In keeping with some of the consistent preoccupations of this forum, I figured I’d try to convey aspects of cultural discourse around comics and cartooning and their treatment of deeper social issues in my corner of Europe, Scandinavia. I think seeing these issues of art as polemic; racism; and freedom of expression as manifested in a, to many, largely unfamiliar context might be interesting, and it will certainly be helpful to me to hear the perspectives of the Hooded Utilitarian’s international, predominantly American readership.

Brokiga trailerHD 2012-08-14 leefilm from Linda Hamback on Vimeo.

I

A place to start would be this fall’s media controversy in Sweden, about blackface and pickanniny characterization in a popular series of children’s books with the character Lilla Hjärtat (‘Little Sweetheart’), by Stina Wirsén—a controversy that has recently led Wirsén to decide to withdraw the books from the trade and never draw the character again.

Wirsén has been writing and drawing books about Lilla Hjärtat for a couple of years, releasing six books that together have sold over 40,000 copies—a considerable number in Sweden. Meant for young children aged 0–3 or so, the central character is a little black girl, undeniably drawn in the tradition of the American pickaninny, with big lips and bows tied into her nappy braids.

No one seems to have complained in public about the books until September 21, when an animated film version, entitled Liten Skär och alla små brokiga (‘Little Pink and all the small multi-colored ones’, trailer above), opened in Swedish theaters. The added exposure afforded by a film made a number of people, including several prominent cultural critics and cartoonists, take notice.

Amongst the most vocal have been freelance writer and critic Oivvio Polite, who has helpfully provided an English-language summary of the controversy with pertinent excerpts of interviews and op-ed pieces translated for non-Swedes. In short, the media rollout of the film spurred discussion online—on Facebook, Twitter and elsewhere—among other things about the fact that nobody seemed to question or even address the film’s stereotyped imagery.

This controversy quickly migrated to the mainstream media, touching off a wider discussion of how best to handle problematic imagery, not the least that of earlier eras, and about Swedish children’s culture, with critics pointing out the conspicuous, general absence of non-white characters in Swedish children’s books and entertainment.

The film distributor, Folkets bio, initially denied any wrongdoing, insisting on the film’s humanist and multiculturalist message, arguing that Swedish culture has reached a point where it ought to be possible to ‘stylize’ dark-skinned people in the same way other groups are stylized. Although individual theaters declined to show the film, Folkets bio has stood its ground, retracting (somewhat bizarrely) only the poster. As mentioned, the pressure however eventually became too much for Wirsén and her publisher Bonnier, who have now retracted the books featuring Lilla Hjärtat, apparently with a view to pulp their stock, while Wirsén herself declared on 22 November that she will never draw the character again.

Wirsén and her publisher have maintained all along that her intent was in fact the opposite of what her critics were seeing in the work, namely to promote a multicultural and open vision for children. In her October 23 press release, she further somewhat implausibly denies having taken a cue from the pickaninny or golliwog stereotypes, pointing rather to African and Carribean imagery. In a November 22 op-ed piece for the newspaper Dagens nyheter, for which she has worked since 1997, she further writes:

The controversy… has demonstrated that there are many ways of interpreting Lille Hjärtat. Most people have seen her as she was intended: as a positive and strong, independent character—an exemplar. But there are also people who have interpreted her negatively. She has been attributed a set of traits implying that she—and I—suffer from an outlook and understanding to which I cannot relate and with which I most definitely do not want to be associated.

Joanna Rubin Dranger, one of Sweden’s premier cartoonists and professor of storytelling at the art school Konstfack in Stockholm, as well as Polite’s partner, has also joined the debate. She has emphasized in particular that a cultural product can be racist even if the author’s intentions are not, writing:

How can you represent a (whole) human being if you’re unable to reflect over what is a normative or reductive characterization? How can one avoid being homophobic, misogynist, or racist in one’s picture-making if one isn’t familiar with the visual discontents of how individual groups have been characterized historically?

She and Polite have engaged themselves in the case to such an extent that they have involved their children, who appear on a special webpage “We Are Not Your Motley Crew” holding up protest signs, along with other people. Seeing them and corresponding with Polite spurred an American professor, John Jennings of the University at Buffalo, to enter the debate. He calls Wirsén’s images “obviously racist” and calls for a total retraction of both books and film. He understands that Wirsén’s intentions were different, but notes that one cannot simply use stereotypes like that, “We think we can repossess them, but it is hard to change their meaning. Stereotypes don’t change.”

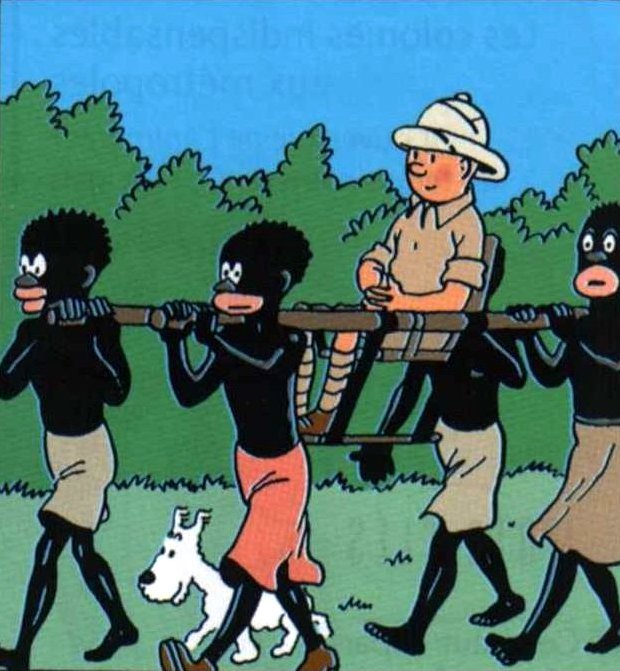

From Tintin in the Congo (1946 edition)

II

While the controversy was raging in September, a related one concerning Hergé’s infamous Tintin in the Congo flared up at the library of Kulturhuset in Stockholm (which incidentally also houses the great comics library Serieteket). Librarian in the children’s/youth section, Behrang Miri, announced in late September his intention to move Hergé’s book and other potentially offensive material to the adult section of the library. This triggered strong protests, not least in the media, with different critics arguing that it would be impossible to determine where one would draw the line, in that most material from earlier times—going back to the Bible and the Koran—contain passages that some find offensive. And further that reclassifying the books would have the opposite effect of what was intended, being a form of censorship that would contribute to a whitewashing of European cultural history. The criticism made Mihri reconsider his decision and the books stayed where they are.

From an international perspective, this debate might be interesting for a number of reasons. For one, it demonstrates how differently racist stereotypes of black Africans are perceived in the historically very culturally and ethnically homogenous Scandinavian countries, where until fairly recently people of sub-Saharan African descent were a rarity. Needless to say, Lilla Hjärtat would be unthinkable in the contemporary United States, and indeed in most of the larger Western European countries. Jennings’ reaction clearly demonstrates this: unfamiliar with the cultural context in which these images have been produced, he applies an American eye, unsurprisingly finding them beyond the pale. A misunderstanding? Perhaps, but also one of the conditions of the globalization of media.

III

Clearly, people at large in the Scandinavian countries tend to be much less sensitive to such imagery than in large parts of the rest of the Western world. Another recent example of such reconfiguration in Sweden was a rather grotesque art installation displayed at Moderna Museet in Stockholm on World Art Day on April 15 of this year. It featured a giant cake made to look like a mostly nude stereotypically “native” African woman, offered to the attendees. The Swedish minister of culture Lena Adelsohn Liljeroth, a special guest at the event, cut the cake from its vaginal region, offering slices to people, while the artist Makode Aj Linde, hidden under the table with his head inside the mask attached to the cake as its “head,” screamed in mock agony. Liljeroth even fed a piece to Linde through the mask. Other people then started serving themselves. (See video above — Liljeroth doesn’t appear in it, but she’s in the photo below. And here’s a rundown of the events for easy reference).

The event caused outrage: first a fake bomb threat was phoned in to the museum, although it is unclear whether it was a reaction to the cake; then a media storm kicked off, headed by the National Association of Afro-Swedes (NAFA) and the Swedish Center against Racism, both of which protested it as a disturbing and tasteless racist spectacle, calling for the minister to resign.

It is hard to see such a manifestation taking place in the United States or the UK, or at least to imagine a prominent government representative or minister officiating in the rather oblivious way Liljeroth did. After the event, she explained that she was there to speak for the right of artists to provoke, but also that she had been asked to cut the cake before having seen it and never intended to offend anybody. This is a strikingly wishy-washy reaction revealing a rather tone deaf grasp of the situation from a minister of culture. More generally, it bespeaks the general obliviousness in the Scandinavian countries to the issues involved. As Mariam Osman Sherifay of the Swedish Center against Racism put it:

In Sweden, it seems to be comme il faut to caricature Africans in ways we could never imagine portraying other ethnic groups which have been persecuted: for example Jews, Romani or Saami people. Still in the 21st century we haven’t dealt with the stereotypical notions of Africans that seem to have been passed on by heredity in Swedish mentality.

The artist, a Swede of African descent, has long been exploring blackface imagery and racial stereotypes in his work and felt that these critics misunderstood his intent, which was to highlight the problem of female genital mutilation. One senses that he also wished to expose precisely the kind of cultural obliviousness around African stereotypes that Sherifay mentions, or—as he stated—to expose “different forms of oppression” simultaneously. He certainly succeeded, if by somewhat dishonest guile: it seems probable that Liljeroth and the other guests were taken somewhat aback and that their laughter in part was an uncomfortable one. But the images of the lily-white Swedish cultural establishment merrily cutting into a mock African tribeswoman remain kind of indelible, and indeed quickly went global.

Swedish minister of culture Lena Adelsohn Liljeroth feeds artist Makode Aj Linde

IV

These controversies demonstrate that the status quo is changing: minority groups have risen in number in recent decades, not least in Sweden, which has the biggest minority populations in Scandinavia. This naturally makes indiscriminate use of stereotypes a much more sensitive issue than it used to be. But just as importantly they raise issues of free speech and civic responsibility in a multicultural society. What Sherifay says is clearly true to a certain extent, but things are more complicated than that. Sweden is not simply the haven of ignorance and chauvinism, where “racism is just a joke”, as she and other critics such Jallow Momodou of NAFA would have it.

It is, rather, a country that prides itself on the communitarian ideals embodied in its social democratic state and in its socially liberal attitudes—attitudes that sometimes result in rather coarse insensitivity. It is worth noting that the initial rebuttals provided by Wirsén and Folkets bio, however wrongheaded, demonstrate their belief that stereotypes can be repossessed and harnessed to address cultural discourse in more nuanced ways and ultimately to fight prejudice. This is quite typical of a culture in which such stereotypes were never particularly concrete in the first place, and while the results might range from the naïvely boorish to the outright offensive, there is also an argument to be made that such cultural misappropriation might indeed occasionally offer new, useful perspectives.

A case in point would be the infamous cartoons of the prophet Muhammad, published in 2005 in the neighboring country (and my home), Denmark. A prime example of local discourse going global and mutating beyond recognition on a much larger scale than the recent Swedish controversies, it started as a mean-spirited (but also ambiguous) stunt by a conservative newspaper, Jyllands-Posten, which was actually met with a lot of criticism locally before the flames were fanned by a small group of unprincipled Danish imams in particular and it hit a nerve internationally, taking on much more ominous and complex dimensions.

Whatever one might think of their ideological content or aesthetic value, the cartoons— not the least the most infamous one, the so-called “Bomb in the Turban”—exposed crucial cultural fault lines in our globalized world. For better or worse one might say, but it is hard to deny the way they have illuminated a certain set of issues that we ignore at our peril. As much as they have become emblematic (however hyperbolically) of Western hegemony and orientalism to many, they have become a symbol (however coarse) of freedom of speech to just as many. A sad, but potent exponent of international tendencies of polarization the temperance of which remains frustratingly elusive, because infinitely more complex than the simplistic us vs. them discourse they have primarily engendered.

V

Although clearly made in a different, smaller, and much less explosive context, something similar could perhaps be said for Makode Aj Linde’s installation, and possibly even Lilla Hjärtat. Certainly some black commentators, including Linde who has supported Wirsén, have stressed that the critics of these cultural products are not speaking for them, and in fact seem to have misunderstood their point. However one wants to take that, the controversies around these works are clearly nestled in a local cultural discourse split between mindfulness of cultural difference and insistence on what is perceived as fundamental civil liberties.

As insensitive as the Swedes might seem in these particular cases, the country is—along with the other Scandinavian countries in different measure—also characterized by a very strong consensus culture, dominated to a large extent by what one might call political correctness. Critics argue that this consensus culture has reached a level of pervasiveness where it is actually harmful, leading to censorship of unwanted ideas and victimization of the minorities who need to be “protected” against them. Additionally, there is an increasing wariness against feeding the ‘culture of victimhood’ that has emerged with globalization—and which was catalyzed by the so-called ‘cartoon crisis’—where individual communities seek to raise their profile on the basis of perceived offenses against them against which they demand action to be taken.

There is a risk that the resultant controversies end up at best being distractions from the very real problems with racism, bigotry or cultural hegemony present in our societies, and at worst actually feeding these by polarizing our societies unnecessarily. The cartoon crisis is a depressing case in point: while it was an eye-opener in many ways, it has ultimately consolidated opposing camps, with the middle ground steadily eroding.

The Swedish actor Stellan Skarsgård, who narrates Liten Skär, surely does not express a fringe sentiment when he says of its critics that they ought to concentrate on real racists instead of attacking this film. The implication being that confusing something comparably innocuous like Lilla Hjärtat, anti-racist in intent if not form, or Linde’s provocative and ambiguous work, with full-blown racism, as Momodou for example does in his piece quoted above, is detrimental to efforts to combat the latter. Sweden has long had a serious problem with racially motivated violence perpetrated by extreme right-wing groups, and there is an argument to be made that the politically correct consensus culture has contributed to this.

By comparison, the political establishment in Denmark, driven by the success of the populist Danish People’s Party, started successfully integrating strong anti-immigration rhetoric into the political mainstream as early as the nineties, whereas in Sweden their equally disagreeable pendant, The Sweden Democrats, were only elected to parliament in 2010. The rise of the Danish right may have led to some of the most draconian immigration laws in Europe, but it has arguably also helped defuse extreme right-wing racial violence, which has never been a comparable problem there.

Of course, Denmark has reaped its own whirlwind after the cartoon crisis, which at least in part needs to be understood in relation to the country’s immigration and integration policies (although Sweden has had its own very similar problems since artist Lars Wilks drew the prophet Muhammad’s face on a dog in 2007). The presence of both international and domestic Islamic terrorists on Danish soil is a new, uncomfortable reality in a country that perceives itself as peaceful, open-minded, and safe. The co-plotter of the 2008 Mumbai attack, David Headley, who scouted the Jyllands-Posten newspaper headquarters in 2006 with an attack in mind; Muhamed Geele, who on New Year’s day 2010 invaded the house of cartoonist Kurt Westergaard, unsuccessfully attempting to chop him up with an axe; and the foiled 2010 Swedish/Tunisian plotters against Jyllands-Posten. These are only the most conspicuous of a longer list of unwelcome guests, whose motivations to seek Danish targets is directly tied to the cartoons.

And events in Norway in the summer of 2011 have taught us all about the threat of right-wing extremism. It is unreasonable to attribute the atrocious mass murder perpetrated by Anders Behring Breivik directly to any specific outside factor, but the facts remain that his delusions of a Norway under threat from multiculturalism tied into the issues at stake here and drew upon extreme right-wing anti-immigration discourse, making it all the more important that we pay attention to how such discourse is shaped. And if we cannot do it in art, then where?

VI

A fundamental question is how harmful the kind of art we are dealing with here is—a question closely tied to the context of their production and presentation to the public. One issue, as mentioned, is that context is open-ended: you cannot make socially, politically, or culturally engaged art without engaging specific contexts, and doing so today exposes you to the risk of immediate appropriation in very different contexts around the world, with the original intent being lost in translation. Even locally, context makes all the difference: for Jennings, for example, Linde’s installation is fully acceptable, because it was made in a high-art context, whereas Lilla Hjärtat and Tintin in the Congo are meant for children and are therefore not. We also generally allow greater leeway for satire than other forms of humor, even though both satire and humor are more often than not dependent on a certain measure of stereotyping to work.

Most civilized countries have laws against hate speech, but the problem is how one defines this term, and to what extent one is willing to curtail freedom of expression in order to silence perceived perpetrators. Surely everybody has their limits on what is acceptable, but if the controversies these last years have shown us anything, it is that one man’s hate is another man’s free. Personally, I have found much of the provocative art—or “art”— engaging these issues in the last half decade tasteless and unnecessary, at times times even abominable, but I hesitate to advocate for legal suppression. It is vital that we keep our societies open and tolerant, especially when faced with the kind of challenges to individual liberty we are seeing today. No matter what somebody believes, says, writes, or draws, it is unacceptable that they should fear for their life or their freedom of movement.

Freedom of expression is not only a right, but also a civic responsibility. If something offends you, speaking up against it, like NAFA and others have done in the cases mentioned here, is a vital function of a free society. As is noting that such criticism is misguided or perpetuates an unhealthy culture of vitctimhood. It pains me to see an artist so shocked by the reactions to her well-intentioned work that she decides to retract it, just as it does once again to have confirmed just how insensitive we can be to certain minorities in our little Scandinavian monocultures, but as long as we stay within the bounds of civilized discourse, it is ultimately healthy for us all.

Appendix: For those interested in getting more of an impression of the debate as it was unfolding in Denmark at the time, here are two pieces I wrote about the Muhammad cartoons, one when as the crisis proper was still brewing and one when it was at its peak.

I’m based in Sweden at the moment and I’ve had a whiff of those controversies even though I don’t follow local news very closely. There are however many parallels in my native Iceland, even concerning the very same Tintin book. Iceland has a smaller immigrant population than Sweden and vanishingly few of African descent so the same naive caricatures of golliwogs and pickaninnies have mostly been called out by a handful of natives, if at all.

Along with Tintin a 90 year old children’s book with a translation of the nursery rhyme “Ten Little Injuns” was republished recently, complete with the original illustrations by a celebrated artist of stereotypical black boys meeting their untimely ends. Some people questioned whether this was appropriate for children or if the book should be republished at all. Other rose in opposition claiming the illustrations were charming and that this was political correctness gone mad. A few months ago at the library I saw a young mother reading the book to her small child in the children’s section.

Supposedly American tourists have remarked on the preponderance of such caricatures here. Other children’s books illustrated in the same style that are perhaps not racist in intent and carry more positive message have not caused a furor, but as far as I know none of them are as recently published as Lilla Hjärtat.

Like Sweden Iceland has until very recently been a very homogenous society and similarly prides itself of its liberalism, although with a different emphasis. A growing immigrant population and suddenly being exposed to more scrutiny has challenged the previously rather easily held notion of racism being non-existent here.

As usual, it’s white Lefties who’re claiming offense on behalf of others.Meanwhile, from the 35 Africans that live in Sweden, silence, boredom, indifference. It comes off as sport on both sides of the debate. The forced multiculturalism itself comes off as a very expensive affectation.

Ormur, thanks for your perspective. I chose to write ‘Scandinavian’ instead of Nordic in the piece, not because I don’t see the same tendencies all over the region, but simply because I’m too ignorant of conditions and events in the countries I don’t talk about. So thanks!

Uland, several of the most vocal critics of these works in Sweden have been of African descent.

Matthias, I know you express some regret…but to me the Lilla Hjärtat outcome seems like a relatively good one. She used racist caricatures unintentionally, without a full awareness of the context. People asked her to stop…and she stopped. Isn’t there an analogy with Herge, who also responded to criticism by working to become less racist later in his career?

That Makode Aj Linde video is something else. Poking around the web, I found this negative commentary.

The writer (Nsenga K. Burton) there doesn’t really seem to be considering the possibility that the piece is an intentional effort to make the patrons look like insensitive fools (at which it was pretty successful.) Comparing it to rap music misogyny (which is what Burton does by implication) seems fairly confused. She says he’s using the piece to “lambaste” the experiences of women…but he’s not denigrating women’s experiences, is he? He’s sympathizing, or trying to show how they’re mistreated, and how racism is involved in the erasure of that mistreatment.

It just seems like (to quote Caro, I think) a representation of racism, rather than a racist representation — a lot more like Mark Twain or Conrad than Tintin in the Congo. Of course, Twain and Conrad get called out for this sort of thing too, and I guess I can see where Burton is coming from as well — the line between showing racism and participating in it can be thin, as some of Crumb’s work shows. But there seems like a lot more thought in this than in Crumb….

As Matthias says, the multiculturalism is forced…but by the fact of globalization, I think, rather than by individual unreasonableness or some such. Demographics in that part of the world are changing, and the current media landscape means that people are visible to each other in a way they didn’t used to be. You can certainly deplore that if you’d like, but it’s not exactly the fault of particular elites, per se.

That Makode Aj Linde video is incredibly uncomfortable, and reading about the controversy surrounding it is interesting. I definitely see it as a Borat-style indictment of the racist and powerful. As such, if raising awareness of FGM was his excuse to get them to go along with it, I think it’s a pretty successful piece. If his earnest goal was to raise awareness of FGM, though, I think it’s terribly thought out.

Surely he did actually raise awareness of it though? He got a ton of publicity….

I mean, that’s true. I can’t argue with that, but the piece itself seems to me entirely geared toward humiliating the racist attendees. Awareness of FGM came totally secondary to the shock at their participation in an (obviously) racist skit. If he was trying to raise awareness of FGM (and that was his primary goal), I would think something more subtle would be in order. Felix Gonsalez-Torres’ “Loverboys” comes to mind as an example of a powerful, damning, heartbreaking piece.

It just doesn’t seem very well thought out as an FGM metaphor. He’s a really racist depiction of an African woman. He’s being cut, and eaten? By white Swedes? Other than the hyper-obvious knife-cut metaphor, I don’t really get the sense that anyone is being made to think about the horrible realities of FGM beyond “it exists”.

(To clarify – (Untitled) Lover Boys (http://ahitinsweden.tumblr.com/post/4559607741/felix-gonzalez-torres-untitled-lover) is a piece about AIDS. I thought it’s a good example of an audience-participation piece that’s really powerful.)

The problem Noah is that, as David Pilgrim put it: “When satire does not work, it promotes the thing satirized.” The high art context doesn’t prevent Linde’s piece from “not working.”

I don’t really see how he’s promoting FGM, though…

I do take Jacob’s point that it seems more aimed at the clueless racism of Swedes than at FGM per se. And using FGM in that way probably isn’t such a great idea….

That’s another aspect that’s not working (at least for me), but I meant racism, not FGM.

By the way, showing political art in a museum or art gallery context (as it seems de rigueur these days) is like advertising in the Sahara desert. Or… even worst: you’re doing it to the enjoyment of the rich and powerful being criticized. Not to mention: to get rich yourself.

Except that this work actually became really famous, right? And has become a touchstone for questions about Scandinavia’s attitudes towards race. I mean, the guy internationally humiliated the Swedish cultural establishment specifically for their racial attitudes. You can argue that he humiliated himself as well, and more or less for the same thing, but I don’t think you can really argue that he ended up speaking to no one.

I’d also question the idea that political art is always embraced or easily accommodated in a gallery or museum setting. The reception/reaction to David Wojnarowicz’s film recently suggests that such work can in fact be seen as threatening, and can be proscribed as well. Art has a pretty solid modern history of actually opposing avant grade individual genius to any kind of collective or communal political action. I think it’s maybe too easy to say that that has transformed so completely that any political art is now just part of the zeitgeist and ignorable because it’s too trendy rather than (as in the recent past) because it wasn’t trendy enough.

Using art for political ends, in any context, always leaves you open to charges of being self-serving, or irrelevant, or (not completely coherently) both. Not that those charges are ridiculous or anything…but all in all, I’d rather have artists try to speak to people rather than just lapse into, or acquiesce to, the alternate solipsism.

I mean…Joseph Conrad seems pretty worth talking about here. Was he just packaging the atrocity of the Congo for the enjoyment of the rich and powerful? How is what he did different than what Linde is doing? (That’s a real question; I’m interested in hearing if someone sees a distinction, and what it is if so).

The art world absorbs any political impact by valuing the work: the monetary value of any piece is inversely proportional to its political impact. That’s Capitalism’s strategy and it has worked very well so far. Capitalism needs to deal with its own free speech and democratic myths. Another strategy is public irrelevance: in an infotainment mediasphere any valuable political message is completely ignored. It also counts on the relentless pace with which news appear and disappear. Not to mention how most people are immune to scandal: everything goes. That said I don’t disagree with what you say above, Noah. I prefer political art (even in an high art context) to escapism, obviously.

“Tintin in Congo” is always used to illustrate the library debacle, but actually, but the tween library where Behrang Miri was artistic director never had a copy to begin with.

(The comics library had one, but they catered to an adult demographic.)

Since the rest of the library staff afterwards denied having had anything to do with the decision to take away the books, at all, it makes one wonder about the motives behind the decision. The reason given was some vague excuse of the books containing “colonalist values” or something akin to it, which might well be true, but it’s debatable why the Tintin books got sorted out and nothing else.

“Sweden has long had a serious problem with racially motivated violence perpetrated by extreme right-wing groups, and there is an argument to be made that the politically correct consensus culture has contributed to this” — Why would that be the case? Are you basing this on the idea that Denmark has less extreme right-wing violence + a less “politically correct” climate? Seems pretty thin to me…

Doesn’t performance art get around commodification at least a bit by not really being commodifiable? I mean, you can record the performance — but obviously we’re seeing it for free here….

H, it may be a problematic conclusion to draw, but I do think there’s something to be said for the analysis, which is one I’ve seen repeated in fairly serious contexts over the years. The extreme right in Denmark has had much less of a leg to stand on these last fifteen years, because much of what they stand for was coopted into the mainstream, without the overt racism (most of the time) and without the violence. They are pretty much a laughing stock nobody takes seriously and don’t seem to have much of a following. Not so in Sweden, where discourse — as you know — has been very different and much more reluctant to address the problems of immigration.

I’m not thereby saying that Denmark has handled these things better — I think we could learn a lot from Sweden, but on the other hand the current success of Sverigesdemokraterne indicates that many Swedes basically feel much the same way as many Danes and that they welcome the challenge to the orthodoxy the party represents. Much as I (and I assume you?), might wish things were different.

As for my regrets, Noah, they basically have to do with what Linde raises in his defense of Wirén: that there’s a knee-jerk aspect to the reaction, one that doesn’t pay attention to nuance but just forges ahead and arguably bullies an artist into silence.

Also, as I mention in the piece, it risks locking minorities into an identity of victimhood, as people who need to be protected from insults, who are not “ready for prime time” in an open society where people speak their mind frankly. This has a tendency to kill meaningful dialogue and distract us from very real problems elsewhere.

More generally: if problematic areas become a total no-go, it becomes difficult to address their discontents, whether in art or other contexts. I believe deeply in moderating one’s speech and behaving well toward others, but I also recognize that at times there’s a need for unwelcome ideas to be aired.

I hasten to add that I simultaneously understand the obvious problems in using a pickaninny stereotype the way Wirsén has, and I don’t actually understand *why* she chose to depict Lilla Hjärtat the way she did — what’s the point? And while I may be skeptical of the criticisms she has faced, they are of course totally legitimate, as I wrote. Plus some of the people who’ve criticized Wirsén, like Joanna Dranger, are people I have a lot of respect for and whose arguments I will take on board on that basis.

I’m very torn on these issues, which is why I chose to write about them here.

Noah: “Doesn’t performance art get around commodification at least a bit by not really being commodifiable? I mean, you can record the performance — but obviously we’re seeing it for free here….”

That was the rationale behind Conceptual Art, but what you get instead are the world’s most expensive photographs.

I love this piece though… However, this comment from Keith Miller tells it all: “Haacke’s brand of political conceptualism challenges the notion that Conceptual Art is an onanistic game for the aesthetically challenged. Few works are so immediately challenging, or cause so immediate a reaction. If only it would happen more often. Now, over thirty years later, one can only hope that more art has the same artless aggression, singular clarity and challenging stance. Boy, would that sell well.”

Oh, yeah; that’s great. But I think this is really not unrelated? It’s biting the hand that feeds you (cake metaphor probably intentional).

Yeah, it can be done. The difference, it seems to me, is that Hans Haacke does just that while Linde is offensive of other people in the process (as comments on the www show – by the way I love those “We Are Not Your Motley Crew” photos: thanks for the link, Matthias!). As I said before though: the art world counter attacks putting the piece in art history and monetarily valuing it. As part of the mainstream it loses its bite. Great as it is it’s now just another aseptic object in an aseptic environment.

”The extreme right in Denmark has had much less of a leg to stand on these last fifteen years, because much of what they stand for was coopted into the mainstream, without the overt racism (most of the time) and without the violence.” – Really? That sounds rather alarming. I have to ask what you mean by ”extreme right” here? And what ideas were sucked up into main stream politics? You’re right in that we do have a few nasty extreme right elements in Sweden, people who are actual nazis or bordering on it. I think you’re also right that there is violence commited by, I suppose, the less sophisticated members or sympathizers of these groups. Now, if their ideas became mainstream we would have a fascist state – so I suppose you are referring to a ”milder” extreme right..?

My experience is that the opposite of what you’re saying is true. For a long time Sweden was an exception in that we didn’t have a party like Dansk Folkeparti or Fremskrittspartiet. Then in 1991 there was Ny demokrati, represented in parliament for one electoral period and pretty much shunned by the established parties. Now, according to your analysis, Ny demokrati’s representation in parliament would have mitigated more extreme expressions of right wing sentiment and right wing violence, right? But the impression / feeling / memories I have about the nineties are the opposite. I was a teenager at the time and I remember people listening to nationalist rock (or whatever you call it), wearing skinhead-inspired attire and scribbling rune-symbols on their lockers in high-school. There were nationalists celebrating Karl XII, marching and what have you, there was violence and even killings. All in all, it’s my impression that there was a more tangible presence of a traditional (and violent) extreme right for a few years, and that they were then pushed back, both by the establishment and on street level. And all of it seems to coincide pretty well with the rise and fall of Ny demokrati. (However, it’s also true that some of Ny demokrati’s ideas on immigration policy were sucked up by the established parties.)

Now, with Sverigedemokraterna in parliament we see the more extreme versions of right wing extremism popping back up too, although the marching boots and swastiskas are more or less gone. I think there’s a triangulation thing happening: with SD becoming more normalised (still pariah for most though), parties like Nationaldemokraterna or Svenskarnas parti (scary stuff with a national socialist slant) seem less extreme in comparison. And I do hear people sighing that it’s the nineties all over again.

But perhaps I’m saying the same thing as you in different words; the extreme right of today are more polished, i.e. as you say the racism is less overt and there is less direct violence..?

I don’t think for a second though that allowing parties such as Sverigedemokraterna to grow in any way reduces racism in society at large, on the contrary.

About ”addressing the problems of immigration”, you may be right in the sense that the established parties in Sweden have been hypocritical: they talk about human rights and international solidarity and the blessings of multiculturalism to look good, which may give people the impression that the borders are open – without that being any where near the case in reality. However, this autumn in Sweden ”the problems of immigration” and similar have been extremely present in public debate, something which I think has been largely detrimental to that same debate because it is blocking out issues that are clearly more important, such as the economy, the distribution of wealth, education, unemployment, housing… Now, of course that’s *my* opinion; Sverigedemokraterna probably do rank immigration as the most important issue – but I don’t see why a party supported by a small fraction of the electorate should set the agenda for all of us..? And if they don’t get to do that, they will claim that we are not ”addressing the problem of immigration”, that the media are biased, etc. So basically, we’re blackmailed into discussing their favourite subject while leaving far more important issues to the side.

It’s also very strange to see the sometimes rather ”advanced” debates described in the blog post co-exist in the public debate with the views of people who can’t see why there would be any difference between a pickanninny or gollywog like picture and the blond boy of Kalles kaviar. I think we lack education (how many of those who defended Tintin have an idea of what King Leopold’s Kongo was like?) and we lack people from minorities who can pedagogically explain to us what it is to be exposed to racism and discrimination.

H, I don’t think we’re in fundamental disagreement. All I can say is that the right wing rhetoric of the Danish People’s Party and the way immigration policy came to dominate much of our political discourse through especially the last decade (thankfully, it doesn’t anymore) seems to have defused a lot of anger on the far right here, of which there was more in the nineties. And while I agree that the prevalence of immigration in political and public discourse became disproportionate, it also helped shed light on real issues that needed addressing, and existing policies that simply weren’t working. *Some good came of it, even if I think it has been damaging to our society as well.

As I see it, Sweden hasn’t had remotely the same open debate about the real issues and I very much hope that it will be possible without the right wing hijacking the political center on immigration the way they did in Denmark.

My recollection is fairly vague, but as I remember Ny Demokrati, it was more extreme in its rhetoric than Sverigedemokraterne, and less uncomfortable with its roots on the extreme right? (Correct me if I’m wrong) What you’re saying, that the right wing has started “cleaning up its act”, appearing more presentable is certainly true and — I agree — quite disconcerting, but one thing it does mean at present is that violent extremism is marginalized even further than it was before. At least that’s been the case in Denmark.

Matthias,

well, the core question here seems to be: if there is a populist party with an anti-immigration tendency in parliament, does that limit the amount of even more extreme right wing activity? My feeling is that it doesn’t and yours that it does: perhaps it’s different depending on the country and the political movements involved. To give a general answer to the question we’d need a hell of a lot of research :-). It wouldn’t suprise if quite a few scholars had already tried to look into this issue though.

When you say “real issues” what do you mean?

About Ny demokrati vs SD: my impression is definetely that Ny demokrati was more of a right wing populist party, based on stuff like “common sense”, “law and order”, lower taxes and also a more restrictive immigration policy, something which in some cases may have degenerated into xenophobia or even racism. But it wasn’t a nationalist party and it didn’t have its roots in the traditional extreme right! SD on the other hand are nationalists and “social conservatives” and they do have clear connections to movements such as “Bevara Sverige svenskt” and worse. They are highly uncomfortable with this today though, at least officially. As a neat illustration: up until 2006 the party had a hand holding a blue and yellow torch as their symbol (I think the National Front in the UK and Front National in France have used similar sporting their countries’ respective colours). Since 2006 their symbol is a flower. So yeah, big clean-up, apparent discomfort and probably a large non-racist following, but they *do* have roots in and connections to the extreme right.

Thanks for that corrective to my faulty memory! SD in many ways sounds worse than DF (Danish People’s Party), but then even before DF’s rise in the nineties, we didn’t have nearly as large a nationalist/fringe right wing presence in Denmark, so the problem is probably a lot more complex than merely the issue we’ve been discussing.

When I say real issues, it’s in large part the almost non-existent policies to integrate immigrants and get them work in the nineties that I’m thinking about, but also the rather uncritical system of family reunification, which brought in a large number of immigrants with which the system had no reasonable way of dealing in those years. That’s changed. Though far from perfect (in some ways unpleasantly draconian, actually), the system is still better now at accomodating and training people from abroad with little or no education and in teaching them Danish.

Another major issue back then, and to an extent still, was the reception of asylum seekers, whose case hearings were often so long that they had to live in centers for years without being allowed to work. That problem is not solved, but steps have been taken to improve the situation. Things like that.

Is it a commonly known fact in Denmark that Sweden has more right wing extremism than Denmark? I know we have some of that, so I see no reason to question your statement, but I have never heard it before. Perhaps another example of that Swedish disease; we think everything is better here! ;-)

So by “real issues” you mean basically integration and things relating to the asylum process (?). I agree that these are real immigration issues, and perhaps you’re right in assuming that if we don’t have good policies in place there, that will generate success for populist and/or nationalist right wing forces. However, when the SD say they want “discuss the real issues”, the stuff that is taboo and silenced according to them, it has no credibility in my book. As an example, I just watched their party leader’s Christmas speech. About 90 percent of the time he was talking about Christmas traditions and decorations, saying how our traditions, and in the longer run, our nation are under threat. Now he’s saying this in a *Christmas* speech on national TV surrounded by a Christmas tree, an “adventstjärna” and a heap of Christmas presents. But yeah, Christmas is under threat. Do you see my point? They say they want to debate, but they use their media time for non issues. Another classic is to report on crime committed by immigrants or problems in areas where many immigrants live — but I rarely see them proposing any solutions, so I conclude that they are more interested in painting a scary picture than in actually debating and finding better policies.

That sounds ridiculous, but from the reports that I’ve been reading, SD also talks about things such as the Swedish family reunification system as a problem, which seems very parallel to the debate here in Denmark in the nineties and early naughts, and I wonder whether there might not be a need for looking more closely at how immigration is processed and how immigrants are accommodated in terms of finding jobs, etc. in Sweden?

My hope is that you will achieve such a debate in a way that cuts out a lot of the bullshit that went along with it here in Denmark, but am of course not holding my breath — SD seems really intent on stirring it up.

As for right-wing extremism, I think it’s a pretty well-known fact that it’s much more of a problem in Sweden than in Denmark. There is nothing like the Swedish virulent, fascist fringe in Denmark; the few aspirants we lamentably do have are basically laughing stocks. But then, as I said, we have government policies on immigration that are often inhumane and a general tone of discourse on the issue that is much coarser than in Sweden. Or less politically correct, if one prefers to describe it as such. I, for one, really wish there was a middle ground somewhere.

Well, “family reunification”… we have “anhöriginvandring” ( = immigration by family members / secondary immigration). You have the right to bring your spouse or any unmarried children under 18, if you yourself are a resident in Sweden. It’s also possible to bring someone you intend to marry — in which case the authorities will try to figure out if you’re serious about it ;-). You *may* be granted to bring other relations under special conditions. The laws were changed in 2010; since then there is a requirement that, before you bring your relation to Sweden, you should be able to support yourself + to house the person that is to arrive. (However, this doesn’t apply to those who got asylum as “refugees” = 25% of accepted asylum seekers in 2011).

If there are problems with this system? I honestly don’t know, apart from problems locally, in communes having received refugees that are then suddenly to accomodate many more people on short notice. What was the issue in Denmark?

The SD want to cut asylum and secondary immigration by 90 %, so yes, you might say they would like to modify the system. I don’t know what rules exactly they’re suggesting instead.

“a need for looking more closely at how immigration is processed and how immigrants are accommodated in terms of finding jobs, etc. in Sweden” — yes! You know, on average, as a group, Swedish residents born in other countries have a higher education than those born here and many (possibly 70 %) have jobs that they are over qualified for! So something is definetely amiss on the job market. Unemployment is also much higher among those born abroad. And then we have a new group of immigrants who have little or no education at all — that of course is a challenge. And I think we have very serious problems with segregation, both social and “ethnic” in nature (something which the current government seem to be aggravating if you ask me). You know the story: there are areas where everyone is poor and hardly anyone has a job and immigrants are vastly overrepresented. The minute someone is succesful, they leave. We definetely need to fix that. I also think there are problems locally, in certain communes. So, I agree, there are many things that need to be done in a better way, some relating specifically to immigration and some to society at large (such as socio-economic segregation and unemployment levels). I know too little about the processing of asylum applications to say anything about that, but the system was changed recently (2006), introducing special “migration courts”. Under certain conditions you can also work while applying for asylum — at least one good thing, although I’m not sure who’d employ you :-(.

(Sources: http://www.regeringen.se/sb/d/13974/a/157999

http://sverigesradio.se/sida/artikel.aspx?programid=3993&artikel=5124116)