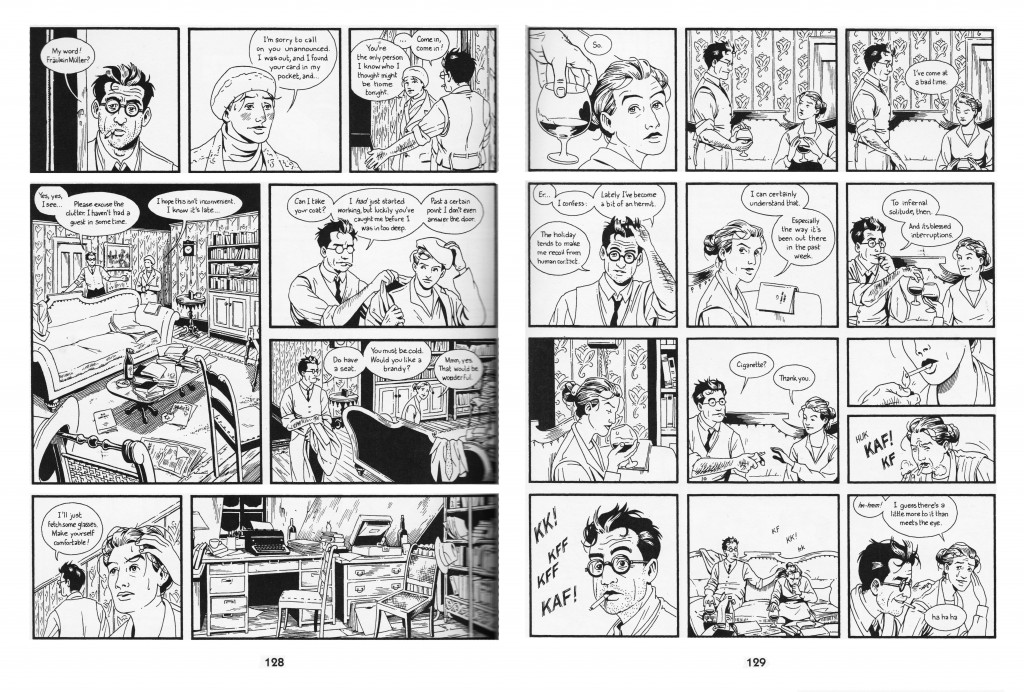

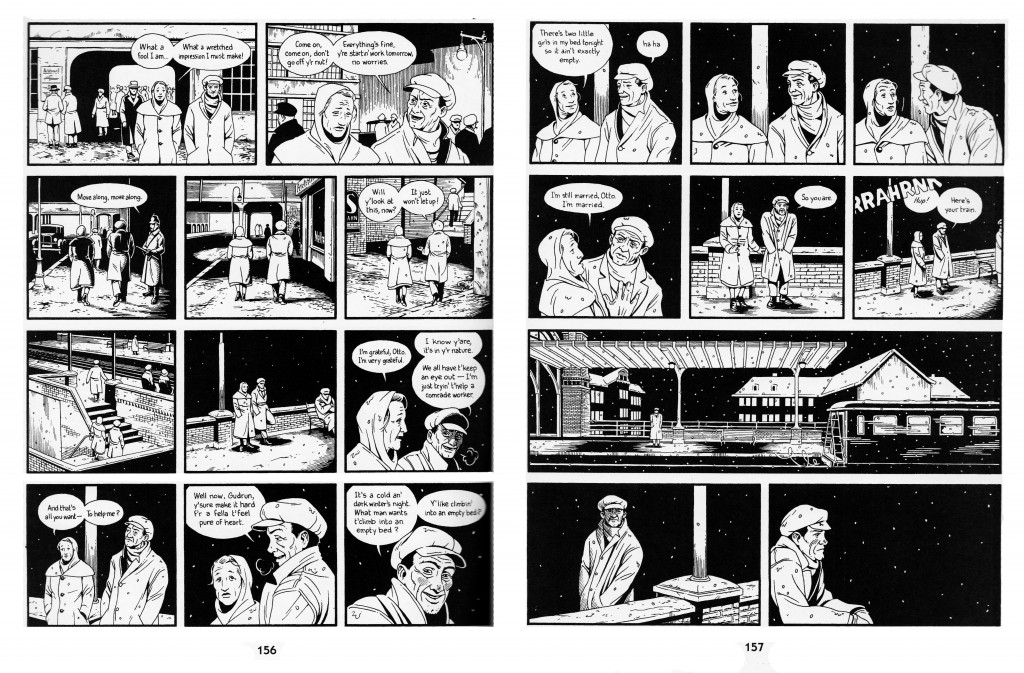

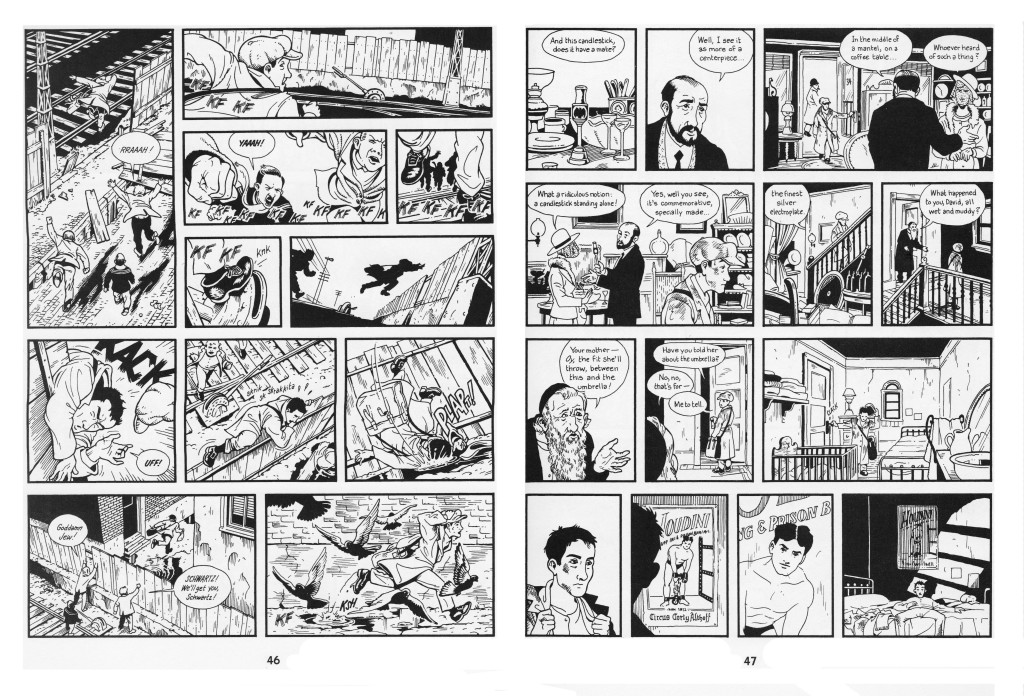

Jason Lutes’ Berlin: City of Stones is illustrated within an inch of its life. Painstakingly researched and precisely drawn, its pictures work overtime to breathe life into history and the fictional persons of its sprawling, yet relatively schematic narrative. The story opens with the arrival of Marthe Muller, an upper class, unmarried woman, who plans to take art classes in Berlin and escape the spectre of an arranged marriage. On the train, she encounters Kurt Severing, a jaded journalist who is struck by her innocence and her self-taught drawing skill, (and presumably how these inform each other.) The book orbits around their transforming relationship, while hopping through the private lives, memories and dreams of disparate citizens scattered throughout the city. Sometimes these characters are revisited, sometimes not. Some lives intertwine in mundane coincidences, others in large fateful clashes, like the violently suppressed Communist march on May Day 1929.

City of Stones attempts a faithful visual portrayal of post WWI Berlin in all its tumult, but misses the mark in spirit. Lutes rewards his characters for their impartiality, ignorance and doubt, and punishes those who embrace the frenzy of ideologies that was its zeitgeist. Marthe drops out of art school, declaring, “there’s a lot for me to learn, but I don’t want to know any of it… I can’t reconcile these things with what I see…. more what I feel. But for me [seeing and feeling] are not so far apart,” and this is treated like a heroic act. Her unfamiliarity with the figures of Trotsky and Stalin, while fascists and communists battle around her, is treated by Kurt as both revelatory and charming. But rather than remain two perspectives among many, Marthe and Kurt’s diaries become the book’s most authoritative voices, giving City of Stones its title and articulating its major themes. The only major character seduced by the communists, a weary and sensitive mother, is shot to death during the march that closes the book, while her husband is progressively vilified as a Nazi. Oftentimes, Lutes’ breathtaking mastery of expression and body language is of more interest than the stock protagonists themselves.

More powerful than the characters is Lutes’ recreation of the city in ink. When people walk, they pass through the city, individual block by individual block. Figures are rarely shown apart from their environment, which is rendered with startling specificity and care. Lutes makes good on his characters’ claims that the city envelops them; he often drafts the foreground and background with equal line-weight, which feels like a deliberate philosophical decision.

On one hand, Lutes’ treatment of Berlin celebrates a crucial freedom the comic medium affords its creators; aside from time and training, everything is as equally ‘expensive’ to draw. Lutes is able to realize visuals that would have required a mammoth budget and manpower in any other medium. City of Stones is also less ‘comic-y’ than many books, as it doesn’t immediately participate in the ‘genre’ of comics or its concerns. (However, the romantic union of a drawer and a writer, and their self-exile from art-school and the rest of Berlin, suggests that City of Stones could secretly be about comics after all.) Lutes doesn’t push the envelope on what comics can do, although he achieves some great effects, often in pursuit of cinematic pacing. It begs the question whether Lutes draws comics in order make something similar to film, while retaining ultimate control. This also leaves him with the responsibility to know and accurately represent the story world he has chosen, which in the case of Berlin, exists outside of Lutes. This ‘auterism’ is far from a bad thing: imagine the variety and ambition of comics produced, if more creators made comics for this reason. Its fair to assume many already do.

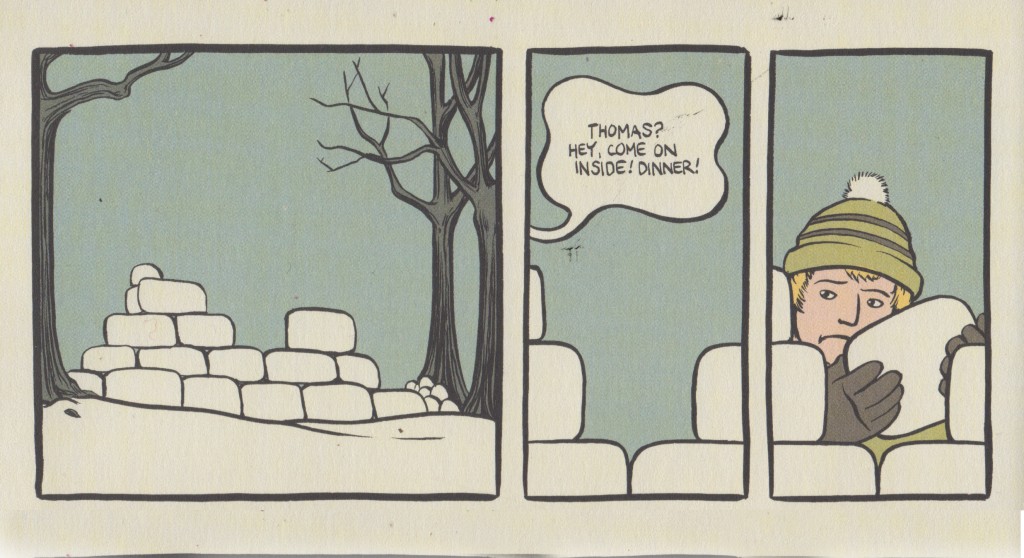

Yet Lutes’ choice neglects, or even rejects, another freedom of comics– the ability to select what is represented. While a camera necessarily records all it can within range, a cartoonist can obliviate a background, stylize its objects, and can render objects into icons or types. Comics resembles memory, where only the essential elements are remembered, or rendered. The act of rendering itself makes what is drawn relevant to the ‘telling.’ For example, in Paul Hornschmeier’s book Mother Come Home, a child builds a snowfort out of flat, immaculate snowbricks.

Hornschemeier doesn’t describe the snowbricks, (crumbling, melting or made in various sizes,) and he barely describes the fort or the activity of building it, in favor of simply depicting the concept of ‘making a snowfort.’ Compared to speed lines, sweat bubbles, and the hundreds of symbols that have been developed in diverse comics traditions, this is a very minor shorthand– Hornschemeier is telling the reader that the child is making a snowfort, without going into detail of what that experience is like. This is left up to the reader, should he or she choose to dwell on it.

Alternatively, this freedom of selection resembles prose writing, where the descriptions add to the fabric, effect and significance of the story, and where a gratuity of description is not appreciated. City of Stones avoids seeming overindulgent because the drawings don’t have to be actively read. They can be visually absorbed (or passed over, unnoticed). At these times, the comic acts more like a film than like a novel. Lutes commits himself to draw like a camera. There’s a tragic nobility here; as a ‘rememberer’ of his narrative, it’s as if Lutes is trying to restore or break through to the world outside of the plot, while working in a medium where this is impossible. By choosing a historical period, Lutes appears to reach for a place independent of his imagination, or the reader’s. Yet the more he reaches and renders, the less room he leaves for his reader to imagine a world outside of Lutes– or late 20s Berlin via Lutes. The act of reading switches over from an active reading to a passive reading, where his audience is not responsible for assembling a sense of the world themselves. This is facilitated by Lute’s tight reign over the pacing.

This core irony is joined by two others. While City of Stones frequently criticizes the cult of “New Objectivity” which beset post-WWI Germany, Lutes works to draw as objectively and as similarly to a camera as possible. Lutes draws with anatomical and perspectival precision, yet he heroicizes a character who refuses to learn to draw this way. Judging only from the first volume, it’s up in the air as to whether Lutes crafted Berlin so as to criticize this visual oppression, to showcase its inescapability, or to capitilize on it.

This review was written without reference to Lute’s interviews or other writing about Lutes, and without reading the following issues or second compilation of Berlin, which the New York Public Library has so far not made readily available. Its possible that the story’s development will make some of these critiques pointless– perhaps Marthe will get a massive comeuppance for her solipsism. More likely she will lose her innocence. The most tantalizing thread is whether Kurt’s noble political non-commitment will spill over into an ambivalence about Marthe, something City of Stones confronts with subtlety and bite. If only more of the narrative threads carried this sense of mystery. The reader watches so many characters think and do so many private things, in such specific streets and houses, yet the book never achieves real, raw intimacy. Perhaps Lutes tries to show too much for a book that is ironic at its core. Which would be a sad conclusion, because his quest to truly, earnestly represent Berlin is the book’s most remarkable quality.

Some fine perceptions here, but much that is head-scratchingly “off.”

Unfortunately, it’s the fly that detracts from the lovely ointment it’s mired in, and its equivalent inspires responses…

—————–

Kailyn Kent says:

Comics resembles memory, where only the essential elements are remembered, or rendered.

—————–

Sorry, but in memory all manner of unessential details are also recalled. And wouldn’t an “only the essential elements are rendered” comic look like this? http://2.bp.blogspot.com/_A6_jp6ECaw4/TT2gO0AdW1I/AAAAAAAAAKg/YZd_TvcJzVM/s1600/man-and-woman-bathroom-signs.jpg .

These sweeping statements sound so fine, have such an authoritative assurance; and then reality butts in.

——————

The act of rendering itself makes what is drawn relevant to the ‘telling.’ For example, in Paul Hornschmeier’s book Mother Come Home, a child builds a snowfort out of flat, immaculate snowbricks.

Hornschemeier doesn’t describe the snowbricks, (crumbling, melting or made in various sizes,) and he barely describes the fort or the activity of building it, in favor of simply depicting the concept of ‘making a snowfort…

——————-

Indeed comics can do such a thing. And painting too: in “The Silver Warrior,” Frazetta “depicts the concept” of polar bears pulling a sled, not bothering to render harnesses, reins: http://images.tribe.net/tribe/upload/photo/3bd/b59/3bdb59b5-90aa-4c3f-9912-39009ac39f87 . In comics, John Byrne “takes it to the max.” See, or don’t see, for yourself: http://www.comicsgrid.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/03/Alpha-Flight-006-Page09.jpg .

But, is it then a flaw if a creator chooses not to deploy the full armory of aesthetic effects an art form possesses?

And what about all the other creators — Lutes is hardly alone in this — who don’t depend on the reader to “fill in the blanks” as far as detail, verisimilitude??

———————

Lutes’ choice neglects, or even rejects, another freedom of comics– the ability to select what is represented. While a camera necessarily records all it can within range, a cartoonist can obliviate a background, stylize its objects, and can render objects into icons or types.

——————–

Uh, even the so-called “photorealist” comics artists (some of whom make Lutes look as cartoony as Hergé) routinely leave out much texture and detail. See the difference between Alex Raymond’s Rip Kirby: http://2.bp.blogspot.com/-qiXk3NfOp1A/UAG1Q7xJptI/AAAAAAAAAfI/Zf182vNu3EI/s1600/rip2.jpg and a photo: http://www.dsphotographic.com/g2/15058-3/Howarth+1940s+Weekend+-+006.jpg

And, when Lutes renders one character instead of another, a certain angle of view, or crops a figure to a “head and shoulders” shot, is he not “select[ing] what is represented”? (Sheesh…)

——————–

Alternatively, this freedom of selection resembles prose writing, where the descriptions add to the fabric, effect and significance of the story, and where a gratuity of description is not appreciated.

——————–

(???) That word sure doesn’t fit:

http://www.thefreedictionary.com/gratuity

http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/gratuity

So, what is it that isn’t appreciated by readers? Is “surfeit,” or “excess,” the word intended? (But, inconveniently, some writers lay the descriptions on thickly, and their readers savor them. Not every author is lapidary as Hemingway.)

——————-

By choosing a historical period, Lutes appears to reach for a place independent of his imagination, or the reader’s.

——————-

Um, unless one is veryveryvery old, wouldn’t it be inescapable that we would have to imagine living there?

And, if what is meant is that the Berlin of that era had an actual existence beyond our imaginings, then wouldn’t it make sense that Lutes would, as he is charged with, not leave “room…for his reader to imagine a world outside of Lutes– or late 20s Berlin via Lutes. The act of reading switches over from an active reading to a passive reading, where his audience is not responsible for assembling a sense of the world themselves”?

It certainly is a valid approach for a filmmaker to convey the idea of “China” with a montage of Pandas, Ming Vases, the Great Wall, the terra-cotta warriors, and let the “audience [be] responsible for assembling a sense of [China] themselves.” (An audience that likely would feel mightily ripped-off!)

But there is also room for documentary, or travelogue approaches, which don’t rely upon the audience to do the “heavy lifting.”

—————–

This core irony is joined by two others. While City of Stones frequently criticizes the cult of “New Objectivity” which beset post-WWI Germany, Lutes works to draw as objectively and as similarly to a camera as possible. Lutes draws with anatomical and perspectival precision, yet he heroicizes a character who refuses to learn to draw this way. Judging only from the first volume, it’s up in the air as to whether Lutes crafted Berlin so as to criticize this visual oppression, to showcase its inescapability, or to capitilize on it.

——————-

What is so “ironic” about a creator, say, using restraint to depict “letting go,” subtlety to depict brutality, lovely lighting to illuminate horrid acts? No less a control-freak than Kubrick made madness, war — hardly precise, controlled activities — the subject of “Dr. Strangelove.” When movie stuntpeople carefully choreograph an uproarious fight in an Old West saloon, they are not necessarily criticizing drunken brawls, showcasing their inescapability, or capitalizing on them.

———————

Perhaps Lutes tries to show too much for a book that is ironic at its core.

———————

“Ironic” by some awfully odd sleight-of hand. Such as, “Spielberg carefully preplanned, staged, filmed and edited what was actually hellish chaos, the landing on Normandy and scenes of WW II. Therefore, ‘Saving Private Ryan’ is ironic at its core.” Or, “Hitchcock carefully preplanned, staged, filmed and edited what actually would have been hellish chaos, a knife-murder in a shower. Therefore, ‘Psycho’ is ironic at its core.”

If I might recycle comments (and my responses) from old HU threads:

—————–

Evan Zuk says:

Nazis in these realist depictions [of Holocaust art] are something the audience reacts to, not something the audience relates with.

——————

Yes. Though — as shown in Jason Lutes’ great “Berlin” — it is possible to make them “relatable”…

…”Berlin” is exquisitely wrought, a complex canvas showing a wide scope of humanity the likes of which we haven’t seen since Alan Moore’s more “genre-y” writing in “V for Vendetta” and “Watchmen.”

…The cast of characters is richly varied and brilliantly created. There is a wonderful lack of “presentism”: the scene of a middle-class couple, in their humble but cozy home, where the husband tells his wife that he’ll vote for the Nazis because after all they went through in the Depression, all they struggled for to achieve this little bit of stability and domesticity they now have, he won’t have the Bolsheviks take that away.

There are splendid incidental characters like the chap who stands in the traffic-control tower, bemoaning the lovingly prepared but constipation-inducing lunches his wife prepares for him. The brutish dolt whose killing by a Bolshie would inspire the “Horst Wessel Song”; countless others…

And — unlike the dry and dusty tome the research-phobic would expect — “Berlin” features some of the most thrilling sequences I’ve ever seen in comics. Two of which remind how amazingly powerful classical restraint can be. (In painting, consider the pinnacle of this discipline, Piero Della Francesca.)

In one, a splendid young Jewish man (what, there’s no Wikipedia entry on the book, to remind of his name?*) tells of his adoration of Houdini, the magician’s extraordinary feats. Has the excitement of a character ever been so palpably communicated?

In another, a Nazi holds up his little girl, that she might better see a speech by “Our leader…the Gauletier of all Berlin.” (Quoting from memory). Who is Joseph Goebbels. Rather than presentism-loaded editorializing — “How could these Germans be such fools as to be taken in by this charlatan? — Goebbels’ speech, simply a series of talking-head-and-shoulders shots — is unspeakably powerful; the clipped, dramatic phrases, Lutes’ use of body-language within those constraints, “editing,” making one feel, there but for the grace of God, if I’d been one of those thronged around, at the end of that speech I’d have joined along with Goebbels as, at its climax, he shouts (the first time in “Berlin” we hear the name, if I remember right), “Heil Hitler!”

Two interviews with Jason Lutes: http://www.comicbookresources.com/?page=article&id=17764 , http://www.bookslut.com/features/2009_01_013875.php .

*Since I wrote that post, one has appeared — http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Berlin_%28comic%29 — though it’s painfully skimpy.

Thank you for this thoughtful & intriguing essay on Lutes’ work, Kailyn. I started reading Berlin in its serialized form in the 1990s, and even then I sensed a kind of distance in the work; maybe this is a consequence of the fact that, as you suggest, the city itself is a character all its own, but I have wondered since I started reading the book if it is some sort of autobiography, but one mediated by the historical framework Lutes has created.

(Is Berlin a distant relative of Tati’s film Playtime, in which the characters are just tiny moving parts in the vast machine of a modern city?)

Do you think Lutes achieves the intimacy in Jar of Fools that seems to escape him in Berlin? Is Jar of Fools simply Berlin’s more intimate, raw, and emotional twin?

I should also mention that Jar of Fools, Berlin, and James Sturm’s The Revival were the books which coaxed me back into reading comics in the mid-90s after I’d fled in the midst of the black & white implosion of the late 80s. I have a great fondness for Lutes’ work. It’s wonderful to see him getting the serious consideration he deserves in your essay.

Thank you guys for reading! Great insights Mike!

Brian– I had a lot of difficulty writing this piece, because I love Lute’s work much more than I let on here… for some reason, this was what came out! And my thoughts have already changed with the second book, which serendipitously arrived at the library the day this was published. Your thoughts mean a lot to me, and I’ll let you know what I think in regards to Jar of Fools.

I met Jason Lutes many moons ago shortly after buying Jar of Fools‘s first Xeric funded edition (1993). I liked him and I wanted to write about Berlin. Which brings me to the real reason why I’m writing this comment: 17 years later Berlin isn’t finished! What does this say about the comics medium? Is it an impossibility with real jobs waiting and comics being just a hobby?

Domingos: I think it says something about historical fiction in the comics medium. In prose, you could say, “He opened the door.” In comics, you sit down to draw the panel, and you think (if you work the way I work, and it seems like Jason Lutes might): what did a doorknob look like a hundred years ago? What did a doorknob in Germany look like a hundred years ago? How old is this house? What kind of trim would there be around the doorway? How wide are the floorboards? Filmmakers have the same problem, of course, but they can often outsource it to a team of experts. Comics artists are their own research departments. I’ve been working for two years on comics set in basically the same time and place as Lutes’, and it is exhausting; without the internet, it would’ve been impossible.

That reminds me of that famous story about a Chinese painter who studied a certain topic during a whole year to learn how to draw it perfectly in five minutes, or something like that… I believe you, but those who apparently have easier jobs don’t have their work facilitated by their day jobs either. Another example is Seth’s Clyde Fans. When will that one end? And why is he doing stupid stories about comics fans and comics collectors instead?

Thank your for this. Really. Having just, coincidentally, read both volumes back to back for the first time, I had many of these ideas floating around in my head this past week. In regards to this:

“(…) Lutes commits himself to draw like a camera.”

I though the same thing until near the end of the first book, just before that page featuring the two characters naked, absorbed in the contemplation of each others’ bodies, surrounded by a surprisingly uncluttered background of both grassy knoll and clear sky, where the apparent “gaze” of Lute’s paneling expands both vertically and horizontally to enclose both figures in a self-consciously design-y sort of way. Up until this moment, if I’m correct in my recollections of this very brisk reading, the comic had pretty much kept itself to a strict panel-to-panel action sense of storytelling, but this moment, clearly a metaphorical way of following up the woman’s declaration of love, opened up a whole dimension of page design that might’ve helped the purely dramatic (i.e. fictitious) part of the story read better as a novel (whereas, up till that point, it had an air of historical fiction clogging up the more subjective of the narrative’s liberties, specifically the brief and anonymous monologues by the various citizens paraded throughout). This is reflected in the final pages of the book, when the communist mother is lying on the ground, thinking back on her own intimate moments shared with her now-estranged husband.

This realization of how Lutes puts in so much work, only to change it up in key moments, resulted in a very enthused reading of the second book, where I’d hoped to find more use for the manicured but still joyful sort of panelling he’d only briefly hinted at during the first. But, alas, he only pulled an all-white background or borderless panel occasionally.

I know it wasn’t any fault of the artist that my hopes went unfulfilled, but I still feel like, with the inevitable calamities to befall the characters in the third part, I’d like to see him plumb the depths of the storytelling capabilities he so ably hinted at in the previous volumes. Breaking away from that figurative and sometimes “cinematic” way of telling the story, though only slightly, I think would greatly improve and help balance out both the story itself (with its competing tensions of historic accuracy and almost poetic dramatization of lives intertwined) and the theoretical framework upon which it structures itself as a written AND illustrated text.

[I apologize if this reads as a somewhat convoluted response to your original post, but I’ve only just (i) finished reading both volumes and (ii) taken the time away from writing something completely unrelated. Which is to say, I’m kind of a mess right now.]

Domingos:

Isn’t “Clyde Fans” supposed to end on the infinitely postponed “Palookaville #21”?

Maybe, but:

1) as you say we don’t know when that will be, and…

2) it was, what?, 14 going on 15 years since the first installment?

Indeed. It’d be interesting to see someone raise the issue when it is finally collected in its entirety (hopefully soon?).

Also, “George Sprott” wasn’t one of his “comics about comics and/or comic book people” and it was quite good. At least, as far as I can remember.

Pingback: » City of Irony: Jason Lute’s Berlin, Book One