Boots in Time

The first major touchstone in Fredric Jameson’s epic 1991 Postmodernism, or The Cultural Logic of Late Capital Capitalism is Van Gogh’s A Pair of Boots.

Jameson refers to this as “one of the canonical works of high modernism,” and goes on to argue:

that if this copiously reproduced image is not to sink to the level of sheer decoration, it requires us to reconstruct some initial situation out of which the finished work emerges. Unless that situation–which has vanished into the past–is somehow mentally restored, the painting will remain an inert object, a reified end product impossible to grasp as a symbolic act in its own right, as praxis and as production.

This last term suggests that one way of reconstructing the initial situation to which the work is somehow a response is by stressing the raw materials, the initial content, which it confronts and reworks, transforms, and appropriates. In Van Gogh that content, those initial raw materials, are, I will suggest, to be grasped simply as the whole object world of agricultural misery, of stark rural poverty, and the whole rudimentary human world of backbreaking peasant toil, a world reduced to its most brutal and menaced, primitive and marginalized state.

Fruit trees in this world are ancient and exhausted sticks coming out of poor soil; the people of the village are worn down to their skulls, caricatures of some ultimate grotesque typology of basic human feature types. How is it, then, that in Van Gogh such things as apple trees explode into a hallucinatory surface of color, while his village stereotypes are suddenly and garishly overlaid with hues of red and green? I will briefly suggest, in this first interpretative option, that the willed and violent transformation of a drab peasant object world into the most glorious materialization of pure color in oil paint is to be seen as a Utopian gesture, an act of compensation which ends up producing a whole new Utopian realm of the senses, or at least of that supreme sense-sight, the visual, the eye-which it now reconstitutes for us as a semiautonomous space in its own right, a part of some new division of labor in the body of capital, some new fragmentation of the emergent sensorium which replicates the specializations and divisions of capitalist life at the same time that it seeks in precisely such fragmentation a desperate Utopian compensation for them.

There is, to be sure, a second reading of Van Gogh which can hardly be ignored when we gaze at this particular painting, and that is Heidegger’s central analysis in Der Ursprung des Kunstwerkes, which is organized around the idea that the work of art emerges within the gap between Earth and World, or what I would prefer to translate as the meaningless materiality of the body and nature and the meaning endowment of history and of the social. We will return to that particular gap or rift later on; suffice it here to recall some of the famous phrases that model the process whereby these henceforth illustrious peasant shoes slowly re-create about themselves the whole missing object world which was once their lived context. “In them;” says Heidegger, “there vibrates the silent call of the earth, its quiet gift of ripening corn and its enigmatic self-refusal in the fallow desolation of the wintry field.” “This equipment,” he goes on, “belongs to the earth, and it is protected in the world of the peasant woman. . . . Van Gogh’s painting is the disclosure of what the equipment, the pair of peasant shoes, is in truth. . . . This entity emerges into the unconcealment of its being;’ by way of the mediation of the work of art, which draws the whole absent world and earth into revelation around itself, along with the heavy tread of the peasant woman, the loneliness of the field path, the hut in the clearing, the worn and broken instruments of labor in the furrows and at the hearth Heidegger’s account needs to be completed by insistence on the renewed materiality of the work, on the transformation of one form of materiality–the earth itself and its paths and physical objects–into that other materiality of oil paint affirmed and foregrounded in its own right and for its own visual pleasures, but nonetheless it has a satisfying plausibility. At any rate, both readings may be described as hermeneutical, in the sense in which the work in its inert, objectal form is taken as a clue or symptom for some vaster reality which replaces it as its ultimate truth.

For Jameson, if the painting is not to be decoration, if it is to have meaning, then it needs to include meaning — which is to say, narrative, or history. The decoration, the burst of color, is merely a surface to be consumed unless it has a context attached to it. That context is both the past (the long path of the immiserated peasant through his life of toil, up to his door, and to the moment when he removes these, his boots); the present (especially in Jameson’s second reading, where the painting creates the peasant woman and the field and the earth around itself) and the future (as the burst of Utopian color, the yearning towards a decidedly material relief.) The painting calls for a story to complete it.

This is obviously a very Marxist reading. But it’s also a comics reading.

At first calling it a comics reading may seem a little startling, because there is often a very strong push in comics crit against ideological readings. Recently on this site, for example, Matthias Wivel argued:

Which brings me to the other issue I have with the critical reception of Habibi, and comics in general: the lack of sensitivity to how the visuals are integrally determinant of the work. Critics tend not to look beyond the surface qualities of the drawing in comics, and then proceed to discuss whatever conceptual issues are at stake without devoting much attention to how those issues are manifested visually. Even a cursory examination of the reviews published so far of Habibi should demonstrate this. Only a few have been entirely positive and several have been strongly negative in the conceptual assessment of the book and its ‘writing,’ but the majority of the reviewers have nevertheless taken time to commend the ‘art.’

Matthias argues that critics “tend not to look beyond the surface qualities of the drawing in comics” — which can not entirely finesse Jameson’s point that drawings are, literally, surface. Matthias goes on to a lengthy and thoughtful discussion of, among other things, Thompson’s line. But the discussion of that line itself seems flattened by Matthias’ circumspect refusal to give it a context. He criticizes Thompson for failing to convey complexity of emotion — but why exactly are we supposed to desire complexity of emotion? He points out the lack of spontaneity in Thompson’s line — but why does it matter if the line is spontaneous or not? Without the ideology that Matthias denigrates, the critique is left foundering in a thin (because untheorized or acknowledged) humanism or else, as Jameson suggests, in the even thinner realm of decoration, where the ink is appreciated in its inkness, a connosieur’s pleasure. (One could, of course, defend connosieurs and decoration — but I don’t know how you could go about doing that without wading into the deeper shoals of ideology.)

To be fair, Matthias isn’t calling for non-ideological readings; just ideological readings which pay more attention to surfaces. But (as is the way with such things) he ends up so chary of ideology that he seems to be paying attention just to the surface — looking so closely at the trees that the forest drops out of the peripheral vision. Jameson insists on looking beyond the image, on saying where it is coming from and where it is going to. For Van Gogh’s shoes to have meaning, they have to be in the world, affected by it and affecting it; they have to be made for walking. Matthias, in contrast, seems at times to want the line to draw a circle around itself, keeping the world, with its messy moral judgments and harumphing ideology at bay.

What’s strange about this tack is that it seems to miss the essence of comicness — to call for a focus on surface when sequential art has that “sequence” right there in its name. The comic book does exactly what Jameson does; it provides the situation for each image, and for each image the situation.

Comics in Jameson’s terms then seem to be what others have sometimes praised them for being; that is, resolutely committed to old-fashioned artistic values — a medium committed to Van Gogh rather than to Jameson’s post-modern exemplar, Andy Warhol:

Now we need to look at some shoes of a different kind, and it is pleasant to be able to draw for such an image on the recent work of the central figure in contemporary visual art. Andy Warhol’s Diamond Dust Shoes evidently no longer speaks to us with any of the immediacy of Var Gogh’s footgear; indeed, I am tempted to say that it does not really speak to us at all. Nothing in this painting organizes even a minimal place for the viewer, who confronts it at the turning of a museum corridor or gallery with all the contingency of some inexplicable natural object. Or the level of the content, we have to do with what are now far more clearly fetishes, in both the Freudian and the Marxian senses…. Here, however, we have a random collection of dead objects hanging together on the canvas like so many turnips, as shorn of their earlier life world as the pile of shoes left over from Auschwitz or the remainders and tokens of some incomprehensible and tragic fire in a packed dance hall. There is therefore in Warhol no way to complete the hermeneutic gesture and restore to these oddments that whole larger lived context of the dance hall or the ball, the world of jetset fashion or glamour magazines.

Yet this is even more paradoxical in the light of biographical information: Warhol began is artistic career as a commercial illustrator for shoe fashions and a designer of display windows in which various pumps and slippers figured prominently. Indeed, one is tempted to raise here–far too prematurely–one of the central issues about postmodernism itself and its possible political dimensions: Andy Warhol’s work in fact turns centrally around commodification, and the great billboard images of the Coca-Cola bottle or the Campbell’s soup can, which explicitly foreground the commodity fetishism of a transition to late capital, ought to be powerful and critical political statements. If they are not that, then one would surely want to know why, and one would want to begin to wonder a little more seriously about the possibilities of political or critical art in the postmodern period of late capital.

But there are some other significant differences between the high-modernist and the postmodernist moment, between the shoes of Van Gogh and the shoes of Andy Warhol, on which we must now very briefly dwell. The first and most evident is the emergence of a new kind of flatness or depthlessness, a new kind of superficiality in the most literal sense, perhaps the supreme formal feature of all the postmodernisms to which we will have occasion to return in a number of other contexts.

Van Gogh’s shoes look like they’ve just been tossed aside by a perambulating peasant; Warhol’s look like they’ve been purchased new from some shop window and then hammered flat. No one has worn them, no one will wear them; they are shoeness without story. If they have an ideology or a narrative, it is the narrative of no ideology and the ideology of no narrative.

In contrast, consider this sequence from Hideo Azuma’s Disappearance Diary:

The worker’s shoe here is not abandoned as in Van Gogh; instead, it is in its place, on the foot of an actual worker, inside a narrative. The upper right panel, showing Azuma tying his own shoe, wraps itself in time, the hands creating a whirlpool of motion with the shoe an anchor at the center. If the shoe in Warhol is dead and the shoe in Van Gogh points to life, then this shoe is actually alive, tied up with time. Azuma is effectively pulling on the working class identity, with its manual facility and expertise (“this made me look cool like a veteran.”) There is no burst of color, and no utopian vision, but the motion lines and, indeed, the panel progression still energizes the images. The narrative is in the picture and the picture in the narrative; the boot is not just its surface, but, as with Van Gogh, its story.

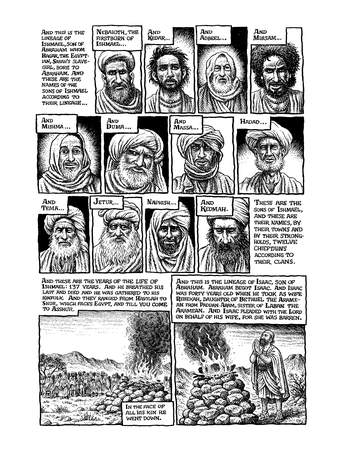

Comics then, can be seen less as an illustration of text than as a narrativizing of illustration — a form which pushes back against the shallowness of contemporary art practice by embracing the old-fashioned narrative and ideological virtues of prose. From this perspective, the achievement of R. Crumb’s Genesis is not giving flesh to every passage in the Bible, but rather giving narrative to every image. There are many, many Biblical paintings and drawings which show us Biblical characters as flesh and blood:

Crumb’s Genesis, however, is much more rare in insisting the the flesh of the Biblical image must be elaborated by the Biblical text itself. Crumb’s Bible is narrative; generations begatting through time, each with its own face that takes on weight only in relation to all the other faces.

In this sense, Crumb and comics themselves can perhaps be seen as analogous to doubting Thomas. Seeing is not enough; you also need the experience of narrative and the word. If post-modernism proffers the dehistoricized image, comics insists on reinscribing it. Backwards looking in every sense, comics does not exist without the preceding panel, the one that gives the present depth and meaning.

Boots in Space

In Postmodernism, Jameson specifically claims that the distinction between the modern and post-modern is in post-modernism’s spatialization of time.

A certain spatial turn has often seemed to offer one of the more productive ways of distinguishing post-modernism from modernism proper, whose experience of temporality — existential time along with deep memory — it is henceforth conventional to see as a dominant of the high modern.

Thus, Van Gogh’s shoes, imbued with a past and a future, become Warhol’s shows, shorn of history, existing as pure space. Or (though Jameson does not use this example specifically) the painful, crushing sense of a life passing in a stymied claustrophobia in Kafka’s parable of the man at the door of the law is replaced in Borges’ story “The Double” with a miraculous simultaneity, as an older Borges and a younger Borges suddenly exist in the same space, so that time becomes not an unavoidable weight but a sleight-of-hand juxtaposition. As Jameson says, “Different moments in historical or existential time are here simply filed in different places; the attempt to combine them even locally does not slide up and down a temporal scale…but jumps back and forth across a game board that we conceptualize in terms of distance.”

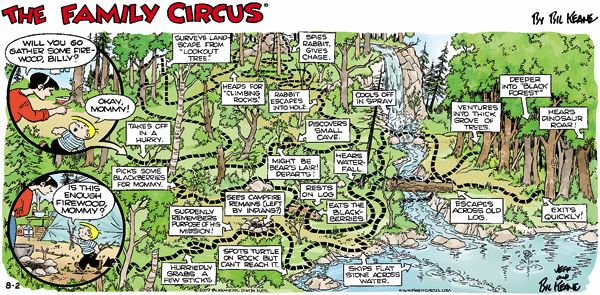

What would it look like if you turned time into space on a metaphorical gameboard? Maybe something like this?

The time of Billy’s journey is turned into a single schematic, a line which we can lightly trace. As Jameson says, different moments are simply filed in different places; the modernist pleasure of recuperation and depth is here replaced with the pleasures of surface and juxtaposition.

From this perspective, comics are not a backwards-looking modernist medium at all, but rather a post-modern engine for flattening time and narrative into space — of making time itself a manipulable, reified product. As an example, the Hideo Azuma boot-tying sequence:

Is the boot really energized and enriched by the narrative? Or does the existence of the narrative as spatial image allow time itself to become a mere decoration? The whipping hands and the boot so simplified it is almost a logo — Azuma presents this not so much as a specific boot in time, but as an iconic representation of a desirable skill, contained in a box and reproducible specifically for public consumption. Van Gogh’s boots were valuable for the life that had lived in them; Azuma’s are valuable because of their own image; they make him “look like a cool veteran.” Time — the working-class narrative of bootness — is flattened, mastered, and packaged for consumption. The boot points not to Marx’s utopian narrative, but to Lacan’s mirror stage; the exhilarating moment of mistaking a reflection for one’s past and one’s future.

You can similarly reinterpret Crumb’s Genesis.

Rather than using the narrative to give life to the image, the steady drumbeat of the images crushes the narrative. Generations are spread out across the page like moths pinned for display, or like collectable baseball cards. Narrative and ideology are systematized and controlled. The mystery of time becomes the fetish of space, patriarchs set together cheek by jowl with a repetitive obsessiveness reminiscent of Warhol himself.

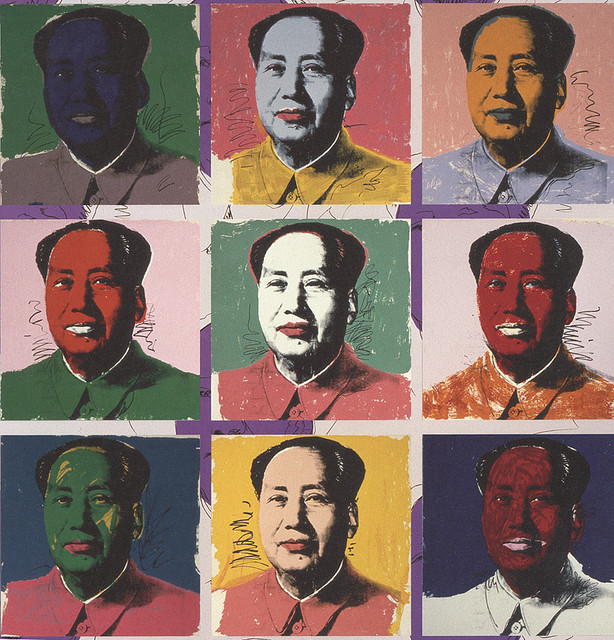

Warhol’s treatment of Mao is more explicitly parodic, but for that very reason it is almost more respectful. Mao and Mao’s image are, for Warhol, worth defacing and worth queering. Crumb’s Genesis, on the other hand, is treated as meaningless — one of the most consequent texts in history becomes a mere decoration, lines on paper. Ng Suat Tong’s is right that Crumb is “watering down” Genesis, but he’s wrong to think that this is a bug rather than a feature. If Crumb’s Genesis has a point, it is precisely the evacuation of content, the rendering of the Bible as merely another surface pleasure, its long history become a mere image no difference from any other that flickers across our optical nerves.

Jameson barely mentions comic book’s in Postmodernism; there’s one throw-away line in which he talks about post-modern bricolage as comic-book juxtaposition (and as schoolboy exercise.) In contrast, he devotes a great deal of time to video art, of which he says:

Now reference and reality disappear altogether and even meaning — the signified— is problematized. We are left with that pure and random play of signifiers that we call postmodernism, which no longer produces monumental works of the modernist type but ceaselessly reshuffles the fragments of preesistent texts, the building blocks of older cultural and social production, in some new and heightened bricolage: metabooks which cannibalize other books, metatexts which collate bits of other texts — such is the logic of postmodernism in general, which finds one of its strongest and most original, authentic forms in the new art of experimental video.

Nam June Paik, Electronic Superhighway

But if video art is the quintessential post-modern genre, perhaps it’s possible to see comic-books as its fuddy-duddy dialectical twin. Where video art fragments, comics reify. Where video art erases, comics embalm. Where video art heightens the ADD of advertisement, comics channels advertising’s depthless, deathless monomania.

Stan Lee/Jack Kirby “Save Me From the Weed!”

Stan Lee’s advertising huckster sloganeering (“A weed the likes of which the world has never known!”) is the perfect soundtrack for a medium in which time passing is shown by compulsive iconic repetition. Kirby’s helplessly neotonic weed, straining virilely against its roots, is a pre-Internet self-contained viral meme, its image replicating across the page like an embedded video or Warhol’s fecund Maos. Video art fractures identity into a unassimilable riot of images; comics turns repetitive image into identity. The evil weed next to the evil weed next to the evil weed might as well be a series of toys each in its box on the shelf in Wal-Mart, every iteration a pitch for all the others.

Comics’ crass refusal of the past as history, its suffocating nostalgia for and commodification of even the most dunder-headed images simply because they are images, can be a depressing spectacle. Yet, if comics epitomizes some of the worst excesses of the zeitgeist, is that not a sign of its relevance? As Jameson notes, there is no getting outside post-modernism; to the extent that we have a narrative, it is our narrative; to the extent we have a surface, it is our surface. We can mourn the rich texture and context of Van Gogh, but our mourning is itself post-modern, a loss based in our position after the modern has gone. If we pick up Van Gogh’s shoes again:

to illustrate a point or create a narrative, then those shoes become ours, not his. They lose their lodging in the past and find a space in the present, digitally replicated ad infinitum, almost like a comic book.

Transformation of time into space is standard and typical of modernism as well…

And much postmodernism is not about decontextualizing history, but about recontextualizing it—parodying and critiquing, not “pastiche” as Jameson says in the book.

For this reason, his effort to periodize into modernist/postmodernist is mostly nonsensical. “Pop Art” a la Warhol may be a kind of postmodernism, but it isn’t the only kind.

And the objection to “time as space” is an objection to virtually anything, as this is the standard (not particularly postmodern) way of attempting to understand such a difficult subject.

Bergson spent his whole career (starting in the late 19th century), trying to get us out of thinking of time as space.

I think dismissing Jameson’s book as nonsensical is maybe a little too easy? He’s a fairly smart thinker, and he’s trying to get at a cultural change which is important, I think. Making the postmodern move of saying, well, history doesn’t actually matter and nothing ever changes doesn’t so much refute his point as confirm it.

He talks a lot about a lot of different kinds of postmodernism, from Warhol (who is certainly an iconic example) to Doctorow to video art and on and on. I think the difference he points to between, say Faulkner (who is obsessed with memory and time as depth) and Borges (where time becomes a surface to explore and erase) is meaningful.

Of course, time as depth rather than surface is still a spatial metaphor. We could think about it that way instead if you’d like — that is, which spatial metaphors are more current, and how that works. I don’t think that’s anti-Jameson; he doesn’t really make a sharp break between modernism time, postmodernism space so much as he argues for a changed relationship between time and space.

I know your book is dedicated to recuperating history for the postmodern. As I said in my review, I tend to think you downplay the extent to which anti-narrative and non-narrative become flat tropes in postmodernism. I think that gets at Jameson’s argument about the difference between modernism and postmodernism; in the first, new narrative strategies can be seen as opening up a heretofore unexplored realm of understanding history; going forward means going back; the shoes have a past and a (because of the?) future. In pomo, though, the new is just endlessly repeated — Spiegelman saying “how can I write about the Holocaust?” isn’t a question about the unrepresentability of the past at this point so much as a rhetorical tic. And I think the comics form of Maus emphasizes that; Spiegelman rails against the marketing of his work, but the iconic cute mice repeated across every page compulsively reproduce their own commodification. Even the decrying of the Holocaust’s use as a marketing gimmick ends up as a marketing gimmick. Capitalism is representation and representation is capitalism.

The point being, I don’t think that Jameson is talking nonsense so much as that he’s got a different take on this stuff than you do — a take I find somewhat more congenial than yours (though I enjoyed your book a lot.)

But he’s basically wrong about Doctorow and he spews nonsense about the Bonaventure hotel, etc. Ragtime and The Book of Daniel are interrogations of an explorations of history…not an undifferentiated depthless surface of historical signifiers. His examples are either not particularly representative, or don’t say what he claims they do.

I like Jameson, btw, but I’m not being ahistorical when I say that the modernists were just as, if not more, preoccupied with or insistent on “time as space” as the postmodernists. That’s a fact.

He would do better to make some kind of distinction between a generalized “postmodernity” and “postmodernist” aesthetic objects or texts that often interrogate or critique “postmodernity” as he sees it. Doctorow’s Ragtime doesn’t have much in common with Star Wars (almost nothing, really), and saying that they are similar is distracting and misleading for anyone who knows both texts even a little. Likewise, the reading of the Bonaventure hotel seems brilliant until you realize that it’s not really difficult to navigate and Jameson must’ve just gotten lost there once.

I don’t disagree with some of his basic claims about “postmodernity”–but calling it “postmodernism” is as misleading as calling all things that take place in “modernisty” “modernism.” “Modernism” was often oppositional to many of the premises of modernity…the same is true of “postmodernism” and “postmodernity.”

In fact, postmodernity isn’t much different from modernity to my mind. We always want to jump to claims about shifts in historical moment, and to label them as something different (itself a condition of modernity and capitalism), but all of the “dramatic” changes of the internet, for instance, are extensions of the dramatic changes of the telegraph, telephone, high-speed print publishing, etc. The effects are, to my mind, just an increase, speeded-up version of the same. “Late capitalism’s” supposed move away from industrialism and toward information doesn’t really move much beyond industrial captialism, either…The factories are in different places, and the oppressed working class of industrial factories are globalized…but the essential structure is the same.

I like Jameson, actually, but I think “The Political Unconscious” is a much better book. Do aesthetic objects always reflect their political moment? Sure, to some degree…but paying attention to signal differences between those objects is also useful/important and Jameson tends to gloss over those differences in this book: Postmodernism.

Borges and Faulkner are more of the same time period than not, really. They differ widely, of course, but are they different because of modernism vs. postmodernism or just because they are different writers? I would say more of the latter.

There are plenty of “postmodern” books, films, etc. that are geared toward time, memory as depth, etc….and the reverse is also likely true. What about “6 Characters in Search of An Author”—A “modernist” period book, it has all of the hallmarks of postmodernism. Marquez’s 100 Years of Solitude is a later book (postmodern period), but is more like Faulkner than anything else (I know you don’t like Marquez, but it is all about history, politics, and memory as depth).

I’m not saying “nothing ever changes,” btw…but I would say that our preoccupation with obsessively looking for the “important change” is itself historical. In a culture, esp. in the U.S., which is always looking for the “next big thing”–the modernist/postmodern distinction is a version of that…as is the rush to get beyond postmodernism, to some kind of “post-postmodern world.”

I think the postmodern is still a useful category (though some, these days, reject that notion), but I don’t think Jameson’s delineation of it is supported by the evidence.

The essay is a fairly straightforward “base/superstructure” argument, but it’s too straightforward in insisting that all elements of the superstructure uncritically reflect the logic of the base. I think this is demonstrably not so. Linda Hutcheon’s now pretty old definition of postmodernism, for instance, insists that postmodernism is defined by its critical engagement with history. Her definition may be too specific itself, but it certainly suggests that Jameson’s claim that postmodernism is definitively ahistorical (paradoxically in its reflection of its historical moment) is problematic. Even the texts he himself chooses don’t really prove that, however…

My last sentence doesn’t make sense I now realize (cuz I added stuff in the middle). Feel free to ignore. (As if anyone is actually reading this).

I think you’re simplifying Jameson’s argument in a lot of ways. He’s perfectly aware, and talks about, oppositional tendencies within modernism and post-modernism. He talks a lot, too, about the modernist and postmodernist tendency to periodicize, and about the resistance among some to the idea that there is a difference between modernism and post-modernism.

Jameson also really is not saying that post-modernism is not historical. I don’t say that in the essay either (or at least, that’s not what I intend to say.) He’s saying that there’s a different relationship with history and a different relationship with space. (Jameson says pretty much exactly that…can’t find the quote now unfortunately….) I think in some ways that looks like a change from time to space…though actually thinking about it more, as I said in the preceding, I think it may make more sense to think of it as a shift from time as depth to time as surface.

And similarly, he doesn’t say Doctorow doesn’t care about history. He says that the treatment of history is…well, here:

That does seem very pomo to me, and different from many modernist works (though not perhaps from Orlando.)

I don’t know that I have a huge stake in always and everywhere separating the postmodern and the modern. I do think comics fits very interestingly into Jameson’s discussions of the post-modern.

Well…I haven’t read in a while…but I would say I remember being unimpressed by the gestures that you mention.

To me they read as simply gestures that don’t really account for the differences he claims to acknowledge.

Have you read his essay on Speed, though? It’s pretty brilliant.

No; I should read more of him, though. This book was really great (except for when he got into the weeds of Marxist academic theory. I can’t say I found that of much interest.)

They are definitely gestures in some sense…but as I said, his reading of Doctorow really doesn’t mean “this is not about history” as far as I can tell.

He definitely disagrees with you about the…revolutionary? liberatory? what would you say?…potential or acumen of postmodern thinking about history. He’s a lot more skeptical that one can escape the zeitgeist than I think you are, and I think also a good bit more skeptical about the achievement of postmodern literature (he’s more enthusiastic about visual art and architecture and genre work.) But I don’t think any of that makes him an idiot, necessarily.

I don’t think he’s an idiot. I’m sure the balance of opinion would be that I’m the idiot!

I would simply say that he doesn’t give due attention to the “oppositional” tendencies of much postmodern art/literature–at least not in that essay. The notion that there isn’t leftist/radical literature (and that such radicalism is reserved for himself) seems silly since much pomo art/lit is dedicated to exposing/interrogating the same things he himself is dedicated to exposing/interrogating.

Anyway, the Speed essay is called “The End of Temporality”— you may be able to get it here, though you may not: http://www.mediafire.com/?5egwt4ymihr

He definitely doesn’t say that there’s no leftist literature. He says that Doctorow is leftist literature, and I think he finds his exploration of the difficulties of the left profound and moving. And I think he’s pretty on top of the fact that he’s part of postmodernism too, and that postmodern art is looking at the same things he is. He really likes video art, for example; he really likes a lot of postmodern architecture. He uses it to think about time and space and the possibility of politics. Pointing out the ways in which it comments on those things isn’t dismissing it; quite the opposite.

Thanks for the link! I’ll check it out….

I think there’s certainly something to be said about the relative attitudes toward capitalism (and thus modernity) around the turn of the 20th century and the turn of the 21st.

I like The Political Unconscious too– trying to do a magical Hegelian thing with collectivizing our primal consciousness as ideology, which does, postmodernistically, flatten out quite a bit of human history– religion in particular.

I also just wanted to gratuitously reprint this thing I said to Noah in an email, re: this essay–

The fact that we’re all in this infantile semiotic desire/abjection swamp still means something. Nonsensical narratives are all the more awkwardly overdetermined for their meta-references, is the thing, practical narratives are magical, and miraculous narratives are possible– if only because they require no expertise, no proof, and no authority.

Also, while I continue demonstrating my talent of dumping icewater on even the most abstruse topics, let me mention the issue of satire– which I think is exactly the kind of feature of modernity– all early novels were satirical, it seems– that modernISM seemed to designate as inauthentic and decadent. Modernism was all about soul, and, while humor can have soul, it’s tough for satire. But probably that’s covered in Eric’s book.

Hey Bert. The point about satire is interesting…satire as the thing that skipped modernism? There’s lots of satire in pomo fiction…but maybe not so much soul? I guess Maus is supposed to have soul, though….

With your first comment…I think I’m not following you? It might help if you explained what you’re thinking of as each of the narratives. Are the nonsensical narratives pomo narratives? (Borges?) The practical narratives things like economics? Miraculous narratives I’m assuming are religious…but those usually seem to rely on authority of some sort…help?

Not that I want to detract from this elevated discussion but couldn’t you have chosen a better comic than “Disappearance Diary” as an example? That page sticks out like a sore thumb, like some deformed artistic runt.

Heh. I don’t actually think Disappearance Diary is worse than Genesis, necessarily. I don’t like either of them very much.

I didn’t know you hated that comic.

No, I’m just talking about the purely technical qualities of the art in question. I’m sure that was a subset of Matthias’ complaint. You have Van Gogh, Caravaggio, Warhol, Kirby, Crumb and then…Hideo Azuma?

Well, there’s the family circus up there too….

To be fair, Suat, boots were needed. Speaking of which, didn’t Derrida say of the Van Gogh that that’s not a pair of boots at all?

Did he mean in the Magrittean sense? “Ceci n’est pas une paire de bottes”?

I haven’t read the Derrida, though I think Jameson mentions him in passing….

It was partially that I needed boots.

I actually think that in terms of things to look at of all of these, my least favorite is the Crumb. There’s an energy to the advertising icon crassness of the Azuma that I can appreciate. I find the deliberate banality of the Crumb more oppressive.

There’s a discussion of Heidegger and Derrida on Van Gogh’s boots here. Looks to be a slightly different pair of boots, though…

Sorry to be absent… I mean practical narratives to be anything technical, from economics to science to HTML to advertising. Nonsensical narratives are high-art narrative (lit, comics, even video), and can also include advertising. Miraculous can be philosophy, religion, all things ideological– naturally, this can also include advertising.

I’m reading this Agamben book about the Trinitarian and divided nature of Western modern politics, which results in this idea of constant vicariousness– sort of like Derridean deferral/differance, but it refers in a circle insterad of off into some magical void. I think those three categories kind of work together in a similar way– technical narratives make use of nonsense, nonsense makes use of ideology, ideology makes use of technical.

And analytic philosophy manages to be all three: technical, magical nonsense.

I’d disagree that there’s no satire or humor in modernism. Ulysses, for example, is both funny and satirical. Virginia Woolf is also quite funny from time to time and, again, satirical (in Flush and Orlando…and the great short story “A Society”). Even To The Lighthouse has some funny bits about Mr. Ramsay. Kafka purportedly saw himself as a humorist with “The Metamorphosis” and other stuff too. I wouldn’t say that there’s no distinction between “dominant trends” in modernism and postmodernism, but blanket statements tend to fall down in the face of individual examples. I’m reading The Good Soldier Sveik by Hasek…a “modernist” WWI novel (at least it’s somewhat modernist), and it’s essentially one joke after another. The Death of Virgil is admittedly devoid of humor, though.

No, no, those are two left foot boots.

I unfortunately don’t have time to address this at length right now, but there are so many things that I think you get wrong in that essay, Noah :)

Firstly, I respect Jameson a lot, but his reading of Heidegger on Van Gogh strikes me as typical of the limitations of ideological “readings” — while compellingly formulated, I don’t think his Marxist interpretation of the beauty, the lift of transcendence in Vam Gogh, even begins to account for it. Heidegger’s does. His is a much more fundamental approach than Marxism — he is not interested in the shoes’ shoeness because they reflect the reality of the working man or the implied injustices of the social order, but rather that they reflect the very matter of *life. It’s almost metaphysical.

Which brings me to this oft-repeated notion that images are “literally” surface. OK, an image has a physical manifestation, yes, but how does this help us? It seems to me mostly the invention of literates who don’t trust their eyes. A line has as much life as a series of words, as much context if you will. I *don’t want Thompson’s line to “draw a circle around itself, keeping the world, with its messy moral judgments and harumphing ideology at bay”, I want to to engage, with Heidegger, its own very being, which is inherently of the world, better than it already does.

Ideology is all well and good, and we can’t exempt ourselves from it, and blah, blah, blah, but thinking too much according to the frameworks provided by the ideologies manifest in our culture risks blinding us to these qualities, about which ideology has very little to say.

And by the way, plenty of non-sequential art is narrative, carrying with it the past and the future. Comics. God love ’em, ain’t so special.

Aparently he wasn’t referring to this painting, sorry!…

James “Weird Al” Joyce, huh? Ulysses is an opaque, and humorous, crossword puzzle, which is not, in my view, comparable to satire– references are made for the sake of fundamental Irishness and novel-ness and erudite voguing prowess. Virginia Woolf– also funny, not afraid to reference history, also not satire. Pale Fire by Nabokov shades over from crossword puzzle into straightforward satire. Satire means that the primary project is to induce self-awareness and deflate tropes, not to create objects of pristine luminous depth.

Modernism cares more about reality, issues like whether boots “reflect the reality of the working man or the implied injustices of the social order” or “reflect the very matter of life.” Satire is dealing with constant upheaval, like capitalism.

Beckett and Charles Schulz are better than anything in theater or comic strips I’ve had the misfortune to experience– I’m not knocking modernist humor.

Thanks for responding Matthias!

Matthias, you say “a line has as much context,” but I don’t really see that in your reading. That is, when you talk about lines, you tend to talk about lines; it ends up being a connoiseurship argument and discussion, rather than a move to talk about metaphysics, or spirituality, or the conditions of life, or really anything other than the page. If surfaces and images refer in the way you claim they refer, then you should be able to talk about them referring.

I’d also just maybe point out that poking intellectuals for not understanding beauty, or insisting that we need to get outside ideology in order to understand art, are both extremely ideological positions, with a very old ideological pedigree.

I think one of the things the focus on surface can do with comics is, for example, to try to deal with the importance of the repetitive images, and the use of space as time, or of space to inflect time. The point isn’t that comics is the first or the only thing that’s ever done this (after all, the main example Jameson uses is a Van Gogh painting.) Rather the point is that comics does it especially notably and obsessively. So much so that if you look at a lot of comics, you can end up thinking of of any art which connects to sequence (like, for example, Van Gogh’s boots) as comics.

“Erudite Voguing Prowess” should be a band name.

I also had another good name idea, maybe for John Bellows’ band White Guilt: “Gentrify Me With Your Armpit Stench.”

“A Society” is definitely satirical. As are many parts of Orlando. The Ithaca section of Ulysses is also definitely satirical, as is the Nausicaa section (if I’m getting my sections straight). Some parts are serious and “luminous”–some parts really go straight for the yucks.

I always tell my students that Beckett and Schulz are fundamentally the same thing, though I often get funny looks for that claim.

Early Beckett (like Watt and Murphy) is quite satirical. Later stuff less so. But is Beckett a modernist or a postmodernist? Who knows. One of his big biographies is called “The Last Modernist” (a fairly dubious claim from multiple perspectives)…but, of course, he’s always a pillar of definitions of the postmodern too.

Noah, this is what Heidegger is talking about when he evokes the world in a pair of boots. You experience the whole of life be recognizing their materiality and what it suggests. The same goes for a line — it may suggest a mood, a temperament or a multitude of other things. Just because you can’t define it more precisely and elaborately the way you can with a piece of prose, doesn’t mean it doesn’t have meaning, or context. Everything does.

That being said, I don’t disagree with what you’re saying about comics. It just not particularly postmodern in itself.

As for ideology, I acknowledged what you were saying — with French theory context has become everything, an inescapable paradigm. I don’t deny that I speak from an ideological position, just that always thinking in terms of ideology tends to cut one off from certain aspects of life, because our dominant ideological frameworks, e.g. Marxism, emphasize certain things at the expense of others. It’s this kind of ideological discourse that I’m warning against — even if it definitely has its place and used — not *any vaguely defined set of assumptions each of us may bring to the table in any given situation (=ideology, more fundamentally defined).

Eric: I plowed through Ulysses in college (on my own, light summer fare), and my feeling was that the whole thing worked sort of like Moby Dick– it’s this big weird allegory about human nature, not a game of battling cliches.

Forget Pynchon, take a mediocre writer like Vonnegut– his novels intend to be funny, and they also clearly intend to borrow the epic pomposity of Hemingway and Joyce (and certainly not goof on them). Allegory and satire are not ultimately compatoble. Not that two people couldn’t sometimes read the same text and reach dofferent conclusions about the intention of the narrative, and I think some flickering back and forth within one narrative happens, but ultimately (I claim) you can’t be poignant and flip(/crass/grotesque) at the same time.

And you can do some sort of Hegelian thing and say that ultimately they’re somehow reconciled in their opposition, cause it is all post-Enlightenment First World people immortalizing their indigestion, but that also begs that there was a duality to begin with.

Matthias, it seems like you can go two ways here. Either the line is the material that evokes the world, and you need to look at it in dumb awe, in which case writing about it is pointless (as it seems like is telling other people that writing about it is pointless.) Or, alternately, lines, like boots, do in fact have contexts and ideologies, which are (it seems like) expressible, just as the contexts and ideologies of prose are expressible (though some would argue against that too, I suppose.) And if that’s the case, then you write about images much like you write about prose; by thinking about them and connecting them to other artwork and other bits of the world.

I don’t have anything against talking about lines. But I don’t see the contrast between talking about lines or talking about ideology. I can certainly see it as an opposition between connosieurship, or art for art’s sake on the one hand and Marxism/poststructuralism on the other hand…which I think is more or less what you’re doing.

My problem with that, at least subjectively, is that it just has very little to do with what excites me about art, or with how my aesthetic experience works. Yes, certainly, skill is something that can excite me; Hokusai’s lines are beautiful. But beautiful lines absent a context, or that don’t refer in interesting and lovely ways, aren’t lines that I want to stare at all that much. Hokusai’s lines do refer of course; he’s an incredibly witty, thoughtful, and profound creator. Crumb’s genesis is really the perfect contrary example; his virtuosity seems so intent on deadening his material that I just end up finding it ugly and stupid. Why it’s ugly and stupid is something that I’m interested in thinking through, maybe…but I sure don’t want to read it again.

I think there are various ways in which comics works interestingly with postmodernism. The way that images are so thoroughly imbued with narrative and so arguably with ideology is one. The obsessive repetition, and so, arguably, obsessive reification of images is another. The turning of time into flat space where, again, it can be reified, is a third.

Which brings me to this oft-repeated notion that images are “literally” surface. OK, an image has a physical manifestation, yes, but how does this help us? It seems to me mostly the invention of literates who don’t trust their eyes.

YES! Mitchell’s point in Iconology: that our own critical rhetorics are imbued with mistrust of images, with iconoclastic disdain for “surfaces,” with iconophobia: a very powerful prejudice, powerfully distilled in academia. The distrust of one’s own eyes is a strong motivator in much critical discourse, which continues to hover disapprovingly, but also fascinatedly, around the event horizon of those notoriously “seductive” superficialities: images.

Sontag claimed that true understanding requires narration, and that, I think, is what Jameson is trying to provide with his take on Van Gogh’s shoes. The results, though, are so doctrinaire, so predictably dogmatic. Note the iconoclastic disapproval marshaled by phrases like “an inert object, a reified end product impossible to grasp as a symbolic act in its own right”–Jameson’s whole critical procedure strikes me as tendentious.

Charles: “Jameson’s whole critical procedure strikes me as tendentious.”

As is everyone else’s.

Ha! Touché.

It’s a little tricky, though. Jameson loves the video art he discusses, and I think he liked the Warhol a lot too. Image as surface is an important thing to think about for him in part because it’s revealing; Warhol’s telling us something about how our world works. Jameson is definitely not coming from a place where modernism, good; postmodernism bad. They’re just (somewhat) different.

Similarly, I think acknowledging the surfaceness of comics, and being willing to think about the way images function as images, for good and ill, makes comics a lot more relevant to broader discussions of the arts and just generally of the world.

Like I said in the other thread, Puritanism isn’t such a bad thing in all instances. Puritans care about images more than anybody else, right? I don’t know that you’ve really gotten anywhere good if you’re so worried about iconoclasm that you back yourself into a meaningless and contentless aestheticism.

My sense was that Jameson was not a fan of Warhol, or Doctorow, or etc…though, again, it’s been awhile since I read it.

Well…but Ulysses is poignant, satirical, flip, crass, and gross…though maybe not all at the same time. The Penelope section is certainly crass (and sometimes gross, if memory serves) and poignant. Some sections work much more as satire than as an allegory of human nature—though, obviously, the whole certainly aims for the latter.

Jameson’s a huge fan of Doctorow, I’m pretty certain. He doesn’t really make any firm statements about Warhol, but my guess is that he likes him as well. He certainly likes the video art he discusses.

It’s really that the poignancy ruins the crassness. When Shakespeare’s characters are being crass, they’re not trying to simultaneously bludgeon you with profundity. Just with dense eloquence. There’s a big difference between being covered in shit and having it make you at one with the earth, and being covered in shit and having it not really change much of anything.

In my new triad of magical-technical-nonsensical (really just Imaginary-Symbolic-Real, to validate the Marxists=iconoclasts comment), the modern trend is to move things out of magic and into technique (business) and nonsense (pleasure), whereas the romantic and modernist thing is to try to put magic back into technique (Marx) and into nonsense (Wallace Stevens)– a form of highbrow fundamentalism, albeit a frequently sympathetic one, to be sure. But not built for pleasure. The weight of Joyce’s 10,000-word sentences is deliberately unbearable.

——————————–

Noah Berlatsky says:

…Yes, certainly, skill is something that can excite me; Hokusai’s lines are beautiful. But beautiful lines absent a context, or that don’t refer in interesting and lovely ways, aren’t lines that I want to stare at all that much. Hokusai’s lines do refer of course; he’s an incredibly witty, thoughtful, and profound creator. Crumb’s genesis is really the perfect contrary example; his virtuosity seems so intent on deadening his material that I just end up finding it ugly and stupid…

———————————

(???) “Deadening his material”? I’ve seen Crumb drawings of old buildings and kitchen appliances that pulse with life.

Not many of these handy online, though; one sample from his Vues de Sauve portfolio: http://stuartngbooks.com/images/detailed/19/crumb_vues_de_sauve_2.jpg

Typical Crumbiana here http://www.proof7.com/p7nyc/images/1980-crumb0128200-thumb.jpg , but in what way do the lines “deaden the material”?

My reading of Jameson on postmodern aesthetics was essentially that its a Marxist one. Marx, of course, was interested understanding capitalism…and Jameson’s reading of aesthetics is principally in seeing the “politics” or ideology beneath the surface.

Marx is also critical of capitalism, though…and insofar as Jameson sees these aesthetics as reflective of capital (which is a pretty big “insofar”–given that that’s the whole point), he is also critical of them. I remember puzzling over whether he “likes” some of these things (Warhol, Doctorow, etc.), and it’s pretty unclear, to my mind. In the end, though, I think not… Or, perhaps, initially he got some pleasure out of them…but on reflection they’re all just part of the “cultural logic of late capitalism”–and he’s not a fan of “late capitalism” or any other kind.

Though, again, it’s been awhile since I actually read it.

He has a passage where he explicitly says he really likes a lot of postmodern architecture and video art. As in, he basically says, “people ask me whether I like these things. And I do!”

It’s useful maybe to remember that Marx is pretty enthusiastic about capitalism in a lot of ways. He finds it exciting and seductive, but also as leading to the millenium.

There’s a follow up post about Wonder Woman here.

Mike, as I try to say in the piece, there’s a roteness to his treatment of Genesis which is both obsessive and, to me, oppressive. There’s always a component of that in Crumb, I think. Sean Michael Robinson talks about his reaction to it here. There’s a focus on the act of drawing as drawing that can seem (and does seem in the Genesis book) to be almost just about moving the pen rather than about anything that is represented in the content. It ends up being claustophobic, and not in a way I find aesthetically interesting or pleasing. I think, especially with something like Genesis, it comes across to me as a deliberate act of aggression and control. Lining up patriarchs like cans in a store display;it’s turning the Bible into a blank, banal list of products, advertising…well, Crumb mostly, I guess.

As Sean suggests in his essay, it’s possible to see this in an outsider art context; there’s a compulsiveness in Crumb that isn’t that far from someone like Henry Darger or Fletcher Hanks. Where their obsessions seem to feed their weird imaginative efforts, though, for Crumb in projects like Genesis the craft and the movement of the pen almost seem designed to erase or draw a circle around the imagination; to shut down context. (I don’t think that’s the case in all of his work, necessarily.)

Some readers have seen it as a Heideggerian move, maybe; to emphasize the beauty and power of the real, more or less in explicit contrast to the Bible’s magical narrative. I just don’t see that exactly, though. He’s not Van Gogh; there’s not really a romantic celebration of the real. It seems more like a retreat into the banal. He’s not putting magic into technique so much as he’s using technique to deny or circumscribe magic….

You gotta explain that some more, Noah — how does Crumb circumscribe magic? What does that even mean? To me there’s nothing overwrought about his drawing — it flows entirely naturally, a manifestation of somebody who really looks at the world, and at people. How is that so different from Hokusai? (I’m not saying he’s on that level, mind you, but the ambitions are similar, although Hokusai carries a certain kind of idealism in his abstraction, I think.).

As for connoisseurship versus Marxism/poststructuralism, it’s a false dichotomy. Connoisseurship is a lot more than appreciating art for art’s sake — it’s about believing in your subjectivity while building a very wide knowledge. No, it’s generally not theoretically reflexive, but it is deeply engaged with the world in which the art exists.

I want to stress once again that I’m not talking about technique, I’m talking about something altogether more mercurial and subjective — I’m talking about art.

If it’s a false dichotomy, you need to push against the dichotomy, not argue for the superiority of one side of it, Matthias. As it is, you’re not saying it’s a false dichotomy; you’re just saying connoisseurship is better.

And I’m talking about art as well. I just disagree that art is connoisseurship, or only connoisseurship. I don’t think that one gets closer to the world by being less theoretically reflexive, or that it means your especially deeply engaged with the world to be pointing to the movement of lines or insisting that you look only here and not there.

For Crumb; how do you see Genesis engaged with the world? What is especially engaged with the world about that image I’ve got up there? It’s just a bunch of small portraits stacked on top of each other like sardines. What’s engaged with the world about his bearded floating heads? They’re not individual or filled with life; they’re just a floating head because he needed a floating head.

Hokusai isn’t just a more interesting, more engaged artist because he’s got a craft advantage. He’s a more interesting, actually humanist artist because he actually looks at human beings, not just as sacks of flesh to stack one on top of the other, but as people who, you know, do things. I was just looking at the marvelous image from one hundred views of mt. fuji, I believe the second print, where there’s the mountain, and all those people bowing down to it, and then there’s that one guy pointing off at…something or other. It’s just really funny and witty — and it’s the second image. Crumb feels like he’s filling in a scantron; Hokusai wants to limn and celebrate the world.

We’ve talked about this before, and we just don’t see the same thing. I’ve already explained why I believe Crumb is deeply engaged with the world several times on this blog, perhaps most extensively in my piece on Genesis. Crumb doesn’t look at things? This just baffles me. Have you seen his sketchbooks?

Also, I don’t claim the superiority of any one approach. I’ve never said that there’s no value in ideological interpretation, just that there’s been a lot of the kind in comics where the theory comes before the work, which consequently looks like a nail to one’s ideological hammer.

This doesn’t mean that there’s no value in it. My own writing here should demonstrate that I don’t shy away from it on occasion, no? The only reason why I didn’t engage deeply, say, with the Orientalism in Habibi was that I wanted to make a different point. That piece was not conceived as an exhaustive examination of the work by any means — it was much more a critique of its reception, and the central point was that, wait for it, the ideological issues people were discussing in relation to the work *inhere not just in the “writing”, but in the images themselves.

So, we agree, right? (OK, not on Crumb).

For Crumb; how do you see Genesis engaged with the world? What is especially engaged with the world about that image I’ve got up there? It’s just a bunch of small portraits stacked on top of each other like sardines. What’s engaged with the world about his bearded floating heads? They’re not individual or filled with life…

I don’t know. This seems very puritanical, Noah (though I know you don’t always reject that label!). It seems very much like the kind of moralistic condemnation that came out of socialist realism, with its demands for obvious relevance. And it’s a cheap shot anyway, because Crumb’s Genesis is an entire work, one that must be seen across many pages and chapters, not just criticized on the basis of a page or cluster of images.

I think Crumb’s Genesis engages the world in precisely the ways you deny: by investing individual figures with individuality and physicality, by pointing out the breathing human passion behind the familiar tales, and by adding grace notes of observation and telling detail. I think I see what you’re not seeing, or not getting enough of.

Well, we agree about some things! I’m interested in thinking about the way ideology inheres in images, certainly; I think Jameson is trying to get at that, and my readings above are pretty closely focusing on the images rather than the narrative per se. But I guess I don’t exactly see you going from the line to the Orientalism in that piece? There are sort of gestures but the connections aren’t entirely made. Were you suggesting, for example, that the lack of spontaneity of the line was related to the use of stereotypical characters? That seems like an analog rather than a direct reading of the line as meaningful in itself though….

Thinking about the Hokusai…I hadn’t realized how good an example it is. The image literally points off the frame. The drawing isn’t just the drawing; it’s something more, something out there. That’s what makes it human and humorous. It’s not just in that one, either, though it’s very insistent there. Hokusai’s always breaking the frame in one way or the other, moving in and out of his box, spinning around and around the mountain. It’s a dialog between the world and the image, not an insistence that the world can be found through the image. I find it a much more exhilarating project.

Wish I could find that picture online…it’s such a great drawing…aha! Here it is!

Anyway…I don’t think I said Crumb doesn’t look at things. Sort of the opposite, really; in Genesis, it feels like all he does is look.

I don’t want relevance; he doesn’t need to be calling for a worker’s revolution. I just want some engagement with the world and with the text. A series of boxes with guys in turbans — the meaning I get out of that is that he’s deliberately wasting my time.

I’m totally happy to talk about the narrative and Crumb’s interaction with it, though I have trouble doing it without just making fun of him. But I do think Matthias is right that there’s a worth to looking at images as images not just as part of a narrative — or maybe that’s me who thinks that and not Matthias? Anyway, I don’t think one has to talk about the entire book every time one talks about the book. With the Azuma too, my comments about those images are I think generalizable to the entire narrative, even if I don’t explicitly do so (the manga is very focused on Azuma’s desire for authenticity through working-class cred; I talk about it at greater length here.

Anyway, I don’t think one has to talk about the entire book every time one talks about the book.

No, but when you reduce Crumb’s Genesis to “a series of boxes with guys in turbans,” as if one page could tell you the strengths and weaknesses of an entire book-length, you’re taking a cheap shot.

You and I disagree about this, as we’ve discussed before in the context of other book-length comics works.

No harm. No one can make you like Crumb’s Genesis, and that’s not the purpose of discussions like this anyway. I don’t happen to think Genesis is a perfect book, or even prime Crumb. But willful reduction, as in “boxes with guys in turbans,” is a rhetorical feint that gets pretty old pretty fast.

Er, that should be “an entire book-length TEXT”… Apologies.

It’s not a rhetorical feint. It’s talking about this particular page in front of us.

I’m happy to talk about other pages, or the work as a whole. I’ve done so before.

Not that you have to or anything, but rather than telling me what I shouldn’t be saying, why not defend the page if you think it needs defending? You could talk about it in the context of the rest of the work if you’d like. I think the way Crumb handles this sequence — rows of boxes filled with central casting faces — is pretty emblematic of the fill-in-the-box way he handles the rest of the book. Do you think it isn’t representative? Are you saying this page is particularly bad so it’s unfair to talk about it?

Not that you have to discuss it further if you don’t like, of course.

Maybe I’m not understanding, but it really seems like you are advocating a very different approach to criticism than Matthias. Matthias seems to be arguing for looking closely; for looking at the very line-work first, and only then (perhaps) moving out to a wider discussion. Whereas you seem to think it’s illegitimate to think about the page, much less the line, before talking about the work as a whole.

Noah… my takeaway from your exhausting Genesis roundtable was that the “magic” you want is basically shaped like a cross. In that spirit, it’s true that Crumb is hostile to things about Genesis: the sense in which it’s a priestly revision of tribal folklore. And, like the way an ancient Jewish priestly order used their literary means of production to claim a story or a rock for their ideology, Christians claim Genesis is talking about their guy- and would charge Crumb with the possessive, subtly hostile reading. Crumb the ex-Catholic’s version challenges those interests. How? With a close reading, but not neutral, that opposes his “volk” imagination of that tribal layer to the activities of an absurd icon of patriarchy.

When you say Crumb performed a “rote illustration,” your judgment is not based on a close reading of Crumb, or his source, which would demonstrate his careful reading, imagination, and subtle comedy. The enthusiasm in that roundtable for talking about other things he could have done is a critical tool which would disqualify any work of art that is not the universe. The roads not taken, limitations of method, and not-likeness to other versions define it- apophatically- as a work of art. Good? Bad? That’s where you read it.

The unstated position I see here is that Crumb MUST have worked like a mechanical drafting tool, must have as Ng politely suggests drawn with one hand down his pants and his mind on his thirty pieces of silver, because how else could he read Genesis so closely and not seen what you see in it? What other way could the result look like a compilation of lurid tribal gossip and power claims that you don’t want to read?

Crumb expressed a point of view about the Bible. Arguing with it requires acknowledging it exists. Arguing he failed to engage requires talking about what you think he failed to engage with. Right now your claims are up against the evidence of everyone’s eyes.

All right, Noah, now you HAVE to publish that article of mine on Hokusai.

——————————–

Noah Berlatsky says:

…there’s a roteness to [Crumb’s] treatment of Genesis which is both obsessive and, to me, oppressive. There’s always a component of that in Crumb, I think…There’s a focus on the act of drawing as drawing that can seem (and does seem in the Genesis book) to be almost just about moving the pen rather than about anything that is represented in the content. It ends up being claustophobic, and not in a way I find aesthetically interesting or pleasing. I think, especially with something like Genesis, it comes across to me as a deliberate act of aggression and control. Lining up patriarchs like cans in a store display; it’s turning the Bible into a blank, banal list of products, advertising…well, Crumb mostly, I guess.

———————————-

I can understand complaining about Crumb’s approach to Genesis as being “rote,” though seeing that he wanted the book to be a straightforward, faithful adaptation, it’s a matter of complaining about an artist achieving what he set out to do.

Having to cram a lot of material in there, working in a detailed rendering style, trying to keep it all looking visually consistent likewise works against “letting oneself go” as an artist.

As for his “Lining up patriarchs like cans in a store display; it’s turning the Bible into a blank, banal list of products,” many — along with myself — have praised how, where the Bible simply rattled out a list of names, Crumb richly individualized these guys.

Re his drawing being “a deliberate act of aggression and control”; haw! To that hideously oppressive “male gaze,” we can now add to the pantheon of vile baddies, and condemn the artist’s gaze! (Demographics being what they are, to be excoriated as male, “ableist,” colonialist, “cisgendered”…)

And attack (nothing aggressive nor controlling in doing that, of course; it’s only the “other side” that is so guilty) precision in rendering…the horror!

This is a case where an emphatic dislike of Crumb leads someone to attack every single thing about him, and his art; where every possible action is interpreted in a negative light. (If he expresses admiration for obscure blues musicians…racism is behind it!)

Reading on, I see…

————————————

For Crumb; how do you see Genesis engaged with the world? What is especially engaged with the world about that image I’ve got up there? It’s just a bunch of small portraits stacked on top of each other like sardines. What’s engaged with the world about his bearded floating heads? They’re not individual or filled with life; they’re just a floating head because he needed a floating head.

————————————

“Not individual”? The old TCJ message board discussion (with bigger, better scans) arguing the exact opposite is gone, but a glance at this shows the opposite: https://hoodedutilitarian.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/450.jpg . And they’re not Ditko-style “floating heads”; which doesn’t stop a triple repetition of the accusation. (Why let mere reality get in the way?)

And Crumb’s not “engaging with the world” here, he’s engaging with Genesis. Which is not exactly an airy, life-embracing work.

Hokusai is utterly wonderful; yet it’s amusing how an image you so highly praise — http://www.fulltable.com/vts/h/hk/im/02.jpg — great though it is, is as rhythmic and stylized as a Beardsley. While Crumb’s people are gritty, weighty, fleshly. We get loads of this “too, too solid flesh”; which is ironically why his attempts to render feminine pulchritude, as he himself bemoans, fall short: they’re too much solid meat (like those Pearlstein nudes, only with hatching) and less airy glamour…

In all fairness, contrasting with Crumb, there are artists such as Frank Stack and Eddie Campbell (the World’s Greatest Comics Artist, I firmly maintain) whose very “looseness” indeed has an airiness, “the breath of life” within it. By not so strongly emphasizing the solidity and physicality of what they draw, something else comes in…

The star of Stack’s delightful “Dorman’s Doggie”: http://deniskitchen.com/Merchant2/graphics/00000001/A_FS.PING.B.JPG

From the book in question: http://comixjoint.com/6_site_graphics/*Samples/2_Underground/dormansdoggie-art1.gif

A bit from Stack’s art for Pekar’s autobio “Our Cancer Year”: http://www.midmococo.com/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2010/07/ourcanceryear.jpg

Eddie Campbell, in dark and light: http://www.comicartfans.com/gallerypiece.asp?piece=619577&gsub=96092

http://images.tfaw.com/tfaw2007/blog/tfaw_playwright/tfaw_playwrightp5.jpg

http://tcj.com/journalista/eddiecampbellohmylord.gif

http://mindlessones.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/11/made-in-giner-635×480.jpg

http://farm3.static.flickr.com/2732/4093911042_aee2fc2a3b_o.jpg

Scott, actually I’d be quite happy with an impassioned atheist reading. The aggressive boredom I find…well boring.

What I think is interesting though, and what I brought up in this case, is the way that illustration can be used not to enflesh, but to deaden. I think there’s a tendency to say that if it’s being illustrated it’s making it more real — which is what Mike is saying. I think it can also be used to limit it, or to decontextualize it.

I sort of wonder…what would the reaction be if someone did to an illustration what Crumb did to the images? That is, what if someone just went through and provided largely neutral textual descriptions of a series of great masterpieces? The descriptions could be well written, even. I think you’d get lots of people arguing that the exercise was pointless, and that it detracted from and deadened the original work. I’m being accused of iconoclasm, but I think there’s a great deal of iconophilia in the way these issues are approached.

Also, just FYI, Suat’s first name is Suat; family name is Ng.

“Actually, I’d be quite happy with an impassioned atheist reading.”

Yeah, I see you saying that. But the issue is what you would be happy with an impassioned atheist reading of. Your disagreement is about the nature of the Book of Genesis. As you say, he could have adapted Christian theological readings of Genesis and argued with them as an atheist. But he didn’t. That wouldn’t make sense, because he wanted to deal with the Book of Genesis as an ancient text reflecting generations of tribal lore, and the strangeness of our society enshrining something that looks like the book he throws on the table.

Had Christian theology been Crumb’s interest, the question would be why restrict himself to Genesis as a battleground. And it’s true, Genesis is the object of contention. That’s where your perception of Crumb’s style as “hostile” and “dominating” comes from. His version IS restrictive, just like any performance of a play. (“I always imagined Hamlet being taller.”) The point is both whether he “gets” the material, which you need to argue forthrightly to argue at all, AND what kind of artistic statement he is making himself. As long as you’re not talking about the kind of reading you feel his visualization does not allow, your take is just baffling people for no reason and you’re not debating the issue. I see that in the roundtable and I see it happening here. And as far as evaluating his version, you’re treating every panel like a brick in an enemy fortress instead of reading the narrative.

Presumably if you would have liked a passionate atheist screed then you enjoy Sam Harris, Richard Dawkins, Christopher Hitchens, and so on. If so, you’re out of luck, he didn’t make the Understanding Comics of atheism. But if you’re ever interested in encountering an opposing view of the Book of Genesis, I recommend reading The Book of Genesis illustrated by R. Crumb.

I think Hitchens and Dawkins are kind of idiots, actually. But I like any number of atheist writers. Beckett’s cool.

Re: Genesis; it could have been a Jewish reading too. It could have been a passionate reading as an ancient text. It’s not any of those things. It’s just really literal representations, including cliched images of God, fat, hammy tears, pantomime idiocy, and rote layouts. Every so often he throws in some nonsense about matriarchal society bullshit, but he doesn’t have the interest or resources to make that a coherent reading. It’s not an especially fleshy version either, when you compare it to something like Caravaggio.

The one place where some passion comes through is in his depictions of sex and the female body, which are fairly familiar territory for Crumb by this point, but at least it’s something.

I don’t need him to do one reading or the other reading. I need him to do a reading; to interact with the text as if he’s given it some thought, rather than as if he set himself an assignment and is going through the motions.

To reiterate what I said in this piece; the defense appears to be in general that images are themselves a reading; that the act of visioning the scenes in the Bible makes them more actual and more real. I’m arguing that you could also see it as simply flattening it; refusing to think about the text except as visual surface. The violence is not in treating it as a fleshy reality (which he doesn’t, really) nor in treating it like an ancient text (which again; there’s not the sense of learning or of creating an actual past that that would indicate.) Rather, it’s in the indifference, the pomo reading of past and ideology solely as surface and (I think) as product.

It’s not that he’s restrictive, exactly. It’s that he’s *not* restrictive. It’s a bland refusal to engage with the text except on the most surface level. There’s a list of names; okay, here’s a list of faces. The text says someone listened; okay, here someone is cupping their ear.

Anyway…the roundtable really wasn’t all me. Lots of people defended the book. Peter Sattler’s argument is a really eloquent take on why the book often fails as visuals.

Anyway, Scott, you can take another swing if you’d like, and I’ll try to let that be the last word. Thanks for taking the time to comment; I appreciate it.

——————————–

Noah Berlatsky says:

What I think is interesting though, and what I brought up in this case, is the way that illustration can be used not to enflesh, but to deaden. I think there’s a tendency to say that if it’s being illustrated it’s making it more real — which is what Mike is saying. I think it can also be used to limit it, or to decontextualize it.

——————————–

“More real“? No, that’s not what I was saying. In the case of the depicted “lineage,” a batch of names were rendered as individuals, particularized. While it’s possible the names were actual, historically accurate — hence “real,” in the standard usage of the word — Crumb’s portraits were obviously not based on images of the actual guys.

Though I better understand what you’re getting at. As they used to say, watching a music video would replace what individuals thought of while listening to a song with the images in the video, Likewise, illustration of a text inescapably limits the contribution of the readers’ imagination; by making certain things concrete — say, choosing to depict an ambiguous scene one way — circumscribes authorial complexity.

———————————

…To reiterate what I said in this piece; the defense appears to be in general that images are themselves a reading; that the act of visioning the scenes in the Bible makes them more actual and more real.

———————————

Imagine reading a newspaper story of, say, a convenience-store robbery, then a Crumb comics version of the same event. Rather than “more real,” wouldn’t it be in-your-face obvious that we’re looking at a bunch of Crumb comic pages? Where the artist’s interpretation is another layer getting between us and the event?

Come to think of it, one of the unintended consequences of illustration is embodied in the reason why Ditko’s Objectivist comics stories have not been embraced by the movement. His graphically lively, yet hysterically shrill, stereotype-laden works only make blatant the simplistic idiocies of Objectivism itself.

——————————–

Noah Berlatsky says:

…[Illustration] can also be used to limit [what’s being illustrated], or to decontextualize it.

——————————–

How about limiting by contextualizing? Doesn’t Crumb’s visualization of events in Genesis — tribal clothing, details such as women’s nose-rings — make those people more alien, less relatable, to those who who are most “into” the Bible? (Not to mention, as with Ditko showing the idiocy of Objectivism, stuff such as the talking-snake bit making more evident how dim-witted a literal view of the Bible is?)

BTW, if anyone here’s having trouble posting comments in TCJ.com, I wrote up one re the Carl Barks article several (4? 5?) days ago, that the website “system” hasn’t let go through. “Not Found — Apologies, but the page you requested could not be found. Perhaps searching will help” was the message I’ve kept getting for two days when trying to post.

Timothy Hodler has informed me others have been having a similar problem, “the problem has expanded,” and the tech folks are working on it. This on Feb. 2.

Far as I can see (I’ve not checked comments to every article), there’s been no mention on the site of there being a problem, and after many attempts to post, it’s still going on…

Noah, there’s really no arguing with statements like that short of describing the book repeatedly. I nearly contributed to Peter Sattler’s thread but ran around the block instead. Since its reception is all positive, if it’s still open I’ll post a dissenting opinion.