the rest of the publishing world – comics belong firmly in that category).

“She’s not talking about genre at all; she’s talking about the space for comics that value writing, rather than memoir or comics that look to visual art. I think it’s reasonable to see that as something that could be, or is, affected by critical discussions and critical interests within comics.”

But could the sort of art comics she wants to read exist without the undergrounds and their successors? And would the undergrounds have existed without Harvey Kurtzman and Walt Disney and so on? I feel like comics is too young and small and incestuous, too interlinked, to really be able to separate off little bits of it to consider in splendid isolation like that.

Here’s where I draw the line. Have a nice day…

“I feel like comics is too young and small and incestuous”

That’s Caro’s point!

Art doesn’t happen in a vacuum (or a single consciousness); it happens in a culture. Canon, when it refers as it does here to a popular, communal consensus, is just the zeitgeist of that culture.

If nobody pays attention to a type of work, only a very small amount of that work will even get produced in the first place. If works get a lot of attention and acclaim, aspects of those works will find their way into other works — more works like the ones people pay attention to will get created. So what’s “in the canon” (or even just in the conversation) influences what gets made, not just what gets published.