[Those looking for background details and a synopsis of The Heart of Thomas can do no better than to read Jason Thompson’s review.]

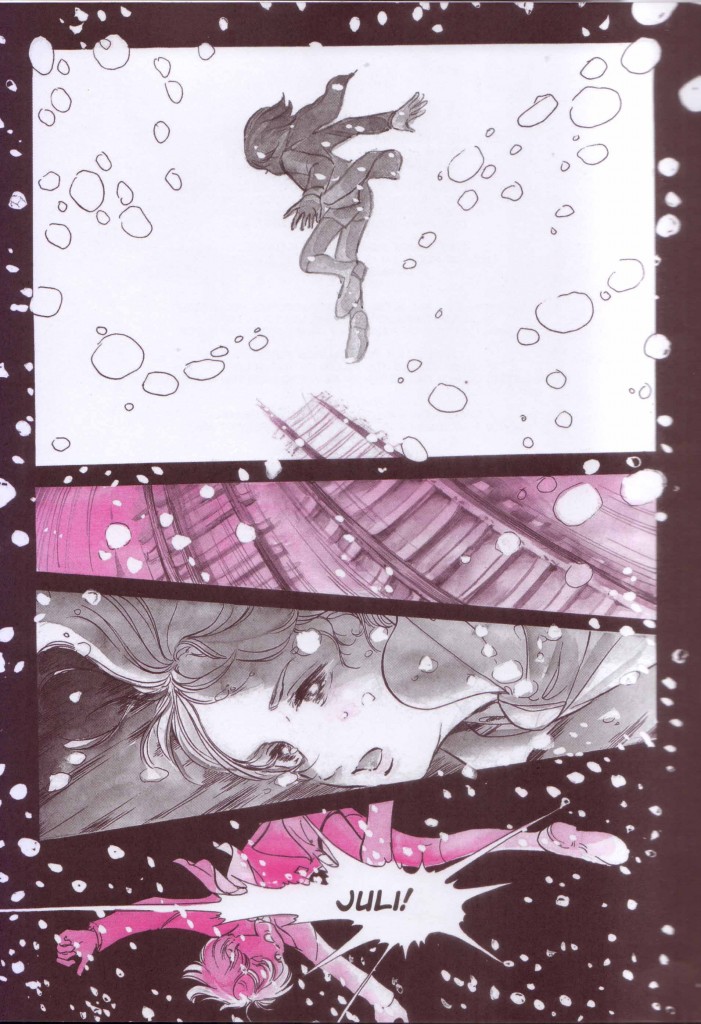

In the opening pages of The Heart of Thomas, the eponymous object of desire and remembrance, Thomas Werner, leaps from a railway bridge to his death.

But who is he? This intangible ghost of doomed naivete crushed by the morass of faithlessness and abandon which has inundated the boarding school which he attends. Perhaps, a metaphor for innocence lost, reborn in the form of his more resilient lookalike, Erich Fruhling—a boy who soon becomes an indelible memory of that life carelessly thrown away; a soul on the path of transmigration in an alien and barbaric Christian world of torment.

Of course, Thomas’ body isn’t subjected to any tragic or tangible mangling despite the suggestion that “his face was crushed.” Death in Hagio’s world is as chaste as the heated embraces and kisses which reach a crescendo towards the closing chapters of the manga. Even Goethe’s Werther (no first name, similar last name) had the presence of mind to die slowly and painfully 12 hours after shooting himself in the head. Mortality is nothing more than a stylized leap into an endless stream of romantic possibilities in Hagio’s manga. Thomas’ suicide is performed out of love for a senior student by the name of Juli, a distant and correct individual who like all suffering, misunderstood heroes, conceals hidden depths of anguish. The appearance of Thomas’ lookalike, Erich, quite early in the tale—strolling past Thomas’ grave as it were—presents Juli and his classmates with a second chance. He is nothing less than an angelic being. Even the school master seems enraptured by this unspoilt youth—like Hadrian lusting after Antinous. One might almost call it a process of deification. And as with his historical counterpart, Erich is subject to both adoration and recriminations. As Hagio asserts at the start of her story:

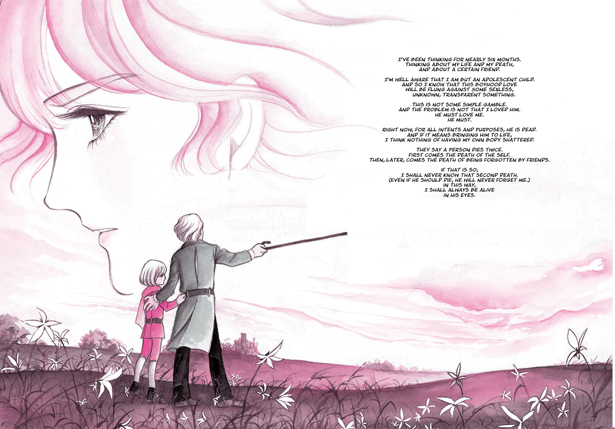

“They say a person dies twice. First comes the death of the self. Then, later, comes the death of being forgotten by friends. If that is so, I shall never know that second death. (Even if he should die, he will never forget me.) In this way, I shall always be alive in his eyes.”

These lines define the authoress’ purpose. The Heart of Thomas rests on a physical manifestation of this remembrance, as florid as a grief stricken emperor’s commerorations of his lover—as if memory had the power to evoke a second incarnation or avatar. Still others might see everything which follows Thomas’suicide as the fantasy of a collapsed mind, the tangled memories and imaginings of a dying brain hoping for a happy corrective to a tragically short life. Certainly, that Germany of the mid-twentieth century imagined by Hagio has no anchor in on our reality. It is an alien planet both to the Japanese and European reader alike—a dream which has no interest in the tradition of Mann, Grass, and Boll but rather adheres to the hysterical breathing, coincidence, and fainting spells of wish fulfillment and hallucination. If these young male students had breasts, they would be ripping their bodices from their angular bodies

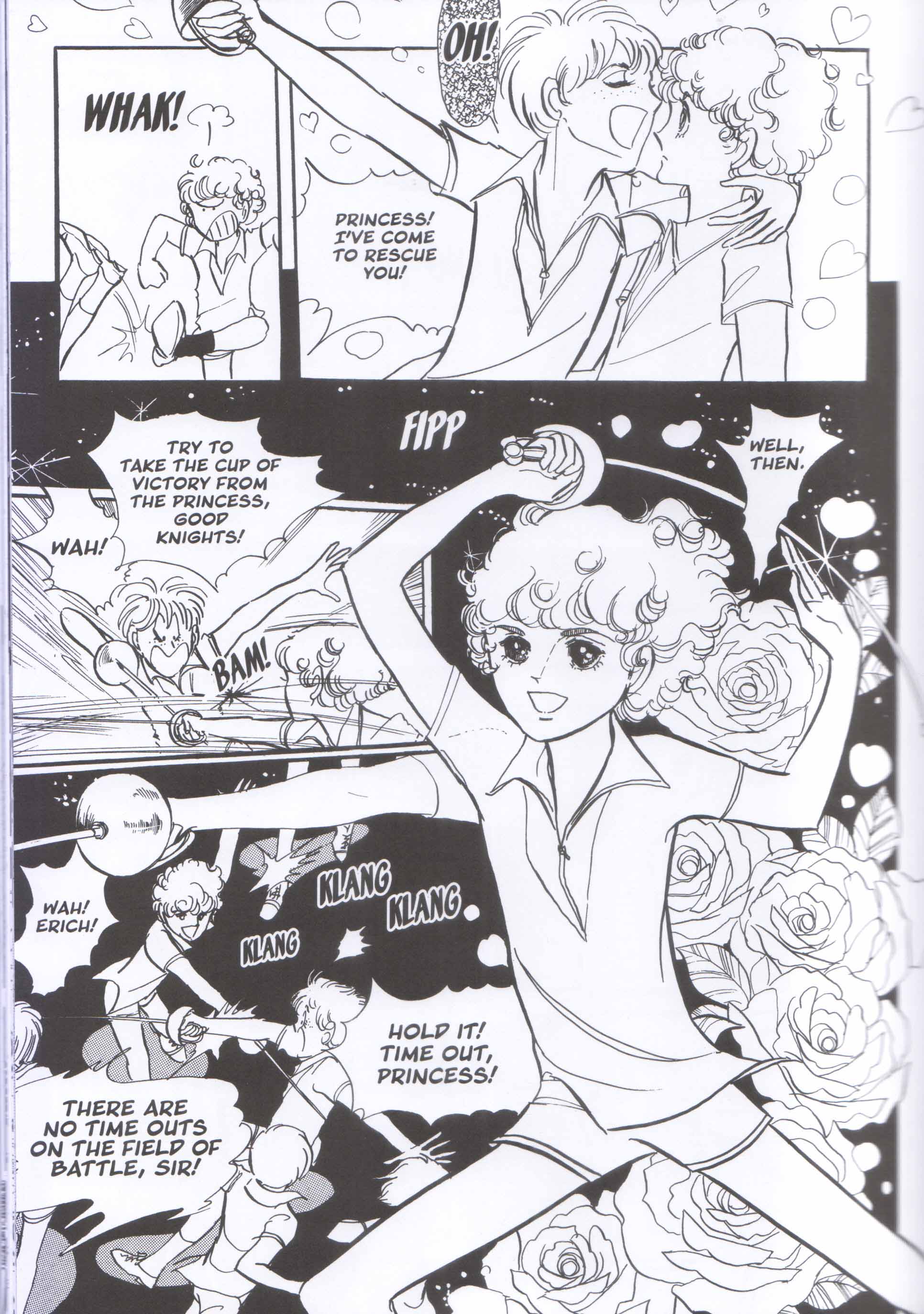

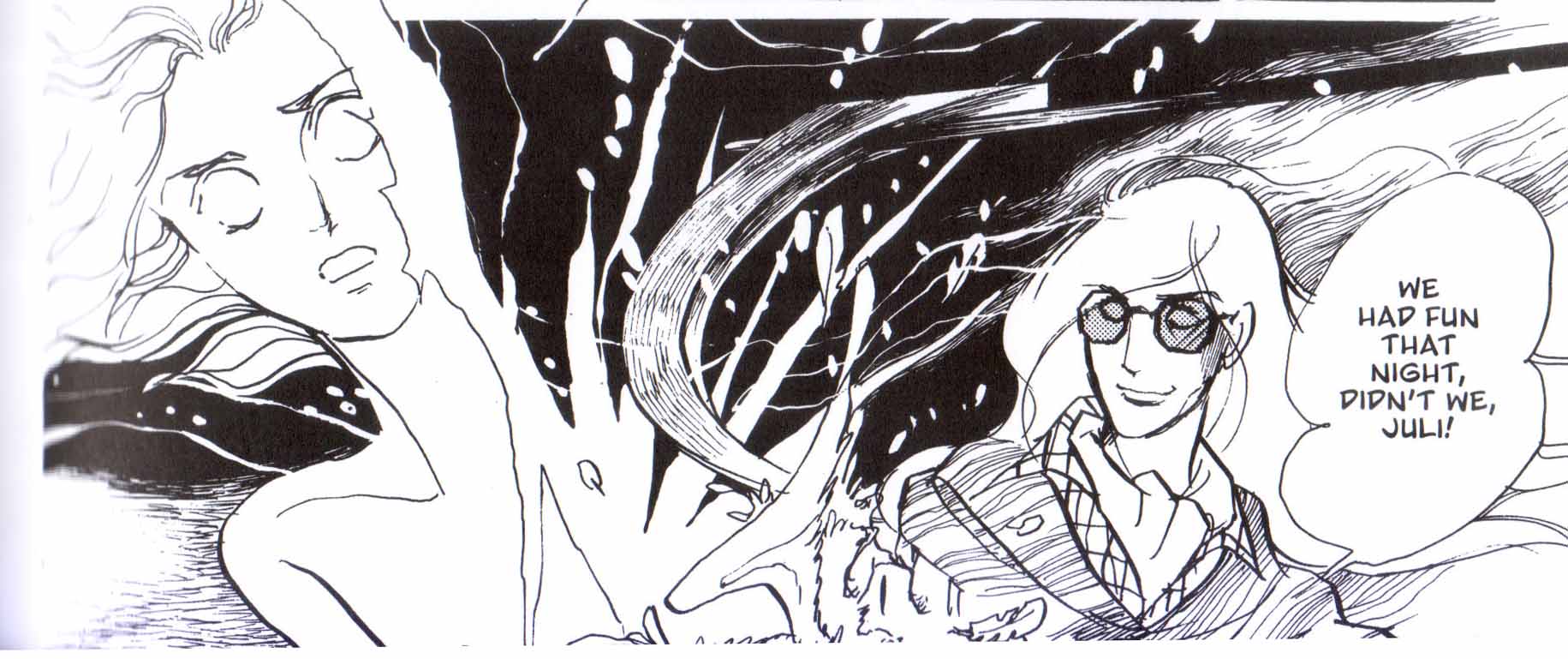

In one early episode, Juli suffers one of his recurrent fainting spells, a neurotic turn resulting from an earlier psychological trauma. It is perhaps the only time you will see an individual getting mouth to mouth resuscitation while he is having a “fit”. The fraudulence of this medical act suggest it’s placement—if it isn’t clear already—for erotic effect. The penis is verboten but a number of alternatives are grasped with both hands. A teacher’s attempt to stroke Erich with his cane is nothing less than a metaphor for the sexual tensions within the school. When the reigning queens of that exclusive institution arrange to converse with and touch Erich at a tawdry but chaste tea session, he barely manages to fend off their ministrations. This high tea of the mildly depraved is a kind of half-baked, elementary school version of the Hellfire Club where “Do what thou wilt” shall be the whole of the law.

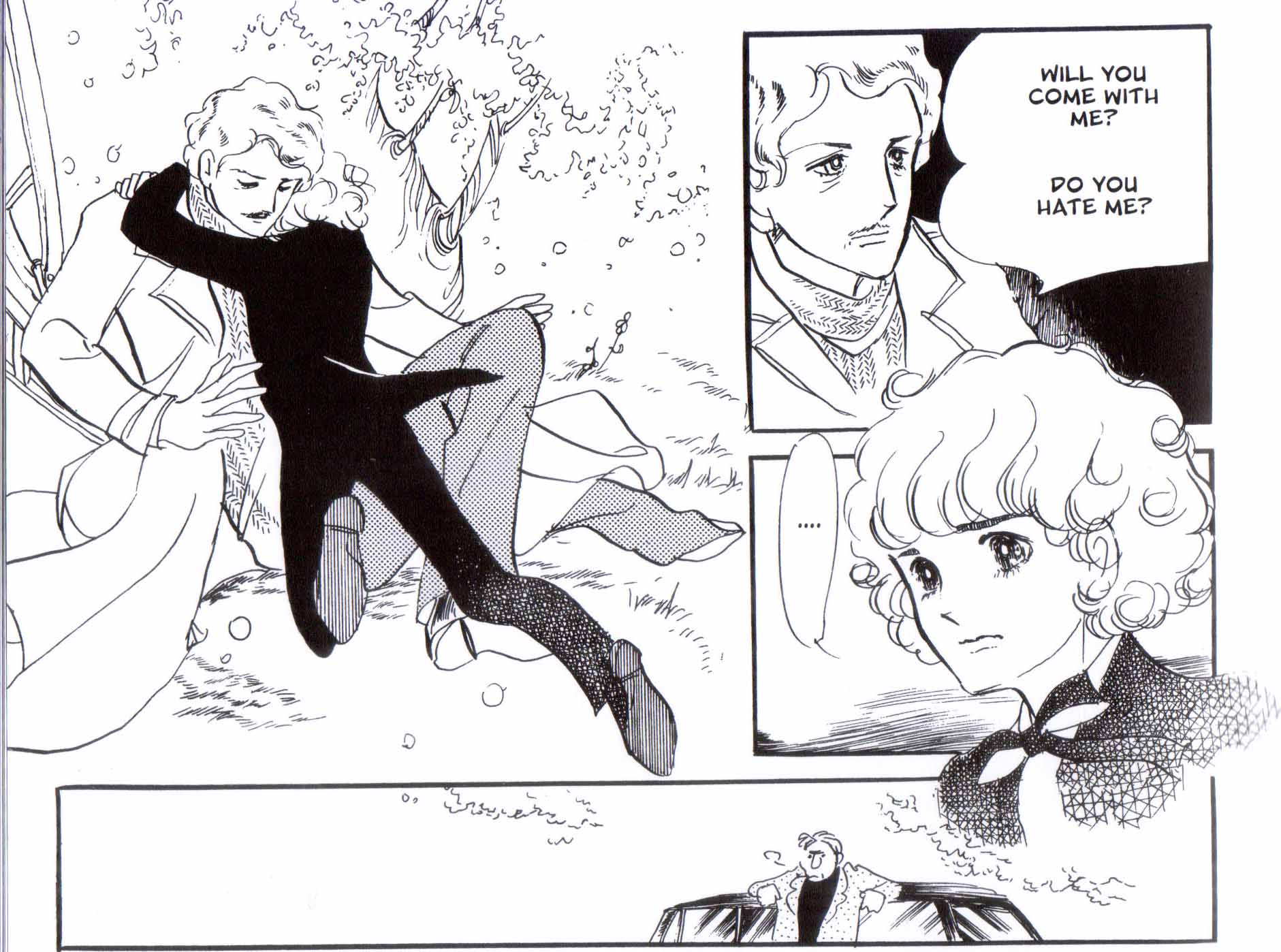

There is the pesudo-coitus—between Juli and Erich—of grasping with sharp objects: first in the fencing room and then, somewhat less subtly, in the bedroom with a pair of scissors. Later, Erich recounts a tale where he indulges in the predominantly male practice of autoerotic asphyxiation. These recurrent acts of strangulation are brought on by the sight of his mother kissing her lover—his mental torment (and patent mommy issues) relieved only by the death of his mother and a profession of fatherly love by his mother’s lover.

This incessant intermingling of pain, death, and love is Hagio’s idée fixe; and the purity of male love the panacea for all depicted ailments. The only exception to this gloss on idealized homosexuality (a fanciful and hopeful template for a paradigmatic relationship between the sexes) is Juli’s physical and likely sexual abuse at the hands of another student named, Siegfried—that swaggering, heroic betrayer of Wagner’s Ring cycle here seen as lascivious, preening monster with an appetite for sadism and young boys.

Erich’s allusion to a meeting between Beethoven and Goethe suggests the essence of the relationship at the center of Hagio’s manga. Here is an excerpt from a Gramophone article concerning Goethe’s feelings after that fateful meeting:

“Shortly afterwards Goethe penned a more qualified verdict to his musical guru Carl Zelter: ‘His [Beethoven’s] talent astounded me; nevertheless, he unfortunately has an utterly untamed personality, not completely wrong in thinking the world detestable, but hardly making it more pleasant for himself or others by his attitude.’”

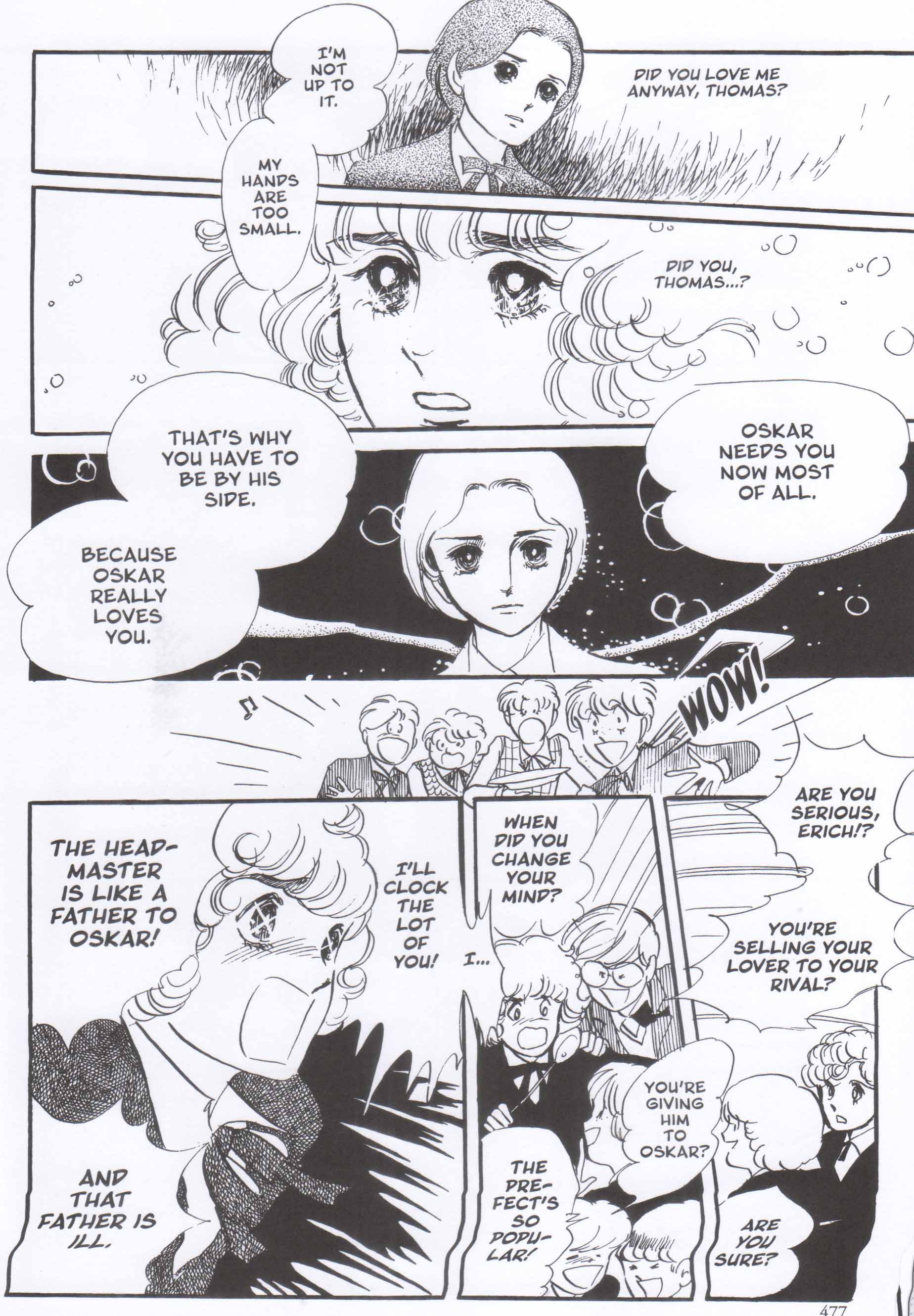

Erich is of course Beethoven in our boarding school equation. Juli’s rejection of his “untamed” sensuality—forged and broken through terror by Siegfried—is the root of all his troubles. When Juli tells Erich, “I am going to kill you,” it is not merely a prediction based upon his earlier role in the death of Thomas Werner but a sign of Juli’s repressed sexuality—a disease which manifests itself in the weird science of mild attacks of “anemia” which have no basis in medicine.

The reader’s mileage with respect to Hagio’s subtle eroticism will vary depending on his/her passion for the artist’s figure work and for characters with brittle foreheads in need of warm towels. Not that these aspects aren’t apparent to Hagio. There is, for example, that moment of epiphany when one of the characters complains that his fellow students feel that he has “a girl’s face;” an otherwise unremarkable statement except for the fact that just about everyone in that boarding school looks like a pre-pubescent (i.e. breast-less) girl. To be sure, readers of The Heart of Thomas should always assume that every woman in Hagio’s work is actually a man until proven otherwise. This isn’t a problem so much as a feature of the genre, the attractiveness of slightly feminine men (or in this case feminized yet adequately virile men) being the entire point. To imagine the alternative—consider going to an action movie in which nobody dies and no violence is performed. It just wouldn’t do.

Noah in his article at The Atlantic offers little in the comics’ defense except for the standard, “Well, it’s meant to be crap and succeeds admirably at it.” Not his actual words of course, but here they are for those so inclined:

“In a lot of ways, The Heart of Thomas is an Orientalist harem fantasy in reverse. Instead of a Westerner thinking about veiled maidens on cushions in some distant palace, the Japanese Hagio fantasizes about beautiful boys in an exotic Europe.

The genre of boys’ love, in other words, allows Hagio and her readers to place themselves in a position of power and aggrandizement that is rare for women—as the distanced, masterful position, letting his (or her) eyes roam across variegated objects of desire….Thus, the prurient fan-service which is usually doled out only to men is here explicitly taken up by women, who get to watch more exotic male bodies than you can shake a spectacle at.”

And on Juli’s emotional (and likely physical) rape:

“Instead, Juli’s rape emphasizes the universality of what is often presented as a particularly female experience. Similarly, Juli’s shame, his self-loathing, and his tortured effort to allow himself to love and be loved, are all character traits or struggles which are often stereotyped as feminine. The fact that Juli is male seems, then, not an aspect of otherness, but rather a way to underline his similarity to Hagio and her audience. If readers can with Siegfried experience distance as mastery, with Juli they experience an empathic collapse of distance so powerful it erases gender altogether…The boys’ love genre, then, freed Hagio and her audience to cross and recross boundaries of identity, sexuality, and gender.”

As Noah periodically ejaculates on this blog, this is a case where the criticism is of far more interest than the text; a situation where purpose is more interesting than result, intention far better than the delivery, and (presumed) effect more fascinating than the actual reading experience. And if, as Noah claims, Hagio is an “aesthete”, this does little to explain the inadequate metaphors, and the banal structure and prose which litters the narrative. The romance here is as invigorating as ice on genitals. Certainly, nothing works so well to preserve mood than a comic chorus commenting on every loving decision and every act of forbearance. At every turn, the manga engenders not so much an “empathic collapse” but a complete nullification of empathy.

The tacked on and thoroughly mangled Christian metaphors (angels without wings; Judas and Christ; a cursory mention of justification) serve only to highlight Hagio’s poor grasp of European culture and religion in general. Even worse is the “shocking” revelation (of abuse) which is anything but. I let out a mental gasp of incredulity when the a plot twist near the close of the comic had Juli threatening to retire to a seminary; a time honored old chestnut seen in both modern and period Asian dramas since time immemorial where women have retired to nunneries for one reason or another. The immense superficiality and unadorned derivativeness of The Heart of Thomas suggests that whatever dividends one might gain from it are largely skin deep. It is nothing less than a time capsule of high camp.

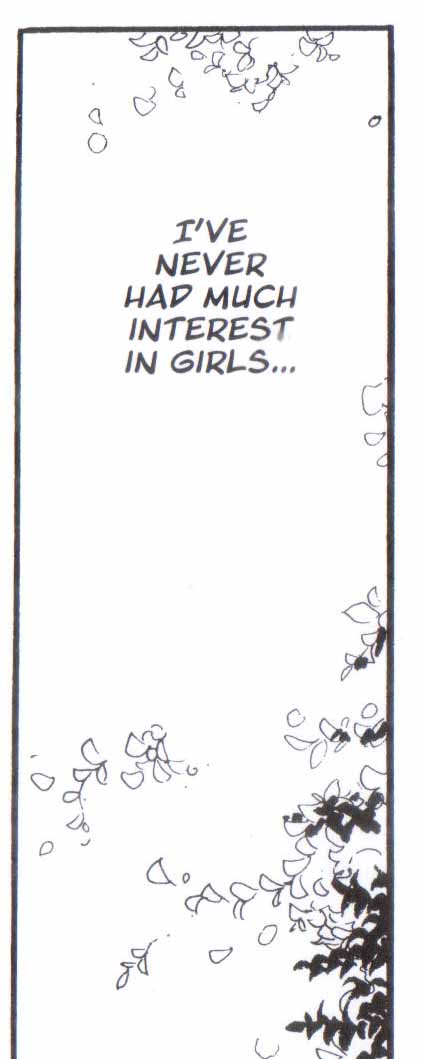

Apart for the tangy taste of forbidden fruit, is the love of one man for another any different than the much more familiar sight of a man and a woman pining for each other? As both the novel and film adaptation of Christopher Isherwood’s A Single Man suggests, the mere unfamiliarity of that object of affection is no hindrance to empathy. But just as truly great heterosexual romances remain in short supply in the medium (I’d be hard pressed to name more than a handful in manga and anime), so too does this rule apply to gay love in comics. Yet, to demand these standards of The Heart of Thomas is almost certainly a mistake for the comic in question was originally created for the enjoyment of women and has as much to do with the day to day issues of romance and gay love as the women in traditional harem manga have to do with flesh and blood females. Any resemblance to the gay liberation movement of the late twentieth century is simply good fortune if not purely coincidental. Some will say that the manga deserves praise because of its daring sexuality for its time—it is nothing less a seminal work in the boy’s love genre—but such a statement would be a demeaning admission that the comic is merely of historical interest.

The main inspiration for the manga at hand was apparently the film adaptation of Roger Peyrefitte’s Les amitiés particulières (novel published 1943, and film adaptation,1964). The similarities between the film and the manga are certainly striking.

There is the setting and sexual orientation of the protagonists as well as their relative ages. The lovers at the center of the film also struggle with ideas of purity and impurity (“It wasn’t his purity I loved.”) to the extent of expunging their sins of romantic (homosexual) love at confession. As with the final note left by Thomas, the letters between the young lovers act as erotic talismans. In the film, the letters are linked to the legend of St. Tarcisius—a young boy who defended the Blessed Sacrament with his life. These pieces of paper become nothing less than the body and blood of Christ to the lovers (they are certainly held in higher regard). Then there is the younger lover’s (Alexandre) suicide by jumping from a railway bridge (in this case, while traveling on a train) and the confusion of accident and suicide made more pressing in the film than in the comic because of the intransigent Catholicism which hangs heavy over the events.

While the love affair depicted in the film is not entirely convincing, it is certainly far more effective than anything found in Hagio’s comic. Peyrefitte’s work is restrained and classical in approach, and altogether more serious and real, especially in the interaction of the boys and a liberal minded priest named, Trennes. The priestly test commanded by Father Lauzon of the older lover (Georges; Juli’s counterpart) is nothing less than an act of temptation on the part of Satan. Hagio, of course, takes an alternative route. One might call it a disavowal of authenticity in setting, conversation, religion, and, perhaps, even sexuality—all of these becoming as putty and playthings in the authoress’ hand. A perfectly acceptable approach except for the decisive failure in delivery and communion.

The Heart of Thomas is in certain ways a sequel to the film, a fitful re-imagining of everything that could have been, but the final page of this book presents itself as a consummate evocation of my state of mind as I flipped through its pages.

The work was not clever enough, not brazen enough, not idiotic enough, and simply insufficiently well wrought to provide me with even a moment’s pleasure. It was, in short, interminable.

I have somewhat mixed feelings about Heart of Thomas (which I think you pick up a bit from my review.) I definitely enjoyed it more than you did though.

One interesting thing is that some of the points you hate were actually bits I rather liked. For instance, you seem to think that the scrambled/confused European setting is a downside, whereas I quite liked the reverse Orientalism; the way Europe (rather than the East) was transformed into a fantasy.

I’d also argue that translating or swapping the genders of the narrative changes the source material considerably, and so it’s not derivative in quite the way you’re claiming.

Pingback: MangaBlog — The History of Shonen Jump, told by one who was there

Pingback: Comics A.M. | ‘This is not a colorists thing’; GNs as learning tools | Robot 6 @ Comic Book Resources – Covering Comic Book News and Entertainment

“….whereas I quite liked the reverse Orientalism; the way Europe (rather than the East) was transformed into a fantasy.”

Could this be your white liberal guilt speaking? Why should a Japanese woman’s fetishization of Germany and gays be any better than a white man’s fetishization of Arab-Asian harem women/slaves. It’s just less offensive possibly.

In any case, I just found the book overlong for the threadbare plot and ideas. Maybe it would have worked at half its length or less. It certainly seems more messy and superficial than an Enid Blyton St. Clare’s book (or what I can remember of them).

I don’t think it’s white liberal guilt. A trope reversed and played with is more interesting than a trope that just sits there dead. Flipping the gaze — making European men the spectacle, and women the spectator — is playing with gender possibilities and with tropes of imperialism. It’s funny and surprising and thoughtful, at least to me.

Haven’t read Enid Blyton St. Clare, so can’t speak to that! I did enjoy this in your review though:

“Still others might see everything which follows Thomas’suicide as the fantasy of a collapsed mind, the tangled memories and imaginings of a dying brain hoping for a happy corrective to a tragically short life.”

I like that reading a lot.

“Could this be your white liberal guilt speaking? Why should a Japanese woman’s fetishization of Germany and gays be any better than a white man’s fetishization of Arab-Asian harem women/slaves. It’s just less offensive possibly.”

IMHO, it’s important and valuable that things such as Orientalism/reverse Orientalism/racism/sexism/etc. can be recognized and acknowledged for what they are.

However, honestly, I’m definitely not interested in the tedious process of using these labels as a truncheon to bludgeon work produced in another era. (“BAD art! Bad, BAD art!”) It’s an intellectual exercise for its own sake, a ritual of the university system that tends to end up with the critic denigrating the function of art itself, and only ‘allowing’ art which aspires to absolute social realism above all else. As an example, I’m reminded of the excellent-but-very-tedious-in-this-way book “Idols of Perversity” by my former college teacher Bram Djikstra, which examines and picks apart Victorian & Edwardian artwork for its degrading and demonizing images of women. The book’s fascinating. The examples are fascinating. The level of research, and the insight Djikstra gives into the times he’s writing about, is commendable. And, despite the fact that we’re supposed to look at it all as examples of sexism (which they certainly embody), the art is great. But in the end, the whole thesis of the book is “art sucks.” According to this attitude, art must only be a reflection of the (conscious or unconscious) neuroses and prejudices of its time, hence, f*ck it, unless it’s propaganda for ‘correct’ attitudes.

IMHO, in contrary, there is a “fantastical”, personal & psychological realism which is just as valid as social realism. Something can express the ‘true’ feelings and fantasies of the author/artist, or of their society (stereotypical or prejudiced as they may be), while not reflecting the actual social reality of the situation. The completeness and clarity with which personal views are expressed (and, hopefully, the originality with which they are expressed and combined) is valid in a separate sphere from analyzing whether their views bear any relation to social reality. I mean, really, it’s fun & illuminating to poke apart Hemingway’s sexism or Lovecraft’s racism, but who cares whether an artist smoked cigarettes, etc.

Anyway, with regards to “Orientalism”, all cultures exoticize or demonize other cultures, just as all human beings exoticize or demonize other human beings, whether based on outward characteristics or just the fact that they’re separate entities and we can’t read their minds. Such is life. The Other is The Other is The Other. It’s perfectly natural that any country’s media is (in general) going to look at other countries and cultures this way. Since Japan is a big media producing/consuming society it’s naturally going to be producing lots of images of The World Through Japanese People/Artists’ Eyes, just as the US does. Of course, when such attitudes in art can be traced to, and reflected in, actual real-world ABUSES OF POWER — US foreign policy as seen through Chuck Norris’ “Delta Force”, for example — then THAT’S important and those interconnections are very worthy of pointing out and criticizing. But Japanese people oohing and aahing over some idealized glowing romanticized European world doesn’t reflect itself in invasions or wars or perhaps really anything other than taking photos of blonde German tourists.

Anyway, forgive the rant. But basically, I find this line of thought very easy to take to an extreme which deprecates the function of art within society and denies the IMHO unavoidable subjective nature of the realities everyone carries around inside their heads. It’s been awhile since I’ve taken art classes or critical study so I don’t know what the counterargument is to the idea that this attitude, generally, is anti-art.

BTW, for what it’s worth, I did find “Heart of Thomas” slow at times and not as good as “They Were Eleven” or some of the short stories in “A Drunken Dream.” Maybe I’m giving it free points for its historical significance, a problem I have sometimes, or maybe I’m comparing it to all the zillions of awful Boy’s Love which came after, above which, on the whole, it generally shines. The first-of-the-formula is always fascinating.

Actually, I’m not offended in a “political” sense by the harem genre (in any shape or form). I just find this particular iteration to be rather bland and disconnected.

By the by, when I was in Germany recently, the most Japanese tourists I saw were along the Romantic Road (Rothernburg in particular) – a route devised by travel agents apparently but made popular by the various manga connected to it. Don’t know if that’s the *real* Germany though.

Jason: “IMHO, in contrary, there is a “fantastical”, personal & psychological realism which is just as valid as social realism. Something can express the ‘true’ feelings and fantasies of the author/artist, or of their society (stereotypical or prejudiced as they may be), while not reflecting the actual social reality of the situation.”

Of course, why would I disagree with this? Kafka is the most obvious example, and then there’s Philip K. Dick(?), and I suppose Gene Wolfe working through his Catholicism in The Book of the New Sun etc.. It’s just that if you’re going to opt for fantasy, there should be some reason for it and afford more avenues and depth than a realist approach – which Heart of Thomas doesn’t. It even fails at the level of pure entertainment in my opinion.

Noah: Does Kinukitty prefer Heart of Thomas to all the other Boy’s Love manga she’s read?

Is nobody going to mention how awfully kitsch the art is?

A bit too obvious? I think the main reason is that its par for the course as far as shoujo art of that era (and actually occasionally nowadays) is concerned? I think I sort of covered it by calling the entire experience an exercise in camp. Mind you, I didn’t scan Hagio’s depiction of some angels which would probably have made you vomit.

In any case, I thought kitsch was being rehabilitated in general. I think it’s seen as an absolute good in this subgenre.

Jason, for me at least thinking about how a work deals with political and moral issues is definitely what I come to art for, in part at least. And…a lot of art really does suck. I don’t think that it’s anti-art to point that out (quite the contrary, actually.)

Suat, Kinukitty doesn’t have much interest in 70s-80s BL books, as far as I can tell. I don’t think she much likes Hagio’s art style either.

Which brings me to Domingos…the art is definitely melodramatic/kitsch. I think it’s also quite smart about the comics form, though (the way the doubled characters, and the theme of memories-as-avatars-as-copies, is linked to the comics repetition of images.) And…it’s pretty clearly supposed to be camp, right? The trashy surface of eroticized boys is the lie (the story is about boys) which tells the truth (that the story is about boys) by flamboyantly broadcasting it.

Suat, to respond to something in your review…I don’t think the abuse is supposed to be surprising, exactly. Hagio isn’t about surprise for the most part; it’s about over-determination. The abuse in the comic is everywhere; not just in what’s done to Juli, but in the hyperbolic melodrama and pain throughout the work, with everybody’s parents falling over dead, in the sexualized panic attacks, etc. etc. As I tried to say in my review, in Hagio emotions and trauma aren’t tied to individuals; they’re more a background, or a substrate which pushes out into various people or situations at various times. That’s the point of the fantasy and of the kitsch patina, I think. The milieu isn’t real; it’s just a not very convincing surface over trauma.

Or that’s what I get out of it when I enjoy her work, anyway. Which I did for the most part on Heart of Thomas, though not unreservedly so.

Sorry for the off-topic ramble. Ng, I totally understand that your criticism of “The Heart of Thomas” is about its value as art (and entertainment) and not on a political level. As for the rest of my ramble, clearly I’m still working out issues about my old college class… -_-;; The discussion of whether one Orientalism is more ‘offensive’ than another (or the suggestion that all forms of Orientalism are innately offensive, which reduces the word ‘Orientalism’ to a synonym for ‘bad’) just pushed a button.

Within my privileged 1st World Bubble, in which I’m not actually being victimized by any external country or culture, I’m personally fascinated by seeing exoticized images of “The West” produced from other cultures, manga especially (though I really need to read a full translation of Qutb’s anti-Western travelogue in America)… maybe it’s just an expanded form of narcissism. I think that one reason many Western readers — and by “many” I of course mean “myself” but I’m assuming that some other people think the same -_- — go to manga, in addition to its value as pure comics, is the fascination of absorption in another culture where different values apply. (Perhaps as Dave Sim put it, when he dissed psychiatry, calling it “an invention of an alternate form of morality.”) So, in these faux-European manga works, it’s especially interesting to see the mirror flipped yet again, and see exoticized images of something I associate with as ‘familiar’ (not that I’m European, so it’s actually exotic to me too) reflected through the prism of exoticism that I unavoidably associate with manga. (Of course, I don’t just seek out ANY depiction of American or ‘Western’ subjects in manga: I’d certainly rather read Hagio’s Europe 100 times over than read Heroman or Tiger & Bunny.) Hagio is, I think, smart enough to realize that she’s doing this, and to make it all sort of a dreamworld of European tropes, rather than aiming at ‘realism’.

I don’t see camp above at all, high or low. Maybe there’s camp in those who follow her today, I don’t know (?), but since she was a pioneer, or so I’m told, what I see above is kitsch pure and simple.

Rehabilitating kitsch is impossible because kitsch is unconscious. If you know that it is kitsch and you like it just the same you transformed it into camp. Which brings us full circle to some of Hagio’s defenders, I guess…

On the other hand there’s the little detail of the feminized male body… (Which is what people think about when they thing about camp.) We could go there too, I guess, but from what I see above, it’s not over the top enough to the point of camp. Mileage may vary, though…

Intentionality’s always hard to parse…but I think Hagio is a pretty conscious creator, in general.

I was just talking about reception, sorry I wasn’t more clear. Kitsch can be produced in a very conscious way being the creator cynical about his/her own work. You can see that in Robert Altman’s The Player.

Going a bit off of Jason’s comments, I suppose I don’t see a pressing point to be made from “a case against Heart of Thomas”. If the work being discussed is doing neither harm nor good then it feels like the purpose of such criticism, if it is not to discipline “bad art” but rather to account for a work’s failure to entertain, mostly serves to differentiate the tastes of the critic from those who would find this comic worthy of time, consideration, appreciation, etc. flaws and all. If the critic is sincerely unmoved, what about this work merited such a lengthy disquisition? I feel like this is why a denial of “disciplining bad art” as a motive for this piece is being met with some skepticism.

As for Domingos’s appraisal of the art as “awfully kitsch”… again, I suppose I don’t understand what function is being served by that critical distinction. Is it therefore “bad” and worthy of our derision for not meeting some unspecified set of aesthetic criteria? Is this supposed to be a more neutral kind of formal categorization? If it’s not to your taste, that’s cool and all, but is there an argument you’re trying to make beyond that?

I’m sorry if I’m just coming off as rude or curmudgeonly here, I just feel a bit frustrated because it seems like works of this sort are all too often elaborately dismissed rather than productively argued against (or with, or through, or whatever.)

There’s a lot of discussion on this site of the purpose and/or value of negative criticism, actually. This is maybe my fullest discussion of why hate has value.

Let me say, Noah, that I was and am not trying to make an argument against negative criticism. In fact, the parts I most enjoyed from your and Jason’s reviews of HoT (lol) were the less-than-laudatory moments. I still believe that criticism, even as it makes a case against a particular work, needs to be making a case FOR itself. What bugged me about “Heart of Tedium”, was not its “negativity” but rather its dispassionate, summary dismissal. To analyze a work primarily through its failure to measure up to “great” works or figures which have addressed the same or similar themes feels like an abdication of critical responsibility before the criticism has even begun.

As for criticism’s “positivity bias”, this seems a bit of a boogeyman to me. Except where some mass consensus is completely silencing all critically divergent viewpoints, I don’t believe that standing against popular opinion to say “naw, that thing you value is actually bad” is adding anything more to the conversation than “the others'” supposed unthinking positivity. If good criticism appears to skew toward “the positive”, I think that’s because the critic is making an effort to find some productive way of discussing or thinking about the work, even if they didn’t particularly like it. Both the dislike and the “here’s what you might get out of it” can be made plain in the same piece and I don’t think criticism is enhanced by removing the latter for potentially obscuring the full extent of the former. For example, I didn’t get the feeling from your previous writing on Hagio Moto or your most recent piece on HoT that you’re particularly jazzed about her work and yet you still outlined plenty of interesting ways to think about/through it. Is this some kind of crime against the reader because your writing, by pulling out these points of interest despite your lukewarm reception of the text, may have deceived the audience into believing that the work is “better than it really is”? Perhaps only if you feel that by doing so you’ve committed an act of intellectual dishonesty, but as far as the reader is concerned I think that they’re more than capable of making that distinction for themselves (just as Hagio is perfectly capable of choosing this art style as a means of effectively/affectively expressing her ideas rather than simply glomming onto it naively or *shudder* apathetically.)

Well…I have mixed feelings about Hagio overall. Some of her comics are among my favorite comics by anyone ever…some I don’t like at all…and some (like Heart of Thomas), there are things I like and things I don’t like.

I certainly don’t think positive criticism is bad or anything; there’s lots of great positive criticism. I do think people are more comfortable writing about things they like in general…and that there’s a bias (especially in America, perhaps) against negativity, often.

I do think that one of the main ways we think about art is through comparison. And there are several things in Suat’s piece that seem provocative or interesting to me (as I mentioned above, the suggestion that the whole book is essentially a traumatized dream seems like an interesting reading — not least since the dreamer could be Hagio.) But obviously mileage will differ in this as in all things….

Yeah, I don’t mean to be overly harsh in my own critique–I did find interesting points and claims throughout this piece such as the dream reading–my problem was more with the overall majority of its efforts (including its references to other works and thinkers) seemingly being focused towards a dismissal of HoT on the grounds of its “failure” to be a “great work”.

The whole kitsch jab on the other hand, which Ng had nothing to do with, just gave me the heebie-jeebies. (Heebie-jeebies here being a polite euphemism.)