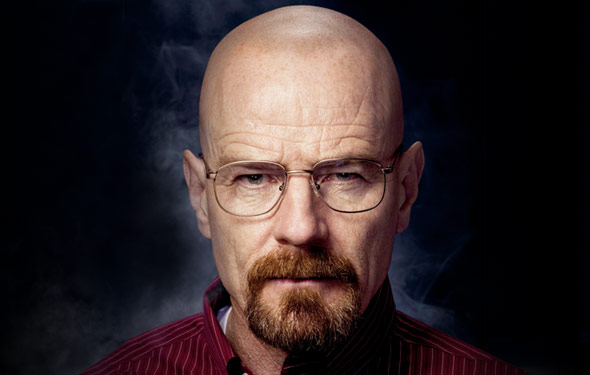

“Breaking Bad” is usually discussed in terms of its moral vision, and its unflinching depiction of Walter White’s decent into evil. Chuck Klosterman’s is probably the best-known encapsulation of the argument.

Breaking Bad is not a situation in which the characters’ morality is static or contradictory or colored by the time frame; instead, it suggests that morality is continually a personal choice. When the show began, that didn’t seem to be the case: It seemed like this was going to be the story of a man (Walter White, portrayed by Bryan Cranston) forced to become a criminal because he was dying of cancer. That’s the elevator pitch. But that’s completely unrelated to what the show has become. The central question on Breaking Bad is this: What makes a man “bad” — his actions, his motives, or his conscious decision to be a bad person? Judging from the trajectory of its first three seasons, Breaking Bad creator Vince Gilligan believes the answer is option No. 3. So what we see in Breaking Bad is a person who started as one type of human and decides to become something different. And because this is television — because we were introduced to this man in a way that made him impossible to dislike, and because we experience TV through whichever character we understand the most — the audience is placed in the curious position of continuing to root for an individual who’s no longer good.

Admittedly, I’m only through season 1 at the moment. But still, I see the trajectory Klosterman is talking about; Walt kills and sells meth and blows people up, and we still root for him.

Klosterman suggests that we root for evil because the show starts us off by sympathizing with Walt. I think that rather misses the point of the genre conventions though. You don’t root for a bad ass despite the fact that he’s a bad ass. You root for him because he’s a bad ass. Rorschach is cool not despite the fact that he shoots a policeman in the chest with a grappling gun, but because he does so. Similarly, when Walt shaves his head, goes into the drug dealers den, and uses his chemical no-how to create a huge explosion and intimidate the heavies — we don’t root for him despite that. We root for him because of it.

The first season of Breaking Bad isn’t coy about this dynamic. On the contrary, it presents good Walt, his good family, and his good milieu as hopelessly square, hypocritical, and ridiculous. Walt’s wife, Skyler, comes across as a moralistic busybody, snooping around after Walt and freaking out over his (supposed) pot use. Hank, Walt’s brother-in-law the DEA agent, is equally ridiculous, trying to scare Walt’s son straight in a painfully embarrassing scene in which he burbles anti-drug war bullshit while callously bullying the random druggies passing by. Walt himself is an ineffectual high-school teacher and a wimpish nonentity, sclubbing along in Hank’s shadow, boring his students, and generally epitomizing castrated middle-class suburban white lameness.

Until, that is, he embraces the dark side. After learning he has cancer and deciding to cook meth to support his family after he’s gone, Walt suddenly starts to become tough, sexy, powerful — a character who demands admiration rather than contempt. He defends his crippled son from bullies; he destroys the car of an insufferable cell-phone yakking stock trader; he faces down drug-dealers; he even starts subtly bullying Hank rather than the other way around. He changes from a colorless nothing to a dark hero — and who, given those options, wouldn’t root for the dark hero, not only because he’s a hero, but because he’s dark?

“Breaking Bad” does show the downsides of White’s choices as well. By stealing from the school science supplies for his meth cooking, he ends up drawing the police down on the saintly Hispanic janitor. The scriptwriters also take care to make a drug-dealer intelligent and thoughtful so we’ll sympathize with him when Walter has to kill him. Yet, the very effort to drive these moral lessons home can’t help but to contradictorily glamorize them. Walt is making Big Decisions with Big Consequences; he moves in a world of Drama and Tragedy. Who wouldn’t rather be Hamlet than Guildenstern?

As a contrast, consider Flannery O’Connor’s collection Everything That Rises Must Converge. All of these stories are about regular people — people like Walter — choosing between good and evil. But in O’Connor’s world, there’s nothing particularly exciting or sexy about going bad. Instead, sin is a small, stupid, sordid business, made up mostly of ingratitude, egotism, stupidity, and willful blindness. It’s not becoming the best damn meth-maker in the county — it’s sneering and taunting your mother as she has a stroke. It’s not killing a sympathetic drug dealer; it’s accidentally strangling your quite unsympathetic 10 year old granddaughter to death because she doesn’t behave enough like you. In O’Connor’s stories, sin makes you smaller than life, not bigger.

This isn’t to say that O’Connor’s stories are definitively better than “Breaking Bad.” Her range is limited — parent and child don’t get along; viciousness is exchanged; an epiphany is achieved just too late to forestall the tragic twist ending. The first time you read it, it can seem like a revelation. By the end of a book, though, it’s become wearisome; the boring scold repeating the same damn harangue for the sixth or seventh run through. At this point I’d probably rather watch another season of Breaking Bad than slog through another collection of the same damn stories by O’Connor.

Which is maybe the point. Evil in O’Connor is boring, which, by definition, prevents it from being interesting. In “Breaking Bad”, on the other hand, evil has the adrenaline rush of its genre conventions — it gives Walter purpose, direction, and emotional heft. “Breaking Bad” feels good, which probably tells you less about evil than it does about entertainment.

“Will” = “Walt”

Aw, crap. Fixed. I don’t know what I was thinking.

Yeah….ummmm….the main character’s name is Walt. It’s a little hard to take the rest of what you say seriously if you don’t even know the characters name.

Haha and as soon as I hit “add comment” you’ve gone in and fixed it. Much better.

These things happen when you don’t have a copy editor. As I mentioned on another thread, without such errors, there’s a slim possibility that somebody might start to think we were a professional outfit. Wouldn’t want that to happen.

I have a hard time with that Klosterman article, mainly because I don’t accept any of his premises or framings of the argument. His assertion that morality as personal choice is exclusive to contradictory, static, or contextual morality seems bizarre to me. This seems to suggest that it’s only because Breaking Bad allows Walt to be classified as “bad”* that his moral choices can be adequately explored. I get that flipping the character from one extreme pole to the other might make it easier to talk about moral choices, but…well, “easier” isn’t necessarily the most flattering descriptor for a piece of art, eh?

*I’d add that, at least so far (I’m only in the second season) Walt certainly doesn’t seem to be making a decision to be “bad,” he seems to be making decisions and rationalizing them based on what he thinks the greater good is. Which…is what every other character on every other show mentioned is doing, too, for the most part. So I don’t get Klosterman’s point at all.

Huh. I think, like I said, that there’s a certain amount of evidence that Walt finds badness exciting, though he certainly also rationalizes it….

I’ve been reading Foucault’s Discipline and Punish, which is very skeptical of law and of any kind of traditional morality; Foucault thinks those are basically just ways of enforcing power relationships. In that context, acts of illegality can be seen as either enforced by/ratifications of the law, or else as challenges to it, more or less politicized. I think Breaking Bad flirts with those ideas too; when Walt destroys the yuppie’s car, for example, that’s something like a blow against the class system, or an expression of class resentments.

It’s not very well thought through or articulated, though. For example, the real enemy, in some sense, is the health care system which forces Walt to a life of crime. But nobody ever rails against the health care system…though goodness knows, you’d think somebody would, since it’s destroying their lives.

I need to read Klosterman’s article more closely maybe…but I think the moral vision of Breaking Bad, such as it is, is fairly confused. Not that that makes it a terrible show or anything, but it seems much less thought through than the Wire. I don’t necessarily always agree with the Wire, but I feel like someone’s put some thought into what’s being said. Breaking Bad, at least through the first season, seems much more driven by the need to have shit happen and by more or less digested tropes (mad scientist; hate the suburbs; etc.)

Re: Klosterman quote, Breaking Bad’s treatment of morality is more complex than simply focusing on personal decision in doing evil. Yes, Walt is a free agent throughout the series, but the show develops the dynamic involved between his decisions and what the drug market asks of him. It’s not some ideal libertarian relation where Walt decides to sell drugs and others make their own rational decisions to buy or not buy his product. Accepting/rationalizing his initial decision to sell drugs as a good for his family (while only giving the users what they want), Walt is constantly faced with choices, not completely of his own making, where he has to increasingly compromise his morality to serve the “greater good” behind his original decision. Watching Walt’s befuddled attempts at rationalizing away these compromises is a huge part of the entertainment for me. The way this evolves into pure egotism is the arc of the show.

Re: rooting for immoral characters, I don’t buy that getting emotionally involved with a character necessarily entails a moral investment. I found Downfall incredibly tense, but at no time was I rooting for Hitler to escape that bunker. As in horror, you can be attracted and repulsed at the same time. This is a different kind of “coolness” or “rooting for” than is involved in a character that expresses your moral views. Specifically, the latter lacks the repulsion, you sympathize with the character’s motivations (a moral component). Entertainment like Breaking Bad creates empathy, but not really sympathy (well, in this case, your sympathy is dismantled as the show goes on).

I’ve been thinking about fictional accounts of evil since the earlier post on Buffy and Twilight. And I keep thinking back to that David Foster Wallace essay on Lynch in which, if I remember it correctly, he ascribes the creepiness of “Blue Velvet”to its implication that evil is always everywhere, just waiting for us to get swept up into it. He goes on to say that getting swept up can be liberating and exciting, but that it’s horrifying for anyone not participant (and even some of those who are). Lynch gets a lot out of letting the evil accrue over the course of the film and getting the audience in over its head.

I dunno’. I often think of evil as a sort of steady presence that cab overtake a person when circumstances line up in a particular way… Like a bacteria or virus that’s pretty much everywhere and that we all have but only makes us sick when our immune system is compromised.

Maybe we need to distinguish between evil and badness. Badness is is what many of the villains in pop fiction engage in. They don’t do evil so much as indulge in a set of unwelcome behaviors in order to achieve some end. Evil is done for its own sake.

But if you’re rooting for him because he’s a bad ass, then aren’t you invested in his bad-assness? I just don’t think it’s true that either the show or the viewer entirely rejects Walt’s evilness (for worse or, as Foucault might have it, better.)

Nate, I don’t really buy that. I think Terry Eagleton makes that argument in On Evil; i.e. that it’s only *really* evil if it’s done for its own sake. I think that’s a good bit too comforting. Shooting someone in the face is evil whether you do it because it feels good or because you are trying to save the world. Nobody just about sees themselves as evil. Either you need to get rid of the category all together, or it has to be about actions, not intentions.

Or maybe I should say not *just* intentions. Context matters, obviously, but having a rationale doesn’t make it right in itself.

Aren’t you rooting for the narrative to continue, more than for evil to succeed? The evil is enjoyable, fascinating, not something you agree with.

I tend to think of Lynch’s major theme as impotency (Mulholland Drive, Lost Highway, Blue Velvet, and even Wild at Heart). Evil tends to come out of people dealing with that impotency.

I don’t think it’s really possible to separate rooting for the narrative to continue from rooting for the evil to succeed, exactly. People and actions and morals are embedded in narrative. Those things aren’t just abstract structures. We think in stories (not solely, but an awful lot.) If evil is enjoyable and fascinating in a narrative context, then you are assenting to it, which is agreement of a kind.

Again, Flannery O’Connor doesn’t make evil enjoyable or fascinating, I don’t think. Evil’s sordid and depressing and you want it to end, mostly. There isn’t the genre rush there. I think that’s a pretty important difference (though it’s also interesting to note that O’Connor’s take on class relations are pretty ambivalent. People who want to change things or rebel are generally seen as despicable; there’s more incipient radicalism in Breaking Bad, I think, though it tends to get rerouted and funneled into a discourse of delinquency, as Foucault might say.)

Well, was Hannah Arendt consenting to totalitarianism just because she found it fascinating enough to write a book about it? Although I don’t know if she enjoyed thinking about it, surely there’s some form of enjoyment involved in reading her book.

The intellectual enjoyment of nonfiction and the visceral enjoyment of a plot-driven television show are not really equatable except in the most strained of mental exercises.

I think it’s simpler than this. The viewer/reader will root for the protagonist, regardless of that protagonist’s morality in almost all cases. Occasionally, a protagonist will just annoy the shit out of us (usually because the writing, or the acting, or whatever isn’t very good), and we won’t watch or read that text…but as long as a show/book/whatever is entertaining and we watch it, we’ll end up pulling for the main character. Why? They become like a friend of ours…someone we’ve known fairly well, for a fairly long period of time. We like our friends…even when they do stuff we don’t really like, because we know them well, can understand their motivations, etc. So…in some shows, people do root for or “like” the bland white suburban schoolteacher (Mr. Kotter…Martin Mull in that one sitcom…), and for other shows they root for or like the badass. Badassery can seem cool, but I don’t think that’s the determining factor here. Rorschach is the first character we meet…It’s clear he’s a protagonist of the piece. We learn about his life and his motivations, etc. When he shoots the policeman, we view him as a person and the policeman as a plot device…we don’t know him. It’s little wonder we root for Rorschach. If the policeman was the main character…and if Rorschach were a minor villain of the story, we’d feel bad for the policeman and mad at Rorschach…regardless of how badass his actions were. We root for James Bond…He’s an asshole. We don’t root for him because he’s an asshole…We root for him because he’s the center of our attention. The fact that he’s “cool” doesn’t hurt, but there are plenty of uncool protagonists who end up as the object of our narrative affections.

Yeah; Arendt wasn’t writing narrative, was she?

There are ways you can deal with evil in narrative without glamorizing evil. I think Flannery O’Connor does it; I think Tolkien does it, at least partly. You really do have to look at what the narrative is doing and how it functions, though. In Tolkien you’re rooting for a victory over evil; in Breaking Bad you kind of want Walt to keep doing worse and worse things as part of the narrative enjoyment. His badness is equated with sexual potency and with toughness and heroicness (at least through the first season.) That’s not the only way it’s inflected, but it is one of the important ones.

Again, this isn’t necessarily a knock on the show. You could see his actions as politicized rebellion against the stodgy middle-class conformity of American life — and I think the show actually sees it that way to some extent. Ideally, that tension would be ambiguity and add to the show’s interest. To me it mostly just comes across as confusion, though; I don’t think the show really knows what it’s doing the way the Wire does (or the way 24 does, for that matter…though 24 is crap.)

Maybe I’m repeating myself, but the point is that pleasure is a really important part of any aesthetic experience. I don’t think it’s adequate to just bracket it off from a work’s ethics the way you seem to want to do here. It inflects them and infects them (and vice versa.)

I haven’t read the Hannah Arendt…but it seems like dissecting and anatomizing evil is a pleasure of mastery and dominance, possibly? It doesn’t seem like that would contradict her ethical stance. The narrative pleasure of Breaking Bad isn’t about mastering evil, though, right? It’s about being mastered by it.

Eric, shouldn’t there be a consideration of what we choose to watch or read and why? If I ingest every entertainment equally, then your simplification holds. However, I’m much more likely to watch a James Bond film if I think the filmmakers intend to spotlight Bond’s horrible characteristics rather than downplay them.

I think you’re underestimating the extent to which people really do want to root for badassery. Just jumping back to The Wire for a second – Omar Little was never the main protagonist of The Wire, but he’s everybody’s favorite character because of how badass he is.

Eric, I think that’s simplistic. Our culture loves badass protagonists. Batman is more popular than Superman; Rorschach is more popular than Dr. Manhattan; Han Solo is more popular than Luke. Narrative positioning matters, but people aren’t just drones; they are actively invested in certain kinds of stories and in certain kinds of characters, and for particular reasons.

Walt is appealing both because he is the protagonist and because he is bad/cool. He’s also the protagonist *because* he is bad/cool, and the creators thought that would be a fun story to tell.

Noah,

I can see where making evil purely a question of intention is problematic, but I don’t think action is a particularly good measure of evil either. This is in part because actions are by and large intentional, so its unclear how we could ever separate the two. It’s also dicey because it presumes that there’s no difference between being evil and being mistaken.

Wallace was getting at the idea that evil is somehow beyond intention, it’s a social force that’s always there and that one can get swept into. Piggybacking on Charles’s comment this is what make evil so dangerous. It’s a category that’s available to us always, and becomes attractive at times when we feel powerless. Maybe it’s not that evil is something bad done for its own sake, but that evil is its own reward.

Noah

Just wait. They’re playing a long game. Think of it as MacBeth. You’re only responding to the first of five acts. It’s seducing you now but I’d argue by the end of season two it is impossible to fairly argue what you’re saying about the show is true.

Well, I’m not sure I’ll ever get there. I don’t like it that much, is the truth. But we’ll see.

Hey, no one needs to watch something they don’t like. Life is too short. Im just saying that your critique of the show is dealt with within the show itself. There’s hints of it already in the first season with the writers taking away Walt’s sympathetic reason for cooking when he rejects the offer to have his treatments paid for and lies about it. Things change very rapidly in season two. In partiular with the way the show uses sex. It’s like the writers strike gave them a chance to figure out what thy wanted to do. You’ve seen less than one sixth of the show. It might be a tad early for picking apart a pov on the series from further in.

I’ve seen a season of a continuing series. I think it’s fair to talk about it.

As I’ve mentioned in other contexts, if you only let people talk about a work of art who are willing to see and study every bit of it and all the additions, you end up having a discussion with nobody but fans (more or less.) The aspects of the show I don’t like are the things I’m discussing here. That’s the reason I might not go on with it. It’s certainly reasonable to say, well things change down the road. But if you move from that to saying that I shouldn’t have the right to talk about what I’ve seen…well, I don’t agree with you.

You’re also misreading my point if you think that taking away Walt’s sympathetic reason for cooking has much to do with what I’m talking about. I’m saying that the show finds his badness fascinating and attractive, and sells it as such. Taking away his sympathetic reason for cooking makes him more bad ass and evil and appealing, not less.

“Breaking Bad feels good, which probably tells you less about evil than it does about entertainment…The aspects of the show I don’t like are the things I’m discussing here. That’s the reason I might not go on with it.”

These sentences don’t exactly gel with your statements concerning the violence in Pulp Fiction (in your debate with Caro). Is it possible that you simply find Breaking Bad less entertaining? Is “identifying” with Walter any worse than “enjoying” the violence in any Tarantino movie?

Also, to go back to Charles’ points above, isn’t the big difference between Walter and Hitler/Eichmann the simple fact that one is fictional and the other(s) “real”? Hence our different attitudes towards them.

You’ve seen an aborted season of fewer than ten episodes of a show that makes clear changes in direction afterwards and then arguing that someone who is responding to the show at a later point in its development is incorrectlu assaying it. That’s all I’m saying. The show starts out providing us with reasons to synpathize with Walt, then takes those away while (I’ll grant you) reveling a bit in his badness but that is part of the trap that it’s building. It keeps either taking those sites of revelry away or problematizing them and calling into question who you are rooting for and why. It’s far more sophisticated than you are giving it credit for HOWEVER had I only seen the first handful of episodes your analysis would make a bit more sense. Which is why, rather than argue with you about how you’ve misjudged the show, I’d rather just encourage you to keep watching. I don’t even think you have to see the whole thing to see what I’m talking about. I’m trying not to get specific in deference to the spoiler police.

Apologies for any typos above. I’m writing this on a phone.

Isaac, you should be specific. I don’t care about spoilers; anyone reading this blog who cares about spoilers was probably driven away long ago.

Suat, I was thinking about Tarantino actually. Tarantino is a lot (a lot) smarter about the use of identification and violence and genre.

Just as one example, in Pulp Fiction, when we go from that scene in the car where they accidentally shoot the guy into ridiculous sit-com humiliation. He’s deliberately using sit-com tropes against the bad-to-the-bone image of the thugs. They’re still absolutely sympathetic…but they’re not sympathetic because they’re bad or tough. Instead they’re sympathetic because they’re ridiculous…which means that they’re badness ends up being kind of ridiculous and sad.

On the other hand, in Breaking Bad, the sit-com tropes are applied to Walt and his pitiful boring family; the drug world is set in opposition to that. The drug world is degraded and dangerous…but that makes it exciting, not ridiculous or sad. Tarantino uses genres to criticize each other and question the place of violence within genre; Breaking Bad (at least in the first season) mostly uses genre conventionally; that critique isn’t there.

The thing I don’t like about Breaking Bad is that it’s sentimental and conventional in ways I find really off-putting. The way we have to turn the drug dealer into a sympathetic character before Walt kills him so that we know it’s meaningful; the way the janitor is turned into a saint who happily mops up Walt’s vomit so we’ll know it’s a Bad Thing when he gets the shaft — it’s television paint by numbers storytelling, and it irritates me.

That’s why I’m not too confident that it’ll get better. There are serious problems with the writing and the conception. Maybe they’ll fix it, but that sort of thing tends to get worse as a series goes along, not better.

Well, that sort of makes sense. The comments had led me to believe that your problem with identifying with Walter was largely defined in “moralistic” terms. When in actual fact your problem seems to be that the “identification” is boring, conventional, and hence not entertaining. That would mean you find Klosterman’s critique true but somewhat bland and uninteresting when seen in the flesh.

In that sense, I think you’re right to drop Breaking Bad. There’s nothing meta about it which would remotely interest you. Despite all the hype, the series is pretty conventional in structure, dialogue, and plotting. There are exciting bits here and there but that has more to do with sequences of intense violence (or the threat of violence). If watching Walter’s rags to riches story or his MacGyverish moments don’t do it for you, then you need to give up on it.

On the other hand, there aren’t that many dramas out there centered on the recreational drug industry. I suppose there’s some commentary on capitalism in there as well (though it’s hardly profound). The acting is also pretty good at times. The reason for all the praise heaped on it is the same reason why your average superhero book gets high marks. The competition (and I watch a lot of the competition) is utterly degraded.

But would I trade Breaking Bad for something like Le Carre’s The Spy Who Came in from the Cold (equally commercial, breezy, and topical in its day; not a bit self-referential a la Tarantino)…not a chance.

Well…I’m saying that the conventional use of tropes and genre undercuts Klosterman’s point. So it’s not that Klosterman is right on content but the form is not very good, it’s that the form undercuts the content that Klosterman wants to be there.

I don’t much like the Spy Who Came in From the Cold either, honestly. I may prefer Breaking Bad.

Actually, I don’t remember much about the sympathetic drug dealer or janitor you mention above. So it’s hard for me to comment on how “sentimental and conventional” those scenes were. I don’t see too much of that in the later seasons it has to be said so maybe you’ll get more out of them? It ups the ante on the genre elements so that might appeal to you as well – “weird” characters, gangsters and stand-offs. There are some really slow bits with Jesse though. Those parts I didn’t care for.

Jason, I think we analyze the concept of evil in both fiction and the nonfiction work, but in a different way. The concept is still the concept, though. I find enjoyment in both that doesn’t really seem all that different to me. One realm might provide an example for the analysis of the other. The visceral aspect of the fictional narrative isn’t mutually exclusive with having an intellectual reaction to it. But what I was trying to say is that fascination (such as the joy of thinking about something) doesn’t entail moral sympathy with the subject of fascination. I believe that to be obviously true, which Arendt’s example demonstrates. I don’t see why the same isn’t true for fiction.

Eric, I mostly agree with you, but I didn’t particularly like Tony Soprano, yet I was really interested in following his story. I tend to prefer narratives featuring people I wouldn’t ever want to hang out with in real life. I’ll grant you that there’s the obnoxious asshole and then there’s Jar Jar Binks.

Noah, ‘glamorize’ is one of those rhetorical bogey-words. In order to tell Walt’s story about his descent into evil, the evil has to be attractive in some way. It’s a psychological portrayal (in part), so we’re supposed to understand what he’s feeling. I don’t think it’s the least bit difficult to separate my moral views from a story about bad people that I’m enjoying. I can feel pleasure while still thinking the characters are behaving immorally. Why is that some perplexing problem? Only a sociopath is going to think Breaking Bad is a story about a guy doing what he should do. When it comes to 9-11, I’m of the view that understanding isn’t the same as excusing. I enjoyed your line “Breaking Bad isn’t about mastering evil […]. It’s about being mastered by it.” But that’s not really applicable in the way you want it to be. It could be just as well applied to any work (Arendt included) about why people do evil things. The “mastering” is the understanding that hopefully comes from our experience of that work. (At least, I assume you didn’t mean Arendt was attempting to master evil to do her bidding.)

Suat, “isn’t the big difference between Walter and Hitler/Eichmann the simple fact that one is fictional and the other(s) ‘real’? Hence our different attitudes towards them.”

I think in terms of my being entertained by Walter and not Eichmann, this has everything to do with their relative status in reality. However, one should be worried about an individual who sees either as an example of good behavior. There are fictional stories that do basically argue for immorality being moral (Dirty Harry is my goto example), which makes the work itself immoral. (You can still be entertained without sympathizing with the immorality, though.) Breaking Bad definitely isn’t one of those stories.

Noah,

a vague SPOILER ALERT for those who haven’t seen anything past the 1st season!

.

.

.

Alright, examples of what Isaac is talking about come under Walt’s increasing tendency to see people as nothing but means to his goal. He at one point takes a strong moral stance against the use of children in the drug trade, but comes around to having to murder one. In the course of that transformation, he’s shown letting a girl die (the result of her own choices in life) when he could’ve saved her, because he knew she was going to be bad for his friend/business (the distinction is blurred, just like Walt’s original goal of providing for his family).

SPOILER END

On to Pulp Fiction:

“[Vincent and Jules a]re not sympathetic because they’re bad or tough. Instead they’re sympathetic because they’re ridiculous…which means that they’re badness ends up being kind of ridiculous and sad.

That’s kind of reducing audience attraction to these two characters just to that one scene. There’s also Jules’ speechifying and Vincent’s dancing ability and general way of moving, all of which is pretty badass, not ridiculous or sad. Walt doesn’t have any of that — he’s far more pathetic. As for attraction to a villain, there’s not a big gap between how Pulp Fiction depicts Marcellus (a very cool evil) and Breaking Bad depicts Gus, except the latter is more fleshed out.

Anyway, I really didn’t like the first season of Breaking Bad. In fact, I found it as generic as you (I preferred Weeds). I only picked it back up because so many friends kept pestering me to do so. It really does begin to pay off, particularly in the 3rd season.

Interesting that Isaac brings up Macbeth. Throughout Shakespeare, the evil characters are famously the most entertaining. Macbeth, Iago, Richard III,Edmund…in fact, the most beloved and popular of all his characters– Falstaff — is a pretty horrible person. There’s pandering involved, along with art of the highest order.

The screenwriter William Goldman said he understood why, in those first four films, the star playing Batman kept changing: ‘Batman’s a stiff’. The films (and arguably the comics and TV show) belong to the villains.

It’s hard to make goodness attractive in art.

Jules’ speechifying is most prominent when he rejects evil, though. And Vincent’s dancing is more than a little silly (though sweet) — and again works against his evilness, or at least isn’t about his evilness.

On the other hand, Walt’s attractiveness comes much more from being Dirty Harry; walking into the druggies den and blowing everybody up and getting out again. Jules and Vincent never display that level of competence or cool. They’re always bumbling or thuggish when they’re commiting their crimes.

Walt’s a lot more like Dirty Harry.

You know, I”m not really talking about how the audience will react. The audience will react in lots of different ways. I’m talking about how the show seems to view the character (which is presumably what the moral vision is about, if there is one.) And the show seems to have a lot of contempt for Walt’s middle class milieu, and a good deal of enthusiasm/excitement about his turn to the bad. I don’t think it’s going to bring down our society around our ears or anything, but it’s mostly confused and stupid, and not especially sophisticated, either narratively or morally. It’s use of pleasure tends to work against the story it seems to want to tell, and which critics like Klosterman have claimed for it.

————————

Noah Berlatsky says:

…Shooting someone in the face is evil whether you do it because it feels good or because you are trying to save the world…

————————–

Now, now; would shooting Hitler in the face be evil?

As for enjoying the adventures of a less-than-admirable protagonist, one can…

– Vicariously appreciate their doing actions we know that, however satisfying they might be (kicking an overbearing boss in the nuts, f’r instance) would land us in a heap of trouble in the real world

– Admire toughness and derring-do; whether it’s for a good or evil cause being irrelevant

– Cheer (as old movie audiences did) as Little Caesar or Cagney in The Public Enemy do all matter of socially-disruptive behavior ( http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k4R5wZs8cxI ), then cheer again as they get their violent comeuppance, order is restored (and the audience is reassured they did the smart thing by not robbing banks and such)

– Get in touch with our “dark side” by relating to the characters in the safe context of a fictional work, video game…

Noah,

“Walt’s a lot more like Dirty Harry.”

Really? Harry versus Walt versus Jules and Vincent. But the major difference between Breaking Bad and Dirty Harry is the latter defends the hero’s actions as being good and the former clearly doesn’t. (I don’t much see Pulp Fiction as a moral exercise, so you’re on your own there.)

As you’ll see, there are some murders in Breaking Bad that involve the devil you know killing the devil you don’t know as well, which do have something of a celebratory aspect, but there are other murders that are depicted as utterly heinous.

“Jules’ speechifying is most prominent when he rejects evil, though.”

Only if you ignore the first major speech. I’d say he’s equally badass in both instances.

“[Breaking Bad] seems to have a lot of contempt for Walt’s middle class milieu, and a good deal of enthusiasm/excitement about his turn to the bad.”

I don’t get that at all. If the show has contempt for anything, it’s what one has to do to achieve power. I don’t see the show as about class, though. It’s more a violent satire of the libertarian ideal of a self-made man.

“I don’t get that at all”

Yeah. Klosterman doesn’t either. It’s plain as day to me though.

Breaking Bad is ambivalent about Walt’s actions, at least in the first season. When he takes on his son’s bullies or beards the drug lord in his den or destroys the yuppie’s car, he’s supposed to be both bad ass and at least to some extent in the right. Again, that’s inflected by the extent to which the middle-class morality of his family and friends is shown to be hypocritical and ridiculous.

The show would be a lot better if it was able to think about class or systems, the way the Wire is. It may be satirizing the libertarian ideal, but it also buys into it. For example, as I said, there’s no critique of the health care system; in fact, the show goes out of its way (and well on into improbability) to make sure that you don’t blame the health care system. Which strikes me as pretty stupid, because our health care system really sucks. It seems like you should be able to get that message across without condoning murder. But Breaking Bad isn’t much for subtlety or thoughtfulness, at least from what I’ve seen.

Jules’ second speech rather undercuts the first. He explicitly mocks it.

Tarantino’s a very moral filmmaker, I think. It’s a lot of what he’s about, and a good bit of the pleasure I take in his films.

“Jules’ second speech rather undercuts the first. He explicitly mocks it.”

I agree. He has a change of heart. But he’s still just as badass in the first instance.

Imagine if you stopped at the first speech and what your impression of PF’s portrait of Jules would be. Now apply that to BB.

“Imagine if you stopped at the first speech and what your impression of PF’s portrait of Jules would be. Now apply that to BB.”

But Pulp Fiction is a singular artistic unit, whereas a serial television show is a larger whole made up of individual singular artistic units. By its very design, Breaking Bad has to be ingested and reacted to in pieces. The person sitting down to watch the pilot as it airs has no guarantee that (a) the show will continue as long as its creators want or that (b) the creators even have a plan. Nor is that necessary to critique the pilot, or the first season, as standalone units. This isn’t like critiquing a movie based on the first ten minutes, or critiquing a graphic novel based on one out-of-context page. Noah is addressing what should be fairly complete pieces of a larger puzzle. A TV show may be novelistic, but it ain’t a novel. Different rules apply.

1. That idea of TV pretty much made shit of most dramas in the past shit. It was a definite step forward when the possibility of a sustained narrative was allowed.

2. Breaking Bad is most definitely a sustained narrative. Its intent is tell the character arc of Walt, to show how he turns into a bad guy.

3. Pulp Fiction is actually a set of short stories that share characters.

4. The disadvantage of serialized TV for a single narrative is that once a chapter has been filmed, you’re stuck with it. That doesn’t mean that the later chapters are any less important in interpreting what the story is trying to say than in a film or novel, though.

5. Finally, I don’t take issue with someone only talking about a part of a story. It’s just that anyone who’s seen the last 2 seasons of BB knows that it takes a far more negative view of killing than either Pulp Fiction or Dirty Harry. (Not that I have a problem with Pulp Fiction’s less moralistic take on its characters’ actions. That’s not the point of the film, any more than the point of BB is to critique our health care system.)

i guess i really wanted to get the idea of shit across in point 1.

Breaking Bad is quite anti-killing in the first season. Part of the issue is that the way it’s anti-killing is sentimental and manipulative; I don’t really believe it. To be fair, the badassness of Walt is also pretty cliched and rote.

I think people are hearing me as saying that the problem is that the show is immoral. As I tried to say to Suat, that’s not necessarily the issue. The issue is that it’s been praised for its thoughtful take on morality; for having a unique and profound moral vision. Whereas, to me, mostly its moral vision seems confused and mired in genre conventions that it doesn’t question or even really seem aware of.

Charles,

1. I don’t think the notion of episodes operating as discrete artistic units disallows continuing narrative. Twin Peaks, Deadwood, The Wire, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Friday Night Lights, Sandbaggers, Downton Abbey…I mean, those are just off the top of my head and based on my tastes, but those shows were pretty successful at expressing plot and theme on both the micro and the macro. I’m not saying that every single episode has to start from scratch, just that the form is what the form is, and pretending it’s something else because you’d rather be making a five-year mini-series doesn’t do anyone much good, because regardless of intention your product is going to be ingested as discrete units in an open-ended chain.

2. I guess I should also say that I think that Breaking Bad (at least what I’ve seen) does function in the way I describe above. The story of Walt “going bad” is told in each episode. Critiquing how that story is told in each episode, and certainly over the course of a first season, is not less valid than critiquing the show as a whole – just because later episodes might contradict earlier ones doesn’t necessarily change the earlier episodes.

3. Pulp Fiction is NOT a set of short stories. Pulp Fiction is a single movie made as a pastiche of a collection of short stories. There’s a huge difference. Pulp Fiction is designed and presented as a single artistic experience, not as a collection of units.

4. As per #2, it doesn’t mean that later episodes have to inform critiques of earlier episodes, either.

5. My argument is largely theoretical/formal and I have no opinion on the actual view of killing on display in any of these three works. Or at least none well-formed enough to be pertinent in this discussion.

Any chapter in Pulp Fiction is far more independent than any later episode of Deadwood. It is closer to The Wire, though, where each chapter is more meaningful if you’ve watched the rest, but still fairly complete on its own. I’d say the Laura Palmer story is closer to Deadwood than Pulp Fiction or The Wire.

From what I can remember of BB’s first season, Noah is accurate enough. I’m saying that you’re supposed to feel a certain way in that season that is subsequently going to be dismantled. So his drawing any conclusions about what the show is trying to say about evil or badassery is necessarily limited, and is, in fact, wrong once you get more into the narrative. That doesn’t make the first season good (it isn’t), but it does mean that the show gets better and does interesting things with what was set up during the first season. Overall, the show is overrated, but it does get pretty good, comparable to The Wire or The Sopranos, but no Deadwood or Twin Peaks or Lost.

It isn’t about how independently you could view a piece were you to separate it – it’s about the form it’s created in and for.

In any given episode of Deadwood, I can correctly surmise the themes of that episode, and the themes of later episodes don’t “correct” the themes of earlier episodes. In your formulation, later episodes of Breaking Bad “correct” the themes of the early episodes. I wouldn’t dispute that formulation, except to point out that, as far as I’m concerned, that means those early episodes do actually express that theme regardless of the influence of later episodes, because they exist and were imparted as discrete artistic units. I’m pretty sure at this point you’d disagree with that assertion, but I wanted to make sure it was clearly stated.

Of course, I think we’ve also got some aesthetic differences, as I wouldn’t rank The Wire or The Sopranos on the same level (the latter is far more wildly uneven) and I think Lost is just abominable past the nonsensically amusing first season (which is another point where Klosterman and I depart as well, come to think of it.)

“It isn’t about how independently you could view a piece were you to separate it – it’s about the form it’s created in and for.”

And I don’t see BB as being written to stop at the first season.

But we’ll just have to agree to disagree.

Well, my point has never been that it was “written to stop” but rather that, by necessity of the form it is created in, each episode and each season exist as independent entities, intention of the creators having nothing to do with it whatsoever. But I assume we agree to disagree on that as well

Dude, you should keep watching the show, I had my doubts after the first season as well, but those cliched sentimentalities that you talk about are part of the larger picture and set the stage for the more horrific acts that Walt (and just about all the other main characters) take part in later down the road. Plus, you haven’t seen any Saul Goodman episodes yet!!

Pingback: Really, It’s OK to Ignore Game of Thrones and Mad Men | CCLAH

Hard to comprehend why anyone would assume that by watching the show, we viewers were all rooting for the villain.

The moral core of Breaking Bad is a Nietzschean one. You realize this when you can see that there is a “shadow Walt” that is in the background throughout the narrative, but only pops his head up once in awhile. More specifically, Walt is an echo of his former partner, Elliott Schwartz. We’ll remember from the Gray Matter episodes that his wife, Gretchen, and Walt were once involved. But things went bad for Walt in that relationship and so he had to pack up and move out to Suburbia while the Schwartz’s became increasingly successful. Walt’s continuing relationship to his life since then is characterized by profound resentment; he has switched out a beautiful and brilliant w/life for a plain middle class one. He is stuck in a job that he’s impossibly overqualified for. Cancer makes Walt realize how powerless he’s felt and, seeing how successful the Schwartz’s company has become, he sets out to take power however he can get it. Ever since his encounter with the Schwartz’s he’s no longer Walt; in that same episode (Gray Matter) he turns into “Heisenberg”. Only his interaction with the Schwartz’s could remind him how much his life had degraded. He wasn’t strong enough to conquer Gretchen (it’s strongly hinted in Peekaboo that he left her because he was intimidated by her class on a vacation with her family), and being reminded of his impotence, along with the unhealthiness of his body, makes him into a powerful monster. His actions are hard to rationalize in later seasons if we don’t keep this in mind.

Breaking Bad is thus about the women in Walt’s life, and how they have destroyed him. Vince Gilligan is apparently surprised by the fact that the people revile Skyler, but the reason that they revile Skyler is because she represents the degradation of a “great man.” No matter how much they humanize her or make her into a “rich” moral character, she will still play the same role of settling for white bread because he was unequal to the best. Gretchen is the impossible goal of effortless power, and Skyler is the constant active reminder of the social obligations that tie Walt to mediocrity.

So basically it’s a superhero power fantasy driven by misogyny and white male resentment.

That dovetails with my reading, I think.

Ah, but Noah, you’ve gotta know that Sr. Reece has a point. The show vacillates between allowing Walt to be hyper-competent at times (Super-Villain Walt) and at other times just lucky (Bumbling Walt). This is because it needs to show simultaneously that Walt is a man of incredible resource, but also that he’s “not really cut out for this sort of thing”. Remember, Walt is fundamentally impotent; even in his strong moments he is not Superman (who is notoriously dull for only being hyper-competent) or Dirty Harry. So he’s strong(er than Skyler), but not strong enough (for Gretchen), and where he’s not strong enough, things bumble along helpfully with a wink.

Superman isn’t hyper-competent all the time; sometimes he’s Clark Kent.

The doubling trope, sometimes the uber-Father sometimes the puling wannabe-Father, is totally in line with superhero narratives.

Walt’s in over his head (with women) like Tony Montana, not rising meteorically (over women) like Michael Corleone (at least, Michael Corleone in Godfather I exclusively).

I think Owen’s point is that, unlike your average Spider-men and Supermen, Walt’s bumbling self is not restricted to his off-hours — to his family life, work life, non-villainous life. Cranston often plays Walt as bumbling at the very same time that he is authentically being (or trying to be) “super.” So you will see him sneaking around, Bond-like, even as a branch whacks him in the face or his 50-year-old body can barely clamber over a short wall. (Such moments are rarely played for laughs, though.)

That just means it’s Spider-Man rather than Superman, right? Or the Hulk; any Marvel title really. My paradigm is not rocked.

The Castrated Avenger. The self-pitying white male trope of modernity.

Fits with Ender’s Game nicely, actually. Super-smart nerd placed under stress; responds with more or less justified uber-violence.

Geeks love genocide.

I’m conflicted, I really love the show, I do like seeing Walter play out his monstrous male power fantasy even as it’s completely unjustifiable and harms everyone around him. He is the protagonist, the viewer delights in his competence but I don’t think the narrative justifies his actions in the same as in Ender’s Game for instance. Walt’s fans hang onto him doing all this for the family which is clearly wrong, he’s just selfishly living out his dream.

I guess it does makes sense in a sort of monstrous übermench morality that neither the show nor Walt’s apologists cop to.

The show is very well made and acted but it’s not a great favorite of mine.

I think it’s perfectly acceptable for a viewer to buy into/enjoy Walt’s “monstrous male power fantasy.” In practical terms, very few people are going to watch a commercial TV program for 5 years where the main character is a *completely* repulsive/incompetent piece of shit. More importantly, viewers are clearly meant to identify with some aspects of Walt. He’s the embodiment of white middle-class male empowerment fantasies but this narrative is constantly thwarted by the destruction Walt leaves in his wake. Viewers are essentially being asked to “break bad” with Walt, and their (variable) need to see him win is a feature of this process. Any lack of compassion fans have for his wife or victims can be similarly attributed. You hardly see anyone writing about Walt’s drug addict victims for example. This callous forgetfulness makes Walt’s brand of evil understandable.

Walt basically loses everything except a sliver of his pride and the sense of a job well done. So Noah is right in identifying the superhero characteristics of Breaking Bad – it’s basically Beowulf as a monster. It’s not completely clear at the end that he finds his actions regrettable (just a few of the consequences).