Earlier in this roundtable of hate Alex Buchet wrote about racism in European kids comics. Among other things, he pointed out that the skill of the rendering in this case compounded rather than excused the crappiness of the comics. Skill used in pursuit of vice is itself a vice, not a virtue.

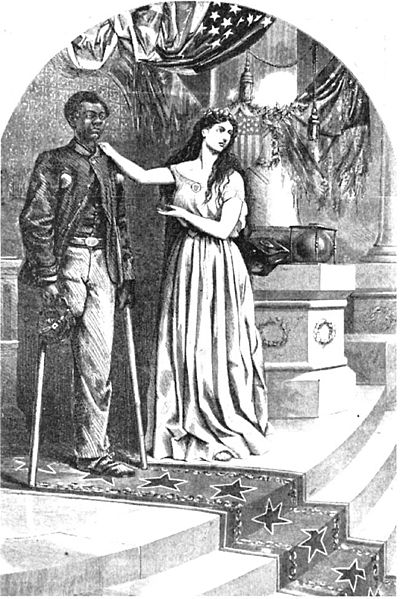

I think this also arguably applies to the work of Thomas Nast. In particular, I’m thinking of a couple of Nast’s cartoons which were highlighted in James Loewen’s excellent book Lies My Teacher Told Me. Loewen first points to the illustration below.

The cartoon was titled “And Not This Man?” and was printed in Harper’s Weekly, August 5, 1865. As Loewen says, the cartoon “provides evidence of Nast’s idealism in the early days after the Civil War.” It also shows the strong memory of black’s recent service in the Union army, and links that service directly to their citizenship, their equality, and their suffrage rights.

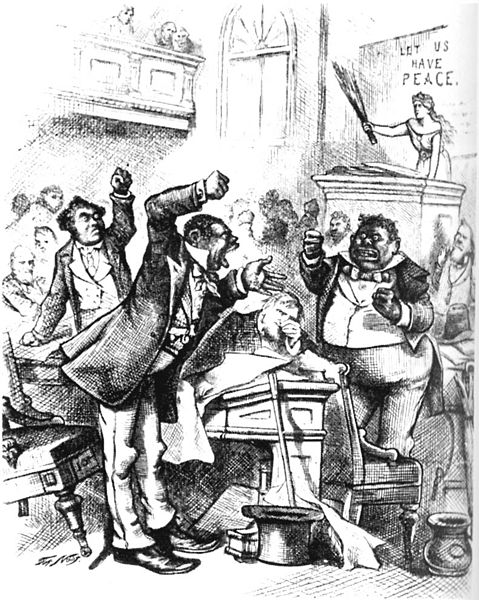

Here is another Nast cartoon, from nine years later.

This one is titled “Colored Rule in a Reconstructed(?) State.” Again, it was printed in Harper’s Weekly; the date was March 14, 1874. As Loewen says, “Nast’s images of African Americans reflected the increasing racism of the times…. Such idiotic legislators could obviously be discounted as the white North contemplated giving up on black civil rights.”

I think it’s clear enough that the second cartoon is, on its own merits, a vicious and evil racist piece of shit, which uses blackface imagery and racist iconography to (as Loewen says) justify inequality and discrimination. This sort of imagery and language was the basis for 100 years of Jim Crow. Moreover, this vision of Reconstruction still undergirds neo-Confederate sentiment and racism to this day.

But the second cartoon is only more painful when compared to the first. Sometimes cartoonists are excused their use of racist caricature on the grounds that they couldn’t have known better at the time, or that everyone was doing it back then. But, clearly, Nast did know better, and was perfectly capable of drawing black people without using caricature when he felt like it. He became more racist over time, not less. His racism was a function of his era, but it was not a function of simply living in the past. Rather, he was racist specifically because he was capitulating to a society which was becoming more racist — and not only was he capitulating, but he was actively encouraging that transformation. America betrayed its ideals…and Nast betrayed his own right along with those of his country.

And if Nast was culpable in 1874…well, it’s hard to see how Winsor McCay wasn’t culpable in the early 20th century, or how Eisner wasn’t culpable even later. Racial idealism wasn’t foreign to America; artists who were sufficiently intelligent or brave or moral had an iconographic and ideological tradition to draw on if they wanted to present black people as human. Cartoonists who chose not too — like Nast in 1874, or McCay and Eisner later — or Crumb later than that — were making a choice.

Along the same lines, I think these images show that Nast’s formal powers were deliberately and maliciously perverted. He used his considerable skills (evident even in these crappy scans) to make caricature look natural and feasible, to ridicule the weak, and to portray the Reconstruction period as one of chaos and monstrosity. If he were a lesser artist, the drawing would be less effectively racist. But even beyond the utilitarian argument, the second drawing seems more evil because we know, from the first, that Nast is capable of seeing and depicting black people as human. His betrayal is more thorough because there is a talent and a vision there to betray.

These cartoons don’t exactly make me angry the way that the comics I dislike the most make me angry. I was really furious after reading In The Shadow of No Towers, for example — the pompousness, the tediousness, the stupidity, all seemed to be speaking directly to me in a way which I’m afraid I took personally. That second Nast cartoon, though, is so old, and so clearly ideologically repellant that looking at it I don’t feel individually assaulted — just depressed and a little despairing for my country. Still, while it’s not my least favorite, I think that the magnitude and influence of its betrayal puts it in the running for being the worst comic ever.

__________

Click here for the Anniversary Index of Hate.

Good post, Noah, but could you spell my name right please? Thanks for citing me, anyway.

Crap; sorry about that. It’s fixed.

Good piece, but perhaps a little too easy, Noah? I had hoped you would open up a new, unexpected flank here…

Anyway, that image of the black legislators is very close, down to specific imagery, of the similar scene in D.W. Griffith’s “Birth of a Nation” — I wonder whether he picked it up from Nast, or whether there was a whole tradition of portraying the results of the end of slavery in this way. Probably, and depressingly, the latter…

Just for the record, Nast was comparing those black legislators with ‘the lowest whites’. Below that Harper’s cartoon, the caption said:

COLUMBIA. “You are aping the lowest whites. If you disgrace your race in this way you had better take back seats.”

http://www.encore-editions.com/colored-rule-in-a-reconstructed-state-th-nast

Theodore Wust responded with another cartoon on the cover of New York Daily Graphic, entitled “I Wonder How Harper’s Artist Likes To Be Offensively Caricatured Himself?”:

http://www.joshbrownnyc.com/hayes/53.jpg

Interesting! Thanks for that, Pepo.

It is interesting…though I don’t know that it changes my take that much….

Oh…and yes, Matthias, it’s not a super-ambitious piece. Like Suat, I have sort of a problem in that most of the things I really, really hate I’ve already written about.

I’m sort of ruminating on another post…we’ll see if it works out.

Thank you for that vital clarification, Pepo. To deliberately distort the meaning of a cartoon by omitting its caption reveals a disgraceful agenda. Noah Berlatsky belongs in the same camp as those turbaned fanatics raging, rioting, burning, and murdering against cartoons of Mohammed.

For pity’s sake. I didn’t deliberately leave the caption off; I didn’t see the damn thing; it wasn’t on the version I looked at. And it doesn’t matter; a racist caricature is a racist caricature, and the story of blacks screwing up reconstruction is false, whether they’re compared to the “lowest” whites or not, whatever that might mean.

And if you can’t tell the difference between raging, rioting, burning and murdering, and writing a blog post to express an opinion, you’re in a sorry state indeed.

Like acid in my face.

HU: attracting hysterical trolls since 2007.

Berlatsky – saying “I didn’t see the damn thing” does nothing to mitigate your position. You have had an agenda, you have produced propaganda to further that agenda, and basic research was nowhere on your to do list. Text is an integral component of all cartoons from that era. Yet you have written an article full of opinions about what an image represents without having even bothered to find out what the image was actually about.

Okay; you think I’m a monster and I think you’re ridiculous. I’m happy to agree to disagree.

BTW, the Mohammed cartoons incident IS a valid comparison. As O’laughlin explains in “Images as weapons of war: representation, mediation and interpretation”, the actual cartoons had little to do with the protests. The cartoons were just an excuse for Islamists to pursue their pre-existing agendas, and that agenda used the Muslim protestors’ pre-existing stereotypes of “Western ‘arrogance’ and ‘insensitivity’, and Muslim ‘victimhood’”. Berlatsky’s article, with vitriolic rants like “a vicious and evil racist piece of shit, which uses blackface imagery and racist iconography” parallels the rabble-rousing of those agenda-led Muslim fanatics – both draw on the pre-existing stereotypes of the intended audience, and both studiously ignore the actual purpose of the images.

Right…with the wee exception that I didn’t actually murder anyone. You do understand why that’s different, right? Or did your source fail to cover that?

As I said, I don’t think the caption actually changes the fact that this is a vile, racist piece of shit. Nast drew a vicious blackface caricature to show that blacks were incapable of governing during Reconstruction. That ties into neoConfederate narratives which were used to create 100 years of Jim Crow. If that Nast cartoon isn’t viciously racist, nothing is viciously racist. The fact that Nast compares the blacks in the image to the “lowest” whites doesn’t mitigate the cartoon; it just shows he had prejudices against (I presume) ethnic whites as well as blacks.

I mean, if you wanted to stop being a self-parody for a minute, why don’t you explain why you think the caption changes the cartoon’s meaning? I don’t really see it, but I’m happy to hear a contrary position.

I have to say, I never thought in a million years that this would be a controversial post. Blackface caricature in support of neo-Confederacy; who’s going to want to defend that, I thought? Just goes to show….

———————

Noah Berlatsky says:

…the story of blacks screwing up reconstruction is false, whether they’re compared to the “lowest” whites or not, whatever that might mean.

———————

Dunno about Reconstruction, but that “whatever that means” parts sounds like Thomas Sowell’s “Black Redneck” theory: http://www.vdare.com/articles/tom-sowells-black-redneck-theory-ingenious-but-insufficient …

Sowell makes his case: http://capitalismmagazine.com/2005/07/black-rednecks-and-white-liberals-whos-a-redneck/

(But I’d agree with the “insufficient” description…)

Along that vein, Nast on “The Ignorant Vote-Honors Are Easy,” Harper’s Weekly,1876: http://cartoons.osu.edu/nast/images/ignorant_vote50.jpg

———————–

…I never thought in a million years that this would be a controversial post. Blackface caricature in support of neo-Confederacy…

————————

Is that “blackface,” or is it simply blacks being cartooned, eyes popping with rage? That cartooning utterly missing from the lifelessly noble example in “And Not this Man”?

Unfortunately, when attacking behavior or a side, how easy it is to rely on unpleasant stereotype: http://www.askart.com/AskART/images/interest/illustrators/3ThomasNast.jpg

Some “idealistic” Nast, this time in defense of Chinese immigrant laborers: http://cartoons.osu.edu/nast/images/The_Chinese_Question_50.jpg

More Nast, idealistic and not so, along with explanations for the shift in attitude:

————————-

Just as the Young America writers of the 1830s broke up over the issues of expansion and antislavery, so did the Civil War-Reconstruction Republican coalition come apart as new issues, and new attitudes, took center stage in American public life.

It was in the election of 1872 that the erosion of the wartime-postwar alliance became evident. In that year the Liberal Republican party emerged as an anti-Grant breakaway group, and New York Tribune editor Horace Greeley became the presidential candidate on both the Liberal Republican and Democratic tickets.

The appearance of the Liberal Republicans is usually attributed to a reaction by reformers to corruption in the Grant administration (though in fact the major revelations of corruption came during Grant’s second term). But by itself that is not enough to explain why Greeley, arguably the most influential voice of early antislavery Republicanism and the fight against the slave oligarchy of the South, would leave the party he had done so much to create and accept the nomination of a Democratic party tainted by pro-Southernism and Negrophobia. Nor does it explain why so many other editors, reformers, and Republican leaders in the fight against slavery and secession supported him…

Harper’s editor George W. Curtis was at the heart of the journalist-genteel reformer alliance that was the backbone of the Liberal Republican movement. Not surprisingly, tensions between Curtis and Nast mounted. Their differences were not only a matter of ideology, but of social-cultural milieux, and even of journalistic style. Nast observed of Curtis, “When he attacks a man with his pen it seems as if he were apologizing for the act. I try to hit the enemy between the eyes and knock him down.”…

[Nast] saw in Greeley and the Liberal Republicans a misguided naïveté, prone to manipulation by the Irish-Copperhead Democracy. (See figs. 23, 24, 25, 26, and 27.)

But Nast could not indefinitely resist the changes in American political culture that were moving intellectuals, cultural journalists, and political reformers away from the causes of the War and Reconstruction, and toward a political stance that dwelt on the dangers of political corruption, that feared strikes and radicalism, that was indifferent to African American civil rights. … [Emphasis added]

Nast continued to respond with some of his old fire to violence against Southern blacks, and to sympathize with the plight of Native Americans Indian and Chinese immigrants. (See figs. 31, and 32.) But these were insecurely held views, as the Civil War era commitment to equal American citizenship gave way to racist doubts. Indians on the warpath were to be met by a strengthened army, not by the reductions in military spending championed by ex-Copperhead Democrats. Racist stereotypy of blacks began to appear: comparable to those of the Irish—though in contrast with the presumably more highly civilized Chinese. (See figs. 33, 34, and 35.)

Nast came to echo reformers such as Curtis and Godkin not only in matters of race, but on economic and class issues. Financially secure himself, and solidly grounded in mid-nineteenth century Liberalism, he had little use for paper money inflation and less for radicalism; an attitude reinforced by events such as the 1887 Haymarket explosion in Chicago, when an anarchist bomb killed several policemen. (See figs. 36, 37, 38, and 39.)

By 1884 Thomas Nast’s political transformation was all but complete. Along with Curtis and Godkin, he supported Democratic candidate Grover Cleveland, who championed civil service reform, against machine Republican candidate James G. Blaine. Nast agreed that a politics of substance and meaning had been supplanted by the rule of the “practical politician,” bamboozling gullible black and Irish voters alike. (See fig. 40.)

—————————-

Emphasis added; more at http://cartoons.osu.edu/nast/keller_web.htm

Mike, it’s blackface iconography used as caricature. That is, the blacks here are meant to be real blacks, not people in blackface, just as McCay’s imp is meant to be a real black person, not someone in blackface — but the tradition of blackface iconography (or pre-blackface iconography probably in Nast’s case) is referenced or utilized to make black people look ridiculous and comical…and in Nast’s case monstrous.

Thanks for the background on Nast. As I said, his change of heart mirrored that of the nation as a whole…which makes it more depressing, not less, in a lot of ways. The post-Reconstruction abandonment of racial idealism is one of the most shameful and horrifying chapters in American history. Nast’s part in it is shameful as well…and I think it’s important to see it as shameful, and not just as a function of his point in history, mostly because his point in history is also still in a lot of ways ours, and we face some of those same choices today.

Thanks for this. I’m not sure the larger point, that Nast’s idealism gave way to racism is changed by the caption at all. If anything, the racist caricature is made worse by the contempt in which Nast apparently held poor whites.

Loewen (who I talk about a bit in the essay) is great in his discussion of the way the end of racial idealism post Reconstruction resulted in increased prejudice against basically everybody — definitely black people, but also Jews, white ethnics, Catholics…. The US just became a more racist society in every way. It’s a pretty thoroughly depressing tale.

” The US just became a more racist society in every way.”

Echoes of today? 120-odd years ago the new wave of immigrants no doubt triggered that xenophobia. And today, with whites on their way to becoming something of a minority….

Good job, Noah. There’s no better way to jangle a presumed consensus than to present the most clearly oppressive piece of culture imaginable and then wait for it to flush out the indignant hoarders of privilege.

Thanks Bert!

Steven, I don’t think that’s quite right, actually. The US becoming more racist wasn’t a reaction to immigration, I don’t think; it was a reaction to the North capitulating to the South’s rejection of Reconstruction. That is, it was a political shift, rather than a demographic shift causing a political shift.

The US now is way, way less racist than back then…and I think in concrete ways even less racist than a few years ago because of electing a black president. Not that we’ve attained utopia or anything, but it makes a difference. But…I do think that as long as we’re an imperial power, there’s a limit to how egalitarian we’re going to allow ourselves to become, unfortunately.

“The US now is way, way less racist than back then”

I was speaking off the top of my head. Let’s just say I don’t remember seeing empty chairs swinging from trees anytime until very recently. Without a doubt that small minority has been shouting louder these past few years.

There’s definitely a backlash…but I think it’s a backlash against the fact that the country has actually become less racist, at least in some ways.

I wrote about related issues here recently.

I do caution those who feel Nast went from a compassionate Liberal Republican and devolved to a Democratic-leaning racist. Comparing images side by side with several years in between is tempting to do. There is nothing wrong with comparing, for those comparisons are striking, but I urge those to look at the drawing in context of whatever news event may have occurred. I have been studying Nast for several years and am wrapping up a masters thesis on him. As an American of mostly Irish-Catholic heritage, his treatment of the Irish intrigued me. One big clarification, his move to support Grover Cleveland was not so much a conversion to the Democratic Party, but more for a complete disdain, mistrust and perhaps hatred of Blaine. Nast saw Blaine as a Republican who had turned on his principles, particularly where Chinese Exclusion was concerned. In my view, when any group acted stupidly, threw away their vote (as Blacks did to Democrats) and the Irish did for Tweed or to their church, Nast went on attack with his pen. He was not an inherent racist. He was the first to portray African Americans as normal. His antipathy with the Irish was directly related to their willingness to be manipulated by Tweed. Nast was born a Catholic, but he and his family did not believe in the infallability of the Roman Church. I was quite horrified to learn that most Irish Catholics were against abolition. Nast had issues with public monies supporting private -religious schools. When Nast moved from being a news illustrator to a editorial cartoonist, he did what master caricaturists do and continue to do, use set stereotypes and visual shorthand. (Think Richard Nixon ski-jump nose). There are pictures of normal white people – Columbia laying laurels on white policeman. They may be Irish. If they did nothing wrong, he did not caricaturize them.If they attacked Chinese, the Irish became apes and thugs. If he needed to make a quick visual point to highlight diversity, out would come the feathers for the Native Americans, the straw hat and big lips of an African American, the jaw-jutting Irish Simian, the pajama clad, queued-ponytail of the Chinese. To our sensibilities, these images are offensive – but Nast had reasons – usually political and newsworthy reasons – to go on the attack. Sometimes he just drew people and no one who knew who they were…but then, if it is that bland a situation – why do a cartoon caricature of it? He can’t be treated as an illustrator in this context. He is intentionally making it ugly – for shock value – to expose a hypocrisy – sometimes to throw the audiences thoughts right back at them – starkly. As if to say, “this is what you look like, sound like.” He lost favor with George Curtis. Curtis was pushing for a broader interest magazine. More illustrations – more romantic depictions of far way places. He marginalized Nast – his audience would often demand him back and his appearances in Harper’s ebbs and flows after the 1880s. Curtis wanted him less controversial. As far as the Irish today are concerned, they have successfully uproared loud enough to keep Nast out of the Hall of Fame. They point to the numerous mean and cruel drawings of the Irish and exclaim, “see?” But we have also failed as a people to acknowledge what our ancestors did that might have fueled these flames. There are at least two sides to every story and Nast’s images are only one side of them – it is important to understand his motivations is all I am suggesting.

I’m happy to look at context. I think it’s pretty dicey to argue that people somehow deserve to be seen as racial stereotypes though, no matter what they do, in large part because the point of racial stereotypes is that they are about…well, racial hallmarks, rather than individual actions.

And advocating for the solidification of white supremacy in the post-Civil-War South is pretty solidly evil in my book, whatever Nast’s reasons for it. That doesn’t mean that he was an evil man,necessarily, or that everything he did was evil — but in this particular case, I don’t see how he comes off as anything but noxious.

I don’t think he ever argued for white supremacy. If so, I’d like to see it.

If that cartoon is not an argument for white supremacy, I’m not sure what qualifies.

Utter nonsense. Nast is showing that given political power, blacks are every bit as capable of acting like jerks as whites are.

But then, no matter how egregious the behavior of some members of an “oppressed people” might be, it’s “not PC” to criticize them in any way whatsoever.

Did Nast always depict whites as noble and intelligent, blacks as brutes? Hardly.

Moreover, these particular politicians (thanks for the link and quote, Pepo Pérez) were described by Columbia in the cartoon as disgracing their race.

If blacks are seen as inferior goons, wouldn’t that behavior be typical, rather than a disgrace to their race?

Thus, Nast is clearly saying that the black race is far better than the enraged, tantrum-throwing politicos depicted.

Would an actual racist accuse black pimps, hookers, junkies, criminals of “disgracing their race”? No, he’d consider such behavior as natural as a chimp’s flinging poop.

As far as smearing Nast’s depiction of the arguing politicos as “blackface iconography used as caricature,” see authentic “blackface”:

http://www.criticalworld.net/criticalworld/files/2011/11/blackface.jpg

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/58/Minstrel_PosterBillyVanWare_edit.jpg/280px-Minstrel_PosterBillyVanWare_edit.jpg

http://www.retrosnapshots.com/media/catalog/product/cache/1/image/9df78eab33525d08d6e5fb8d27136e95/t/h/theatrical07.jpg

http://www.otrcat.com/z/blackface_AlJolson.png

http://4.bp.blogspot.com/-N0_MxQawAlU/UJLALPO93cI/AAAAAAAAB-A/Xt0eRw8zkXQ/s1600/IM002246.JPG

In Nast’s depiction, where are the exaggeratedly large and pale lips, the simple-mindedness?

If he’d drawn this guy — http://1.bp.blogspot.com/-TRFRsFDl-qg/UBnYYarFvJI/AAAAAAAAQo8/jVoLjs–buQ/s1600/Angry+Black+Man+%282%29.jpg

— would you call it “blackface iconography”?

Holy fuck. Mike. These kinds of assertions about black “failure” after Reconstruction were entirely ideological efforts to excuse relieving blacks of political power. This is ground zero for white supremacy and neo-confederate ideology. Images like this and arguments like this, abetted by full scale terrorism, is why we had 100 years of Jim Crow in this county.

The fact that he says he’s doing it for the good of the race is really less a noble gesture than an additional thumb in the eye when you’re drawing explicit racist caricatures that are being used at that very moment as an excuse to murder you and rob you of your rights.

I can’t believe I’m even having this argument. Where do you think the right wing fever swamp comes from, Mike? What do you think birtherism is about? This is a ton more straightforward than that, for pity’s sake.

He had the chance to experience for the first time, nine years of cohabitation and sharing of a new power structure. Behind his pen and paper, in his privileged “Yankee” town, he couldn’t comprehend what it meant to live with another subspecies and have conflict of genome.