Ok, here’s the deal. At Noah’s request I’m publishing here (in blockquotes below) what is largely an unrevised text of a rant I posted on the comixscholars listserv, a rant written as fast as my fingers could type. I would have liked seriously to revise it, but time is, as always, in short supply, and besides Noah says he likes the energy of the original post, so I’ll let it go with just minimal copy-editing and corrections of typos, plus the expansion of a few points I’m not sure were clear enough in the first version.

First, though, I should explain where it came from. When Holy Terror first came out, I didn’t bother to pick it up; no matter how much I’d admired Miller in the past, and how important most of his work from his early run on Daredevil to Batman Year One and Elektra Assassin had been and still is to me, I had been burned too many times since then, especially by the nadir that was The Dark Knight Strikes Again. Nevertheless, I soon found myself in a bookstore, skimming the new book; and though I didn’t purchase it on the spot, it stayed with me, an unscratchable itch to explore it in more depth (it certainly looked better than DKSA—none of those horrid gradients!—or the recent installments of Sin City). I finally gave in, bought it, and meant to review it—but by that time two things had happened: first, consensus had built up online that it was a disastrous career-ender, and hideously paranoid and anti-Muslim to boot; and secondly, Miller posted his notorious blog post fulminating against the Occupy movement, which brought even more contempt rained down upon him. Honestly, at that point I didn’t care about the book so much that I wanted to take the plunge into these muddy waters, and to brave the comment-shitstorm that would have been sure to ensue.

So I decided not to review: yet, even after that decision, I found myself turning back to Holy Terror, and in a strange way my fascination with it grew. And then—and then, two more things happened. A strangely belated discussion about it started a couple of weeks ago on the said comixscholars listserv; and Ken Parille posted a review of the book on the Comics Journal website. Ken’s post was the first I had seen that had something both positive and articulate to say about it (though in the end I didn’t quite agree with him), and that managed to see past its (perceived or real) paranoia and xenophobia to address the substance and artistic achievement of the book itself.

When the thread on comixscholars-l started, I first dipped a toe in with the following remark, appended to a commentary on its supposed “Orientalism” (a question to which I return below):

“Holy Terror” … is an utter mess (and politically abominable, I hasten to add, to shore up my bien-pensant credentials) but in a way kind of a fascinating one. I keep meaning to write about it somewhere.

Ken then chimed in to say he agreed with me, and linked to his TCJ review. However, while I had called it “an utter mess” he discussed it there in terms that made it seem much more conventionally successful: “It’s a fascinating hard-boiled love story, an attractively designed romance set against the backdrop of a post-9/11 America in which love is a disease… Holy Terror’s artistry triumphs over its political will.” He also ended up giving it an A—higher than Habibi, Carnet de Voyage, and Asterios Polyp (relative judgments with which, I should add, I don’t disagree). When the discrepancy between his and my verdicts was pointed out, he explained that he found it a mess ideologically, but successful artistically. This was the immediate cause for my rant, which, none too soon, follows (images added for the sake of clarification):

Now I’m wondering if we read the same book… :) As I said, I do find it fascinating–and I’ll get to that in a second–but it is a mess far beyond just its ideological message. To begin with, the plotting is so rudimentary as not even to deserve to be termed “plotting.” Notice how the book is divided exactly in half, presumably originally for publication in two installments, but also corresponding to the two periods in which Miller is supposed to have worked on it, and easily distinguishable from each other by the utterly different inking treatment (first half, splashy; second half, mostly linework and large areas of solid black). So. First half: Not-Batman chases Not-Catwoman across the rooftops of Not-Gotham City. They fight. They have sex. Bomb explodes. Nail ends up in Not-Catwoman’s leg. It hurts. It really hurts. It really REALLY hurts. We hear about it for pages on end. Flashback to suicide bomber. Same bomb explodes again–NAILS! The city lies in ruins. Not-B and Not-C swear revenge. As does Not-Commissioner Gordon.

[Note: I borrowed the “Not-Batman” and “Not-Catwoman” coinage from other reviews I had seen across the web. Indeed, soon after writing the original rant, I googled the two terms, and found a review that contained a sentence extremely close to the one right before this note, including the term “Not-Gotham.” I honestly don’t think I had read that review previously, and maybe it was just a case of serendipity, but I may also have indeed read it, and forgotten all but that one phrase that remained stuck somewhere in the back of my mind. To the writer of said review: apologies for my unintentional borrowing.]Second half (interspersed with montages of terrorists and various US and international political and public figures): Not-B and Not-C (who has quickly gotten over her wound–and, by the way, may I ask why she’s supposed to be wearing Christian Louboutin sneakers?) swing over the rooftops.

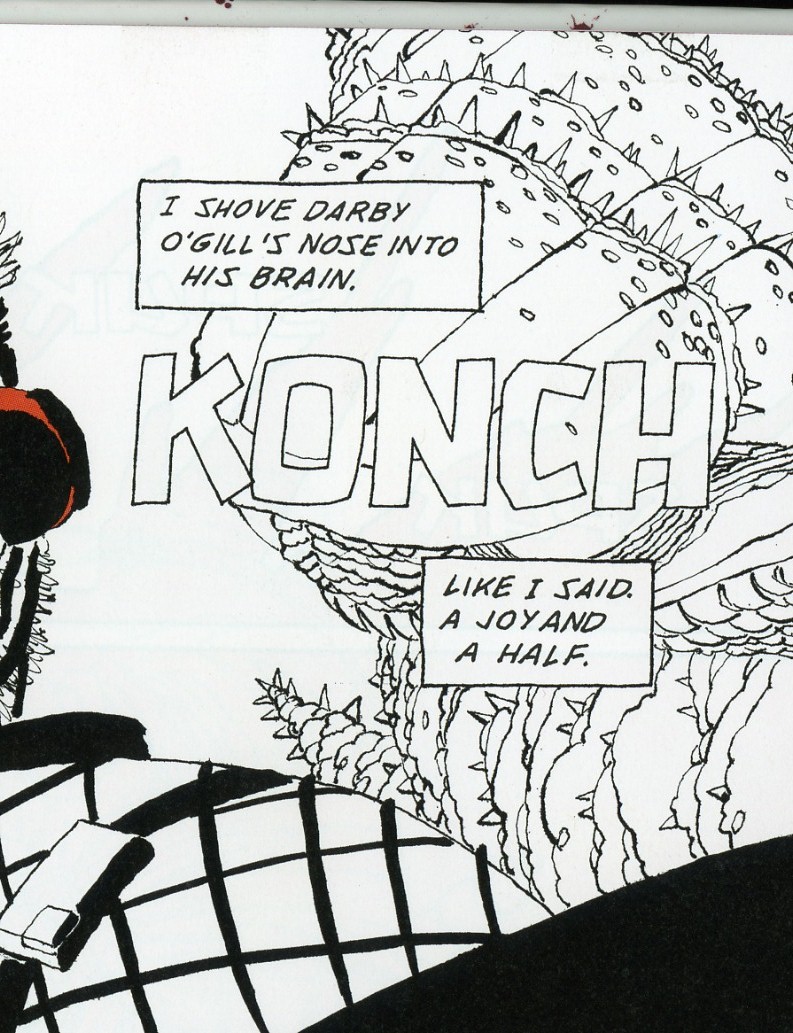

They kill some bad guys, capture one and torture him… He talks and then they blow him up. Meanwhile a Muslim woman is being stoned and Americans are watching “Transformers.” More bombs–Not-Statue of Liberty is blown up. Ex-Mossad agent, whom we know is Israeli because he has the Star of David tattooed on his face (always a good choice, tattooing your country’s flag on your face when you’re trying to be a spy) tells them about the Not-Gotham City mosque, center of terrorism. Bizarre undeveloped subplot about Not-B falling in love with Not-C. Generic Muslim man beating up his wife. Not-C goes into the mosque. Is captured and taken to the leader of the terrorists who turns out to be, umm, Irish? They want to kill her, Not-B swings in and blows their heads off, big scary bomb explodes but somehow they manage to get out. Six weeks later: Not-Commissioner Gordon is shivering in his bed. “No wonder we call it terror.” The end.

There is no narrative arc, no suspense, no attempt to develop the characters beyond the purely convenient labels of their names. All of these things Miller would have been able to do quite masterfully back in the Daredevil or DKR days, but by now any hints in such directions have become nothing but narrative tics, empty gestures. Maybe Batman telling Catwoman that he is falling in love with her might have meant something–a tiny tiny something–if those had been the actual characters speaking, with decades of history behind them, but replacing them with Not-Batman and Not-Catwoman, simple place-holders undeveloped in any way beyond simply being not-the-characters they had started off as being, reveals how whatever romantic punch this narrative element was supposed to carry would have been totally unearned, as it relied *entirely* on the readers’ previous knowledge of the characters. Same goes for Not-B’s constant reference to “my city.” If this had been Batman speaking, ok, it might have resonated with Miller’s earlier work–but since it’s not, it again reveals Miller’s reliance upon shorthand and the readers’ previous emotional cathexes, and it comes off as–I don’t know how to put it exactly, but not plotting, simply the emotional exploitation of stereotypes stored in fans’ psyches.

Then there are all the narrative tricks which, once again, seem like foggy reminiscences of when Miller knew how to tell a story: the thought-captions in the first section come directly from DKR, but, again, seem blank, just storytelling tics that carry none of the psychological weight that they carried two and a half decades ago…

So, what do we have instead? Things happen, done by blank characters who are brought on stage for the sole purpose of enacting a revenge fantasy. For that reason, I suppose, they need have no more personality than figures in a masturbatory, erotic fantasy need have one. The plot again (shorter version): Terrorists do bad things to us. We kill them. The end.

That’s also why, I should add, I was saying there is little actual “Orientalism” in there: the bad guys are as much blank placeholders as the good guys. There is none of the Orientalist texture of, say, “300.” Everything is just… empty.

Further issues with the storytelling? How about the strange crosscutting, in the second half, between Not-B and Not-C’s doings, and the montages of characters from Bush and Cheney to Obama? Is this happening in one night or over a decade? I suppose a sympathetic reading might make one of those strands extra-diegetical, as if the book reflects both the time of its story (one night) and the time of its making (ten years)–but, if so, I don’t particularly see that as intentional on Miller’s part.[Note: on second thought, maybe it is, or maybe the book itself knows, and says, things more clearly than its author might.]

Ok, the positive (not yet the fascinating): yes, there is all the narrative energy in the first half, a mastery of dynamic art, etc.–everything that Ken pointed out–but, while not as bleached out as the narrative tics I was talking about, it still reads like Miller on auto-pilot. All the splashed ink and white-out in the first half seem like an attempt to go in the direction of more “artsy,” painterly artists such as Sienkiewicz or McKean, and it’s fine, well-done, but again, to me not earth-shattering in any way.

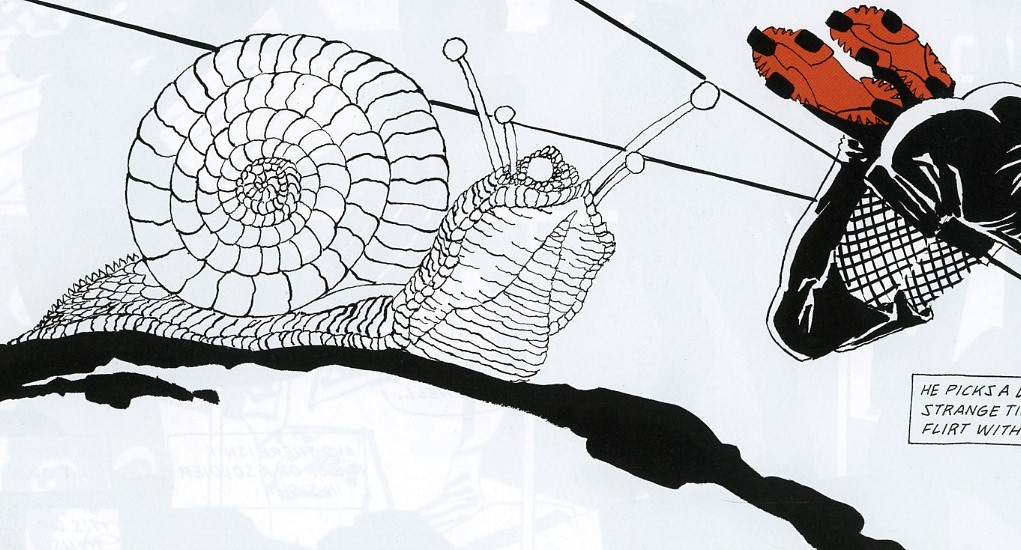

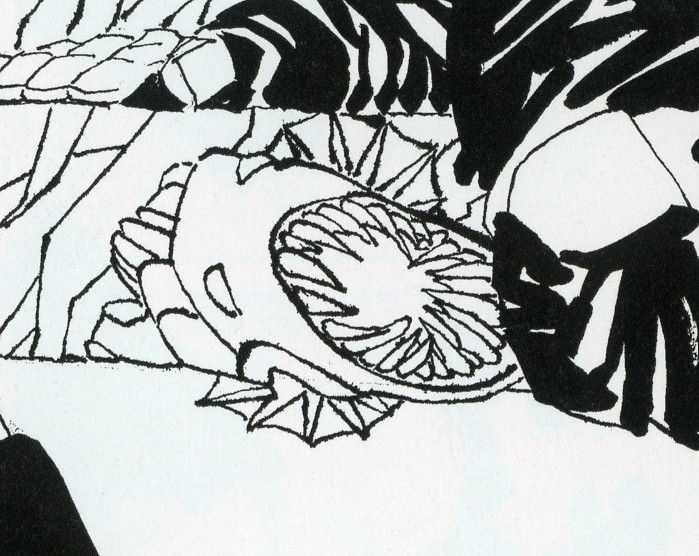

I actually like the second half much better, which does away with such painterly tricks (and which has been criticized, as a consequence, as Miller forgetting how to draw or not giving a damn anymore). And here we are getting to the fascinating part–because, well–there’s that snail. Huh? In the panel of Not-C deciding to go into the mosque, there is a beautifully drawn, purely built out of uninflected lines, snail–a giant snail, obviously, given the perspective of the drawing:

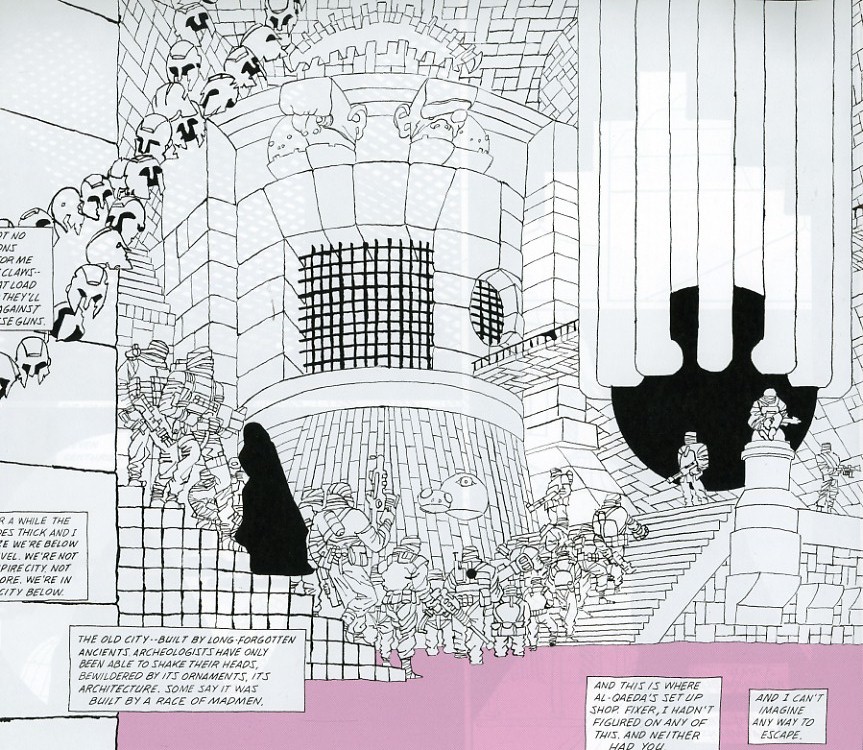

It is in no way given a narrative reason for being there. It just is. At this point, Miller enters a mode of strange narrative excess, going well beyond the requirements of the story–and he continues with it, the snail is not just a one-off. Look at the large, almost page-sized panel of the tower-like structure underground:

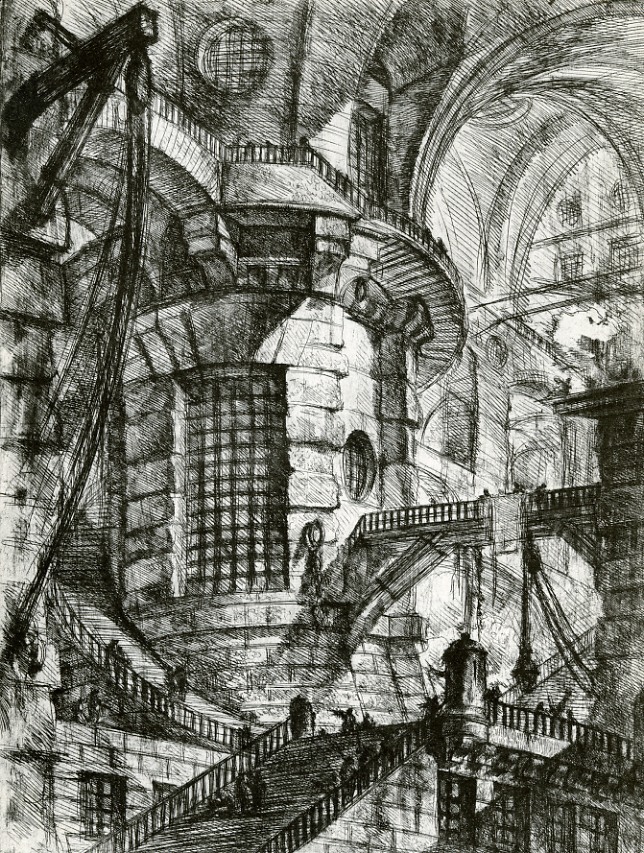

First of all, it’s important to realize it’s a swipe–from one of Piranesi’s “Carceri” (Miller at least gets points for creativity in swiping)–specifically this one:

Now, interestingly, this is not the first time that Piranesi has been swiped in comics recently–see the cover of the Act-I-Vate primer–but this is a much more, shall we call it, original kind of swiping. It’s also a much more interesting swiping than the one he practices in the first half of the book, where this panel of Not-C leaping off a building:

is clearly intended to evoke this famous image from “The Story of Gerhard Shnobble,” by Miller’s hero, Will Eisner:

The swipe from Eisner is clear fan-service, intended to give the thrill of recognition to the literate comics reader, and to help Miller claim for himself, one more time, Eisner’s mantle. I don’t think any such kind of knowing reference and recognition is intended with the Piranesi borrowing—it is not an homage, but neither is it done out of laziness or for simple convenience. The image is transformed, worked over too much for that to be the case. Look at the brackets holding up the tower’s cornice: In Miller, they have been replaced by symmetrical pairs of faces–one Gahan Wilson-like, the other best described as Humpty-Dumpty-as-dying-Vader:

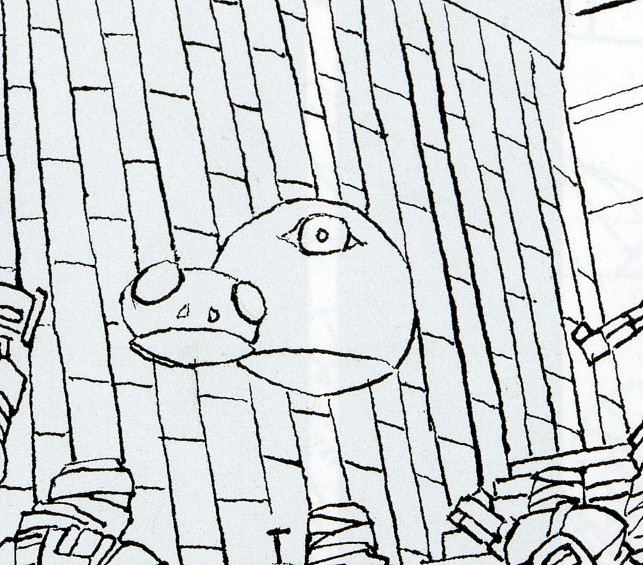

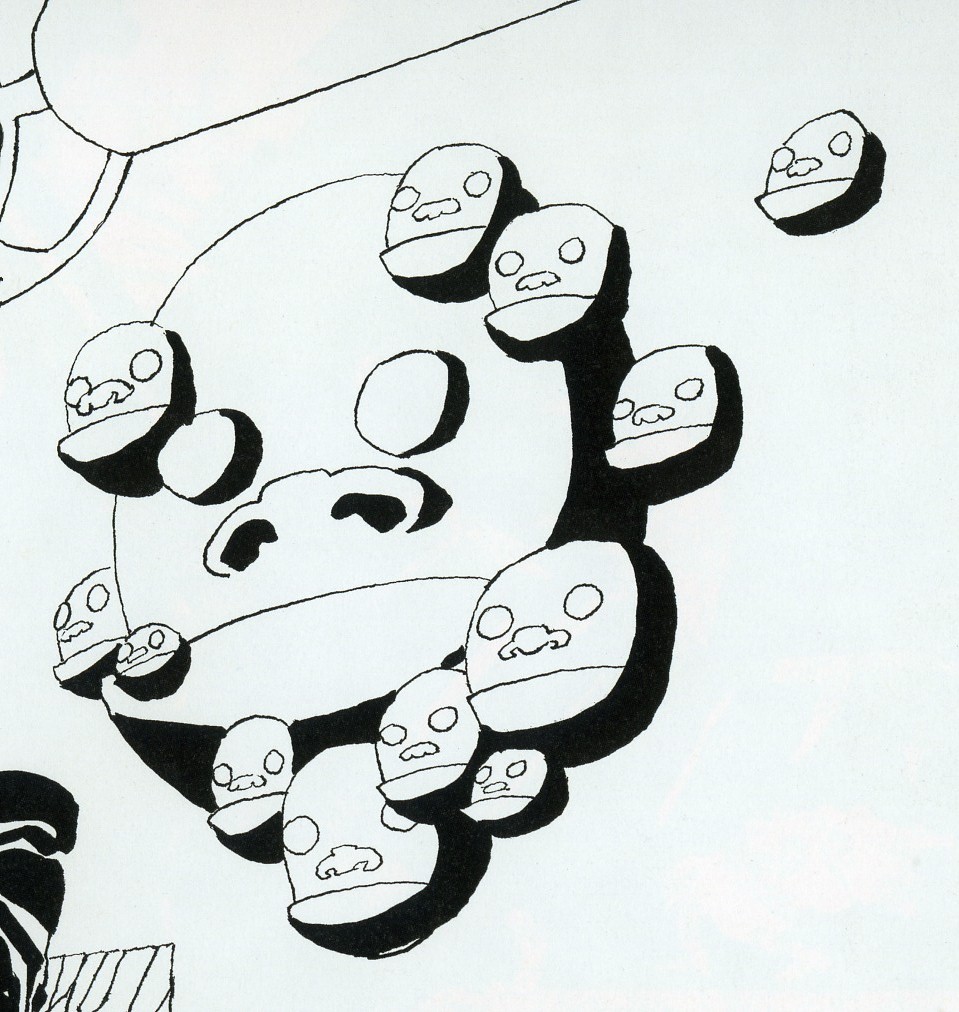

Again, what??? Then there are the strange ovoid faces toward the bottom of the tower:

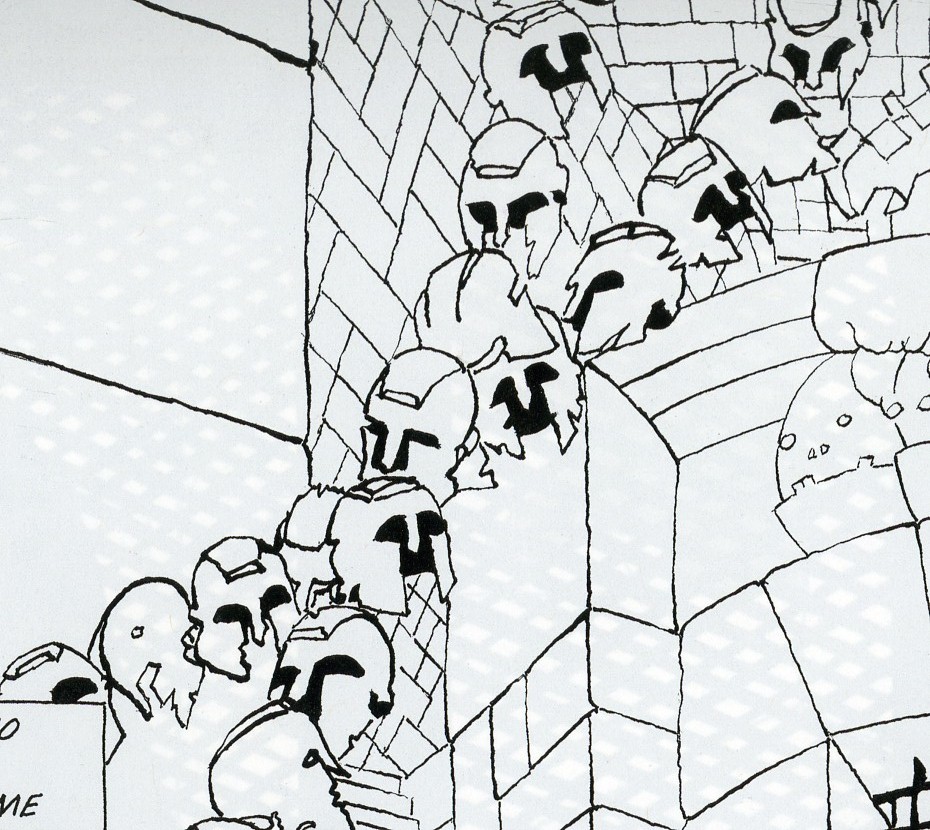

and the double garland of Spartan helmets festooned across the upper left corner of the panel:

Miller makes a gesture toward explanation in a caption (“The old city–built by long forgotten ancients. Archaeologists have only been able to shake their heads, bewildered by its ornaments. Some say it was built by a race of madmen”)–and, if in the context of the book, that seems like just a convenient excuse to doodle whatever he feels like in the images, it’s also strangely self-referential: yes, we too can only shake our heads, bewildered by the book’s ornaments which are completely unrelated to the book’s overt message. “A race of madmen”–and we almost feel that Miller’s gone nuts.

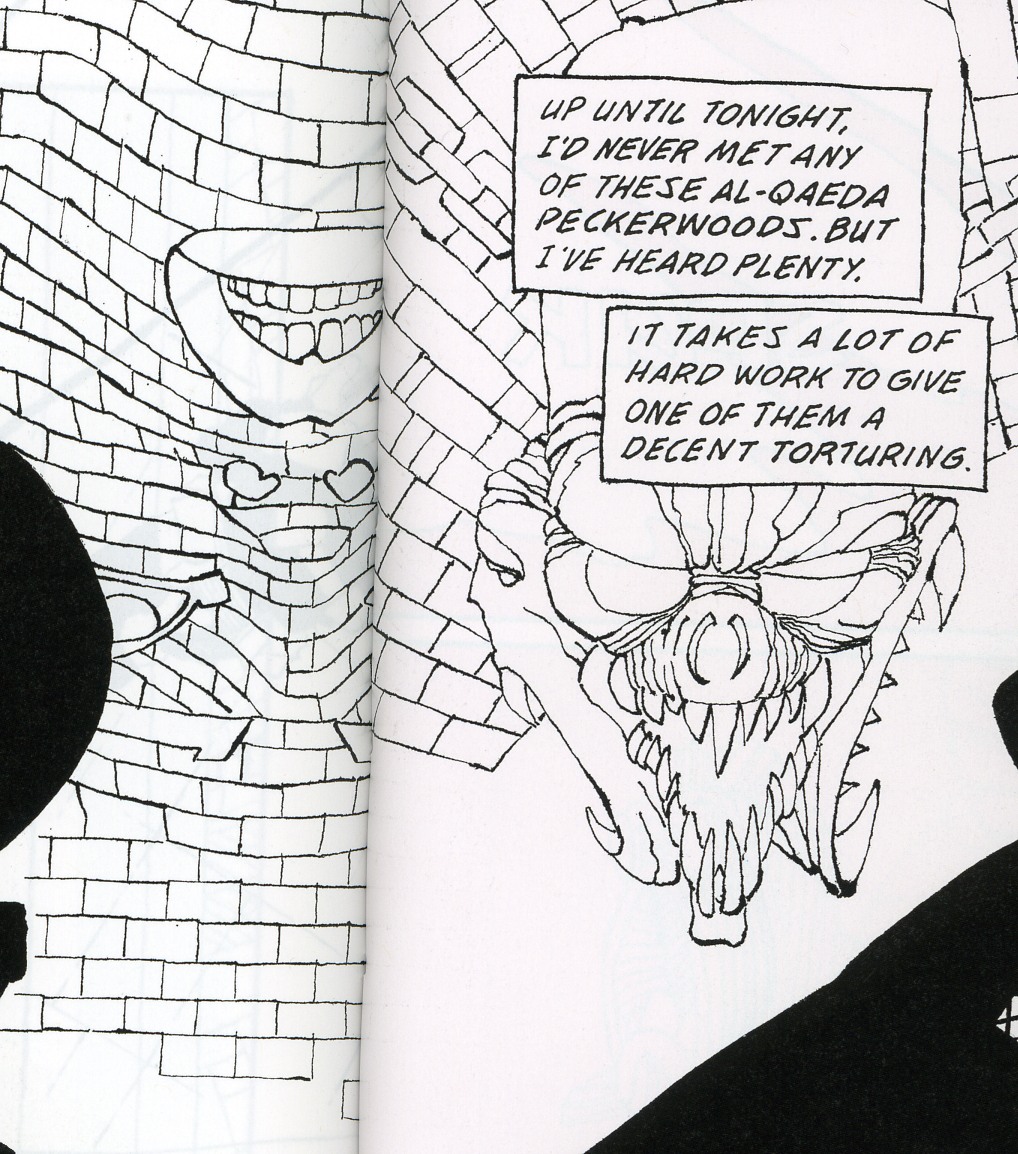

Then–then there are the strange Cheshire cat grins on the brick walls:

the gargoyles and dinosaurs sticking their heads out:

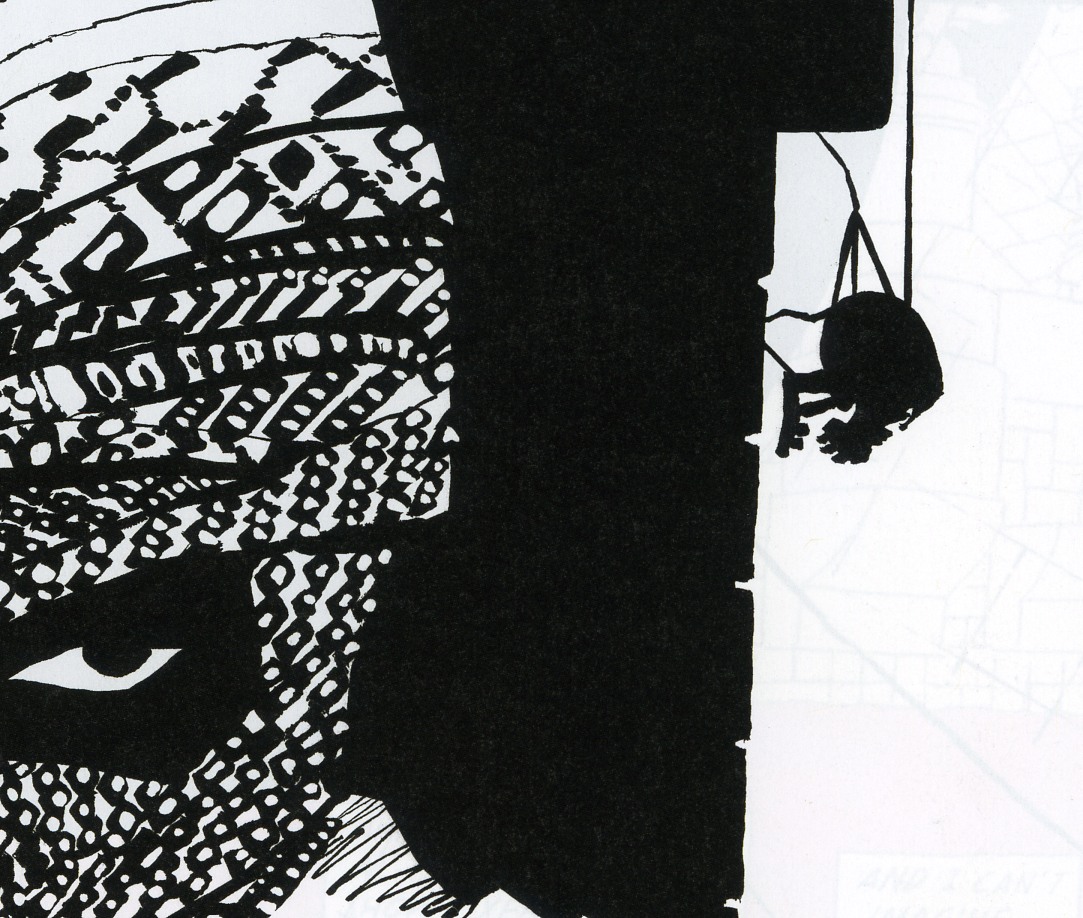

the strange silhouetted ball-with–feet-and-hands rappelling down the wall behind one of the terrorists:

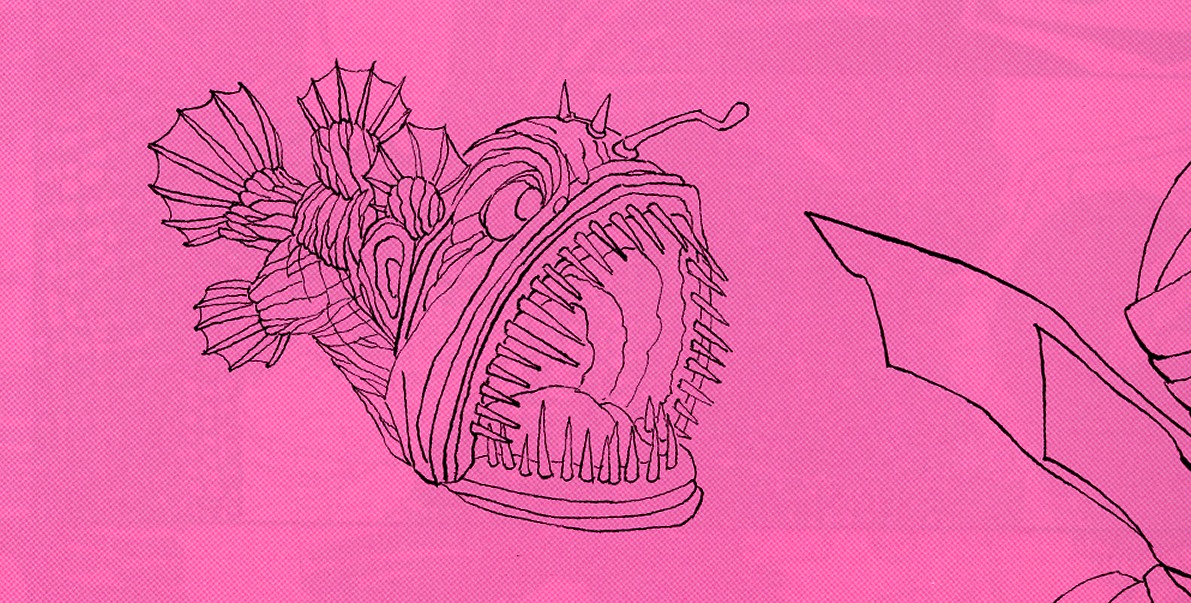

There’s the deep-ocean angler fish in the few feet of water into which Not-C jumps:

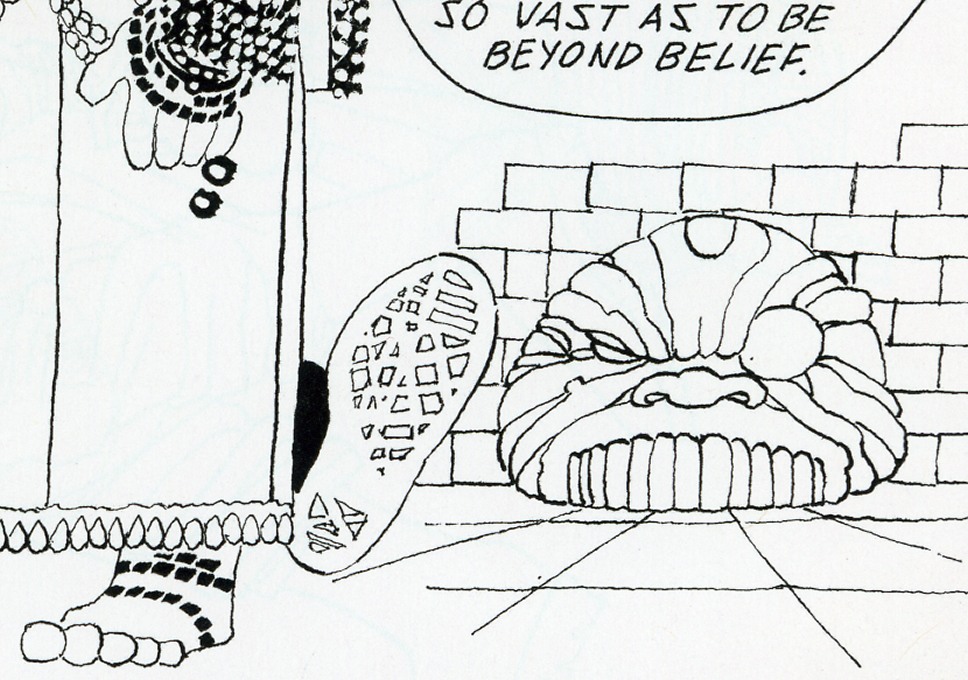

There’s the monocled Erich-von-Stroheim-in-The-Grand-Illusion half-face on the ground, behind the short veiled “highly-verbal” Persian-looking guy:

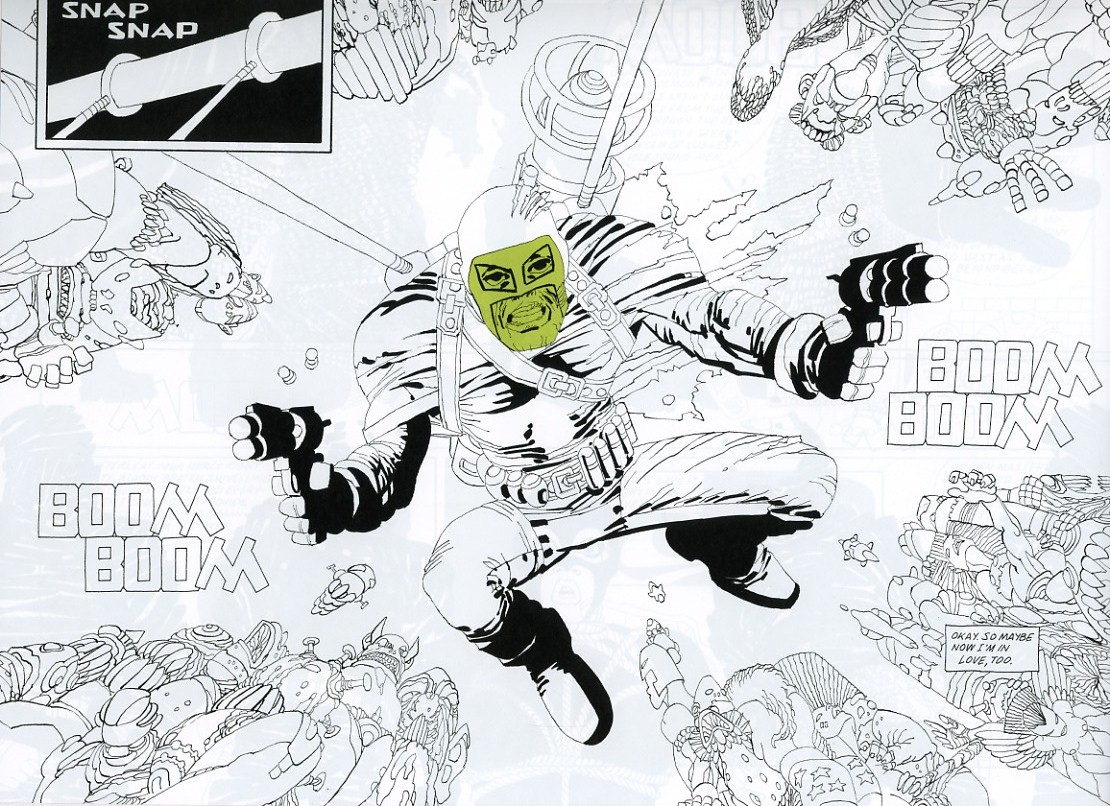

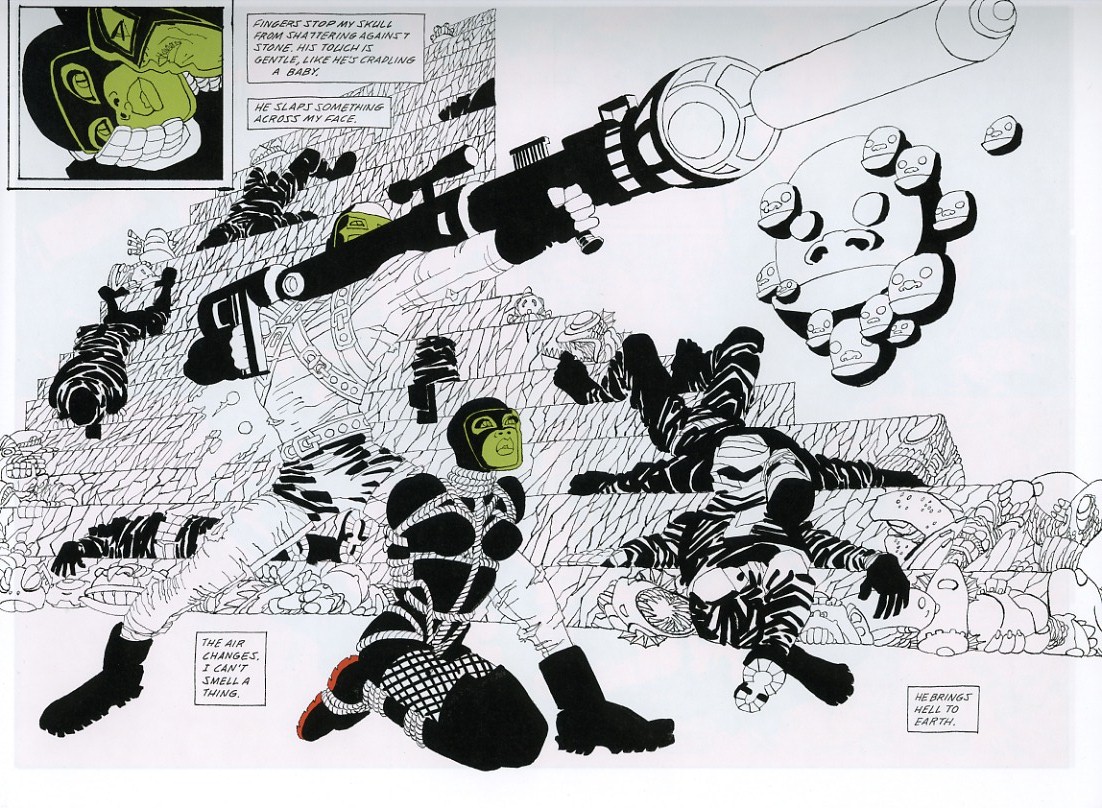

There are the Pop accumulations of figures, including a woman, from the back, in star-spangled hotpants and some kind of viking-monster, in the panel where Not-B leaps in:

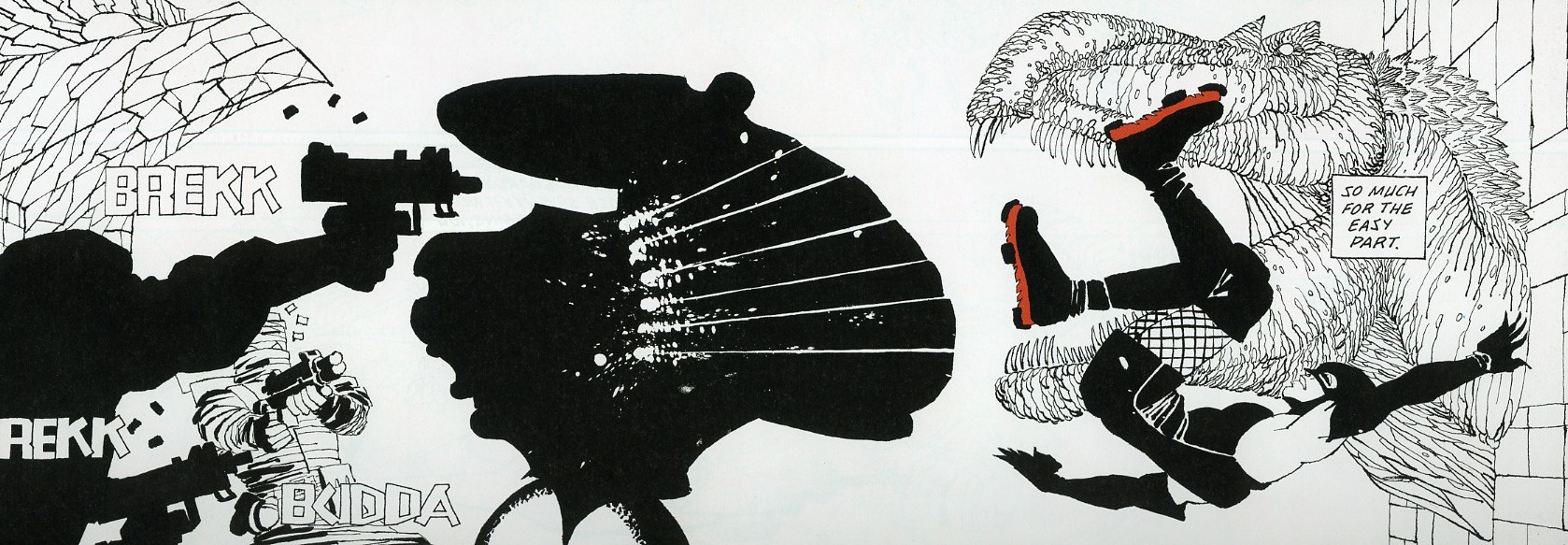

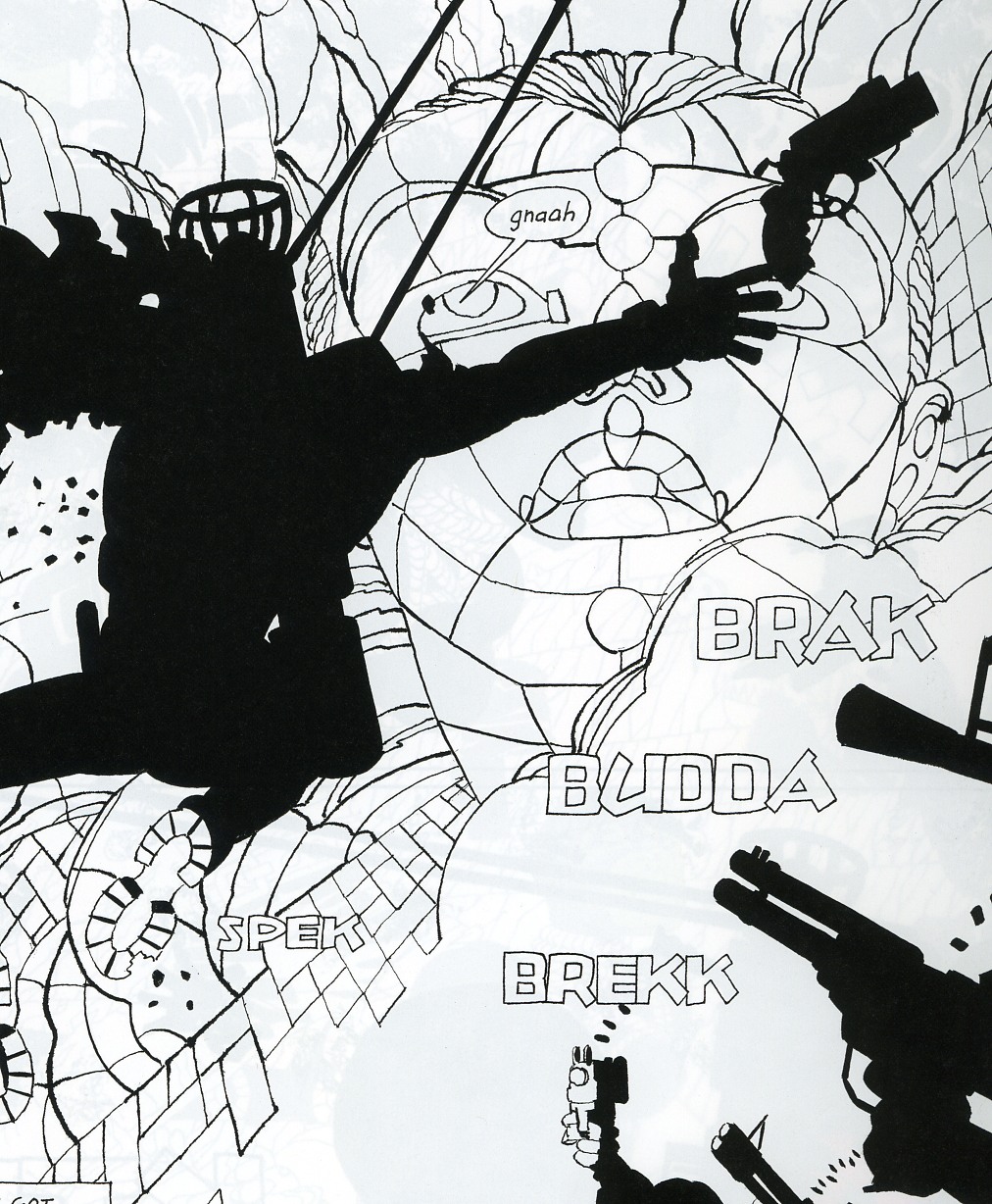

There is the monumental statue of Buddha (recalling Bamiyam? But again, why? If the Taliban blew it up there, why would Al Qaeda live with it here?) behind a sound effect of–har har–“Budda”:

There are all those accumulated faces and grins behind Not-B when he fires his bazooka thing:

… and so on.

There is, overall, a strange, unsettling kind of image excess over the requirements of the story. It’s as if Miller couldn’t stay faithful to his ideological convictions, or even his hatred of terrorists, and began doodling. Is it some kind of Baroque horror vacui, or–more appropriately, perhaps–some kind of outsider art horror vacui? At times, and mutatis mutandis, it almost reminds me of Rory Hayes. I like how at this point Miller’s mastery fails: the slick paintwork of the first half gives way to the red-background two-panel of Not-B and Not-C waiting for the bomb to explode, that looks so awkward, almost untaught, as to completely negate the slickness of the first half:

It’s a mad, bizarre book. I had hated Dark Knight Strikes Back, thinking Miller had gone crazy, but now I realize it’s just that he had not gone crazy enough. I have no idea where he can go next–but there is a strange breakthrough here (maybe with no exit, with nowhere to go) that is more interesting than any other comic I’ve read this year, and hinting at a kind of artistic madness that most artcomics can only aim toward, but not quite reach.

Whew. I’ll stop here.

And stop I did. After my rant, in response to a post by Charles Hatfield who declared himself so morally outraged by the book and by my discussion of it that he refused to engage it critically formally (even seemed to see it as immoral for anyone to do so), I responded:

Hey, Ken’s response to Holy Terror was much more positive than mine! Why is it mine that warrants this rant?

I’d be happy to explain, at length, what Miller’s work has meant to me over the last two and a half decades–in view of which, at least, he still does warrant my critical attention, whatever his current political positions. I’d also be happy to get into a discussion whether any artist’s political positions that you (or I, for that matter) may disagree with are enough to put their work beyond the pale of critical discussion (Ditko, anyone? T.S. Eliot? Ezra Pound? Seurat, for that matter, who had clear left-anarchist associations? Where do we draw the line?). But I’ll just say that I was addressing the work, not the man, and the work definitely does warrant such critical attention. And given that the work is intended to convey a certain political position, and that many of the elements I discussed actually end up undermining, deconstructing in some way, that position, I’d say it is exactly analyzing it in such “art terms” that can provide a constructive critical, and even political, perspective on the book.

(I’m quoting my response to provide some shield, some defense against similar critiques that may be raised. And, ok, maybe I’m being paranoid too, in a different way.)

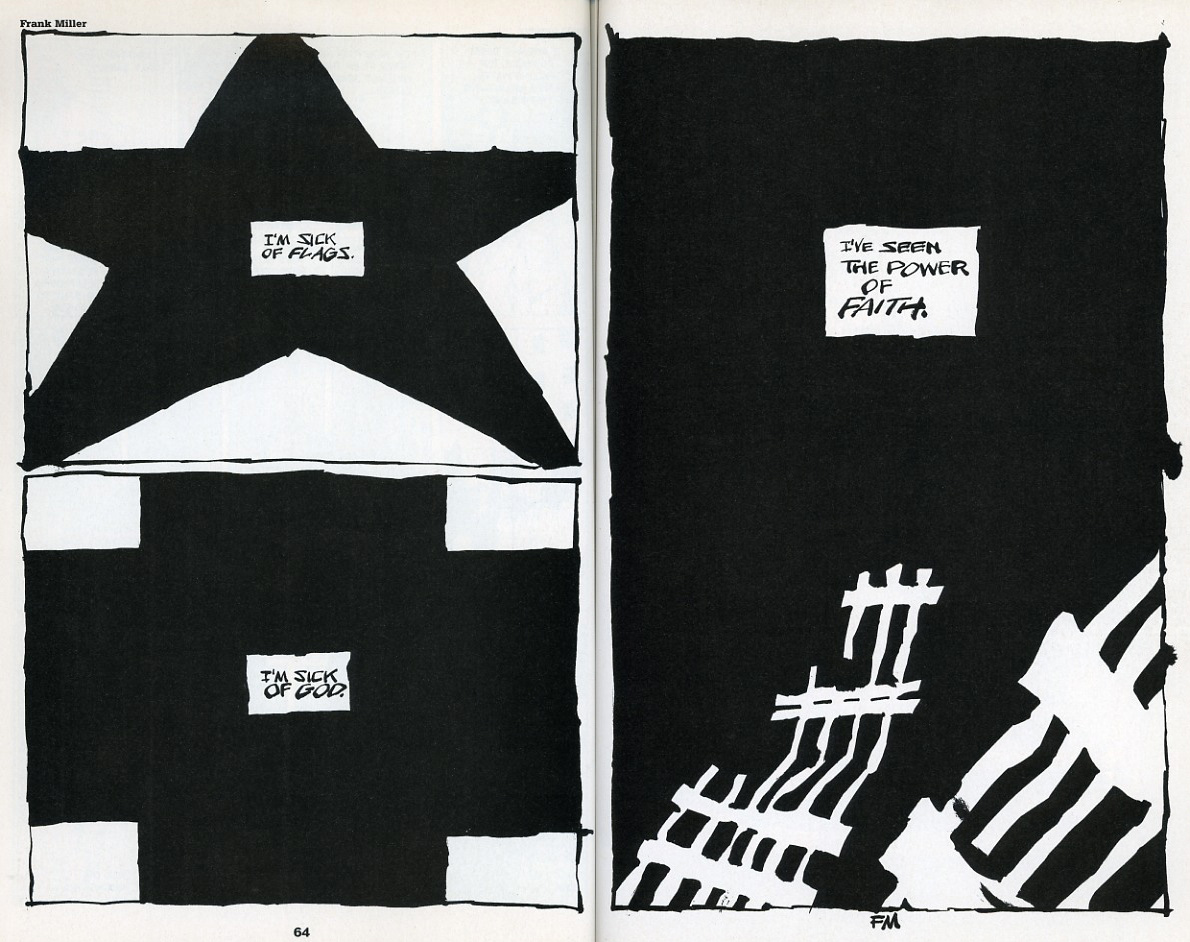

If I were to expand this and properly re-write it, I would emphasize further the strange self-consciousness of the book that I hinted at on one or two occasions: the apparently braided diegetic and non-diegetic strands (the only way it seems to me the book’s temporal contradictions can be resolved) and the comment about “the race of madmen.” Holy Terror feels like a strangely self-knowing book, but one that in the same gesture paradoxically foregrounds the lack of self-reflection on the part of the artist, the contradiction between the resulting work and its intended ideological functioning. I would also tone down my criticism of the rudimentary plot: it more and more seems to me that Miller’s abandonment of the (genre-based, admittedly, I say to preempt any griping) narrative sophistication of his ‘80s work is fully intentional; and the fascinating bizarreries I point out here would have been impossible had such sophistication not been abandoned. I would also compare the book to Miller’s contribution to 9/11: Artists Respond, which refreshingly rejected any and all ideologies:

(Homework assignment: what happened?)

Also, as I’ve been thinking a lot about Kirby lately, I can’t help but feel that the rhetoric of visual excess I use here to discuss Holy Terror is not all that different from what I and others have said to defend the King’s work of the seventies and after. I don’t know if that constitutes some kind of redemption for Miller; I don’t know if connecting the two in such a way is at all legitimate (I am only referring to my own rhetoric, which I do know is strangely similar)—but I know for a fact that my just bringing up the notion is sure to prompt yet another, additional, shitstorm in the comments. (James? Charles?) Have at it, all.

__________________

Editor’s note: Andrei writes more on Frank Miller at his own blog here.

I wanted to ask Andrei; you mention how important to you Miller is. I’m wondering if you feel like what you get out of Holy Terror is to some significant extent because of that? Would this have the same impact on you if it were by some random creator who was not Frank Miller?

For me…Miller’s always flirted with self-parody; his noir verging on the grotesque, especially in Elektra, which is maybe my favorite thing of his. I guess I’m also curious a to whether this makes you reassess his older work (not necessarily for the worse.)

Not Andrei but the older I am, the worse Miller reads. That said, I think this book is a spectacular, dazzling display of the craft of CARTOONING.

Shitty, evil little book, but wow!

Noah–I don’t think that what I get (positively) out of HT is influenced by my love of earlier Miller–if anything, it should be negative, as was my response to “Dark Knight Strikes Again.” At the time I expected it to somehow continue the feel of DKR, and was sorely disappointed. In a way, I had to learn to appreciate him completely differently to “get” HT, or at least get what I’m saying above. But, admittedly, if I hadn’t cared about Miller in the past, I might not have paid any attention to HT, so there’s that…

Do you mean the Elektra graphic novel that he drew? Yeah, I can see that move into self-parody. Though I think the pieces that mattered most to me–again, the Daredevil run, Born Again, DKR and Elektra Assassin (Year One being on a slightly lower rung)–didn’t play with self-parody yet. (Well, I guess you could say EA did, but only in the matter of writing, since he didn’t draw it.)

No, no; I meant Elektra Assassin. I totally think that and DK tilt into self-parody; the hard-boiled prose is so far over the top; it’s like Philip Marlowe on steroids and uppers and probably several other controlled substances as well. I love it, but it’s completely ridiculous — or rather I love it because it’s completely ridiculous. (And I think Sienkiewitz’s art works well in that regard as well….)

I kind of enjoyed DK2 in that way as well, I have to admit.

I’m not sure EA or DKR are intentional self-parody, though. The later stuff, later Sin City or DKSA, may be. I just couldn’t get past the color in DKSA, though. I tried to re-read it recently (in light of HT), but it just made my eyeballs burn.

I’m not sure whether it is self-parody, since his actual worldview seems to be based on Dirty Harry movies, Mike Hammer novels, and Batman comics. That came through especially with his line about how Al Queda is having a dark chuckle at the ridiculous antics of effete Occupy Wall Street hippies. I think Miller might actually see himself as kind of a macho, badass action hero at this point.

…a post by Charles Hatfield who declared himself so morally outraged by the book and by my discussion of it that he refused to engage it critically (even seemed to see it as immoral for anyone to do so)…

Andrei, this is a gross mis-characterization of what I said in my post, and I don’t like being set up as the bluenose/straw target here. I would never suggest that it is immoral to engage a work critically, and that is the opposite of what I intended.

For the record, here is what I said in the two posts I sent in reply to your original:

Miller’s best skills are graphic, and these are on view in HOLY TERROR. The messy ink-work has a certain slapdash energy, an explosiveness, that seems gutsty enough. Besides that, though, the book is a distillation of Miller’s personal cliches–a rifling-through of his private stock basket–and, basically, a kind of psychic vomitus. To present this kind of thrice-tilled garbage in a deluxe widescreen HC is hubris at its worst.

And the sequel:

Artistic madness, yes, and at times interesting, like a sputtering, skittering fuse.

BUT (fair warning: if you’re uninterested in critical swiping, as opposed to scholarship, bag out now!) Miller is not Rory Hayes. He’s a well-heeled, well-taken care of, sycophant-buffered millionaire cartoonist doodler blowing this stuff out his ass, with manifest contempt for both audience and craft, energized (if that’s the word) by a wholly unearned sense of being put upon and abandoned by a world he can now construe only in terms of hateful fantasy, a world that he has had all the tools and opportunities, affordances and privileges, needed to address, but which he can only distract with an upturned middle finger. He doesn’t warrant being taken seriously in the art terms you’re talking about, Andrei, because his sense of hurt and alienation is entirely unrooted in the kind of genuine, and revelatory, psychic distress that marks “outsider artists” like Hayes. Miller has at his disposal schooling, conventional intelligence, functionality, privilege, social acceptance, opportunity; he is not a Hayes or Darger.

And he is able to take these “stances,” i.e., to engage in this kind of odious, demagogic position-taking, because he is buffered, upheld, swaddled, wealthy, and living in an environment of extreme right-wing hate-mongering pseudo-journalism and punditry. Holy Terror is not a text I can evaluate independently of those factors. Like most Chick tracts, it is that thing we mean when we talk about “hate literature.”

From the way people talk about the “fascinating” trainwreck of Holy Terror, you’d think Miller were an obscure genius savant living in a cell somewhere. He’s not. He’s a well-fed button-masher with a platform, one he uses to vent because he can. Ugh, gimme a break.

At no point does this admitted screed ever say that it is immoral to engage Miller critically. Rather, it engages Miller critically from a different perspective, one that is frankly moralistic but, from my view of things, warranted by Miller’s political posturing.

I did not “refuse to engage it critically.” I engaged critically on moral and ideological grounds. Your words above mistake, or mis-characterize, my censure of the work as a call for censorship of its discussion. The distinction may seem too fine-grained to bother with, but to me it’s absolutely crucial.

For the record, I was not responding only to your post, but to a general tendency I’ve seen in discussion of Miller (and of other comics creators as well) to discount the rancid position-taking of the work in favor of an aestheticization that reabsorbs the work into comics fan discourse, all sins forgiven, all doubts absolved, resolved, and defused. It was unfair of me to unload on your post in response to this much larger trend (call it the Chick/Ditko/Sim Syndrome) of refusing to engage the manifest ideological content of comics; obviously, my response was based on cumulative frustration.

Case in point: Shitty, evil little book, but wow! What are we supposed to do with that kind of compromised stance? Are we supposed to do anything? Let our jaws unhinge out of admiration for craft divorced from content, ideation, intention, moral stance, point, purpose? Are we supposed to thrill at Miller’s wandering, doodling pen because even he can’t sustain faith in his project? If I call the thing as I see it, is that too a form of engaging critically?

My beef is this: don’t caricature my points. If you want to use ’em, use ’em, but don’t set me up in the a bluenose/censor/preacher role without letting my words speak. Comics fans instinctively hate bluenose/censor/preachers, and slotting me into that role, sans the context, is dirty pool. Give me a chance to show your readers what an ass I am in my own words; don’t act as if I’m trying to hinder discussion of a text.

This is an ironic turn of events for me, given my rep as a formalist/aesthetician at heart!

I liked DKSA, actually, for similar reasons. It’s just so crazy and over-the-top (and has almost no relation to DKR)… Haven’t read Holy Terror, so can’t comment on that…though the snail and some of the other odd doodles in the post certainly piqued my interest where I had none previously.

I liked the analogy of this work to the late Kirby—loud, powerful, messy, incoherent— That makes sense to me.

The problem with the analogy is, of course, political. Kirby’s politics are more congenial to most of us (or innocuous enough not to pay attention). Obviously, any engagement with Holy Terror has to begin with the requisite disdain for its politics—and a near avoidance of its narrative…which is often hard to do in a genre that is often narrative in orientation.

Something like DKSA has problematic politics too…but it’s somewhat buried in all the conventions of superhero genre stuff and familiar characters blowing each other up. When a book is explicitly Muslim-hating and is set up as some kind of weird one-man war on “terror,” it’s harder to ignore.

I wonder what you think of the Martha Washington stories (written by Miller, art by Dave Gibbons–for those not in the loop), Andrei. I read them fairly recently and they kind of make me queasy.

I wasn’t really suggesting the self-parody was exactly intentional.

Charles, thanks for posting those comments. I actually agree with you in general that ideological content is something for critics to take into account, and that the tendency in comics circles to forgive all on the basis of craft can be a problem.

I think I disagree with you on two points. First, I think the issue of how much money or success Miller has is largely irrelevant to the question of whether he can be talked about in art terms. In fact, I don’t really know why or how it would be verboten to talk about somebody in art terms. He made a work of art, right? That work of art can be ideologically repulsive and be fascinating in terms of its inspired messiness, telling lapses, or some other factor. The issue isn’t whether one’s allowed to appreciate any aspect of it, or whether you can talk about craft *or* ideology — rather, it seems like the point is to create a reading which includes or thinks through one’s aesthetic experience, which includes both elements of craft and elements of ideology and how they are tied together. (I could talk at some length about why I find D. H. Lawrence’s misogyny practically the most interesting and compelling aspect of his work, while Yeats’ misogyny is inextricable from his lyricism and yet simultaneously for me mars it…and so forth.)

The other thing I disagree with you about is that Andrei is definitely opting for craft over ideology in his reading. It’s somewhat sketchy, since it’s a quick response rather than a finished piece, but he mentions the possibility that the madness here could in some ways push back against the ideology….and isn’t the ideology part of the madness? It seems like you could go various places from here, many of which don’t necessarily involve just marveling at the artwork, or even evaluating the whole work as especially positive.

Just a last point about not quoting you — the listserve is semi-private, so I think there’s dicey etiquette around quoting somebody from there without permission. Probably I should have just asked you if we could quote you, and I didn’t simply because it didn’t occur to me. My apologies for that.

In fact, I don’t really know why or how it would be verboten to talk about somebody in art terms. He made a work of art, right?

Thanks, Noah. Yes, you’re right: it cannot be verboten to talk about something in art terms, and to the extent that I suggested it could be, I was overstepping.

What I was trying to say is that I don’t regard the aesthetic as the most compelling POV from which to discuss Holy Terror.

Andrei is doing interesting work here insofar as he is reading Miller against the grain of his express intentions (the madness here could in some ways push back against the ideology…), but I find myself still too caught up in the backdraft from Miller’s political ranting to be able to afford the work the patient, indulgent reading required to bring such tension to the surface.

So, I suppose I should be thanking Andrei for doing that work. :-|

I’m glad you brought up the issue of etiquette. It’s true that I would not have wanted to be quoted publicly without a prior consultation. But nor would I have wanted to impede Andrei’s work.

It’s just that Andrei’s characterization casts me in the role of censorious bluenose, which not only misjudges my values and mischaracterizes what I’m asking for, but also sets me up to take a role that, in the comics blogosphere, is worse than thankless.

Yeah, I’ve gotten to be the bluenose on occasion. It’s not exactly thankless, at least not for me…I think comics could use a few more Puritans.

But that could just be me being contrarian.

I’m sure Andrei’ll be back to respond; I know he’s been quite busy.

I was glad to read this just to get a look at some of the art from the second half of the book. This stuff is demented.

I flipped through the first couple of pages at my local comics shoppe and found them so aesthetically offensive I couldn’t even look at them too closely. The arbitrary brush splatter that doesn’t correspond to any environment or mimic a texture is an amateur hack move I usually see perpetrated by… comic book students trying to imitate Frank Miller. I think self-parody implies too much agency on Miller’s part. More like he’s disappeared so far up his own butthole he doesn’t really think too carefully about anything he thinks, says or draws.

But that’s a cool snail.

Well, that might have been unfair. He’s thinking about what he draws. As a draftsman he’s on another level. But damn, girl I have no patience for those ink splatters.

Charles–I’m sorry that you’re so upset, but (maybe mistakenly), I thought that my “seemed to see it as immoral for anyone to do so” was a pretty fair paraphrase of your “he doesn’t warrant being taken seriously in the art terms you’re talking about, Andrei,” especially given that supporting that was your self-described “critical swiping,” which I don’t think I’m wrong in describing as morally outraged at his being a “well-heeled, well-taken care of, sycophant-buffered millionaire cartoonist doodler blowing this stuff out his ass,” at his “hateful fantasy,” etc. My mistake was in saying that you “refused to engage it critically” (and saw it as immoral, etc). I should have said you “refused to engage it aesthetically,” or “formally.” That is a pretty direct translation of your claim that “Holy Terror is not a text [you] can evaluate independently of those factors”–specifically of the factors of his “odious, demagogic position-taking, because he is buffered, upheld, swaddled, wealthy, and living in an environment of extreme right-wing hate-mongering pseudo-journalism and punditry.”

Am I wrong? are “odious,” “hateful,” “hate-mongering” anything but moral judgments? Isn’t it those moral judgments that prevent you from otherwise engaging the work?

Anyway, if you think my use of “critically” instead of “formally” is enough to warrant your description of my words as “a gross mis-characterization” and “set[ting you] up in the a bluenose/censor/preacher role without letting [your] words speak,” then I apologize.

Also, I really have no truck with your imputing a ” genuine, and revelatory, psychic distress” to Hayes or Darger that you refuse Miller because he “has at his disposal schooling, conventional intelligence, functionality, privilege, social acceptance, opportunity.” That is a very slippery slope to go on. It’s pretty much impossible to know anyone’s “psychic distress” (not that I suggested, or ever would, that Miller has such a thing), but to see some as more genuine than other–because, largely, you don’t think that other’s social position makes such genuineness possible–is rather troubling. Last I checked, “psychic distress” can affect all social strata indiscriminately. Also, from my point of view, outsider art doesn’t need “psychic distress” to function, Hayes’s work functions perfectly well without having to be explained by “psychic distress” (I have long appreciated it aesthetically without knowing anything about his psychological state), and while Darger’s work does need some kind of psychiatric explanation, for me that actually makes it not genuine, but troubling and really an aesthetic failure. (I know I may be in the minority on this one.)

After the comixscholars thread you sent me a much more measured response, which I appreciated it. Why don’t you repost that one–I think that one could help to carry this discussion forward.

Eric–again, not engaging them politically, because I haven’t read them recently and in enough detail to be able to say (I read the first series, and skimmed the rest), the Martha Washington stories was kind of where I started jumping off the Miller bandwagon. They do, if I remember, have a kind of libertarian stance that could be interpreted both negatively and positively, but I honestly wouldn’t be doing them justice if I discussed that without re-reading them. What I do remember is that it basically started as a Halo Jones swipe, and ended (the entire cycle, I mean) as a kind of 2001/Tron swipe–well, except for that last issue set like a hundred years later, which was kind of a Terminator swipe–and pretty much everything in between was patched from very obvious sources, a kind of collage without much creativity in the patching together.

Charles, I changed “critically” to “formally,” above, but left “critically” under erasure so that people can see what we’re talking about.

[edited–never mind.]

Slightly off topic, but isn’t there a literary term for something in a story that’s part of the story but the characters don’t interact with it and its not necessarily supposed to be taken as present in the physical sense, like a Greek chorus or the nonsensical wacky fish in the background of a Batman comic?

I seem to recall reading there’s an academic term for a non interactive story element but I can’t recall what it is.

I’m trying to decide whether it turns out the best way to actually avoid a shitstorm in the comments is to a) predict it, or b) try to answer all objections in the text itself (since I’ve done both).

In any case, I meant to add something of which I had thought before writing the original version of this piece, but which then somehow slipped my mind. The combination of Islamic setting, gigantic architecture, descent underground (the Al Qaeda lair in “Holy Terror” is supposed to be a mile underneath the city) and the sublime (including the Piranesi source) reminded me a lot of William Beckford (him of the Fonthill Abbey Gothic folly, the attempt to build the tallest building in Great Britain at the time) and his amazing novel, “Vathek” (1786), and specifically of the descent of Vathek and his beloved Nouronihar into hell, via an endless staircase. (See here: http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Vathek/Vathek) Here are some excerpts. Note also the “capitals, of an architecture unknown in the records of the earth”; the stone animals and the “figures.. embossed” in the walls of the palace; the underground vaults; etc.

…………………………………….

“A death-like stillness reigned over the mountain and through the air; the moon dilated on a vast platform the shades of the lofty columns, which reached from the terrace almost to the clouds; the gloomy watch-towers, whose numbers could not be counted, were veiled by no roof, and their capitals, of an architecture unknown in the records of the earth, served as an asylum for the birds of darkness, which, alarmed at the approach of such visitants, fled away croaking.

The chief of the eunuchs, trembling with fear, besought Vathek that a fire might be kindled.

“No!” replied he, “there is no time left to think of such trifles; abide where thou art, and expect my commands.”

Having thus spoken, he presented his hand to Nouronihar, and, ascending the steps of a vast staircase, reached the terrace, which was flagged with squares of marble, and resembled a smooth expanse of water, upon whose surface not a leaf ever dared to vegetate; on the right rose the watch-towers, ranged before the ruins of an immense palace, whose walls were embossed with various figures; in front stood forth the colossal forms of four creatures, composed of the leopard and the griffin; and, though but of stone, inspired emotions of terror; near these were distinguished by the splendour of the moon, which streamed full on the place, characters like those on the sabres of the Giaour, that possessed the same virtue of changing every moment; these, after vacillating for some time, at last fixed in Arabic letters, and prescribed to the Caliph the following words:

“Vathek! thou hast violated the conditions of my parchment, and deservest to be sent back; but, in favour to thy companion, and as the meed for what thou hast done to obtain it, EBLIS permitteth that the portal of his palace shall be opened, and the subterranean fire will receive thee into the number of its adorers.”

He scarcely had read these words before the mountain against which the terrace was reared trembled, and the watch-towers were ready to topple headlong upon them; the rock yawned, and disclosed within it a staircase of polished marble that seemed to approach the abyss; upon each stair were planted two large torches, like those Nouronihar had seen in her vision, the camphorated vapour ascending from which gathered into a cloud under the hollow of the vault.

This appearance, instead of terrifying, gave new courage to the daughter of Fakreddin. Scarcely deigning to bid adieu to the moon and the firmament, she abandoned without hesitation the pure atmosphere to plunge into these infernal exhalations. The gait of those impious personages was haughty and determined; as they descended by the effulgence of the torches they gazed on each other with mutual admiration, and both appeared so resplendent, that they already esteemed themselves spiritual Intelligences; the only circumstance that perplexed them was their not arriving at the bottom of the stairs; on hastening their descent with an ardent impetuosity, they felt their steps accelerated to such a degree, that they seemed not walking, but falling from a precipice. Their progress, however, was at length impeded by a vast portal of ebony, which the Caliph without difficulty recognised; here the Giaour awaited them with the key in his hand.

“Ye are welcome,” said he to them, with a ghastly smile, “in spite of Mahomet and all his dependants. I will now admit you into that palace where you have so highly merited a place.”

Whilst he was uttering these words he touched the enamelled lock with his key, and the doors at once expanded, with a noise still louder than the thunder of mountains, and as suddenly recoiled the moment they had entered.

The Caliph and Nouronihar beheld each other with amazement, at finding themselves in a place which, though roofed with a vaulted ceiling, was so spacious and lofty that at first they took it for an immeasurable plain. But their eyes at length growing familiar to the grandeur of the objects at hand, they extended their view to those at a distance, and discovered rows of columns and arcades, which gradually diminished till they terminated in a point, radiant as the sun when he darts his last beams athwart the ocean…”

…………………………………………..

pallas, if you can figure out what that term is, I’d love to learn it.

Pallas, in film studies, the word to describe the world that the characters inhabit is the diegesis, so an element that they don’t see or hear is called “non-diegetic.” The most common non-diegetic element in movies is background music, heard by the audience, but not by the characters on the screen…

Is “non-diegetic” the term you’re looking for?

I don’t think that’s quite what Pallas is referring to, Craig. I think it’s a matter of finding a term for all those strange dinosaur heads and faces and creatures that, as far as we can tell, are diegetic to the world of “Holy Terror,” but not noticed or interacted with by anybody.

Also–what “nonsensical wacky fish in the background of a Batman comic”??? I want to hear more about this! Is there a “nonsensical wacky fish” in the Batcave, maybe?

After the comixscholars thread you sent me a much more measured response, which I appreciated it. Why don’t you repost that one–I think that one could help to carry this discussion forward.

Andrei, I find it more than a little galling that, after misrepresenting Charles’s views (without even citing them so readers could judge them for themselves), you’re now setting yourself up as the arbiter of “measured responses” who wants to “help to carry this discussion forward.” You just committed a foul; you don’t get to pretend to be the referee now.

I also think you’re still misreading Charles’s comments, even after he’s reposted them for all to see. I took the phrase “He doesn’t warrant being taken seriously in the art terms you’re talking about” to refer specifically to those terms you had just put forward, to treating Miller as an outsider artist (and using that label to overlook the political or ideological dimensions of his work), not to refer to any criticism of Holy Terror, full stop.

You also seem to think you’ve caught him in a rhetorical bind when you point out that he makes moral judgments (“Am I wrong? are “odious,” “hateful,” “hate-mongering” anything but moral judgments?”) even though he admits that these judgments are “frankly moralistic” and that he engaged Miller “critically on moral and ideological grounds.” None of that is equivalent to saying it’s immoral to discuss Holy Terror–quite the opposite. (It does suggest it’s immoral to give Miller a pass for his ideology by shoving him into the role of the outsider artist or by considering his art in isolation from his politics, but those positions can hardly be confused with shutting down discussion.)

I’m not sure why Charles (or anyone else) would have any interest in carrying this conversation forward when they are so repeatedly, persistently, doggedly misrepresented.

Marc–Charles and I have worked this all out in private, and I doubt he needs you to carry on a flame war on his behalf, especially in such a hyperventilating tone.

On a bit of a tangent, and maybe in hopes of making things a little less flamey…I think the outsider art question is pretty interesting in comics, precisely because it has a central role in the development of the field in a way that makes it not actually be outsider art in the way that it’s recognized in visual art.

That’s may be a bit garbled… What I mean is that people like Jack Kirby, and Crumb and perhaps Frank Miller and Marston/Peter and Alan Moore and Grant Morrison in some ways could all be seen as cranks or as untrained and as coming to the art establishment from outside, or from sideways. Maybe it’s partially because comics is something of a marginal form? In any case, I think there’s definitely an extent to which “genre hackwork” in comics can look like outsider art in certain instances with little more than a shift of perspective.

It’s hard to know whether that’s exactly a good thing; outsider art as a concept has a lot of problems. But I think you might be able to talk about those problems in interesting ways by looking at Frank Miller and the way his ideology is not divorced from, say, Fletcher Hanks’….

Andrei: This reads so much better with the images included. Seeing the giant snail and statue of a woman in start-spangled hot pants makes it that much more real. Though I suspect for me this would be a case of the imagery being much more interesting out of context.

[I’m just going to sidestep the ideology.] What strikes me most of all here is the use of color (love those odd fields of pink and puke green). Historically, comics so often stick to black and white or four-color/full-color (depending on the time period) that this odd use of a variety of spot colors looks almost revolutionary in itself. From an economic standpoint, I’d suspect most wouldn’t want to pay for full color printing and then barely use it. But visually it is striking.

Ok, I guess the term I was sort of thinking of is non-diegetic. (And I see Andrei used the term extra-diegetical in the article above)

I haven’t read this Miller book, but what this article reminded me of is some anime and cinema where there isn’t a consistent reality to the story, and there can be a blur between what is symbolic and real, or something can be symbolic and “not there” most of the time except a character may occasionally interact with or acknowledge the symbolism.

I tried googling “non- diegetic” and could find little discussing this unrelated to sound.

One thing I did find in google books was an article in “Quality TV” which discusses what the author calls “Dream diegeses”

Discussing Six Feet Under the google book excerpt that popped up in my browser said “In Yet another manifestation of dream diegeses, dead characters or character’s past selves appear and interact in the present with live characters in a manner reminiscent of modernist theater.”

It goes on to state Alan Ball stated the ghosts in the show “are not Ghosts per see but rather ‘A dramatic technique we use to portray the internal dialogue of the character”

From what I recall Will Eisner played with this sort of thing on occasion, I seem to recall reading a Spirit story with woman playing the piano who isn’t really “there” and is is a narrative device, but sometimes the characters acknowledge her?

But anyway the shift in art described above (just “inking treatment”?) seems to me to evoke this sort of “dream- diegetic” technique even if Miller wasn’t doing it intentionally.

There’s some anime directors who will play intentionally with art style and symbolism as a sort of magical realism technique, though I doesn’t sound like Miller can be doing it intentionally here.

I’ve flipped through “Holy Terror” a couple of time at the comics store. For all its idiocies, there are some interesting graphic effects going on there.

One I found particularly striking was how, in the immediate aftermath of the big terrorist attack, Miller draws a page with a few (4?) big rectangles. The next has many more, smaller rectangles; the following, a mass of tiny rectangles. Which, somehow — to me, anyway — suggests a multiplication of victims; the shattering of the giant structures that had been attacked into rubble. In a weirdly symbolic, almost-abstract fashion, more unnervingly powerful than a literal description.

Re those fascinating figures in the backgrounds of panels, a few arguably parts of the “race of madmen” architecture, most clearly not…

…I consider them symbolic analogues to the main characters and action. We see grotesquely distorted, sub-human figures; heroes and warriors, victimized women, villainous creatures; the story’s conflict echoed by primally ferocious-looking creatures like the anglerfish, T-Rex… (Though that snail — hardly gigantic in that panel excerpt, rather simply looming large in the foreground — is a baffler.)

Are these something like Plato’s Forms? Where…

——————————-

The objects that are seen, according to Plato, are not real, but literally mimic the real Forms. In the allegory of the cave expressed in Republic, the things that are ordinarily perceived in the world are characterized as shadows of the real things, which are not perceived directly. That which the observer understands when he views the world mimics the archetypes of the many types and properties (that is, of universals) of things observed…

——————————–

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Theory_of_Forms

Glancing down the Wikipedia article, saw this bit:

——————————–

He supposed that the object was essentially or “really” the Form and that the phenomena were mere shadows mimicking the Form; that is, momentary portrayals of the Form under different circumstances.

——————————–

Hmm! More of a coincidence, fortuitous graphic choices (the effects aren’t consistently deployed), but a times Miller renders the protagonists (in the “Budda” panel, for instance) as silhouettes, virtual shadows. While those “not there” Form figures are shadowless, pure line, suggesting their “purity,” detachment from the material world of physical solidity (the contrast emphasized in the “panel where Not-B leaps in”…).

I can’t recall the exact instances, but some comics or movies have featured sequences where the creators switch back and forth from, say, the hero fighting the villain, and a hawk battling a snake. That’s an effect, in a less obvious fashion, that I think Miller is employing here.

(Who was the cartoonist who had a series where characters would pose in the foreground while their shadows, cast on a wall behind them, would express their real self? I.e., while a pious-looking preacher wields a Bible, his shadow is lustfully grasping after the young hottie before him.)

Not exactly the same thing, but just remembered how Alfred Hitchcock set climactic hero-and-villain confrontations against Mount Rushmore (North by Northwest) and the Statue of Liberty (Saboteur)…

Derik: “This reads so much better with the images included. … Though I suspect for me this would be a case of the imagery being much more interesting out of context.”

Well, couldn’t one argue that discussing the plot (as much of it as there is) outside of discussing this imagery is equally out of context? If we privilege the plot as the main meaning of the story, and such “imagery” as subsidiary, we are already subscribing to a classical notion of what a text is–something that is challenged, say, by both James Joyce and Gary Panter. I’m not saying that Miller is intentionally aligning himself with such a sensibility–probably quite the opposite–but the comic, as it were, through the little attention paid to classic plot mechanics, and through the overemphasis of “subsidiary” imagery (for theory heads, we can even call it “parergonal” imagery), ends up requiring such a reading at least as a possibility, ends up divorcing itself from what a classically-conceived comics text is supposed to be. (See my older posts on “the logic of illustration,” to which most of Miller’s ’80s books subscribe, and often brilliantly so).

The emphasis on such subsidiary imagery is an important part of contemporary critical theory; for Derrida, that is often how a deconstruction begins, and also look at Barthes’ interest in details (the “punctum,” for example), or, for that matter–inspired by Barthes–Naomi Schor’s “Reading in Detail.”

Pallas–what you’re describing there is still pretty much all diegetic (or, to be more emphatic, “intradiegetic”)–that is, the character’s dreams still belong to the world of the story. “Extradiegetic” or “non-diegetic” is, say, the gutters of the comic, or Stan Lee addressing the reader directly.

But I actually think what you started pointing out was perhaps even more interesting than this diegetic/non-diegetic dichotomy, and something worth investigating further. Not quite the same thing, but I remember, when I took a theater directing class in college, a story the professor told us about a production he had seen, I think at the Yale Rep. I *think* it was a production of “The Brothers Karamazov” or “Crime and Punishment” or something like that. Basically, being a modernist adaptation, the play changed scenes without lowering the curtain, with stage hands dressed in black coming on the open stage and moving flats around, etc., between scenes. But after a while, to the audience’s surprise, the stage hands started interacting with the characters on stage, started showing up during the scenes, in the background, and not just in between them, and finally when a character commited suicide they prepared the noose and handed it to him…

So it wasn’t so much the story going into an extra-diegetic mode (as for example a character breaking the fourth wall and addressing the audience directly), but rather what we thought was extra-diegetical slowly integrating itself into the diegesis, along a kind of dream logic.

It would be interesting to see if such a maneouver could be done in comics…

Mike–I agree about the pages of empty panels. I thought that was quite successful, the most successful part of the book in the more traditional, “illustrative” mode.

As for the shapes in the background being akin to Plato’s Forms–I kind of don’t see it. To begin with, there are the bafflers, not just the snail, but many others–and the female figure in star-spangled hotpants doesn’t look to me like it’s intentionally made to look “victimized.” More than that, though, if Miller had tried to illustrate Plato’s Allegory, he would have seriously bungled it–after all, in Plato you can only see the real forms by going outside the cave! (And, I should add, Miller has been forever drawing his characters in silhouette, it’s kind of his signature–just look at the DKR cover.)

“I can’t recall the exact instances, but some comics or movies have featured sequences where the creators switch back and forth from, say, the hero fighting the villain, and a hawk battling a snake. That’s an effect, in a less obvious fashion, that I think Miller is employing here.”

Well, that is done in “Lone wolf and Cub” (one of Miller’s main influences), and actually he did it himself in “Martha Washington.” But there the symbolism is made very clear. I just don’t see it in the same way here…

One of Andrei’s posts on the logic of illustration is here.

I’m appreciating Noah’s point about how all comics artists are outsider artists– except nobody could convincingly call Dan Clowes or Art Spiegelman outsider artists. “Outsider” sometimes just seems to mean “fascinating working-class specimen.”

But it can really just be almost anyone who comes up with something novel; fine artists of note were not infrequently weirdos aesthetically, unless they’re actively borrowing from other artists. Which makes it even better that Miller is appropriating Piranesi and McCay and Eisner and everything. His desire to not appear as an outsider artist makes him even more of an outsider artist.

Anyhow, I stopped reading Frank Miller in the ’90s, but those images are aweskumm!!

Noah–I can totally see the Fletcher Hanks comparison (and it may be that I appreciate HT in the same way). But I think the point is too broad, to see the entire comics industry as “outsider art.” Switching to a parallel art, there has been a ton of “genre hackwork” in the movies, but only a few creators tend to be seen as “outsider,” for example Ed Wood. I’ve seen people describe Kirby’s late work as “outsider art,” which is baffling to me–we’re talking about a man who a) basically created the medium (comic-books) in which he is working, b) whose compositions contain narrative sophistication along the lines of the greatest narrative Baroque artists (for example), and c) whose late rendering technique and design can be fully explained in theoretical terms coming from modern art criticism (I’ve often showed the parallels between, say, Kirby and Franz Kline). In such a case, to cast him as “outsider,” in a way, is to find an easy way out of coming to terms with the obsessive imagery of his late period which, if accepted as created by an actual “insider,” so to speak, demands a much deeper critical engagement.

Well, that kind of argument about Kirby is what I’m saying when I say that comics might be a way to put pressure on the idea of outsider art as a useful category. It’s not so much that I’d like comics to be seen as outsider art as that thinking about comics as outsider art makes the category of outsider art difficult to hang on to…which I think is probably a good thing, because I don’t like the category very much.

Does that make sense?

Pingback: Carnival of souls: special extra-large edition « Attentiondeficitdisorderly by Sean T. Collins

Sorry to disagree, Andrei, I otherwise like the general idea of going beyond the knee-jerk, and weighing both sides.

Miller has done one good book. Just one. Ronin.

After that, it’s all been downhill. Ok, so Ronin was pretty far up, so the way down isn’t immediately crap.

But all that you see as good in this book of his seems to me to be reflections of those earlier things. He’s swiping from himself.

The masturbatory nature of this book, and of his body of work in general, is tiring.

Maybe he should take up oil painting? A little terpentine won’t do his brain any harm.

—————————-

Andrei Molotiu says:

…As for the shapes in the background being akin to Plato’s Forms–I kind of don’t see it. To begin with, there are the bafflers, not just the snail, but many others–and the female figure in star-spangled hotpants doesn’t look to me like it’s intentionally made to look “victimized.” More than that, though, if Miller had tried to illustrate Plato’s Allegory, he would have seriously bungled it…

—————————–

That “female figure in star-spangled hotpants” looks either dead or unconscious; she’s slumped over, being held up by one of the Bald Goon Creatures; while to her right, another woman, unresisting, is being clutched/groped by a BGC…

And no, I don’t think this was a careful, intentional, accurate illustration of Plato’s Forms. I wrote, “Are these something like Plato’s Forms?”

Nonetheless, these Not-There figures — aside from that pesky snail (and whatever other exceptions there might be; I’ve only skimmed through the book) — bear some kind of a relationship, on a primal, emotional level, to the characters and action going on in the foreground. There aren’t toasters and CD players and eggs floating around in the background; we see tyrannosaurs, fanged fish, helmeted warriors and hairless Untermenschen…

—————————–

Just as the night rises against the day, the light and dark are in eternal conflict. So too, is the subhuman the greatest enemy of the dominant species on earth, mankind…

Although it has features similar to a human, the subhuman is lower on the spiritual and psychological scale than any animal. Inside of this creature lies wild and unrestrained passions: an incessant need to destroy, filled with the most primitive desires, chaos and coldhearted villainy.

A subhuman and nothing more!

——————————

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Untermensch

——————————

Noah Berlatsky says:

..It’s not so much that I’d like comics to be seen as outsider art as that thinking about comics as outsider art makes the category of outsider art difficult to hang on to…which I think is probably a good thing, because I don’t like the category very much.

——————————-

Well, the term is nowadays being (at least on occasion) supplanted by “self-taught art.” ( “The Foundation for Self-Taught Artists presents and promotes information and scholarly research on self-taught, outsider, vernacular, and visionary artists…’ http://foundationstart.org/ ).

Unless we’re dealing with some oddball minis, a comics creator working in the industry would hardly have the chance to go off on the wild tangents, ignore what’s trendy and popular in the field. Even mainstream creators with a pronounced oddity to their work — Fletcher Hanks, Basil Wolverton — did work that fit the parameters of genre.

The Undergrounds at least had room for “outsider” sensibilities such as Rory Hayes…

Some stuff: http://www.escapeintolife.com/showcase/outsider-art-web/

“Norman Pettingill: Backwoods Humorist”: http://www.amazon.com/Norman-Pettingill-Backwoods-Gary-Groth/dp/1606993194/ref=sr_1_4?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1328620254&sr=1-4

Andreas–“Ronin” is great (as a matter of fact, I’m teaching it beginning on Thursday in my Graphic Novel class), but the middle of his run on Daredevil (roughly, “The Elektra Saga,” or the issues he both wrote and drew himself), “The Dark Knight Returns,” and, with collaborators, “Born Again” and “Elektra Assassin” are just as good–and, actually, I think they’re better if you read them all and can have them resonate with each other.

I don’t quite see how what he’s doing here is “self-swiping”–I was trying to argue that the bizarre aspect of HT is actually going against the grain of what made Miller’s work in the ’80s great. I don’t remember huge out-of-place snails and dinosaur heads sticking out of walls in Daredevil, or in Ronin for that matter. When there is imagery in the background in Ronin, say, it’s there intentionally, to add to our overall understanding of the world depicted–something which, pace Mike, Miller doesn’t do in HT.

Andrei, what a coincidence!

Self-swiping; well, he’s always had the little details, maybe not as blatantly absurd, but it’s been there. Like in Big Guy and Rusty, there’s stuff in the background.

Here it seems like there’s more non sequitur stuff, but also like he’s making less of an effort: I mean, ok, it is entirely possible that he’s taking more artistic license, letting himself be free of limitations more.

It could also just be that he’s adding these elements in a calculated manner, according to recipe (Like : Add 8% weird random crap, in a completely different style, to make this shit “deep” and shit).

Of course, it seems to me like the man’s sanity has taken a few critical hits, so who knows, maybe he’ll self-destruct in an explosion of pure art, and this is just the first tremors.

Self-destructing in an explosion of pure art doesn’t sound so bad–for the resulting art, at least.

To some extent, I feel that IS what he’s starting to do here. (Or, possibly, this already started to happen in DKSA.)

I’m preparing my lecture on “Ronin” for tomorrow–well, for later today–and just wanted to ask, has anyone else noticed the similarities between “Ronin” and “Don Quixote”?

For one (there are more), compare the ronin seeing the robots as demons to this well-known passage:

At this point they came in sight of thirty or forty windmills that there are on the plain, and as soon as Don Quixote saw them he said to his squire, “Fortune is arranging matters for us better than we could have shaped our desires ourselves, for look there, friend Sancho Panza, where thirty or more monstrous giants present themselves, all of whom I mean to engage in battle and slay, and with whos…e spoils we shall begin to make our fortunes; for this is righteous warfare, and it is God’s good service to sweep so evil a breed from off the face of the earth.“

“What giants?” said Sancho Panza.

“Those thou seest there,” answered his master, “with the long arms, and some have them nearly two leagues long.“

“Look, your worship,” said Sancho; “what we see there are not giants but windmills, and what seem to be their arms are the sails that turned by the wind make the millstone go.“

“It is easy to see,” replied Don Quixote, “that thou art not used to this business of adventures; those are giants; and if thou art afraid, away with thee out of this and betake thyself to prayer while I engage them in fierce and unequal combat.“

Miguel de Cervantes, Don Quixote de la Mancha, 1604, part 1, chapter VIII

Haahhaah! No. I hadn’t seen that…but yes, it fits entirely too well to be coincidental.

Cervantes and Koike/Kojima, upside down, backwards and seen via a broken mirror.

Oh well… this is all becoming similar to finding pleasure in a poem by Ezra Pound. The mind grasps for excuses… I guess that’s why so many artists find appreciation only posthumously; the audience, having had its fingers burnt so many times, plays the waiting game, not wanting to bet on a horse that might go mad in an unseemly way.

Well, there’s also the fact of Don Quixote reading old chivalry romances / Billy watching anime, etc. The parallels proliferate.

And there’s nothing wrong with “finding pleasure in a poem by Ezra Pound.” Yes, he later went nuts (probably literally, he did end up in an asylum!), but his stuff in the ‘teens and ‘early ‘twenties, especially, is some of the most radically innovative–and beautiful–poetry in English.

I know, I’m not trying to say I shouldn’t like Ronin, I am just saying that the mind has prudish tendencies (for lack of a better term). We want the artists to be Heroes, and the Heroes to be Pure, dammit! Why it’s so hard to enjoy something without hero-worshiping its creator is beyond me, but societally, I think that’s how it is. If we like something, we try to idealize the creator, and if idealizing the creator becomes impossible, we try to transfer that unto the creation. Ambiguity, bane of human complacency.

But in Miller’s case, I draw the line somewhere close to DKR, after that his mounting mental distortions become too apparent from his work, and I start to feel nausea reading it.

——————————

Andrei says:

…Yes, [Ezra Pound] later went nuts (probably literally, he did end up in an asylum!), but his stuff in the ‘teens and ‘early ‘twenties, especially, is some of the most radically innovative–and beautiful–poetry in English.

——————————-

Actually, Pound remained perfectly sane (even if anti-Semitic and pro-Fascist). His supposed madness — he was coached on how to “act mad” — was simply employed as a successful tactic by his admirers to keep him from being hanged for treason after WW II. (He’d done propaganda broadcasts for Mussolini, haranging “President Franklin D. Rosenfeld” and such…)

(Online details are scant — http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/crime/trial/other.html — but the article I’d read decades ago was convincing and comprehensive. [Looks some more; oh, yum! http://www.pbs.org/food/features/kitchen-careers-ezra-pound-cake/ )

Last night I’d read — in the February Harper’s Magazine — about the hubbub that resulted when the letters of Philip Larkin, a poet enormously popular in England, were published, revealing him to have all manner of racist, reactionary, misogynistic attitudes. The condemnation back then was well-nigh universal; it was written that even “defending him is despicable.”

Personally, I don’t give a shit. As long as they’re not running for public office or spreading their attitudes further than rants on blogs, what truly matters in a creative person to the vast majority of us, who only deal with their work rather than the person, is their art. Which often can be greater, wiser than the person themselves. (Or at least more fun to look at, anyway.)

As long as they’re not running for public office or spreading their attitudes further than rants on blogs, what truly matters in a creative person to the vast majority of us, who only deal with their work rather than the person, is their art. Which often can be greater, wiser than the person themselves. (Or at least more fun to look at, anyway.)

I understand this attitude, and I’d like to be able to embrace it wholeheartedly, but I understand too that for many people there are considerations that trump aesthetics. We may disagree, but it’s not philistine for people to reject on moral grounds that which they once might have found fascinating aesthetically.

“Also, as I’ve been thinking a lot about Kirby lately, ……. I don’t know if connecting the two in such a way is at all legitimate”

I think that point is entirely legitimate. Miller’s underground structure could be any number of Kirby’s bad guys hideout/lairs. The “Erich-von-Stroheim-in-The-Grand-Illusion half-face on the ground” could be the head to any number of villains in his 70s Captain America run. Most of the last several images in your article remind of Kirby. Balls-out cartooning but with dialogue even more imbecilic than his.

This is where I agree:This is a Hate book.Clearly he hates his art if he didnt he wouldnt make such a horrible one.I can see all the artistic and aesthetic references that have been implied-Money is such an inspiration for Frank.Dont know if he loves all bills or just the big ones.I would guess its just the big ones.Those are the ones that inspire.