“From the very first, children are at one in thinking that babies must be born through the bowel; they must make their appearance like lumps of faeces.” That’s Freud from his Introductory Lectures. I found the quote in an essay by John Rieder called ” Frankenstein’s Dream Patriarchal Fantasy and the Fecal Child in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and its Adaptations”. Like the title says, Rieder’s essay argues that the Frankenstein monster can be seen as a fecal child — literally, a piece of crap. Mary Shelley’s book is an elaboration and/or a critique of a patriarchal fantasy in which men dispense with women, creating fragrant, mottled life from their own blessedly demonic bowels.

Frankenstein doesn’t much like his shit baby — but that’s just another sign that he’s a weirdo. Most kids — boys and girls — like their poop. Or as Rieder explains:

When Jehovah looks at his handiwork he sees that it is good, and Freud tells us that children at the stage of development in question are far from feeling disgust at their own feces. On the contrary, they take pleasure in manipulating them and are apt to express pride and affection for these “children.”

Rieder goes on to suggest that it is normal for adults to express disgust at fecal creation — but is that really the case? Fecal children — those Frankenstein monsters — are, after all, readily analogized to that other marvel of sterile birth, artistic production. If Frankenstein’s monster is his poop, it is also his art — and who among us of whatever gender has not glowed proudly at our own glorious, smelly glob of suchness? Who has not grabbed friends and relations alike, hauled them to the glowing receptacle, lifted the lid and declaimed with pride, “Look what came out of me!”

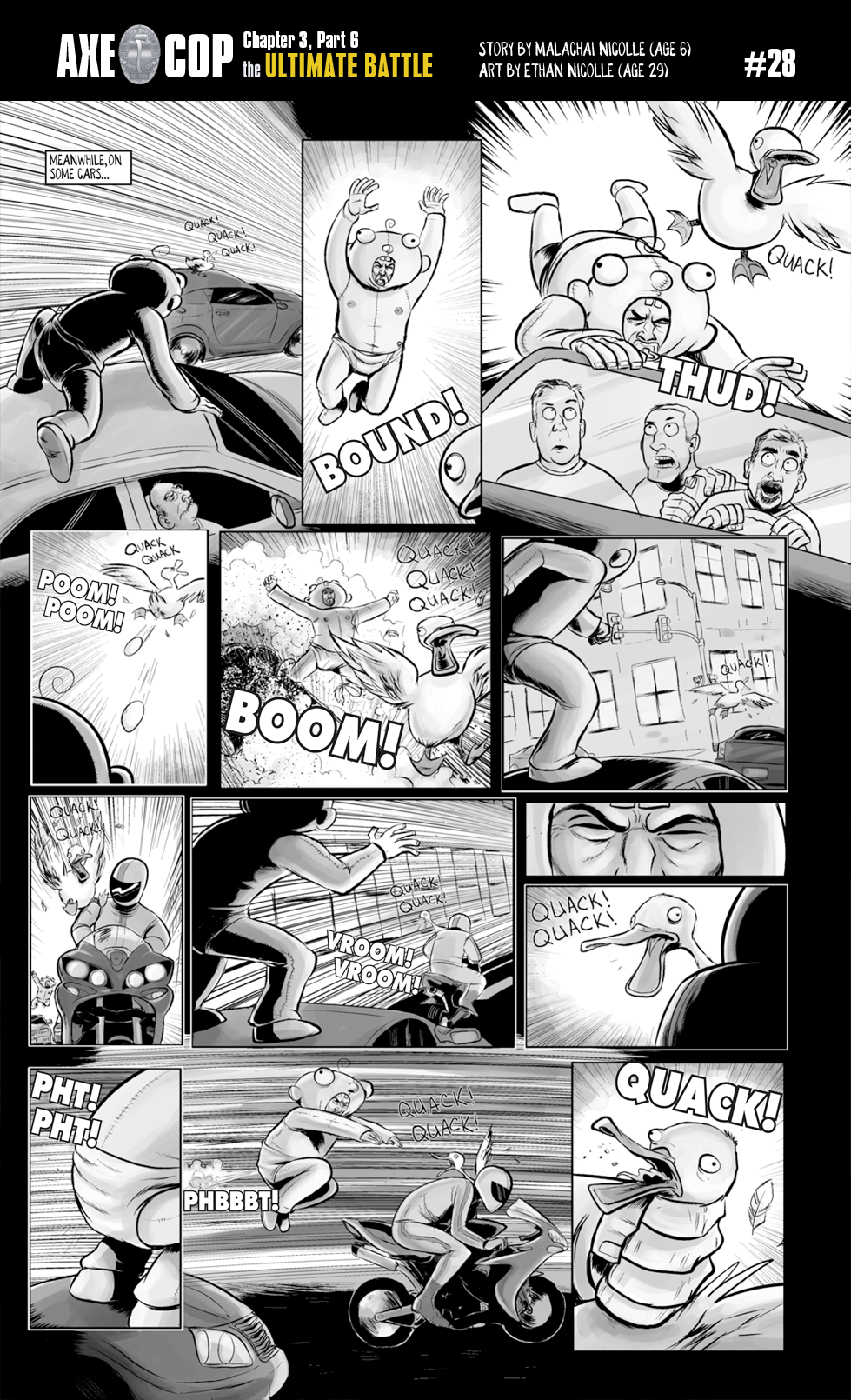

If you are looking for gratuitously giddy anal celebration, you cannot possibly do more gratuitous nor more giddy than the amazing Axe Cop adventure, “The Ultimate Battle,” reprinted in the first Axe Cop trade. Axe Cop is a web comic phenomena drawn by artist Ethan Nicolle and written by his (then) 5-year-old brother, Malachai (or Micah.) Like most kids, Micah is a lot less chary of indulging his fecal obsessions than his adult peers, and “The Ultimate Battle” could not be much more frank in its fascination with what comes out of our bottoms. One of the comics best set-pieces involves Babyman (and yes, that’s a grown man dressed in a baby outfit), who flies by passing gas, chasing a duck which shoots exploding eggs out of its rear.

Later, Babyman and a young similarly dressed ally (Babyman Jr.?) chase a giant monster made of sentient candy who excretes tiny cars which grow into big cars and then when people try to drive away with them they explode. And, finally, a whole team of Babymen chase a giant egg with feet which poops out phones that ring and then people answer them and…well, you can probably figure out what happens next.

But if you think grown men dressed as babies dodging exploding poop is some bizarre Oedipal scatology…well, you ain’t seen nothing yet. The climax of the story involves the evil Dr. Doo Doo, a giant sentient piece of poop with a gaping mouth and a monocle. When he shouts “Poooooooh!” Micah says, “instantly everyone in London has an accident in their pants.”

The turds they poop turn into evil human-sized turds armed with swords, each of which quickly murders its progenitor, setting the stage for an ultimate battle between superheroes, ninja moon warriors, and good-guy zombies on the one hand and evil sentient poop on the other.

Obviously, an ultimate battle between superheroes, ninjas, zombies and poop stands on its own merits. But the diabolically summoned/involuntarily produced sentient turds which kill their father-mothers and take their places also works as a nice analog for Micah’s own precocious, volcanically natural artifice, which revels in conquering/befouling the world all the more joyously because he’s not even trying. Even Dr. Doo Doo’s poop command seems to mirror the collaboration between the brothers Ethan. Micah, says, “pooh!” and Ethan miraculously creates pooh by the buttload.

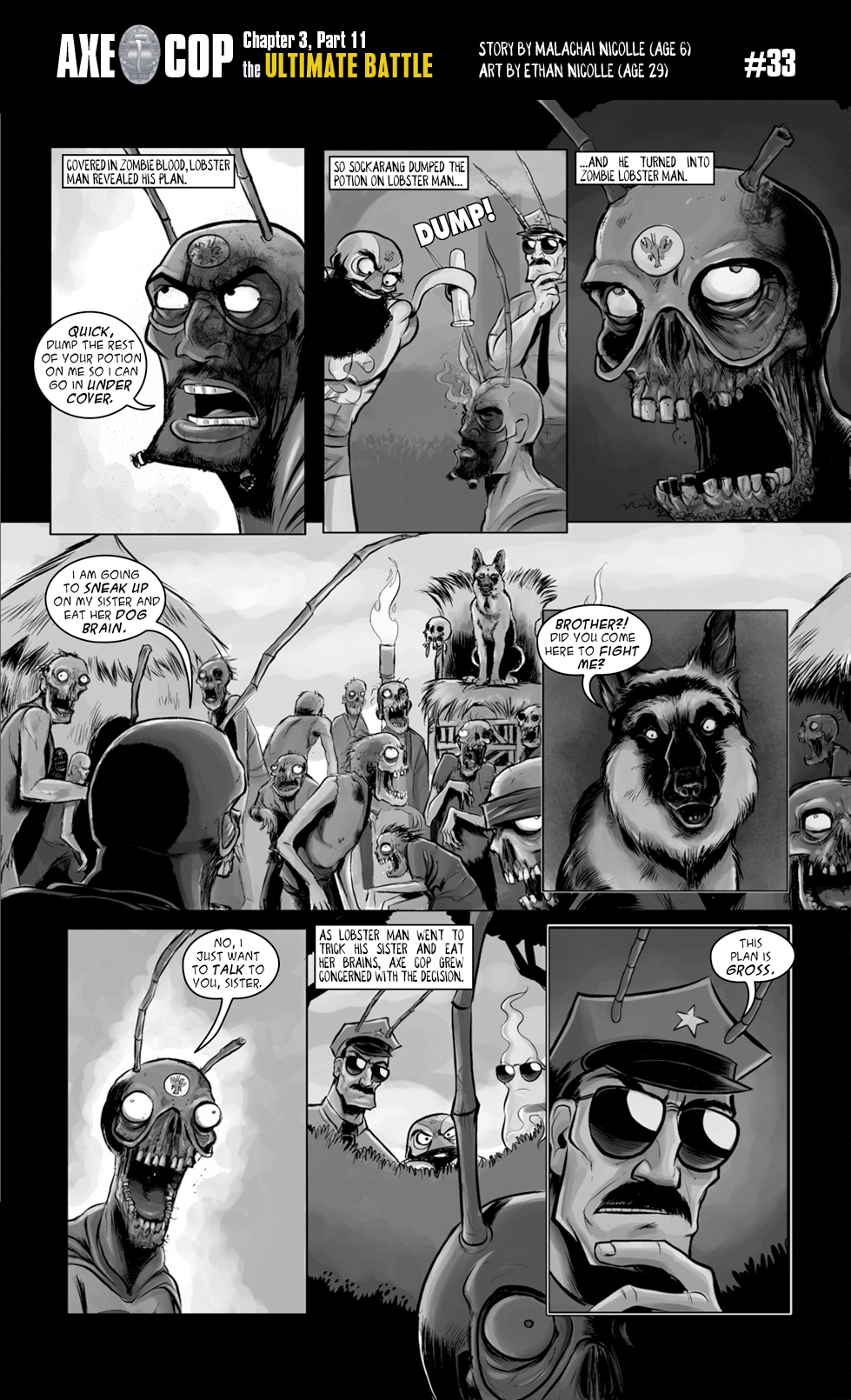

Not everything in Axe Cop is pooh-based — but everything does have that magical sense of being hauled out of the creators’ asses. People in Micah’s world are constantly transforming and morphing from good to bad or from dinosaurs to dragons or from unicorns to dinosaurs to dragons to cops or from weird hybrid thingees to other weird hybrid thingees. This trope reaches a quintessence of preposterousness in a sequence where Lobster Man (who we learn later used to be part dog) rubs his face in zombie blood so he can turn into a zombie. Then he gets his companions to dump good zombie potion on him so that he can go undercover with the zombies and eat his evil zombie sister’s dog brain.

In a world where creation is as easy as pooping, it makes sense that each self should excrete a new self like the phoenix springing newborn from its own bowels. Reality is a mushy mass to be formed and reformed, sculpted, smeared and flung in a gloriously manipulable mass.

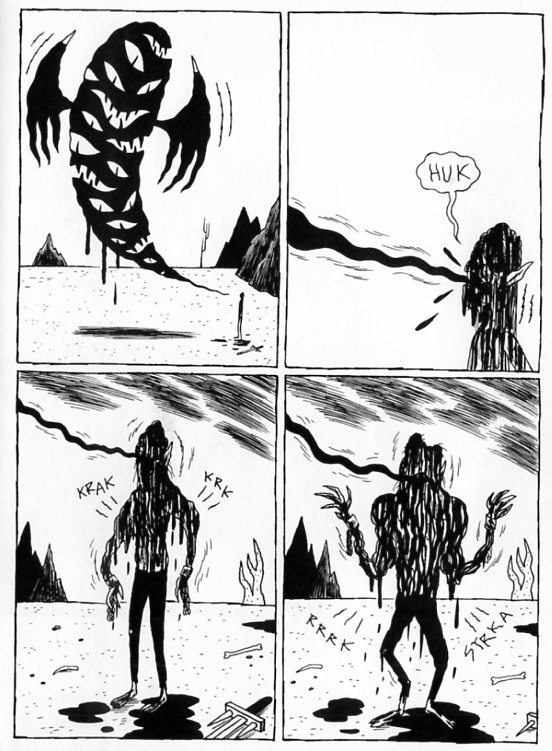

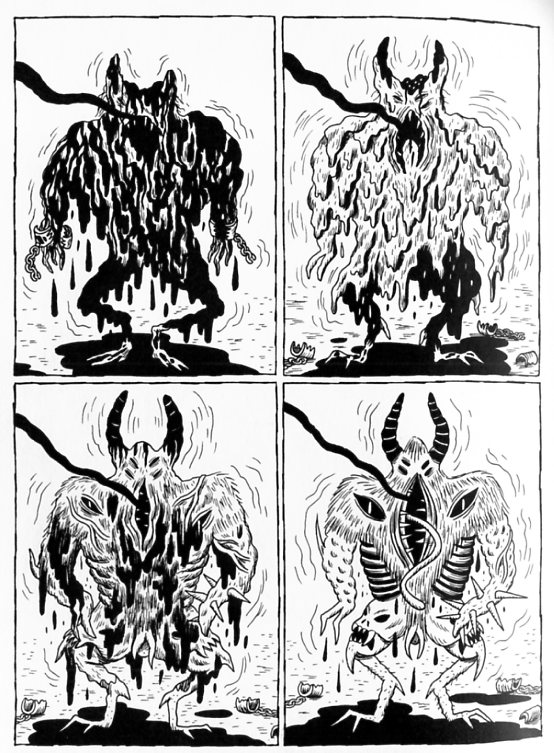

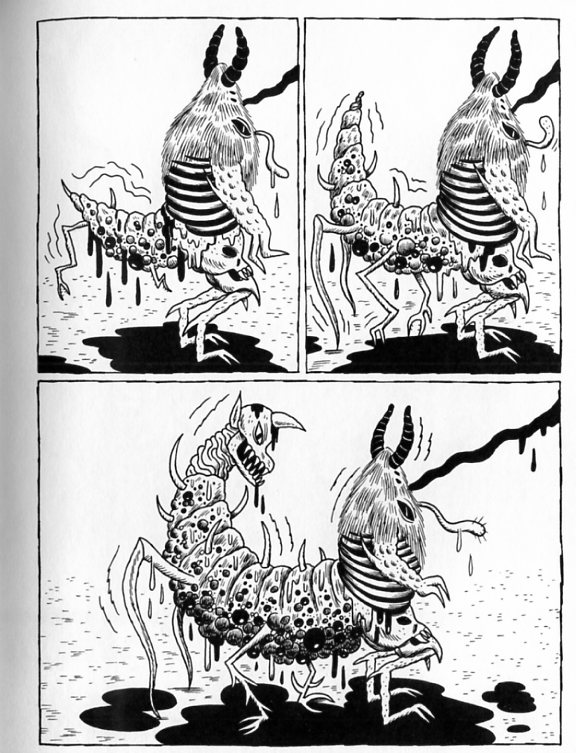

Which is why the artist that Micah reminds me most of is Johnny Ryan. Where Axe Cop’s drawing is cartoony and clean, though, Ryan (as the above image shows) embraces the messiness of his scatological obsessions, As I said in an earlier post:

In Prison Pit each body is a busted toilet whose stagnant water births some mangled abortion dragging its placenta over the edge of the porcelain to flop wetly on the cold tiles. Tentacles erupt from vaginas, vomit spews from sentient arms, and dripping things that should not be tear open their mothers in an orgy of violent polymorphous ichor. Black blood drips like ink off the mechanical penis of Ryan’s protagonist and then pools in scratchy pen lines, half-formed half-assed nightmares drawn on the back of a middle-schooler’s history notebook.

Aligning Johnny Ryan and Micah Nicolle complicates them both, I think. If Ryan is like Nicolle, then he’s not just a simple shock jock” — and if Nicolle is like Ryan, then he’s not, perhaps, quite as innocent as we like to imagine 5-year-olds as being. Frankenstein building that monster — like Mary Shelley writing that book — is both an exuberant wallowing in the glorious Godhead and an ugly stain upon the divine prerogative. If the creation of art makes us human, then we are our own foul progeny — monster Babymen sculpting monster Babymen, like diapered Frankensteins.

I don’t know, Noah, I still don’t buy it. (I’m commenting still having not read Prison Pit, so take that for what it’s worth – I might just be revealing my ignorance.)

Malachai is a little kid with a little kid’s imagination. I don’t really put much stock in Freud, but I will certainly agree with you that Malachai is being as transgressive as he knows how to be. Ethan’s story about Malachai leaning over and devilishly whispering his plans for a poop-themed villain confirm that.

There are a few places where I think the comparison between Malachai and Johnny Ryan falls apart, though. First, Malachai is a mediated creator, at best. His stories filtered through the artistic and editing sensibilities of his brother, who is hardly an impartial vehicle for storytelling. If I remember right, the Babyman arc was mostly Ethan’s idea.

Secondly, and I know this is a matter of personal taste, much of the charm of Axe Cop comes from the fact that Malachai doesn’t realize that what he’s doing is funny. He’s trying to tell a cool story. That charm is nonexistent in Ryan’s comics, which are transgressive in a way that’s meant to offend and hurt.

I don’t think the cartoon version of Axe Cop works (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Fkh6IZdPp98) because it’s too self-aware. I don’t think Johnny Ryan comics are in any way comparable either. I think if you had to compare a comic written by an adult to Axe Cop, Fletcher Hanks would be a better choice.

Fletcher Hanks is nothing like Malachi’s stuff. Hanks is ideologically committed to fascist vigilante politics. That’s really not what’s happening in Michah’s work, and not what’s happening in Johnny’s.

It’s telling I think that you go for Hanks, though. You’re basically arguing that Michah is an outsider artist. There is certainly a tradition of lumping kids in with the insane in outsider art, so that’s not unprecedented. I don’t think it works well for Micah though — and I’m very leery of the position you seem to be heading towards, where Micah’s outsider status is the sole validation for his art.

Axe Cop is extremely invested in pop culture and genre narrative. It’s about spinning out creativity, not about putting over a particular ideological view. It’s scatologically obsessed, ADD, genre mash up goofiness, which is intended to be transgressive and fun and funny. (Ethan talks about Micah laughing at his creations. If you don’t think he thinks that stuff is funny, you’ve never talked to an eight year old.)

Your effort to distinguish Micah and Johnny really seems to come down pretty much entirely to intentionality. Specifically, you think Micah doesn’t understand the implications of his art, therefore you like it better. That seems like some really shaky ground to be crawling out onto, to me. In the first place, it seems condescending. In the second, I mean — what about the scatology? (Which is not in Hanks?) What about the violence? What about the bizarre body transformations (not in Hanks either)? Are you really contending that you’re not allowed to make that sort of thing up and have fun doing it once you go through puberty? That just doesn’t make any sense at all to me.

Finally, I’m not really sure why it’s a contradiction to what I’m saying to point out Ethan’s involvement? He did I think suggest the Babyman sequence initially — but that just shows that adults can enjoy scatology and babies and stuff flying out of butts too, which hardly looks like a contradiction of my argument that Johnny is doing something similar? I think either you misunderstood me or I’m misunderstanding you…?

Maybe repeating myself, but…as the father of a kid about Micah’s age, I think it’s worth pointing out that kids don’t tell stories that much differently than adults, necessarily. Or at least, these kinds of stories, with lots of events and violence and silly transgression and references to genre — there isn’t any kind of firewall between how kids think about that stuff and how adults do. Kids know less, and can be really creative and funny and make odd leaps, but they really aren’t outside those narratives, or coming at them from a place that’s incredibly different than adults. Really, my son thinks farting is funny for exactly the same reason an 18 year old or an 80 year old would think farting is funny.

I think Hanks can be a lot like Malachai’s stuff! Don’t you think so? Axe Cop, especially early Axe Cop, is full of Malachai’s creative methods of killing evildoers. And the dialogue/narration reads quite a bit like Stardust. That’s what invited the Hanks comparison, not the outsider art aspect. I certainly don’t think it’s the sole validation for his art, but I did think it’s an obvious comparison.

There’s a distinction to be made, I think, between the “ages” of Axe Cop. Early Axe Cop is not obviously intended to be funny, as much as it is a transcript of Malachai’s play-stories. Newer Axe Cop is more self-aware, I think. But I stand by the idea that Malachai was originally more invested in telling a “cool” story than a funny one, and I think the existence of the “funny episode” (http://axecop.com/index.php/acepisodes/read/episode_99/) lends some credence to that idea.

My pointing out Ethan’s involvement was to make a distinction between Johnny Ryan’s stream of consciousness gross-out stuff, and the more calculated re-telling of little kid stories that Ethan does. Ethan’s great achievement is making Malachai’s stories readable without getting tiresome or losing the personalities of the characters Malachai created and cares about. There is no one-to-one comparison between Malachai and Johnny Ryan because Ethan mediated Malachai, that’s all I’m saying.

I guess this is what my distinction comes down to: Malachai’s stories are transgressive, but ultimately playful. Johnny Ryan’s stories are transgressive, sure, and seem just as energetic and whatever, but are much more deliberately hurtful. Malachai doesn’t make stories in order to offend like Ryan does – if Ryan’s comics were all about farting or “head chopping,” then I might buy your comparison more. But as it is, I can’t see the comparison because the intent and the result are very different. There is something to be said, too, about a child’s ability to understand the concept of killing/torture/whatever versus an adult’s.

The Prison Pit art looks alot like Gilbert Hernandez. Trying to ruin it for you, Noah.

A worthwhile undertaking…

The Prison Pit art is a bit like Gilbert. Also influenced by manga though, pretty clearly. He’s a lot more inventive/dramatic with layout than Gilbert is, I think.

Ethan definitely has an editing/curating/narrating function…but Johnny just does those things himself, pretty much, it seems to me. I don’t see the process being that much of a difference in terms of judging final outcomes. (I also think Johnny’s art is a lot more interesting than Ethan’s, especially in Prison Pit. Again, his layout is much better; his character designs are a good bit more inventive;he plays with the flatness and drawingness of the art in a way Ethan very rarely does. In part it’s just about how slick you like your art, I guess — but I find Johnny’s a lot more fun/evocative.)

Jacob, you’re sort of scooting around, but you’re still basically saying it’s a matter of intentionality. Johnny’s older, so yes, his transgression is more clearly transgressive to an older person. But the interests and fascinations — scat, fluids, violence, pulp, body transformation, and (very much for both) video games — are the same for both. I think you’re downplaying the extent to which Ryan is about the rush of creativity — and downplaying the extent to which little kids’fascination with violence and trasngression is continuous with, rather than radically different from, adult’s fascination with violence and transgression. That’s why Malachi’s work is meaningful to me. Not because it’s outside how I process the world, but because it makes sense to me — to my sense of what’s funny and exciting and weird, and violent and transgressive and, yes, even sadistic as well.

I should read Prison Pit before I argue anymore because what you’re saying seems reasonable. I shouldn’t conflate Angry Youth Johnny Ryan with Prison Pit Johnny Ryan when I don’t really know much about the latter. Otherwise I’ll just keep scooting, haha. This is where analytical Jacob meets emotional Jacob; just because I don’t like Johnny Ryan very much doesn’t mean you’re wrong.

For the record, though, I stand by my Fletcher Hanks/Malachai comparison. People turn into other things all the time in Fletcher hanks! Rats, giant heads, you name it.

Hmmm. I need to look at Hanks again. The poop and the sense of creative ADD isn’t there, I don’t think, but I’d agree there is a similar goofy sadism in the administration of justice — and possibly some of the transformation. It actually makes sense with Johnny Ryan too, now that I think about it; again, it’s the sadism/adolescent power fantasy pushed to a ridiculous extreme.

Which also makes Johnny somewhat like Steve Ditko, which I bet he really wouldn’t like…if that’s any comfort. (But Prison Pit is in fact somewhat different than AYC…though not so much that I don’t think that AYC is a good bit like Axe Cop too.)

Domingos, I’m assuming you’re saying it’s worthwhile for Eric to ruin it for me, right? You can’t possibly be saying that Johnny Ryan or Axe Cop is worthwhile — that would really screw with my paradigms….

ew

The former, of course.

“The former, of course. ”

Phew. I was worried there for a second…

Actually I like that cute monster above with the eyes and the mouths.

Actually, what those Prison Pit pages remind me of is Jim Woodring. It’s the same sort of lovingly rendered bizarre metamorphosis.

Domingos, is it the sentient poop drawing you like? It is pretty engaging….

THANK GOD, OBAMA WON!!!

(Just had to get that out of the way; yeah, plenty to attack him for, but compared to the Romney team…)

————————

Jacob C. says:

…There are a few places where I think the comparison between Malachai and Johnny Ryan falls apart, though.

————————-

Yeah; for instance, I hope Ryan’s smarter than a 5-year-old!

————————-

..That charm is nonexistent in Ryan’s comics, which are transgressive in a way that’s meant to offend and hurt.

————————-

Very much so. There’s also the delightful, dream-like freedom of imagination at work in Malachi’s stories…

————————–

Noah Berlatsky says:

Fletcher Hanks is nothing like Malachi’s stuff. Hanks is ideologically committed to fascist vigilante politics. That’s really not what’s happening in Michah’s work, and not what’s happening in Johnny’s.

—————————

Certainly not; but Jacob didn’t specify which particular factor he found similar.

A clear similarity — though the tone is dead serious in Hanks, exuberantly innocent (as far as kids are, anyway) in Micah — is the surreality, stream-of-consciousness narrative.

————————–

Martin Wisse says:

Actually, what those Prison Pit pages remind me of is Jim Woodring. It’s the same sort of lovingly rendered bizarre metamorphosis.

—————————

True, that’s there. There’s also a pretty huge amount of more gruesome metamorphosizing going on in manga and anime; much of it clearly inspired by Rob Bottin’s brilliant, groundbreaking FX work in the John Carpenter film of “The Thing.”

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lfdRTvytNvY

(Look, kids, no computers!)