I am a generally happy person. A cockeyed optimist. A Pollyanna. Hell, you know, I’m from the Midwest. I like to like things, and I try very hard to do so. As a self-directed blogger with no editorial mandate to adhere to but my own, I skip merrily through the world of East Asian comics, content to linger over what pleases me. I rhapsodize over the books I enjoy and blow through the rest as quickly as possible—like a panicked sprint through the unexpected cloud of gnats on an otherwise peaceful summer stroll.

For a person like me, “hate” is a fairly nebulous concept, and not all that easily accepted or even understood. For me to hate something—to really loathe a thing—it needs to hit me where it hurts. I can’t vigorously hate a book or a comic or a Broadway musical, say, for simply being incompetent (*cough* Baseball Heaven *cough*). I must be truly, inconsolably offended in order to come even close to real hate.

That said, there are a number of comics I’ve disliked intensely over the years—mainly since I began reviewing things I wouldn’t necessarily choose for myself. Notable objects of my rage have included gender-regressive shoujo manga like Black Bird; creepy, campy BL like Tricky Prince; and the fat-shaming caricature that is Ugly Duckling’s Love Revolution. One of these titles even prompted an experiment to discover how often and how thoroughly I must trash a single series before the publisher would stop sending me new volumes (answer: to infinity). The thing is, when I go back and read my reviews of these books, each of which has incited rage, they seem kind of… weak. Despite my wrath, I could never truly commit to hating these comics, due to their lack of serious intent. Nobody thinks Tricky Prince is Serious Business, including Tricky Prince, and it’s hard to work up genuine, lasting hatred over something that was intended to be disposable from the start.

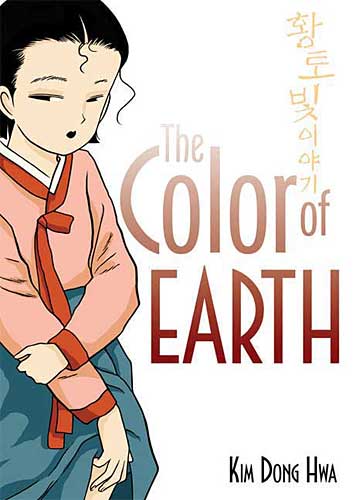

Then came the Color trilogy.

|

|

|

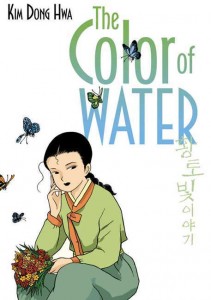

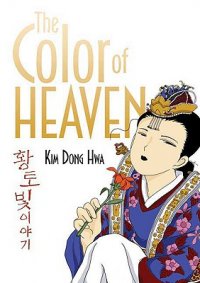

In 2010, I volunteered to host the first manhwa edition of the Manga Moveable Feast. A number of titles were suggested and put to a vote, including some personal favorites, like Byun Byung-Jun’s quirky short comic Run, Bong-Gu, Run!, Uhm JungHyum’s moody romance Forest of Gray City, and JiUn Yun’s sumptuous collection of ghost stories, Time and Again. Unsurprisingly, however, the vote ultimately came down to Kim Dong Hwa’s critically acclaimed manhwa trilogy, The Color of Earth, The Color of Water, and The Color of Heaven, published in English by the lovely folks at First Second. Though I was a big fan of Korean comics in general (and certainly knew of Kim’s series), I hadn’t read read more than a few excerpts myself, so I dug in with verve. And then the hate… oh the hate… it was like nothing I’d experienced as a comics reader before.

The Color trilogy is a coming-of-age story revolving around Ehwa, a young girl in pre-industrial Korea who is being raised by her mother—a widow who runs the local tavern. The story spans Ehwa’s life from the age of seven (when she is first made aware of the existence of penises, thanks to a boys’ pissing contest) through her wedding night (when she gets to know a very special penis on more intimate terms). I choose these parenthetical descriptions purposefully, because that’s what this series is really about: penises and the pursuit of same—that is, when it’s not too busy going on about the lusty beauty of a ripening young woman (yes, these words are chosen purposefully as well).

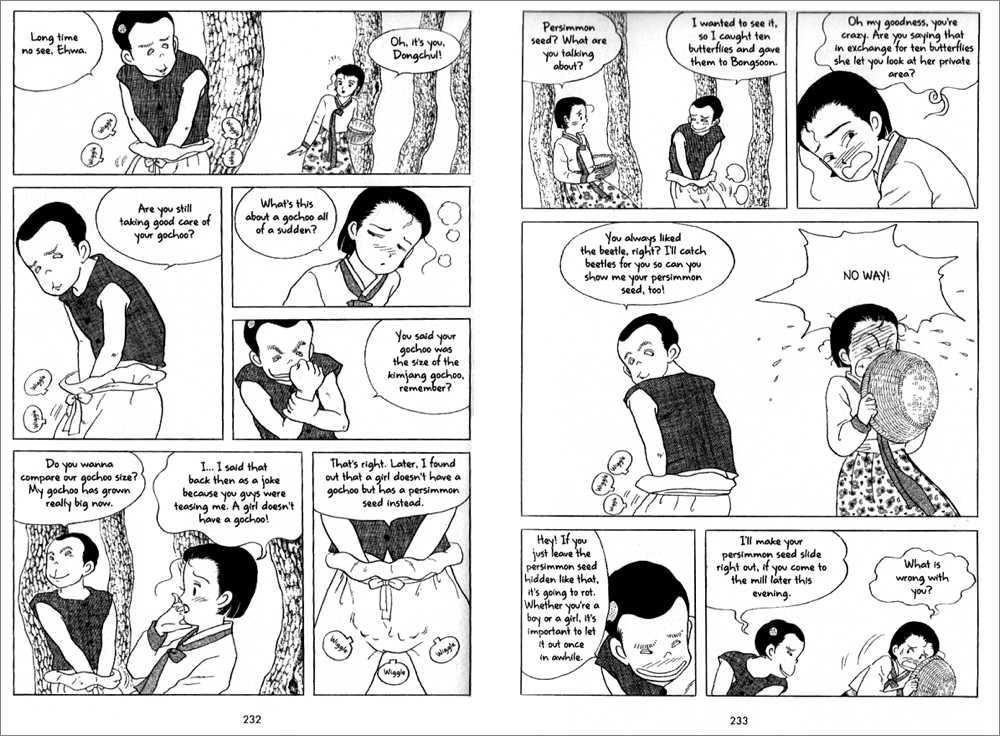

First, the penises. As I mentioned, the story opens with Ehwa, at seven, stumbling upon a pissing match between two local boys. The boys are deeply proud of their own “gachoo” (chili peppers, also a euphemism for “penis”) and they ask Ehwa to show them hers. This sends Ehwa into a tizzy, as she wonders if not having one indicates that she’s deformed. One of these boys is so consumed by his love affair with his own penis that he will later be portrayed as being unable to take his hands off of it.

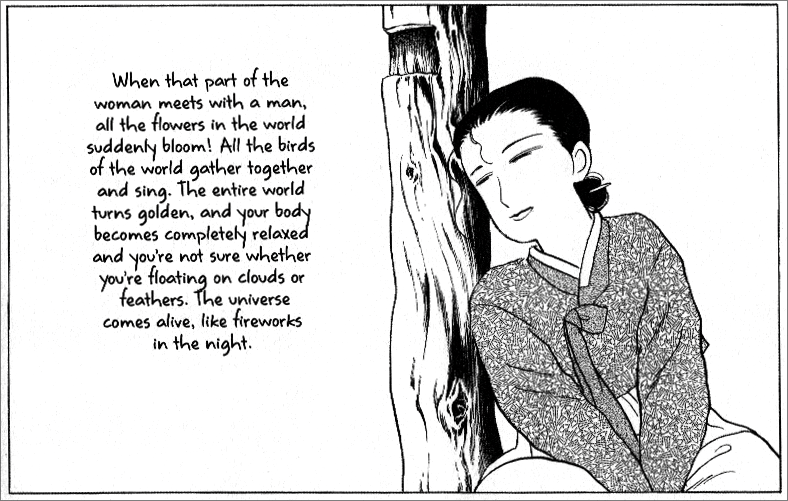

Hey, why should he? It’s a really awesome thing, that gachoo. As Ehwa’s mom explains to her later (after buying a whole lot of ginseng to cook with in order to boost the, uh, energy levels of her traveling suitor known only as “The Picture Man”) when a man’s gachoo comes into contact with a woman’s “persimmon seed” (seriously, this is the kind of language Kim uses throughout the series), something magical happens.

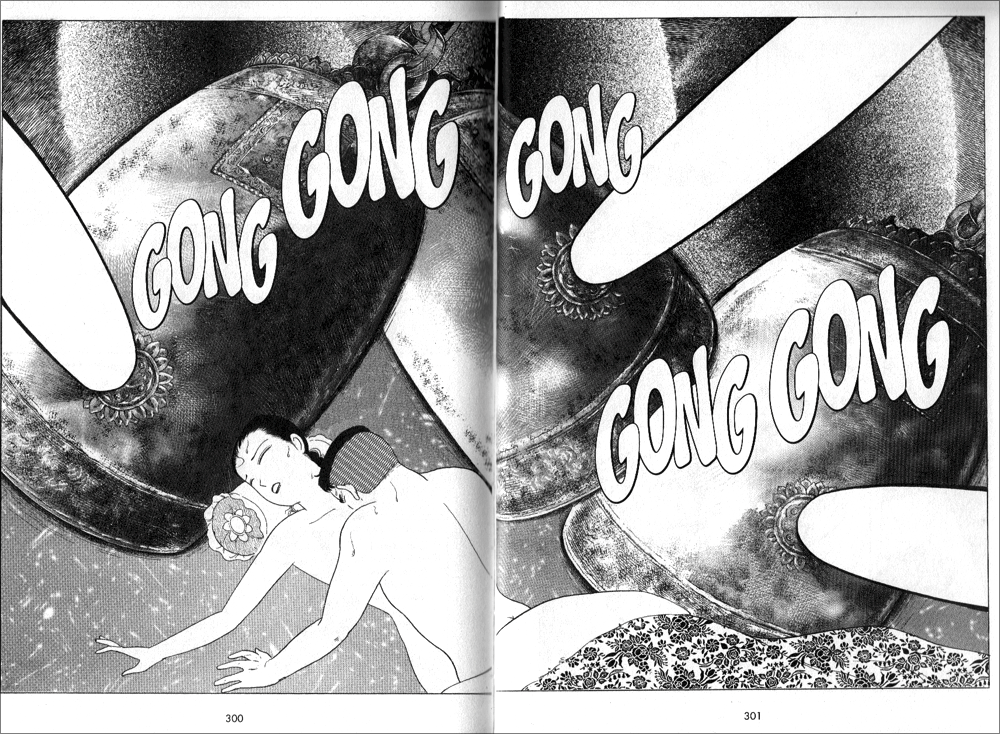

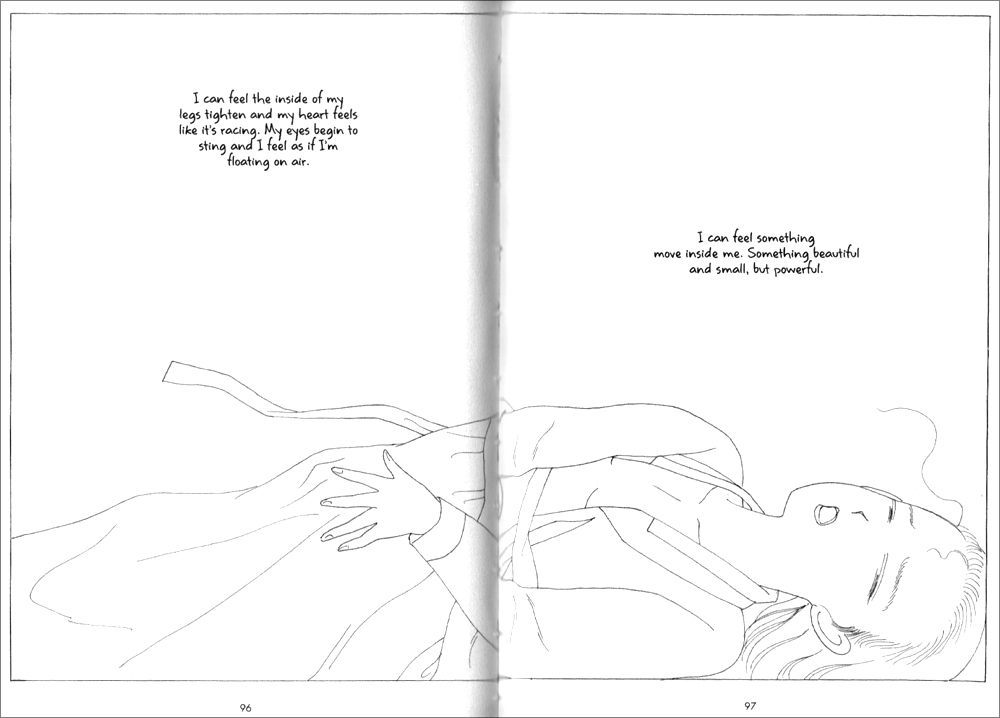

Fortunately, Ehwa gets to experience this magical, floaty, firework-y business for herself at the climax of the book (Get it? “Climax”??), as she’s losing her virginity to her new husband. Though in her case, fireworks and floating on clouds feels more like… a super-phallic bell choir? Mortar and pestle? Um… ?

Though I joke about this being the “climax” of the series, it actually is just a few pages from the end. Ehwa’s journey really does quite literally span the time between discovering penises and getting to be penetrated by one. The entire point of her existence as a character can be summed up this way.

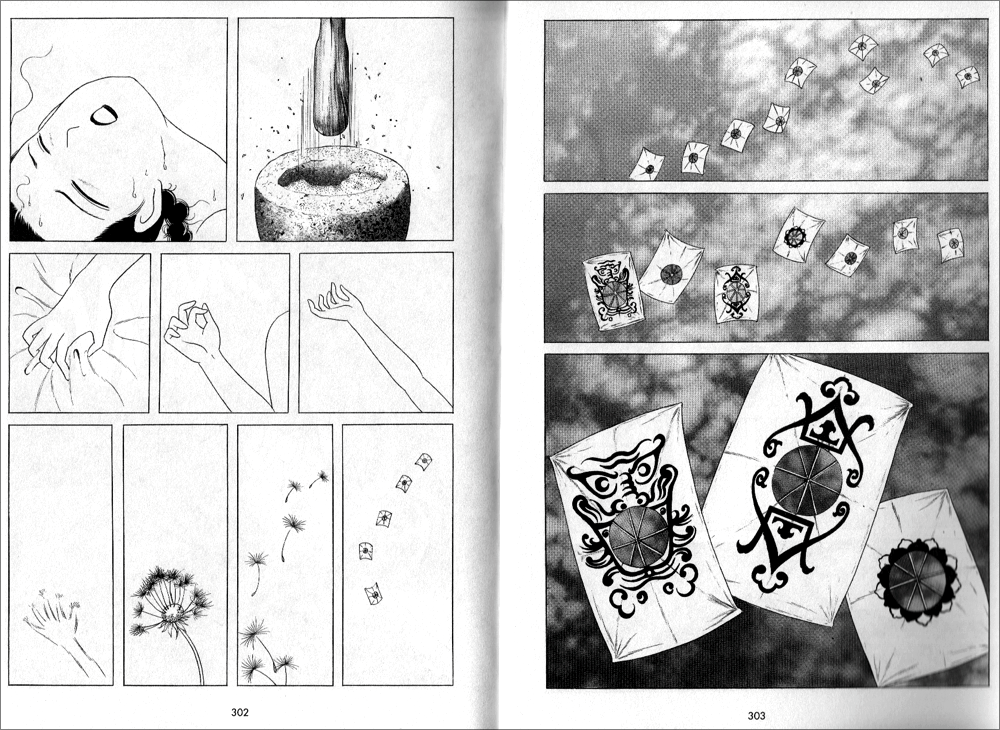

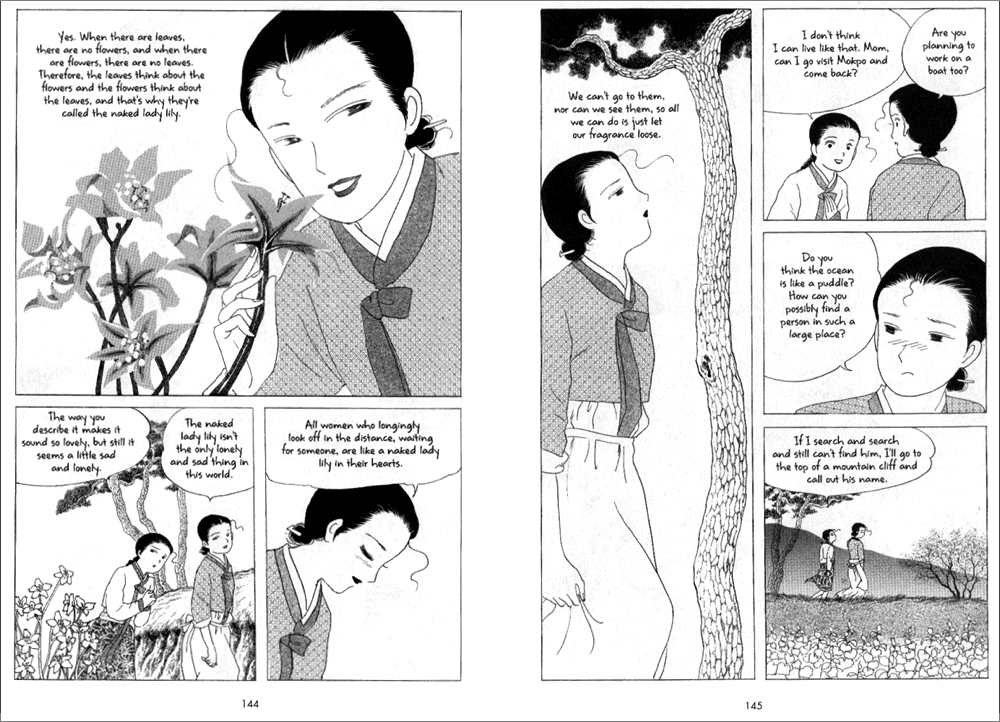

What happens in the middle is largely waiting. Waiting, waiting, waiting. Both Ehwa and her mother fall for wandering men—the kind who spend most of their time traveling for work or simply out of restlessness, but stop in for sex every few months or so. (I once described this type as “… a big, strapping man who values the freedom to wander, is good in a fight, a stallion in the bedroom, and offers questionable financial security. Another male fantasy?”) While this is undoubtedly appropriate to the period and to these women’s circumstances, Kim spends so much time lingering on the wistful beauty of the lonely woman, it begins to feel like a bit of a fetish.

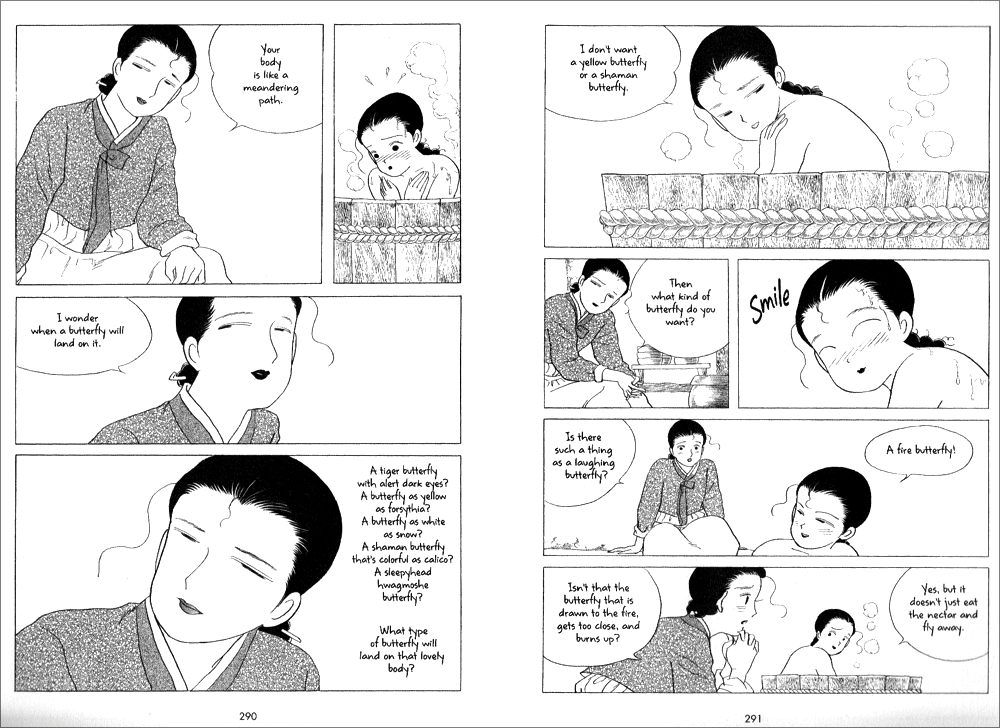

Scenes like this are peppered throughout, along with long-winded discussions in which the lonely, waiting women, the wandering men, and generally everything else of consequence in the story are described as various types of local flora and fauna—to the point that it eventually becomes difficult to remember what or whom all the different flowers, insects, and trees stand for. More than anything else, however, Kim lavishes over the beautiful pain of Ehwa and her mother with genuinely lovely artwork and flowery language worthy of Anne Shirley’s Rollings Reliable Baking Powder story.

But while Kim’s obsession with the feminine loveliness of his characters’ longing reads as simply insulting, his fascination with Ehwa’s burgeoning womanhood borders on downright creepy. Kim is quoted as saying that “the process of a girl becoming a woman is one of the biggest mysteries and wonders of life.” And it’s clear from his portrayal of Ehwa that he considers that process to be entirely sexual. Ehwa has no interests outside of sexual attraction and whatever else is happening with her body—not the tiniest thing. In fact, despite being the only child of a single woman running a tavern all on her own, she doesn’t even seem to have chores to take her mind off her dramatic puberty. Growing up mentally, emotionally, or even just practically seems to be of little consequence to Ehwa or her mother (who remembers just as Ehwa is about to get married that maybe she should teach her how to cook). And while I feel vaguely ashamed for wishing that a female protagonist might take some interest in housekeeping, it at least would give her something to care about besides the long-cherished promise of touching a man’s gachoo.

But while personal interests, hobbies or even standard domestic pursuits appear to be superfluous to “the process of a girl becoming a woman,” the relevant items seem to be:

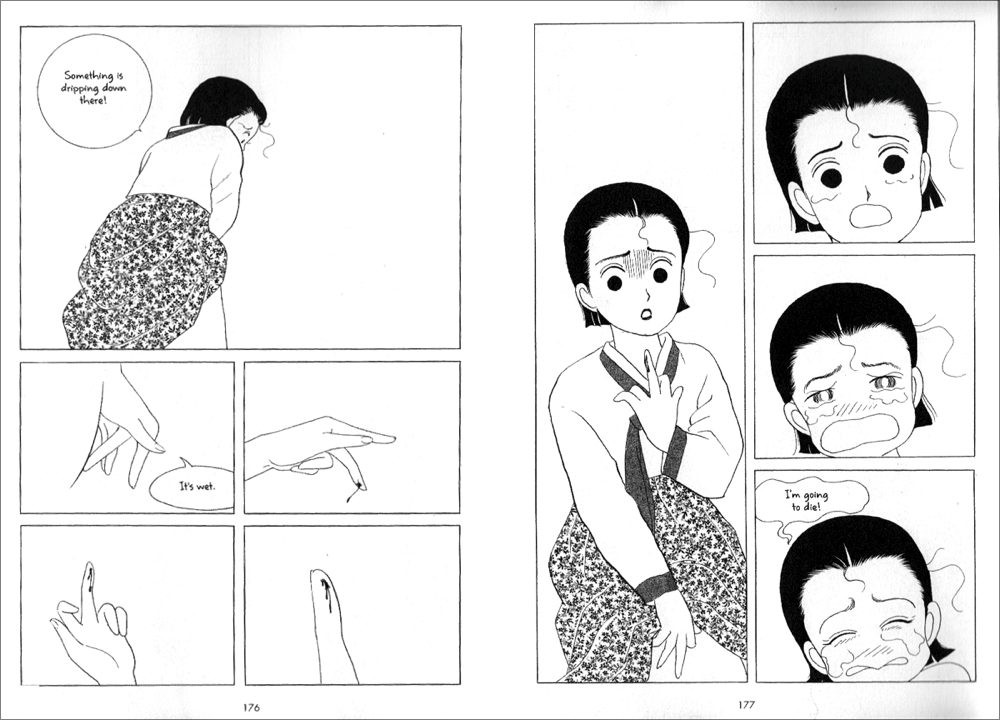

Getting her period.

Learning to masturbate.

And attracting penises butterflies penises.

Yes, Kim Dong Hwa, these truly are the most important aspects of a young girl’s blossoming into womanhood. Thanks for noticing.

Of course, in the end, it’s not Kim’s romanticization of regressive gender roles that really bothers me here, or even his semi-creepy fetishization of womanly “blossoming” (seriously, everything’s got a flower metaphor in this series), not when you get right down to it. I’m a manga fan, after all. I’ve read Black Bird and Hot Gimmick. I survived the first omnibus of Love Hina. I’ve participated in a (not entirely scathing) column on boob manga. What makes me really hate the Color trilogy, is that it’s so widely praised and admired, by male and female readers alike. It is absolutely Serious Business, and that makes it rare fodder for my hatred.

In the books’ endnotes and in Kim’s official bios, he’s referred to repeatedly as a “feminist” writer. He is credited with possessing an “uncanny ability to write from a profoundly feminine perspective.” When, during the Manga Moveable Feast, Michelle Smith and I accused Kim of regarding his female characters’ limited life choices and oppressive environment with “loving nostalgia,” we were criticized in turn for expecting more progressive sexual politics from a period piece. The Color of Earth was published in 2003, yet even Tezuka never treated his (highly questionable) female characters with this kind of rosy condescension.

I tried very hard to like the Color trilogy, but even my most sincere, Pollyanna efforts failed me on this point. In the end, it may be one of the very few comics this midwestern optimist could ever truly hate.

__________

Click here for the Anniversary Index of Hate.

I don’t agree. I understand your critique and I admit that I too was bothered by this work’s exclusive emphasis on sex, but I think that sex is just what this work happens to be about. There are numerous other works in various media that are primarily about the process of male sexual awakening. (An example of this in comics would be Cabanes’s Heartthrobs.) I think that choosing to emphasize sex to the exclusion of other stuff is a legitimate artistic choice, and I don’t think it necessarily implies that sex is the only thing that matters in life.

I guess your argument is that it’s anti-feminist for a man to write about female sexuality in this way. I am potentially receptive to this claim, but I don’t think it’s necessarily true. I think it’s possible to write sensitively about a subject position that you don’t yourself occupy, and I think Kim does that fairly effectively.

These are more vile than Hot Gimmick?

Having looked at the Manga Movable Feast comment, I think Melinda and Michelle do a better job of critiquing this work’s sexual politics. The claim about “loving nostalgia” (or “restorative nostalgia” as Svetlana Boym calls it) is certainly valid. Though again, I would point out that there are lots of notable works of art that look at the past through rose-colored glasses. I think some of the things you’re complaining about are deliberate artistic choices on Kim’s part.

Furthermore, I think this is such a beautiful book that I’m willing to appreciate it despite an awareness of its potentially flawed politics. Maybe this is because unlike all of you, I really enjoyed the poetic language and flowery art.

” There are numerous other works in various media that are primarily about the process of male sexual awakening. ”

This is true…and many of them are really godawful…or at the very least have raise serious questions along the lines that Melinda does here. Chester Brown’s Paying For It, for example…or David Heatley’s My Sexual History. Both focus on sex to the exclusion of other topics…and both tend to make it seem like sex is all that matters, and that women are little more than convenient receptacles/orgasm aids for the protagonists.

It’s be kind of interesting/counter-intuitive to see a women’s sexual coming of age story where the men were used in the way male sexual coming of age stories use women. It doesn’t sound like that’s what this does, though.

Woo boy. They sent me the first volume of this as a review copy and I hated it. I am so thankful I did not see the rest of the volumes as those excerpts are awful.

As for the “poetic language”… I guess if poetic means overwrought with cheesy metaphors…

michael –

“These are more vile than Hot Gimmick?”

I don’t think anything could be more vile than Hot Gimmick.

@Michael “These are more vile than Hot Gimmick?”

Just to be clear, I’m definitely not making that claim. I’m saying that I hate these more, but that’s a completely different matter.

@Aaron Before I decided to write this article, I did consider whether I really had anything new to say about it that I hadn’t already talked to death in my discussion with Michelle. If nothing else, I decided that it would feel freeing to have the opportunity to express my hatred for these books without the responsibility of being the MMF host weighing down on me the whole time. With that in mind, perhaps you can understand why this essay includes less careful criticism and more simple disgust over the ways in which the books offend me on a personal level. Yes, these are Kim’s choices as an artist. I simply hate these choices. It’s a relief to finally say so.

Pingback: Manga Bookshelf | Dabbling in Hate

I remembered renting the first book from the library, expecting something worthy of high critical praise, but then I was confused when it had more dick jokes than Dr. Slump had poop jokes (but Dr. Slump is upfront about it revels in the crazy). I don’t even remember if I finished it, but I returned it, rather upset

I haven’t read this book so I can’t say either way about how obsessed with dicks it is. But Korea is as patriarchal a society as it gets. Even in the 21st century, women are pretty much there to make men’s lives more enjoyable. You can find some ladies who don’t fall into this, but a woman’s value is pretty much measured by the penises in her life. And yeah, all the guys are obsessed with their dicks and everyone else’s from an early age.

The “Hooray for dicks!” motif is just the culture filtering through the comic much in the same way violent power fantasies filter through American books.

But…other Korean comics aren’t like that. Dokebi Bride for example…there are some dick jokes, but the book certainly doesn’t present the protagonist as defined by men or penises.

I suppose an example of a similarly sex-obsessed work written by a woman would be Colleen Coover’s Small Favors.

I think what William George wrote can be true in some respects but is also an over-generalization. You can see some masochistic impulses and presumably “endearing” chauvinistic behavior quite regularly in hugely popular K Dramas made for women. But just like in Western romances (?), men are also regularly put down and made fun of.

Aren’t the demons in Dokebi Bride meant as stand-ins for men?

I only know what I experienced living in South Korea for seven years. Sorry.

Pingback: MangaBlog — Let’s read manga!

@William George, I know a number of South Koreans who I think might take issue with that generalization, but even if it was so, it’s not something I’ve recognized in translated manhwa as a whole. In fact, I’ve often commented that one of the things I tend to appreciate in sunjeong manhwa (at least what we’ve seen over here) is that the heroines tend to be really idiosyncratic and kind of kick-ass–more so than is typical of translated shoujo manga. Even though these are usually romances, the girls have their own career plans, family lives, and personal interests outside the obligatory love story, and you rarely get the sense that they need a man to become whole people.

In the series 13th Boy, for example (a favorite of mine), though the heroine, Hee-So, is absolutely obsessed with her love life (the title references the number of boyfriends she’s had over the course of her pre-adolescent and teen years), she is so fully her own person, it is impossible to reconcile her with what you describe. And she spends a lot of her time in the company of her (female) best friend Nam-Joo, a judo champion whose martial arts ambitions far outweigh any interest she might have in boys.

If even stories like these, which are typically focused on heterosexual romance, routinely produce more well-rounded female leads than the Color trilogy, it’s hard for me to accept the premise that Kim’s work is an inevitable product of South Korean patriarchy. And I certainly can’t accept him as a “feminist” writer in that context.

I guess the point is…I don’t really have any doubt that Korean society is sexist. I mean, we’re sexist, why shouldn’t they be? And I’m also sure that the Color Trilogy reflects or is influenced by that sexism. But cultural products aren’t algorithms; creators take their culture and think about it and translate it in various ways. Surely, everyone in Korea isn’t equally unthinkingly sexist — and every comic produced in Korea isn’t equally unthinkingly sexist.

http://www.southparkstudios.com/clips/152121/a-redwood-forest-of-penises

“I know a number of South Koreans who I think might take issue with that generalization…”

I feel defensive when people point out my perfectly spherical beer belly. It runs counter to my self image as a slightly balder, sexy and dynamic Han Solo. Humans, hey?

“…creators take their culture and think about it and translate it in various ways…”

Certainly. Yet it’s still a product of that culture be it a reflection of it or a rejection of it. From all reports, this comic fits in the “reflection” category.

I can see it as one possible reflection. But no culture is monolithic…and no culture is completely isolated. The tropes Melinda identifies in the Color Trilogy are tropes which very much exist in our culture, which is not unphallocentric itself. The things Melinda dislikes are things she recognizes.

I don’t know that you’d disagree with that. I mean, you’re not saying that South Korea is uniquely, monolithically sexist, right? If all you’re saying is that the attitudes in the comic are ones that are familiar to you from South Korean culture, then we’re probably not arguing about anything, really….

I think what William is saying is that South Korean society is noted to be remarkably chauvinistic (sexist, whatever) even among chauvinistic Asian societies (like that which I live in for example). This is the country which invented useful terms like “honey thighs” and “bagel girl” to describe the actresses/idols of the day.

It’s a stereotype which I’ve heard repeated on several occasions. He seems to be saying that this stereotype is true. I suppose his years in South Korea do carry some weight. I’m not entirely convinced but maybe I’ve just interacted with the wrong South Koreans.

” I’m not entirely convinced…”

I don’t plan to try to convince you. Both of our lives are too short.

” If all you’re saying is that the attitudes in the comic are ones that are familiar to you from South Korean culture, then we’re probably not arguing about anything, really….”

You’re right. We’re not.

William, I’m unclear why you feel the need to get huffy? It’s really not clear what you think you’re saying, and when asked politely to clarify, you seem to just get more and more snarky. But…I guess if that’s where you’re at, it’s where you’re at. Thanks for stopping by.

I’ve only tried reading the first volume of this, having borrowed it from a library and never made it to the end. The flowery language and the art were both so boring (and I love Heian poetry and diaries, so it’s not like I hate flowery expressions in general). I couldn’t understand why all the critics were showering praise on it. I normally love shojo manga and its Korean equivalent, but just couldn’t bring myself to keep reading. Thanks to your review, I’m happy I did not waste more time on it.