Women are beaten time and time again into submission, but they always return, or if one women is eliminated, another takes her place. Whatever it is these women stand for, men and their phallicism are fairly powerless in its presence.”

—Anne Allison, Permitted and Prohibited Desires: Mothers, Comics, and Censorship in Japan

Allison in the above quote is referring specifically to Japanese erotic manga of the 1980s and 90s, but her point certainly fits Junji Ito’s horror manga as well. Indeed, Allison’s quote is basically the plot of every one of Ito’s Tomie stories. In the first of these, “Tomie”, from 1987, the titular heroine, a bewitching high school girl, comes on to her teacher, Mr. Takagi, on a school trip. Another student confronts her, and in the scuffle she falls off a cliff and dies. Takagi then orders all the boys to take off their clothes and cut her body into pieces while the girls look out and make sure no one interferes. The boys then dispose of the pieces of her body. Shortly thereafter, though, Tomie miraculously reappears at school — causing several of her murderers to lose their minds.

This is the prototype for all of the Tomie stories. Tomie, it turns out, is a cancerous monster. Her beauty corrupts men, who love her and then attack her, chopping her into bits. Each piece then regenerates (more or less gruesomely) into a new Tomie. As Allison says, Tomie is always murdered and diced and always returns.

In her book, Allison argues that Japanese families during the 1980s and 1990s were strongly matriarchal. Men worked long hours and traveled even longer hours to work; as a result they were effectively absent from the home. Women were in charge of shepherding children through the complicated and rigorous Japanese school testing regime. The mother-son bond then was supposed to function as a lever to propel children into their place in Japan’s resurgent advanced capitalist society. Rather than an Oedipal dynamic, in which boys symbolically reject the mother to join the world of the father, Allison suggests that in Japan boys see mothers as symbolic of the (still very patriarchal) culture. Resentment against hierarchy and limits often manifests not as competition with men, but rather as resentment against women. Allison argues:

The real stress in all this might be less on teh breakage and more on the display: the show of aggression used as a device to ensure the continuity ofa relationship rather than to sever it…. Such “devices” are found in mother-child relations in Japan, where children are indulged in a degree of aggressiveness (hitting, slapping) against their mothers….

Again, it’s not hard to see how this maps onto Ito’s Tomie stories. Tomie is the constant target of sexual and physical aggression — and of physical aggression as sexual aggression. But all of that aggression is her fault; she is the instigator — the uber-feminine manipulating and devouring men.

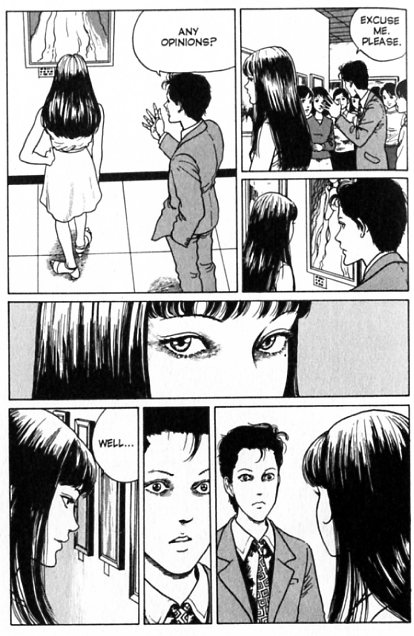

In the ero-manga Allison discusses, men get to dominate women in ways which, while not perhaps entirely convincing (those pesky women keep returning!) are still clearly meant to be provisionally satisfying and empowering. In the Tomie stories, the anxieties are the same, but the outcome is (at least from the standpoint of the male ego) significantly bleaker. In “Painter”, for example, the erotic male gaze — surely a major site of aspirational male empowerment and dominance in ero manga — is brutally and explicitly reversed.

The painter has created a series of portraits of his girlfriend; by gazing at her and commodifying her, he has attained fame, fortune, and dominance. One look from Tomie, though, and that gaze is flipped; suddenly it is not him who has the commodity, but the commodity who has him. At her hypnotic instigation, he jettisons his former model and becomes obsessed with capturing Tomie’s beauty on canvas. He tries and tries and tries, but Tomie — like the education mother, both inspiration and task master — taunts him with his failure. Finally, he succeeds:

What he has captured is, precisely, an image of the commodity — Tomie as bifurcating product — as monstrous excess thing. Woman’s biological reproduction is conflated with capitalism’s artificial reproductive parthenogenesis. The feminine is nightmare proliferation; the object that subjects the gaze.

Reversing the gaze is often seen as a feminist move; a way to turn the patriarchy’s weapons against it. Tomie does certainly enjoy her power over men (at least the bits of her power that don’t involve her being chopped up into bits.) But overall, the feminine/capitalist uber-mommy isn’t exactly envisioned by Ito as empowering for women. When Tomie’s kidney is implanted in another women, for example, the other woman turns inevitably into Tomie. And another girl who encounters Tomie eventually ends up like this.

Women’s power for Ito, then, isn’t something that women themselves control. Rather, it explodes from inside of them, distorting their flesh and sending their severed gobbets across the landscape. Female-as-symbol is constantly bursting out of female-as-body, leaving behind a gaping corpse in the shape of a vagina dentata.

That maw is not so much women as feminized capitalism, a beautiful endlessly proliferating fissure. In one of the stories here, Tomie is a high school’s ethics officer, and that seems oddly apropos. She circulates, a fungible locus of power which reinscribes the same social roles over and over, men and women all welded into an organic, replicating mass by the remorseless workings of pleasure, image, violence and desire.

What a great reading. Good essay, man. I need to return to Tomie soon.

That Anne Allison book is just so insightful and useful for this stuff. She doesn’t talk about horror manga, but the anxieties she talks about for erotic comics map perfectly.

Really, I think it’s one of the two or three best comics studies books I’ve read. Really fabulous work.

Cool, I’ll check it out.

Noah: But overall, the feminine/capitalist uber-mommy isn’t exactly envisioned by Ito as empowering for women.

But there’s this whole conversion (away from false consciousness) thing you sometimes see in “feminist” stories created by men. I can’t remember where Tomie was first published but I’m pretty certain it was a shoujo horror manga. Japanese girls love this kind of thing (apparently). Hence the kidney transplantee (presumably nice and pliant) being transformed into Tomie is part of the some equation. Tomie is supposed to be a new creed for subjugated Japanese women. The Chinese characters which make up her name read Prosperous/Abundant River.

Something similar happens towards the end of that Korean movie Bedevilled.

Hmm; that’s interesting. There could be some hint of the demure doormat changing into the bitchy vamp, I suppose, and that being exciting/interesting/entertaining for woman.

I’m still awfully skeptical of a feminist reading, though, because:

1. it’s really presented pretty explicitly as gruesome rather than empowering. The monster woman with Tomie heads coming our of her, or the kidney morphing into a face; those are images of monstrosity and horror, not of empowerment.

2. allowing women to switch from virgin to whore isn’t much of a choice

There’s clearly a sense in these stories that women have power…and Allison’s book shows that women do have a kind of power in Japanese society. But it’s a power that’s very much prescribed through/by performing certain (capitalist) tasks in a proscribed way, rather than through (for example) seeking individual fulfillment. Part of Tomie’s “power” remember is to be (implicitly sexually) assaulted and murdered over and over and over again. Even if you’re a doormat to begin with, it’s difficult to see doormat-to-vivisected-assault-victim as a feminist progression.

Yes, but if you’re consistently seen, depicted, and expected to be a giggly, demure sex object, I suppose sometimes you want to scream that there’s a raging monster inside of me. Or maybe that’s what men think some women want to say/scream. The reality is that most girls want to be like Bella Swan and didn’t like her “whoring” around behind Robert Pattinson’s back. So “semi-virginal” is probably the real fantasy. Then again, the kind of girl who likes Ito or Umezu Kazuo is probably not your typical kind of Japanese girl.

I haven’t read Tomie in years (and certainly not to its conclusion), but couldn’t her constant murder and assault be a reflection of what women have been forced to endure through the various wars, in Japanese pornography (which is fixated on assault), and in society in general? I thought you liked the rape-revenge genre.

The metaphorical linkage between water and women in his stories (see also Uzumaki) also bears examination. Read any interviews with Ito about his relationship with women (healthy or phobic)?

The problem is that you’re not ever placed in a position of sympathizing with her. The murders are clearly marked, always, as her fault; she creates the desire both for sex and for violence. And her real self, her true self, shown through photos and painting, is always monstrous, deformed, and evil.

The take on gender is interesting, and complicated enough that I think you can read against it. I can certainly see some women finding something interesting or appealing in it. But…you do have to read against it, I think. It’s just really clearly and viscerally misogynist — almost schematically so in many places.

I think women, like men, have various fantasies…which can include the virginal protected Bella, the married passionate superpowered Bella, the angst ridden but powerful Katniss, the powerful but not so angst ridden Wonder Woman, and so forth. I think that Tomie probably tells you a good bit more about male fantasies of women than female ones, though.

Pingback: MangaBlog — Blogging about the blogger

I dunno. Ito’s comics seem to based solely on the idea of “What gross thing can I do to the human body today?”

While the culture is filtering through into how Tomie and his other characters are depicted, there’s nothing in any of his works that suggest to me he has any intent other than making his readers gag.

It’s not clear to me why you think that working to make readers gag can be walled off from gender or society or narrative. Ito’s manipulating repulsions and desires and fantasies through narrative and art. That’s a pretty complicated endeavor, and I think he puts a lot of thought and genius into it.

“Women’s power for Ito, then, isn’t something that women themselves control. Rather, it explodes from inside of them, distorting their flesh and sending their severed gobbets across the landscape. Female-as-symbol is constantly bursting out of female-as-body, leaving behind a gaping corpse in the shape of a vagina dentata.”

The essay, and the discussion around it, makes assumptions about the artist and his intent that we have no evidence for (Unless you have an interview somewhere about it.) beyond the needs of the essay and politics of the participants discussing it. Perhaps Ito *is* like Sim and he sits down at his art table muttering, “Sluts” over and over to himself as he draws.

But nothing about how he presents his stories strikes me as having any agenda beyond, “How do I get a cyborg shark to chase this guy?” He uses bog standard horror tropes as the coat hangar for his scary art.

There’s a lot to be said about the gender and cultural politics of those tropes that he uses. But I think Ito’s cigar is just a cigar.

He uses tropes that can be interpreted as tropes; he tells a story that can be thought about and responded to. I don’t love the Tomie stories, but I do respect Ito way too much to dismiss him as that empty headed.

You’re making all kinds of assumptions yourself about what intention is, how narrative works, and where and when we can bracket fiction off from ideology, ideas, or thought. If it makes you feel better, you can see my reading as an aesthetic response rather than an interpretation. I really couldn’t care much less what Ito’s intentions are, or whether he’d agree with my reading. I read what he had to say and I responded as I responded. I’m not making some sort of scientific claim about what he does or doesn’t think; I’m exploring ideas he provoked. It’s a conversation, not a diagram. Fair enough?

Or as another way of thinking about it…a lot of what I’m saying here is that his work reflects and mirrors tensions and gender politics in Japanese society. That suggests (or *could* suggest) a lack of thought rather than deliberate intent. If he’s not thinking too hard about what he’s doing, then the “thought” in the work could be seen as coming from outside of him. How do you make a narrative without making a narrative? You let the narrative make you…which suggests the narrative is a symptom.

I think he’s more conscious than that honestly, but if you really want him to be an idiot savant, that works fine with my reading.

Pingback: Woman über Alles. La donna nei manga horror di Junji Ito. | Conversazioni sul Fumetto

My personal reading of the Tomie series is that Tomie herself doesn’t represent women, but rather is a living misogynist caricature of a woman that ruins the lives of real women as well as men. Men want her, and women either want to be her or are forcibly transformed into her. No one sees until it is too late that Tomie isn’t even human, but rather a living cancer that ruins everything she (it?) touches, man and woman alike.

I can see that; I don’t think it’s too far off from what I say here.

I feel like Tomie is the monster that sexist society creates. A living caricature based on men’s fears about women and their very 2 dimensional characterizing of us. Tomie is dangerous to men and women but her very existence, manifests and continues to replicate because of these very harmful ideas. She’s more idea than a person. She is a mirror which reflects the male character’s very grotesque contouring of womanhood and women.