Most of the comics I’ve consigned to the Manga Hall of Shame are there for obvious reasons: a script so hammy you could serve it for Easter dinner, for example, or a female character conjured straight from the pornographer’s imagination. But the manga that earns my greatest scorn isn’t a boob-fest like Eiken or Highschool of the Dead or The Qwaser of Stigmata. No, my least favorite manga looks positively wholesome in comparison, with a nifty cover design and a familiar corporate logo just below the title. Don’t be fooled, however: Gandhi: A Manga Biography is a bad comic.

As I noted in my original review, Gandhi has problems like a dog has fleas. The script is tin-eared, with passages of old-timey formality punctuated by California dudespeak. (One character actually calls another “bro.” No, really — “bro.”) The pacing, too, is uneven, focusing so heavily on Gandhi’s formative experiences in South Africa that his crusade for a sovereign India reads more like an epilogue than a second act. Equally frustrating is author Kazuki Ebine’s tendency to reduce major historical figures such as Jawaharal Nehru to walk-on roles; from the few panels in which Nehru appears, one might reasonably conclude that Nehru was just one more person that admired Gandhi, and not one of Gandhi’s most important proteges — or, for that matter, India’s first prime minister.

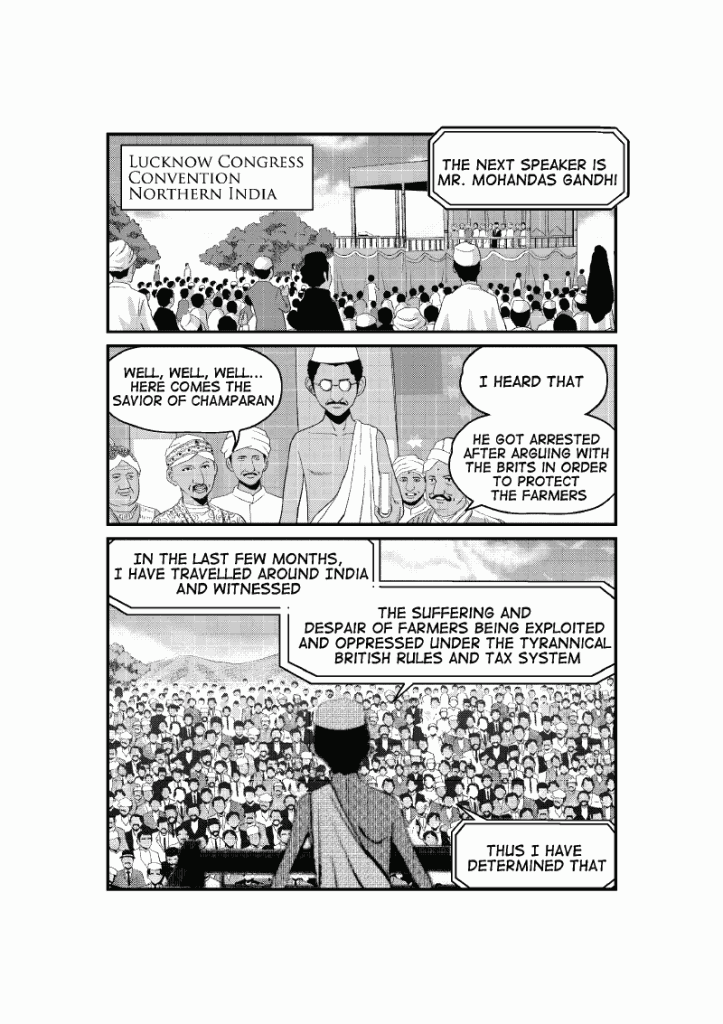

The comic’s greatest sin, however, is that it’s boring, transforming the life of a truly brave and complicated human being into a series of artlessly executed tableaux. The script, in particular, labors mightily under the weight of Gandhi’s prose, which is frequently juxtaposed with Ebine’s clumsy attempts to articulate the opposing point of view. Confrontations between Gandhi and Muslim activists, British authorities, and separatist skeptics are presented with all the sophistication of a third-grade school play, treating Gandhi’s adversaries as mustache-twirling villains and Gandhi as an unwavering paragon of virtue, always handy with a sage remark.

Ebine also struggles to tell Gandhi’s story with a meaningful sense of urgency or coherence; events are presented chronologically in brief, disconnected vignettes that rely excessively on talking heads to create continuity. Consider the following scene: in April 1919, Gandhi organized a national strike to protest the Rowlatt Act, an anti-terrorism measure that granted British authorities the power to imprison, without trial, enemies of the state. Ebine depicts a strike-day confrontation between protestors and soldiers in Amritsar, a village in the Punjab state. That massacre, however, is staged so poorly that it’s difficult to follow what happens. First we see tanks rolling through narrow streets; then we see children playing on the periphery of a demonstration; then the British soldiers begin firing on the crowd; and last, Gandhi stands over victims’ bodies, sadly shaking his head. The disjointed imagery poses more questions than it answers: what triggered the shooting? Where were the soldiers standing in relation to the crowd? How many people were present? What happened to the large number of tanks seen in the very first panel? And when did Gandhi arrive on the scene: moments after the carnage, or a day later? Neither the dialogue nor the illustrations address these basic issues, robbing the scene of its potential dramatic or explanatory value.

Then, too, Ebine does such a poor job of recreating the period and the setting that the reader never feels transported to South Africa or India. Ebine focuses most of his efforts on costumes, recreating hats and military uniforms in just enough detail to suggest the early twentieth century. His backgrounds, however, are so devoid of information that Gandhi could just as easily be taking place in modern-day Texas as in 1920s India. Simplification is a common practice in manga, but in skimping on such elements as buildings and streetscapes, Ebine misses an important opportunity to show us how Gandhi’s environment shaped his thinking, his personality, and his strategies for non-violent engagement with the British.

Contrast the sparseness of Gandhi with a historical work such as The Times of Botchan, and Ebine’s poverty of imagination becomes that much clearer. In The Times of Botchan, Jiro Taniguchi uses period detail to immerse the reader in novelist Natsume Soseki’s world: we see the uneasy mixture of Western fashion with traditional Japanese costume, and the gleaming modernity of trolleys and railway stations contrasted with centuries-old homes. Taniguchi’s drawings do more than tell the reader, “This story takes place during the Taisho period”; they help the reader understand how a writer living in that particular place and time might have produced a satirical novel such as Botchan. Ebine’s illustrations, however, are too perfunctory to convey the squalor in which India’s untouchables lived, or the segregated train cars to which Indians were consigned — details that would have demonstrated the specific social injustices that Indians faced both at home and in South Africa.

To judge from the generally favorable reviews of Gandhi, I have no doubt someone will be offended by my suggestion that Gandhi is a bad comic. But when the basic mechanics of the book are so poor, and its treatment of complex, ugly periods in colonial history so simplistic, it’s impossible to give Gandhi a pass just because the subject matter is high-minded.

__________

Click here for the Anniversary Index of Hate.

It’s interesting…at the end you say that it shouldn’t get a pass because of the subject matter. But surely the reason that this seems extra-special bad is because it’s about Gandhi, right? The subject matter doesn’t give it a pass; it makes it worse, and worth sneering at. Taking on an important topic and failing is worse than just running through genre tropes badly. Ambition can be a sin.

That’s why I think Schindler’s List is my most hated film ever. Spielberg being crap is just Spielberg being crap, but Speilberg being crap about the Holocaust is really unforgivable.

Pingback: Hatin’ on Manga at The Hooded Utilitarian

Hi, Noah!

Your comment points out a limitation of my essay: I didn’t provide a sampling of critics’ responses to Gandhi. On the whole, reviewers have treated Gandhi (and the other manga biographies published by Penguin) favorably. I suspect some of that praise stems from not knowing much about the subject; if you haven’t read a biography of Gandhi or a history of modern India, how would you know what was missing from the manga?

Some of the praise, too, stems from squeamishness: who wants to be the jerk who disses a biography about a famous pacifist? And some it reflects the “everything is more awesome in manga form!” disease that most of us manga-bloggers — myself included — occasionally come down with. (Hence the enthusiasm for manga about the founding of 7/11 and the invention of Cup Noodle.)

Outside the mangasphere, I’ve seen a lot of book bloggers give Gandhi a favorable review. I’d guess — perhaps wrongly — that their praise results from a lack of experience with graphic novels in general and manga in particular. Anyone who’s looked at licensed manga that originated in a magazine like Shonen Jump, Hana to Yume, or Big Comic Spirits would see that Ebine’s draftsmanship lacks the command of perspective and anatomy that’s expected of mainstream artists. The other issues (like the shitty translation) seem like they’d be self-evident, though, don’t they?

To address your question about ambition, yes, I agree with you that tackling a historical subject — especially one as complex as colonialism — is much riskier than writing a story about punching a man-shark in the face. I don’t know that it’s more deserving of scorn than a bad superhero comic, but it takes a lot more effort to explain what makes it bad.

Wow…okay, I didn’t realize you were bucking a (at least mild) consensus.

Are there books that have been roundly condemned in the mangaverse?

The reason that Matt went after Johns is because Johns is immensely popular an influential. I doubt he would have bothered otherwise…which I guess is sort of what I was trying to say. If you’re singling something out for badness, there has to be a hook; something that makes it worth talking about rather than all the other bad things. Generally that’s reputation (i.e., the thing is overrated)…which is apparently the case here too. But I think that choosing an important topic (like Gandhi or the Holocaust) can also be a hook of sorts.

There’s also biography, of course. Several people coming up have chosen comics that were important to them in the past for one reason or another….

Reading Gandhi, I was puzzled for example by a South Africa without a single black person. Also, some similarities with Richard Attenborough’s movie were far too obvious. (Sorry, my review of Gandhi is in Finnish.)

http://futoiyatsu.wordpress.com/2011/10/10/melkein-kuin-elokuvissa/

I was puzzled for example by a South Africa without a single black person.

Me, too. The artist’s single-minded focus on Gandhi offered an odd and incomplete picture of South Africa.

Also, some similarities with Richard Attenborough’s movie were far too obvious.

Agreed. That’s a problem with other manga biographies that Penguin has published, too: the Dalai Lama comic, for example, closely hews to Martin Scorsese’s Kundun, without capturing any of the film’s grandeur or detail. I haven’t seen the recent film adaptation of The Motorcycle Diaries, but I wouldn’t be surprised if it influenced the creator of the Che Guevara bio-manga.

Salman Rushdie trashes the Attenborough film for many of the same reasons aired here (it’s neglect of the complexity of Gandhi and his motivations—a very loose grip on the history of modern India). He even singles out the treatment of the Amritsar massacre as a particularly egregious misrepresentation of history. Of course…it won all the Oscars. Anyway, if the manga is heavily reliant on Attenborough, that in itself might make it not only derivative, but also inaccurate…perpetuating colonialist narratives even.

Rushdie’s treatment of Attenborough is in an essay “Attenborough’s Gandhi”–republished in the book of essays, Imaginary Homelands….if anyone cares. It’s an enjoyable and enlightening piece of “hate” for the big anniversary–just not about comics.

Thanks, Eric — I haven’t read the Rushdie essay, but it sounds like it’s worth seeking out!

Your comment is also a good reminder that critics should do their homework when they’re reviewing material rooted in history, or based on a novel, play, television show, etc. Almost none of the reviews I’ve read of Gandhi: A Manga Biography have questioned the accuracy of the information, or the author’s presentation of events. I am by no means a scholar of African or Indian history, but it didn’t take much research to poke holes in Ebine’s portrayal of Gandhi.

I’m not sure why this idea is so controversial in book- and comic-book reviewing circles (I’ve been “yelled” at for saying as much before), but the dearth of negative criticism in this case underscores the need for more informed approaches.

I totally agree…and Rushdie’s point is that the Attenborough film misrepresents the reasons and justifications both for various colonial atrocities (like the Amritsar massacre) and for much resistance to colonialism. He argues that the film serves various Orientalist stereotypes about India…and in doing so justifies imperialism to some degree. I’m not an expert on Indian history either, really (I know a little), but not being “accurate” will, of course, slant one’s views of history and (potentially) politics…so it’s not just a question of “fact-checking” but of ideological positioning.

I don’t know that you necessarily have to do your homework…but if you don’t know much about the topic covered, it seems like you should probably point that out. (i.e., just a sentence saying, “I know little about the War of 1812, but according to the author,” etc. etc.) At least then readers know where you’re coming from.

In theory, someone *could* write a great essay about a biography, an adaptation, or a historical drama without any prior knowledge of the topic/source. In practice, however, I tend to take a reviewer more seriously if he’s done his homework. I can’t imagine reading a review of the new Anna Karenina film written by someone who was totally unfamiliar with Tolstoy’s novel, for example — not because I’m such a purist about Tolstoy, but because I’d want to know how the movie departs from the book (which it sounds like it does), and whether that departure actually improves or clarifies some aspect of the novel or reduces it to caricature. The same goes for Gandhi: if the author has taken liberties with the historical record, I’d want to know why, and whether those liberties serve a legitimate purpose.

I agree again. I mean…if you title a book “Gandhi” and the events in it are clearly based on the real life of the historical figure….then not knowing shit about it is kind of a point against you. If you do know something, but are intentionally warping history for aesthetic and/or subversive and/or political purposes…then that might (and often does) have value…but being more or less completely ignorant about a subject…and then writing a (more or less) informational book about it…seems pretty contradictory.

Right…Kate was saying that a reviewer should know something about it…and I feel that that might or might not be necessary depending on what you were interested in or what your audience was. But you should certainly make it clear what you’re doing and why, so that (for example) folks like Kate who want to hear how Anna Karenina film compares to the book know that they’ve come to the wrong place.

As just an example of when it might not matter…I just reviewed the new Cronenberg film over at the Atlantic. It’s based on a Dellilo novel that I haven’t read…but I don’t know that there’s necessarily an expectation that I would have (I didn’t say I hadn’t I don’t think because I just suspect that many reviewers haven’t and probably most readers weren’t expecting it…I’m sure it was obvious enough since I didn’t compare the two.)

Well…there is some difference in the Cosmopolis thing. First of all, nobody else read it either…but more to the point, there’s no pretense to reference to real historical events there…It’s two fictions with the same name and maybe some shared characters and events…You can take the story on its own terms. If the text is supposedly referring to reality…some knowledge of the reality it makes claim to seems necessary. I admit though…I would prefer my Anna K. reviewer to know something of the novel…and I’d be curious about the distinctions between the novel and the film for Cosmopolis too… The major difference there, though…is that if you’re going to see an Anna K. movie, you’re probably interested in, have read, or have heard of the Tolstoy novel. My guess is that most Cosmopolis filmgoers don’t even know (or care) that there was a book. Anna K. is fetishized as one of the great world novels…that’s why it gets made into a film in the first place. The same is not true of Cosmopolis.

I had at least one commenter say that the film was fairly close to the book; you could tell that he took a lot of the language from it certainly; it’s very written for a movie.

Pingback: MangaBlog — New manga, Vampire trailer released