Reprinted from The Comics Journal #250 (2003)

“But have you heard anyone say, “Lord! When I was young, we didn’t have such nice games to play!” Or, “When I was little, there weren’t such wonderful story books!” No. Whatever people read or played with in their childhood not only seems in memory to have been the most beautiful and best thing possible; it often, wrongly, seems unique.”

“Children’s Literature”, Walter Benjamin

In 1956, on the imminent demise of EC Comics, Larry Stark, one of the company’s most ebullient young fans wrote a heartfelt elegy for the “best-written comic magazine line ever published” (Hoohah! #6). Amidst enthusiastic descriptions of the EC office and its working practices, Stark managed to provide a fan’s eye analysis of the comics themselves. “At their best,” he wrote, “EC was easily on par with the best pulp fiction available. And, if specific individual stories were considered, many of them were a good deal better, both in originality and concept and completion of expression….If any popular writing deserves a claim as literature, this does also. They were, at their best, mature conceptions totally explored, and with a constant attitude toward realism and honesty mixed in with the short, sharp crackle of drama.” What we can detect on cold hindsight is a young reader’s devotion, mixed with an instinctive understanding that the comics he was reading were still lodged in the ghetto of world art.

A few decades later, the EC line occupies no less than 4 spaces in The Comics Journal’s Top 100 comics of the century list, a ranking exercise which should put paid to any claims that this magazine has an elitist stance. The question for today’s readers is why a line consisting of “the best pulp fiction” and sometimes “a good deal better” is still considered among the best comics ever made.

Some of the answers to this question are quite apparent, among them a blindness and mule-headedness born of nostalgia. These are rose tinted lenses that have adhered so tightly to the eyes of most comics critics that they cannot be eradicated without immense difficulty. Suffice to say, the judgements made by critics and readers in assessing their favorite art form are firmly entrenched in their childhoods.

But first, a possible exception.

Mad #1-20

It is only in the case of Mad that EC manages to justify a degree of its reputation.

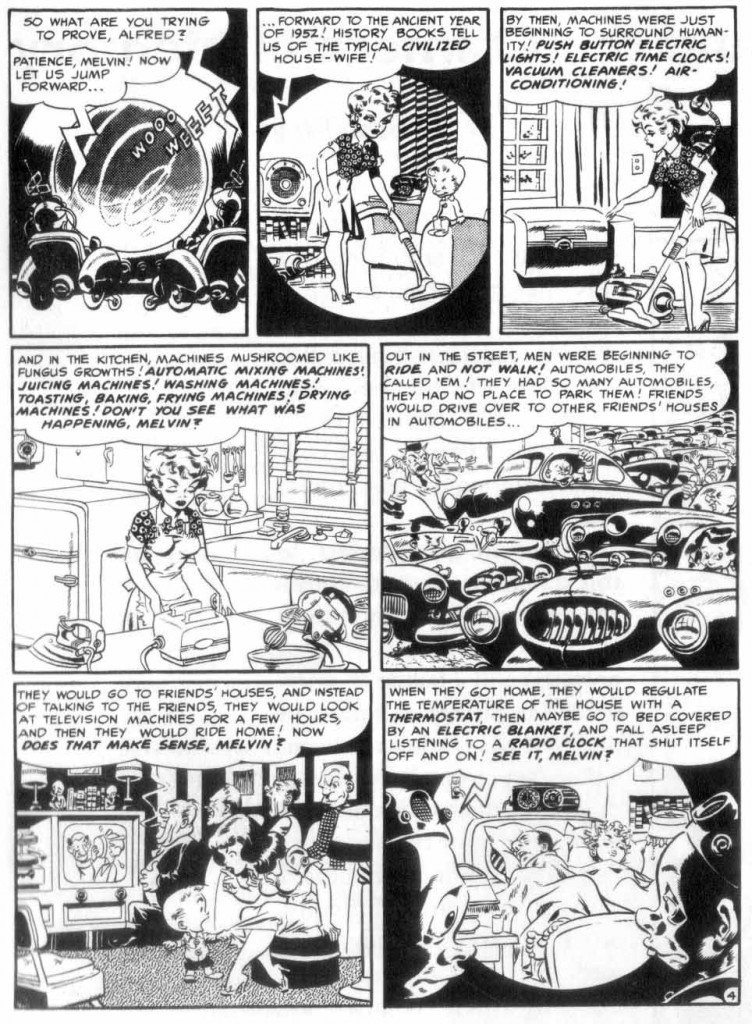

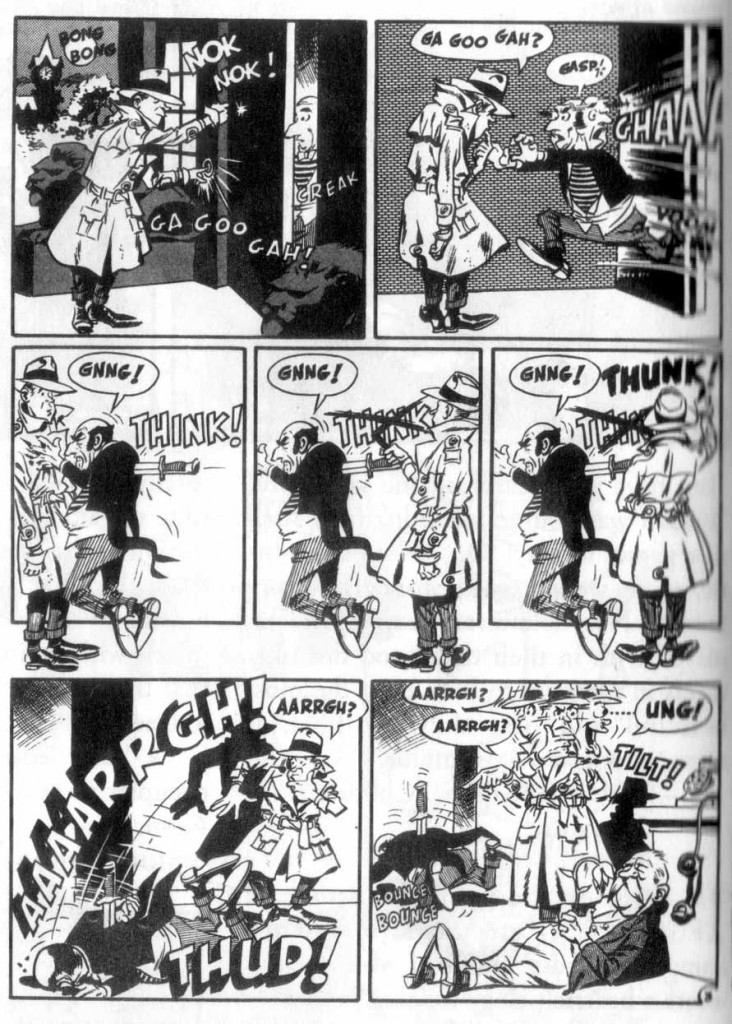

Enough has been written about the merits of these issues that I will not bother dwelling at length on them. Starting somewhat bumpily with plots which read like standard non-humorous EC texts (only with “funny” drawings) before proceeding to parodies of television shows, classic strips, and various DC and pulp heroes, these early stories were adorned with endless visual treats, immaculate artistry, a number of classic Hey Look! reprints and a set of outstanding covers and cover concepts. Kurtzman was undeniably a master of the form and the influence of Mad on American and European artists is inestimable. The strongest legacy of Mad would appear to be a certain subversivness and visual invention. In his introduction to Harvey Kurtzman’s Strange Adventures, Art Spigelman virtually admits that we wouldn’t have Raw magazine as we now know it without the influence of Kurtzman’s Mad. Writing in this magazine, R. C. Harvey insists that “almost all American satire today follows a formula that Harvey Kurtzman thought up”, a statement which I would not care to dispute.

Such influences may suggest a certain level of quality inherent in the series but cannot be the sole basis upon which the greatness of Mad is built. Objectively speaking, there is a lack of timelessness, consistency and universality in these early issues.

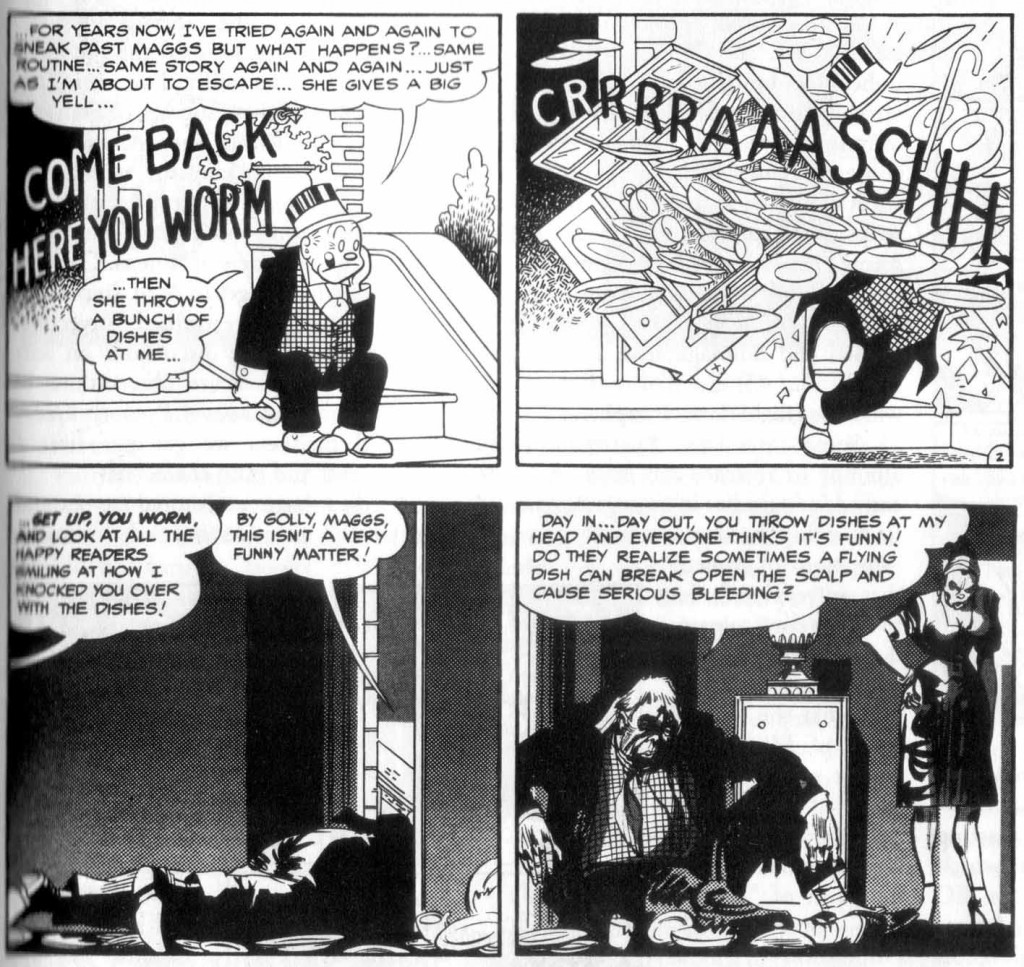

For every “Flob was a Slob”, “Superduperman”, “Little Orphan Melvin!” and “Bring Back Father!” (a Kurtzman and Krigstein masterpiece) there’s something wordy and dismal like “Black and Blue Hawks” (which is still undoubtedly loved and appreciated by some) and “Smilin’ Melvin!”.

Outside a Western context (one which is immersed in the substantial back catalogue of classic strips, pop artifacts and comics), Mad seems almost irrelevant, incomprehensible and dull. Would anyone consider “Blobs!” (Mad #1) or something as cliched and unimaginative as “Dragged Net!” (Mad #3) essential reading (because that’s what the label classic implies)?

Some years later, Kurtzman would attempt to recreate the magic of these early Mad parodies in Strange Adventures. In so doing, he demonstrated the severe limitations of comedy restricted (for the most part) to parodies of genres or existing works of art (for this is what the first twenty issues of Mad largely consist of). Nearly ten issues of Mad go by before formula gives way to innovation in the form of “Murder the Story”, “3-Dimension” and “Book/Movie” culminating in the issue 20 story, “Sound Effects”. These are stories which do not receive the acclaim or nostalgic turns of the parodies but were important in adding a certain potency and variety to the mix being accomplished pieces of proactive humor, an area which is inherently more difficult to explore.

Yet, through these early issues (and for a considerable length of time following), the writers and artists of Mad consistently failed to divorce themselves from their roots in parody and second hand satire, the unwavering elements that had endeared the series to a legion of readers. EC fans hardly ever mention these early pieces of proactive humor and I suspect that part of the reason is that children prefer the more straightforward humor of the parodies and find a certain comfort in humor directed at familiar targets such as Superman and Tarzan. The adults that have developed from these roots consistently fail to extricate themselves from this position.

As a kind of bible of pure comedy, the early Mad falls remarkably short of perfection however influential. Where is the personal slander, the rambunctious sex, the mad philandering, the sublime depravity and the political skewering we expect of the richest sources of comedy? Over two millennia ago, Aristophanes was brilliantly mocking the tragedies of Euripides (Women at the Thesmophoria) and risking prosecution with forthright attacks on the leaders of Athens. Contrast this with what we get in Mad. In place of Aristophanes’ unrestrained invective, Shakespeare’s poetic discursions on self-delusion, Wilde’s acute observations of social norms, and Monty Python’s Dada flavored madness we get parodies of superheroes and pulp characters.

Critics have attempted to extend Kurtzman’s parodies beyond witticisms concerning the immediate pop culture products they lampoon, suggesting rather a primary preoccupation with societal ills but this is plainly ludicrous when one looks closely at acknowledged “classics” like the second “Melvin of the Apes” story or “Ping Pong”. It is certainly true that Kurtzman managed to achieve many of these ends over the course of his long career but the early issues of Mad—the ones which have attracted the most reverence—represent something cropped and stilted, not so much unworthy as failing to exploit the full measure of the history of comedy.

Further, one wonders if the consistent elevation and reverence of Mad asserts a more insidious influence on American funny books. Within America (and this excludes a whole slew of modern and classic foreign titles) there is an extraordinary paucity of long form works of comedy. Decades of imitation and decay have left us with a small clutch of longer works including Feiffer’s Munro and Tantrum, Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary, Hate and the debatable merits of Epicurus and Why I Hate Saturn. There is little doubt that such developments are largely a function of the nature of the American market and its economic realities—namely its dependence on short form works until a few decades ago—but one wonders if it is symptomatic of a paucity of ambition and discipline among creators of comedy.

The prevailing culture of comedy in comics has somehow managed to convince artists in the field that where humor is concerned, brevity is the only form that they need consider. They have no finer ambitions than being gag men. What was once a dictate of business and the economy has now become the creative norm. The flurry of third rate parodies which were released during the black-and-white explosion of the late 80s and early 90s were the nadir of this tradition, the product of artists who failed to see the inherent limitations of this form of expression and who refused to broaden their horizons. It was an almost inevitable end point for a form so tied to its merely acceptable roots. The classic issues of Mad were an important step in the refinement and articulation of a language. They should not be considered or treated as if they were the final flowering of a genre.

The EC Horror Comics

“Oh I think you’ll find the further back you go the better they were. But simple; they weren’t classy. They weren’t great literature, but they were good. Like horrible…Yeah, they were all right. If you start judging them as works of art, you’ll never get anywhere. Judge by the fact that they were comics books written for fourteen-year old kids, sixteen maybe – we never thought we were hitting any higher than that in the beginning – who just like a good scary story to make it rough for them to go to sleep.”

Al Feldstein, from an interview in Tales of Terror

There are certain comics and stories that form the solid bedrock upon which the reputation of the EC line has been based. One of the least creditable of these foundations has to be the comics of the three major EC horror lines.

The EC horror titles as a whole have failed to generate any intelligent discussion or analysis apart from their relationship to American pop culture, the Kefauver hearings, and Seduction of the Innocent. In short, most appreciations of the EC horror line are largely bereft of genuine aesthetic considerations often boiling down to pronouncements that they were fun, influential, irreverent, and exciting for children.

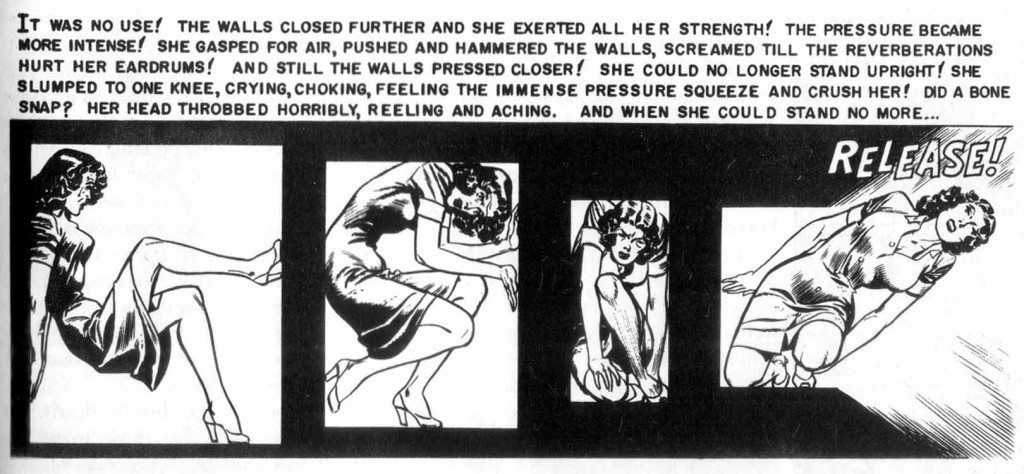

I am not suggesting that children should be deprived of profane fantasy but the finest children literature (and this is what is being claimed for EC) does not permit such concerns to overwhelm a certain truthfulness and sophistication. However much we admire the black humor of these stories, there should be more to a good children’s comic then unabashed glee at decapitated body parts roasting on a barbecue, choppers sliding into human heads, fermenting appendages, and zombies feeding on human flesh.

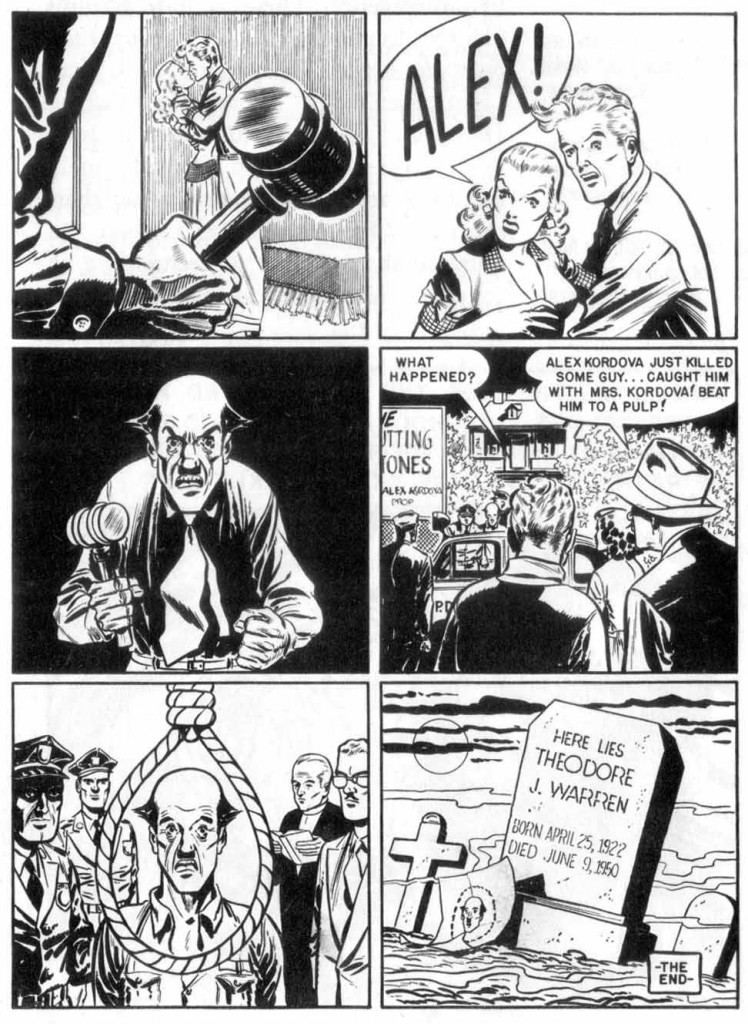

The primary emotions and personalities of the characters within the horror titles almost never (aside from the occasional doting wife who gets impregnated by her dead husband) extend beyond the limited values of hate, lust, covetousness, and fear. The recycled plot ideas provide the same sense of security children today feel when they watch episodes of Pokemon: the fetish (voodoo dolls, statues, and paintings) device; the lover’s return from the dead; the buried alive motif; the horrible unmasking shock ending—all of these and more are looked upon with affection and charity rather than with disdain and boredom. More platitudes can be found in the infamous retribution endings which the EC writers were unable to extricate themselves from even in the context of the early issues of Mad: don’t mess with witchcraft or you’ll be buried alive or catch leprosy; please don’t murder or you’ll be consumed by a zombie and do not covet thy neighbor’s spouse or you’ll be electroplated, decapitated, or buried alive. All of which, I’m sure, are fine upstanding lessons for a child but hardly the stuff of greatness.

There are examples of stories that are possessed of some narrative and sequential intelligence. These include Johnny Craig’s “Impending Doom” from Tales from the Crypt , “Whirlpool” and “Star Light, Star Bright” from The Vault of Horror and Gaines, Feldstein and Davis on “Let the Punishment Fit the Crime”. But these are the exceptions rather than the rule. One must wonder where we lie in the aesthetic understanding of comics if we must continue to admire stories because they are campy and merely well drawn. Shouldn’t such childhood experiences be confined to an aesthetic boothill alongside like-minded, nostalgia-laden refuse like The Twilight Zone and The Outer Limits? Why not rather rest our sights on stories that are well written and possessed of mature insights that are communicated with delight and horror to their young readers?

In Tom Devlin’s abandoned essay concerning the legacy of EC (TCJ #238), the benefits of a more cartoony style were touted as a superior form of expression in comparison to the tendency towards realistically drawn art in the EC line. This is a false dichotomy which restricts the merits and qualities of “realism” to a handful of mediocre comics. One could cite a number of realistic (and I use this term purely in its comic book parlance) artists and series whose merits far exceed those of a whole generation of “cartoony” modern American artists: Alberto Breccia, Dave McKean on Cages, Schuiten and Peeters on the Les Cites Obscures series, Moebius’ Airtight Garage, Taniguchi on The Man Who Walks and Sakaguchi on Ikkyu.

If there are indeed any trends which EC encouraged these would be an over-reliance on illustration over the narrative powers of comics and the cultivation of a critical inability to look beyond that which is simply well executed. The EC line has fostered, encouraged and deceived a legion of artists (as well as readers and critics) who remain content with finding a safe and commercial style upon which to earn a living and who do not find any value in discovering new avenues for their craft or intellects.

Even so, the EC line is clearly not solely responsible for these prevailing trends and attitudes. They may be seen merely as the symptoms of an insidious cancer or virus; constrained irreparably by commerce and reinforcing beliefs by their firm entrenchment in the popular tradition of comics. Their continued reverence suggests how little ground we have gained in the intervening years.

EC’s Science Fiction Line

“The EC approach in all these books is to offer better stories than can be found in other comics. At EC the copy itself – both caption and dialogue – has taken the number one position. This is a switch from the old days of comics when the art was most important and the story secondary. We take our stories very seriously. They are true-to-life adult stories ending in a surprise.”

Wiliam M. Gaines, Writer’s Digest

The EC science fiction collections, (most notably Weird Science, Weird Fantasy, and Weird Science-Fantasy) present smaller pillars in the edifice that we are discussing. Not surprisingly, the arguments for the qualities of the EC Science Fiction line are largely similar to those extended for the horror comics.

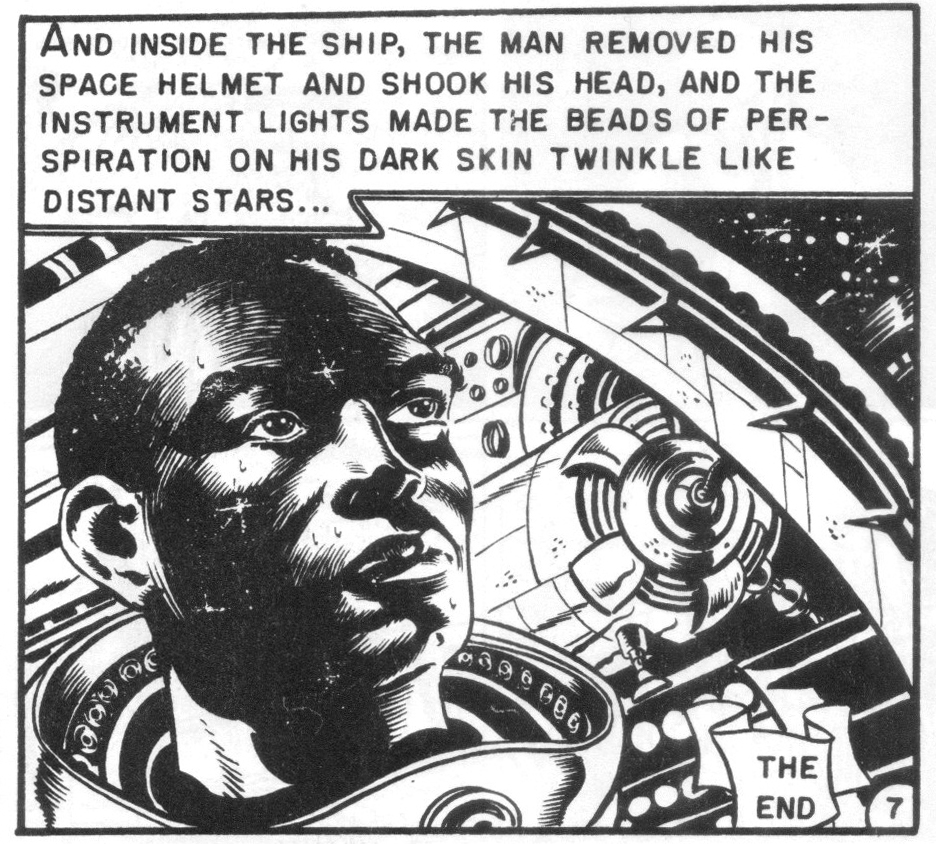

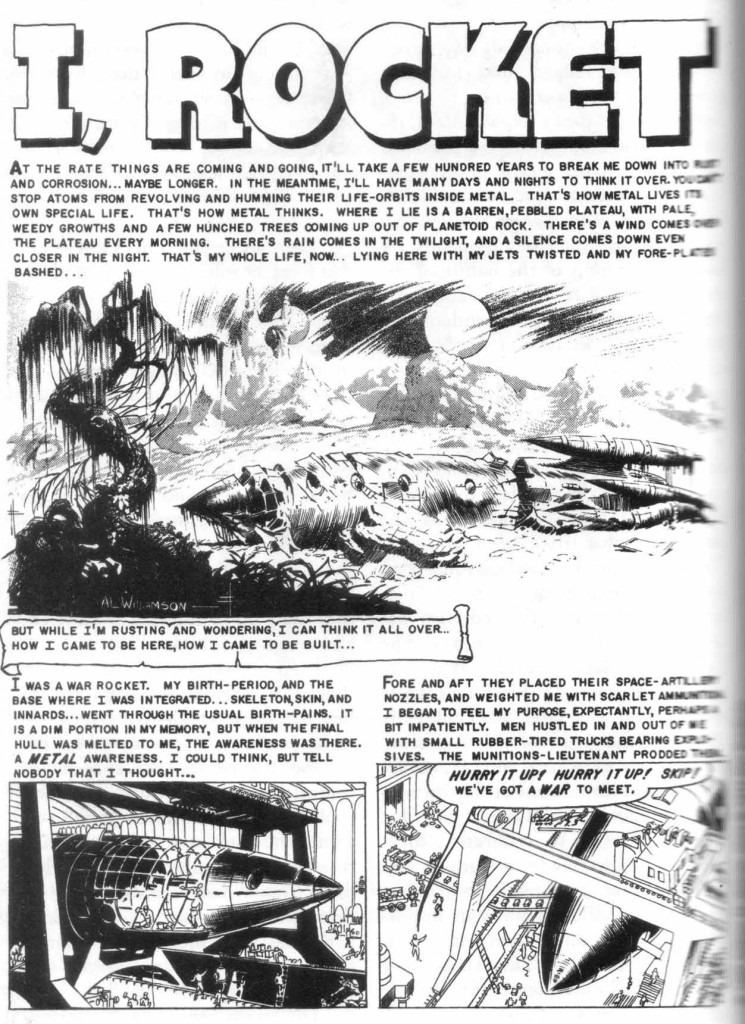

I will spare readers of this essay any detailed rants concerning the extended sermonizing of “classics” like “Judgement Day” or the regurgitated nonsense of “He Walked Among Us”. Suffice to say that the most coherent and imaginative of the EC science fiction comics were the Ray Bradbury adaptations; stories such as “I, Rocket”, “The Million Year Picnic”, “There Will Come Soft Rains” or “The Flying Machine”. Yet these retellings do not bring us fresh perspectives or revelations and exist as insignificant appendages to the original stories.

An inexcusable proportion of these adaptations amount to illustrations of text with a scattering of dialogue balloons, a manifestation of the way EC’s stable of writer’s and artist’s worked on their stories during their short deadlines. In so doing, they provide further credence to the belief that comics are indistinct from illustrated prose, a position which is no longer tenable aesthetically in the light of modern day advances in graphic storytelling.

In the 1950s, Bradbury was writing alongside the likes of Robert Heinlein, Arthur C.Clarke, Fritz Leiber, Brian Aldiss, and Alfred Bester. Later years would bring us the classic works of Philip K. Dick, Harlan Ellison, John Brunner, Ursula K. Le Guin, J. G. Ballard, Roger Zelazny, and Gene Wolfe. Beginning with their imaginations and ideas, these writers charted a path through literary science fiction into acute considerations of the artistic aspects of their chosen genre.

Science fiction in American comics, on the other hand, is dead. Quite frankly, there is little we should expect from a genre where a handful of weak fantasies created in the 1950s are still seen as the bench mark for all future works. Rather than advancing with the literary giants in the field, comics writers and artists have been crippled by the conservative and unenlightened trends so prevalent till this day in science fiction art and illustration. These are the very values which EC fans continue to cling to when they focus solely on the flamboyant artistry of Frazetta, Orlando, Williamson, and Wood to the exclusion of all else. We should be filled with pity not despair at their ignorance.

Crime and Shock SuspenStories

The one clear distinguishing mark of the SuspenStories lines were the tales of social conscience (the so-called “preachies”). Apart from these, both these series were largely indistinguishable from the EC horror and science fiction lines with their mishmash of stories of retribution, “suspense”, and “shock”. EC fan and historian, Digby Diehl, even deigns to suggest that Shock SuspenStories tended to offer up “a Whitman’s Sampler approach—often combining a crime story, a science fiction story, a horror story, and a shock story in the same issue” (Tales from the Crypt – The Official Archives). It is a comment that betrays the lack of ideological deviation in these comics compared to the other more focused New Trend comics. There is little doubt that the “preachies” lodged within the pages of the SuspenStories titles (in particular Shock SuspenStories) were daring, controversial moves at the time. Yet mere artistic courage cannot be the final arbiter in decisions concerning the absolute worth of a piece of art.

There is something dreadfully hollow beneath the noble veneer of these stories. The “preachies” were hopelessly didactic, simplistic, and inarticulate; failing at every point to delineate character or elicit sympathy for their cause. It is also notable that the same writers and artists who willingly allowed a considerably more lurid form of violence to pervade their horror and crime fantasies, patently failed to use these tools in a more truthful yet forceful manner when it came to depicting those stories grounded in “social realism”. Worse, this was “social realism” riddled with “white” lies.

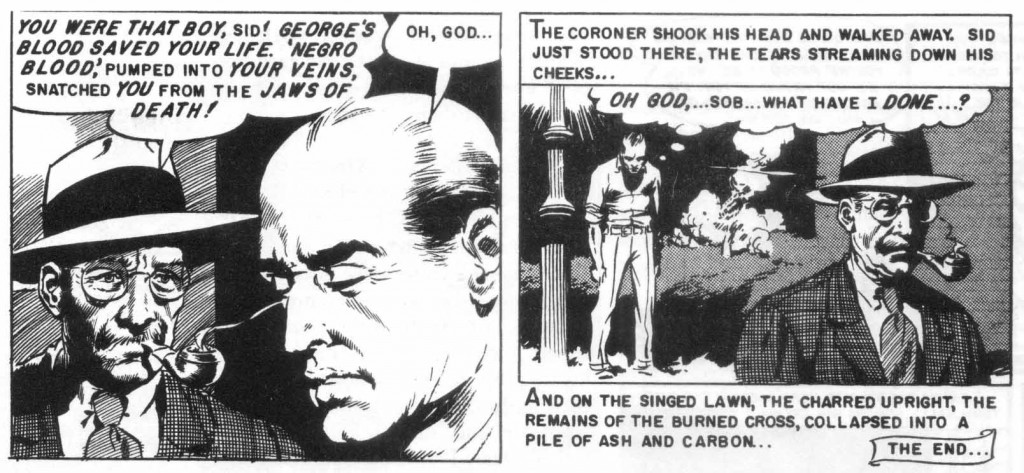

“The Guilty”, a story about injustice towards blacks in which an innocent black man is methodically murdered while in custody, rids itself of any sense of credibility with self-righteous, non-introspective editorial comment: “But for any American to have so little regard for the life and rights of any other American is a debasement of the principles of the Constitution upon which our country is founded.” The story “Blood-Brother” has a cross burning racist breaking down in tears of repentance when he discovers that he was once saved by some “negro blood” as a child—a somewhat implausible if not quite laughable sentiment in a country that was once more used to extracting every last pound of flesh from their black slaves. Pollyanna would probably approve.

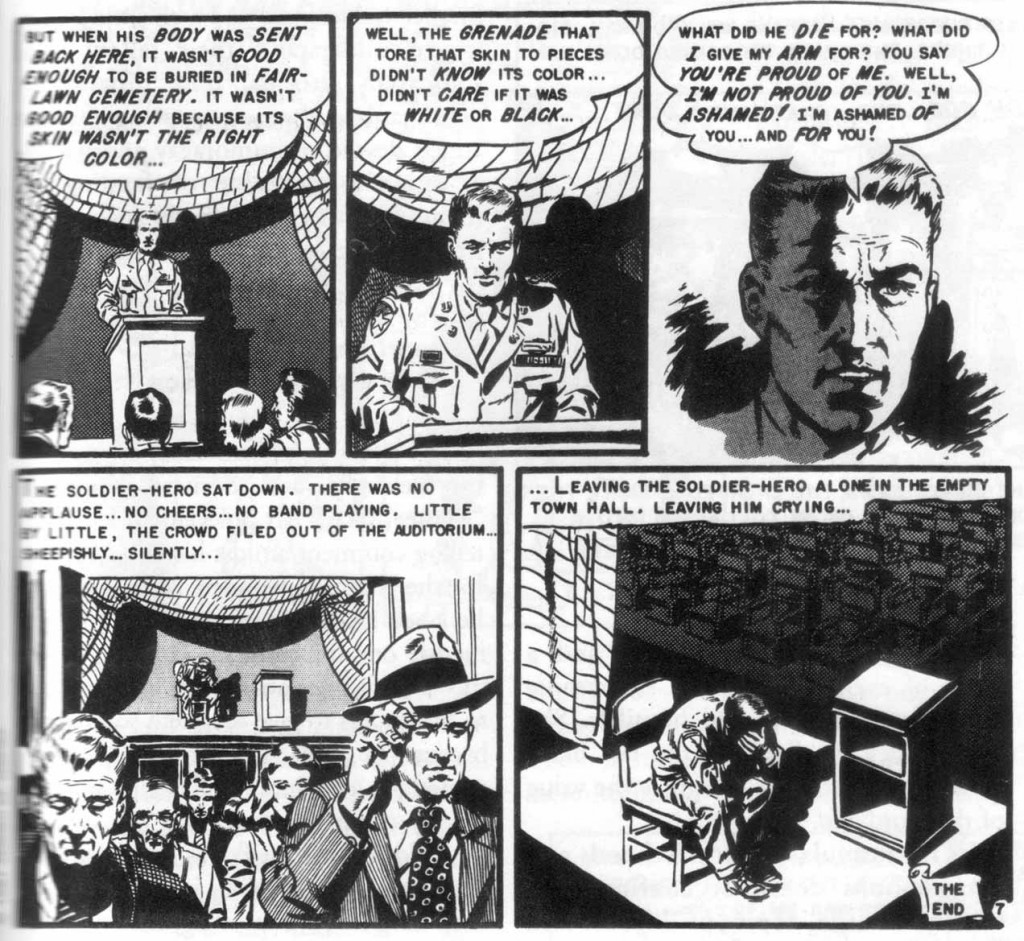

The typical EC African American is a silent, passive individual; an innocent without voice or passion in the face of society’s racism. There are very few exceptions to this. The black solider of “In Gratitude” is, admittedly, said to be brave, but is unfortunately quite dead. He is refused a burial plot on “white” land and his fellow white solider pleads on his behalf.

The authoritarian position of the black astronaut in “Judgment Day” (from Weird Fantasy #18) is little relief from this debased pattern. In the cloistered nunnery that is the EC SuspenStories line, the black man is dignified but not proactive; a sympathetic martyr not an angry, forceful activists. Yet a few years after these stories were published, Rosa Parks would step on a segregated bus triggering off the Montgomery bus riots and a series of events that would undermine and refute these lies and homilies. She was neither the first nor the last black person in America to recognize the value of the word “no.”

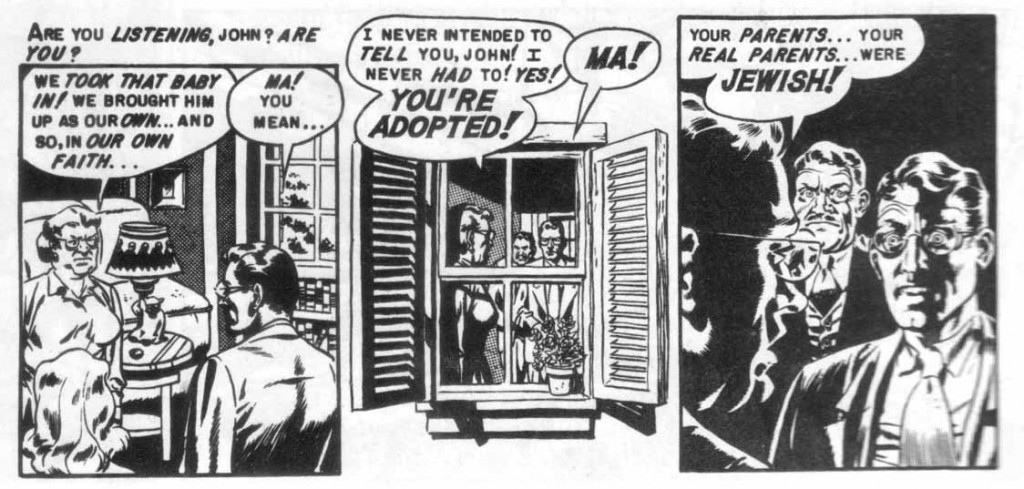

This formula of soft falsehoods and exaggeration does not confine itself merely to the topic of blacks and racism. In a public service message about drug addiction (“The Monkey”), the protagonist graduates swiftly from marijuana to barbiturates and then to the big “H” before losing control and killing his father. Devoid of any sense of irony, the story glosses over the more pressing (and common) medical and social problems associated with drug addiction, preferring to titillate its young audience with a “shock” ending. “Under Cover” and stories of that ilk are sullied by an overriding desire to simply entertain resulting in feeble if not ignorant attempts at needling lynch mobs, vigilante groups, and corrupt governmental agencies. “Hate” (a story about neighborhood anti-semitism) is a grotesque “What if you were a Jew too?” story devoid of clear ethical reasoning.

Like many modern day series, the SuspenStories comics were for and about white Americans. Stifled by a certain intellectual laziness and a chronic inability to understand their fellow non-Caucasian citizens, they unwittingly dehumanized them; presenting them as angels devoid of immorality and wretched enigmas incapable of fending for themselves. They are wholly anachronistic as far as race and societal relations are (or ever were) concerned despite their worthy motives.

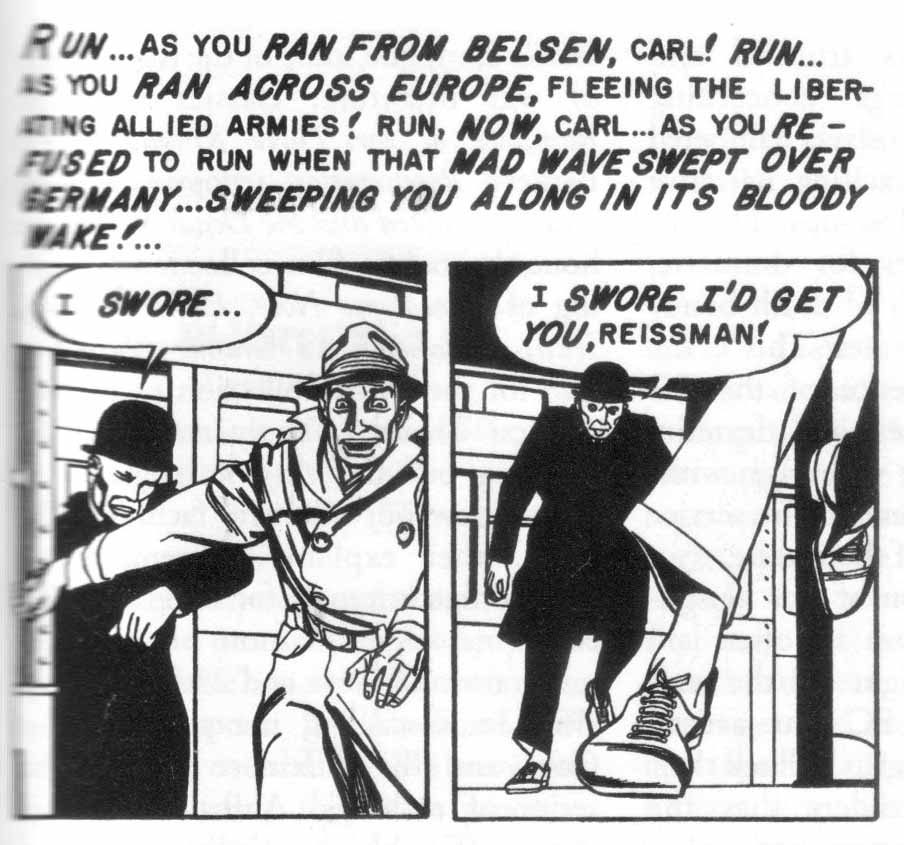

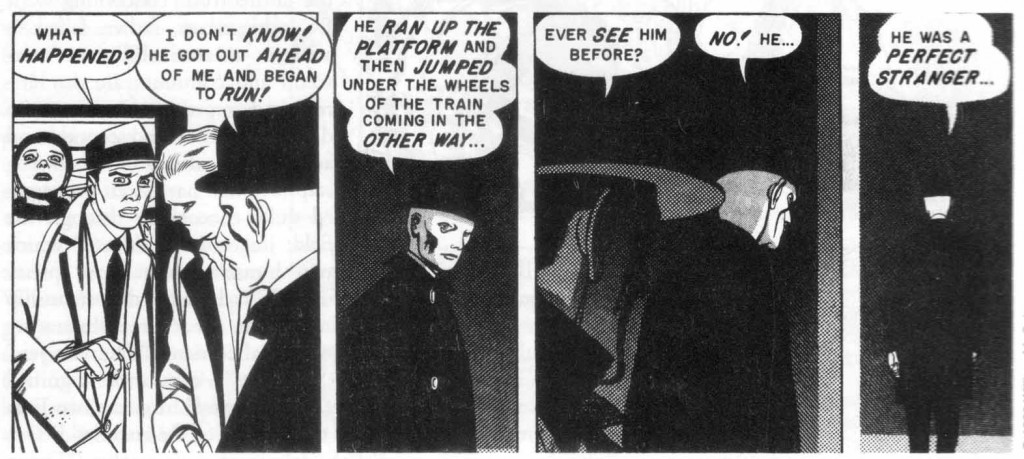

Bernard Krigstein’s “Master Race”

At one point in his famous essay concerning Bernard Krigstein’s “Master Race”, Art Spiegelman lets slip a telling comment amidst his effusive praise for the technical wonders of Krigstein’s story—he labels the subject matter of “Master Race”, “a thematically mature one for comics.” Thirty years on, this remark presents itself as almost a plea to his readers to give Krigstein some credit because he and Feldstein were tackling something a bit more challenging than the average children’s comic.

Feldstein himself was more realistic about his story, labeling it merely “good” with Krigstein “[improving] the art end of the story so much that I thought we were really breaking new ground.” Yet a feeble story, no matter how masterfully executed, should not be excused on the basis of mere thematic maturity, the very minimum basis of any adult work of art.

“Master Race” is, however, a children’s story. Perhaps a good (and this is certainly not indisputable) children’s story but still a children’s story. As a children’s story, it does not contain one iota of the humanity found in a thirteen year old girl’s famous diary during World War 2 enshrouded Amsterdam. It is pathetic that it should still be considered one of the finest stories ever created in comics.

One may wish to focus on the formalistic brilliance of “Master Race” to the exclusion of all other indicators of its decrepit nature, yet style and content cannot be divorced in what is clearly a narrative story. “Master Race” is not an exercise in pure experimentation like Richard Maguire’s “Here”, nor do such forays into experimentation and formalism forbid coherent, fully evolved content. Is it not possible, for example, to find substance in Godard’s Weekend or Bunel’s Discrete Charm of the Bourgeoisie?

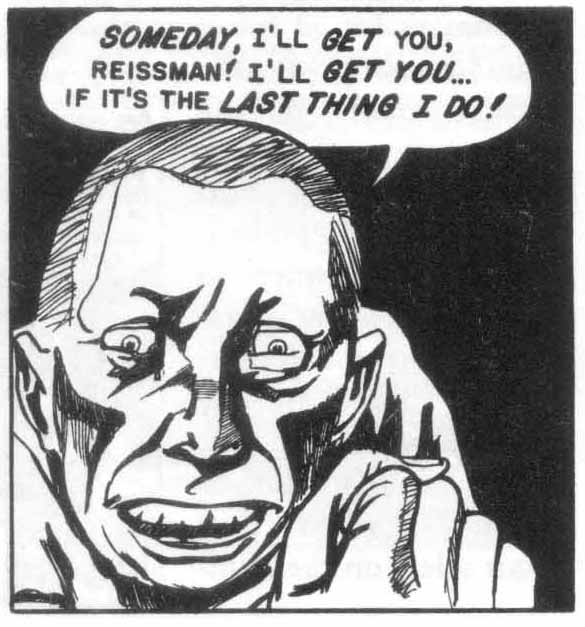

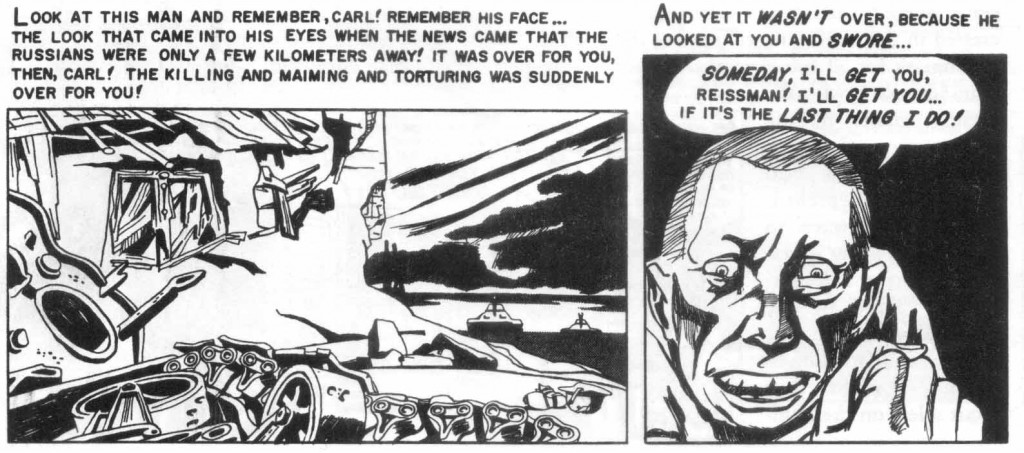

“Master Race” is revolutionary technical achievement illustrating banal sentiments. It is firmly entrenched in a certain hypersensitivity emanating from the protective glands of overbearing conservative adults and fails to extricate itself from a desperate adherence to the judicially blissful endings so typical of the EC line as a whole. In Feldstein and Krigstein’s make-believe world, revenge is consistently attainable and satisfying. “Master Race” is a deceitful fairy tale where every Jew has the chance to be an avenging Simon Wiesenthal and where Nazis don’t turn up healthy and wealthy on the political scene in Austria or as aged businessmen in France. All of which is perfectly fine for a middling children’s story but not for one of the greatest works ever created in comics.

There can be no room for excuses in judging the absolute worth of a story which is no more than 50 years old and created at a time when people were already steadily being made aware of the horrors of the holocaust. Great art doesn’t need excuses. Goya’s famous print series,The Disasters of War, is often cited in comics circles as one of the finest examples of the printmakers art (and perhaps a distant cousin of the cartoonist’s art). What we hear of less often is that Goya started his print series (amidst the chaos of the Spanish nationalist insurrection and Peninsular War) by scavenging for copperplates upon which to engrave. It was a series that was initiated from personal need and distress with little consideration for the economic realities of the time. Goya realized that he would never see the publication of his print series during his lifetime and it was only released 50 years after his death.

Truly great art is not shackled by commerce. It is born of a great artist’s insatiable need to create and to tell the truth. There is an artistic impulse behind “Master Race” but it is vastly inferior to that which we should expect of a master of the form. The constraints of entertainment and commerce have housed the work in mediocrity. No one should consider “Master Race” anything other than an above average cave painting on the path to greater things. An important first step perhaps but not one of the greatest works of comics art ever made. There is more to admire in Giotto than mere technical ability and perspective, more to Citizen Kane than a kaleidoscope of sumptuous camera angles, moody lighting, tracking shots, and deep-focus shots.

Krigstein had neither the desire nor capabilities to develop beyond “Master Race”, “The Flying Machine” or “The Catacombs”. Van Gogh stuck with his visions till the bitter end and Goya completed The Disasters of War with no sure knowledge that it would reach an audience. Krigstein, on the other hand, doesn’t appear to have kept his faith in the artistic possibilities of comics. At the very least, he did not act upon any remnants of this faith that remained following his departure from commercial comics. Nor did Krigstein show any clear genius for writing. As a consequence of this, he remained hampered by the mediocre to poor writing he was saddled with throughout his career.

The EC artists never felt themselves part of the rich tapestry of world art but merely as dedicated craftsmen. With these values in tow and without the unpredictable fortunes of genius, they failed to produce works of lasting importance to civilization. A high ideal perhaps but one which a nascent art form needs to grasp at as tightly as possible.

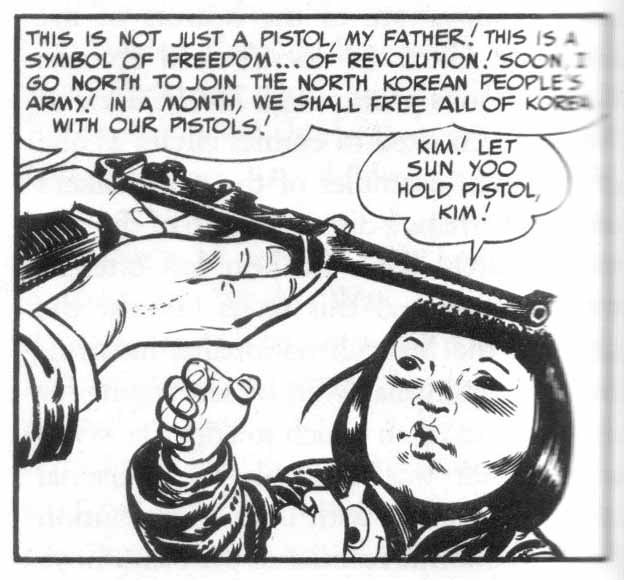

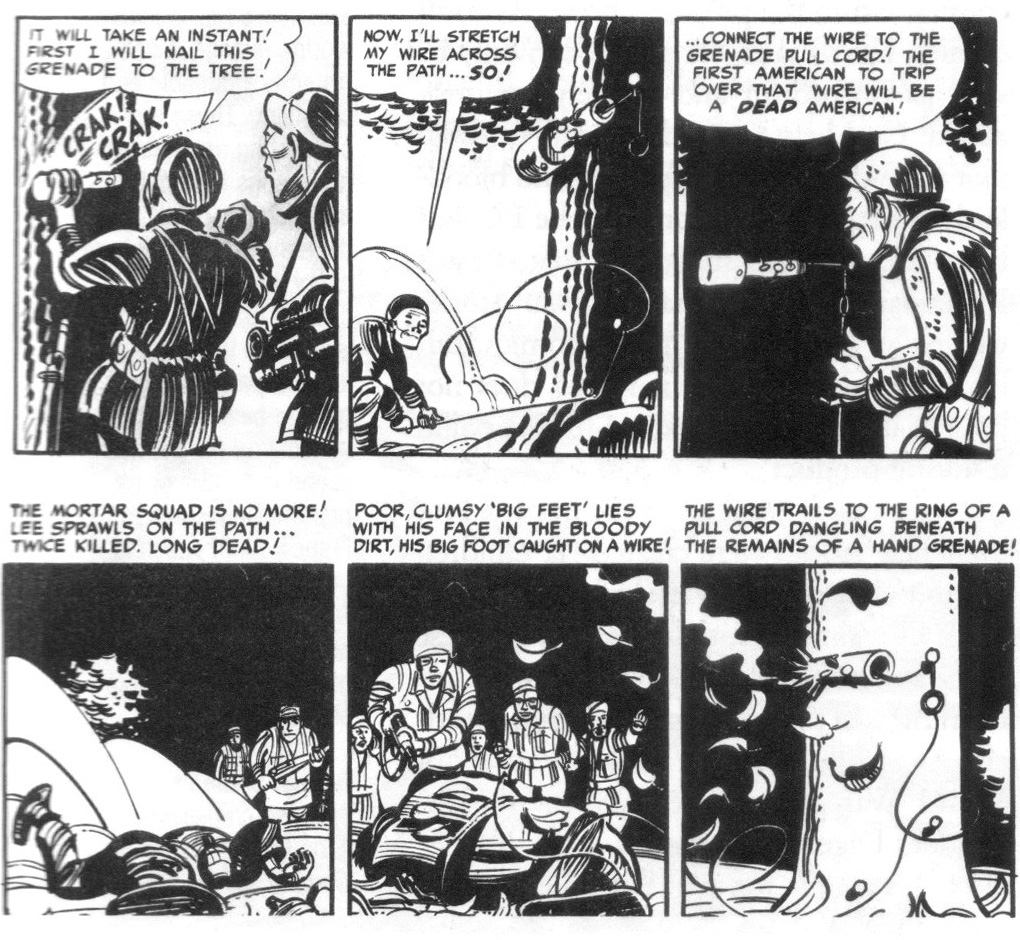

The EC War Stories

There is little doubt that the war stories of Harvey Kurtzman form a more solid foundation than the EC horror and science fiction comics.

Burdensome as it may seem, I must reiterate the often neglected fact that the EC War comics must be viewed as children’s literature. I do not say this in a derogatory way but in order to set our discussion of these comics within the proper context. As adult comics, Kurtzman’s war stories can only be seen as untruthful and severely compromised; God help us if adults truly believed that war was as gentle, dignified, and bloodlessly pleasant as the stories of the EC War line. It has been suggested that it was Kurtzman’s decision that his war stories weren’t as grisly as the horror comics, but his squeamishness in this regard does not present itself as a valid excuse for the pallid resulting product.

And this is the crux of the matter: not that these stories were created for children but that they glorify by exclusion and by failing to relate life’s simple truths. In so doing, these comics commit the grievous sin of misinforming and patronizing their young readers. As a child, the first book I read about World War 2 was the 1969 edition of Reader’s Digest Illustrated History of World War 2, a simple tome of articles that chronicled with photos the horrors of Buchenwald and the horrendous deaths on Iwo Jima and Guadalcanal. I was neither frightened nor permanently scarred in the process. Children are not the fragile, ignorant creatures we think they are, nor are they incapable of understanding the mere realities of human existence.

Once we recognize this, we must begin to wonder why some of the most esteemed critics in the field so often choose to place these comics over any other series of adult war comics. Do we find Joe Sacco’s truthful and engaging writings concerning Palestine and Yugoslavia hampered by his lack of exciting narrative technique and close-ups? Do our healthy appetites for dramatic, swanky portrayals of death betray our immature desires? This is the corrupting influence of the EC War line: artfulness and dexterity in place of truth; voyeurism without horror; content in the service of style instead of the reverse.

In recognition of this ill-concealed fact, excuses are often laid out to add weight to the deft artistry of the EC war artists. Critics and apologists will tell their half-informed readers that the depictions of war were not consistently glamorous nor the deaths steadfastly patriotic in contrast to the other war comics of the time. But such comments fail to reveal the entire truth concerning what EC achieved or, rather, failed to achieve—an inability to transcend and communicate the horror and repugnance of stories drawn from first and second hand accounts, resulting in misleading staples which have been propagated quite thoroughly through the field: jingosim (see “Contact!”; which Kurtzman himself admits was “pretty dreadful stuff”); dramatic draftsmanship and intelligent structure illustrating inconsequential content (“Thunder Jet”, “F-86 Sabre Jet!”); exquisitely dignified corpses (“The Caves!” from the Iwo Jima issue); …

… the poverty of the enemies’ beliefs and the failure of their resolve (“Dying City!”);

…sanctimonious depictions of the plight of good, honest, salt of the earth Koreans (Southern presumably; in “Rubble!”); retribution for cowards (“Bouncing Bertha”), traitors (“Prisoner of War!”) and grinning, nefarious enemies (“Air Burst!; were there ever any breathing, happy North Koreans at the end of each story?).

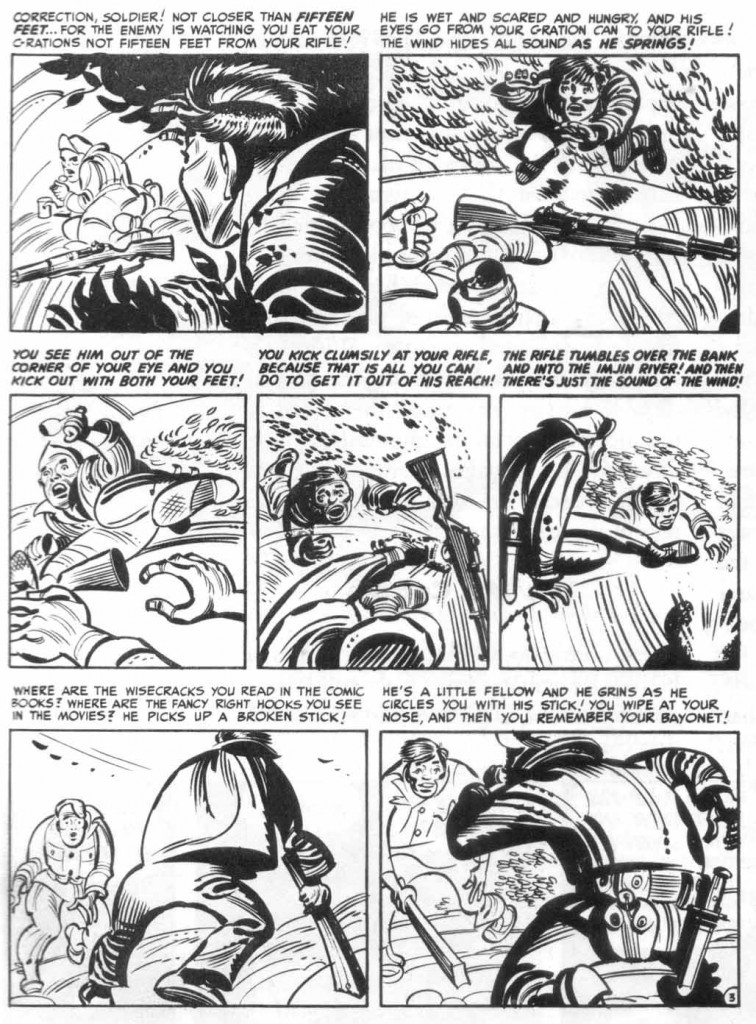

As Walter Benjamin put it, “Children want adults to give them clear, comprehensible, but not childlike books. Least of all do they want what adults think of as childlike. Children are perfectly able to appreciate matters, even these may seem remote and indigestible, so long as they are sincere and come straight from the heart.” To a certain extent, Kurtzman managed to achieve these ends in stories such as “Big ‘If’!” and “Corpse on the Imjin” but they are the exceptions—exceptions which sadly persist in gaudily adorning themselves with too much artifice and too little truthful, engaging emotion.

Shouldn’t we entertain a degree of embarrassment for placing the EC War stories alongside some of the finest works of war literature; classics like The Romance of the Three Kingdoms, Pat Barker’s Regeneration trilogy, Catch-22 and The Naked and the Dead? Would we honestly trade a film collection consisting of Apocalypse Now, Paths of Glory, Ivan’s Childhood, La Grande Illusion, or Ran for the entire collection of EC war comics? There is simply no excuse for allowing our unseeing nostalgia to so overshadow our aesthetic faculties. The only other explanation remains an overindulgent respect for some acknowledged masters of the form.

I return to Goya and The Disasters of War. Fred Licht in describing the modernity of Goya and the difference between his series of etchings and Anibale Carracci’s images of public hangings and Jacques Callot’s Troubles of War, states that

“…[Goya] forces us to see with our eyes, not with his. The critic who draws attention to Goya’s ability as an artist actually does Goya a disservice. Images such as these are clear evidence that the artist intends to be exclusively preoccupied with the unbearable inhumanity of what is happening before our eyes. In the face of what happens all around us, the talent and the ingenuity of the artist seems trivial.”

And yet here we are, over a century later, still enmeshed in debates about the merits of dramatic structure and pacing in Kurtzman’s stories about war. And why are we still here? Simply because there is little more to suck from these stories than this. As factual and humanistic documents, they are empty and irrelevant; so bereft of revelatory truths for children that they have become obsolete.

One hopes that we will soon be reaching a turning point in comics; a point at which one can look back at these comics of our youth and say with honesty that they were mediocre, even as children’s comics. A point where we can truthfully say to ourselves that we’ve grown up, that we now understand and appreciate the complexities and emotional depths the best works of narrative art should communicate. We’ve been mucking about in the sandbox for long enough.

[The EC War comics are discussed in greater detail in Part 2]

__________

Click here for the Anniversary Index of Hate.

When you look at too much crap, you draw crap. When you read too much crap, you write crap. When you listen to too much crap, you compose crap.

Years of mass-produced, ubiquitious pop culture has produced a bumper crop of stunted artists, writers, musicians and most important, audiences.

But enough of hate, let’s talk … rage. Let’s rage against the rage! Screw Orwell, gimme Petronius.

Some of the inking on the above pages is exquisite.

“Some of the answers to this question are quite apparent, among them a blindness and mule-headedness born of nostalgia. These are rose tinted lenses that have adhered so tightly to the eyes of most comics critics that they cannot be eradicated without immense difficulty. Suffice to say, the judgements made by critics and readers in assessing their favorite art form are firmly entrenched in their childhoods.”

Childhoods? In the early ’50s? I love the EC line, but I wasn’t even born when they shut down; And I’m 57.

Your argument really doesn’t wash, Suat.

They are kids comics though. I don’t think it’s crazy to suggest that people read them as kids. I know my (very limited) exposure to EC came through Mad reprints when I was 8-10.

This is an impressive piece of hate…and I mostly agree. The stories in most of the EC comics that I’ve read (including “Master Race”) don’t really add up to a whole lot. I’m still a fan of those early MAD’s…but I am enmeshed in American pop-culture detritus… Some things don’t translate very well… but that doesn’t mean they’re bad. Most comics are pretty bad, however,…and other than MAD, I would say the EC line wasn’t really much of an exception.

Yeah…I’ve tried to read Master Race and a couple other EC things and my eyes just glaze over. Even the panels Suat reprints here…that omnipresent overheated narration makes me want to run (not walk!) in the other direction.

I still think Superduperman is pretty funny, though….

Re: the “extraordinary paucity of long form works of comedy”:

This certainly seems true, although I would lobby for adding Groo to the list. I do wish more long-form comedy comics were around; why can’t something like James Kochalka’s Superfuckers or Nextwave run for 100 issues? The closest thing we have are hybrids, or series that start out funny and slowly turn into something else, like Bone or Garth Ennis’ The Boys. Where’s our Cromartie High School or Dr. Slump? I guess the best option at the moment might be webcomics: Axe Cop, Achewood, and Oglaf are some examples that come to mind, and I know there are many, many more…

I read and enjoyed many of the horror and sci-fi stories for the first time only a few years ago (the war and humor titles don’t appeal to me). The in-your-face moralizing is at such a level that its crassness, along with the clunky art and writing, is a source of entertainment, not unlike 50s melodrama and sci-fi movies. Maybe the true target of hate here should be those adults who treat this stuff seriously, not really the stories themselves.

“Maybe the true target of hate here should be those adults who treat this stuff seriously, not really the stories themselves.”

That actually is where Suat is directing most of his ire, though, isn’t it? He’s not saying these comics are irredeemably bad; he’s saying that they’re really overrated.

Longform comedy; there definitely is a fair bit in comic strips (Bloom County, Doonesbury, Peanuts.) Comic books less so — though the Giffen/DeMatteis JLA maybe qualifies. Cerebus early on, but it sort of sheds the humor… And there’s the Tick….

While it is hard not to agree with some of the arguments put forward here, it seems to me that the desire to go against the grain leads to some distorted evaluations.

I have to confess first that I fit in the nostalgia pattern, having discovered most of these stories is beautiful black and white French reprints, when I was about ten. While acknowledging this possible bias, I have to disagree with this evaluation of the Bradbury adaptations, for instance:

“These retellings do not bring us fresh perspectives or revelations and exist as insignificant appendages to the original storie”

“There will come soft rains” and “The million year picnics” are much better works in the EC versions than in Bradbury’s somewhat overrated prose. In both cases, the original story reads as simplistic morality plays, devoid of affect or of any sense of history. By contrast, the EC version fully realize the narrative universe and in doing so, enrich and enlarge the tale beyond its original and pretty trite message. Wood’s structural and design choices in “There will come soft rains” certainly bring a “fresh perspective” to the work. Both stories might have been better if the artist had had more liberty with their layout and lettering choices (though the regular grid serves “There will come soft rains” well), but to dismiss them as “insignificant appendages” is blunt and misguided.

Since these are the stories I am the most familiar with, along with the early Mad, it tends to cast a shadow on some of the judgments passed here, convincing at first glance as they may be.

(for the record, I discuss “There Will Come Soft Rains” as adaptation at greater length, in French, here : http://webtv.u-bordeaux3.fr/sciences/transverses-2011-des-hommes-et-des-machines-7)

Evaluative comics criticism has an appalling quality. Both TCJ’s list and the HU’s list convinced me that this artform deserves to die and be forgotten forever…

Re: “Mad” and being ‘outside of Western context’.

I remember trying to read Mad from the very beginning couple of years ago. I, at a time, was a 23-year old Russian (Soviet-born, obviously) woman. My interst in Mad was sparked by two different things: first, its obvious historical and cultural significance, and second, the fact, that it was Mad Magazine that ‘started’ English-language comics for me (in the early nineties my mother took me with her on her month-long work trip to Canada, where we were staying at her colleague’s house. Said colleague had a teenage son and I, barely speaking never mind reading English then, went through his stack of magazines).

So, those early issues? Borderline unreadable.

I mean, the art was obviously good, but neither the text, nor most of the visual gags did anything for me. It was obvious, that these things were all parodying something, and maybe for those familiar with the original works it was funny, but for me? No. “Superduperman’ got a chuckle out of me, so did couple of others but the rest (including ‘Starchie’, ‘Batboy…’ and the Wonder Woman parody) left me cold. As soon as Mad Magazine began, reading became much, much smoother.

Mahendra: I know you’re not a Buddhist but some of your recent comments have this Zen-like quality.

Alex: But when did you read your first EC Horror/War comics? I read most of the early Kirby FFs and Ditko Spideys well after they were first published but during my childhood as well. I grant that nostalgia is not the only reason why people like the EC line but it’s one of the least “offensive” reasons. Charles cites another reason: their pleasurable “clunky””crassness”.

Noah: Don’t you think you’re cheating by including gag-a-day cartoon strips with no evidence of a beginning, middle, or end? (Obviously not) Maybe Doonesbury counts.

Nicolas: You could be right about the two Bradbury stories you mention. It’s been a long time since I read them so I could change my mind. I didn’t spend much time discussing Weird Science/Fantasy because they’re probably the least respected comics among the EC New Trend line. Apparently, the EC editors were the most proud of them but….nowadays, most of the time, all you get is praise for Wally Wood and citations of “Judgement Day”.

Jaelinque: I did remove a sentence stating that the early Mad issues were unreadable but only because it seemed repetitive. So I obviously agree. I’m actually familiar with most if not all of the pop artifacts being parodied but in order to like the early Mad stories you actually have to care about them. And who gives a shit if you make fun of Tarzan, King Kong, Blackhawk, and Dragnet etc. Presumably kids reading Mad during the 50s?

Krigstein had neither the desire nor capabilities to develop beyond “Master Race”, “The Flying Machine” or “The Catacombs”.

Didn’t Krigstein try to adapt The Red Badge of Courage?

Suat, I wasn’t quite sure whether I was cheating or not! Bloom County had continuity and development, at least; I think it makes sense to see it as a long-running serial as much as (probably more than) Ranma. FWIW.

He did but all I’ve seen are preparatory layouts and sketches. I don’t know if a move away from original content towards Classic Illustrated-type comics can be considered an advancement though.

I think Ranma is pretty unfunny as well. Give me Asterix any day.

I like Bloom County better than Asterix, I think, and Asterix better than Ranma. But Ranma is still really funny.

one of the proofs offered at how abysmal these comics are is their failure to generate serious discussion. but luckily you have bravely waded in for yet another HU pompous thrashing. Lord knows if no one is seriously discussing a comic, it must be crap, and you’ve now confirmed the crap by seriously discussing it. right.

every time i strike this site off my reading list, eventually i think perhaps i have overreacted. then i stop by, like today and find an epic length article trashing everything EC ever entertained people with, another article that simply reprints some comments that state that all comics are crap, and an article explaining why several lauded works are overrated or down right crap. gotta hand it to you, remarkably consistent.

Why can’t I keep it straight in my head that you people despise comics with an unholy fury and the only thing you like more than just patting each other on the back for so wisely recognizing that comics are crap is engaging in elitist, yet generic intellectual futzing(and then congratulating each other about being so erudite).

I’d almost feel terrible that you are forced to read comics year after year, feeling the way you do. almost.

I and all concerned at HU have been duly chastised. Though we cannot promise to hate less, we always hope to hate better.

Noah: Cerebus went through some dour, humourless periods, but stayed largely comedic right until the bitter end, where even the title character’s (long foretold) death and afterlife fate are played for laughs. Big chunks of the last five years were given over to parodies of Spawn and Jack Kirby, and routines with the Three Stooges and Woody Allen. What is true is that, starting more or less with High Society, Sim sought to do other things in addition to the comedy, but there was still a lot of comedy for most of the rest of it.

On long-form comedy in general: Deadpool is intended as comedy, right? (I’ve never read any.)

I first read “Master Race” via the 1971 Nostalgia Press EC reprints, which means I was about 17. At the time, I thought it was a brilliant combination of story and art, and almost a generation ahead of its time.

Since then, I’ve re-read the story several times (though not recently), and I don’t think my overall opinion has ever changed.

I don’t think my view was ever colored by nostalgia, or some slavish fondness for Krigstein’s work. The fact is, when I first read it, I wasn’t some wide-eyed 10-year-old, and I hated Krigstein’s art. In fact, I think “Master Race” is the ONLY piece of work by Krigstein I’ve ever liked.

But as I alluded to in a previous thread, if “Master Race” was the ONLY iconic piece of work Krigstein ever created, it STILL puts him head and shoulders above most most of his peers who have NO iconic work in their resume.

“Childhoods? In the early ’50s? I love the EC line, but I wasn’t even born when they shut down; And I’m 57.”

It’s safe to say that the “sterling” reputation EC has accumulated over the years has been maintained by adults who were first exposed to it as children. Besides mainstream fandom itself many of the underground guys were of course hugely influenced by EC, no doubt to their detriment. Being better than the other publishers in this industry isn’t exactly a confirmation of artistic validity.

“Krigstein had neither the desire nor capabilities to develop beyond “Master Race”, “The Flying Machine” or “The Catacombs”.”

Well, he was stymied by Gaines and the editors from branching out into something more ambitious, wasn’t he? Wasn’t that the reason he quit? Not that he would’ve necessarily improved with full creative freedom, but….

“there is an extraordinary paucity of long form works of comedy.”

All I can think of right now is “He Done Her Wrong,” which might be ok at best but nothing that exactly redeems the medium.

Suat, I’m curious how you think “Blazing Combat” compares with the EC line. Not terribly familiar with the former but the impression I have is that like EC it’s only the artwork that’s of any interest.

And I gotta say, I really love this cover. Just can’t bring myself to read my reprint copy.

Maybe Noah will let “idleprimate” do a post on how much he hates HU?

Richard Cook has a review of the Blazing Combat reprint on this site. It sounds perfectly horrible.

I don’t remember much of what I’ve read of it so am in no position to offer an opinion other than that. Less wordy but similar plotlines? I’ve generally heard nothing but good things about it otherwise (but I don’t believe any of it).

———————–

AB says:

“…the judgements made by critics and readers in assessing their favorite art form are firmly entrenched in their childhoods.”

Childhoods? In the early ’50s? I love the EC line, but I wasn’t even born when they shut down; And I’m 57.

Your argument really doesn’t wash, Suat.

————————

And I never saw any EC comics pages until encountering some in an Art Spigelman article about comics in “Esquire” (which reprinted the last page of “Corpse on the Imjin!”, and a few scattered panels).

It took many years until I could see more; and far longer until I could get some of the “pamphlet”-style reprintings. (Never was able to afford the hardcover collections.)

My opinion, even back then? Strikingly different, far more powerful than anything going on in modern comics. Oddly retrograde in some ways: the heavy blocks of mostly-redundant copy squishing down the visuals quite a contrast to the far more airy, kinetic stuff to be seen elsewhere. But, what a difference in their often-fevered tone to modern comics! And that art sure was exquisite…

Another way in which the argument not only doesn’t wash, but is a veritable sewer pipe gushing out crud, is in the fashion that an impossible dichotomy is set up.

Setting up his forthcoming, apparently more kindly “Part 2” appraisal of EC’s war comics, we read:

————————-

Ng Suat Tong says:

…I must reiterate the often neglected fact that the EC War comics must be viewed as children’s literature. I do not say this in a derogatory way but in order to set our discussion of these comics within the proper context.

—————————-

…And yet, rather than using this “proper context” to ascertain the worth of these comics while considering their target audience (never mind that in reality, as Suat correctly puts it, “Children are not the fragile, ignorant creatures we think they are, nor are they incapable of understanding the mere realities of human existence”; it’s what the parents think that has the power), or wielding “presentism” like a club to attack EC for daring to bluntly criticize racism and anti-Semitism in the untraconservative 50s (how dare they show blacks and Jews as not being capable of venality too, or not depicting raging black militants)…

…Never mind that Al Feldstein was quoted thus: “…they were comics books written for fourteen-year old kids, sixteen maybe…”

Suat still lambasts the EC line for not rising to the heights of some of the greatest art and literature aimed at adults, by some of the greatest creators:

——————————-

As a kind of bible of pure comedy, the early Mad falls remarkably short of perfection however influential. Where is the personal slander, the rambunctious sex, the mad philandering, the sublime depravity and the political skewering we expect of the richest sources of comedy? Over two millennia ago, Aristophanes was brilliantly mocking the tragedies of Euripides (Women at the Thesmophoria) and risking prosecution with forthright attacks on the leaders of Athens. Contrast this with what we get in Mad. In place of Aristophanes’ unrestrained invective, Shakespeare’s poetic discursions on self-delusion, Wilde’s acute observations of social norms, and Monty Python’s Dada flavored madness we get parodies of superheroes and pulp characters…

…“Master Race” is not an exercise in pure experimentation like Richard Maguire’s “Here”, nor do such forays into experimentation and formalism forbid coherent, fully evolved content. Is it not possible, for example, to find substance in Godard’s Weekend or Bunel’s Discrete Charm of the Bourgeoisie?

…Great art doesn’t need excuses. Goya’s famous print series,The Disasters of War, is often cited in comics circles as one of the finest examples of the printmakers art (and perhaps a distant cousin of the cartoonist’s art).

…There is more to admire in Giotto than mere technical ability and perspective, more to Citizen Kane than a kaleidoscope of sumptuous camera angles, moody lighting, tracking shots, and deep-focus shots.

…Shouldn’t we entertain a degree of embarrassment for placing the EC War stories alongside some of the finest works of war literature; classics like The Romance of the Three Kingdoms, Pat Barker’s Regeneration trilogy, Catch-22 and The Naked and the Dead? Would we honestly trade a film collection consisting of Apocalypse Now, Paths of Glory, Ivan’s Childhood, La Grande Illusion, or Ran for the entire collection of EC war comics? There is simply no excuse for allowing our unseeing nostalgia to so overshadow our aesthetic faculties. The only other explanation remains an overindulgent respect for some acknowledged masters of the form.

I return to Goya and The Disasters of War…

——————————-

No, it’s not “unseeing nostalgia” or “overindulgent respect” that necessarily leads to praising (and, yes, overpraising) the EC line. Rather, it’s that some critics are evaluating EC’s achievement in the context of their time and intended audience.

————————–

Domingos Isabelinho says:

Evaluative comics criticism has an appalling quality. Both TCJ’s list and the HU’s list convinced me that this artform deserves to die and be forgotten forever…

—————————

The ultimate Domingos post!

(I feel that way about the human race, m’self…)

Suat searched an explanation to explain the inexplicable: why were these mediocre comics elevated to the pantheon of comics’ grandest achievements? Nostalgia? Sure, why not? Derik hinted at the same reason in his post (he just attacked an innoquous goat instead of a herd of sacred cows). But maybe there are other reasons… I can think of two: (1) EC Comics are seen as victims of that ugly ogre Dr. Wertham (the narrative is as follows: William Gaines was the good guy who had to fight the considerably more powerful Dr…. A plot concocted by rival publishers put EC Comics out of business… Ultimately Gaines went down because he published the work of geniuses); (2) EC Comics were great and the proof is that there’s a link between these comics and the undergrounds. In a word: it’s the beloved American Monomyth.

PS Some fans accuse others of not liking comics because they don’t like the comics they like. I wonder if it works both ways?

Richard’s review of Blazing Combat is here.

Why were these thought excellent? Because they were excellent.

I think Domingos is being generous in his explanation of why mediocrity is OK in modern comix. As is Suat.

The underlying reason is that many artists/critics/audiences prefer it. Mediocrity is the essence of pop culture and pop culture is inescapable. It’s a vicious circle: feed young people with rubbish from birth and they’ll learn to prefer it, to praise it, to protect it. It’s cheaper & quicker to make crap and the profit margins are higher, thanks to volume.

People love crap which is why this particular Hate Week is so darn good. Let us drip our mordant venom upon the squirming flesh of the proles to the tune of a Boccherini fandago which would just make their ears bleed anyway.

Mahendra, why didn’t I invite you to this? I’m an idiot.

We still have a couple weeks to go if you want to participate; email me?

The one-sentence review of Blazing Combat could be “pretty to look at, but not much substance.”

I used to enjoy the EC horror comics as a kid, but mostly because it felt like I was reading something that my parents would not approve of. I think the faint whiff of rebellion is a big part of their appeal to kids.

Mahendra: that’s undoubtedly true. Countless hours of media transmitted viral dreck provoke ADD and an addiction to mindless “fun” that’s impossible to fight.

Oh and that rebellion thing is the American Monomyth.

The myth of a perpetual, socially-acceptable rebellion is the sweetest revenge yet of conservatism upon romanticism. I’m starting to like this Western Civilization after all …

The so-called rebellion made huge fortunes…

To further emphasize what’s wrong with Suat’s condemnatory technique in “EC Comics and the Chimera of Memory”:

Imagine putting down Herriman’s universally-admired “Krazy Kat” for not being as complex as Kafka; attacking “Little Nemo in Slumberland” for not having the surrealistic sophistication of Max Ernst, the wit of Magritte.

…Then dismissively characterizing those who admire these comics as motivated by the rosy glow of childhood nostalgia, or undue, automatic reverence for their creators…

——————

mahendra singh says:

…Mediocrity is the essence of pop culture and pop culture is inescapable. It’s a vicious circle: feed young people with rubbish from birth and they’ll learn to prefer it, to praise it, to protect it. It’s cheaper & quicker to make crap and the profit margins are higher, thanks to volume.

——————–

That earlier “pop culture is based on hate” is an absurdity; however, I’d certainly agree about the “mediocrity” angle. How else can you consistently appeal to the lowest common denominator, than by “dumbing down”?

(The “consistently” is there because some fine work occasionally manages to be a popular hit as well.)

And, hey, there will also be noxious critics like Pauline Kael who rave over the greatness of pop ephemera. (And thus flatter their target audience.) Two from Kael:

“Movies are so rarely great art that if we cannot appreciate great trash we have very little reason to be interested in them.”

“Trash has given us an appetite for art.” (Yeah, like junk food leads to a craving for subtle, sophisticated cuisine…)

…Thus, when she wants to praise a masterwork like Citizen Kane, she must say: “The conceptions are basically kitsch…popular melodrama–Freud plus scandal, a comic strip about Hearst.”

“…as Adler noted…[Kael] is a critic who…turns herself into a pretzel to stun the reader into agreement that a worthless film has moments that outshine, and outmerit, actual masterpieces, if for no better reason than that the film was made by one of the directors she routinely fawned over, like De Palma…”

-Gary Indiana

“Not long before she died, Pauline remarked to a friend, “When we championed trash culture we had no idea it would become the only culture.’ ”

-Paul Schrader

(The previous two quotes from http://blogs.suntimes.com/scanners/2007/02/prose_and_cons_critics_on_kael.html )

Mike, the thing is…there’s a reasonable argument to be made, I think, that Krazy Kat is as sophisticated as Kafka. I don’t even like Krazy Kat all that much, but Herriman definitely had depths and layers. As for Magritte…I don’t actually find him all that witty, and I think Little Nemo is certainly more visually impressive, and even more visually adventurous and experimental than Magritte by a good bit. It’s not even really close.

I think Nemo (which I love) and Krazy Kat (which I don’t like that much) both seem a lot more conceptually realized than the EC titles do.

In any case, if you’re arguing that the EC titles are okay for children’s literature, and shouldn’t be thought of as major artistic achievements, I don’t think you and Suat have anything to disagree about.

Suat doesn’t need me to talk on his behalf, but I think that you’re wrong in your last paragraph, Noah. Suat views children’s art and literature as capable of sophistication as adult art and literature. It’s just that EC isn’t it…

Yes, it is.But you need to be capable of realising it.

————————-

Noah Berlatsky says:

…I think Little Nemo is certainly more visually impressive, and even more visually adventurous and experimental than Magritte by a good bit.

————————–

Sure; Magritte was deliberately low-key, cooly illustrative in his art; that the weirdness or concepts (“This is not a pipe”)would stand out more starkly.

And one could likewise maintain — accurately — that “The Matrix” was “certainly more visually impressive, and even more visually adventurous and experimental” than virtually every film (“Persoma” an exception) by Ingmar Bergman. But, does that make it a better movie?

————————–

…I think Nemo (which I love) and Krazy Kat (which I don’t like that much) both seem a lot more conceptually realized than the EC titles do.

—————————

I don’t much care for either Nemo or Krazy, but their virtues are clearly apparent. (The latter clearly by far the greater work.) But, I’d certainly agree with you there.

—————————-

In any case, if you’re arguing that the EC titles are okay for children’s literature, and shouldn’t be thought of as major artistic achievements, I don’t think you and Suat have anything to disagree about.

—————————–

I’d agree with “shouldn’t be thought of as major artistic achievements.” But, there is plenty of aesthetic worth and great creators out there in the non-comics world that can’t hold a candle to “The Disasters of War,” Giotto, “Citizen Kane,” Shakespeare, Aristophanes.

(For instance, “The Treasure of Sierra Madre” is no “Cries and “Whispers”; Bellows’ “Stag at Sharkey’s” [ http://www.artchive.com/artchive/b/bellows/sharkeys.jpg ] can’t hold a candle to Goya’s “The Shootings of May 3, 1808” [ http://history.hanover.edu/courses/art/goyamy3.jpg ]; Wilde’s “The Importance of Being Earnest” is a frothy trifle compared to the black-as-pitch acidity of Twain’s “The Mysterious Stranger” [ http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Mysterious_Stranger ]. Yet, don’t all these “also rans” have plenty of aesthetic worth of their own?)

To put down EC for not rising to those rarefied pinnacles is an easy way to claim the “snobbier than thou” throne. Speaking of which:

——————————–

Ng Suat Tong says:

A few decades later, the EC line occupies no less than 4 spaces in The Comics Journal’s Top 100 comics of the century list, a ranking exercise which should put paid to any claims that this magazine has an elitist stance.

———————————

Well, if TCJ’s list had been the “Top 100 works of art of the century,” I’d have been ready to toss brickbats, too. But it wasn’t.

———————————–

Domingos Isabelinho says:

Suat views children’s art and literature as capable of sophistication as adult art and literature.

———————————–

My knowledge of children’s literature is awfully sparse — I didn’t read it, even as a kid — but I gather that the wonderful “Where the Wild Things Are,” “Charlotte’s Web,” and “The Wind in the Willows,” most of Carroll, Grimm and Seuss, are considered high points.

(And what is “children’s art”? Aside from the renderings which accompany those books, it’s not like moppets are into the “hang up on walls” kind.)

While these “high points” are better than most — likely, all — of EC, they are not even remotely “as capable of sophistication as adult art and literature.” Where is the “Waiting for Godot,” “Finnegan’s Wake,” “Gravity’s Rainbow,” “King Lear,” for kids? The moppets get “The Nutcracker,” whilst adults must do with “The Ring of the Nibelung”…

…And that’s not even taking into account that kids’ taste in entertainment is as sophisticated as their favorite cuisine…

Mike, the matrix isn’t particularly visually inventive. It’s slick computer graphics, and there’s no particular unifying vision. It’s just not that interesting.

Mike: “To put down EC for not rising to those rarefied pinnacles is an easy way to claim the “snobbier than thou” throne.”

I’m not Suat, but I had to struggle with this since day one at the ol’ CJ’s messboard, so:

The problem is not EC Comics (it is what it is). The problem are those who view EC Comics as one of the pinnacles of the art form. (According to my past experience I should know better and shut up, of course, but oh well!…)

As for children’s lit and art I know nothing about it and I don’t care, frankly… The only thing that I do know is that chidren’s comics (with a couple of exceptions) aren’t that interesting, to me at least…

Krigstein had neither the desire nor capabilities to develop beyond “Master Race”, “The Flying Machine” or “The Catacombs”.”

i dunno, in greg sadowski’s book about him there’s stuff about how “Da Kriggz” wanted to get real book publishers to let him adapt great novels — i think war and peace and the red badge of courage are mentioned. he had a vision that went beyond eight page backups, for sure.

——————

Noah Berlatsky says:

Mike, the matrix isn’t particularly visually inventive. It’s slick computer graphics, and there’s no particular unifying vision. It’s just not that interesting.

——————-

[Doofus wearing a baseball-cap backwards]: “Bullet time, dude! Did ‘Citizen Kane’ have bullet tme? …’Bridge on the River Kwai’ would’ve been a thousand times more awesome if it had bullet time!”

…But, thinking of it in more depth, “Little Nemo” was indeed — due to its episodic nature, dream-theme, the far greater sophistication of its audience (try selling a trip, er, strip [nice typo] like that to today’s newspaper readers!), the quality expected of comics art in those days, and not to mention its creator’s talent — more “visually inventive.”

——————–

Domingos Isabelinho says:

…The problem is not EC Comics (it is what it is). The problem are those who view EC Comics as one of the pinnacles of the art form.

———————–

Considering the vast amounts of drek that had been — and are — published in the field, it’s only accurate to consider “EC Comics as one of the pinnacles of the art form.”

Which, if one thinks about it, doesn’t necessarily indicate that they’re great works of art. It’s like the “in the valley of the blind, the one-eyed man is king” situation.

They certainly remain, even if tending towards text-heavy, far superior to what has become virtually all the mainstream comics fare of more modern times: superheroes. Which feature continuing characters (thus, less likely to be killed or permanently affected by a story), absurd adolescent power fantasies, a far greater disengagement from real-world concerns, rather than the more adult outlook of EC comics stories. (And that art sure is fine!)

But, compared to what many “art comics” of more recent times have achieved, EC Comics are painfully limited work, simplistic in their narrative construction, only using a small fraction of the visual repertoire that the art form is capable of.

Somewhat in the spot of historic artifacts like “The Birth of a Nation” or “Battleship Potemkin,” extraordinary for their time, highly influential, with their degree of aesthetic worth (some far more than most), yet infinitely below, say, “Grand Illusion,” “Dr. Strangelove,” “Wild Strawberries.”

—————————-

Ng Suat Tong says:

…the EC line occupies no less than 4 spaces in The Comics Journal’s Top 100 comics of the century list, a ranking exercise which should put paid to any claims that this magazine has an elitist stance.

—————————–

Consider the American Film Institute’s “100 Greatest American Movies”: http://www.afi.com/100years/movies.aspx , where “Star Wars” is 15th from the top, “E.T.” ranks just above “Dr. Strangelove” (excuse me while I hurl), a moldy item like “The Jazz Singer” presumably getting in because being the first “talkie” = greatness: http://www.afi.com/100years/movies.aspx .

At least the TCJ list, though its rankings are highly debatable (i.e., the Lee/Ditko “Spider-Man” well above Eddie Campbell’s “Alec” stories), features ‘way consistently higher quality: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Comics_Journal#Top_100_Comics_list .

There’s no excuse for both TCJ’s list and the HU’s list. If you compare them with yet another mediocre list you just have three mediocre lists, that’s all.

It’s actually not clear to me that you and Mike disagree, Domingos. He’s saying the EC titles are highly rated because the competition is weak…and it sounds like he’d prefer for the most part more high art efforts to be chosen, just as you would.

I’d agree too that that AFI list makes one recoil. I’m not even a huge Dr. Strangelove fan…but ET? Sheesh…

Maybe, but I don’t think that the competition is that weak. What happens is that the subculture idolizes the sacred cows of old. The comics comics syndrome is everywhere.

Mike Hunter sez:

Somewhat in the spot of historic artifacts like “The Birth of a Nation” or “Battleship Potemkin,” extraordinary for their time, highly influential, with their degree of aesthetic worth (some far more than most), yet infinitely below, say, “Grand Illusion,” “Dr. Strangelove,” “Wild Strawberries.”

I watched Battleship Potemkin again recently, and I think it’s easily the most worthwhile of those five films. It’s a visual symphony. The repugnant story content undermines The Birth of a Nation–particularly in the second half–but apart from that I’d say it holds up pretty well, too.

Noah–

I don’t think much of the AFI lists, although I’m a lot more inclined to fault their inclusion of all but forgotten middlebrow award-bait mediocrities like In the Heat of the Night and Sophie’s Choice than E. T..

The Sight & Sound poll results are a lot more interesting. The latest ones just came out. The critics’ list is here, and the filmmaker’s list is here. I emailed Domingos these links not too long ago, and I have to say I’m curious as to what he thinks.

Domingos–

As the organizer and editor of the HU poll, I must say I think you may be misunderstanding the point of it. I wasn’t looking to do what TCJ did, which was to more or less put together the platonic ideal of best comics lists. I don’t think that’s possible or even desirable. The TCJ list was more or less about defining the field in that magazine’s image, and we were absolutely not doing likewise here. What I wanted was to get an idea of the current consensus opinion about works in the field by the people most engaged with it. The list we put together from the votes is meant to date. “Best of” lists always do, in any case.

Man…the love for Apocalypse Now is something I’ll probably never get.

Good to see Singin’ in the rain on there though….

————————

Domingos Isabelinho says:

There’s no excuse for both TCJ’s list and the HU’s list.

————————

…It’s democracy in action!

————————

Noah Berlatsky says:

I’d agree too that that AFI list makes one recoil. I’m not even a huge Dr. Strangelove fan…but ET? Sheesh…

————————-

Even though I’ve razzed the dismissal of those who admire EC comics as simply being motivated by “nostalgia” (never mind that most praising EC weren’t even born, or mere infants, when they were originally published), there sure seems to be an extra critical glow imparted to art consumed in childhood years.

Why, in that other HU thread which veered off into the trashing of Spielberg films like “Schindler’s List” and “A.I.: Artificial Intelligence,” there was plenty of admiring bowing given to infinitely more simplistic and unambitious (even if superbly crafted, which one can take for granted with Spielberg) fare like “Jaws” and “E.T.” Making me shake my head in wonderment.

————————

…it sounds like [Mike would] prefer for the most part more high art efforts to be chosen, just as you would.

————————

At the very least (my dictionary-definition mania asserting itself again), I’d like for there to be a clearly defined list specifying that it’s for the artistically highest-level works. Not simply skillfully entertaining, or historically important, or massively popular, or influential.

But, a list just for work which is intellectually and philosophically complex, expressing a mature rather than simplistic worldview, which deploys the aesthetic “arsenal” that the art form has at its disposal in a masterful fashion.

As it is, those lists are a hodgepodge. Re The Comics Journal list, I don’t have that issue handy, so can’t confirm exactly how its “Top 100” list was introduced. But second-hand descriptions such as Wikipedia’s call it a “Top 100 Comics list,” and “a 20th-century comics canon.” The term “Top” utterly leaves out by what criteria “topness” is defined.

Re the other term, the relevant definition is “A group of literary works that are generally accepted as representing a field.” ( http://www.thefreedictionary.com/canon ).

————————

The term “literary canon” refers to a classification of literature. It is a term used widely to refer to a group of literary works that are considered the most important of a particular time period or place…

Of course, there are many ways in which literary works can be classified, but the literary canon seems to apply a certain validity or authority to a work of literature. When a work is entered into the canon, thus canonized, it gains status as an official inclusion into a group of literary works that are widely studied and respected. Those who decide whether a work will be canonized include influential literary critics, scholars, teachers, and anyone whose opinions and judgments regarding a literary work are also widely respected. For this reason, there are no rigid qualifications for canonization, and whether a work will be canonized remains a subjective decision.

Literary canons, like the works that comprise them and the judgments of those who create them, are constantly changing …More often than not, it is those works that are considered contextually relevant that gain entry into the canon. This means that the literary work is relevant to ongoing trends or movements in thought and art, or address historical or contemporary events, etc.

Often, the popularity of a literary work is based not only on the quality, but the relevance of its subject matter to historical, social, and artistic context. A popular or respected literary work usually deals with what people are most interested in, and this interest weighs in on whether or not the work is canonized. While the text of a literary work does not change over time, the meaning extrapolated from it by readers, and thus the attention paid to a literary work may change. As people’s thoughts and experiences change, a literary work may move in and out of interest and contextual relevance. Over time, literary canons will reflect these changes, and works may be added or subtracted from the canon.

————————-

http://m.wisegeek.com/what-is-a-literary-canon.htm

Note how, though aesthetic worth is valued, it’s not considered necessary for a work to be “canonized”; that “representativeness,” “importance,” historic relevance, how a work relates to others going on in that art form in “a particular time period or place” are also significant factors.

By those latter criteria, then, EC comics richly deserve inclusion in the comics canon.

And considering how many different viewpoints were involved, no wonder that list was a hodgepodge:

——————-

The [Comics] Journal published a 20th-century comics canon in its 210th issue (February 1999). To compile the list, eight contributors and editors made eight separate top 100 (or fewer than 100 for some) lists of American works. These eight lists were then informally combined, and tweaked into an ordered list.

——————–

http://www.enotes.com/topic/The_Comics_Journal

(As long as we’re dealing with comics lists, “Rob Clough’s Top 100 Comics of the ’00s”: http://classic.tcj.com/alternative/analysis-rob-cloughs-top-100-comics-of-the-00s-part-one-of-two/ )

———————–

Robert Stanley Martin says:

Mike Hunter sez:

Somewhat in the spot of historic artifacts like “The Birth of a Nation” or “Battleship Potemkin,” extraordinary for their time, highly influential, with their degree of aesthetic worth (some far more than most), yet infinitely below, say, “Grand Illusion,” “Dr. Strangelove,” “Wild Strawberries.”

I watched Battleship Potemkin again recently, and I think it’s easily the most worthwhile of those five films. It’s a visual symphony.

————————–

And that’s about all that can be said in its favor. Aside from being lying, history-distorting propaganda (the idolized, rebelling sailors actually trained their ship’s guns on a city and threatened to massacre its innocent civilians unless the Czar gave in to their demands), it’s simplistic, melodramatic. Check out its “odessa steps” sequence, one of the most famous in cinema: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DLEE2UL_N7Qhttp://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DLEE2UL_N7Q .

Great for its time, but overwrought, flowing poorly, with unfortunate silent-movie-style emoting.

—————————

The TCJ [Top 100] list was more or less about defining the field in that magazine’s image…

—————————

Which is why , for a notoriously superhero-hating magazine, we still get these entries?

#30 The Fantastic Four by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby

#35 The Amazing Spider-Man by Stan Lee and Steve Ditko

#88 Jack Kirby’s Fourth World by Jack Kirby

“Good to see Singin’ in the rain on there though….”

The extended “gotta dance” sequence is great, of course. But the last time I saw the movie the denouement with the silent movie actress was really, really grating and overdone.

Mike: “…It’s democracy in action!”

I don’t have much respect for democracy. At least in a dictatorship you know who the enemy is. But I digress, of course…

In this particular top ten thing my beef goes to decades of status quo stating how great simplistic crap is. You know?… A lie often repeated…

I don’t think you’d have Amazing Fantasy without E.C. horror. Without that, no Amazing Fantasy #15 . . . and I think that without that story, there’d be no decades-long superhero industry, for better or for worse.

Pingback: Robot Reviews | The EC Library | Robot 6 @ Comic Book Resources – Covering Comic Book News and Entertainment

Pingback: Revisiting "Classic" Comics - Comic Book Daily|Comic Book Daily

Pingback: » Revisiting “Classic” Comics Comic Artist Network

Pingback: Must Read: The Literaries

“A few decades later, the EC line occupies no less than 4 spaces in The Comics Journal’s Top 100 comics of the century list, a ranking exercise which should put paid to any claims that this magazine has an elitist stance.”

Nonsense. The only thing this factoid proves is that the JOURNAL’s type of elitism is not the same as is practiced by Tong.

Pingback: Comics as their own thing (Campbell was right) | Wis[s]e Words

Pingback: Comics: ¿es solo contar historias? | El Teporocho Reader´s

What a shit article. EC stories were miles ahead of the other ten cent horror crap around at the time. That’s why the next generation of comic book artists and writers loved them so much, because they were the smartest, best comics at that time. Whatever crap you like now will be overrated when compared to better stuff that comes later. They were important because the subject matter was better, the art was better, the writing was better than the other crap around and it pushed other artists and writers forward, DUH. The part where you “explained” why EC stories really weren’t important/good/funny/meaningful was so farty, unconvincing, and lame.

“better than the other crap around” doesn’t mean good. And are you saying art always gets better and better over time? Shakespeare and Mozart don’t seem to fit into that argument very well…

Noah, I could kiss you.