In Part I, I discussed the Freudian model of fetishism, phallic mothers, and their importance to Gilbert Hernandez’s Poison River graphic novel. I’ll wait here if you want to go read that piece of mindbending wisdom. Waiting…waiting… Welcome back!

________________

What the preceding has to do with the Locas roundtable, or Jaime Hernandez’s work more generally, may seem a bit distant, but it all links, fairly directly, to the primary theme of the roundtable thus far: nostalgia. Jaime’s works function nostalgically, or seem to, and are frequently about nostalgia (however one wishes to define the term) and the traffic between past and present. Freud’s account of fetishism is, in fact, an account of nostalgia as well…nostalgia for the phallic mother…nostalgia for that originary moment before knowledge of sexual difference, and before the traumatic fear of castration.

The phallic mother represents a “perfect” time, a time of wholeness and unity in a number of ways. First, it is a time when mother and son are still joined together without the interference of the father. While the child may be aware of the competition with the father, he has not yet given up the notion that he will be forever joined to the mother and that their blissful union will be eternal. It is the threat of castration that frightens the child out of these utopian beliefs, at least for boys, but the attachment of desires to the fetish is an attempt to retain such a utopia, to hold onto this perfect past even after it is already gone. To fetishize a shoe (or an athletic support-belt) is to cling to the past with the mother, and to be “nostalgic” for it.

Second, the phallic mother represents a complete and ideal “whole” human being, who has both breasts and a penis, the complete and unified being the boy imagines his mother to be before the revelation of her (and the prospect of his own) castration. When the child learns of sexual difference, he learns that none of us are “whole.” We are one gender or the other, but never both, and so, it is “natural” to reminisce and to feel “nostalgic” for such an ideal wholeness even as one pursues a replacement for it in the field of romantic love.

Again, there is no reason why we must believe in the narratives Freud provides, but it does provide a useful heuristic for understanding Jaime Hernandez’s work as well and especially the stories collected in La Perla La Loca (which includes the graphic novel, Wigwam Bam and the stories which follow). Perhaps most central and helpful in looking at these stories is the central truth of these Freudian narratives, which is that “nostalgia” here is never nostalgia for something real, but is instead nostalgia for a fantasy of wholeness which never existed. Simply put, of course, the boy’s mother was never an androgynous whole with both a penis and breasts. This is, of course, merely a fantasy the boy has (or a fantasy Freud has and projects upon the boy in his story). Likewise, the mother was never castrated. Rather, she never had a penis from the beginning. Similarly, the boy never had a direct, unmediated, love affair with his mother uninterrupted by the father. Again, this is simply an Oedipal fantasy that serves to structure the boy’s psyche, but has no basis in reality. A fetish, then, is a replacement for something that was never there in the first place, a replacement for the female phallus that Peter Rio (in Poison River) searches out, but which was never present in his own mother. It is this model of replacing an absent original that is central to Jaime Hernandez’s work in general and Wigwam Bam in particular, and which helps explain the peculiar “emptiness” at the center of his nostalgic forays.

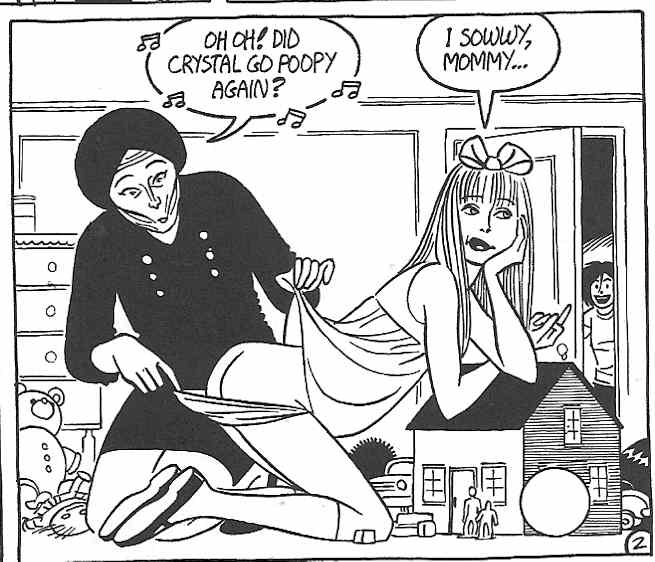

As evidence, it is perhaps worth recalling one instance of explicit sexual fetishism in Wigwam Bam, which occurs when Hopey spends a brief period couch-surfing with her friend, Jewel, in New York, after leaving another friend’s apartment. Jewel’s mother, Nan Tucker, has her own peculiar fetish, which rivals Peter Rio’s. While not fixated on a particular object, Nan pays a young woman, Crystal, to dress up as a much younger girl, and pretend to be her “baby,” allowing Nan to change her diaper, and role-play similar activities. In fact, as it turns out Nan organizes gatherings of famous TV sit-com mothers (of which she is one) who have identical fetishes and who bring their own “wards” with them. While conventional sex itself never seems to be in play in these relationships, and the girls are paid well to act their roles, the scenario certainly plays out in fetishistic fashion, particularly given the Freudian material cited in Part I.

The TV moms’ fetishization of youth encapsulates a similar kind of “nostalgia” to the kind that Freud discusses, if somewhat in reverse. Nan nostalgically attempts to recapture her own youth, both as a young mother, and as a child, paying Crystal to “act out” the wholeness and unity of mother/child relations that are central to the Oedipal scenario (if, in Freud, usually from the point of view of the child). Given Nan’s vexed relationship with her own daughter (whom she competes with for Hopey’s affection), like Freud’s version of the fetish, Nan here is nostalgic for something that never existed. With Crystal, there is an ideal union with a daughter who will always be young and obedient (because paid to perform that role), as opposed to her real daughter who is now an adult and disgusted by her mother’s behavior. In fact, it is strongly implied that these women’s entire careers on television, as sit-com mothers, is already a replacement for their own failed relationships with their daughters, and the young women they hire serve as replacements for the replacements…second order fetishes that help them to convince themselves of the original’s existence (while also disavowing it).

Here, Jaime provides a broad satire and mockery of a nostalgia for innocence and childhood, which belies the notion that Locas itself represents a simplistic foray into such nostalgia. Instead, via the logic of fetishism, Locas suggests that any such nostalgia is a longing for an absence, whether it be the mother’s phallus which never existed, or a perfect mother/child relationship that can only be simulated in sit-coms or by hiring a child not one’s own.

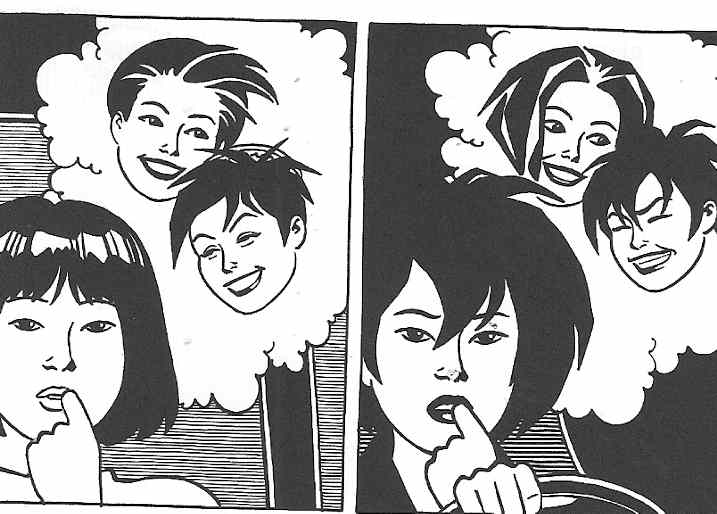

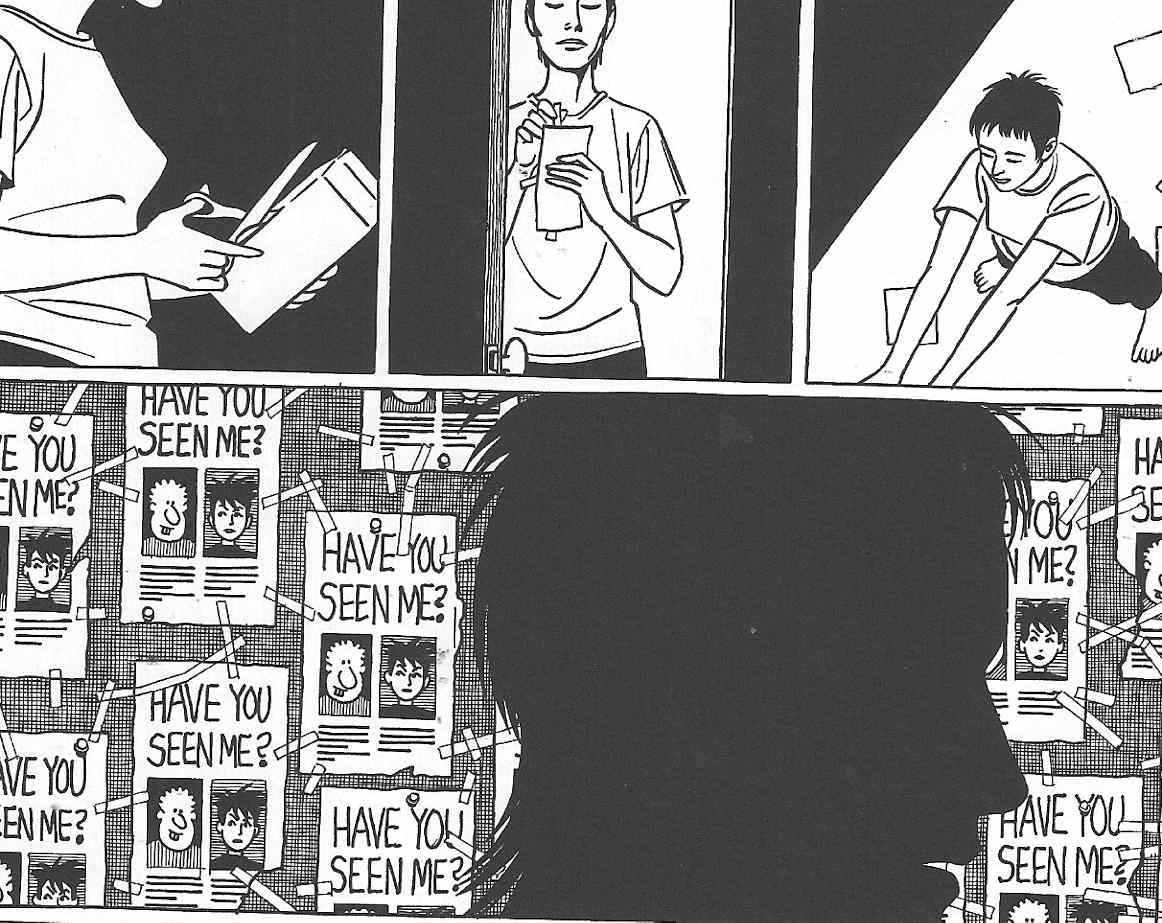

Nan Tucker’s nostalgia and desire for a perfect, originary moment of wholeness is not an isolated incident in Wigwam Bam, but is rather a synecdoche for its entire workings. As Douglas Wolk notes in his reading of WWB, perhaps the most clever formal trick deployed in its pages is the strategic absence of Locas’ most central character, Maggie Chascarillo (known also as “Perla” in the book in question). Apart from the first 14-page section of the 115 page graphic novel, Maggie does not appear in WWB and so the reader takes place in the grand search for her that is also enacted by its characters. In particular, Maggie’s childhood “punk” friends from Hoppers, spend the story looking for both Maggie and Hopey, who have traveled to New York (one in pursuit of the other). Izzy Ortiz, in particular, dealing with mental health issues of her own, becomes obsessed with the absence of Maggie and Hopey, cutting out the backs of milk cartons which picture Hopey in “Have You Seen Me” mode and taping them to her walls. Eventually, Izzy’s obsession with the missing Maggie and Hopey leads her to travel the country in search of the two friends, meeting up with a variety of Locas characters along the way.

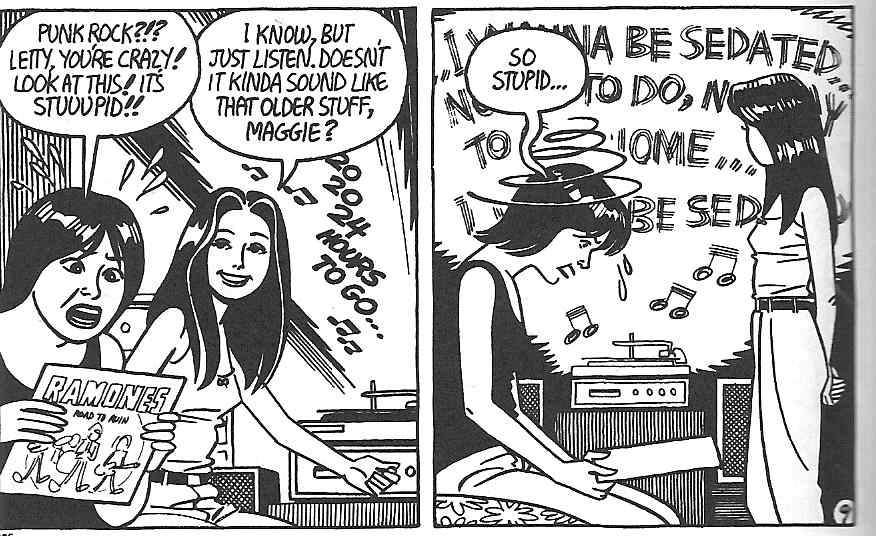

Here again, Izzy’s search is clearly an act of nostalgia. For Izzy (and Daffy, and their friends), the friendship (with benefits) of Maggie and Hopey represents a prelapsarian utopian paradise that is linked to the punk culture of which they were all a part. The punk community of their youth, or the women’s imagined vision of it, rejects dominant culture’s series of hierarchies and divisions, including those of race, gender, class, and sexuality. The punk community’s rejection of consumerist/corporate capitalism is well-established, but the concomitant image of an angry, loud, violent opposition is largely eschewed in Locas, in favor of an image of a community which is accepting, multi-racial, gender-equal, and open to non-heteronormative sexualities. Maggie and Hopey, in particular, represent both the rebelliousness of the Hoppers punks (particularly in Hopey’s case), but also its friendly, open, and forgiving face (particularly in Maggie’s case). Their lesbianism (or bisexuality) is open to interpretation but is never censured or rejected by their fellow punks, whether male or female (many of whom are also “queer.”) The blurring of gender divisions, and therefore heteronormativity, is, as discussed in Part I, part and parcel of a hearkening for the pre-Oedipal, a time before such divisions are known. The Maggie/Hopey relationship (or the memory of it) serves as a fetish for Izzy, who desperately tries to track them down and regain the utopian promise of Hoppers in its younger, punkier, days.

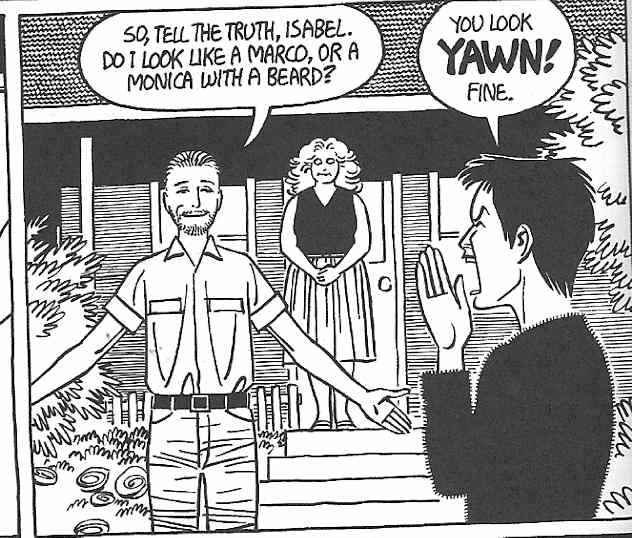

It should be no surprise, given these thematics, that among the individuals Izzy finds on her journey are both a Maggie lookalike (an explicit replacement) and a “phallic woman” from her own youth, a woman who has undergone a sex change to become a man. Likewise, it is not surprising that this “real” phallic woman fails to hold the attraction of the utopia Izzy has imagined. S/he is a failed replacement for Maggie/Hopey, just as Peter Rio’s strippers are failed replacements for his (phallic) mother.

By the time Izzy finds Maggie and Hopey, of course, they are no longer “together” despite their earlier efforts to reunite. In fact, their brief blissful attempt to reignite their friendship and recover their youth is sabotaged by the racial difference that is rarely of explicit emphasis in the previous stories that take place in Hoppers. When Maggie is mocked at a party for being Mexican, she seeks solace in Hopey, who is less than sympathetic. When it becomes clear that Hopey, who is half Colombian, can “pass” for white, a racial divide opens between the two women that, perhaps, had previously existed, but which had gone unmentioned. Hopey’s casually homophobic reference to “art fags” (despite her own sexual orientation), further cements the ways in which the nostalgia for the “perfectly punk” Maggie/Hopey relationship is misplaced in “real world” New York, which, despite its cosmopolitanism, is rife with racism and homophobia.

Indeed, later in the story, we learn that the Maggie/Hopey relationship is itself merely a replacement for, or copy of, Maggie’s first “punk” relationship, with her best friend Letty, who introduced her to punk music before dying in a car crash. In a telling diary entry, Maggie writes, “I hope Hopey never dies in a car crash. Lightning only strikes twice once, y’know” (115). Hopey is here explicitly framed as a “replacement” for Letty, a fetish which covers up an absence, while attempting to replace the “wholeness” of the Maggie/Letty relationship, though Maggie worries that the replacement itself cannot be replaced.

Within this context, Ray D, Maggie’s next serious relationship (one which “culminates” in the recent Love Bunglers arc), serves as a replacement for Hopey, who herself is a replacement for Letty. Within a Freudian logic, Letty can only be a replacement for the mother (or the mother’s phallus), and Maggie’s expulsion from the maternal family home to live with her Aunt Vicki in Hoppers as a youth might substantiate such a reading. At the same time, the important point here is that regardless of the idealization of the Maggie/Letty relationship, it is clear that such idealization is a mirage, a hope for something which, like the mother’s phallus, never existed to begin with. The Hopey/Maggie relationship is, after all, similarly idealized, but is revealed to have many cracks in its façade.

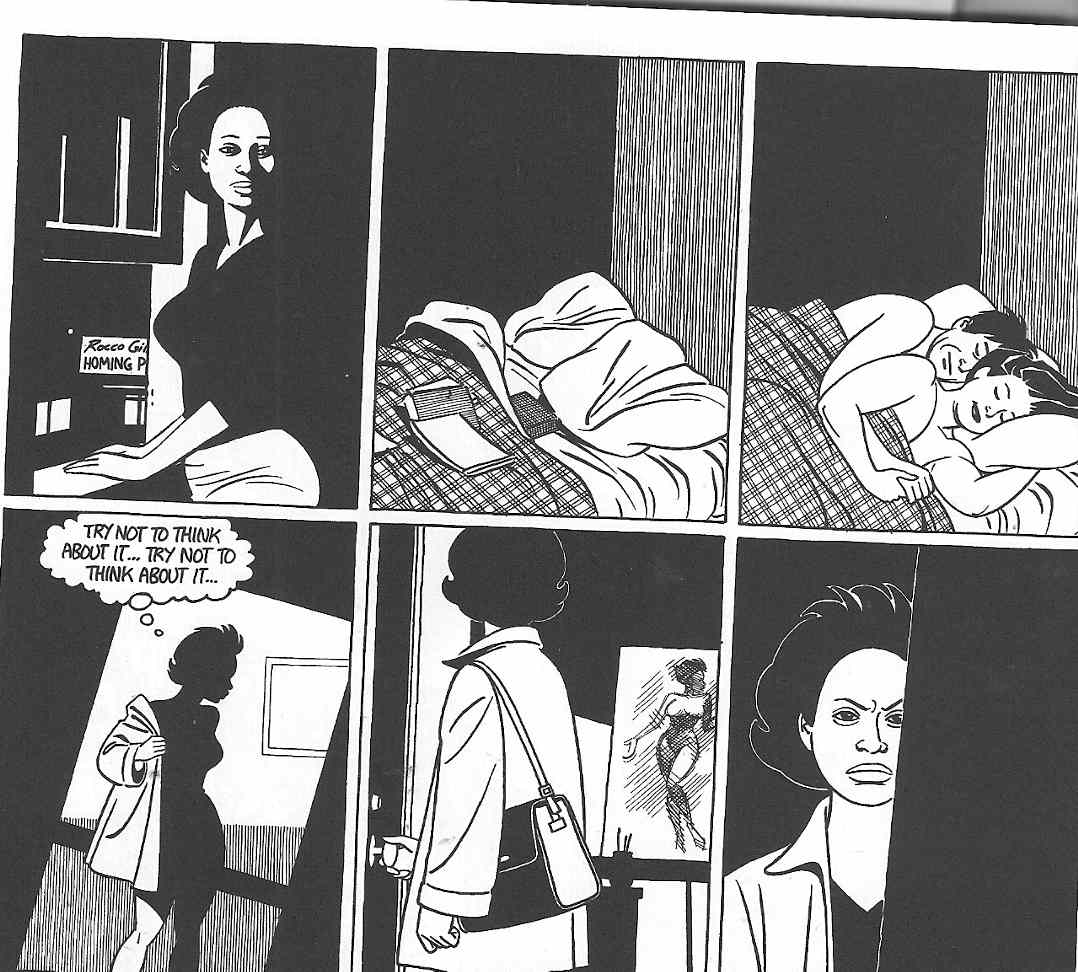

Similarly, Ray D.’s relationship with Danita Lincoln is characterized as a replacement for his earlier affair with Maggie. In particular, Danita’s confidence in the level of Ray’s commitment vacillates. She worries both that she is merely a “sex object” for Ray and that he cares not for her as an individual, but as a Maggie substitute, even going so far as imagining Ray in her own bed, cuddling with his ex-girlfriend. Danita’s fears about her own “fetishization” (her transformation into a sex object and Maggie replacement) is played out in multiple scenarios. She serves as a nude model for Ray’s drawing/painting and as a stripper at the local club, Bumpers. Her friend Rocky suggests that Ray sees her only as an object, when looking at Ray’s drawing, as if he were one of the members of the strip-club audience. At that moment, Danita, who had initially been flattered by Ray’s appreciation, begins to wonder to what degree she is just a body, filling the space recently left empty by her predecessor. Likewise, where she once saw her stripping as an empowering experience of agency, she now begins to see herself through the eyes of her audience, as one of a procession of naked bodies on a stage, objects which occupy the same space, replacing each other at regular intervals.

In this scene, Wigwam Bam examines itself as well. Ray too becomes a replacement of sorts, not only of Hopey in Maggie’s life, but also of someone “real,” Jaime Hernandez himself. When Rocky accuses Ray of objectifying Danita, it functions as Jaime Hernandez accusing himself of objectifying her, and his other female characters for good measure, for it is he who really draws naked pictures of women, both for his own pleasure and that of his mostly male audience. Again, as in the case of his brother, Gilbert, the fetishizing and objectification of women is here brought up against a moment of self-examination and an acknowledgment that from Danita’s point-of-view, she cannot merely be a body for the pleasure of the male gaze or a simple replacement for the superior/utopian relationship that preceded it, even if that relationship never really existed in its ideal form. Danita’s self-conscious worry is, indeed, a sign of her subjectivity. Her vulnerability and determination make her in some ways similar to Maggie, but far from identical to her. Her assertion of her own subjectivity is a tacit critique of the practice of fetishizing people, of transforming subjects into (replacement) objects for the purposes of sexual pleasure, and it comes as no surprise when she leaves Ray, a tacit rejection of her objectification at both his, and Jaime’s hands.

The encounter/conflict here between Danita-as-object/replacement/fetish and Danita-as-subject/original here sets up the ways in which WWB and its immediate sequels take things a step beyond the fetishism on display in Poison River. In Poison River, there is a focus on fetishism-as-utopian-fantasy and then disillusionment with that fantasy. That is, the fantasy of reunification with the phallic mother is revealed to be a fantasy and the book closes on a note of disillusionment where everything is corrupted, gender divisions are enforced, and a bloodbath ensues. In the Perla La Loca stories, simple disillusionment is not enough, however, and Jaime pushes the narrative forward into a more “realistic” engagement with utopian premises.

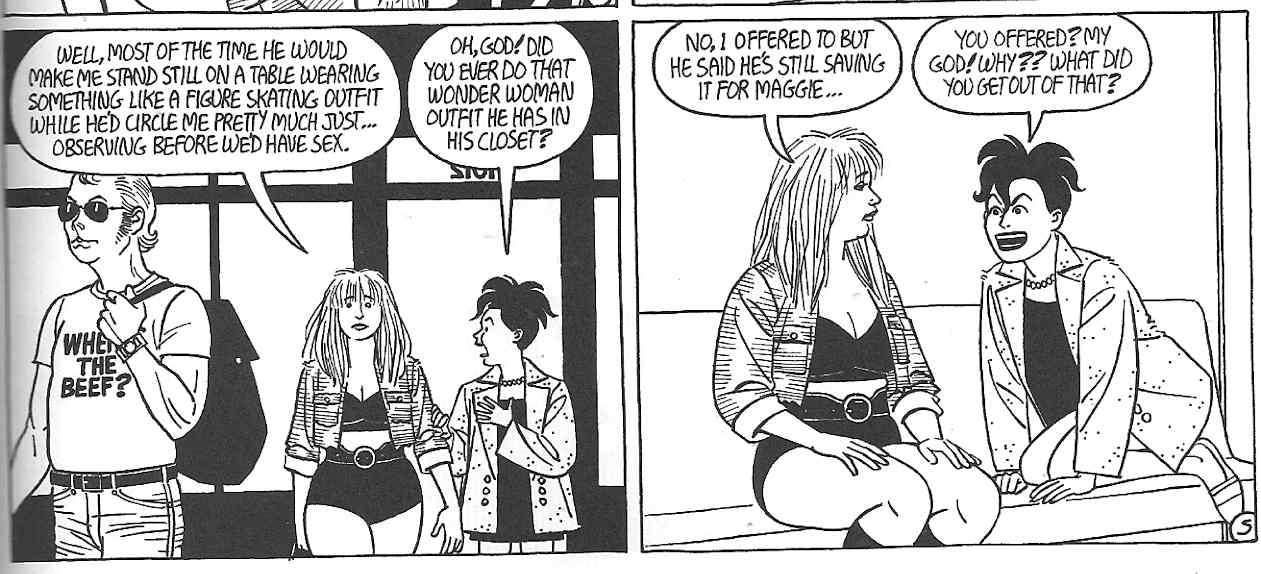

As Danita’s introspection suggests, while “fetishism” may, in some ways, envision a utopia wherein gender divisions, racial divisions, and divisions on the basis of sexual orientation do not obtain, they do so on the basis of a backward-looking fantasy to the pre-Oedipal. In such a fantasy, no individual in the present is fully acknowledged or accepted for their own sake, since they are always inevitably viewed as a replacement for someone else. As we have seen, Hopey functions as a replacement for Letty (and Ray for Hopey), while there are also a seemingly neverending series of Maggie replacements as well. In addition to Danita, Marcia/Marco, and the Maggie lookalike, we learn in “We Want the World and We Want It Bald,” for instance, that Hopey’s brother Joey’s girlfriend, Janet, is also a Maggie replacement, and plays a role in the sexual fantasies/fetishes that Joey inflicts upon her. In all of these cases, however, if one reads the stories “realistically,” as opposed to merely as an instantiation of Freudian theory, the danger arises of reading individuals as merely replacements for one another, as “fetish objects” as opposed to as autonomous subjects.

In fact, Jaime uses the pervasive theme of replacements and fetishes in order to probe and reject the tendency we all have to use people in our lives as “objects” for our own pleasure (fetish objects), as opposed to as subjects with autonomy. Danita may function as a replacement for Maggie for Ray (though this is somewhat questionable), but for herself she has autonomy. Likewise, Hopey wonders what Janet “gets out of” her fetishized relationship with Joey, when she seems to serve merely as a stand-in (again) for Maggie. Even Maggie herself is in danger of falling victim to a kind of objectification if we are content to view her simply as a “symbol” of phallic motherhood (a figure that remains an idealized symbol of wholeness, unity, innocence, and purity), and not as a complex, fallible individual.

This theme of objectification plays into Locas’ parallel exploration of the problems of capitalist culture to which punk is configured as an alternative. As Marx notes in The Communist Manifesto, capitalism reduces all relationships to “the money relation” (659), wherein individuals view other individuals not as human beings (subjects), but as a means to their own acquisition of wealth (objects), a weigh station on the way to the acquisition of capital. It is for this reason that Marx can articulate the existence in society of “commodity fetishism,” in which people put outsized importance upon specific commodities. If money is the only value in society, it should be no surprise that “pleasure” can only come from them. If one combines Freudian and Marxist logic, then, to fetishize a commodity (or object) is both to imagine a world wherein there are no divisions (and therefore no exploitations) and to value a world wherein those exploitations are inscribed upon the very object being fetishized. As a “replacement” for the phallic mother, the fetish object symbolizes a perfect “whole” world devoid of divisive qualities, while, as a commodity, it carries the trace and history of endemic class exploitation. The contradiction brings to our attention the limits of thinking through the logic of Freudian fetishism. While, symbolically, the “objectification/fetishism” may represent a challenge to the race, class, and gender divisions in a society, in social practice, to treat an individual as an object/fetish is to treat them, á la Kant, as a means to an end, as opposed to as an end in themselves.

All of this is clear in Danita’s rejection of her role as Maggie’s replacement, as well as in her eventual rejection of her role as a stripper. The stripper role is complex in the story, as Danita clearly feels like it gives her agency and power, but even though this is the case, it also positions her as the object of the male gaze, a position she is increasingly uncomfortable in occupying. In either case, however, it is interesting that, despite her role as the object of the gaze (as nude model for both Ray and the reader, and as stripper for both Bumpers and the reader), she never relinquishes her subjectivity, insisting that while she may be the object in the eyes of the “other,” she nevertheless remains a “subject” to herself.

Increasingly, the notion that all individuals are both subjects and objects becomes thematized in Locas, not merely for Danita, but for others as well. Maggie, in particular, occupies a similar position, when, in Chester Square she is turned into an accidental prostitute. Stranded without money and without means of transportation, Maggie twice “sells herself” sexually, becoming an “object” in the capitalist economy, and tacitly rejecting her role as symbol of the classless Marxist/punk utopia.

If punk culture rejects the ways in which the dominant culture puts everything up “for sale,” then it undoubtedly rejects the notions that individual subjects can be seen simply as “objects.” Prostitution, on the other hand, is, in many ways, the ultimate symbol for capitalism. In prostitution, almost literally, “everything is for sale,” as it is in capitalist society more generally. Despite the logic of the prostitution=capitalism analogy, however, Jaime rejects the most extreme of its ramifications in “Chester Square.”

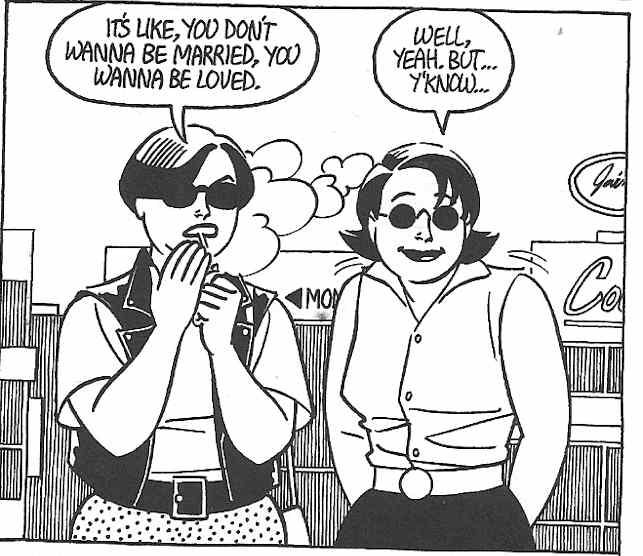

In the pair of panels pictured here, we see a clash of “Maggie as object” and “Maggie as subject.” In the first panel, she imagines herself as the prostitute she eventually (if momentarily) becomes, “posing” as a sex kitten who invites her own “use” by the men just outside the door. It’s clear though that this self-fetishization is simply a pose, or fantasy, when she is surprised by the knock at the door. Her humorously exaggerated response reveals other facets of her personality, beyond just as an object for sexual use. The juxtaposition of the two panels reveals two women juxtaposed, one of aggressive sexuality and the other of an exaggerated modesty. The fact that the two women are actually one at two different moments in time reveals a complex individual, who, when beyond closed doors, displays contradictory and complicated impulses.

Of course, Maggie is not, here, exactly “behind closed doors.” Rather, her naked body (like Danita’s) is on display for the reader, and in the first panel, she looks at us, inviting us to “use her” as we will sexually. The second panel, however, deflates the pornographic quality of the first, reminding us that behind every “objectified” woman is also a subject and behind every prostitute who is transformed into a commodity is a woman who may be embarrassed, humiliated, or even, simply, modest in her “real” life.

Maggie’s impulse toward subjectivity (again, like Danita’s) and her resistance to her own commodification, makes her reject the man, Enero, who in subsequent pages mistakes her for a prostitute, even though she was willing to sleep with him for free. Ironically, however, when she invites the security guard in for a sexual encounter that is not supposed to be a monetary transaction, he makes the same mistake, leaving her money on the nightstand. Though mortified, the money allows Maggie to escape the Square, taking a bus to her Aunt Vicki’s, where she eventually tells her friend Gina about the incident, noting that “I really didn’t feel bad about doing it. Like it was no big deal” (153). Though she eventually backtracks on this claim, calling herself a “whore…trollop, floozy, harlot, doxy, cocette, chippie” (153), it is clear that while Maggie (and the reader) might expect her commodification, or objectification, to rob her of her subjectivity, in fact, she leaves the encounter in much the same way that she entered into it, as a complex woman who is not defined by this single act. In fact, she only begins to see herself as a “whore” when she tells someone else about it, viewing herself not from the inside (as subject), but from the outside, through Gina’s eyes. Doing so allows Maggie to view herself as she initially views the prostitute, Ruby, who she is, for a time, mistaken for, not as a human being, but as a commodity.

The episode, then, like Danita’s posing and stripping, refuses a simple subject/object dichotomy, where there is an “original” subject of fantasy (the phallic mother), and a series of objects that replace her (fetishes). Instead, the replacements themselves are subjects, who may be objectified by society, or the individuals they interact with, but who cannot be reduced to such a function. Concomitantly, the book suggests that the ideals of acceptance of differences of race, gender, and sexual orientation are not proposed simply as symbols of a mythological or utopian punk past, but are instead cast forward as a goal for society that we must attempt to achieve in the present. When Maggie and Hopey reunite at the close of La Perla La Loca (or at the close of the original run of Love and Rockets), they do so only after they separate over issues of racial discrimination and homophobia. That is, if they are to move forward and reunite, they must overcome such differences, rather than “pretend they never happened” as fetishism (in Freud’s account) attempts to pretend that castration never occurred.

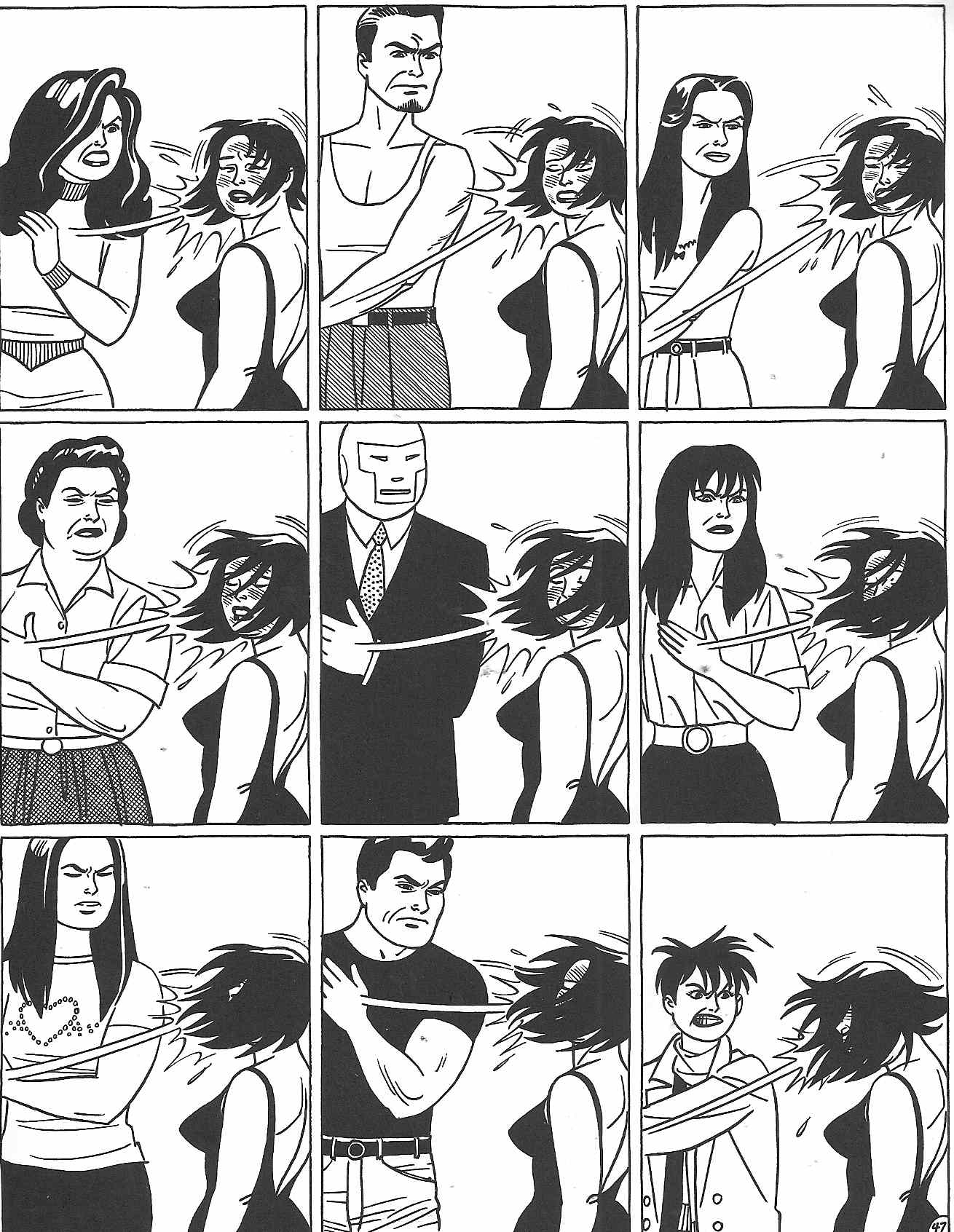

Again, this is explicitly emphasized in the closing pages of “Bob Richardson,” wherein Maggie has a dream/fantasy that Hopey never left her for the East Coast tour with her punk band which provides the impetus for much of the action of Wigwam Bam. Like the fantasy of the phallic mother, Maggie’s dream is a fantasy of wholeness and unity that predates all of the divisions that infect their relationship in the weeks, months, and years to come. Instead, however, Maggie “wakes up,” to be “slapped in the face” by all of the people she’s hurt in the interim (or whom she believes she has disappointed). She can only move forward, here, by rejecting her “dream” of a perfect past untainted by her own errors and those made by those around her.

The rejection of fetishism-as-nostalgia is articulated clearly at the close of Wigwam Bam, wherein Nan Tucker hires thugs to brutally beat both Crystal and Hopey as a warning to cover up the beating (and possible death) of one of the other fetishized play-acting “babies.” There, a fixation on a supposedly utopian “childhood” is explicitly coded as “dangerous,” resulting in a rude awakening to the realities of a world wherein self-interest trumps all. Though Nan and the sit-com mothers fantasize about a perfect union with their fetish “children,” in the end such a fantasy cannot stand up to naked self-interest, as they are willing to sacrifice (and brutalize) the fantasy to protect themselves. Wigwam Bam is not, however, the end of the story, and the brutality of exploitation and cover-up we see there (and also in Poison River) tell only part of Jaime’s story.

In the aftermath of the disillusionment of Wigwam Bam, Maggie, Hopey and their surrounding cast of characters consistently reject the notion that “living in the now” must simply mean the objectification and commodification of others, and the abandonment of a more utopian community which, it turns out, was always a fantasy to begin with. Instead, they search for a way to love and accept others’ subjectivities even after the corruption and commodification endemic to capitalist society. Even after Maggie is commodified as a prostitute, she moves forward in an attempt to make a better world for herself and her friends. Likewise, when Maggie is arrested at the close of “Bob Richardson,” Hopey abandons her self-interest in order to join her in the police car. Similarly, when Gina intuits her friend Xo’s need to win a wrestling match, she chooses to throw the match to her, despite the fact that she knows she will not get the reward for doing so that she wishes (159). Perhaps most tellingly, despite the abuse she has sustained at her hands, Maggie seeks out the regular Chester Square prostitute, Ruby, in order to make amends and to treat Ruby as a human being: a subject, not an object, despite her profession.

As Ruby herself articulates, then, the ultimate goal of the “love” of Love and Rockets is then a “love” of mutuality, openness, and intersubjectivity in the present, and in the real world, not a nostalgia for a utopian past that never existed in the first place. While there is certainly the notion in Locas that our present world is one of exploitation and objectification, there is also offered the possibility that even within that world, we need not see others merely as “means” for our own ends. When Hopey and Gina sacrifice themselves for the good of their friends, we are, perhaps, free to read those actions as self-interested, but it perhaps makes more sense to seem them as acts of love. Maggie’s variably successful efforts to make amends for her past behavior in the closing pages of “Bob Richardson,” both with Ruby and others, similarly indicates the importance of looking forward, not back.

Continually, then, as several of the other entries in the roundtable make clear, Jaime revisits the past in the ongoing Locas serial not to revisit a sentimentally idealized ür-time but to expose the ways in which the past was never like that. As in the Freudian account of fetishism, the phallic mother never existed, and so our attempts to return to her, or to an idealized past, are merely a series of self-deceptions. The recent storyline of Browntown, in particular, serves to remind us that the past is not a place free of exploitation, division, and oppression and is therefore not something to be nostalgic for, or to fetishize. Rather, as Jaime’s characters age inexorably along with us, we are reminded that if we want such a place to exist, we must work for it in the present, and hope for it in the future.

_____________

The Locas roundtable index is here.

_____________

More Works Cited

Hernandez, Jaime. La Perla La Loca. Seattle, Wa: Fantagraphics Books, 2007.

Marx, Karl and Friedrick Engels. “From The Communist Manifesto.” 1848, 1888. The Norton

Anthology of Theory and Criticism, Second Edition. Eds. Vincent Leitch, et. al. New York: W. W. Norton, Inc., 2001, 2010. 657-660.

This is a really great piece. It’s also sufficiently thought through and lengthy that comments seem superfluous…but what the hell.

As you say, it does seem in conversation with other discussions about nostalgia. You’re basically arguing that the nostalgia (and the fetish for nostalgia) are fully thematized and critiqued. You say:

“Jaime revisits the past in the ongoing Locas serial not to revisit a sentimentally idealized ür-time but to expose the ways in which the past was never like that.”

I certainly see where you’re coming from vis-a-vis Freud…but I’m not sure you really manage to engage with or put to rest the Lacanian argument I was making.

That is, for Freud the fetishization, or illusion, of the past is specifically the past’s wholeness, or the image of the past as a utopia. In Lacan, it’s not the past-as-utopia which is the false image, but the past-as-past. For Lacan, *everyone* is a phallic mother, in the sense that everyone is a comforting, falsely coherent image of themselves. The illusion, then, is not (or not just) the image of an idealized past, but the image of *any* past.

In this sense, Jaime’s insistence (in Browntown, for example) that the truth of the past is *not* utopia *but* exploitation is itself a reification of experience, of self, and (in this case) of Maggie. Maggie becomes *more* real, *more* an object of identification because of her vulnerability/flaws/lack of perfection.

For instance, in that sequence where she is sexy/cool and then cute/vulnerable/embarrassed, you read the second as a refutation of the first. But is it? Doesn’t the vulnerability, the knowledge of the *real* Maggie beneath the image, make the character *more* seductive, not less? If Linda Williams is right that pornography is as much (or more) about the fetish of knowing women as it is about the fetish of fucking them, then the vulnerability of Maggie, the sense that you’re seeing the *real* her, is as much of a fetish as the objectified male gaze — or even an extension of it.

Yeah…well, I would argue that one could use Lacan to make either point…but yes, Lacan does make the argument you’re making about “all of us” (that none of us are coherent, whole, explicable human beings…and any effort to make sense of ourselves as “selves” is a fantasy). The Real is, precisely, unrepresentable…and so any representation is an attempt to bring coherence and is thus a lie. Still, I think you could see the two Maggies, and/or the multiple Maggie “doubles” as Lacanian examples of the split self… showing that we are always and everywhere multiple and irreducible to a unity. Comics’ capacity to always being depicting multiple “images” of the same person is a good metaphor for this kind of Lacanian thought, I would say, and Jaime does thematize that by giving us “multiple Maggies”–even Maggies who are not Maggies…as Lacan would always say that we are not ourselves.

I think the idea of Maggie as fetish makes sense in the context of your other question…in that her “reality” can be both part of her idealization (that is, her complexity and “reality” is part of what we desire about her), but also part of the interruption of her idealization (part of her post-Oedipal status as entering the “real” world, or the Symbolic (which, for Lacan, of course, isn’t really real itself).

I haven’t read Linda Williams, so I can’t really comment fully on that…but I would say that there are a number of theoretical complications one could make (and by all means, go ahead), but this was really just an attempt to get on “paper” many of the things that came out through my teaching of Perla La Loca in the Fall… I know it may seem fully thought through–but from my point-of-view, it’s fairly half-baked (which is why I was happy to post it here—figuring if I ever try to “publish” it for real, it will be much more researched and theorized (for instance, I would probably re-read Marx on commodity fetishism instead of relying on my distant memory of that). I wrote it all in essentially a 7-8 hour span, so I’m sure there’s logical holes in it, and I’d be glad if someone were to point them out to me.

One thing I kind of wanted to get to (but ran out of gas) was trying to think this through in terms of a female reader. “Castration Anxiety” is obviously impossible to employ for such a reader…though I don’t think repression, replacement, etc. are. In that case, “fetishism” can’t exactly be about replacing the mother’s penis…and so you might end up in different places.

Oh…and I wouldn’t say one sees the “real” Maggie in panel 2…since Maggie is not a real person, obviously. I would just say that the text thematizes objectification vs. subjectivity there. I think it’s largely successful in doing so (in the context of the entire story–not necessarily just in those two panels), but one could certainly make the argument (as some of my students did), that the book largely objectifies women, even though it thematizes and explores the dangers of objectification.

“One thing I kind of wanted to get to (but ran out of gas) was trying to think this through in terms of a female reader. “Castration Anxiety” is obviously impossible to employ for such a reader”

You might check out Tania Modleski’s “Loving With a Vengeance,” about mass culture for women (Halequin novels, gothics, soap operas). She talks about the fact that Freud sees the uncanny as linked specifically to castration anxiety, and argues that this doesn’t make sense since women love gothic romance, which is all about the uncanny, *and*, like you say, women aren’t supposed to have castration anxiety. She says:

“suppose we view the threat of castration as part of a deeper fear — fear of never developing a sense of autonomy and separateness from the mother.”

From that perspective, she says, women’s fear would be greater, since they are constantly in danger of being seen as/forced into the position of their mothers.

Reading that, though, I actually think it makes sense to think of both men *and* women as suffering castration anxiety, which works fine if you think of the penis not as a literal penis but (as Lacan does) as the phallus — symbolic of power and authority. For women, particularly, the phallic mother could be seen as an image/possibility of equality or authority which is constantly denied by patriarchal society….

Whoops, have to stop! Mom and Dad just got here….

Well..Freud would go to the whole penis envy thing…which I think is largely a non-starter.

Anyway, it was I who recommended Modleski to you a long time back, ironically. I’ve only read parts of it, though.

It’s short! And very good; look in the index under castration anxiety and you’ll find the discussion I’m talking about.

Nothing really to say in re comments, just that I really enjoyed this post, Eric.

Well, thank you Derik.

Just a quibble- does Maggie really *accidentally* become a prostitute? Even if stranded with no money she still had freedom of action. It’s not like she woke up with the “john” right next to her in bed.

“but one could certainly make the argument (as some of my students did), that the book largely objectifies women, even though it thematizes and explores the dangers of objectification.”

Considering the ease with which she fell into hooking that conclusion is hard to escape.

My reading is that she slept with the guy, but not for money. He paid her because she mistook her for a prostitute–thus accidentally (this is the guy at Chester Square….she accidentally had an earlier experience at a bus station where she is mistaken for a prostitute and plays along…so, that one isn’t exactly accidental)

Pondering a proper response to all of this — but I found all of this provocative and compelling. At the very least, this is the level of thinking this material deserves … more later, with time to process my thoughts.

A pretty enjoyable essay (more satisfying than Part I for me), even if the Freudiam malarkey is such a massive farrago of utterly insane nonsense it feels like harnessing a fish to try an’ pull your carriage. ((“Phallic mothers”…please! The reductionistic simple-mindedness of Marx comes across like a reasonable breath of fresh air in comparison.)

Great analysis of the way Jaime explodes the way nostalgia idealizes the past, indeed (as with all the “replacements” enumerated) substituting a faux construct for a far less simple and satisfying reality.

Am reminded of Disney’s “Main Street USA,” where the kind of people who’d far rather flock to a Wal-Mart to do their shopping (and thereby kill off their actual “main streets”) happily swarm over and shop at a simulacrum of Norman Rockwell small-town Americana.

Come to think of it, also recall visiting Epcot many decades ago; it’s gotten more elaborate ( http://www.guide-to-disney.com/epcot/epcot.php ), but the same concept is at work.

But, isn’t this a commercialization of an all-too-human phenomenon, our tendency to stereotype, categorize people and places from a few clues? (A valuable trait, evolution-wise; if you see a raggedly-dressed, crazed-looking type striding toward you brandishing a knife, this mechanism speeds reactions, shouts “RUN AWAY!!!”)

Along this vein, there was a scene in a Jaime story where one girl, being introduced to the “punk” world, comes across a young guy with a mohawk, and comments how in “Mad Max”-type movies, guys like that are always portrayed as violent, menacing; but this chap’s really a softie…)

———————–

In the pair of panels pictured here, we see a clash of “Maggie as object” and “Maggie as subject.” In the first panel, she imagines herself as the prostitute she eventually (if momentarily) becomes, “posing” as a sex kitten who invites her own “use” by the men just outside the door. It’s clear though that this self-fetishization is simply a pose, or fantasy, when she is surprised by the knock at the door. Her humorously exaggerated response reveals other facets of her personality, beyond just as an object for sexual use. The juxtaposition of the two panels reveals two women juxtaposed, one of aggressive sexuality and the other of an exaggerated modesty. The fact that the two women are actually one at two different moments in time reveals a complex individual, who, when beyond closed doors, displays contradictory and complicated impulses.

———————–

But, the “Maggie acting like a blatantly seductive hooker” bit was just an act rather than a real part of herself. So it wasn’t “two women,” anymore than a six-year-old dressing up in a parent’s clothes becomes both a child and an adult.

She was trying out that persona; but her freaked-out reaction when reality intruded indicated that no, it wasn’t “in her” to be that…

———————–

My reading is that she slept with the guy, but not for money. He paid her because she mistook her for a prostitute…

————————

That’s exactly what happened. He was a sweet, kind of nerdish guy…

————————-

–thus accidentally (this is the guy at Chester Square….she accidentally had an earlier experience at a bus station where she is mistaken for a prostitute and plays along…so, that one isn’t exactly accidental)

————————–

If what you’re trying to say is she accidentally *became* a prostitute, I’d say, no she didn’t. She wasn’t “doing it” with that security guard in expectation of getting money; therefore his thinking she was one and leaving cash did not change her “sympathy fuck” into one motivated by the wish for monetary compensation.

—————————

Noah Berlatsky says:

…If Linda Williams is right that pornography is as much (or more) about the fetish of knowing women as it is about the fetish of fucking them, then the vulnerability of Maggie, the sense that you’re seeing the *real* her, is as much of a fetish as the objectified male gaze — or even an extension of it.

—————————-

Linda Williams, come join Freud in the “let’s not let reality get in the way of our theories” room!

Of course porn is not remotely about actually “knowing” women (never mind it being a “fetish”); these are utterly unrealistic, two-dimensional fantasies voraciously fucking and sucking.

Which is also why the Playboy “Playmates of the Month,” for all their erotic presentation, are not porn. There are biographies of them included, photos of them in their daily life, comments by them about subjects other than sex. Which actually shows a rather sweet interest by many males to see them as not mere pieces of screwable meat, but as persons…

Mike, Williams doesn’t think you *really* know women — whatever that would mean. But the fetish is the idea that you are eliciting real reactions from them; creating real pleasure; gaining intimate knowledge of who they really are, etc.

The point here for me is that Eric’s reading doesn’t actually contradict the critique that a lot of Jaime’s appeal/interest is in making authenticity claims. That is, he debunks the false nostalgic world to show you the real world of exploitation; he debunks Maggie’s sexy posturing to show you her real self. Even debunking punk rock to show you the truth of punk rock is a punk rock thing to do in a lot of ways.

This, more than any other piece in the recent (very good — please don’t misunderstand that) Locas roundtable really illuminated what I enjoyed about Locas and why. Great, great work.

—————————

Noah Berlatsky says:

…Williams doesn’t think you *really* know women — whatever that would mean. But the fetish is the idea that you are eliciting real reactions from them; creating real pleasure; gaining intimate knowledge of who they really are, etc.

—————————

I’d said, “porn is not remotely about actually ‘knowing’ women (never mind [that]being a ‘fetish’)”, and held off from the old citing the dictionary-definition bit. But alas, since everybody seems to be in the “words are whatever I feel like having them mean” mindset…

—————————

fetish

noun

1.

an object regarded with awe as being the embodiment or habitation of a potent spirit or as having magical potency.

2.

any object, idea, etc., eliciting unquestioning reverence, respect, or devotion: to make a fetish of high grades.

3.

Psychology . any object or nongenital part of the body that causes a habitual erotic response or fixation.

—————————–

Since we’re clearly dealing with something that supposedly causes an “erotic response or fixation” in this instance, and “the idea that you are eliciting real reactions from them; creating real pleasure” is not an “object or nongenital part of the body,” then that is not a fetish.

And sure, not only porn performers, but any hooker worth their salt knows to cater to the customer/consumer’s stimulating fantasy that they’re actually being pleasurably stimulating. (Getting things comics-related, in that dreary Chester Brown book one prostitute simply lays there inertly, and Chester thinks, “No tip for this one.” Ah, the glories of the “free market” in action!)

Not only is this not a fetish, it’s not even a rare phenomenon. When we crack a lame gag to our fellow office-workers, or tell a boring story about our kid, or engage in conversation, and they politely go “heh-heh” or feign interest, don’t we have the often self-deluding “idea that [we] are eliciting real reactions from them; creating real pleasure; gaining intimate knowledge of who they really are, etc.”? (And no, I don’t deceive myself for a moment that anyone’s minds are being remotely opened, much less changed, by anything I write here. I’m just doing this for my own satisfaction…)

———————————

The point here for me is that Eric’s reading doesn’t actually contradict the critique that a lot of Jaime’s appeal/interest is in making authenticity claims. That is, he debunks the false nostalgic world to show you the real world of exploitation; he debunks Maggie’s sexy posturing to show you her real self. Even debunking punk rock to show you the truth of punk rock is a punk rock thing to do in a lot of ways.

———————————

First, I really, really doubt that “a lot of Jaime’s appeal/interest is in making authenticity claims.” What the vast majority of his readers enjoy are factors hardly so rarefied: lively, vibrant characters going through a set of adventures and emotional/physical turmoil.

Sure, the “debunking” (especially when gathered together from a huge body of work; in the way that the statistically-minimal 1% of a billion makes quite an impressive heap) is part of his work. But how truly significant a theme is it?

The problem with peering at a messily sprawling body of work through thematic spectacles is that the “body” ends up getting the Procrustean Bed treatment: stretch it to fit, chop out the parts that don’t.

Eric’s reading is more generous than most along this vein. However, to make such a deal of what is only part of a substantial body of work, which gets taken to extremes with such attitudes as “a lot of Jaime’s appeal/interest is in making authenticity claims,” or, as Eric put it, “It is this model of replacing an absent original that is central to Jaime Hernandez’s work in general.” (Emphasis added.)

This throws off the appreciation of the actual work as it really is; creates a false, simplified simulacrum of it, that some will think, in self-satisfaction, tells them that they have “gain[ed] intimate knowledge” of what the work really is.

Checking I was spelling “Procrustean” right, I just ran across this bit…

————————————

Contemporary usage

A Procrustean bed/vibrating deck is an arbitrary standard to which exact conformity is forced. In Edgar Allan Poe’s The Purloined Letter, the private detective Dupin uses the metaphor of a Procrustean bed to describe the Parisian police’s overly rigid method of looking for clues. Jacques Derrida, in “The Purveyor of Truth,” his response to Jacques Lacan’s seminar on “The Purloined Letter” (1956), applies the metaphor to the structural analysis of texts: “By framing in this violent way, by cutting the narrated figure itself from a fourth side in order to see only triangles, one evades perhaps a certain complication.” This is one of deconstruction’s central critiques of structural (and formal) literary analysis.

————————————-

Why, how sensible and perceptive! I takes my hat off to you, Derrida…

————————————-

…A Procrustean solution is the undesirable practice of tailoring data to fit its container or some other preconceived structure. A common example from the business world is embodied in the notion that no résumé should exceed one page in length.

In a Procrustean solution in statistics, instead of finding the best fit line to a scatter plot of data, one first chooses the line one wants, then selects only the data that fits it, disregarding data that does not, so to “prove” some idea. It is a form of rhetorical deception made to forward one set of interests at the expense of others. The unique goal of the Procrustean solution is not win-win, but rather that Procrustes wins and the other loses. In this case, the defeat of the opponent justifies the deceptive means.

————————————

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Procrustes

This psychic satisfaction of “I and my small, exclusive group understand the way the world/a work of art really is, unlike all the other easily-deluded cattle” ranges from ideologues (Marx & those 80’s yuppies agree: “the bottom line of everything is money!”), to religious True Believers, to conspiracy theorists.

Re that last group, speaking of Marx:

——————————–

Bruno Latour suggests that the widespread popularity of conspiracy theories in mass culture may be due, in part, to the pervasive presence of Marxist-inspired critical theory and similar ideas in academia since the 1970s.

Latour suggests that about 90% of contemporary social criticism in academia displays one of two approaches which he terms “the fact position and the fairy position.” The fact position is anti-fetishist, arguing that “objects of belief” (e.g., religion, arts) are merely concepts onto which power is projected; the “fairy position” argues that individuals are dominated, often covertly and without their awareness, by external forces (e.g., economics, gender). “Do you see now why it feels so good to be a critical mind?” asks Latour: no matter which position you take, “You’re always right!”

Latour notes that such social criticism has been appropriated by those he describes as conspiracy theorists, including global warming skeptics and the 9/11 Truth movement: “Maybe I am taking conspiracy theories too seriously, but I am worried to detect, in those mad mixtures of knee-jerk disbelief, punctilious demands for proofs, and free use of powerful explanation from the social neverland, many of the weapons of social critique.”

———————————

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conspiracy_theory#Psychological_origins mentions how

———————————–

Eric Berlatsky says:

Again, there is no reason why we must believe in the narratives Freud provides, but it does provide a useful heuristic for understanding Jaime Hernandez’s work as well and especially the stories collected in La Perla La Loca…Perhaps most central and helpful in looking at these stories is the central truth of these Freudian narratives, which is that “nostalgia” here is never nostalgia for something real, but is instead nostalgia for a fantasy of wholeness which never existed.

————————————-

(That “central” word keeps cropping up!) And, why should the reasonable and hardly original perception that “…’nostalgia’ here is never nostalgia for something real” be linked to that massive heap of Freudian B.S.?

To choose something so ludicrous that it makes “a cabal of rich Jews runs the world” seem like hard science in comparison as “a useful heuristic for understanding Jaime Hernandez’s work,” whose nonsensical terms, concepts and inventions keep getting invoked again and again, even if to then be dismissed (“…this is simply an Oedipal fantasy that serves to structure the boy’s psyche, but has no basis in reality.”), is a rather self-defeating approach.

Mike–without engaging with all of your concerns and complaints….I’ll briefly address 2…

1) The notion that nostalgia is never nostalgia for something real. It seems to me that sometimes nostalgia IS nostalgia for something “real” (one’s childhood or hometown or whatever), but it is looked at through “rose-colored” classes, or whatever, which makes it seem better than it was. In the case of the phallic mother, it’s nostalgia for something that never existed, but which the child, even at the time, imagined did.

2) Your claim that we could understand all of this stuff without recourse to Freudianism at all may be somewhat the case…but in both bros. Hernandez (more so in Gilbert, perhaps, but in both, I would argue), there’s an open courting of Freudian theory. So…the claim is less that the bros are expressing their own repressed desires for phallic motherhood, etc, but that they are using Freudian ideas intentionally to explore/express a variety of things (discussed in the essays). In Gilbert, I find it hard to avoid that he’s intentionally engaging not only with the Oedipus complex, but with phallic mothers, fetishism, and the whole kit and caboodle of Freudian theory. I don’t think the pre-op transsexual strip joint is some kind of weird coincidence and that I am somehow bring phallic motherhood to the text. I think the text itself (or GIlbert if you prefer) openly exploits and explores the idea. The link to Jaime is somewhat less overt, but we’ve still got fetishes (sit-com moms), Marcia/Marco, a chain of substitutions/replacements, etc. So…my point was more, you don’t have to “believe” Freud to be “right” about human psychology to see it as useful for looking at these texts. While not “true” in reality, perhaps, Freud’s ideas are largely true here, because the creators deploy Freud’s ideas. In Gilbert, I don’t see how you can argue against that, to be honest, which is why I started there—but once you see the connections to Jaime’s work, it’s there too.

I’d agree that Gilbert is consciously thinking about Freud…and I think Jaime too, though for Jaime it may well be thinking-about-Gilbert-thinking-about-Freud.

I also would argue though that Freud is just a really provocative thinker. His claims to be doing science are obviously ridiculous, and he’s a big old crank…but as a storyteller and creator of fictions, he’s pretty amazingly talented and often profound (moreso than Gilbert or Jaime, to my mind.)

Or to put it another way…the vast majority of comics aren’t scientifically true either, and many of them (Watchmen, Wonder Woman) were created by big old cranks. That doesn’t mean that reading them and thinking about them is worthless, or that they can’t tell us something about existence, or people, or ourselves.

Does it really matter if the myth one uses to intermediate the emotional phenomenon of longing for a idyllic past one did not actually experience is the phallic mother or the Garden of Eden (which slipped into Eric’s piece here with the word “prelapsarian”) or the Good Old Days when Saturn ruled, or before Pandora’s Box was opened?

None is science; all are useful. If Jamie is parsing this through the Freudian myth structure — and the transsexual is at least a nod in that direction, then it’s probably worth considering his work in Freudian terms even if (or “even though”) Freudianism is crap.

Great responses, guys! (Uh, are my accidental “runaway italics” infectious?)

Never heard any of the Hernandezes cite Freudianism as an inspiration, though his nonsense has certainly pervaded the culture sufficiently so it could’ve been an “unconscious influence.”

Google’ing to see if anything turns up here…

A spiffy piece at The Comics Grid (which I’d never heard of ’til it was recognized as a source of fine comics critism at HU):

————————–

In Jaime Hernandez’s Ghost of Hoppers Chicana punk Maggie Chascarillo returns briefly to the Southern California town of her youth, Huerta (the “Hoppers” of the title). Momentarily distracted, she loses her way in the streets where she grew up, and even appears threatened by a mysterious figure. The experience is disorienting and disturbing, and has an uncanny quality….

Sigmund Freud popularised the trope of the uncanny (via Ernst Jentsch), illustrating the concept by recounting an anecdote about getting lost in a provincial Italian town and always, inadvertently, returning to the brothel quarter (Freud, 359). …The phenomenon of unintended recurrence provoking a sensation of helplessness and uncanniness (Unheimlich) is achieved via the interpenetration of the familiar with the strange, and the non-recognition of that which is hidden and brought to light. Although Maggie is in an environment that ought to be familiar, the result is much the same; the feeling of discomfort and disorientation emphasised by the visual shifts in scale and perspective…

————————–

http://www.comicsgrid.com/2011/07/gothic-hernandez-hoppers/

A segment of “Freud’s Mexico: Into the Wilds of Psychoanalysis” By Rubén Gallo at http://tinyurl.com/d9oav7s has some fascinating stuff about the Freud/Mexico/assassination of Trotsky connection. Pg 221 mentioning how the assassin of Trotsky (the revolutionary having an affair with Frida Kahlo, an icon of Los Bros) was exposed by a Mexican criminologist with an “interest in both psychoanalysis and the Trotsky case”; the murderer named, um, Jaime Ramón Mercader del Rio Hernandez…

Holy synchronicities, Batman! No wonder I’m more of a Jungian than a Freudian…

John– Thanks for the kind words!

Mike– The Uncanny (like so much else in Freud) actually rests on castration anxiety and all it entails as well.

Hevvins; is everything in Freudianism penis-centered?

Did this guy ever interview quantities of children to discover their possession of the Oedipus Complex and castration anxiety, or confirm his theories, or did he just make it up out of his head and expect everybody else to take it on faith?

Am reminded of…

———————————

Aristotle maintained that women have fewer teeth than men; although he was twice married, it never occurred to him to verify this statement by examining his wives’ mouths.

— Bertrand Russell

———————————-

In Aristotle’s favor, his “A likely impossibility is always preferable to an unconvincing possibility” is a painfully astute commentary on the limitations of human “reasoning.” ( From http://www.todayinsci.com/A/Aristotle/Aristotle-Quotations.htm )

———————————–

Noah Berlatsky says:

…For instance, in that sequence where she is sexy/cool and then cute/vulnerable/embarrassed, you read the second as a refutation of the first. But is it? Doesn’t the vulnerability, the knowledge of the *real* Maggie beneath the image, make the character *more* seductive, not less?

——————————-

To some of us, yes. Hardly a widespread male reaction, though; in Daniel Clowes’ great “Ugly Girls,” in singing the praises of unconventionally-beautiful women, he bemoans the popularity of inhuman, plasticized “beauty”: http://singleape.com/stuff/ug.html .

…An ideal which this touchingly vulnerable girl sadly wishes to attain, like Henri Rousseau wishing he could paint like Bouguereau: http://0.tqn.com/d/arthistory/1/0/u/1/1/Norman-Rockwell-Girl-at-Mirror-1954.jpg

“Hardly a widespread male reaction, though”

More widespread than you’re giving it credit for, I think; Jaime sells pretty well.

“Hevvins; is everything in Freudianism penis-centered?”

Pretty much.

Mike,

Interviewing children wouldn’t help matters. The whole point is that this stuff is repressed (and thus unfalsifiable). Freud did do clinical work…but he also seems to have made lots of stuff up.

I just read Freud’s first article about hysteria and child sexual abuse, in which he argues (quite compellingly) that the symptoms he was seeing as a clinician were caused by his patients having been abused as children.

Of course, he later took it all back and said the patients were just imagining the abuse because he didn’t want to believe that fathers actually did that sort of thing….