Eddie Campbell had a long comment in which he talked about Persepolis, Habibi, the relationship between art and writing, and other matters. It seemed a shame to leave it at the end of the comment thread, so I thought I’d highlight it here. (I’ve tweaked formatting on a couple of links, but otherwise it’s unedited.)

(in response to Mike)

Matthias wrote, in his opening paragraph : “one is perhaps fooled into believing that the form is finally receiving its due, that we have moved beyond the facile.. “story vs. drawing” discussions of yesteryear.”

And then you entered into a “story vs drawing discussion”.

Such a discussion belongs to the arena of comic books where the convention is that different tasks are assigned to different practitioners (you show that you still dwell in this arena when you refer to Ditko and Kirby). And even if they are not so assigned, this consideration of separateness is now ingrained. An aficionado of the comic books follows his favourite artist from one job to the next, hoping that he will occasionally be teamed with a partner worthy of him.

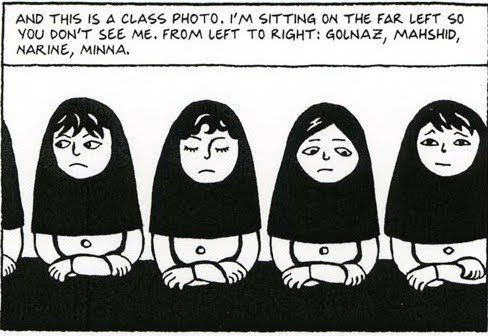

An essential demand of the newer kind of comics under discussion, in which a unified whole is presumed, is that we find a more apt way of talking about them. Satrapi’s Persepolis, when it opens, is the first person narrative of a ten year old girl. The drawing is perfectly right for the story; it expresses the world view of a ten year old girl living anywhere. Characters are simplified in a way that is charmingly naive and perspective is nearly non-existent. Whether Satrapi is capable of a different kind of drawing is not relevant to a discussion of the book. The artist is not a musician being hired by a symphony orchestra that expects her to be able to play the whole classical repertoire. She is giving us a record of her personal experience. She has a natural grasp of what is important in telling a story, which unfolds with simplicity. By the end of the first book we are surprised by how much information we have taken in, as we weren’t aware of taking it in. We thought we were listening to a child talking.

The authentic voice of the original can be appreciated by comparing it with the more professionally knowing treatment of the material in the animated movie parts of which are

excruciatingly embarrassing.The professionals who worked on it will go onto their next gig and we may hope they will be teamed with material more suited to their outlook.

As to Habibi, Matthias shows that there is nothing in Thompson’s art that is not in the overall meaning of the book. To praise the art separately is the reflex of the critic who has unconsciously recognized the ‘generosity of intent’ that is all over the work and doesn’t want to end on a rude rebuke. That intent is as much the CONtent as anything in the book that appears to be about the Arabian world. Looking at it again two months after I first opened the work, what I see is a cartoon romantic fantasy. I’m incredulous that it has inspired so much argument, or that in a medium that produces a mountain of crap over and over every year anybody could think this is among the “worst” that comics has to offer in 2011.

As always, the criticism against Thompson is that he didn’t make the book that thinking folk wanted him to make. I recall that the title of the TCj review of Blankets in 2003 (2004?-Tcj is never timely) consisted of those words more or less (‘Why Blankets isn’t the book… ?) Here it’s that Habibi is not a complex poem about modern life as reflected in the travails of the middle east, and also he didn’t draw it more in the manner of Blutch.

I remain however dubious about the remark that there is an implicit assertion that the book is more than broad melodrama. I thought that Nadim’s observation that there was more of Disney’s Nights than Burton’s was apt. And the ecological message isn’t more profound than ‘we need to look after the world because it’s where we live’.

While the lavish attention to tangential information raised hope of profundity, some critics have had trouble with him breaking up the linearity of the story unnecessarily. But I see that as just a Tarantino thing. A normal person nowadays takes in so many pre-digested stories (still on holiday, I think I inadvertently watched four movies yesterday) that rearranging the normal running order of events becomes a way of pumping some fizz into the flat drink. There can’t be anybody who doesn’t know how stories go. Sometimes I come into a movie ten minutes late just to make it more interesting. I tried it with Inception yesterday and it still didn’t work. We are a society that is weary with it all. We get more complete stories daily than ever before in history. We shuffle the pack to stave off boredom. Lists. the Months of the calendar of pregnancy, the names of the rooms in the palace, the planets, the nights of Sheherezade, the walk-ons of the Cheshire cat, the ninjas of Frank Miller, the Goddess Bahuchara Mata. Witty juxtapostions: the prophet at the farthest limit of human understanding plays out over the slave putting a spanner in the works in the Rube-Goldbergian plumbing inside the heart of Wanatolia. it’s a play-bauble being turned around and viewed from every possible angle. It’s not the ink line that is the virtuoso show, but the cartoon invention, the prodigious flow of ideas. The ink line serves the demands of clarity, of the ‘control’ that has been discussed above, and it speeds in comparison to Blutch’s because that also is demanded of it. It is liquid, and the ideas run as though out of a tap that has been left on, spilling out the supply of water necessary to quench the thirst of a careening dash through this Arabian fantasy.

And as with Satrapi, that is why Thompson’s drawing is inseparable form everything else in the book. There is certainly much that I find odd in it, including a coy Middle American sense of humour, as in the farting little man in the palace. Isn’t farting viewed differently in Arabia? And the convoluted treatment of sex in Thompson’s work will certainly one day attract a separate study.

The entire roundtable on Habibi and Orientalism is here.

Thanks Eddie, for this perceptive critique of Habibi (and of Persepolis), and for turning to one of the points of the original essay that got lost a little in the heat of discussing other interesting issues.

A few short comments:

– The ‘control’ I see in Thompson’s line has nothing to do with clarity; to me, it’s showy and somewhat aesthetically didactic in its deftly swung layering of brushwork, far from the gush of creativity you see in it. I agree with your description of the book as a play bauble, a catalogue of ideas, and as I wrote I think Thompson should be commended for attempting what he does, but to me his linework and his stereotyping impairs it, if anything.

– No, I don’t think the book would have benefited from Thompson imitating Blutch more. He already does so too much, and my comparison between the two cartoonists was in part made to demonstrate the problems this causes. That being said, Habibi looks considerably less like Blutch than did Blankets and is the better book for it. Thompson deserves credit for this.

– On Habibi being or not being more than broad melodrama: to me it isn’t when one considers what seems its conscious conceptualization, but as I wrote at the end of the essay, and certainly didn’t develop enough, I find the sexual tension, what seems the author’s unhealthy obsession with rape and subjugation, and the way they’re given form through this uncomfortably and almost demonstratively controlled cartooning, to be quite fascinating beyond the narrative and characters themselves — a deeper, probably mostly unconscious layer of signification that I would be interested to see Thompson develop further. Now, on his blog he recently mentioned that one of the projects he is currently considering is on sex. I’m not sure what to think about this — it certainly risk going catastrophically wrong — but if handled right, it might make for a tremendously interesting comic.

Did you have any thoughts on my post about Thompson’s controlled cartooning and sadism, Matthias? Feasible? Nutty? Not worth thinking about? Some combination thereof?

What on earth does “aesthetically didactic” mean?

It’s not that confusing, is it? He means it’s diagrammatic, basically, though the connotations are slightly different because that’s how language works. No need to be snarky about it.

“Aesthetically didactic” means, basically, “diagrammatic”? I’m calling bullshit.

Well, it was a way of describing what I see: lines that dictate where I should look and what I should think; lines that are demonstratively wrought, asserting their elegance. Sorry if it sounds like bullshit.

Sorry Noah, I hadn’t read your piece, but now I have. I basically agree with it and, as indicated in my previous comment, do think that the control and deliberation Thompson brings to his work creates a palpable frisson with the more repressed-seeming aspects of the book.

The lines are asserting their elegance because they’re elegant. They’re dictating where you should look because that’s what lines do. The bit about them dictating what you should think is entirely your projection.

I’m afraid that you’ve disqualified yourself from these sorts of observations. You claimed in your review that Thompson “uses the same lines to delineate the curve of a sand dune and bodily effluvium.” And in the accompanying illustrations, these lines look nothing alike except that they’re black.

You probably feel that you’re entitled to your opinion about those lines, and this is the mistake made by a lot of intelligent people who are involved in criticism but should not be. Only the expressive aspect of criticism, the part in which you translate your impressions into words, requires intelligence. If those impressions are faulty, if, like you, you’re seeing things that are not there and not seeing things that are, then intelligence is of no use. You end up with opinions that don’t attach to observable reality. Contemporary criticism has attempted to bypass such attachments for complicated political reasons, but the egalitarianism that its practitioners were hoping for never materialized. Instead they got a sheltered workshop.

Which is pretty much all you need to know about the Slow-Rolling Orientalism project as a whole. Noah has invited me to respond to this at length, but the shabby treatment that Habibi has been receiving here week after week is a political exercise expressed as a critical one, not a critical exercise itself, and I’m thus reluctant to get further involved. I’ve only contributed a couple of pieces to HU, but I thought it would make a stronger statement to demand that Noah remove them. A fellow artist talked me out of that. Instead, in the spirit of the the truth that the best revenge is living well, we’re going to continue making our work in hopes that one day it inspires an equally bilious and drawn-out reaction at Hooded Utilitarian. Cheers!

Matthias rather likes Habibi, so your hostility to him here seems odd…especially because he’s also argued against the sort of ideological assessments which you’re denigrating.

I mean, do you agree with Eddie’s comments? His take is mostly positive, right? And of course Thompson made his own case in the interview he had with Nadim. I’m certainly not against including positive assessments of Habibi. As I’ve said before, I wish you were willing to talk more about why you like it. I don’t really see how refusing to do that helps Thompson or rebukes me — though I like your art, so I’m of course always happy to hear that you’re working on that.

Similarly, I’m glad you’re not planning to remove your pieces. Give my thanks to the artist who convinced you not to.

OK, fair enough re: the example about “the same lines” — I definitely put that inaccurately, and it’s actually been bothering me for a few days already. What I meant to say was that they carry the same kind of brushed elegance (with the effluvia adding in some toothbrushy splatter), the kind that calls attention to itself as brushstroke rather than what it is meant to signify, and which especially in the case of the shit/vomit is inappropriate.

Since I’ve apparently “disqualified myself” I guess you need no further argument from this rube, but what I wrote is indeed “my projection” — what else could it be? That’s what art calls upon and all I can do is try to formulate it as well as I can. To me, those lines are simply not elegant (Blutch is; that piece of Japanese calligraphy Noah posted is), but rather overdetermined and demonstrative. They don’t just tell me where to look, but *how to look in a way that I find ostentatious and, well, stale. You disagree, fine — but then let’s have your words on how they’re something else, instead of this petulant griping.

I should add that it seems to me that you’re just as guilty of seeing things as I may be, perpetuating as you do one of the most common, yet entirely bogus complaints about HU, namely that it’s some monolithic entity bent on tearing down everything you and others hold dear. Nothing could be further from the truth — this is a very pluralistic forum that may well exhibit strong biases against received wisdom, but allows for plenty of dissent.

Speaking for myself, I can say that most of the time I disagree pretty strongly with several of the other writers and commenters here — and my piece took direct issue with several of them, but you seem to have missed that.

I should further note that I’ve found myself agreeing with many of your comments on art and aesthetics, comments which were formulated against other writers here on the site. This is a pretty accommodating place, actually, when you look beyond your own knee jerking.

In case people are interested, Jason Michelitch (who writes for HU whenever I can convince him to do so) has a nice piece at comics alliance about Habibi. I wish I’d been able to get him to write it for us, but I guess I’m just not destined to get anyone to write a positive piece about the book.

Laura Hudson’s essay about Finder in that same post is also excellent.

Thanks for the link; unfortunately, that Michelitch piece is as breezily insubstantial as a TV station critic’s movie review.

Is the way to come up with a mostly-positive review of Habibi to focus on its pluses, then utter meaningless, frothy stuff like “Habibi is not a perfect book — and how boring it would be if it were!”, and lightly touch on its troubling aspects, carefully taking no sides?

Hi Mike,

I took no sides because I don’t know which side I come down on. It may seem inherently contradictory, but one of the reasons I like Habibi so much is that I have no idea how much I like Habibi. Thompson crafted a clear, elegant narrative laden down with so many purposeful and perverse roadblocks to simple enjoyment that the frisson of friction I get from moving through the book is more exciting than 99% of other comics.

I’m sorry you thought the piece was breezily insubstantial. I didn’t really see the forum of an entry in a mainstream Best of Year list as the spot to delve into pages of analysis. But that’s why I pointedly mention the inability of a piece that short to sufficiently unpack Habibi, and even include links to two different Hooded Utilitarian pieces in the hopes that people would take the cue to read more in-depth discussion of the book than I could provide in my limited space. I guess I’m being a little thin-skinned here, but when was the last time a TV Station Movie Critic held up a copy of “Film Quarterly” and suggested the audience pick it up and read further about the movie under discussion?

Hi Noah,

It’s been a busy year, but I always like writing for HU. It might take some time, but maybe I can work up a longer, trending-positive Habibi piece (though Eddie Campbell’s spotlighted comments are way better than anything I can write) – if not that, I’ll pester you with some kind of dumb idea for a post soon.

Thanks for the link!

[apologies if this posts a bunch of times – something is happening with my browser and the CAPTCHA system…]

Agh; sorry about the spam filter Jason. And yes, I’d love a positive Habibi post…or something else if it occurs to you!

The filter may have been confused by the fact that I am, in fact, made of Spam.

Considering the mine-strewn subject matter that Thompson chose to navigate, the question is how could one not bring up the politics inherent in the storyline. I mean, from the Western perspective if there’s one area where politics should be considered this is it, isn’t it?

I get that one should run away from academia as far as possible, but that doesn’t mean all politics should be sundered from criticism. That’s just substituting one knee-jerk POV with another.

I don’t disagree with that. I hope I didn’t give you that impression.

Steven:

“I get that one should run away from academia as far as possible”

Why? If you don’t mind me asking. Most of the best comics criticism came from academia.

It’s trendy to be anti-academic. Sigh.

It’s trendy to be anti-academic. Sigh.

It’s not just that. For the last forty years at the picnic of the arts and humanities, academics have been the ants. Leaving aside the increasing systemic failures of college education as a whole described by Jane Jacobs and others, additionally leaving aside the fetid interpersonal culture and political monoculture of academia to which just about anyone ever involved can attest, it tends to revolve around an in-group of indoctrinated adherents given to name-dropping, hair-splitting analysis conducted in a mode that is wholly alien to both art and humanity.

As demonstrated by the fine art world, as academics gain power they make life increasingly impossible for creators who don’t make academic work. The vital phase of every movement of art for the last 150 years took place while the academics of the time were either paying no attention to them or speaking out against them. This is not an accident. Since then academicism has become, by definition, art executed according to a script. Academic criticism judges work based a checklist of vaunted, describable virtues, instead of the intuitive basis where aesthetic pleasure takes place. Lastly, academics and the academically minded who spend enough time assuming a universe in which nothing is inherently true, beautiful, or good finally become unable to make clear discernments about what is false, ugly, and evil, and they act accordingly.

There’s lots of thoughtful, beautiful academic criticism that is itself an aesthetic pleasure, at least according to my intuition (and the other parts of my skull, such as they are). On the other hand, there’s lots of academic work that’s boring and stupid (again, per intuition, other bits of skull, etc.) The relation between academia and the arts is pretty complicated; sometimes it’s horrible (as with contemporary poetry), sometimes less so (as with people like Godard.)

I don’t personally, as an artist or critic or audience or whatever, want to separate out reason or critical functions from intuition in appreciating or thinking about art, or even in creating it. I don’t think brains are split up like that, myself — or anyway, my consciousness isn’t.

Caro’ll have a less wishy-washy response, maybe.

In other words: academics are damned if they are Manichean and are damned if they’re not.

“I don’t disagree with that. I hope I didn’t give you that impression.”

No no no. Didn’t mean you. I guess I didn’t make it clear enough that everything I said was in reference to Franklin’s first post.

And I should’ve further clarified my statement by instead saying that one should stay away from the bad side of academia. Didn’t mean to sound like I was replacing one kneejerk response with another. Of course not all of academia is bad. Like Noah just said, the point is not to characterize everything with a single brush stroke.

—————————–

Jason Michelitch says:

I took no sides because I don’t know which side I come down on. It may seem inherently contradictory, but one of the reasons I like Habibi so much is that I have no idea how much I like Habibi. Thompson crafted a clear, elegant narrative laden down with so many purposeful and perverse roadblocks to simple enjoyment that the frisson of friction I get from moving through the book is more exciting than 99% of other comics.

——————————–

That’s an odd, but fascinatingly defensible approach. (Rather like Eddie Campbell’s astonishing “Sometimes I come into a movie ten minutes late just to make it more interesting” tactic.)

———————————

I’m sorry you thought the piece was breezily insubstantial. I didn’t really see the forum of an entry in a mainstream Best of Year list as the spot to delve into pages of analysis.

———————————

When Noah suggested it as a “positive piece about the book” that he wished could have appeared in HU as a differing viewpoint, it unfortunately couldn’t help appearing lightweight when set up in opposition to everything else ripping up on Habibi that had appeared/been cited here.

Apologies; it certainly deserved to be considered for what it was intended to be, rather than “put in the ring” with works of a whole different “weight class.”

———————————-

I guess I’m being a little thin-skinned here, but when was the last time a TV Station Movie Critic held up a copy of “Film Quarterly” and suggested the audience pick it up and read further about the movie under discussion?

———————————–

Rather than oversensitively thin-skinned, you’re making a perfectly sound point, in a calm and polite fashion. Mea culpa…

————————————

Domingos Isabelinho says:

In other words: academics are damned if they are Manichean and are damned if they’re not.

————————————

So, the only choice is between the Mr. A-type extreme of Manicheanism and the other of (as Franklin said of Academics) “assuming a universe in which nothing is inherently true, beautiful, or good”?

I think Domingos is pointing out that Franklin dinged academics for evaluating art according to criteria and then dinged them for not being able to make distinctions.

Though presumably Franklin would say academics make the wrong distinctions and are unable to make the right ones….

Franklin, as I said, we’re probably more on the same page than you might think. I concur with Domingos and Noah that the logic in your piece is a bit fuzzy, but I agree with your description of academic approaches to art as having become increasingly problematic, and agree that modernism has come to occupy a bizarre — compelling yet suspect — place in contemporary curricula.

Regarding academia and the humanities, I further agree that it has become largely unsuited for the formulation of resonant criticism. This piece by Jeffrey Kurtzman on the state of the humanities compellingly identifies several key problems.

Uck…just read the first bit of that Kurtzman thing, but…you like that Matthias? The prose is unstylish academic boilerplate, and the insights seem exceedingly pedestrian. “Oooh…Einstein showed us that everything is relative.” I don’t know; that really just seems like lazy half-assed drivel to me. And then he starts droning on about the dangers of theories; please. As if pragmatism and empiricism have no theoretical roots, or as if rampant pragmatism has worked so well when it’s been tried (by, for example, our current President.)

I guess I’ll try to wade through the rest, but Ben Saunders’ book seems like a much more thoughtful exploration of the problems with modernity…not least because he’s actually a good writer.

…and reading on we’ve got boilerplate anti-PC finger-wagging…

…and a standard simplistic take on the reasons people do art. “their age-old appeal to human beings as a way of experiencing, expressing and understanding a wide range of human emotions and interrelationships.” I don’t think that’s what John Donne thought he was doing when he wrote sonnets praising God. I don’t think it was what Brecht was doing when he wrote plays in an effort to bring about the revolution. I don’t think it’s what the creators of Friday the 13th were doing either, exactly. Is he even thinking about what he’s saying? Sounds like regurgitated talking points.

Hah! There he goes sneering at comic books. Guess I should have seen that coming…. “it is an unreal fallacy to think that comic book literature can teach us as much about the human condition as Shakespeare, or that Madonna and MTV can teach us as much as Mozart.” I wonder what objective criteria he’s using to obtain those insights? Did Einstein leave an equation?

“. Theories of literature are inevitably less real and less true than experience with the literature itself, yet theory has supplanted the very substance on which it is supposed to be based.”

What do you do when the literature is theory, though, I wonder? I just read War and Peace, and a lot of it is extended theoretical discourse about history. The theory seems to be the point, in a lot of ways. I don’t think the theory is all that interesting, personally, and prefer the social satire (as opposed to the paens to domestic bliss)…but obviously Tolstoy thought the theory and the literature weren’t separable. In fact, he goes to some pains to argue that human experience isn’t reliable, and that human empirical experience of, for example, free will is nonsense, because we’re all part of the divine plan. So does Kurtzman know what Tolstoy was doing better than Tolstoy does? Do the theoretical parts of War and Peace not count; should we just skip them to get to the human interaction parts? How is that honoring Tolstoy exactly?

All right, that’s enough. He’s made a very good argument against academia, mainly by epitomizing the sloppy thinking, self-satisfaction, finger-wagging, and general ignorance that is all too prevalent in the academy (and outside it too, to be fair.) So kudos to him for that, I guess.

I’m not a scholar and I’ve never been one. I don’t know what’s going on in Academia and, frankly, I don’t care (power struggles are everywhere, so, how could academia be an exception?). I’m against the overrating of most “popular culture” and whatnot (I also understand that many times there’s no explicit, at least, value judgments of trash in cultural studies)… But… this I know (and forgive me for the namedropping): when there are comics scholars like Charles Hatfield, Donald Ault, Joseph Witek, Ann Miller, Pascal Lefèvre, Peter Sattler, Craig Fischer, Jan Baetens, David Kunzle, Thierry Groensteen, Bart Beaty, Ole Frahm, etc… etc… who can deny that the best comics criticism is done in academia?

Sorry Matthias…that essay made me really cranky.

I do kind of wonder though…so many artists have major ideological axes to grind, one way or the other. A lot of Shakespeare’s plays are explicit political works in favor of the divine right of kings, and were surely perceived as such at the time. They also have quite conscious Christian content (as in the resurrection in the Winter’s Tale.) I just don’t get the point of turning all artists of every time into boring humanists whose main goal is to make us consume our human interactions with more rational relish.

Artists at different times and in different places have and had really different goals and very different intellectual commitments. Recognizing that — pointing out that Kipling’s an imperialist or that Dickens was invested in Victorian ideas of womanhood or that Shakespeare thinks kings are awesome — isn’t some sort of cultural dross you have to separate from the pure humanism of their art. It’s part of the art; it’s one of the things you respond to and think about in understanding what they’re doing. It doesn’t have to be the only thing, and it certainly doesn’t mean that you have to dislike the artists (Kipling and Shakespeare and Dickens are all great.) But all art occurs in a cultural context. Trying to erase that just makes your criticism boring.

Holy christ, just read some more. This is a gem.

“This understanding of others also means understanding the emotional orientations and commitments of others, what in contemporary business vocabulary is called emotional intelligence.”

He is actually arguing that the humanities need to take their cues from the utterly debased rhetoric of management gurus.

I better stop with that.

Come on Noah, were you reading that while on the toilet? Your criticisms mostly set up straw men Kurtzman never erected. He doesn’t say anywhere that he is against theory *per se, much less that Tolstoy is a lesser writer for theorizing, or that Shakespeare’s portrayal of kings is secondary to… what were you even saying there?

One thing to keep in mind is that the piece is written in a very specific context, namely to assess the status of the humanities internationally, and how they’re conceived in terms of curricula. Hence the reference to management speak and the employability of humanities graduates in general. He obviously deplores the shallow understanding of the humanities in the business world, and from government officials, but his point is that it’s at least in part the academics’ own fault.

His central issue is with the linguistic/cultural studies turns, which for all their merits according to him have marginalized empirical studies in universities worldwide. I happen to agree in a general way with that, and it coincides with Franklin’s criticism that theory applied to art risks a dogmatism that is alien to any creative endeavor.

That Kurtzman fits in a cheap shot a comics is perhaps unfortunate, but the greater issue he is addressing, namely the excessive relativization of the canon in higher education, is a pressing and problematic one.

He says Shakespeare is about humanism, and attacks contemporary academia for wanting to talk about cultural context, to which I say, Shakespeare wasn’t a humanist (at least not in the current context where that means a democrat) and had a cultural context. Kurtzman sneers at theory in favor of empiricism, to which I say, lots of writers like Tolstoy question empiricism in favor of theory, which leaves you looking pretty silly if you claim you’re speaking on behalf of literature by bashing theory. And he does in fact come very close to attacking theory per se, inasmuch as he warns over and over about using theory, in all caps even, without ever acknowledging that empiricism is a theory, or discussing the difficulties you run into with pragmatism (which explains his willingness to embrace business speak.) And for pity’s sake, how often do we have to see ignorant humanities types making half-assed references to relativity or quantum-theory? If Kurtzman seems like a straw man, it’s because he set himself on fire.

The cheap shot at comics is entirely in keeping with the general tone of the essay, which claims to be empirical but sets up sweeping definitions of literature and art which have no relation to most of the literature and art created in the history of the world. I don’t care what context you’re writing in; if you end up telling the humanities that they need to adopt rhetoric from the business world, you need to start over.

Relativism has lots of problems, and the chariness of personal evaluative reactions to works of art often mars academic work. But Kurtzman’s piece is just dunderheaded. Franklin’s romantic appeal to intuition, not to mention Franklin’s ability to write an essay with some sort of stylistic flair, is infinitely superior to such drivel.

I just don’t see him saying any of that. He emphasizes humanism because its an aspect of art less well-served by contemporary theory than others, but it seems entirely clear to me that he sees this as part and parcel of the other aspects of Shakesepare’s, or whomever’s art — it’s not like you can separate out the humanism from what else is going on, and Kurtzman isn’t doing that. And come on, are you arguing that Shakespeare’s humanism *isn’t what has kept him alive and relevant? (Kurtzman says nothing about him being a democrat, incidentally).

This is a pragmatic piece pointing out real problems. In one place Kurtzman directly acknowledges that everything is, in a sense, partly theoretical and relative, but for practical purposes the emphasis on linguistic theory and cultural studies in contemporary curricula has marginalized the empirical. It’s a pretty straightforward observation, and one that I’ve definitely recognized empirically in both academic and professional contexts in several countries — deconstructing it using relativist theory misses the point, and risks merely confirming it.

I’m not using relativist theory. I’m using empirical observations. That is, Shakespeare is not what he says he is; art does not work how he says it does; business rhetoric is fucking stupid (okay, that’s an aesthetic observation, but a relevant one, I think.)

Shakespeare has stuck around for a lot of reasons, but no, I don’t think claiming it’s humanism is helpful or true. His language is amazing, is probably the main thing; it’s a formal triumph. He’s also extraordinarily entertaining; those pulp plots really hold up.

Of course Kurtzman doesn’t say anything about him being a democrat. Kurtzman’s committed to claiming that cultural context doesn’t matter; that we’re dealing with universal human truths. And my contention is that that flattens shakespeare, and indeed, all art. Shakespeare’s politics are in your face; they’re very important to him and were very important to his audience (it’s part of why he got patronage.) That doesn’t have to be the only thing you talk about, but to suggest there’s some empirical understanding of Shakespeare that transcends those discussions is idiotic. Shakespeare was ideologically a divine right of kings proponent; that’s an observation that’s way more empirically verifiable than the idea that he validated universal human relationships. It’s perfectly reasonable to argue that empirical descriptions of artist’s politics is not the most important thing you can say about their art, but trying to use empiricism to confirm universal humanism is simply asinine.

Like I said, the problems Kurtzman’s pointing out are real, and I’d be happy to see someone deal with them in a thoughtful way. He doesn’t do that. Instead, he tries to make the humanities a pragmatic, empirical undertaking in the explicit interest of making them more business-friendly. And because literature really is not a pragmatic or empirical undertaking, and because it’s never going to be the best choice for maximizing future earnings, he ends up in a completely untenable and ridiculous position.

The folks who are most successful in attacking Derrida, et. al, in my opinion, are people like Stanley Hauerwas, who believes in God, or Badiou, who believes in revolution…or, yes, people like Franklin, who are willing to turn art into a religion. If you’re claiming that the problem is that there’s no truth, you need to take a stand for truth. Making pragmatic claims for greater market savvy doesn’t make you look like you believe in truth. It makes you look like you’re a tool.

Then thing is, and I guess I’m repeating myself, is that your description of the piece is almost unrecognizeable to me. As I understand it, Kurtzman in no way says that cultural context doesn’t matter, neither does he claim Shakespeare’s politics are irrelevant — he specifically says that we can learn a lot from him still, about being human in particular, and being human includes all those components (even if politics especially tend to date, I guess). And he uses Shakespeare as an example precisely because of his humanism (in the renaissance understanding of the word) — he’s the quintessential humanist, and the qualities you describe in his work tie into that, as I see it.

Anyway, what Kurtzman is opposing, rather, is the neglect of the reading of Shakespeare in favor of comic books (his specific, somewhat asinine example) or whatever other pop culture product that’s in vogue, and especially the reading of theory about Shakespeare or literature instead of Shakespeare himself.

I don’t see the article as an argument for the commodification of the humanities either — on the contrary, its whole raison d’etre is to oppose that same commodification as it’s happening today, where businesses and cultural ministries push for the humanities to be profitable and applicable in a business context. His argument is that if the humanities actually attempted to deal more directly with their core subject matter, rather than getting lost in relativism and closing themselves off in hermetic theoretical discourse that the rest of the world could care less about, they might not find themselves being commodified and devalued quite as easily.

Well, I won’t go at it again. Even I get tired of repeating myself eventually!

I guess in response to your points specifically though…some of the best writing in the world has been theoretical discussion of Shakespeare. Keats’ notes on him are probably most famous, but Coleridge, Shaw…Stoppard too, I’d argue.

And, again, there’s a lot of writing about Shakespeare that doesn’t try to see him as humanist. Iago, especially, is often cited as precisely unhumanist; he’s a trope. The Winter’s Tale, too, is really more about the manipulation of tropes and divine redemption. Shakespeare isn’t about realistic motivations or deep analysis of human character (at least arguably); it’s about the joy of plot, plot, plot and the miracle of drama. The humanist reading is certainly popular, but it’s a reading, not the only way to appreciate him. Humanism in itself is just a pretty weak response to the linguistic turn, precisely because it fails empirically.

I think there’s a failure to realize how strong the connection is between empirical skepticism and the linguistic turn, maybe? You can’t get past Derrida by going back to Hume; once you’re looking to empiricism and skepticism and pragmatism, you’re sunk — that all leads right to relativism and the denial of truth, as it did historically.

A romantic appeal to the intuitive value of art-as-art — not as an expression of humanist philosophy — is a much more fruitful path, I think. I don’t exactly agree with it, but I find it a lot more logically and aesthetically consistent/pleasing.

Well, I don’t disagree that Shakespeare is more than pure humanism (although it’s undeniably crucial, historically), but I don’t think Kurtzman would disagree either — he has a bone to pick with the linguistic turn and cultural studies and their effect on academia. But anyway, you’re right, we’re both repeating ourselves.

Re: empiricism, I don’t think he’s trying to make a philosophical point or trying to argue that ’empiricism’ is better than semiotics or some such — what he’s objecting, as I read it, to is musicology students unfamiliar with Bach or Mozart, literature students who go straight to reading Foucault and Derrida without showing any interest in the literature they’re supposed to be studying. I certainly know this from art history: students mostly interested in theory or cultural studies who never look at actual works of art, can’t tell what media they’re in, and don’t know anything about their history. It’s a very real problem that won’t be solved by arguing which philosophical approach is current or not.

Well, I can’t speak to musicology…but Derrida and Foucault are really literature/philosophy in themselves. They’re some of the most important thinkers of the last 100 years. I don’t really see what’s wrong with wanting to study them rather than wanting to study Shakespeare (though I love Shakespeare personally.)

I mean, just from the conversations I’ve had with academics, I’d think that in general people would be thrilled to have students who wanted to read Derrida. Mostly you get students who don’t want to read anything, whether it be Shakespeare or Derrida or comic books.

I still don’t think that empiricism or pragmatism is a convincing way to approach art. If you want to make widgets, make widgets, it seems like. Art is supposed to be about something else, whether you want to call that philosophy or god or jouissance or what have you.

Matthias, I have grossly misjudged you. My apologies.

Oh good. Glad we’ve all realized that I’m the real enemy…

Noah, you I have only mildly misjudged. You can go suck it.

Aw, the CMS deleted my “kidding” HTML tag.

Well, Noah, I like Foucault and Derrida as much as the next person, but the fact is that most of humanity doesn’t. A much larger part likes Shakespeare or Mozart, and have for centuries. We cannot afford to ignore that.

It’s doubly depressing that you’re probably right about many students note really wanting to read anything (much less learn a different language to do it), and thus not even being that well-versed in whatever theory is popular, but it only compounds the problem if they move straight to theory without some grounding in reality, or at least tradition.

Franklin, no apologies necessary — I appreciated your comments, and you did point out an inaccuracy in my piece, reminding me to write better in the future.

Now, why do you think Habibi is good? (If indeed you do).

Wait…now art is a popularity contest? If that’s the case, I suspect the Beatles are more popular than Mozart, probably even if you go by total people who have listened to or purchased their music (population growth is on their side.) And I suspect Harry Potter has been more widely read than Joyce’s Ulysses. Does that mean the first should replace the second in university curriculum?

This is why empirical figures for art are nonsense. You want to overturn the relativists, take some sort of absolute stand on quality or get out of the game.

It seems to me that we’re missing a very important point here: Foucault and Derrida aren’t alternatives to Shakespeare et al. Foucault doesn’t send the Panoptican Patrol to snatch the Shakespeare out of your hands. If anything they’re alternatives to Locke and Kant et al. Theory isn’t not some sort of “new thing” in the humanities — it’s just interdisciplinary philosophy. It’s a subject and a discipline in its own right. It’s more like what came before than it is different.

Theory can’t be made into a scapegoat for poor quality work in academia. The crisis in academia isn’t theory’s fault – theory is what academics make of it, what they do with it, like any philosophy is what people make of it. The crisis in academia is the fault of a god-awful publishing structure and a system of tenure that rewards pretty much everything other than public engagement, including evaluating teaching in terms of enrollment and the opinions of 18 year olds, and “responsibility centered management” in university departments, and mass media and the academic versions of the same centralization of capital and influence and the same demographic pandering that’s happened everywhere else in our society.

As for the value of humanities education in the workforce, see paragraph 1. The sentence from the article says: “Graduates need to be able to show the ability to learn something specific and be able to handle that subject’s material knowledgeably and effectively. It doesn’t matter whether that knowledge is in French Literature, Nineteenth-Century Continental Philosophy, Danish History, or medieval music.” That’s absolutely true.

But Twentieth-Century Continental Philosophy, which is loosely what academia uses the shorthand “Theory” to refer to, also belongs on that list. I’ll wager that of the four of us talking here — Matthias, Noah, Mr Kurtzman, and me, I’ve got the most corporate job of any of us, and I’m also the one most steeped in Theory. And that training serves me just fine, because the skills I use when I’m facing down a team of 15 people with four days to produce documentation for a $45M contract offering are curiosity, agility of mind, and the ability to think critically and ask questions. My knowledge of Theory itself doesn’t get in the way of any of those things, and the work I did learning Theory is one of the places I got those skills. If academics fail to teach curiosity, agility, and critical thinking alongside their theory, the problem isn’t theory — it’s those academics and their priorities. Indoctrination isn’t education — but it’s largely irrelevant what you’re being indoctrinated into.

Theories in the humanities are heuristics – engaging with them leads to flexibility of mind through the attempt to reconcile contradictory perspectives and to map their intricate structures against each other. Theory in the humanities doesn’t teach you that Truth doesn’t exist — it teaches you that Truth is incredibly complicated. If all you do is memorize a Theory, believing it to be True, then regurgitate it back, or apply it bluntly and uncritically, you’re missing the point, and probably doing terrible work. BUT THE SAME THING is true if you memorize your chemistry textbook but never ask probing questions, never ask what stoichiometry or thermodynamics have to do with the atomic theory you learned in physics or the ecology you learned in biology. Agility of mind and curiosity is independent of subject matter.

I think the problem isn’t that there’s too little investment in Truth; it’s that there’s too much investment in being right — and in convincing people to believe you’re right for the interest of power, whatever sort of power you’re interested in or entangled in. And you see that investment among people in the humanities, from academics, but also from Creationists, from scientists, from political parties. Blaming that on theory is missing the truths that might actually make a difference.

Sorry; not to be too flip about it. It’s really hard to figure out a way around relativism, I think. Why should someone pay attention to Shakespeare rather than Derrida? Or Derrida rather than Harry Potter? Or whatever? You end up having to appeal to popularity (which doesn’t work at all) or long-standing importance (which is just an appeal to tradition), or else you’re down to quality, which people are going to disagree on quite radically (someone out there thinks Harry Potter is better than Shakespeare…probably a lot of people.)

“”Graduates need to be able to show the ability to learn something specific and be able to handle that subject’s material knowledgeably and effectively. It doesn’t matter whether that knowledge is in French Literature, Nineteenth-Century Continental Philosophy, Danish History, or medieval music.” That’s absolutely true.”

See, I really don’t think that is particularly true. Content matters a lot. Sure, what humanities you learn maybe doesn’t matter, but that sort of ignores the fact that that’s mostly because nobody gives a crap about the humanities in the first place. Law and economics and business; you’ll make a lot more money with those on average than with the humanities. Anyone who is getting a degree in the arts and humanities has already made a decision that they’re not planning to maximize their earnings.

And while I guess critical thinking can be useful, I think having connections and luck is a lot more important in the long run. The idea that somehow the economy rewards the best and brightest is just silly. Lots of people who have succeeded in the corporate world are as dumb as rocks, just like lots of people who succeed in academia. It’s nice to think that critical thinking skills and virtue will be rewarded, but it seems like a fantasy to me.

For the rest…people are always going to be invested in being right. It’s like Octavia Butler says; the tragedy of the species is that we’re intelligent and hierarchical.

I’m not sure that’s relativism so much as pluralism. You’ll never get any kind of consensus on those things…

Yeah…but that’s a real problem if you’re insisting on a canon that’s supposed to have some sort of empirical and/or transcendent grounding.

Sure, there are differences between what I earn now and what I would have earned if I’d gotten a degree in data architecture or law, but, a handful of lucky elites excepted, there’s a much more meaningful difference between what I earn and what people who don’t have either strong critical thinking skills or subject matter expertise earn. And those skills aren’t always directly tied to a degree, especially in IT. And I have the opportunity and the ability to go get one of those degrees that will increase my earning power; folks who wait tables at diners are a lot more restricted.

I think that notion of an empirical canon is a complete red herring, though. Just a different “Theory” that satisfies a desire to have access to the right answers.

Getting a degree is really important…but I’d argue that’s a lot more related to class status going in on average than to the actual skills you learn in the humanities in college per se. Or, to put it another way, by the time you get to college — hell, arguably by the time you get to first grade — a lot of outcomes are already set. Having your parents read to you a lot when you’re little is way more important than how well your professor does or doesn’t teach you theory. Having enough to eat when you’re little is probably exponentially more important than that, even. Class-as-position-in-society is a ton more meaningful to these questions than class-as-room-in-which-you-are-taught.

If you’re serious about improving learning outcomes and earning potential, squabbling over the place of theory in the humanities curriculum just seems almost ludicrously beside the point.

And again, this is a really serious and ongoing problem for the humanities. There simply is not a good way to make the case for humanities studies, with theory or without theory, in terms of economic outcomes. And economic outcomes are the thing our society cares about most.

“squabbling over the place of theory in the humanities curriculum just seems almost ludicrously beside the point.”

But that’s my point! Theory in the humanities curriculum is the wrong bugbear here.

Wait…you’re saying I’m arguing just for the sake of arguing? Not me, surely….

Ha ha. You’re just still arguing with Kurtzman.

I agree with Kurtzman (and Franklin) that there’s tons wrong with the humanities curriculum; I just don’t think it can be pinned on Derrida. In part because, as Craig pointed out on another thread, “Theory” has already been largely replaced in the academy by Cultural Studies, and things have gotten even worse.

I think the problem is that the logic is circular — it’s hard to make the case for any kind of expertise or interest that doesn’t have direct positive economic outcomes, because to do so you have to make reference to values other than economic ones, and that doesn’t get very far: people always respond with economic arguments that diminish the importance of everything else.

The academy was just as bad for modernism. When I was down in Augusta last October I chatted with a painter associated with ASU named Philip Morsberger. Phil remembers going into a figure drawing class in the ’50s and getting scolded because his drawings looked too much like the model. Everything was supposed to be abstract, see? Suddenly I understood where all the irritation at Clement Greenberg came from. Greenberg himself was blameless. Droves of lesser practitioners turned the anti-method of modernism as described by Greenberg into a method, and brought it into the classroom. Better students rebelled, which is what real modernism indicates that you should do in the face of an aesthetically enervated method.

This is why I make a distinction between postmodernism and academic postmodernism. Postmodernism is a neutral fact about the intellectual landscape. Academic postmodernism is an aberration. The analogous phenomenon of academic modernism, which has pretty much disappeared at this point, was guilty of creating a similarly stultified creative environment.

So I mostly agree with Caro that we can’t blame Theory for poor academic work, with the caveat that Theory has a mark against it for never having existed outside of academia. Practitioners, not academics, gave us abstract expressionism, comics, jazz, and most of our more interesting creative advances over the last century. Some of those folks may have gone to school or taught at some point in their lives, but Theory is a different sort of thing, one that would have been inconceivable without academia to bring it into being. Academic postmodernism is a survival strategy for academia. And it has certain traits (particularly, stylistic tics) that make it especially suitable for that purpose.

Franklin said: “Theory has a mark against it for never having existed outside of academia. Practitioners, not academics, gave us abstract expressionism, comics, jazz, and most of our more interesting creative advances over the last century.”

Across the disciplines, though, this isn’t entirely true. The body of work that America broadly calls “Theory” was in part created in academic contexts, absolutely, but it was also emergent from the culture of Apollinaire and Bazin and Langlois and Cocteau, and most of all from extremely lively French politics. The French academics who wrote much of this theory weren’t in an academic ivory tower; France has a different sense of public artist and public intellectual than we do. That isolation in the academy that you point to is mostly true just in the US context — where I think the problems you rightly identify with academia have distorted theory just as much as they distort art.

Likewise postmodernism in literature was a movement more like Surrealism or Vorticism in art — a product of practitioners who were also theoreticians. Pound and Wyndham Lewis (who also wrote about visual art), were modernist practitioner/theorists who directly influenced postmodern writing. Postmodernism emerged as much from writers like Burroughs and Ginsberg and Cooper and Beckett and Brecht — from their work and from their ideas about that work — as it did from non-practicing academics writing about them. Practitioners in architecture were grappling with these themes, as were musicians like Schoenberg and Stockhausen and Webern and Philip Glass. Think about the writings of Tzaba or Breton or Borges.

I think a lot of this is just the difference in disciplinary perspectives and cultures; there’s a long tradition in visual art of distaste for “academic art” — but there’s an equally long tradition in letters of the academy providing safe harbor, and stable employment, for experimental writers. More importantly, literary criticism and theory have long been part of the practice of fiction writing. It’s all writing — it’s not as either/or as it is in visual art. So the academy historically has simply not been all that stifling for writers, at least not until recently when the Program has introduced effects and stylistic pressures far more similar to the situation in art. But the Program is, broadly speaking, the least Theoretical environment in academic literature. It’s a different set of pressures, and the sources of those pressures are complex and historically situated, not some straightforward effect of Theory.

Theory’s ascendency in the academy coincided with the academy retreating from public life — but I don’t think that’s simple causality. Culture also became increasingly democratized, less interested in elites and less engaged with history, during the same period. There weren’t really any pressures from outside to prevent the academy from becoming insular and jargony, the way there had been when academics still regularly talked to the public in various wide-reaching forums.

I think there needs to be a careful distinction between “academic” and “theoretical” – because the problems with academic work and academic power aren’t all due to that environment’s comfort with theory, and the particularities of theory aren’t all due to its standing in the academy. It’s possible to tease out elements in academic work that are insular and serve no purpose other than self-perpetuation, but those elements are supported by structural factors like the systems of publishing and tenure. Without care to draw the distinction between the academy and theory, a valuable critique of academic power politics can too easily turn into a kind of knee-jerk anti-intellectualism that polices taste just as much as academic canons and theoretical posturing do.

People should talk about Philip Morsberger more — I have a wonderful book about his work subtitled “A Passion for Painting”: http://www.amazon.com/Philip-Morsberger-Painting-Christopher-Lloyd/dp/1858943760 Delightful stuff. How lucky you were to meet him!

Derrida doesn’t literally snatch the Shakespeare out of your mitts. Instead, some boring, tenured potentate dangles a credential in front of your nose and says that you can have it if your Lacanian psychoanalysis of Henry IV sufficiently resembles his. Next thing you know you’re mashing Habibi through the postcolonial sieve with which you puree everything you read.

Ginsburg and Cocteau are hardly the central figures of Theory. Derrida, who is, hardly ever walked off campus from the time he was in his twenties. No, there’s a peculiar tenor to theory that can’t be blamed on academic publishing and tenure, as baleful as they are. What gets published and who gets tenured are not accidental choices, just as this confluence of shitty art and shitty criticism is not an accident. Whatever reasons that academia became “insular and jargony,” the fact remains that Derrida et al. were insular and jargony from the get-go, which serves the purposes of academic survival in a way that, say, romanticism does not.

Charges of anti-intellectualism are the defense of first resort among academics, for obvious reasons. It would be healthy if one of them recognized that turning your discipline into a massive exercise in confirmation bias is not a productive intellectual activity. (Oh look, I just got a press release from the Brooklyn Musuem that reads, “Video Installation Features Dialogue among 150 Diverse Black Men.” Video! Installation! Dialogue! Diversity! Blackness! I think I just had a postmoderngasm.)

Meeting Morsberger was pretty great. I’m selling him short by saying that he’s associated with ASU. He’s the William S. Morris Eminent Scholar in Art, Emeritus at the university, which is an appointment commensurate with international recognition.

But Craig Thompson talked in interviews about deliberately thinking about Orientalism in creating Habibi. Are critics supposed to ignore that? If he explicitly says that he used Orientalism, isn’t an evaluation of the effectiveness of that use worthwhile, or called for? And if so, it seems like there has to be the potential to say, you know, this didn’t really work. Otherwise criticism just becomes hagiography.

Derrida is really jargony, but not moreso than Kant. Philosophy is just aggressively abstruse. I’d agree that that’s a problem, especially when (as recently) there’s a claim that it has some sort of democratic or liberatory potential. But it’s definitely not a new difficulty.

Foucault is actually often pretty accessible as these things go, though. And Said is quite fun to read; a really clear writer making not-at-all counter-intuitive points.

I’ll admit that the video installation sounds like it could be fairly awful…though it’s hard to tell without seeing it (or at least hearing it described more fully.)

Do you just automatically hate video art or installations? It seems like it’s sometimes good and sometimes bad, like anything else. My son and a friend of his were really taken with Nick Cave (the artist’s) soundsuit videos, for example…which are, among other things, about his blackness (they’re inspired by traditional African masks and dress, I believe.) They seem really accessible to me, and very much postmodern…I don’t know. Do you like him, or is he part of the academic post-modernism you’re decrying?

While I’m really enjoying this debate, and sympathise with so much of what Franklin is saying, I still find it difficult to reconcile that with a defence of Habibi.

I’m just not sure that Orientalism is purely a concern of Theory or Academia, any more than racism is. Its a political and social issue too, and it seems perfectly legitimate, and indeed quite empirical and non-theoretical to evaluate a piece in the light of a political and social context, particularly if its a piece which openly admits to be engaging with that context.

Like I say, fascinating debate, but I’m really unconvinced that Habibi deserves to be its source.

It seems like there has to be the potential to say, you know, this didn’t really work.

I fully agree. But there also has to be the potential from the same persons to say that it did. I can’t judge whether that’s happening except via the same mechanism that you suspect that the video installation in the press release sounds like it could be fairly awful. It may be meaningful and moving, and the only way to decide for sure would be to see it in person. But in the meantime it sounds like someone is parading their postmodernist virtues and thus fully invested in art-by-checklist as I described earlier.

Cave is the real deal.

————————–

Franklin says:

…Next thing you know you’re mashing Habibi through the postcolonial sieve with which you puree everything you read.

—————————-

Heh! Beautifully put…

The properly reverential attitude: http://www.artcritical.com/blurbs/JSMcMillian.htm

Hopelessly out-of-it Dave Barry’s reaction: http://www.washingtonpost.com/ac2/wp-dyn?pagename=article&node=&contentId=A36804-2004Jan21¬Found=true

——————————

Noah Berlatsky says:

But Craig Thompson talked in interviews about deliberately thinking about Orientalism in creating Habibi. Are critics supposed to ignore that? If he explicitly says that he used Orientalism, isn’t an evaluation of the effectiveness of that use worthwhile, or called for? And if so, it seems like there has to be the potential to say, you know, this didn’t really work…

——————————–

Certainly. Although, wasn’t he more jabbed at for uncritically using Orientalist tropes, Thompson blithely comparing their usage to doing a Western?

(I imagine if he’d done the latter, he’d have been surprised that a book with good-guy cowboys gunning down hordes of bloodthirsty, savage Redskins would offend…)

It’s not that I’m disagreeing with you about the insularity of academic theory, Franklin. I completely agree with your point about confirmation bias — it’s exactly why I left the academy. I just think you’re underemphasizing how much of that insularity was there before 1968, and overstating how much it intrinsically corrupts the particular body of ideas that fall under the rubric of capital-T Theory. As Noah says, Derrida and Lacan and Althusser are not more abstruse than Husserl and Hegel and Koyre. They metastasized out of their disciplinary casing, I suppose, but reading Derrida isn’t that different from reading any other philosopher.

So I guess I just don’t see this tenor to Theory that corrupts it absolutely? Absolute fealty to any theory, especially heuristic ones, at the expense of imagination, is corrupting — but it’s corrupting regardless of the theory.

I think one of the things that gets in my way here is that there’s a distinction in literature between Theory and Postmodernism that doesn’t seem to exist in visual art. Postmodernism in art seems to traffic so much more in axioms than it at least used to in literature. Postmodernism really is an American writers’ movement in a way that Theory isn’t. You’re right that Theory has no organic roots in this country outside of the academy. But postmodernism does. So are you saying that postmodernism has a uniquely academic tenor that corrupts it, or just the Continental stuff? Because maybe what’s throwing me off is just this different perspective.

Ginsberg isn’t really “Theory” in the strict sense, to me — although he and Burroughs really are central figures to postmodernism. To imagine postmodernism without the Beats, without the experimental writers of the ’60s, without Sam Delany and Kathy Acker — I can’t do that. Any “theory” of postmodernism would evaporate without the contributions of those writers. It’s so deeply inmeshed in writing practice to me that I just can’t see it as academic in the same the way you do. I know there’s Theory like Lyotard on postmodernism — but that’s really poststructuralism (which is indeed extremely academic) talking about postmodernism. The fact that the academics eventually wrapped it in jargon as they are wont to do doesn’t negate the 25-odd years when it was a very organic part of American writing and expression.

Not that you’ve ever claimed to be talking about writing, and perhaps postmodernism has played out very differently in art. I just think it’s important not to see Delany and Acker and Burroughs as “academic” writers, especially Acker, who died homeless and very ill without insurance. I only wish the academy could have provided her the same succor in later life that it did to others of her generation.

But the truth is that something similar went on in Theory, if you widen your frame past the American academic version of it: Theory does not have organic roots in the US, but it does have organic roots in France. (Sometime next week I’ll be talking about Althusser and Godard…) Derrida is very much a Johnny-come-lately figure in what we call Theory; he’s just the academic celebrity who put it on the US map. Making Theory about Derrida is like giving Stephen J Gould credit for the theory of evolution — it’s not that Gould has nothing to do with how we understand evolution or how it plays out as a cultural force; it’s that you don’t get the big picture if you put him at the center of your analysis.

In US literature departments, Lacan is actually more central to Theory than Derrida, in truth, as fealty to Derrida is more axiomatic than anything (i.e., the details of his work rarely show up as an influence on any particular reading). Lacan was ejected from the French academy for being too weird. He hung out with Langlois and Godard at the Cinematheque. He was friends with and directly influenced Bunuel and vice versa. He showed up on French talk shows. Foucault and Althusser are probably the most central to Theory in the humanities overall — and although they were indeed academics, they were also involved in French political life in a way that academics in the US never ever are. They weren’t artists, but their work wasn’t ivory tower — it was directly responding to specific political debates and challenges over the status of French Communism after the war and in the wake of Stalinism, and to the realities of French life in the mid-century.

Not to imply that Derrida isn’t academic — Derrida took this constellation of ideas that was very lively, very organic, and very broad-based, he transposed it into an immensely esoteric philosophical context, and then he exported THAT to American universities. And Americans looked at the export and said “that’s the real thing, baby!” But it was actually pasteurized and homogenized in that uniquely academic way because the US doesn’t let raw food through customs, and because Americans, even academic Americans, especially academics in English departments which led the Theoretical charge, tend to be both romantically attracted to and slightly befuddled by politics in foreign languages.

I’m 100% behind your critique of the pasteurized, homogenized export and the way it’s been a bludgeon in the hands of people with incredibly self-serving and insidious interests. I left the academy because, in my opinion, the environment was every bit as stifling to imaginative, meaningful, engaged THEORETICAL work as it (apparently) is to imaginative, meaningful, engaged artistic work. But the solution to that isn’t to enforce some kind of artificial boundary where theory belongs in and to the academy and art belongs to the world. Those are incredibly false distinctions that lead precisely to the kind of theory you don’t like, and in the process aid and abet the power structures of the academy. Nobody wins there.

What do you think of a writer/philosopher like Sartre? Is he also corrupt in this academic way, because he’s revered in the academy and because he wrote both fiction and theory? He’s something of an archetype of the French intellectual tradition to me, and I think his influence on the emergence of Theory in France, especially his influence on the type of conversations these thinkers had with each other and with the society and his importance in establishing the context for the intellectual foment of France in the 1960s, is terribly underemphasized by academics, partly because he stands as a demand for public engagement that academics do not want to be responsible to.

Or Zizek, for example, who when slammed for writing copy for Abercrombie and Fitch magazine, replied “If I were asked to choose between doing things like this to earn money and becoming fully employed as an American academic, kissing ass to get a tenured post, I would with pleasure choose writing for such journals!” That’s the same spirit I think you’re seeing in and asking from artists — but there’s hardly anybody in existence who is more Theoretical than Zizek. Does he just not count because his imagination is analytical rather than expressive?

Thanks Caro, for that second post — your first seemed to me too much of an apologia for the ravage theory and cultural studies have caused in the humanities in the last couple of decades. I understand why you quit and agree that it’s not the ideas of these great thinkers themselves that are the problem, but rather how they’ve become codified in too much of academic discourse.

My point from the beginning was not to dismiss theory (or Theory) but speak to the deplorable effect it has had on the humanities. I agree that the other things you mention in your previous post on the troubles in academia are even more serious contributing factors, but the problem with the hermetic turn in academia is that it plays into the hands of the market, exacerbating those problems — when no one, least of all the academics themselves, can justify what they’re doing, the world at large is going to stop taking them seriously and demand that they pay their own way.

Theory and cultural studies have a lot to offer, but they’ve been institutionalized in a way that has made humanities scholars neglect one of their noblest calls — communicating with the rest of the world.

And no, Noah, I obviously don’t believe art is a popularity contest. On the contrary. Which is in part why I believe tradition counts for something: should it be challenged and adjusted? Of course, but letting relativism do it in and leaving its treasures at the mercy of the market is hardly the way forward.

Caro, the full extent of my claim is that Theory has been especially useful to academia in its insidious forms, and some of the reasons for this are intrinsic to Theory. Do you dispute this?

Speaking as somebody who made some feeble efforts to write poetry in an academic setting…I think there’s really no part of the arts that’s as debased as contemporary poetry (contemporary art doesn’t even come close.) And theory has very little to do with the shittiness of contemporary poetry. There are certainly some very pomo poets (like John Ashberry) but they certainly aren’t worse than their confessional, non-theoretical peers. As far as my own writing was concerned, my interest in theory and post-modernism was probably partially responsible for my lack of success — nobody in the MFA programs wanted to read satirical bricolage about how MFA programs are debased as it turns out. Which is to say that academic poetry likes its theory carefully circumscribed.

I think there’s some truth to the idea that Derrida and Lacan are appealing in part because they’re incomprehensible; the humanities has a craving for technical jargon which will make them more like the social sciences (which has a craving for tehcnical jargon which will make them more like the sciences.) But again, theory is just abstruse because philosophy is abstruse, and I don’t know that the humanities flirtation with abstruse philosophy is all that new….

A big part of the problem is that academics write badly. The difference between Zizek and everyone else does come down in a lot of ways to prose style; he’s aesthetically accomplished, which matters a lot. I think this is exacerbated in art, where even minimal competence in writing often doesn’t exist (just as if you asked a bunch of writers to justify themselves through illustration, you would get a lot of crappy illustrations.)

It’s funny; I tend to forget how utterly soul-crushing my academic experience with poetry was until I have these talks with you, Franklin. These days academia for me is just the source of various books I read and enjoy, and the place some of my readers come from. That kind of voluntary relationship with it is a lot more pleasant. When I was trying to fit myself into that hole, I was plenty miserable.

Grad school in history was fine, though, mostly. The arts were bad news though.

Franklin, I’m honestly not sure. Are you saying that those useful things are intrinsic to Theory/Continental Philosophy and not to other schools within philosophy? Something that Derrida or Foucault enabled that Husserl and Nietzsche, especially had they been transposed into the arts, would not? Are you including the practice of Postmodernism in that claim?

I don’t think Theory has been of any greater use to the politics of the humanities in that respect than pragmatism has been to the politics of the social sciences, etc. (And the social sciences have had some more insidious affects overall, especially in the early 20th century.) And as I commented on the other post, I think it’s really hard to extrapolate from fine art, where the market factors you and Matthias are both so legitimately concerned about have a much more powerful effect than they do in the humanities overall. I don’t really see literature’s hermeticism with regards to Theory playing into the hands of the book market nearly as much – the book market is thoroughly uninterested. It can and has created a demographic out of those people but that demographic is hardly powerful in the overall scheme of things. I think the art world has had to have a very relentless blind spot to Theory’s insistent Marxist lens in order to maintain and intensify the academy’s relation to the market. When you talk about Theory, are you within that blind spot or without?

In my mind Theory as the body of ideas from Continental Philosophy (rather than several different specific academic practices) is just not monolithic enough for me to even really be sure what you’re referring to when you talk about something “intrinsic” to it overall. Is there anything that’s intrinsic to Gramsci, Lacan, and Deleuze, all together? (Other than their “theoryness” which they also have in common with Kant and Schroedinger?)

I agree with Matthias 100% that the humanities have neglected, even abandoned, the call to speak to and with the public and that this is incredibly insidious. But I don’t think that Theory really caused that. I think Theory exacerbated it, because it takes a lot of work to talk about Theory without jargon. But I don’t think that Continental Philosophy in particular entails hermeticism. People can always retreat into their philosophies, and they do. The “hermetic turn” (what a great phrase) probably would have happened without Continental Philosophy, due to changes in journalism and changes in the profession of academia. So many things in our world are hermetic — Fox News comes to mind. And it continued, even worsened, as Theory receded and Cultural Studies rose to the fore. I agree with, you, Matthias that hermeticism makes the academy more vulnerable to market forces that are bad for the academy, but I think the hermeticism is a symptom of other things, not an effect of theory’s discursive power within academia. The academy has been hermetic for a much greater percentage of its history than it has been publicly engaged. If there had been value to academics in remaining engaged, they would have remained engaged. I guess a see a dialectical decline there rather than a linear one – academia’s natural hermeticism and Theory’s natural left politics feeding off each other cyclically in the West in a late Cold War context to the mutual destruction of both.

Really, I think the hermetic turn underlines how much academics have failed to be attentive to the Theory they claim to follow – a great deal of the most influential Theory contains a demand for public political engagement. How anybody can read Althusser and Foucault or Zizek and Kristeva and retreat into the ivory tower is just completely beyond me.

The flattening of Theory into the kind of checklist you’re talking about, Franklin — that’s not intrinsic to Theory; that’s intrinsic to academia. Academics did it with modernism as you point out; they did it with New Criticism; they do it with various forms of empiricism and positivism. There’s certainly nothing intrinsic to Theory that prevents it from being used in that way, but I don’t see it being particularly structurally unique.

But again, I think you use it differently from the way I do — I think we’re denoting slightly different things by the term. It’s only at this extremely meta level that I even call it Theory, so it’s obviously a much looser and broader term to me than it is to you. When people in art talk about Theory it always sounds monolithic, but I don’t know what that monolith consists of. To me there is poststructuralism and postmodernism and post-Marxism and the various feminisms and then the cultural studies pieces that grew out of postcolonialism. They’re all really different, and the post-Marxist feminism in particular that I would align my own politics most closely with is very much at odds with many of them, especially the heavy identity politics of the postcolonials. I’m Zizekian in my stance on universality, which puts me at odds with Butler and most of the postmodernists. So I’d hesitate to make a statement about “intrinsic” properties when the term to me is so broad and contains so many things that can’t easily be reconciled with each other.