[Images read from right to left. Wikipedia synopsis of Osamu Tezuka’s Princess Knight (1953) here. It’s a fairy tale romance for kids folks!]

* * *

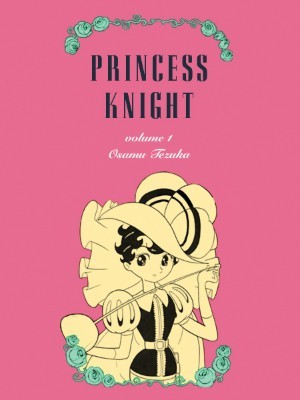

In the cloud strewn halls of heaven, the sexual fate of a group of cherubic “souls” are decided through a lottery of colored hearts. The consumption of a blue heart produces a boy child while the consumption of a red heart produces a girl. When the nascent Princess Sapphire is accidentally fed hearts of two different colors, her sexual fate is thrown into doubt (the covers to the Vertical edition of Princess Knight cleverly highlight this dichotomy). In order to rectify this disastrous turn of events, the supreme deity dictates that her blue heart must be extracted if she is in fact born a girl.

To be sure, this game of hearts has little to do with any real determinacy when it comes to sexual orientation or desire. Rather it is a foreboding of the future course of Sapphire’s life, a premonition of years of chaste crossdressing. The heavenly mix-up is not a recipe for hermaphroditism but for an individual fully at ease in the world of masculine (sword fighting, horse riding, wall climbing) and feminine (pretty dresses, fixations on princes, cat fights) activities.

When Sapphire is born a girl, she remains comfortable with and desirous of her femininity. It is her political circumstances which dictate her need to adopt masculine ways and this she does with a degree of reluctance but with utmost decorum. Her sexual orientation is never in question. As with much children’s literature, this is a world where secondary sexual characteristics like breasts are clearly on display but genitalia never spoken of. Sapphire’s enemies are unable to discover her true sex because she doesn’t have a vagina (nor do Tezuka’s men have penises for that matter) — this constraint undoubtedly due to the age of Tezuka’s readership but also accidentally suggesting that sexual divisions are a cultural product and not predicated on sex organs (hormones not withstanding).

Sapphire is forced to be a prince in public due to the careless birth announcement of a lisping doctor. The swift rectification of this mistake is impossible due to an arcane law which, like most fairy tale legislation, doesn’t hold up to much scrutiny.

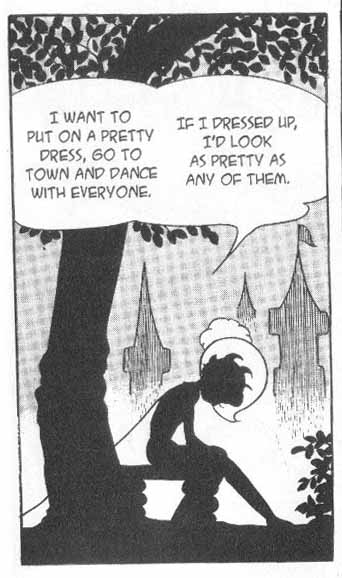

When we first see Sapphire as a young girl, we are swiftly apprised that she likes frilly things. Her transformation into a “prince” is a terrible inconvenience which she has come to accept over the years; an act of subterfuge which has caused such youthful bewilderment that she sometimes forgets to discard her heels in favor of more princely boots.

She is otherwise the consummate professional. Her mastery of disguise beggars that of Clark Kent and Diana Prince with their obfuscating spectacles and boring business suits. Her prince charming is blind to the wiles of his “flaxen” beauty the moment she discards her blonde wig and billowy ball gown. It’s either that or the magic of make-up, you never can tell.

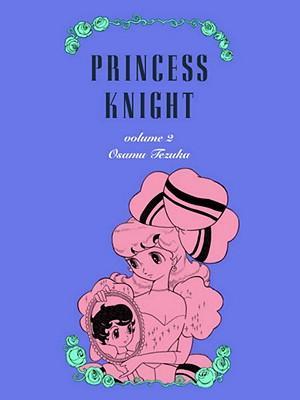

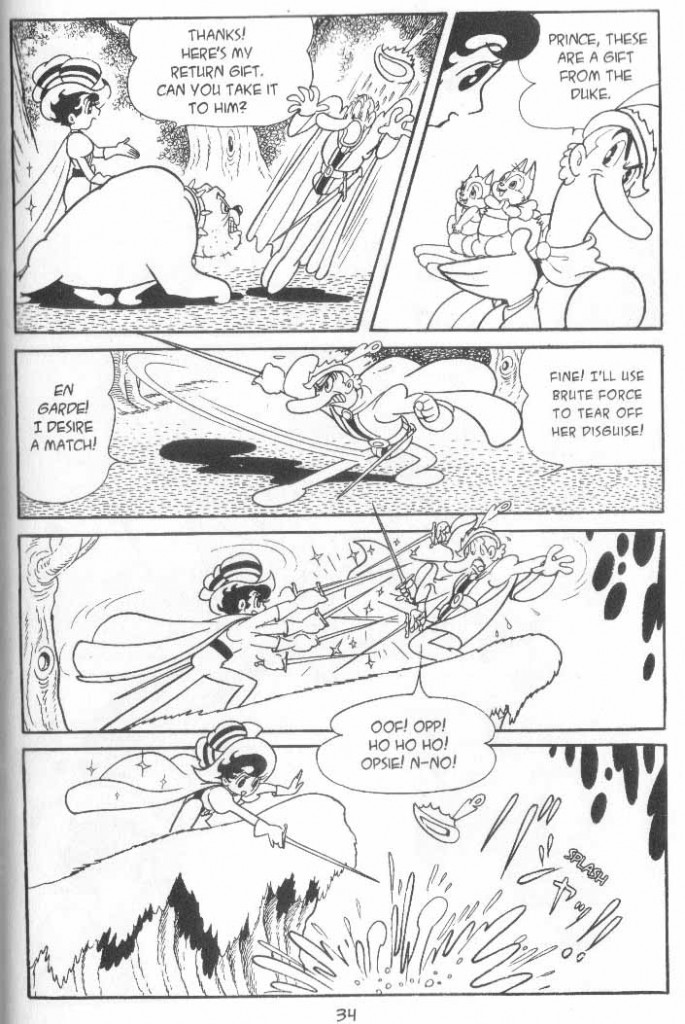

Early on in the story, Sapphire reacts violently to a series of entrapments by a deceitful courtier who attempts to expose her femininity through a woman’s “natural” passions for sewing and cuddly animals.

Yet it is the feminine calling of a beautiful gown that she secretly yearns for.

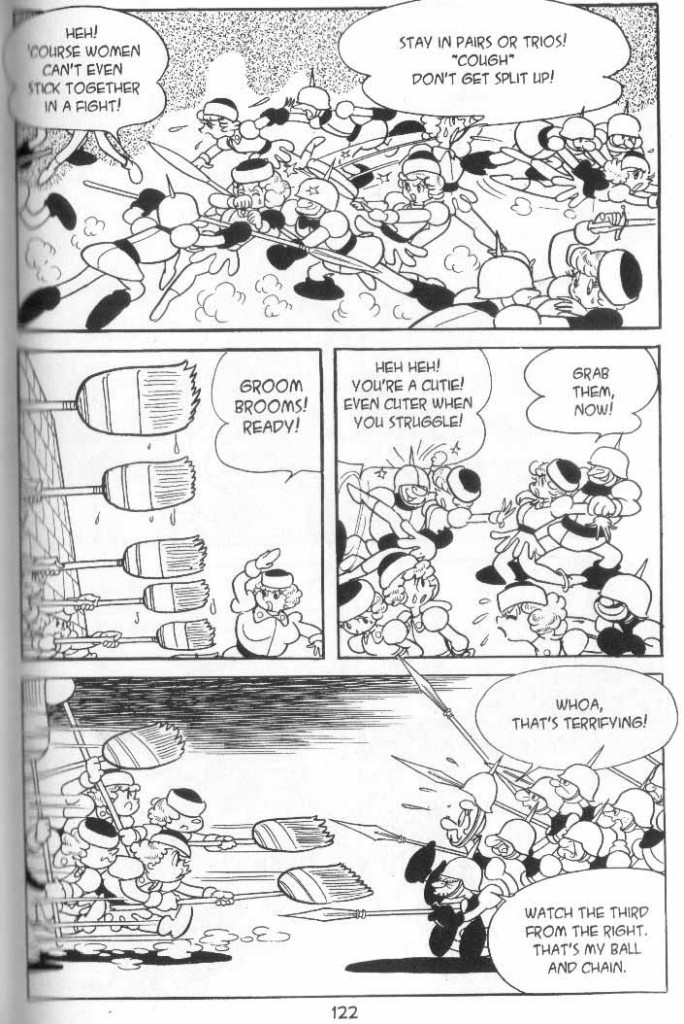

In many ways, Tezuka is less interested in gender identity (as a crossdressing protagonist would seem to imply) than in a kind of old school female empowerment. Unlike other fairy tale princesses, Sapphire drops a knife and not glass slippers. She is always “correctly” and heterosexually attracted to her prince charming and the aforementioned lavish dresses, yet fully capable of defeating her opponents in single combat — an antediluvian Lara Croft without the pneumatic breasts. The 6th century Ballad of Mu Lan had similar concerns but less reservations about the strength of women.

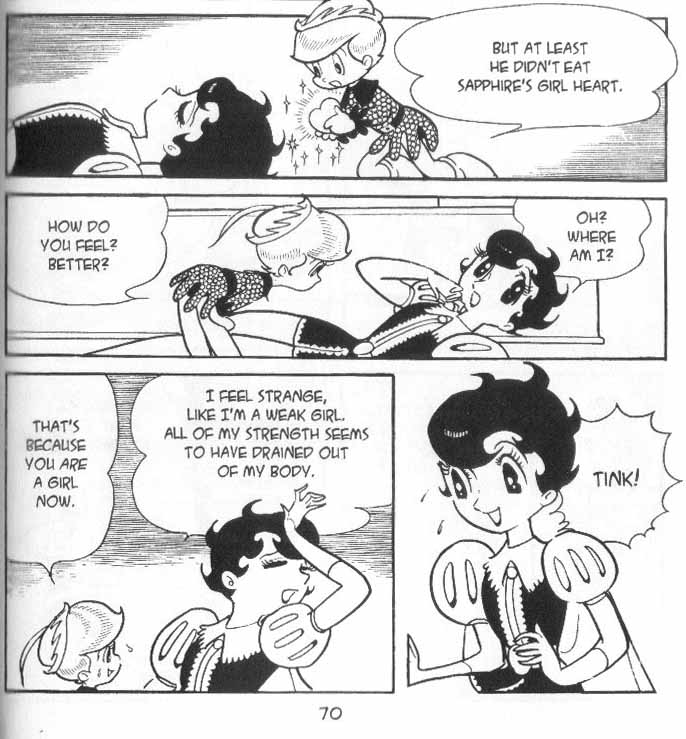

It is only in the second volume of this new translation that Tezuka begins let his guard down. When Sapphire’s female heart is extracted by the nefarious Madame Hell, she struts around in male fashion and rejects the advances of her prince lover. A more conservative approach is adopted when her angel guardian reverses this magical surgery and replaces her male heart with a female one — she becomes a wilting flower…

….a stance Tezuka swiftly dispenses with in light of his mildly feminist agenda. What’s an adventuring heroine to do if she can’t wield a sword? Even the emancipated ladies of the court use brooms to engage some invading soldiers.

Despite its long standing tradition of being the castrato of the comics world, North American comics have had an endless fascination with the transgendered lifestyle. Many of these are almost monkishly respectful while others posit rape as the first instinct of a male-female body swap (see Skin Tight Orbit; an erotic fantasy written by Elaine Lee). The latter device is a common trope in transgendered pornographic fiction.

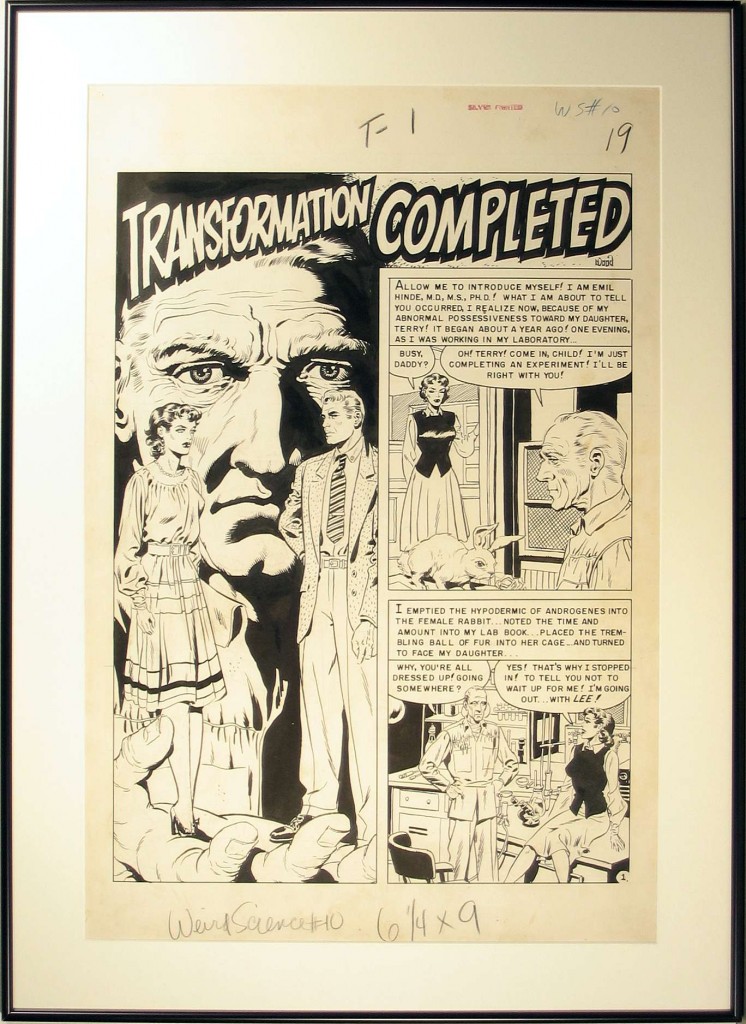

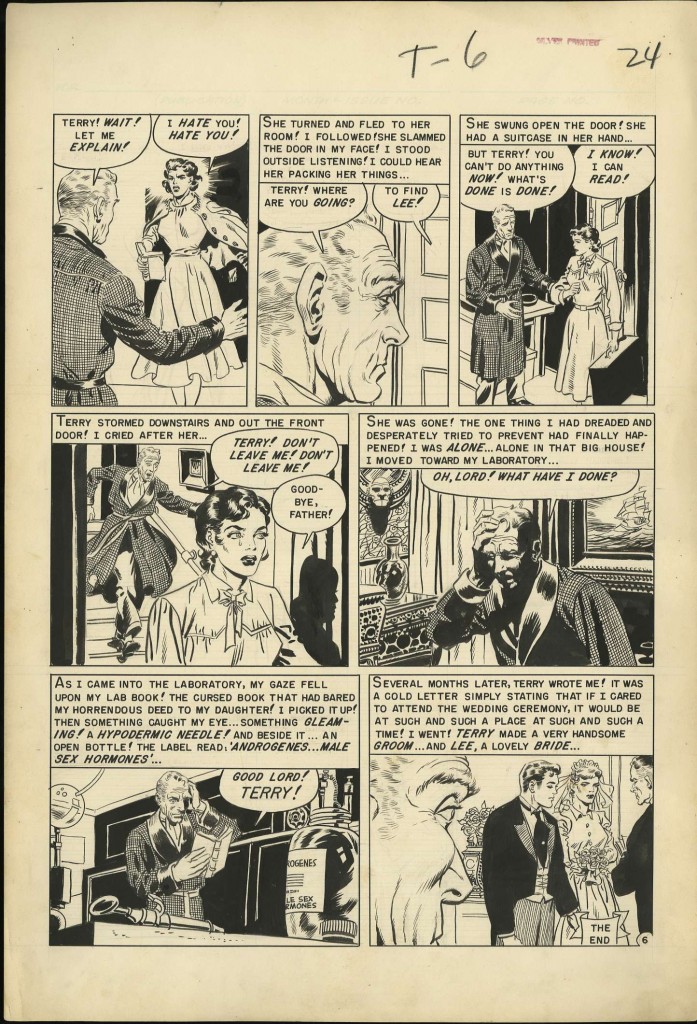

The transgendered stories surrounding Superman are perhaps the most entertaining from a historical perspective, but the canonical text in the genre must be Al Feldstein and Wally Wood’s “Transformation Completed” (Weird Science #10, 1951).

Here the unwitting fiancé of the female protagonist (androgynously named Terry) is transformed into a woman by her jealous father. Two constraints are at work here. Firstly, the bugbear of the homosexual lifestyle which can never be in a children’s comic and, secondly, the EC line’s own penchant for the “shock” ending. Both of these factors ensure that mere lesbianism will never be an option as far as the couple’s fortunes are concerned. On the final page of the story, Terry injects herself with her father’s gender change drug and becomes the groom to her newly female bride.

This kind of slow, forced feminization and simple gender reversal is a mainstay of transgendered literature (pornographic or otherwise), and satisfies both male-to-female and female-to-male desires and fantasies. We can see something similar at work in the operative female perfection achieved in Almodovar’s forced feminization horror-fantasy film, The Skin I Live In. Here the possibility of a lesbian romance is held up as the final shred of hope after years of sexual abuse at the hands of Antonio Banderas’ surgeon-torturer.

Needless to say, Tezuka will have no truck with any of this. The manga is question is for kids afterall. The taboo of abandoning the straight and narrow of the female lifestyle is suggested by no less than a minion of Satan (Madame Hell) and is rejected outright. [Sidenote: the female reincarnation of Tristan in Barr and Bolland’s Camelot 3000 is offered a similar bargain by Morgan le Fay but finally opts for lesbian love with her Isolde]

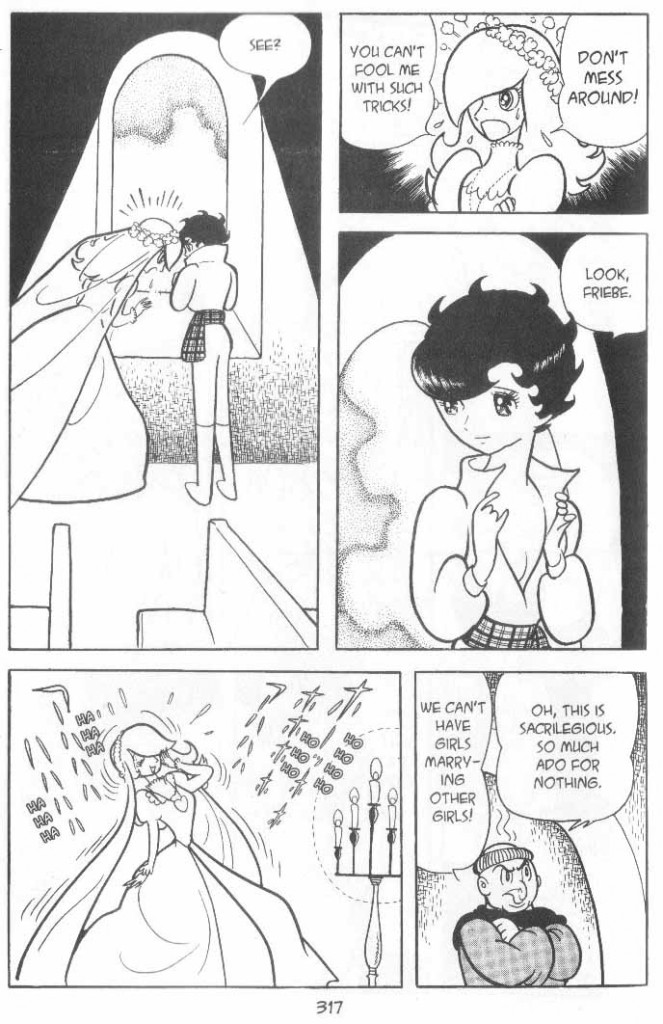

Readers prone to detect the lesbian frisson in the performances of the Takarazuka revue (said to be an influence on Princess Knight) will be left bereft by the heterosexual mores and desires of the protagonists in the manga. Sapphire’s potential bride (as seen in the penultimate chapter of the series) is left weeping at the altar once she is apprised of her groom’s substantial bosom; a Shakespearian moment further emphasized by the translator’s choice of priestly complaint (“Oh, this is sacrilegious, so much ado for nothing.”)

Considering its worthy progenitors in the field of literary transvestism, one might say that the most surprising aspect of Princess Knight is not its crossdressing heroine but the author’s need to contrive a celestial accident for a woman to be skilled at athletic and martial activities. What little “feminism” we see on the page soon gives way to escapades not dissimilar to what you might find in the adventures of Zorro, The Prisoner of Zenda, or a movie starring Douglas Fairbanks. One assumes that this presents an advance over the usual position of women in comics during the 50s and is to be commended.

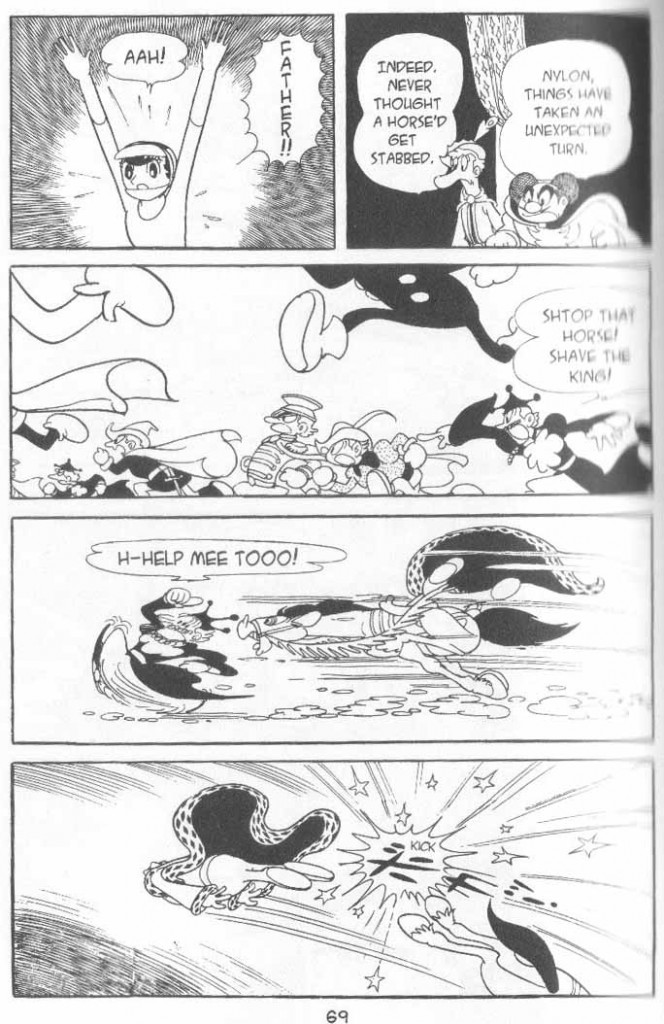

Nevertheless, this is a manga to be read more out of a sense of duty than anything else. Its historical importance as far as manga directed at girls is concerned is indisputable, but the romantic dilemmas on show are uninvolving. The tiresome and largely unimaginative plots will prove a chore for most. It is undoubtedly virtuous in intention but also averse to do away with childish things even if only for a moment — a product of its time with all the limitations that implies. Nowhere is this more clearly seen than in the death of Sapphire’s father which is not so much a terrible moment (see Bambi or Charlotte’s Web) but a simple plot development and an exercise in frantic cartooning.

There can be little doubt that Princess Knight remains a perfect example of that safe, asexual entertainment people have come to expect from comics.

That Wood artwork…sure looks like Orlando. From the time when Orlando was his assistant, I presume…

I’ve really yet to see any Tezuka that I find even remotely interesting…I’d sort of hoped that I might like Princess Knight, but this seems pretty dreary.

Noah, wouldn’t you have to admit that the limitation there might be yours rather than Tezuka’s? Can the millions who find Tezuka a very interesting (if not genius) creator all be off base? I’m just saying … This is an interesting discussion of a work I obviously find much more rewarding: the note that this comic’s limitations may be due to a presumed child audience is only valid up to a point: there’s much more to say about its cultural and historical context: keep in mind that even in contemporary Japanese pornographic films (pinku eiga), no one has genitalia either …

Noah: Recently weeding my collection, I ended up getting rid of all my Tezuka except Phoenix and Adolf. Phoenix is at times inconsistent, but I think some of the volumes are Tezuka’s best work. They seem to show him working outside both the “children’s” style (a la Princess Knight, Astro Boy) and the “adult” style (Kirihito, Ayako, MW) that most of his works fits into. Rather they are just telling the story without being simplified or being pumped up with extra sex/violence (which sadly with Tezuka are often closely intertwined in those “adult” works).

Yeah, Suat, this was a slog to get through — and I like a lot of Tezuka’s work. The final sections, in particular, drag, coming as they do after a natural denouement; they really feel like serialised padding. Still, the series isn’t entirely without interest: Tezuka’s Disneyfied appropriation of the kitschier parts of folk Christianity is amusing. Well, I was amused, anyway.

Also, am I imagining things, or is Tink the direct ancestor of Link, from the Legend of Zelda video games?

Corey, millions of people liked Friends, which I found godawful. Millions and millions of people voted for George Bush, who I didn’t like either. I don’t find arguments from aggregation especially convincing.

I don’t hate Tezuka or anything; what I’ve seen is definitely superior to Friends or George Bush. I’ve just yet to see anything by him that really excites me.

We’ve actually got a post coming up about the argument from popular authority, though, I believe…so tune in next week as they say….

Noah: “I’ve really yet to see any Tezuka that I find even remotely interesting…”

Ditto.

Corey: Ah yes, I certainly failed to see the connection between Japanese porno and Princess Knight. But there must be a connection there. The thing is, they don’t even mention the possibility of examining genitalia in Princess Knight.

Derik: You kept Adolf? That’s a pretty bad book. As far as “adult” Tezuka is concerned, I’d rather keep Buddha or just stick with Phoenix. I probably prefer Mighty Atom to Adolf actually (haven’t read either in over a decade).

Jones: I suppose the Disneyfied Christianity in Princess Knight does have a train wreck kind of charm to it. It was mentioned by quite a few of the reviews I read and not always in a negative sense. Strangely enough, the weight of North American opinion doesn’t seem to be wholly on the side of Princess Knight. It’s usually pretty positive when it comes to Tezuka.

Yeah the Christian stuff in Princess Knight was interesting. When he uses Madame Hell and has her as a devilish figure- it sort of brought home the fact that Disney is remarkably secular in contrast.

Which raises questions as to why it’s ok to use Christianity as a plot device in a vampire story, but it feels so off for a Disney-esque villain to be repelled by a crucifix in a similar manner to a vampire?

Suat: Oh, I forgot I kept Buddha too (which is my favorite after Phoenix). Adolf… I’m not sure why I kept those, honestly. It’s just one I haven’t had a chance to reread in awhile to see. (I recently reread a lot of the others, which prompted my weeding of them.)

Pallas: I don’t know about Disney being that secular. The closing sequences from Fantasia are pretty damn religious (Night on Bald Mountain and Ave Maria I think). On the basis of Princess Knight (and other early works), Tezuka seems to have only got as far Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony. I’m not saying the 2 sequences are awesome or anything like that, but they’re more religious than anything I’ve seen from Tezuka. I think you can find deeper religious feeling in Tezuka when it comes to Buddhism and reincarnation (as in Phoenix).

I think the crucifix repelling thing in Princess Knight is the very definition of kitsch. It’s a frankly uninvolved, unfeeling inferior copy. I’ve seen some TV adaptations of Dracula which are rather invested in the whole religious schema. That’s the difference I think (that and tradition).

If memory serves, there’s a good dose of Christian themes in Ode to Kirihito, where they’re handled a little more seriously.

I really enjoy that manga thing of using Christianity as just one more source of crazy fantasy imagery (see also: Evangelion). It’s like how Europeans have been using e.g. Graeco-Roman and (more recently) Norse religious beliefs for centuries

Yeah, but at least for Evangelion you can say (without too much tongue in cheek) that there’s complexity and conviction in the Christian imagery. And like any religious conspiracy theory, it helps that it doesn’t make much sense.

Luis Buñuel said that Catholicism is completely Surrealist.

Haven’t seen Fantasia.

Evangelion may have “conviction”, but I’d say it’s not conviction in any religion that any human being has every practiced.

Definitely a bit of a mishmash – Judaism, Christianity, Kabbalah. Maybe a bit of conspiracy theory and cultish thinking a la SF-Scientology. I’m sure someone out there practices something like this. Maybe the love child of Madonna and Tom Cruise?

Pingback: Comics A.M. | Archie co-CEO talks Kevin Keller marriage, boycott | Robot 6 @ Comic Book Resources – Covering Comic Book News and Entertainment

I wasn’t suggesting that “majority rules” in questions of taste or preference: just that what I find unconvincing within the context of criticism is the individual’s assertion of lack of interest, presented as a critical judgment rather than an admission of a possible blind spot. Such assertions always seem to me to finally reduce to the tastes of the single person, not the quality of the work being evaluated. What gets opened up for question is what the critic requires to be interested, not what would make the text itself interesting. I’ll admit I’m a perverse teacher in this regard: when students tell me something bored them, I announce that this is a chance to examine their criteria for finding something interesting, and then the social and cultural basis for such criteria … so I’m finding dismissals of Tezuka’s work more about the critics than the work at this point: and wondering if it is surprising that some men aren’t crazy about a manga most famous for addressing and attracting young female readers.

…but notably written by a man in the 50s for young Japanese girls. I think I’ve read 1-2 interviews where modern day female mangaka have commented respectfully but somewhat negatively about “shoujo” stories from that era (haven’t got them indexed for reference though).

But, Corey, what if the thing that they were disinterested in was Britney Spears? Or Twilight? Or television advertising? Surely the issue is that Tezuka is critically validated (and/or that you like him), therefore you’re willing to dismiss those who don’t find him interesting as aberrant?

Suat provides fairly clear criteria as to why he’s not that into Tezuka. The plots are cliched, the transgender play is very circumscribed and not especially adventurous. Those seem like convincing criticisms to me, and fit with my own past reading of Tezuka, which mostly suggested fairly pedestrian genre fare.

Any aesthetic judgment is going to be about the person making the judgment *and* about the work in question. Suat’s taste is subjective, but he also does a good job of explaining why the initially possibly interesting trangender nature of the work is actually quite banal. I’m often interested in work that bends or questions gender (like Marston’s Wonder Woman or Edie Fake); I think Suat does a good job of explaining why this is not that. As such, his subjective take is relevant to a broader audience (or at least to me.)

I’d be interested in hearing why you think Suat is wrong, or on what grounds you think the manga is worthwhile. But I don’t think it’s accurate to say that Suat merely provided a subjective opinion without any further critical insight.

“Phoenix” was a really weird Tezuka story. I didn’t read all of it though, so I guess that says something.

You mean you didn’t manage to get through even a single volume? That does say something. Weren’t the English language editions printed out of publication order as well? The usual advice is to try “Karma” first.

They did one out of order first in a larger version, but otherwise the only one out of order was one of the short ones (so they could combine into normal sized volumes).

There actually are some interesting sequences in Princes Knight. I’ve only read volume 1, but there’s a bit where Tink almost gets Saphire killed because he’s feminizing her with a flute (music makes her girly) which means the villain will be able to murder her because in the story girls can’t fight in battle.

What’s interesting is that he’s doing it based on instruction from God to make her feminine, and is basically disobeying God when he stops playing the flute to save her life.

It doesn’t tie into the overall themes of the story maybe, but that particular chapter is pretty interesting, and Tink tossing the flute into a river at the end of my favorite sequence in the book. The gender stuff is maybe a little more complex than Suat gives it credit for, at least occasionally… that said I don’t know how it ends.

I don’t think it would be too difficult to make some hay out of the things Tezuka does in Princess Knight. It’s just that those things didn’t work on me.

Tezuka actually does that feminizing “thing” at least twice more in Princess Knight. Once more in volume 1 and another time in volume 2 – the heart replacement procedure mentioned in the article. In the flute sequence, Tink asks “God” for help to complete his feminizing mission. Heavenly inspiration causes Tink to make a feminizing flute (though he’s not aware of this initially). The second time, he’s a more willing participant and attempts to suck the “masculinity” out of Sapphire. In this instance, he’s once again misled by “God” who allows him to think that time will stop and that Sapphire will not be in any danger. Instead, she’s placed in immediate peril by her arch enemy. In this second sequence, “God” accuses Tink of being too human and neglecting his duties as an angel.

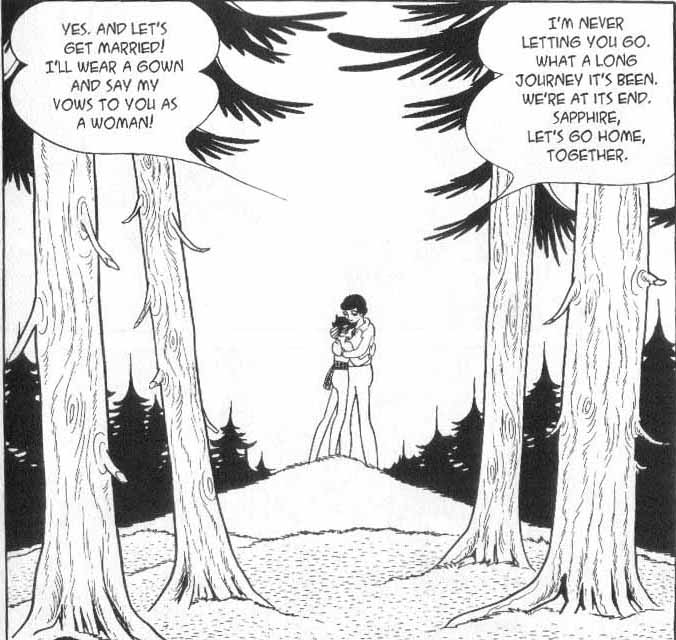

So you might say that “God” is a pretty shitty (largely disembodied) person in the book. You might even say “God” is a proxy for chauvinistic Japanese society (distant, loud, uncaring) which sees masculine traits in women as being aberrations. The ending (seen in the final image above) sort of reverses all of this though.

The criteria according to which the comics subculture values Tezuka are easy to list. Imagine the criteria most valued *outside* of the subculture and invert them.

Did you know Princess Knight has a sequel story? Vertical translated it too! Tezuka-sensei does away with the whole boy heart, girl heart deal and just has Princess Violetta (Sapphire and Franz’s daughter, twin sister of Prince Daisy… yes, Sapphire named her son Daisy xD) crossdress and battle because the situation calls for it: no need for a dual gender identity caused by angelic mix-ups.

It sounds vaguely familiar so I may have known once but not anymore! Is the sequel better than the original (or at least the crossdressing stuff)?

Did you really expect a Japanese comic from the 50s-60s to deal with transgender issues? Given the country and time it comes from, what we do see in its message of gender discrimination and gender roles is pretty advanced. That said, the sequel is better. Especially the ending.

Firstly, I agree almost entirely with the content of this article. But I want to add my view of Tezuka to this mix. The disparity of the above comments starts to identify why I love Tezuka; it’s because he’s a madman wearing a Disney diguise. I was initially drawn to his naive feeling charm and obvious influence on modern world culture, but I found myself feeling repeatedly uneasy with varying moral messages. Gender issues were often involved. The toying of childhood with female maturity was bothersome (Pinoko and Melmo specifically). Blackjack’s college lover who apparently ceases to be a woman capable of heterosexual love once her uterus and womb are removed. Very off-putting. But I’ve learned to accept those flaws and enjoy the ride. In comments above he is accused of both Christian and Buddhist morality. He even did a series of Bible stories, when asked. Tezuka PRO sells his material as preaching a message to “Love all things”… But frankly, rampant existential nihlism is also pervasive in his view of civilization. Phoenix shows mankind never escaping the wheel of suffering, mired in it’s own greed and destructive nature from beginning to end! Wonder 3, Bird Anthology and many smaller works are about humanity being judged by the universe (not God) for it’s many evils. So, what is he saying?? My theory is that he himself rarely knew for very long…

I may get these figures wrong, but Tezuka is famed for creating 700 volumes over 150,000 pages, of which the West has sampled very little. Gratuitous violence and sex. Corny pablum. Great cleverness. Random nonsense. Weak plots. Genius concepts. It’s all there, and often beside one another. His work is prolific and frequently ‘off the cuff’. I think his moral message is the same, and subsequently not very cohesive. I stopped worrying about his grand message, and just started enjoying the unpredictable creative maelstrom of uneven quality and contradictory morality being forced through his doe eyed star system. We don’t like to shrug when analyzing somebody of such relevance, but I feel like he gives little other option.