The last issue of Ai Yazawa’s Nana in English is volume #21. The series stopped publishing in 2010, when Yazawa contracted an unknown illness. She hasn’t been able to work since.

Nana could not have picked a worse moment to come to an abrupt end. In Volume #20, Ren, the lead guitarist of Trapnest and the boyfriend of Nana Osaki, dies in a car crash. Volume #21 is an extended, painful depiction of grief, in all its overwhelming, banal detail. At this point in the series, after hundreds and hundreds of pages, we know all of Yazawa’s characters intimately, and their every characteristic and uncharacteristic action as they learn of their loss takes on an almost unbearable weight.

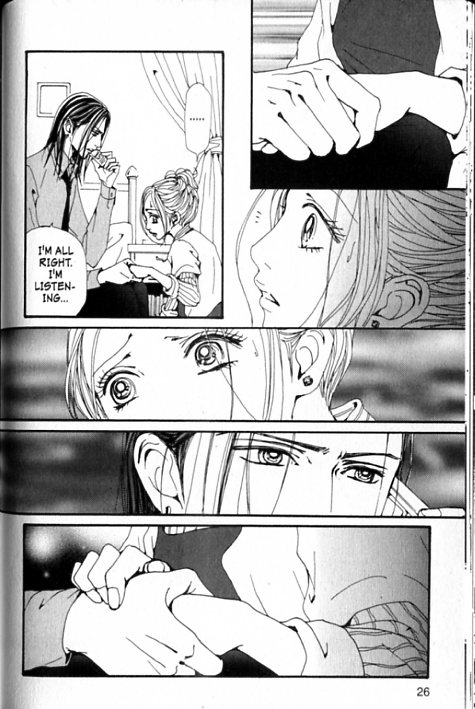

For example, it seems like the most natural thing in the world for a husband to grab his wife’s hand for support — except that distant, assholish, controlling Takumi hardly ever reaches out to anyone for anything. Nana Komatsu (or Hachi) knows her husband shouldn’t be behaving like this; she looks down at her hand as if she’s afraid it’s going to fall off. Ironically, soon after this, when Takumi views Ren’s body, he sees that the only part of Ren not badly damaged in the accident were his hands, which, a guitarist to the end, he protected during the crash. Ren’s fingers, carefully preserved, hold nothing, while Takumi and Hachi’s, unnaturally, hold, and are held by, his death. It’s not just that there’s space where there should be presence, but that there’s presence where there should be space. Ren can’t hold anything except those he leaves behind.

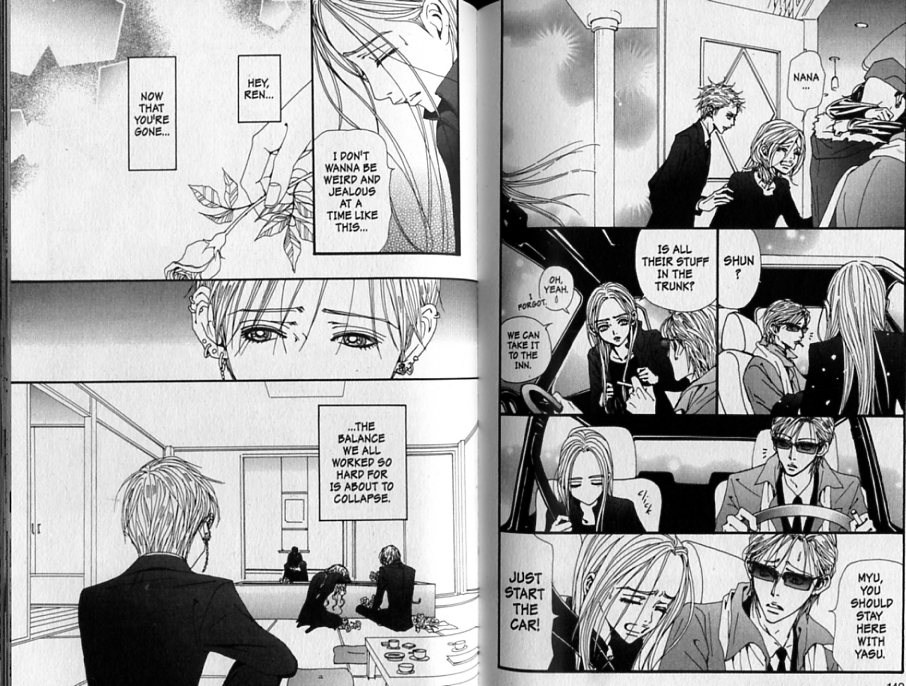

In another sequence, Yasu, Ren’s childhood friend who has an intense long term platonic relationship with Nana, goes to tell her that Ren has died. She’s a rockstar in her own right, and is on tour. Yasu has to fly out to get her and then they drive all night to get back home to see Ren’s body. When they come out of the car, Yasu carries Nana, who is draped over him helplessly. Yasu’s girlfriend, Myu, takes one look at them and flees:

Whereas Takumi’s reaction resonates because it’s not normal, Myu’s is touching because it is. Like Yasu, she’s level-headed and thoughtful. For him, that means being there for Nana when no one else will or can. For her, it means knowing when to get herself out of the way.

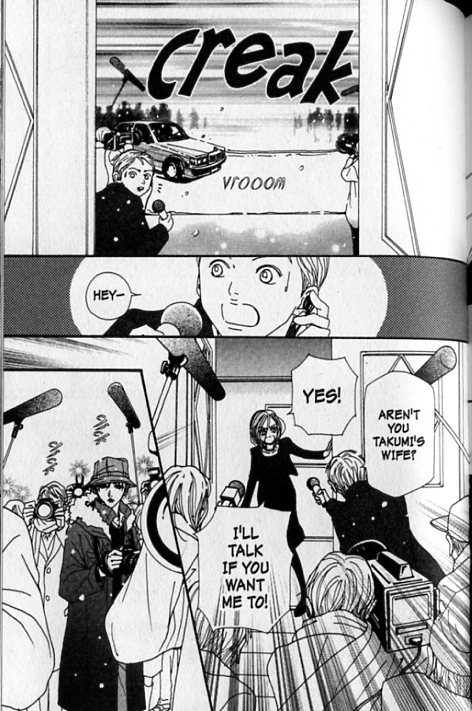

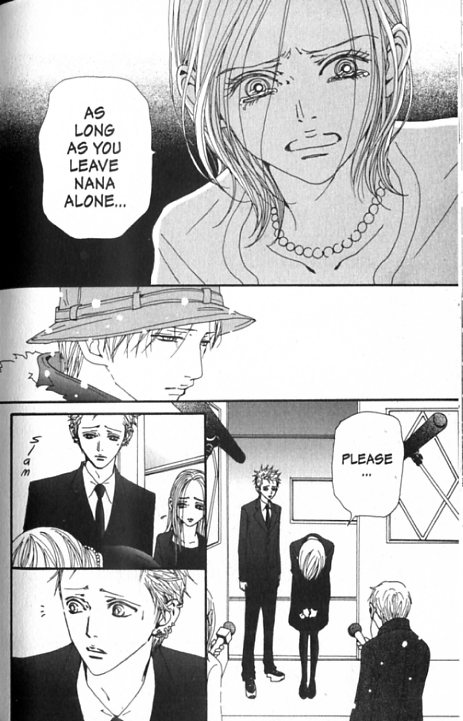

The scene that most affected me, though, occurs a couple pages earlier, when Nana’s car pulls up. Earlier in the series, Nana and Ren’s relationship became a gigantic tabloid news story; in fact, Ren’s car crash was caused in part because he was fleeing the papparazzi. Naturally, then, there’s a scrum of reporters waiting for Nana when she arrives, ready to ask her about Ren’s death. Hachi, Nana’s former roommate and one of her closest friends, intervenes:

Again, the sequence gets its power because we’ve known Hachi so long. She’s a strikingly hapless and needy airhead. She spends the series desperately glomming onto a series of men (and arguably women too) in an effort to get somebody else to provide the backbone and rational decision making functions that she so spectacularly lacks.

And yet, while Hachi is exasperating, she’s also very sympathetic…and this sequence helps to get at why. Over the course of the manga, Hachi develops a huge, somewhat ridiculous hero-worshipping crush on rock-star Nana. This seems like it should be another sign of Hachi’s puppyish infantilism — the nickname “Hachi” is in fact a dog’s name given to her by Nana. But instead of cementing her helplessness, Hachi’s clinging to Nana blurs into a kind of mothering, with Nana, estranged from her own mother, turning increasingly, semi-secretly, and desperately to her friend.

And so, in this sequence, when the worst ha happened, Hachi does what mothers often do, and sacrifices herself for her baby. It reminds me a little of my mother-in-law, who, like Hachi, is in many ways, infuriatingly flighty, and who, like Hachi, married too young. Yet, when my father-in-law (that man she married) was dying of brain cancer, she fed him and cleaned him and struggled tirelessly with a series of indifferent doctors and hospitals to get him the best possible care. Watching her was more than a little awe-inspiring.

Hachi here is awe-inspiring too…but there’s also something heart-breakingly futile about her attempted bargain with the reporters. Nobody takes her up on her interview offer…and indeed, Nana is swept out of the car too quickly for anyone to really get at her, it seems like. Hachi’s sacrifice ends up being superfluous; the story wouldn’t be changed at all without those two pages. Her love and her strength don’t really matter…just like, for all my mother-in-law’s efforts and care, her husband died just the same.

Life is filled with such blind alleys, of course, where the narratives sputter and stall and then go on; where the storyteller seems to have abandoned her work. Genre fiction, on the other hand, always know where it’s going — what’s the point of genre after all if you don’t have a blueprint? Nana, certainly, is as insistently artificial as any soap opera melodrama, packed with tell-tale and impossible coincidences. On the micro level, the two protagonists have the same name; on the macro level, everybody in the manga either becomes a rock star or marries one. That’s the inevitable teleology of fiction, not the stuttering uncertainty of fact.

Yet Nana‘s extended discursive format, and the way Yazawa privileges the characters and their emotions over the steady churn of events, often give the series a feeling of being weirdly aimless and fragile. In Nana #9, for example, Yazawa includes a short story purportedly about Naoki, Trapnest’s drummer. It starts with him dying his hair daringly blond, and then proclaiming to his parents, “It’s the real me, maman!”

That could be the start of a tale about discovering one’s true inner rebel rock star. But instead, Yazawa goes in the opposite direction; Naoki narrates, but what he narrates is almost entirely about other characters — or more precisely, about his misinterpretations of the other characters. He thinks Takumi and Yasu are gangsters, he misinterprets Takumi’s relationship with Reira (the Trapnest singer); he fails to recognize Yasu when the later changes his hair. The story isn’t about Naoki finding his real self, instead, it’s about how he fails to discover everyone else’s.

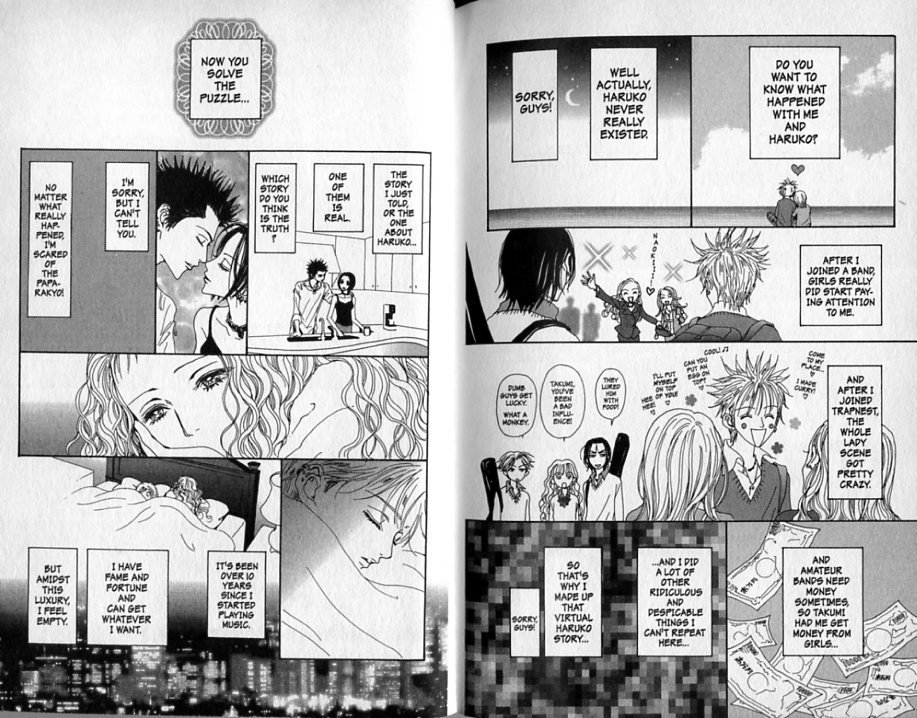

Finally, towards the end of the piece, we learn that there is a center to Naoki’s life — his relationship with his hometown sweetheart, Haruko.

Or, then again…

Haruko may be real, or she may not; her drawn image is either the the core of Naoki, or a meaningless surface. Moreoever, the meditation on truth and lies in the pages above is contrasted, not with pictures of Naoki, but with pictures of Nana and Ren. Haruko isn’t real, Naoki isn’t real…and of course, Nana and Ren aren’t real either. They’re just a dream. In the context of a serialized soap opera, this meta moment, where the headlong narrative collapses into itself, is unsettlingly disorienting. These people we know as friends are just visual illusions; line drawings on the top of nothing. The effect is not so much to knock us out of this story, as to knock us out of any story, including our own. Instead of images arranging themselves into a sequence, they seem to hang still, unorganized bits and pieces that refuse to make a whole. Genre falls apart, as ungraspable as life, or as death.

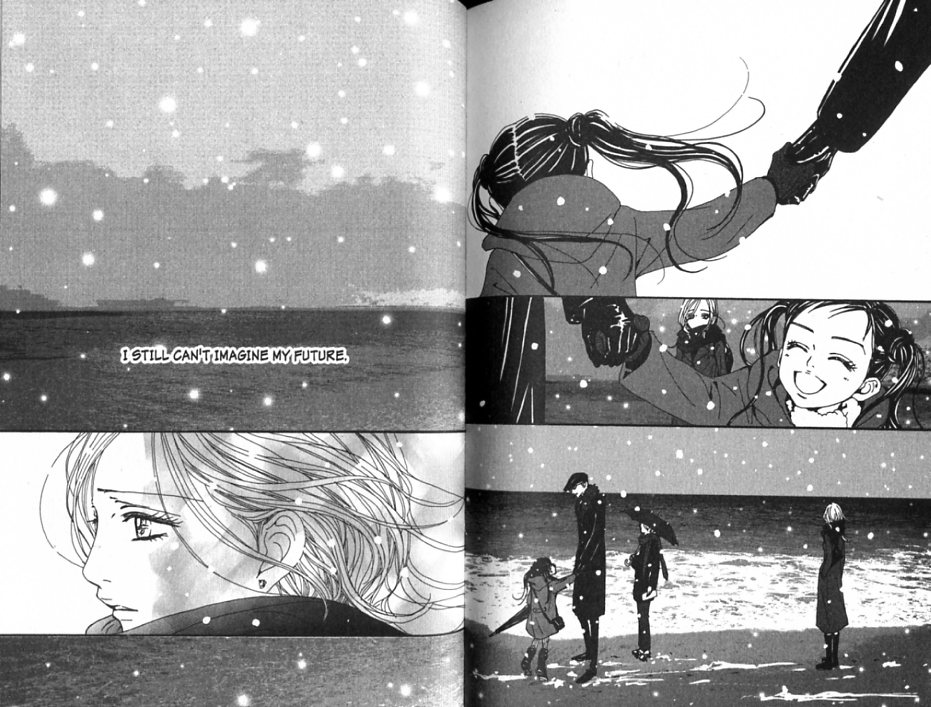

There’s a similar effect in the latter part of the series, when Yazawa begins to let us see glimpses into the future of her characters. But these futures are less a terminus, giving finality and shape to the whole, than a way to extend and double the narrative’s irresolution. Nana-to-come has run away and is living incognito…but perhaps she’ll return. Takumi-to-come and Hachi-to-come are estranged. But that’s not the end of their relationship. It’s simply another stage in it, as subject to change and vacillation as the past. There is no happily ever after, not because there isn’t a happily, but because there’s no ever. The characters keep falling out of the genre narrative, or else the genre narrative falls from around them, like snow dissolving. “After your death, the future we all hoped for was wiped clean,” future Hachi says to the long- passed Ren. “I still can’t imagine my future. I can’t begin again unless Nana is with me.” But while she’s saying that, the future goes on; her daughter plays with Yasu, the waves go in and out, the snow comes down. The plot is gone, but she’s still there, lamenting the fact that death is an end, and also lamenting the fact that it’s not.

Those are the last pages in Nana #21. The series hangs there still, waiting for Yazawa to come back, or never to come back, just as Hachi is waiting for Nana. We’re stuck with grief and a future that won’t tell us what it means. Maybe that’s why sometimes the worst comic book is the one that was never written — the page that you can’t turn, and can’t stop turning.

__________

Click here for the Anniversary Index of Hate.

Great post, Noah.

It’s funny, in the huge Richard Brautigan bio I read recently, he spent a lot of time in Tokyo in the 70s and he was a little obsessed with the statue of Hachi the dog that Nana is nicknamed after. It was weird finding that story/name in such a different context than the Nana manga.

I don’t know how long it took me to figure out what Hachi’s nickname meant. Yes, I am a gaijin, and slow of mind….

Don’t they explain it in the comic?

More or less. Thus my characterization of myself as “slow of mind.”

I haven’t read this far in the series, so I’m avoiding reading this post, but if you want more weirdness, there’s also an American movie about the Hachi story starring Richard Gere; I haven’t seen it, but I think it imports the story whole to the US without acknowledging its Japanese origin. Gotta love that Americentrism!

Bah! This isn’t hate, it’s unmitigated love, love, love…Actually, from my slightly more than limited experience with romantic TV shows/manga/novels, it’s the ideal ending to such storylines.

Well, I don’t say that it isn’t.

And hate and love are hard to separate.

Oh Noah, the never-drawn Issue 22 may be the best comic of all time — so long as it remains undrawn.

Consider so many unfinished works. Dickens’ “The Mystery of Edwin Drood”, left incomplete by the author’s death, has surely caused more pleasure by tantalising readers into creative speculation, than it would have by offering a standard mystery resolution.

And Schubert’s Symphony #8 — the so-called ‘Unfinished Symphony’–

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m33pGwho4-I

— could the actual missing movements measure up to the listener’s feverish imaginations?

Ah, the beauty of the incomplete…something largely uncodified in aesthetics, apart from in Japan…but instinctively grasped by so many artists, such as the sculptor Rodin:

http://www.google.fr/imgres?q=Rodin+unfinished&num=10&hl=fr&biw=1280&bih=933&tbm=isch&tbnid=YdoJvhnkkePhYM:&imgrefurl=http://portraitcameos.com/rodin-daniad-sculpture/&docid=LuzEi4yBOGJfhM&imgurl=http://gemportraits.wpengine.netdna-cdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/Rodin-sculpture-Daniad-1.jpg&w=940&h=600&ei=fR5vUJeBNuWd0QXdwIGgDQ&zoom=1&iact=hc&vpx=871&vpy=273&dur=88&hovh=179&hovw=281&tx=143&ty=106&sig=103709501995750793707&page=1&tbnh=140&tbnw=195&start=0&ndsp=35&ved=1t:429,r:5,s:0,i:86

Have you read Fitzerald’s last, unfinished novel– ‘The Last Tycoon’? And the notes detailing his execrable plot for the end, replete with hitmen and plane crashes? We are left with fragments more satisfying than the putative finished novel.

To get back to comics, Jack Kirby’s ‘Fourth World’ is all the more alluring for being cut off in its prime.

So, Noah, let us revel in, rather than mourn, Nana’s incompleteness. For how could the ideal Nana#22 measure up to the ideal Nana#22 we have spun in our minds?

Again…you’re not arguing against the piece there, Alex.

Dirk Deppey just told me on twitter that there are a few more chapters completed in Japan but not translated, apparently…so perhaps I will get to see those at some point….

Desist, Noah. They could never compete with your imagined conclusion.

Nah, I’ll read em if I can fine em. I trust Yazawa. I’ve got 21 volumes, and the last one is just about the best. Even if the next one isn’t quite as good, I have faith that it’ll be worthwhile.

Even if I don’t agree with your assessment of Hachi as “a strikingly hapless and needy airhead” (probably due at least in part to the intensity with which I identify with her personally–it’s a thing) I really enjoyed your insights here, both about her and about the series in general.

There is no happily ever after, not because there isn’t a happily, but because there’s no ever. The characters keep falling out of the genre narrative, or else the genre narrative falls from around them, like snow dissolving. “After your death, the future we all hoped for was wiped clean,” future Hachi says to the long- passed Ren. “I still can’t imagine my future. I can’t begin again unless Nana is with me.” But while she’s saying that, the future goes on; her daughter plays with Yasu, the waves go in and out, the snow comes down. The plot is gone, but she’s still there, lamenting the fact that death is an end, and also lamenting the fact that it’s not.

This was my favorite part. As a fan of the genre, I’m as susceptible to the appeal of “happily ever after” as anyone (and even just the nice, clean “ever” most fiction provides, happily or not), but the older I get, the more I appreciate the rare instances in which an author refuses to give that to me. Reality may be less thrilling and it’s certainly much less neat, but it’s ultimately more beautiful.

Glad you liked it!

I don’t think Hachi is *only* hapless and airheaded…but clearly it’s part of who she is. She can’t even hold down a menial secretarial job because she’s too irresponsible — and all she thinks about (at the beginning especially) is boys, boys, boys and also boys….

Oh, and just to be clear…I quite like Hachi, even if some of her choices are pretty frustrating.

And to be clear, as much as I love/identify with Hachi, I often find her frustrating as well. Actually, some of the ways in which I identify with her most are also the most frustrating parts. Nothing like recognizing your own flaws in somebody else, right? Heh.

This is the way the Hate ends

Not with a bang but a whimper

It was sad to find out that the manga ended like this I couldn’t believe it. I spent an hour looking online hopeing to find out there was gunna be another volume, but sadly there wasn’t any clues leading to that. This possibly final volume of Nana was great but at the very same time dissapointing. I’ve read volume 21 three times a each time I couldn’t stop myself from crying. This was a great emotional series and all the charecters personality was so great and noticable I felt like they were real. Yazawa is a great author and I hope that Yazawa tries to continue with the story somehow but if not i’m happy either way.

Hey Mary. There are a few more chapters I’ve learned, though they haven’t been published in the US, unfortunately.

That last volume is an emotional wringer, there’s no doubt.

This is big news on ai yazawa!

http://www.animenewsnetwork.com/news/2013-01-25/nana-yazawa-draws-new-junko-room-chapter

Thanks for the link! That’s heartening news….

Pingback: Manga Bookshelf | Hope for NANA?

So much of the power of Nana is not just Yazawa’s great storytelling but her visuals as well, especially volume 21’s. The image that sticks out to me most is when Hachi, Shin and the others are sitting in a dark room, after obviously crying for hours. That panel makes me cry more than any other scene. I just hope Yazawa brings this series to the end it deserves!

http://shojocorner.wordpress.com/2011/11/12/nana-visual-tragedy/

Not trying to be a wet blanket about the good news but, with so many questions left unanswered, why did it have to be Junko’s room? I always found that woman surly and pompous.

Anyway, this was a fantastic read! Reading over random blogs about Nana has been my only consolation since I read the last chapter, so thank you. I really enjoyed this!

You don’t like Junko?! I loved her! She may be my favorite character even; the take-no-bullshit surliness really appeals to me.

Which…now that I am thinking about it, perhaps explains why I am so fond of my wife. But maybe that’s TMI…..

ha! I’m sure your wife is a lovely woman, I think I’m just bitter because she took up Shouji’s defense when Nana was having her breakdown. A bizarre defense at that. Since when does making new friends mean you are selfish and deserve to be cheated on? Particularly when you only became more independent at the cheater’s insistence?

Bitch move Junko, bitch move.

Hmm…that’s a fair enough point. I need to reread that bit….

Please does anybody knows if in the meanwhile their is a Nana volume 22? I’m living in Belgium helplessly waiting for the story to continue. Even online site for me is oke.

Already thanks a lot for those who answer this reaction.

X

Nandi

I don’t believe it’s come out (it may well never come out, alas.)

I am two years too late to read this but it just shows how much i still haven’t gotten over NANA…i loved ur analysis. i also happen to believe Hachi is hapless, but she’s naiive in the sense that makes me feel sorry for her, not despise her. i believe this is because Yazawa draws a very meticulous rounded picture of her, like you said it’s not the only thing we identify her by. Hachi comes from an air-headed family that has not had to want for anything, this doesn’t excuse her naivety, same as Takumi’s abusive father doesn’t excuse his coldness and actions, it just puts things into perspective, makes us understand a little bit why someone like Takumi even married Hachi, and accept Hachi a little bit when she is trying to become a better person but is stuck with her naiive personality to find solutions for the mess she is in…and to bring someone else into perspective, if we consider Reira, another flighty girl, she’s actually very pathetic as well that you can’t help not to be sorry for her, how Takumi manipulates her (or is possessive of her like his own personal gem anyhow u wanna see it), and imprisones her: like conisder this, the first time we see Reira talking, she knocks on Ren’s door, she has a small scarf over her neck and she invites Ren to come play with them, Ren refuses but asks her if she’s okay since he felt her voice was coarse, Reira cheerfully replies that there are 16 more shows to go and “let’s do our best”. When i watched this scene for the second time, i realised how much Yazawa was bringing out from Reira’s loneliness and enslavement with just this small introduction. So yes, Reira is annoying and pathetic, and does all the wrong things at the wrong times, but with Yazawa’s work of her, hate is never something i associate with her…

Partciularly in NANA i don’t believe the purpose ever was to love or hate a character, it is to know them, like after a while of being married it becomes less about that original love feeling and more about knowing the person you’re spending your life with…maybe it’s a little extreme to compare marriage to reading NANA but the point is, I can talk a lot about how the characters are deeply twisted, how i think Nana O. and Ren’s relationship was not the “soulmate” lovey-dovey type but a very possessive unhealthy one, i can disintegrate each character, i can read/watch a scene with them all sitting together and each one saying exactly what is expected from that character…this picture Yazawa drew of them, it was so concrete, soap opera melodramatic or not, it has brought something out to a brilliant light and i don’t think one who has been witness to it can ever forget it, like a friend who was a part of your life that you carry on.

That was beautiful Haruka! You nailed it!

I love this manga very much. I have been reading it since 08. And even thinking about this manga brings me back so many nostalgia. I love the vivid story telling it brings and the pictures. It clutches your soul and makes you yearn for the characters and feel for them. I don’t think anyone who reads this manga can ever forget it either. And I hope the author will continue with the manga. It’s a beautiful work.

I loved this piece. You really hit all the nails on the head, including some I didn’t see before, haha. Did you ever get a chance to read the chapters allegedly released in Japan?

I haven’t! I’m a little afraid to, and so haven’t done so, though I do have them….

I know what you mean! I’m not sure I want to know how it ends either. :/ Would you mind sharing them with me, if possible? Or letting me know how I could get them? I would like to have the option of reading them, but I don’t want to ask too much. Google has been no help in the search, unfortunately.

This post is so, so old, but it really got to what I love about this series:

“Nana, certainly, is as insistently artificial as any soap opera melodrama, packed with tell-tale and impossible coincidences. On the micro level, the two protagonists have the same name; on the macro level, everybody in the manga either becomes a rock star or marries one. That’s the inevitable teleology of fiction, not the stuttering uncertainty of fact.

Yet Nana‘s extended discursive format, and the way Yazawa privileges the characters and their emotions over the steady churn of events, often give the series a feeling of being weirdly aimless and fragile.”

Perfectly articulated.

Did anyone ever find new chapters? I need closure.

I REALLY HOPE SHE FINISHES THE REST OF THE STORY