There were a lot of great story arcs written during the Silver Age of Comics, which most comics historians agree spanned the years 1956-1970. But the best one, in my opinion, “If This Be My Destiny,” was published as a three-part story in “Amazing Spider-Man” issues 31-33, cover-dated December 1965 through February 1966.

But before we can analyze exactly why the story was so special, we first need to identify who the key player was in its creation, layout, pacing and overall story.

Stan Lee was attributed as the “writer” of the story in the credits, but he, as I discuss below, had nothing to do with the story arc’s creation. For while he wrote the dialogue after the pages were laid out and drawn, he did none of the plotting, and had zero input on the pacing, basic character interaction, mood, and story direction. All of that was done by artist Steve Ditko.

The “Marvel Method” of creating comics during this period was peculiar in that regards, especially for Lee’s top bullpen artists Ditko and Jack Kirby. When the process was first implemented by Lee in the early 1960s – ostensibly to save him the time of writing a full-blown script – he and the artist of a particular comic book would have a story conference, work out a plot, and the artist would go home and draw out the entire issue. The finished pages would then be given to Lee, who proceeded to add the dialogue.

But by the mid-1960s, Kirby and Ditko were so good at creating and plotting stories that Lee himself admitted in a number of interviews that he often had little or no input for story arcs. In fact, he often would have no idea what the story for a particular issue was going to be about until after the pages were delivered by the artist.

Lee himself details this Marvel Method process in an unusually candid interview he did for “Castle of Frankenstein” #12 (1968), a magazine that covered popular culture from that era:

“Some artists, of course, need a more detailed plot than others. Some artists, such as Jack Kirby, need no plot at all. I mean I’ll just say to Jack, ‘Let’s make the next villain be Dr. Doom’… or I may not even say that. He may tell me. And then he goes home and does it. He’s good at plots. I’m sure he’s a thousand times better than I. He just about makes up the plots for these stories. All I do is a little editing… I may tell him he’s gone too far in one direction or another. Of course, occasionally I’ll give him a plot, but we’re practically both the writers on the things.”

This was also true with Ditko and his early Marvel Method process on “Amazing Spider-Man.” He and Lee would have a story discussion, after which Ditko would leave, pencil out the story and then, inside the panels, write in a “panel script” (suggested dialogue and narration). He would then bring the pages back to Lee and they’d discuss the story from start to finish. Ditko would annotate any changes outside of the panels, and then he’d leave the penciled pages with Lee. Lee would then write in the final dialogue and the book would be lettered. Ditko then picked up the lettered pages, and made any of the annotated changes during the inking process.

But Lee really had no long-term vision for Spider-Man. He never thought about what he would do with the characters from one issue to the next. He’d just say, “Let’s make Attuma the villain,” and Ditko would have to talk him out of it. The glue that really held the Spider-Man direction and continuity together in those early days of the character was Ditko.

Over time, Ditko received more and more story autonomy and character development latitude that by about issue #18, he was doing the sole plotting chores with no input from Lee. But it took time for Lee to give Ditko what was then unprecedented plotting credit, beginning with “Amazing Spider-Man” #26 (July 1965), and ending with Ditko’s last issue, #38 (July 1966).

As with many aspects of those murky creative days at Marvel, Ditko’s credits raise questions. For example, why did Lee agree to give Ditko plotting credit, but not Kirby, whose “Fantastic Four” and “Thor” plotting autonomy was apparently quite similar? And why did Lee, when he finally did start giving artist and plotting credit to Ditko, suddenly, after one issue, expand his own credits from “writer” (his standard credit line for the first 26 issues of “Amazing Spider-Man”) to both “editor and writer”?

Around the time Ditko began receiving plotting credit, a rift between the two arose and, according to several Marvel staffers, was so acute, Lee would not speak to Ditko. It was during this year-long communication blackout period that Ditko wrote his Spider-Man magnum opus, “If This Be My Destiny.”

Additional evidence that Lee had no story input during this period can be found in “Amazing Spider-Man” #30, which set the stage for Ditko’s historic three-issue story arc. In that issue, the villain is a thief named The Cat, but Ditko also introduced, in two different parts of the story, henchmen for The Master Planner – the surprise villain for the “Destiny” story arc that was to start in issue #31. Yet because communication between Lee and Ditko had ceased, Lee had no idea who the costumed criminals were and misidentified them as The Cat’s henchmen – which, upon close examination of the story, makes no sense. It’s not until the next issue that the error becomes obvious to Lee and he gets a better grasp of Ditko’s storyline.

So, now that we have a better understanding about who created what for this historic story arc, exactly what is it that makes Ditko’s “Destiny” so great from both a literary and artistic standpoint?

How does one go about measuring greatness? After all, there are no established standards for greatness in comics, or, for that matter, the two creative disciplines that are merged to create them: art and literature.

Some argue that great art or literature is timeless, and that it appeals to our emotions in a compelling and riveting way. Others argue that it is something that breaks new ground.

Ditko’s three-issue story arc easily accomplishes all three, and a lot more.

We can glimpse Ditko’s personal, objective views about what constitutes art from his recorded statements for the 1989 video, “Masters of Comic Book Art.” Ditko said that based on Aristotle’s Law of Identity, “Art is philosophically more important than history. History tells how men did act; art shows how men could, and should act. Art creates a model – an ideal man as a measuring standard. Without a measuring standard, nothing can be identified or judged.”

It’s clear to me that Ditko, through his stories and art in “Amazing Spider-Man,” was striving to do just that: mold Peter Parker/Spider-Man into a positive heroic model.

Throughout his career, Ditko has always been a creative, experimental, thinking-man’s innovator. It was evident in his costume designs, character portrayals, settings, lighting, poses, choreography, etc. – literally every aspect of the comic book creative process. For example, no one before or since has created anything like Ditko’s multi-dimensional worlds for his Doctor Strange character. And his creative depictions of Spider-Man’s costume, devices, movement through space, and overall look set the standard for every single Spider-Man artist who has followed. I’ve been a fan of his work for 45 years, and to this day, I still marvel at how Ditko was able to take the totally fantastic and make it seem like it could actually be real.

Ditko was innovative in other ways as well. Unlike many of his contemporaries back then, Ditko had an eye on continuity, and started meticulously planning story arcs and sub-plots many months or even years in advance. Such was the case with his slow and methodical development of the Green Goblin‘s secret identity over a multi-year period, and his tantalizingly slow introduction of Mary Jane.

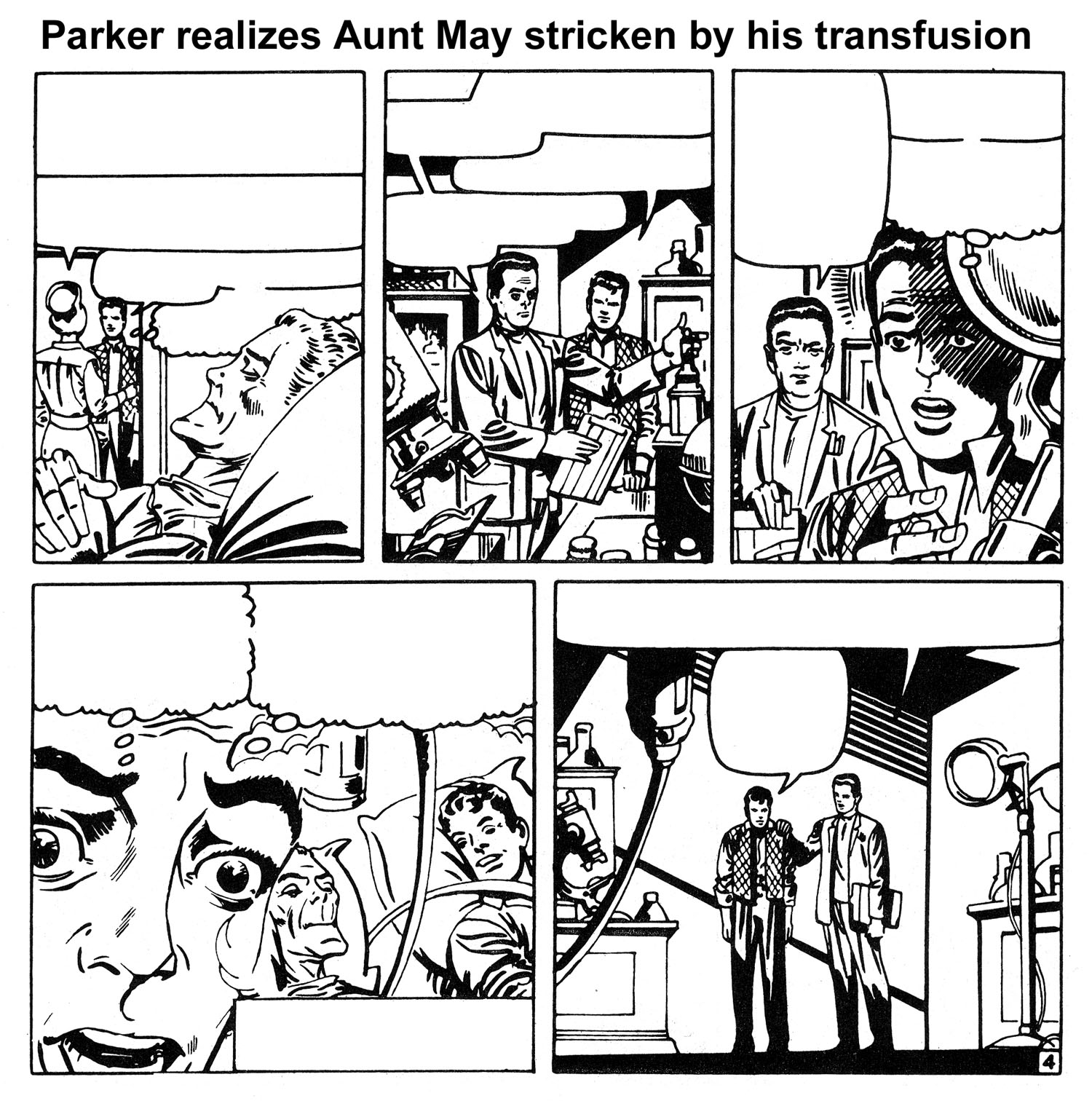

Ditko’s development of his “Destiny” story arc in “Amazing Spider-Man” #31-33 was no different. Ditko planted the initial seed for the arc way back in issue #10, when Peter Parker provided blood during a transfusion of his seriously ill Aunt May. As regular readers eventually found out, Parker’s selfless act of kindness turned out to be a ticking time bomb for his frail aunt, who began suffering ominous fainting spells in issue #29, and again in issue #30.

As I mentioned above, the mature, heroic side of Peter Parker and Spider-Man had been building for many months before the “Destiny” story arc kicked in – a steady drumbeat that would soon reach a deafening crescendo. At the same time, Parker was enduring important emotional lows and highs. For example, his long relationship with Betty Brant had been pulled wire taut in the months preceding “Destiny,” and was at the breaking point. Likewise, Parker graduated high school in issue #28, and was about to go off to college and enter what he hoped was a new and exciting chapter of his life. But despite his emotional roller-coaster rides, it was clear to the regular reader that Parker was growing more mature, determined and focused both as a normal person and as Spider-Man. He was no longer the silent doormat for his boss, J. Jonah Jameson, his high school nemesis Flash Thompson, or any other negative influence in his life.

It was at this convergence of events where “Destiny” began, and the reader soon found out just how mature, determined and focused Parker and his alter ego would be under the most harrowing of circumstances – circumstances that would have the highest emotional stakes imaginable for the character.

As the three-issue story arc opened with issue #31, the stage is set for what’s to come when Spider-Man stumbles across the Master Planner’s men fleeing, via helicopter, a location where they have just stolen some radioactive atomic devices. A battle ensues, but they escape. It is during this escape that the Master Planner’s underwater refuge – a key location later in the story – is revealed.

The scene shifts to Peter Parker’s home, where he waves goodbye to his Aunt May before heading off to his first day of college. The reader can see that she is gravely ill, but she’s doing her utmost to hide it from her nephew so he doesn’t worry. When Peter returns later that day, she can hide it no longer and collapses in his arms. Her illness is so serious, their family doctor admits her to a hospital. Peter is by her side until she falls asleep, and heads for home. Here the emotional roller-coaster starts its journey again as Peter tries to juggle college, lack of sleep, mounting bills, and Aunt May’s illness all at the same time. But Aunt May’s illness overshadows everything else and his new classmates find him aloof and distant.

As his money pressures mount, Peter changes to Spider-Man so he can look for news photo opportunities around the city – as taking news photos for “The Daily Bugle” is his only source of income. He gets a tip that a robbery will be taking place at the docks that evening, and when he arrives, he once more finds the Master Planner’s men attempting to steal a ship’s radiation-related cargo. Another battle ensues, and they escape again – this time into the water using scuba gear. As the issue comes to a close, an unseen Master Planner, in his underwater lair, mulls how Spider-Man is thwarting his attempt to use radiation secrets for nefarious purpose. But the final three panels are far more ominous: the doctors caring for Aunt May have finished their tests, and conclude that she is dying.

Issue #32, “Man on a Rampage,” opens in the Master Planner’s underwater hideout, and we quickly find out that he is actually none other than Dr. Octopus, one of Spider-Man’s most dangerous foes. The scene then shifts to Peter, whose relationship and money problems keep mounting. But things get even worse when he visits the hospital and the physician attending to Aunt May informs him that her terminal illness is being caused by an unknown source of radioactivity in her blood. Peter immediately realizes that the radioactivity must have come from his contaminated donor blood which Aunt May received during a transfusion many months earlier for a different illness.

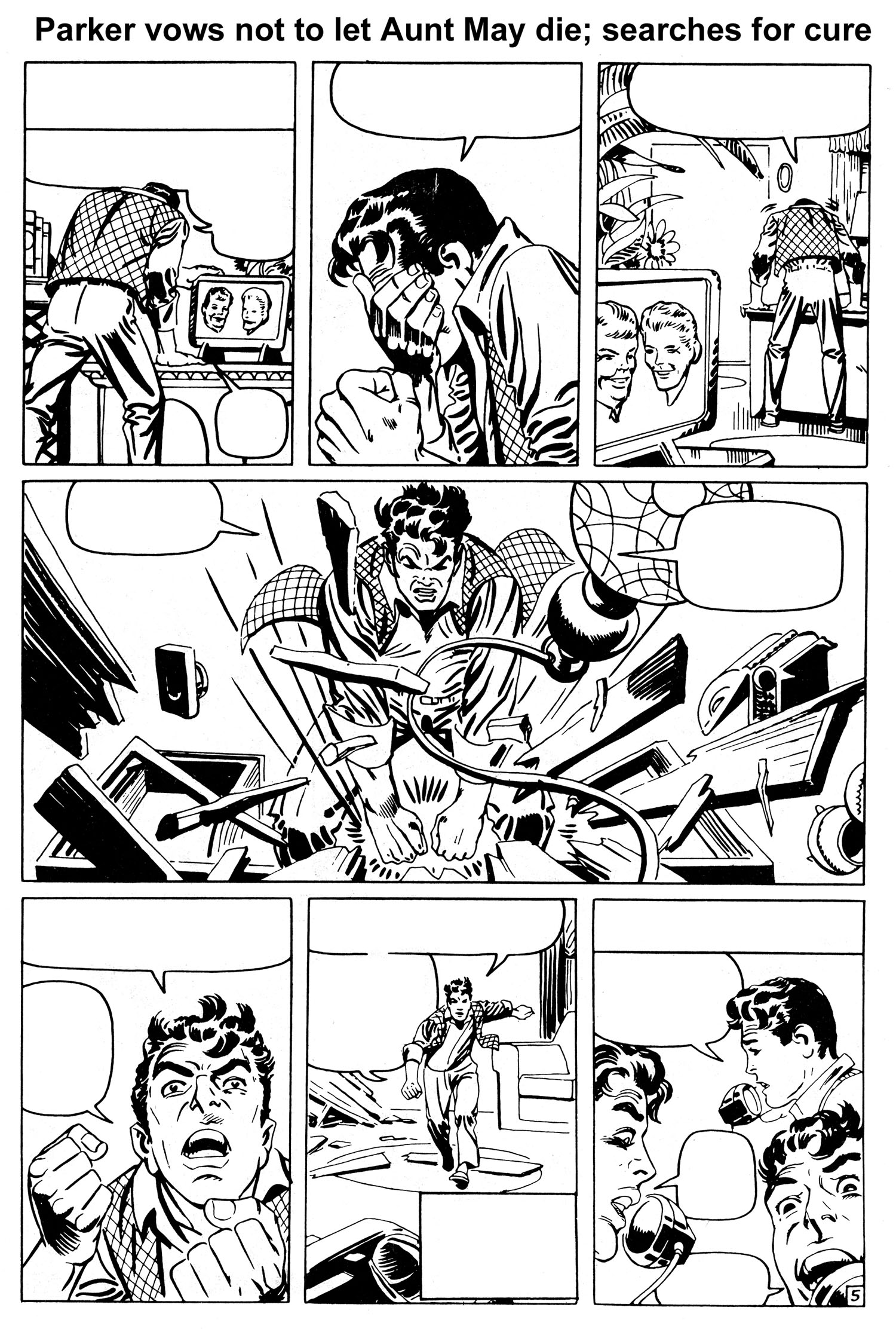

And while the radioactivity is harmless to him, it is having a devastating effect on Aunt May. So not only was young Parker responsible for the death of his Uncle Ben when he first became Spider-Man, he may soon be responsible for the death of Aunt May. This emotional realization is perfectly portrayed by Ditko, along with Peter’s vow that he will not fail at saving a loved one again.

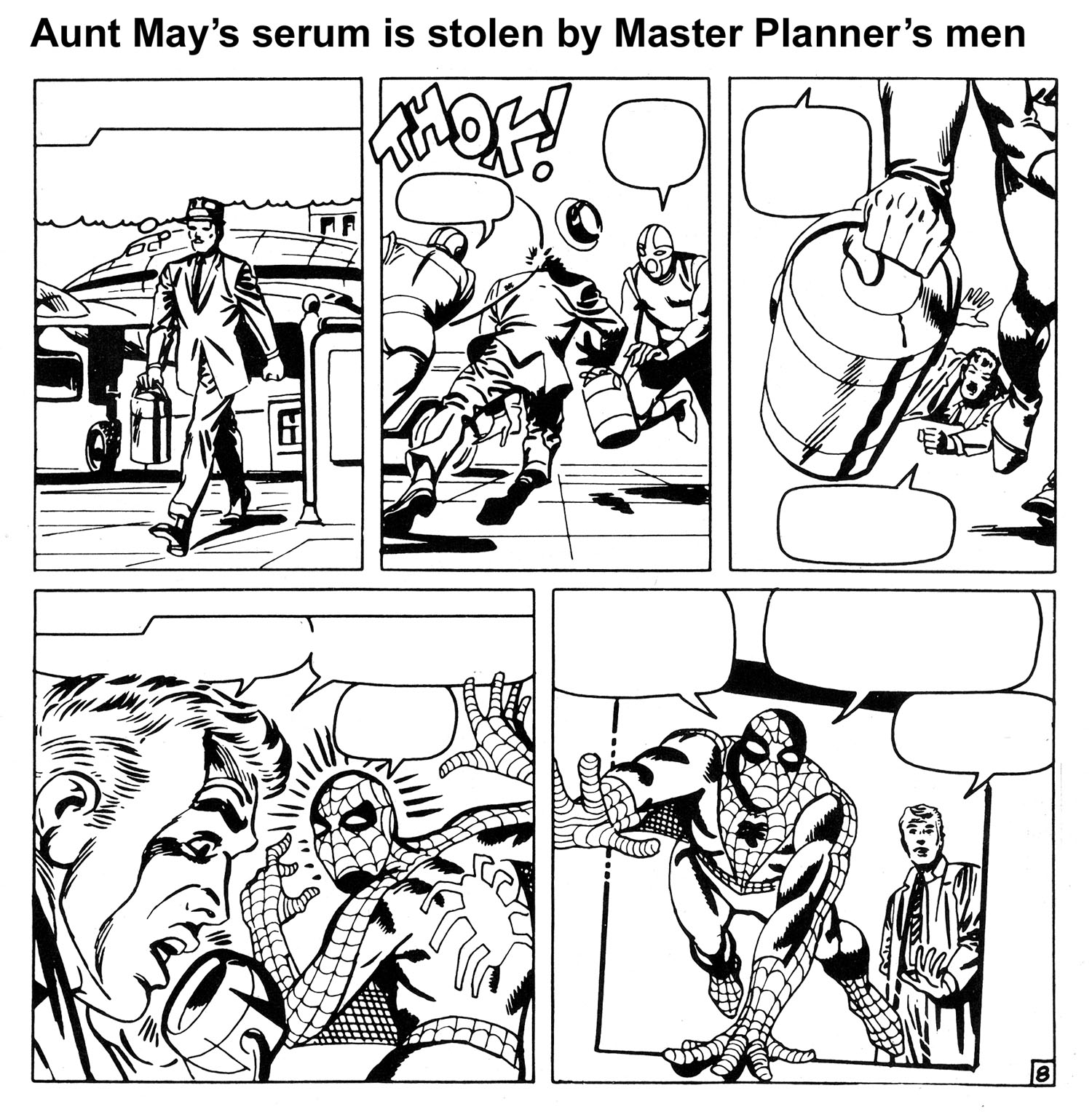

Parker then gets an idea. He tracks down Dr. Curtis Connors (aka The Lizard) – a blood specialist who he hasn’t seen since issue #6 – and, as Spider-Man, gives him a stolen vial of Aunt May’s blood, and begs him to see if he can discover a cure for his “friend.” Connors agrees and after some tests says that an experimental serum called ISO-36 might help – but it will cost money. Parker leaves, hocks all of his personal laboratory equipment, gets the money, and returns to Connors’ lab as Spider-Man. While they wait for every available bit of the rare serum to be express-delivered from across the country, Parker, a budding scientist in his own right, helps Connors with some preliminary lab research. Suddenly, Connors gets a phone call informing him that the ISO-36 was stolen by the Master Planner’s henchmen, and Spider-Man explodes into action.

In an effort to find the precious stolen serum, Spider-Man literally does go on a rampage, snatching up criminals and stoolpigeons, smashing down doors and rooting through every underworld nook and cranny across the city for any possible leads. As the clock ticks, we see Aunt May slip into a coma, Dr. Connors patiently waiting, and a desperate Spider-Man becoming more and more frantic.

Suddenly, after swinging into a blind alley, his Spider-Sense points him to a hidden trapdoor leading to the underground tunnel entrance for the Master Planner’s underwater hideout. Battling through dozens of henchmen, he slips through a sliding doorway into the tunnel. Alerted by one of his men that Spider-Man is searching for the stolen ISO-36, Dr. Octopus decides to use it as bait so he can kill Spider-Man, once and for all.

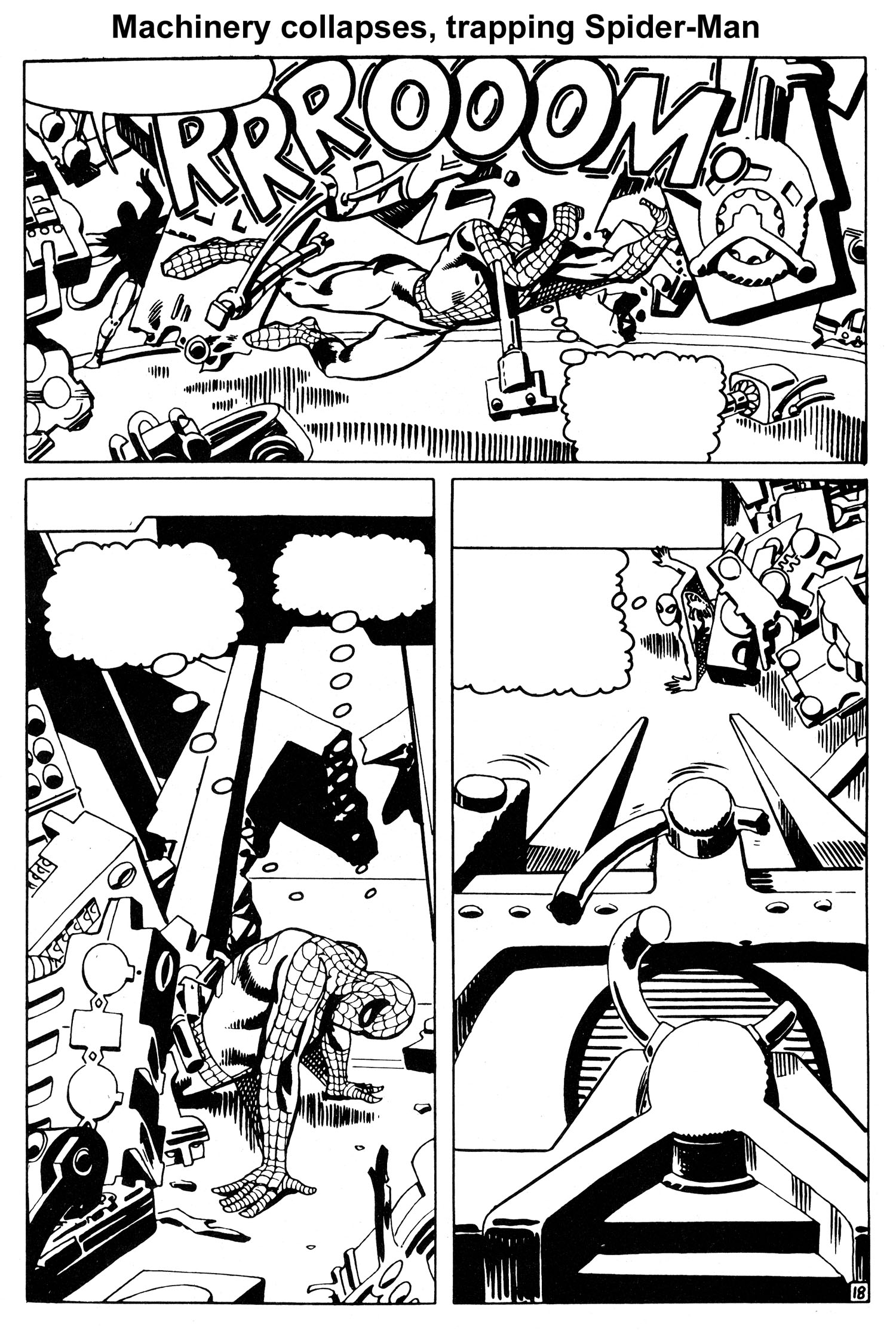

He places the serum in the middle of the cavernous domed main room of his underwater lair, and waits. Spider-Man enters, and despite a last-second warning by his Spider-Sense, the trap is sprung and a raging battle ensues. But Dr. Octopus soon finds out something is different this time, as Spider-Man is fighting like a man possessed. Startled, Dr. Octopus quickly shifts from offense to defense, and within minutes is no longer fighting, but trying to find a way to escape the madman he is facing. A main support beam is shattered during the fight, and as the machinery inside the dome begins collapsing, Dr. Octopus slips away. But Spider-Man is trapped.

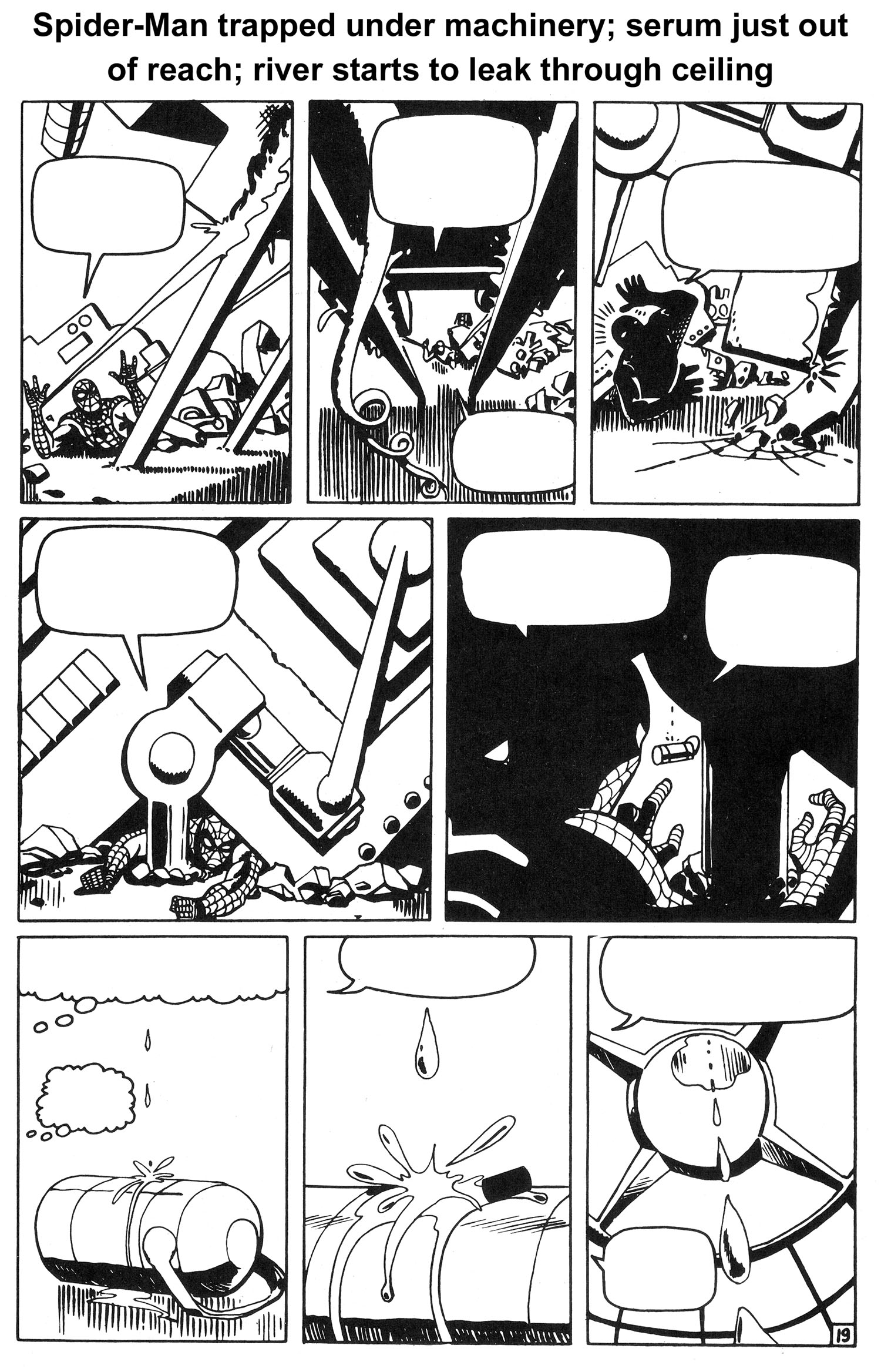

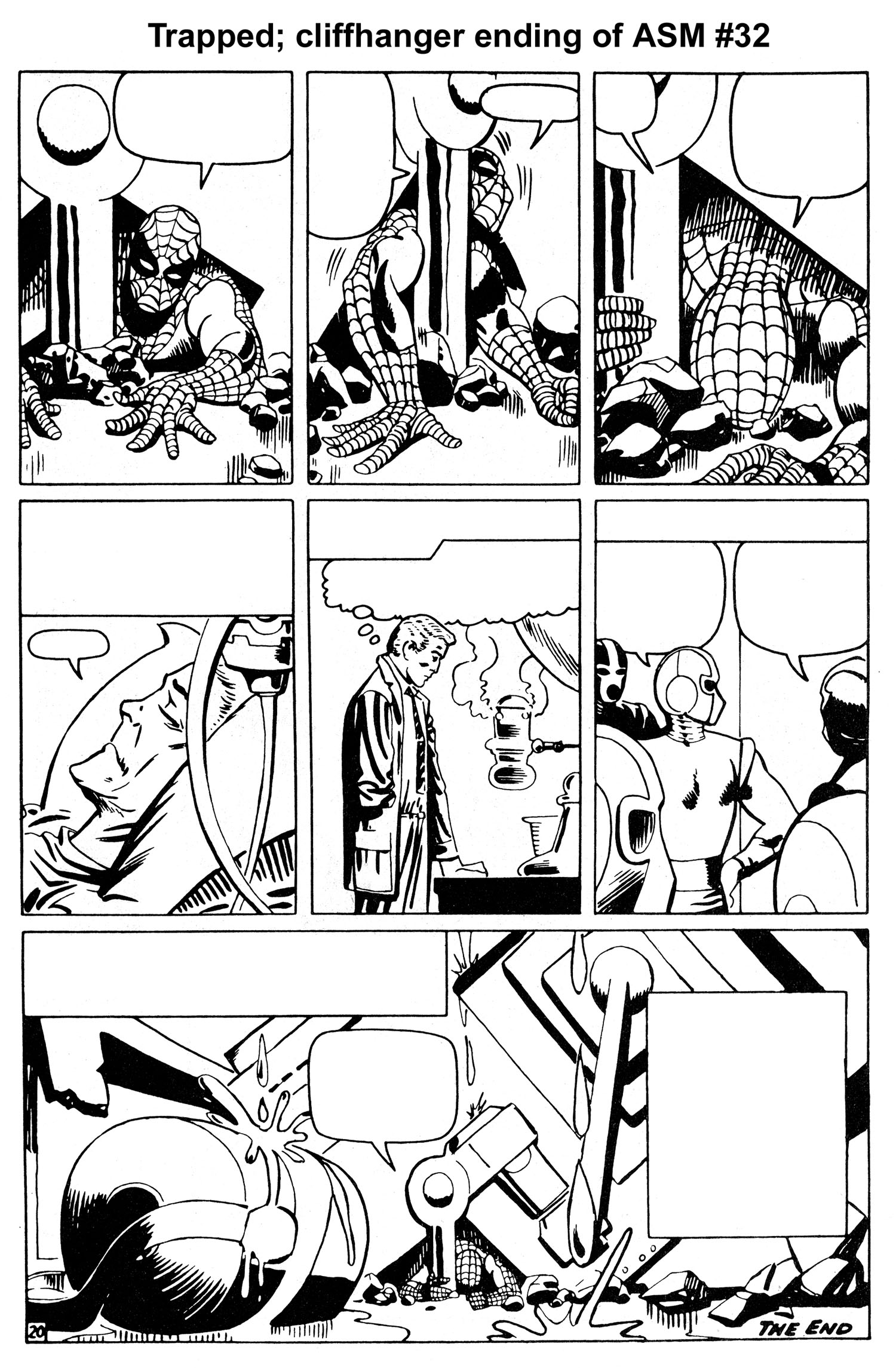

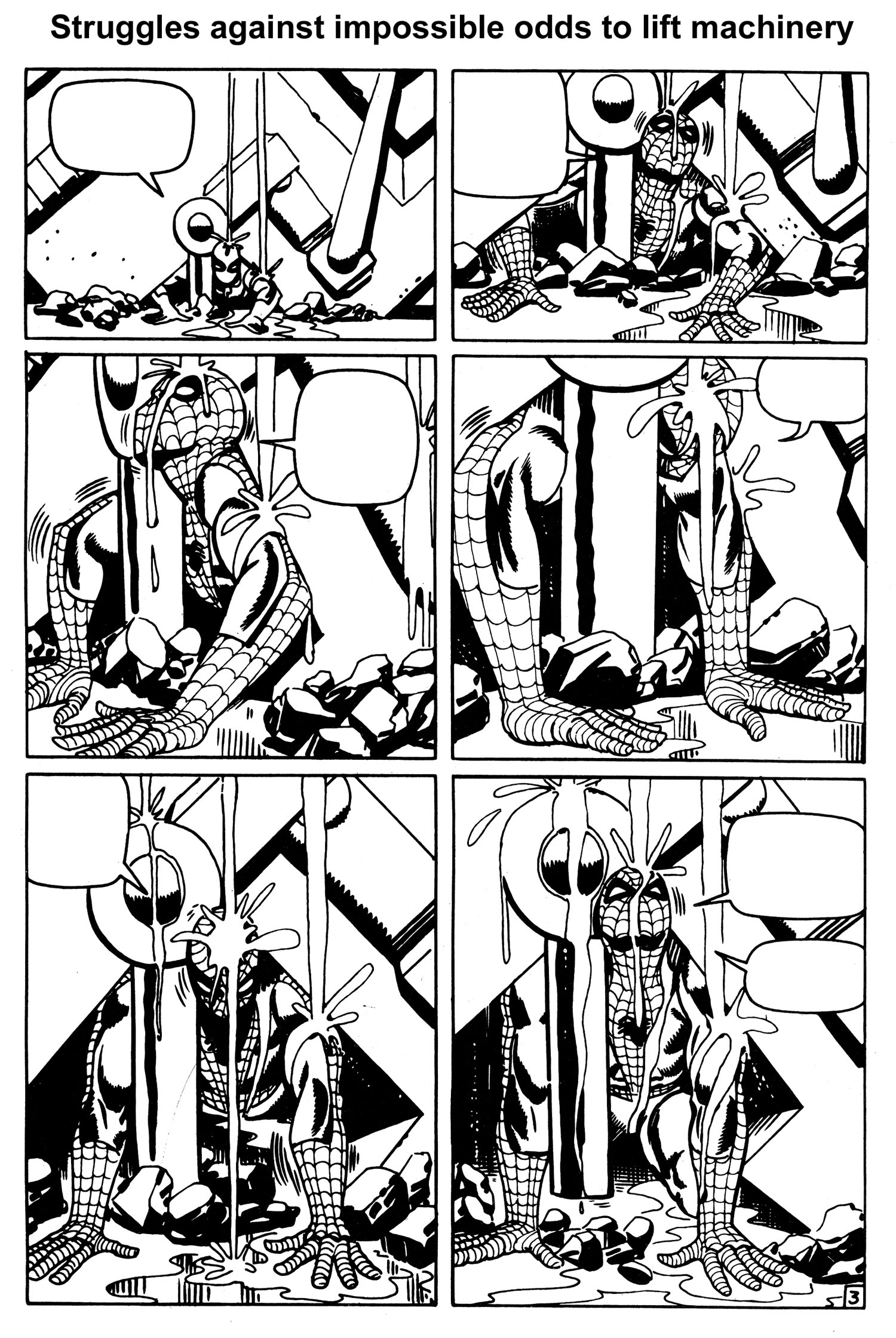

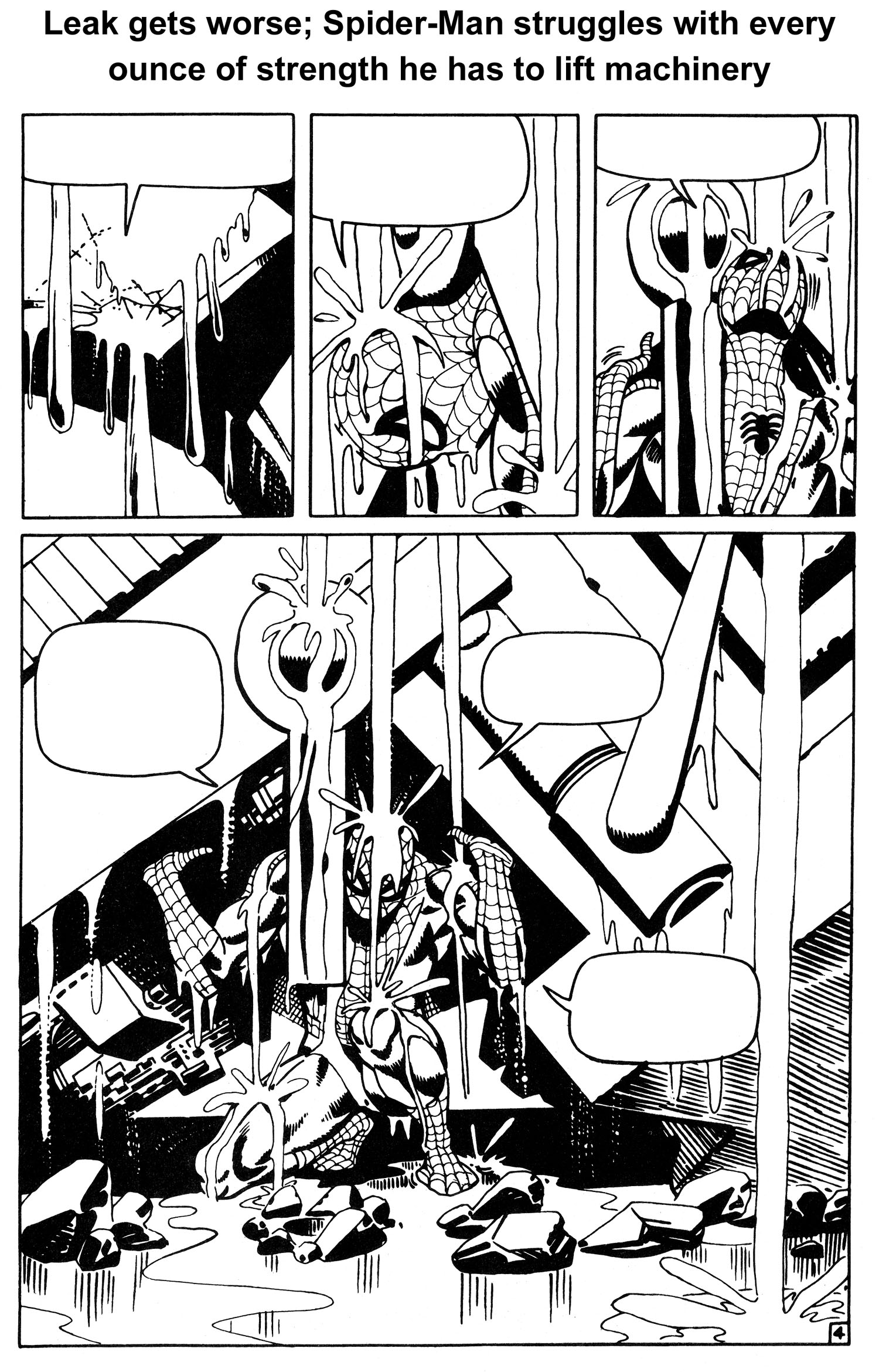

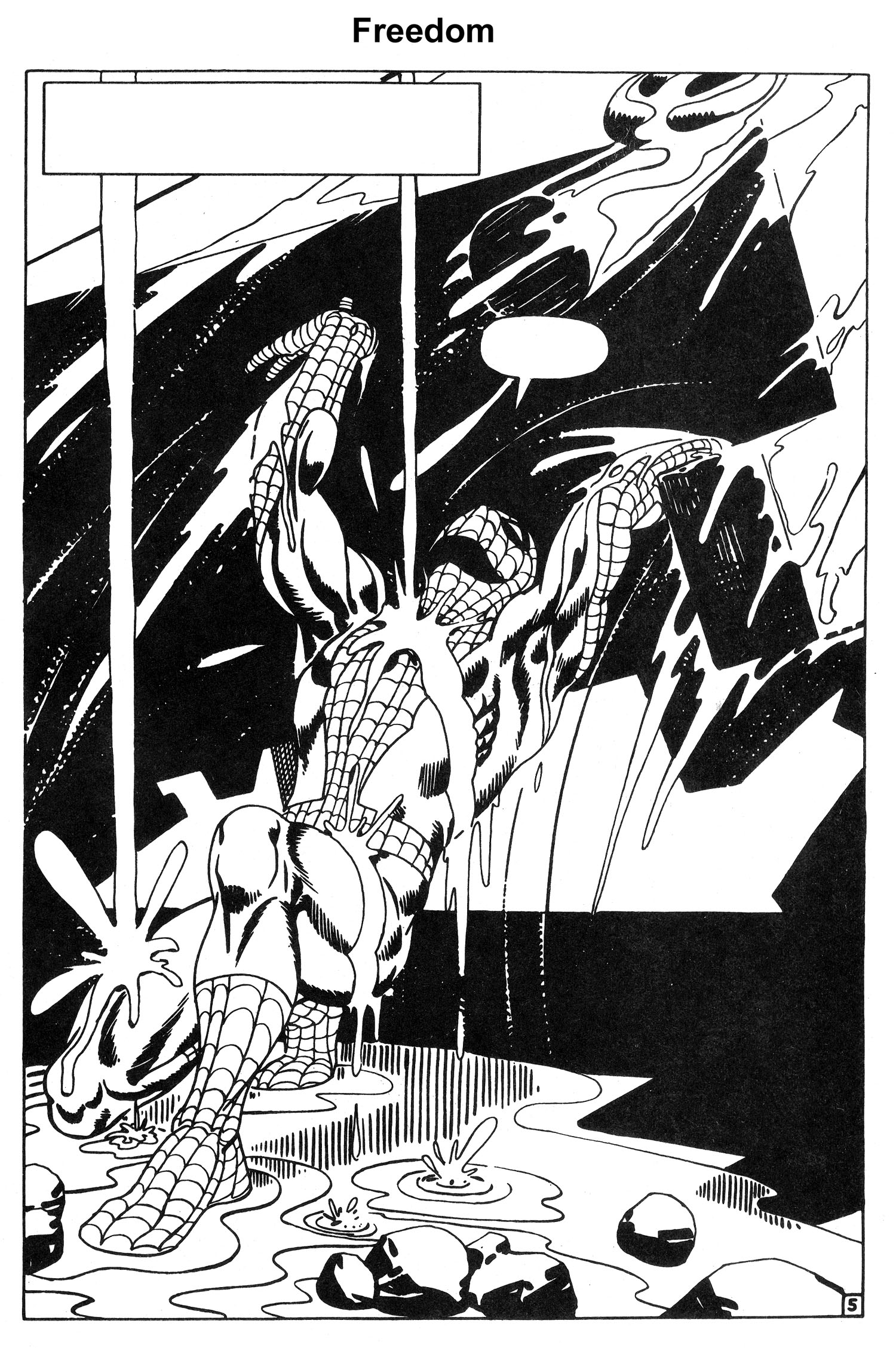

For the last three pages of issue #32 and the first five pages of issue #33, Ditko creates the most masterful bit of sequential art of the Silver Age, and possibly ANY age. It is an artistic tour de force that needs no words to convey the story. The drama, stakes and emotional tension of the main character could not possibly have been wound any higher as issue #32 came to a close. And I don’t think there was a sentient reader alive back then who wasn’t gnawing his/her fingernails to the bone waiting to find out what was going to happen in issue #33.

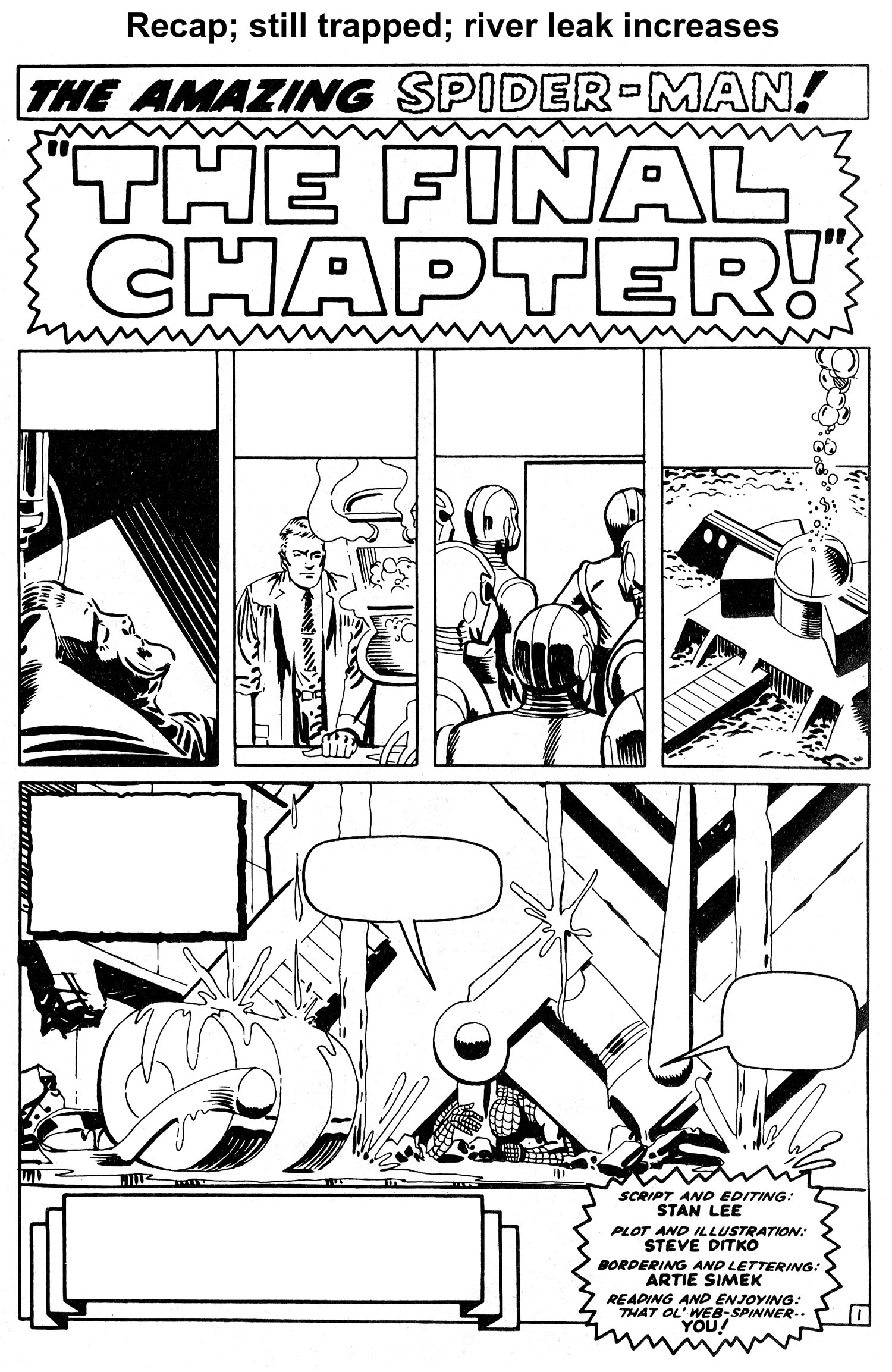

As issue #33, “The Final Chapter,” opens, the powerful visual sequence begun in the previous issue continues. After a four-panel recap, we see a hopelessly-trapped Spider-Man buried under the weight of an enormous mass of machinery as the main room of the underwater hideout of Dr. Octopus begins to flood. Aunt May is dying, and the serum he needs to save her lies on the floor in front of him, just out of reach.

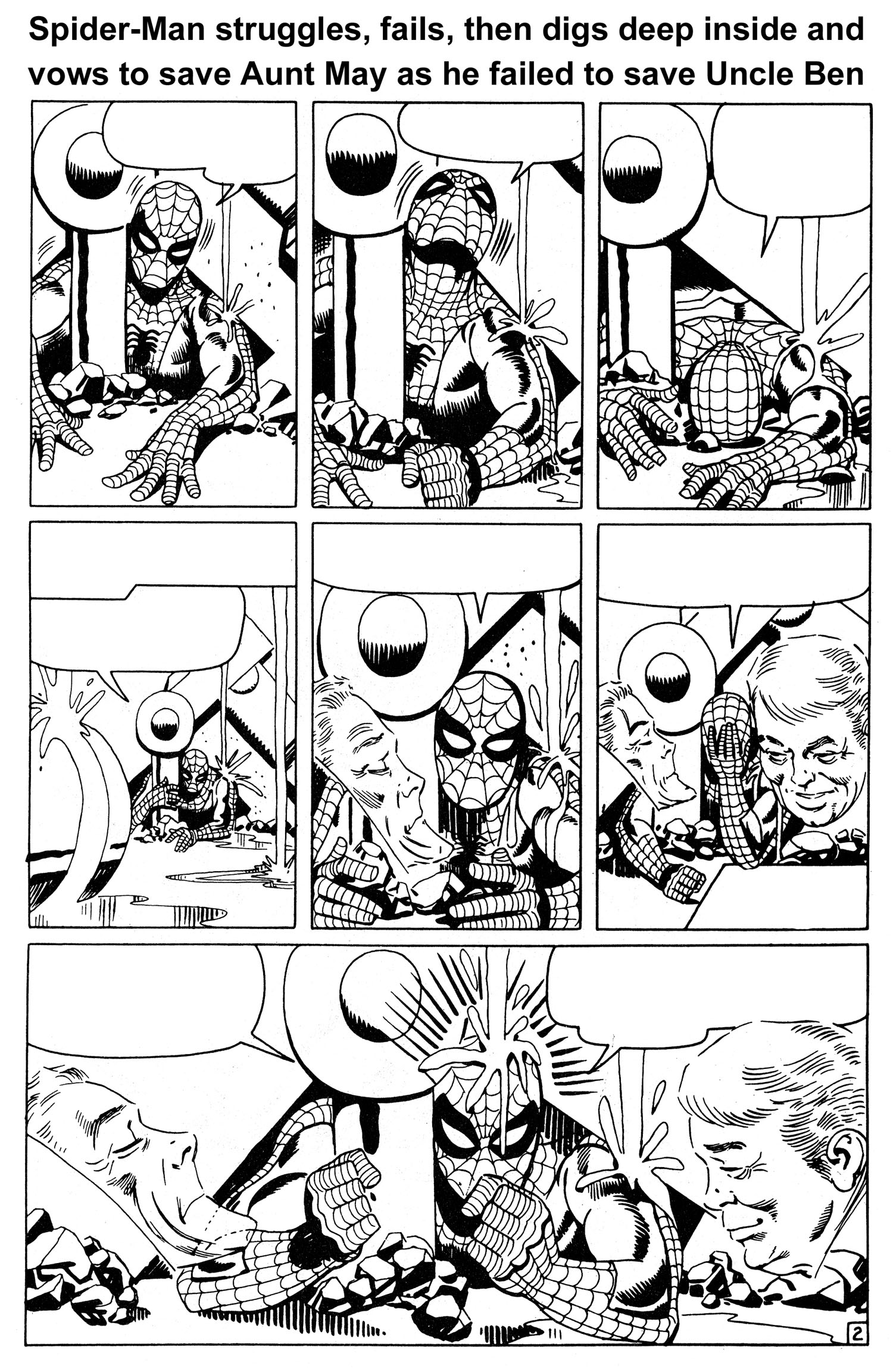

And just when you think it’s over for Spider-Man, and that he’s doomed to die, he once more thinks of Uncle Ben and Aunt May, taps a latent reservoir of sheer will and determination from his innermost being, and attempts one last time to break free. Ditko captures the agonizing struggle pitch perfectly, with sequential pacing that rivals that of the best comic book or film. And with one last mighty heave, he’s free (See Figures 7, 8, 9, 10 and 11).

But Ditko’s not finished. During the next 15 pages, Spider-Man must overcome even more physical and emotional adversity to save his aunt. But I’m not going to spoil the entire story arc. Grab a reprint of issue #33 and finish it yourself. You won’t regret it.

A few final points about the “Destiny” story arc and Ditko’s often underappreciated creativity.

First, the reason I showed wordless versions of the story’s pages was two-fold: to show how visually powerful Ditko’s storytelling abilities were, and to highlight just how crucial artists like Ditko and Kirby were to creating stories using the Marvel Method during the Silver Age.

Second, I want to make sure everyone understands just how much responsibility the artist had back then. In cinematic terms, Ditko not only co-wrote the screenplay, he was the storyboard artist, director, film editor, casting director, cameraman, cinematographer, production designer, costume designer, art director, stunt director, and set designer. Lee, on the other hand, co-wrote the screenplay, and did the “sound” editing.

So, while Lee’s dialogue certainly enhanced the story, Ditko was the creative force behind almost everything else. In that regards, if the story were a Corvette, Lee applied the paint job, pinstripes and some of the detailing, but Ditko designed the car, crafted all the parts, and assembled it.

‘Nuff said!

I gotta say, I’ve never read this story, but I have a somewhat snobbish attitude directed at the style of old comics, and I find it pretty strange to see people gushing about this comic and the sequence of Spider-man lifting something. (Peter David gushes about it in his writing for comics book, though less eloquently than you do, Russ). Don’t get me wrong, the art’s great, but still.

I just think of it as “That Spider-man comic where he lifts something really heavy! Like, really, really, heavy! You don’t think he’s gonna lift it, but he lifts it!”

It just seems kind of primitive to me.

And is that Ditko inventing the modern splash page at the end or something? (I read some earlier Ditko a long time ago and I don’t recall him using them in story…) I’m reminded of the joke from the cartoon Homestar Runner when a character is talking about an old comic and says “Anyways, Mushy could only talk in word clouds filled with commas, which I think had just been discovered and were apparently considered comic gold.”

Is this partially a generational thing, or am I just being a jerk? Were you a teenager when this story came out, Russ? I realize the same thing will happen to me, that the next generation will probably think Avengers verse X-men is the highlight of the superhero medium and Watchmen is shit.

Also, I’m kind of curious, did Ditko draw the balloons himself, and that’s why they appear in this art?

Response to pallas: The story culminating in ASM #33 is not simply about “lifting something,” in the same way that, say, “Pride and the Passion” is not just about “some guys pulling a cannon.”

One has to follow the storyline for at least two or three issues prior to issue #33 to appreciate the story’s emotional buildup of the main character that leads to “lifting something.”

Like any good book or film, one simply cannot read a few pages or view a few frames and appreciate the whole. It can’t be done.

I did NOT read “Amazing Spider-Man” #33 when it was first published. It was not until about four or five years later that I finally found a back issue and was able to read it. But it took me far longer to appreciate the power of the story because it was not until I assembled a near run of ASM in the early 1970s and read the issues prior, in order, that the complexity and emotional power of the story arc became clear. By then I was about 18 or 19 years old.

And as I allude to in my essay, even after repeated readings in succeeding years, the story retains its power — its timelessness.

I blocked out the words of the essay images to highlight Ditko’s art and pacing, and would have also deleted the balloons with PhotoShop if I’d had the time. So no, Ditko did not draw the balloons. The letterer did.

It’s an excellent suspense sequence.

Thanks for zapping out the copy. It’s fun to read this purely in terms of the visuals.

“And as I allude to in my essay, even after repeated readings in succeeding years, the story retains its power — its timelessness.”

Could be. A lot of my issues with old comics is one of style. Thought bubbles telling you exactly what a character is thinking. Heavy handed dialogue telling you what happened in the previous issue and foreshadowing what will happen in the next one. Repetition of tropes- because the book was never intended to be read back to back month to month. Dialogue that says what the art is showing. Footnotes that serve as a marketing gimmick moreso than a storytelling element. You need to get past those things to get at the “timeless” parts, and I’m not sure I can.

Granted, modern comics have many, many stylistic flaws, it’s just they tend to be different ones.

And I’m not saying my reading is fair or correct, but if you grew up with that style it might be easier to swallow.

I guess another way of saying it is if you grew up with the Bendis/ Mark Bagley version of the Spider-man story, would you still have emotional affect for the Ditko version if you read it as an adult? (Personally, I’m really not a fan of the character in general, so am not into either)

Some modern comics readers today gush like Scott Snyder invented Batman. For those who just got into Batman, he might as well might have.

pallas — I think it’s a valid critique of Silver Age comics — particularly Silver Age Marvels — to say that they were overwritten. That’s even obvious in the handful of pages I selected for the essay above, and is why I wiped away all of the text from the balloons and narration boxes.

By the same token, from my point of view, I think today’s comics tend to be underwritten.

That said, I can step into both worlds when I want to — which, I guess, is the key: one has to want to.

Someday, I may eventually learn to like Shakespeare, but to date I simply haven’t been willing to invest the effort necessary to get into the cadence and decipher the antiquated lingo and references. I mean, over the years I’ve read “Hamlet,” “Romeo and Juliet,” and a few of Shakespeare’s other plays, yet the enthusiasm was never really there. I’m certain that this has significantly curtailed my ability to appreciate his work. But I really don’t see that changing in the near future because I simply don’t care all that much about investing the intellectual capital necessary to be more appreciative of Shakespeare.

I’ve read Lee/Ditko Spider-Man sporadically since I was 8 or something. I’ve never really been that into it, though at various times and in various ways I’ve been able to appreciate bits and pieces.

I think my favorite part here is the sequence with Peter Parker vowing to save Aunt May, and then that panel where he knocks various detritus towards the reader…culminating in a round of bureaucratic phone tag. That’s nicely anti-climactic, and I think gets at the way that, in real life, the worst part about melodrama is that it almost always segues at once into the banal.

I like the verticality of the water dripping too, and the way it works off of spidey lifting up that machine.

I do wonder a little if the fact that you can remove the dialogue without it much mattering is exactly a compliment to Ditko in every way. Isn’t it a problem that the narrative is so familiar, and the action so pantomimed, that the words become redundant? Wouldn’t it be a better comic if the words and images were integrated, rather than just sort of casting sideways looks at each other?

Noah wrote: “I do wonder a little if the fact that you can remove the dialogue without it much mattering is exactly a compliment to Ditko in every way. Isn’t it a problem that the narrative is so familiar, and the action so pantomimed, that the words become redundant? Wouldn’t it be a better comic if the words and images were integrated, rather than just sort of casting sideways looks at each other?”

Ditko may have done so, in part, because with the Marvel Method requires an element of leading the writer along by the nose.

But as I mentioned previously, Lee was always a bit long-winded with his dialogue. Hell, even back in 1970 us fans would joke about how, as Captain America was in the middle of a wild melee, getting punched across the room, or knocked out a window, he still somehow managed to rattle off a five-minute soliloquy or scathing verbal dress-down of the bad guy(s) he was fighting.

I drew a “wordy panel” spoof myself about 15-20 years ago. Here it is:

http://home.comcast.net/~russ.maheras/wordy-panel-72dpi.jpg

I think the most efficient way to write and draw a strip is if one person does it all. Unfortunately, if the artist is lousy at writing dialogue, the negatives will probably outweigh the positives. And then you’re back to square one.

This really is an excellent, classic story. Although I read some of these stories as a kid, I wouldn’t say I grew up with them. If anything, I think I enjoyed them almost ironically (before I knew what that meant), laughing at the cheesy old dialogue, but still enjoying the action and plotting. But even though that layer of goofiness, the pure emotions and drama of this story stand out, with that sequence under the machinery still giving me chills whenever I see it. I love the pacing Ditko puts in there; on the second to last page, look at how the panels get “taller” in each tier, with Spidey seeming scrunched into a small space at the top of the page, and his strength steadily expanding the page itself as he pushes upward. And the body language! His face is covered, but Ditko conveys such exhaustion and frustration, giving way to determination and strength, all through the way the arms are tensed. It’s pretty amazing stuff.

Whoops, I meant the third-to-last page there when I was talking about the height of the panels.

“But as I mentioned previously, Lee was always a bit long-winded with his dialogue.”

I agree. Stan Lee is a terrible writer. I read Fantastic Four and Hulk and I couldn’t stand the writing. The only thing redeeming about those stories is the art and the imagination presented. Still, it really wasn’t worth the time I spent reading those books.

It’s not just Stan Lee though, Chris Claremont’s dialogue and narration is also kind of dreadful, from what I recall, and so is Marv Wolfman’s I think.

I’m not sure if its because they were presumably all Marvel style writers, and the idea of story blending with art was just so foreign to them? Or Claremont and Wolfman had the unfortunate situation where they learned by imitating or being mentored by Stan Lee or something?

The best you can say is the comics meant a lot to a lot people at the time, and while they have interesting ideas, they are written in a way which is thoroughly out of fashion.

pallas wrote: “I’m not sure if its because they were presumably all Marvel style writers, and the idea of story blending with art was just so foreign to them? Or Claremont and Wolfman had the unfortunate situation where they learned by imitating or being mentored by Stan Lee or something?”

That probably had a lot to do with it. Remember: Both Claremont and Wolfman started out as fans, so they wrote in the style of the work they admired (1960s Marvel). That obviously continued during their on-the-job-training at Marvel.

But as I mentioned above, I think much of today’s writing is too sparse and loose. I also hate the way thought balloons and narrative boxes are arbitrarily discouraged by many editors these days, as those are important and useful writing tools.

The job of any writer is to communicate, and if they aren’t doing that well — regardless of which style of writing they emulate — they have failed.

” I also hate the way thought balloons and narrative boxes are arbitrarily discouraged by many editors these days, as those are important and useful writing tools.”

I’m not sure that you can blame the editors, to a large extent I’d imagine many writers don’t want to use these tools: when writers like Moore, Morrison, Ellis, Vaughan, and whomever are doing indie books without editorial oversight, they usually aren’t using these tools either.

An excellent essay! You’ve certainly expounded on various comics-related stuff on the Web, but is this your first “formal” piece of comics criticism, Russ?

Got just ten minutes before leaving for work; just time for a few thoughts:

Re why Lee giving Ditko plotting credit and not Kirby, certainly much pressure from Ditko was involved, Lee being the shameless credit-hog that he is. (A transparently telling detail is that, to maintain the one-upmanship, “Lee, when he finally did start giving artist and plotting credit to Ditko, suddenly, after one issue, expand[ed] his own credits from “writer”…to both “editor and writer.”)

Why did Ditko — and not Kirby, who was hardly a mild-mannered wimp — feel free to do so? Kirby was a family man, with wife and kids to support. ( http://herocomplex.latimes.com/2012/04/09/growing-up-kirby-the-marvel-memories-of-jack-kirbys-son/#/0 ). Ditko had no one to worry about but himself…

By just about every account out there, Kirby wasn’t a confrontational person.

Also, can we please put the “family man, with a wife and kids to support” and other similar tropes to rest? While I don’t think it is your intention, these are used to obfuscate the very handsome income he enjoyed from Marvel, and make things sound like he and his family were living in struggling, hand-to-mouth circumstances. I suppose this picture is useful to fan-community demagogues who are out to smear Marvel, but it just isn’t so. Adjusted for inflation, he was making around $185,000 a year from the company in 1963, $210,000 in 1969, and $250,000 in 1975. He was making better money than more than 95% of the households in this country.

Incidentally, here’s the Long Island house Kirby and his family lived in during the 1960s:

http://www.redfin.com/NY/East-Williston/367-Congress-Ave-11596/home/20537000

Mike wrote: “An excellent essay! You’ve certainly expounded on various comics-related stuff on the Web, but is this your first “formal” piece of comics criticism, Russ?’

Might be. It’s certainly one of the most in-depth.

I’ve written a number of historical essays, including a colossal three-part index/analysis of the first 400 issues of “The Buyer’s Guide for Comic Fandom” (now “Comics Buyer’s Guide”), but not too many of what one could classify as “formal” criticism.

Mike wrote: “Re why Lee giving Ditko plotting credit and not Kirby, certainly much pressure from Ditko was involved, Lee being the shameless credit-hog that he is.”

Quite possible. Evidence certainly points in that direction.

Russ, is there any info about why Lee and Ditko fell out? Inquiring minds and all that….

RSM wrote about Jack Kirby: “Adjusted for inflation, he was making around $185,000 a year from the company in 1963, $210,000 in 1969, and $250,000 in 1975. He was making better money than more than 95% of the households in this country.”

Yep!

While my initial motivation for learning to draw comics was an altruistic love of the medium, as soon as I found out the page rates (circa the very early 1970s), this poor young scallywag saw huge dollar signs in his eyes.

Compared to what things were like when I was growing up, Kirby and other regularly employed comic book artists like John Buscema, Curt Swan, Joe Kubert, etc., were fabulously wealthy.

Noah wrote: “Russ, is there any info about why Lee and Ditko fell out? Inquiring minds and all that….”

I have some suspicions, but that’s all. However, I can say that, based on eaverything I know, it was probably not for any one single reason.

I can also say, quite conclusively, that it had nothing to do with arguments about the Green Goblin’s identity. That’s just a false rumor that started circulating decades ago and has somehow taken on a life of its own.

There were obvious personality conflicts. They reportedly stopped speaking to each other a good year-and-a-half before Ditko quit. According to Robert Beerbohm (click here), Ditko told him that he quit because Marvel reneged on royalty promises. He apparently tried to get Kirby to quit along with him.

Although it takes humungous blinders to defend Marvel, it doesn’t take “fan community demagogues” to smear them; their overwhelming greed, the tasteless product they excrete and their disregard for their founding artists speaks for itself (as recent news regarding Superman emphasizes, DC has these same faults to their discredit as well).

Jack Kirby more than earned the money he made by working constantly for absurd hours and producing at an exhaustive pace. He did work far in excess of what he was paid for at Marvel, establishing the bulk of the universe that the company continues to exploit to this day. It is verified by his contemporaries that before and after Marvel, Kirby wrote his own stories, and while at Marvel, Kirby most often created the narratives that he drew virtually complete, actually writing a rough draft of the text of the story that he invented in the margin. However, for his act of rewriting, paraphrasing and/or elaborating over Kirby’s narrative framework, Stan Lee took the entire “writing” credit and pay. Lee was unable to get away with the same trick with Ditko.

Robert and James, I don’t know that poor Russ’ thread is the best place to get into a knock-down drag-out about DC/Marvel corporate practices…. If you could both hold off, I’m sure there’ll be another more appropriate venue in the not too distant future. Okay?

“Poor Russ”?

Wasn’t the failure to pay Ditko royalties for cartoon series the final straw?

Steven wrote: “Wasn’t the failure to pay Ditko royalties for cartoon series the final straw?”

I don’t know.

James wrote: “However, for his act of rewriting, paraphrasing and/or elaborating over Kirby’s narrative framework, Stan Lee took the entire “writing” credit and pay. Lee was unable to get away with the same trick with Ditko.”

Which is what I asked in my essay. Why?

I’d really like to know.

Steven–

The animated series didn’t debut until September of ’67. Ditko quit either in late ’65 or early ’66. (His last issues of Amazing Spider-Man and Strange Tales have July ’66 cover dates. That means they hit the newsstands that April, and would probably have been completed no later than January.) Perhaps word might have gotten out about the animation deal around that time, but it seems unlikely.

RSM wrote: “Incidentally, here’s the Long Island house Kirby and his family lived in during the 1960s”

Wow! Growing up in Chicago, I lived in apartment buildings until I was 16. And when my parents did finally buy a 50-year old house in 1970, while I had my own room, it was so small it could hold my drawing table OR my single bed, but not both. So for years I slept in the unfinished, unheated attic or the unfinished, unheated basement. And forget central air in the summer. Our house had one tiny window air-conditioner, and it went in my parents’ bedroom window.

No, to me, Jack “King” Kirby was like a king in more ways than one!

Forget, “I wanna be like Mike!” I wanted to be like Jack Kirby!

James—

I do my best to avoid blinders about everything. I try to discuss everything as honestly as I can, and I try to avoid sidestepping complications.

If it was so easy to criticize Marvel and DC, perhaps you should ask why there is so much effort expended in falsifying complaints about them. Pretending Kirby wasn’t enjoying a high income from them is just one example. And since you allude to it, depicting Siegel and Shuster as the hapless victims of an egregious swindle is another.

By the way, I recommend you read the ruling in the Shuster heirs’ case, and particularly the correspondence between Paul Levitz and Shuster’s sister Jean Peavy. DC has bent over backwards to be fair and accommodating with them. The judge was clearly peeved that the court’s time was wasted even addressing the Shuster heirs’ claims. The ruling is here and the correspondence is here.

This isn’t to say that Marvel and DC don’t deserve criticism. They do over all sorts of things. One example is Marvel’s original owner Martin Goodman’s refusal to give creators any royalty interest in their work and material derived from it. But they do (and have done) a lot of things right as well, such as Goodman with the good up-front page rates. Adjusted for inflation, Kirby in the ’60s was paid $200 a page or so for pencils, and Ditko received the equivalent of about $300 a page for pencils and inks.

No one is claiming that Jack Kirby didn’t earn his money. However, he did not have to work at the pace he did to afford a comfortable lifestyle for himself and his family. He worked as hard as he did because he wanted to. It’s not unusual for comic-book cartoonists of that period to be workaholic personalities.

The evidence indicates he was very proud of the money he was making. He boasted about his Marvel income to the New York Times for a 1971 article on the comic-book field. He even posed for their photographer on the deck of his swimming pool at his California home.

As a rule, a successful business makes more money off its workers than the workers get paid. Welcome to capitalism. The only question is whether the workers are treated reasonably fairly. Kirby was well compensated for his ‘60s work at the time. He signed an agreement in 1972 that reaffirmed the company’s ownership of the material without any apparent conflict. He negotiated an extremely lucrative employment contract with them in 1975. The stage was set for him to sign an even better contract in 1978, and this was despite the fact his work at the time didn’t sell very well.

I am not an apologist for Stan Lee. I agree he took far more credit than he deserved for the writing of the material. However, he does deserve credit (for better or worse) for the final scripting of the books. I also think he deserves credit for co-creating the features. I don’t believe it was Kirby’s idea to include a revamped Human Torch in The Fantastic Four, or to make the X-Men students at an exclusive private school in Westchester County. Kirby’s accounts of the thematic impetus for the Hulk and Thor don’t jibe with the initial stories; what he described is what they became later on. What strike me as Lee’s (invariably crappy) ideas with those strips were what later got filtered out or minimized.

A big difference between Kirby and Ditko is that Ditko really doesn’t care about money all that much. With him, it really is the principle of the thing. Some acquaintances who dealt with him in the ‘80s told me he’d rather starve than violate his principles. By temperament, I think he was a lot more inclined than Kirby to confront people if he didn’t feel he was being treated fairly. Kirby did get Lee to give a little bit—I recall the credits became “Produced by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby” or some such after a certain point—but I don’t think he was ever able to push Lee as hard as Ditko did and get a plotting credit. I don’t think it was in him to go to the mat to that extent.

Yes, a good part of Kirby’s problem wasfirstly his enabling Stan Lee to take undeserved credit, secondly that he believed Martin Goodman’s handshake promises and made other bad business decisions and thirdly that he avoided conflict, rather, he stewed and continued to work.

Hey Robert,

200 dollars a page wouldn’t actually be that great a rate for a modern comic artist. If a modern comic artist can only do a book a month, you’d be looking at 48,000 a year.

And while I have not followed it, I suspect you are naive in regards to the Shuster case (saw your odd comment on the Beat that it was “obvious” the Shusters would lose)

A quick internet search turns up this article:

“Judicial Resistance to Copyright Law’s Inalienable

Right to Terminate Transfers”

“Congress could not

have more clearly manifested its intent that authors and their families should enjoy an inalienable right to terminate transfer, and the Second Circuit could not have

more patently violated it. The Steinbeck decision undercuts the integrity and clarity of Congress’s language, and unmoors the statutory termination of transfer”

http://scholarship.law.berkeley.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1790&context=facpubs

Other article:

“After judicial interpretation of the 1909 Act frustrated

this intent by upholding advance assignments of renewal terms, Congress

spoke unambiguously in 1976: “Termination of the grant may be effected

notwithstanding any agreement to the contrary . . . .” Yet recent decisions in

the Ninth and Second Circuits have eviscerated that clear congressional

command by permitting a grantee to renegotiate the terms of the grant so as

to frustrate recapture by the author’s family”

http://www.abaiplspring.org/coursematerials2011/docs/Pooh-Poohing%20Copyright%20Law.pdf

I want to be clear I am not an expert at this, just skimmed those articles and haven’t been following it. However I suspect that judges are basically saying to themselves “Well the law says that the author should get the rights back, but that would screw up the big business and mess up the grease in the capitalist system, so I’m going to invent a technicality so the big business wins.”

Actually, pallas, I think Robert’s page rate estimates are way low. Kirby was getting something like $75 a page circa 1970, which, if you plug that into the Dept. of Labor’s CPI Inflation Calculator, that equates to about $475 a page in today’s dollars.

I have some 1951 correspondence from Alfred Harvey, president of Harvey Comics, to a potential client, and he discusses general pages rates. He said the average was $50 a page for pencils and inks. He added that some of his artists get more; some less. In today’s dollars, that equates to about $450 a page — or about $9000 a month for a 20-page comic.

That’s pretty good dough!

Russ: “And I don’t think there was a sentient reader alive back then who wasn’t gnawing his/her fingernails to the bone waiting to find out what was going to happen in issue #33.”

The naive ones, you mean?

Oh, what the heck! I don’t want to, but I’ll ask just the same: isn’t the above melodrama upon melodrama, upon melodrama? Yeech!… I’m not against a bit of melodrama myself, mind, but the above seems, I don’t know… a bit ridiculous?

James: “Jack Kirby more than earned the money he made by working constantly for absurd hours and producing at an exhaustive pace.”

This, it seems to me, is the reason why some flaws can be detected in his drawings. Maybe I should have said it more explicitly in my “Funky Flashman” post, but since I didn’t, I’m saying it now. Also, what I did say in comments, if I remember correctly, is that no one cares now if Andrei Rublev had cold feet or was hungry, or something… Same for Kirby or any other artist.

Yes Domingos, I’ll go along with that, he rarely slowed down enoungh to show what he was really capable of.

And I have never heard anyone claim Kirby was impoverished, he worked as hard as he did to keep up a certin standard of living, but if RSM’s updating of his page rate is correct then the only reason he wasn’t, was his prolixity.

I agree that money was never a major motivasting factor for Ditko, but he was no less disgusted by Lee’s credit stealing than Kirby. A turning point for both Ditko and Kirby was an article in the NY Herald Tribune in 1966 in which the writer described Kirby as Lee’s flunky and Lee was overtly dismissive of Ditko. Ditko left Marvel soon after, it took Kirby a few more years to leave, but he ceased to create new concepts at that point.

It is possible to be both rich and underpaid. People who are rich and underpaid don’t tend to be revolutionaries, but they do tend to be litigants. Kirby is pretty much a textbook case.

Pallas–

There are a lot of reasons why today’s rates at Marvel and DC might be better, but I’d first like to know what they are. Can you fill us in?

A $48,000 annual income is decent money. Median household income in the U.S. is just above $50,000.

I never said at The Beat that it was “obvious” the Shusters would lose. There were two comments, one that’s up there right now and an earlier one I had taken down. I didn’t say that in either instance.

Law review articles are good things to go by in the absence of court decisions. However, once judges weigh in on a legal issue, what they say is what counts. Court precedents are what overwhelmingly determine how a law is interpreted. Two prior decisions backed up the judge’s ruling here, and they all will govern how future judges will see these situations, unless and until an appeals court overturns the circuit court decisions or there’s legislative redress.

And just because you disagree with or otherwise don’t like a judge’s decision, it doesn’t mean the judge is corrupt. Unless you can concretely show the judge has a conflict of interest, aspersions cast on his or her integrity are really out of line.

On a personal level, I think it was unethical for the Shusters to pursue this course of action even if the authors of the law-review articles are correct. Where I come from, you honor contracts unless the other party is engaging in obvious bad faith, regardless of if they’re to your advantage or not. The Shusters received over $600K, not counting inflation, from DC after signing that agreement, and they stood to make at least a couple of million more if they hadn’t pursued the termination. DC was not their enemy or behaving in a predatory manner.

Russ–

My page rate estimates for Kirby and Ditko were based on the 1963 numbers that Mark Evanier gave. A closer look at Kirby’s output relative to his reported income in 1969 backs your figures up.

James–

People such as Mark Evanier, Gary Groth, Stephen Bissette, and Patrick Ford don’t come right out and say that Kirby was struggling financially or otherwise poorly compensated. They engage in tropes that paint that picture. They’ll make polemical references to page rate amounts without indicating the value after inflation. They also get a lot of mileage from quoting all those defensive “I had to make a living” statements from that repugnantly exploitive ’89 interview that Gary conducted. These are the most frequent tactics.

Has Kirby or Ditko ever commented publicly about that Herald-Tribune article? I’ve come across a good deal of speculation about their reaction to that piece. I can understand why Ditko would have been ticked at Lee after reading it, but I don’t understand why Kirby would have. The offensive stuff about him came from the reporter, not Stan Lee. Lee was pretty complimentary of him in what was quoted.

It was my understanding that Kirby pulled back on new creations after Lee’s scripting completely subverted the Fantastic Four story that introduced Adam Warlock. Or is that wrong?

The date on that Herald-Tribune article is January 9, 1966. That’s right when Ditko would had to have quit.

Robert: you are right about that timeline….the article angered Kirby, but in his case it WAS the reporter slagging him rather than Lee…Lee was VERY directly insulting to Ditko in that article, though, and it did directly preceed Ditko leaving. Kirby stewed for several years on the implications of the article and how he saw them played out in Martin Goodman’s broken promises and Lee’s credit-hogging—and then yes, Lee’s changes to stories that Kirby was proud of were the last straws. He began making concept drawings for what would become the 4th World and holding some of his better splashes back. The later Marvel books before he left were well drawn but relatively standard stories that recycled his earlier concepts.

On the page rate of artists, I know Dave Sim was offered 500 dollars per page to draw a 3 page issue of Fables in 2005, because he put the contract on the Internet. My guess would be that’s one of the higher rates though:

http://albert.nickerson.tripod.com/creatorsbillofrightsfables.html

” However, once judges weigh in on a legal issue, what they say is what counts.”

That’s just another way of saying “Judges have temporal power.”

I never said the judge was corrupt, I said the court could have wanted the big business to win and (I suspect) twisted the words of the statute to make sure that happened. Court ruling aren’t mathematical equations, and judges can have a lot of power to get the result they want. That doesn’t mean the judges have anything to gain personally. Read some 5 to 4 Supreme Court cases and tell me the court system isn’t just another form of political bullshit.

I wouldn’t call it “corrupt” so much as I’d call it “how our legal system often operates”.

The authors guild states:

“Termination rights cannot be contracted away or waived in advance. Section 203 specifically provides protection of the author’s right to terminate, “notwithstanding any agreement to the contrary.” That covers both the original grant, and any later agreements.

So even if your publishing contract stated that you would not terminate the grant of rights at a later date, you may still terminate under Section 203. By the same token, any promise you later make not to terminate is equally invalid.”

http://authorsguild.org/services/copyright.attachment/terminatingtransfers/TerminatingTransfers.pdf

Looks like the DC business attorneys showed them! Your statement that the judge was “peeved” that authors think they have congress given rights is pure projection on your part. In fact there’s an article on the beat that said the judge had appeared to agree with the Shuster party during oral arguments.

I make no claims about the motives if the judge in this particular case, he or she could be following precedent from another judge who twisted the words of the statute, or maybe there’s a better argument that the judge is correct.. Like I said I haven’t followed it, and have not read enough on this issue to take a strong position I’m mainly reacting to the naivety in your statements.

The Sim contract also includes royalties of course. The impression I’ve gotten is DC treats creators a lot better today in terms of pay and royalties than Marvel does today, for example Chuck Dixon says he gets royalties from Bane:

http://www.comicsalliance.com/2012/07/23/bane-creators-royalties-chuck-dixon/

Creatively speaking, however, DC seems to be kind of a cesspool, and of course the better contracts may be a more recent invention- I think Neil Gaiman said if he created Sandman a little later it would have been a creator owned Vertigo book.

Domingos wrote regarding the ASM #32 cliffhanger ending: “The naive ones, you mean?”

First of all, I have to ask you if you’ve read the full three-issue arc, along with the two issues preceding it.

If you haven’t, then what’s the point of criticizing its parts?

Second, what’s wrong with melodrama? While it’s used as a perjorative by some elitist folks today, melodrama has been a key component of the arts since the beginning of recorded history under its true descriptor: trajedy.

I mean, for cryin’ out loud, “The Epic of Gilgamesh” is pure melodrama. Ditto for the Bible, Greek mythology and almost every other ancient story, or series of stories, passed down from generation. Shakespeare’s plays (at least the ones I’ve read) are pure melodrama, as are any number of classic novels, like “Moby Dick,” “A Tale of Two Cities,” “The Count of Monte Cristo,” and “Don Quixote.”

So why is it that when a comic book employs melodrama you seem to think it’s kitsch. Ditko’s later run of Spider-Man wasn’t kitsch. In fact, it’s depth and emotional complexity was unlike anything else being published during the Silver Age.

Frankly, I don’t think it has anything to do with the format and genre, I think it has everything to do with your fundamental belief that comics don’t merit serious consideration as true art — especially superhero comics.

Frickin’ typos! I hate writing right after I just woke up.

“trajedy” is obviously supposed to be “tragedy.”

Of course, that really how we emphasize it phonetically in “Chicaga.”

RSM wrote: “The date on that Herald-Tribune article is January 9, 1966. That’s right when Ditko would had to have quit.”

Actually, if you do the math, didn’t Ditko probably leave around March 1966?

ASM #38 was cover-dated July 1966, so if you walk it back three months (four, just to be conservative), we’re talking March.

The “Herald-Tribune” article may have been one of the proverbial straws, but we’ll never know unless Ditko publicly discusses it someday.

Pallas says: “Like I said I haven’t followed it, and have not read enough on this issue to take a strong position[.] I’m mainly reacting to the naivety [sic] in your statements.”

You haven’t followed the case, but you call me naive about it. OK…

Please define “naïve” or “naïvete.” I get the feeling we’re defining those words differently.

If you’re not taking a “strong position,” you could have fooled me. You seem pretty adamant that the judge was improperly ignoring the statutory language.

My responses to earlier parts of your comment:

Judges do have temporal power.

You wrote, “I suspect that judges are basically saying to themselves “Well the law says that the author should get the rights back, but that would screw up the big business and mess up the grease in the capitalist system, so I’m going to invent a technicality so the big business wins.” The inference there is that the judges are ruling in bad faith, which I do equate with at least a strong suggestion they’re corrupt.

By the way, there are at least two Supreme Court justices I consider corrupt: Scalia and Thomas. They both have ruled in several cases where they have obvious conflicts of interest.

That paper from the authors’ guild isn’t relevant to the Shuster case. It explicitly deals only with work copyrighted in 1978 or later. Section 203 doesn’t cover work before 1978.

I said the judge was “peeved” because that’s how I interpreted the snide and condescending language he used in addressing the Shusters’ arguments. Examples:

Now, perhaps someone might interpret the language in the passages as having been written by a judge who hadn’t all but completely lost patience with the Shuster heirs and their attorney. Fine.

As for The Beat article “that said the judge had appeared to agree with the Shuster party during oral arguments,” well, that’s an act of interpretation, too. I think the author would be the first to admit that this was the wrong call in light of the ruling–regardless of one’s perception of the judge’s tone in that instance.

Russ–

Back then, a newsstand comic with a July publication date would have been released in either March or April. The pub date jumped forward by three or four months to help keep the comics on the stands longer. In the early ’80s, I distinctly remember Christmas-themed comics, which came out in November, as having a March pub date.

You’d have to allow for at least two and probably three months for the completion of all production work, printing, and shipping to vendors. Ditko must have quit right around the time that article came out. He seems to have quit abruptly, too. He didn’t do covers for his last Spider-Man and Strange Tales issues. They had to collage them from the interior panels.

Shakespeare’s plays are definitely melodrama. The Epic of Gilgamesh maybe…though the tropes are sufficiently old and or alien that it doesn’t feel exactly like contemporary melodrama. A Tale of Two Cities is definitely melodrama; so it The Count of Monte Cristo. Moby Dick has melodramatic elements, but it’s pretty weird…I guess I’m on the fence about that. Don Quixote is satirizing melodrama, rather than being melodrama itself, I think (though I guess you could make a case that it’s participating in the tropes it’s ridiculing.)

RSM — I don’t think you are right about the timeline of cover dates and release dates. The rule of thumb I’m aware of during the Silver Age was if a book was cover-dated July, it actually hit the stands in May, and was shipped to the printer in April. Throw in an extra month for slop or schedule slippage we’re talking maybe four months tops. And that was the norm even in the 1950s.

Your example about holiday books could very well be different simply because they were annuals or quarterlies, meaning they’d have a much longer display date than a monthly comic book.

Keep in mind that in the mid-1970s I also worked for Charles Levy Circulating Company, which at that time was the ONLY distributor for comic books in the Chicago area. I was all over the comic book bundles when they came in each month, and I don’t ever recall seeing any evidence that would alter my impression of that general distribution timeline.

Noah — There are countless examples of melodrama in great literature, which is why I think Domingos’ criticism of ASM is so narrow-minded.

RSM — And now that I’ve thought about it even more, I’m even more certain I’m right. There was a period in the mid-1970s I seriously thought about starting my own comic book company. There was no direct market then, and the printer almost every comic book company used at that time was World Color Press in Sparta, Illinois. I contacted them to get basic information about printing and distribution, and while I did not save any of the info after the Atlas Comics debacle and DC implosion changed my mind, everything I recall seeing also fell in line with my comic book distribution timeline paradigm.

Keep in mind that it’s hard enough to wait even THREE months to find out that a monthly comic book you are bankrolling is a failure. Waiting six months be a total killer.

BTW I agree only regarding the rate of Kirby’s diminishing tolerance for what was done to him. But, talentless credit hogs and tasteless bullying corporate editors deserve nothing but contempt and it is becoming clearer by the day that the minions of unrestricted capitalism stand in opposition to democracy and can be considered akin to Kirby’s “anti-life”.

Russ–

I did some checking, and I think you’re right, too. It seems the advance dating jumped from two to three months sometime in the ’70s.

This, by the way, was the Christmas-themed comic I had in mind. I’m almost sure I bought it the weekend after Thanksgiving at a local drugstore in 1980. It has a March 1981 cover date.

The problem here is that, I gather from your description, the story it *nothing* but manichean melodrama (I said that I don’t mind some melodrama myself, didn’t I? Why is it that no one reads what I write? It was the same thing in the Kirby post: damn sacred cows!). I mentioned the naive readers because, obviously Spider-Man would lift the heavy machinery, and obviously he would defeat the bad guys,and obviously he would save aunty May.

No Robert, I don’t take that as the judge being peeved, as a basic observation, a judge won’t write “This case could have gone either way, but since its my job to say someone wins, I flipped a coin and A wins” when deciding a case. As a general matter, they’ll pretend that someone has to win and act dismissive towards the losing parties argument. That’s kind of their job, you know?

As for your moral argument about the Shusters honoring contacts, we’ll have to agree to disagree.

Its interesting how when a corporation lobbies to alter the length of copyright, its ok and business as usual, but when the authors exercise a right given by congress to share a part of the lobbied for extended copyright term, you think its moral turpitude on the part of the authors. Its also funny that the Schusters somehow bargained for a right in 1992 that didn’t exist yet. This isn’t about honoring contracts, its about how lobbied for goodies are going to be given out to constituents.

“In 1998, Congress extended copyrights AGAIN. This time, for any copyright formed before 1978, Congress just added a flat 20 years. So Superman will now stay in copyright for 95 years, or until 2033. However, this time, that extra 20 years is available not only to authors and their heirs, but also to the ESTATES of authors. So Joe Shuster’s estate (executed by his nephew) will certainly be exercising their right of termination, which will be in 2013.”

http://goodcomics.comicbookresources.com/2008/03/30/superman-copyright-faq/

I laughed when I saw the heads of May and Ben floating, so, it’s not completely bad, I guess…

Pallas–

As a basic observation, no, judges don’t hector the attorneys they rule against in their decisions. They just lay out their reasoning in the case.

I don’t know why you’re equating legislative lobbying with abrogation of contract. They’re entirely different things.

I don’t think it’s unethical to terminate a copyright if you’re an entitled party. However, I do think it’s unethical to enter into an agreement, repeatedly reaffirm your intention to honor it, and then turn around and abrogate it because you apparently decide it’s inconvenient.

Judicial decisions trump columns by comics-press writers. Sad but true.

The premise of the termination language is the idea that authors are in a bad bargaining position when they begin their careers, and there’s the opportunity to get the copyright back, regardless of what the contract says.

I guess its a position to say that such statutes are wrong and the worship of contract language is the overriding moral principle. That consumer protection laws are wrong, that people should be able to sell themselves into indenture servitude, put their organs up for sale or whatever. I believe there was a Shakespeare play about a contract for a pound of flesh. I guess its a very old moral position.

Pallas–

I don’t discuss issues with people who make the sort of absurdist equivalencies that you did in your second paragraph. It’s pointless.

——————

Domingos Isabelinho says:

…I don’t want to, but I’ll ask just the same: isn’t the above melodrama upon melodrama, upon melodrama? Yeech!… I’m not against a bit of melodrama myself, mind, but the above seems, I don’t know… a bit ridiculous?

——————

About the 8-page sequence of that story-arc Russ calls “great,” I’d consider it a towering achievement in the field of superhero comics; in the way that “Raiders of the Lost Ark” was the epitome of of the Republic Pictures film serials approach.

(Re the latter, don’t the titles say it all? “Canadian Mounties vs. Atomic Invaders,” “Zombies of the Stratosphere,” “Radar Men from the Moon,” “The Purple Monster Strikes”… [Probably nowhere near as great fun as they sound, alas…])

What superhero comics story comes to mind that achieved what Ditko did here? The intense concentration of peril, desperation, hero thinking of what’s meaningful to him, calling on his inner reserves to overcome crushing travails?

Visually, it’s perfection in achieving its goals: the massive, angular shapes of the machinery pinning Peter Parker down; the water drawn as heavy, viscous shapes to enhance its menace; the struggles, anguish and determination clearly conveyed through body language alone; and the exhilarating, heroic moment as he throws off the crushingly oppressive mass.

Come to think of it, a certain comics sequence comes to mind: I think it was a Ditko story of the Hulk, where imprisoned, the character hammers over and over and over and over against a prison wall, until finally breaking free. (Or was it Kirby and The Thing?)

In both cases, cannot one see a thinly-veiled symbolic structure, with emotional/real-world troubles, challenges and obstacles embodied as physical, melodramatically-intense ones?

Some related thoughts by Raymond Chandler; ammo for Russ’ argument:

————————-

When a book, any sort of book, reaches a certain intensity of artistic performance, it becomes literature. That intensity may be a matter of style, situation, character, emotional tone, or idea, or half a dozen other things. It may also be a perfection of control over the movement of a story similar to the control a great pitcher has over the ball. … Dumas Père had it. Dickens, allowing for his Victorian muddle, had it …

————————–

http://chrisroutledge.co.uk/writing/raymond-chandler-on-writing/

And…

——————————–

…what about the mystery’s widely admitted second-rate literary status? What is the basis for this reputation? The mystery’s inferiority is linked to its use of the formula of “flattening.” Characters are simplified so that they respond to the story rather than their personal psychological needs or higher aspirations. Plots are streamlined so that the variations are more clearly seen against the backdrop of uniform expectations. Settings are stylized so that topology rather than geography dominates. Isn’t it the case that the mystery story’s second-rate status is precisely what makes it so valuable?…

———————————-

The infinitely more complex and fascinating whole at http://art3idea.psu.edu/boundaries/documents/mysteries.html

Domingos wrote: “I laughed when I saw the heads of May and Ben floating, so, it’s not completely bad, I guess…”

Just as you also no doubt laughed hilariously at, say, “A Christmas Carol,” or “Hamlet.”

————————

Domingos wrote: “The problem here is that, I gather from your description, the story it *nothing* but manichean melodrama (I said that I don’t mind some melodrama myself, didn’t I? Why is it that no one reads what I write? It was the same thing in the Kirby post: damn sacred cows!). I mentioned the naive readers because, obviously Spider-Man would lift the heavy machinery, and obviously he would defeat the bad guys,and obviously he would save aunty May.”

Your “audience naiveté” charge rings hollow because the way Ditko built the story, there were no guarantees about anything. In fact, Ditko could have easily directed the story into the the direction of Aunt May’s death if he’d wanted to. After all, Uncle Ben’s death was an integral part of the entire Spider-Man mythos.

Ditko instead chose to use the saving of Aunt May as a vehicle of ultimate redemption for Peter’s direct responsibility of Uncle Ben’s death — something that was perfectly in line with his quest to elevatue the developing heroism of Peter Parker/Spider-Man.

Another reason your “audience naiveté” argument rings hollow is because there are lots of instances in great literature or film where the astute know in advance certain parts of a story’s outcome. For example, is there anyone who did not know well in advance that somehow Edmond Dantès would not find a way to escape his unescapable prison and get his revenge in the novel “The Count of Monte Cristo?” And is there anyone who did not know from the very beginning of Shakespeare’s “The Tragedy of Julius Caesar” as to how it was going to end? Ditto for the second highest-grossing film of all time, James Cameron’s “Titanic.”

The fact that you haven’t even read Ditko’s work undercuts your criticism’s weight, making it little more than background noise at this point.

“Ditko could have easily directed the story into the the direction of Aunt May’s death if he’d wanted to”

I’m not sure I buy that. When everyone talks about the death of Gwen Stacey, they talk about it as the story that broke all the rules and blew everyone’s mind and something that could have only happened when the Silver Age was over, the hero failing to save the day.

You seem to be positing Ditko as the best SIlver Age writer and yet somehow not a silver age writer?

Also, in Amazing Fantasy #15 he’s doing a two dimensional “morality play” about great power and great responsibility, does’t that mean the hero has to be rewarded for doing the right thing? I guess your positing Ditko could have subverted his own themes, and readers could have expected him to?

You know what they say about superheroes: they die and, then, they get better.

Your repeated appeal to the authorities fails completely, Russ: The Count of Monte Cristo, Titanic? Is that your idea of great art?

On the other hand everybody knows that Julius Cesar was assassinated, that’s true. That’s why I imagine a “sentient [theater goer] […] gnawing his/her fingernails to the bone waiting to find out what was going to happen.”

Pallas — It’s easy to second guess the direction of the series 50 years later, but one has to look at it from the audiences point of view in 1965. When the “Destiny” story arc was published the “Amazing Spider-Man” comic book was just about three years old, so Uncle Ben’s death was still relatively recent. And Aunt May’s heath was frail for nearly two years — ever since her operation in issue #9. And while it’s possible that Ditko had some sort of edict from Lee early on that when plotting, no major characters would be killed off, but even if that was the case, the readers wouldn’t know that back then.

Domingos — Hey, I really like “The Count of Monte Cristo.” And while you apparently don’t think much of the story, literary experts seem to think it merits classic status. As for “Titanic,” I wasn’t citing it as something I thought was great — that stature was decided by the masses.

And all this is besides the point. If yoy spent just a few minutes thinking about it with an open mind, you could probably make a list of your own of literary or film masterpieces that had predictable elements to them.

What matters in such cases is how the story is told and how the characters interact.

That’s not exactly what matters (much) to me at least, but let me remind you that all this started with your assumption that readers were “gnawing [their] fingernails to the bone waiting to find out what was going to happen” in a formulaic story.

Anyway, in the end this doesn’t matter much. My problems with this story run a lot deeper.

“The fact that you haven’t even read Ditko’s work undercuts your criticism’s weight…”

Have you forgotten what site you’re writing for, Russ? This is the Hooded Utilitarian, and we don’t need to read the things we criticize here!

Matt H. — Damn! How right you are!

But I can’t really judge. I can remember a few times when I threw in my critical two cents about a book/film I hadn’t read/seen. But I really try to avoid that.

I’m not criticizing anything, I’m writing comments under a post. Even so I can see the images above, can’t I’

I can also read Russ’s paraphrases, I guess. That’s what I’m commenting. If they’re inacurate that’s not my fault.

Really, a lot of stories, great and mediocre, you can see the ending coming a mile away. In Shakespeare’s comedies, everybody lives. In his tragedies, everybody dies. In the divine comedy, we know that dante will eventually become enlightened. We knew from the beginning that Odysseus will eventually return home. etc etc etc

somerandomdumbass — Great examples!

Like I said in my essay, “Some argue that great art or literature is timeless, and that it appeals to our emotions in a compelling and riveting way. Others argue that it is something that breaks new ground.”

And I don’t think breaking new ground has to mean a story path must be totally unguessable to the very end. One may break new ground by reimagining a classic story in a new way with different characters. This same “reimaging” process has been used in the arts by different cultures since ancient times.

Domingos wrote: “I can also read Russ’s paraphrases, I guess. That’s what I’m commenting. If they’re inacurate that’s not my fault.”

Sure it is. Read ’em yourself!

It’s not like these issues of “Amazing Spider-Man” are hard to come by. They’ve probably been reprinted a dozen or more times, including several times in the past 5-10 years.

I give up: sometimes I have the impression that people can’t read. Or is it that bad faith clouds their reading abilities?

I’ll give it one last shot though: if people know the ending in those examples they must be reading them for other reasons than to “gnawing [their] fingernails to the bone waiting to find out what was going to happen.” Why is it that this little scrap of prose gets completely forgotten when commenting my comments? See what I mean when I talk about bad faith?

—————————-

Domingos Isabelinho says:

I give up: sometimes I have the impression that people can’t read. Or is it that bad faith clouds their reading abilities?

—————————–

Ah, the irony! It’s like reading in Goebbels’ diaries his describing Churchill as a “warmonger” who plunged Europe into chaos and destruction…

—————————–

I’ll give it one last shot though: if people know the ending in those examples they must be reading them for other reasons than to “gnawing [their] fingernails to the bone waiting to find out what was going to happen.” Why is it that this little scrap of prose gets completely forgotten when commenting my comments?

——————————

There’s no contradiction there. Note the wording: Not “waiting to find out what the ending was going to be,” with the hero predictably triumphant, but “waiting to find out what was going to happen.”

In other words to see, how are they going to get out of this predicament?

People can both be aware that tied-onto-the-tracks Pearl White won’t get crushed by the oncoming train, James Bond won’t get bisected by a buzz-saw/laser beam (as in book and movie of “Goldfinger”), that Hercules will prevail in his challenges, Odysseus will somehow escape the Cyclops and make it home, and still anxiously be wondering, how will they do it?

————————

pallas says:

[Russ,] You seem to be positing Ditko as the best Silver Age writer…

————————–

Did Russ say or imply that? He did not. He didn’t even say the “Destiny” story arc tales were the best comics stories of that time.

————————–

R. Maheras says:

For the last three pages of issue #32 and the first five pages of issue #33, Ditko creates the most masterful bit of sequential art of the Silver Age, and possibly ANY [comics] age.

—————————

Again, what he saved his highest praise for was a sequence where Ditko, as writer and artist, created something extraordinarily powerful and effective.

Mike: “Ah, the irony! It’s like reading in Goebbels’ diaries his describing Churchill as a “warmonger” who plunged Europe into chaos and destruction…”

Examples, please.

Oh and, OK, how will Spider-Man lift the heavy machinery? With his muscles, maybe? Just a thought…

“He didn’t even say the “Destiny” story arc tales were the best comics stories of that time.

”

Mike, perhaps you should reread the first paragraph of the article.

“OK, how will Spider-Man lift the heavy machinery? With his muscles, maybe? Just a thought…

”

I’m guessing he THINKS REALLY HARD ABOUT TRYING REALLY HARD TO USE HIS MUSCLES REALLY HARD AS THE NARRATION EXPLAINS THAT HE IS FLEXING HIS MUSCLES REALLY HARD.

But in all seriousness part of the fun of the genre is pretending the hero might die as you read it. I don’t think it’s really a sign of naivette per se, it’s just part of the consensual illusion.

Pallas — That’s a good way to put it — “consensual illusion.” That unwritten “contract” with the audience has been a part of the arts since the very beginning — especially for plays, the opera, etc.

Domingos’ contempt for its usage in comics is either elitism or contrarianism.

It’a called suspension of disbelief, I believe.

I’d think that usually is used more for stuff like, “You’ll believe a man can fly!”

Much entertaining info at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Suspension_of_disbelief ; including…

——————–

Some find it strange that while some audience members took issue with the flimsiness of Superman’s disguise, they didn’t take issue with the idea of the existence of a superbeing whose only weakness was kryptonite. One arguing from the theory of suspension of disbelief would contend that while Superman’s abilities and vulnerabilities are the foundational premises the audience accepted as their part of the initial deal; they did not accept a persistent inability for otherwise normal characters to recognize a close colleague solely because of minor changes in clothing.

Gary Larson discussed the question with regard to his comic strip, The Far Side; he noted that readers wrote him to complain that a male mosquito referred to his job sucking blood when it is in fact the females that drain blood, but that the same readers accepted that the mosquitoes live in houses, wear clothes, and speak English.

——————–

——————–

pallas says:

“He didn’t even say the “Destiny” story arc tales were the best comics stories of that time.”

Mike, perhaps you should reread the first paragraph of the article.

———————

(??? Scrolls up, reads…) Oh, pshaw!

(Scraping egg from face) Well, with EC comics dead, those probably were “the best comics stories of that time”!

———————–

Domingos Isabelinho says:

Mike: “Ah, the irony! It’s like reading in Goebbels’ diaries his describing Churchill as a “warmonger” who plunged Europe into chaos and destruction…”

Examples, please.

————————-

The irony is your saying, “that bad faith clouds [others’] reading abilities.”

Russ wrote:

————————–

The drama, stakes and emotional tension of the main character could not possibly have been wound any higher as issue #32 came to a close. And I don’t think there was a sentient reader alive back then who wasn’t gnawing his/her fingernails to the bone waiting to find out what was going to happen in issue #33.

—————————

And you asserted that:

————————–