Just wanted to mention that I’m friends with both Lilli and Derik, but somehow writing about their work here it seemed weird to use their first names. So I didn’t. Hopefully they won’t be offended!

_____________

A bit back I talked about Bart Beaty’s claim that comics have been culturally gendered feminine in relationship to high art. As I said in my post, I don’t find Beaty’s argument entirely convincing. In the first place, high art is itself often gendered feminine (and often mocked as such.) And, in the second place, after thinking about it more, it seems like comics are more often associated with children than with the feminine per se. Children are, of course, often associated with femininity themselves, since traditionally raising children is women’s work and also because anything not-man (whether it’s women, boy, girl, or a horror-film pile of undifferentiated slime) often gets lumped together as “feminine.” Still, it seems worth noting that comics’ femininity seems like its arrived at through a series of somewhat abstracted substitutions. In terms of culturally coded femininity, comics isn’t needlepoint.

Still, just because comics aren’t usually directly associated with femininity, that doesn’t mean that artists can’t treat comics as feminine, or play with the idea of comics as feminine.

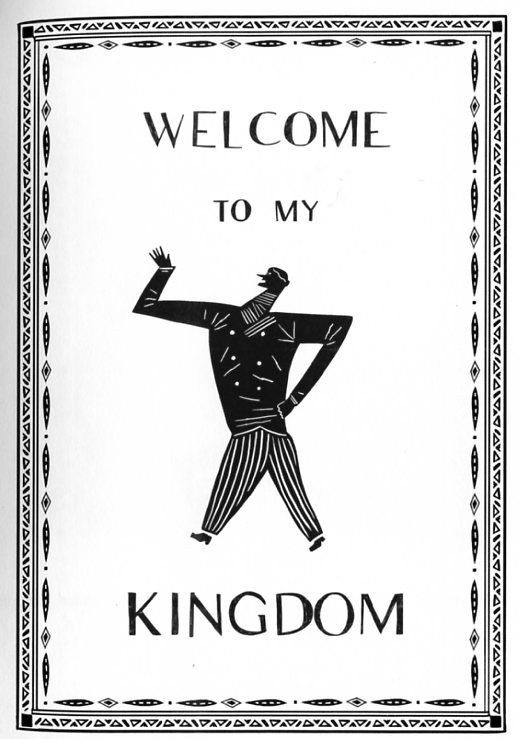

For example, consider the short story “Kingdom” by Lilli Carré, included in her recent Fantagraphics collection Heads or Tails. The story starts off with a well-dressed fellow celebrating his expansive masculinity inside a high-art picture frame.

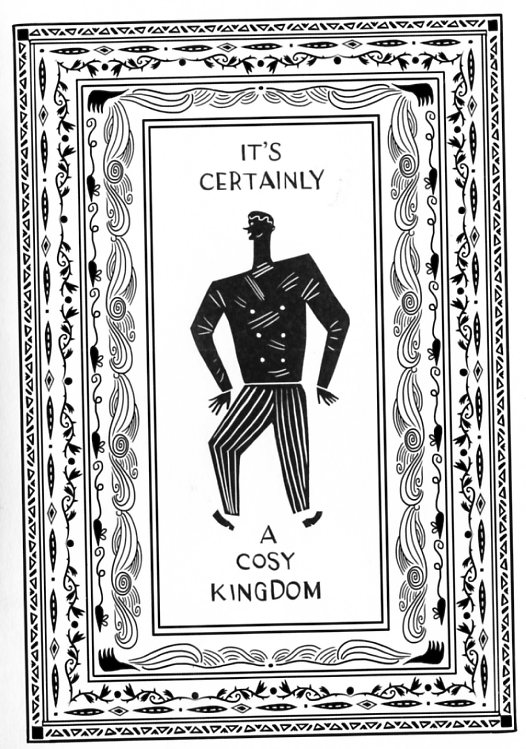

Page by page, though, new detailing and fringes are added to the inside of the frame, till the wide masculine range becomes a hemmed in, overly-crafted cozy feminine interior

And finally the man himself is reduced to a stylized decorative element. Instead of master of all he surveys, he is an object — or, rather, a surface, surveyed.

Again, the border here looks, and is surely intended to look, like a picture frame, and so the shuffling of gender is also a shuffling of the gendered connotations of fine art. On the one hand, high art is (as Beaty says) seen in its performative, striding creativity as a masculine kingdom — a canvas over which total control can be exercised in the interest of totalizing self-expression. At the same time, though, the detailed handwork and patterning associated with art — its prettiness, or fussiness, or surfaceness, or frivolousness — links it to the femininity of the craft fair.

If art is both hyperbolic masculine swagger and small-scale feminized detail, though, for Carré the form that mediates between the two is something that looks a lot like comics. The border in Carrés story is a frame…but, from page to page, it’s also a panel. So, on the one hand, the progression of the story could be seen as going from the least-decorated, most comic-like panel at the beginning to the most-decorated, least comic-like panel at the end — or, alternately, the initial image could be seen as a single picture frame, while the additional images emphasize more and more the sequential comic nature of the story. Thus, comics can be either a masculine form feminized by high-art frippery…or a feminine form which pulls high art down into the crafty feminine repetition of surface details.

Carréis herself a female artist who works in both the traditionally male-dominated art world and the traditionally male-dominated comics world. As such, she is, it seems, gently tweaking the masculine pretensions of both — or perhaps tweaking her own attraction to the masculine pretensions of both. That tweaking is performed in part by deploying comics as the feminine alternative to high art — and high art as the feminine alternative to comics. Both comics and high art, in other words, are only nervously, unstably masculine, and that instability is, for Carré, not so much a danger or a weakness as it is a potential — a way for masculine and feminine, art and comics, to open out and lock together in a single claustrophobic, vertiginous spiral.

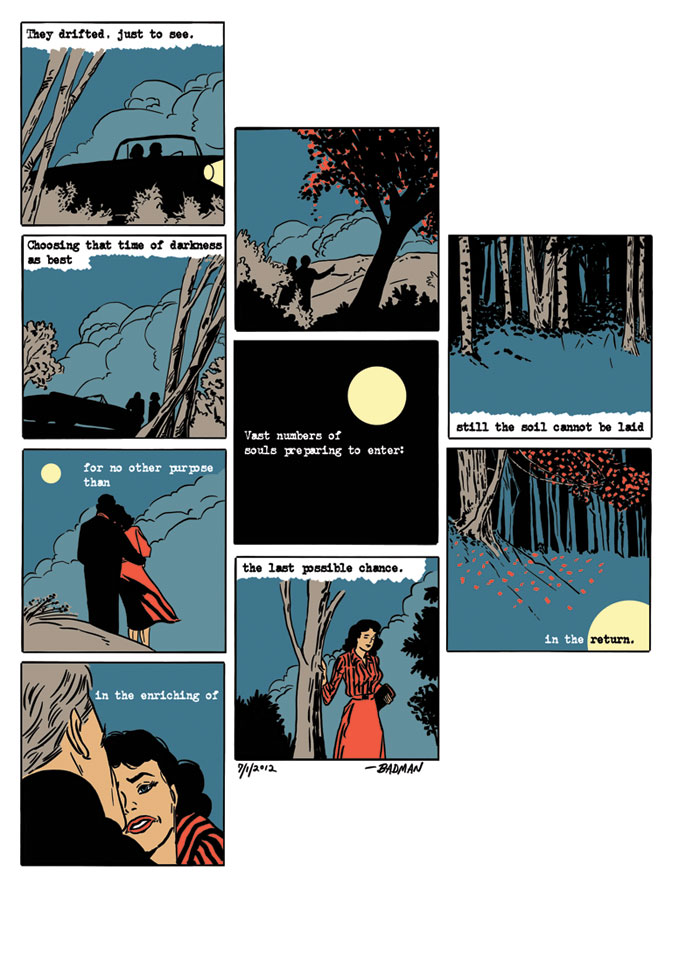

Derik Badman takes a very different approach to comics as feminine. In the anthology Comics As Poetry, Badman channels pop art in a series of ambiguous pages.

Lichtenstein mostly used single panels drawn from comics for his canvases — he ironized melodramatic narratives by pulling single moments out of them, and so highlighting their generic artificiality. There’s a little of that in Badman’s version too; the off-kilter columns of images make the narrative flow uncertain — the panel sequence is almost arbitrary. You can read left to right or top to bottom, or even in some sense randomly around within the page.

Again, you could argue that the effect here is something like mockery and something like appropriation; taking the feminized tropes of romance comics, hollowing them out, and presenting the remains as a de-emotionalized, high-concept masculine avante garde. As I’ve written before, though,I think that reading does a disservice to Lichtenstein, and I think it’s not really fair to Badman either.

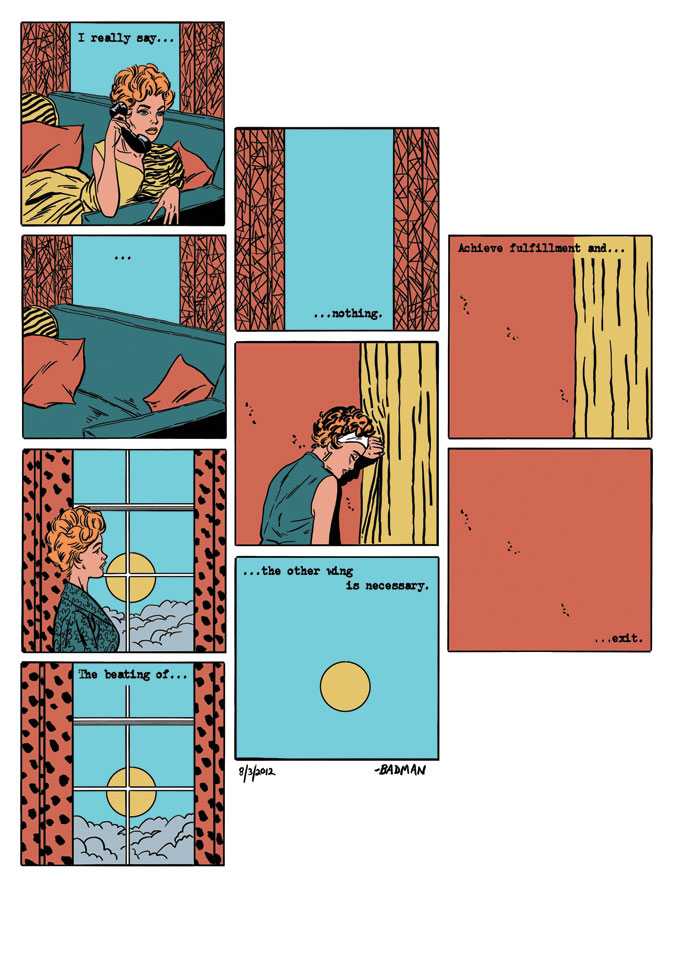

Rather, in Badman’s case, it seems less like the high art avant garde masculinizes the melodrama than like the melodrama reveals the true, feminized emotionalism of the avant garde. In the page below for example:

The first panel, with the telephone, becomes a kind of synechdoche for the entire page, thematizing an illustory connectedness which emphasizes a greater absence or distance. The ellipses trailing off or trailing in, to which panel or from which panel is never clear, similarly hesitantly underline the way each panel comes out of and goes into white space…comics not as Charles Hatfield’s art of tensions, but rather as an art of slack disconnection. The desire to make meaning of the narrative — to have “The beating of” connect to “the other wing” — is also the desire or loss of the woman — or perhaps of the women, plural, since the identity of multiple images is one of the comic conventions of continuity that here breaks down into the overarching convention of discontinuity. Comics multiplies bodies, and multiple bodies is desire. The avant garde lacunae, the resistance of interpretation, becomes, not anti-narrative cleanliness, but — through the mirror of comics’ formal elements — a hyperbolic extension of narrative’s most febrile excesses of deferment and longing.

Badman, then, seems to out-Beaty Beaty, inasmuch as, in this reading, comics is not just culturally feminized in relation to high art, but is actually, formally feminine. Indeed, that formal femininity is so overwhelming that it starts to absorb not just comics, but everything connected with comics — not least of all Pop Art. Badman’s comics almost demand to be viewed, not as cut up panels of comics, but as conglomerations of pop art images — and in creating those conglomerations, he makes it hard to see pop art as anything but conglomerations. Lichtenstein’s canvases…are they really isolating images from a narrative? Or, instead, are all those isolated images trying but failing but trying to talk to each other, so that all of Roy Lichtenstein’s panels end up, not as bits from different comics, but as their own single melodramatic discontinuity? For that matter, when you go to a gallery or a museum, each piece isolated in it’s own frame — doesn’t that isolation, that disconnection, that yearning gap, make the high art more comics than comics, and therefore, formally, more feminine than feminine?

For Badman, as for Carré, then, the binary art/comics doesn’t so much map onto the binary masculine/feminine as it creates an opportunity to think about binaries and gender. In the work of these two creators, comics and art want each other and want to be each other and want nothing to do with each other, and certainly too, are each other. So, too, does male/female close in upon itself and empty out of itself, a folding, unfolding box holding and releasing form and desire.

A deceptively simple (perhaps deliberately cliched?) title to a fascinating post, Noah. I get tangled in the logic of the final paragraphs, and a bit skeptical about the overarching feminine/masculine metaphors as ways of describing entire artistic traditions, but I dig your readings of Carré and Badman. Provocative stuff!

Thanks Charles! And yeah, the title is me being cute, perhaps overly so.

In the conclusion, I’m trying to say in part that I don’t really think it makes sense to describe entire artistic traditions as feminine or masculine, necessarily. I think instead they get figured in different ways at different points…and I think both Lilli and Derik are playing with masculine/feminine and comics/art in various ways. I think the binary comics/art, as a binary, ends up being a useful, or provocative, or aesthetically meaningful way of talking about masculine/feminine. And for me, one of the most interesting things about it is that comics/art isn’t stable, and isn’t in a lot of ways a contrast; comics and art can be like each other, or can even be each other. Which can also be true of masculine/feminine. And the reason masculine and feminine appeal to each other or desire each other or repulse each other is not just because they’re different then, but because they’re alike — which, again, can be seen also as true of comics/art.

And again, the point isn’t that comics/art maps onto masculine/feminine or feminine/masculine, but that it can map onto either, depending on how you think about or set up the terms.

Not sure if that cleared things up or made them more garbled, but….

Oh…also wanted to mention that the tile of Lilli’s piece is “Kingdom” not “Freedom”. I changed it in the post. The initial flub was caused by the fact that I have no editor and am also an idiot.

Great post, Noah! I especially love this section, which would make for a great essay all its own:

“For that matter, when you go to a gallery or a museum, each piece isolated in its own frame — doesn’t that isolation, that disconnection, that yearning gap, make the high art more comics than comics, and therefore, formally, more feminine than feminine?”

Also…could it be that the word/image interplay in conventional comics narratives reinforces some sort of male/female binary (Hillary Chute alludes to such a binary early in her book, at least as I read her intro), whereas comics which dispense with, for example, panels or grids challenge that binary?

I’m thinking of Edie Fake’s Gaylord Phoenix (speaking of another artist who works in comics/zines and in gallery shows and eliminates panel borders in some of his work) or maybe some of Chester Brown’s work where he dispenses with panel borders…

Huh. That’s interesting. I think it would certainly be possible for a creator to use the words/image binary in comics as a way to talk about male/female binaries. Does Edie do that? I don’t know…I guess I’d have to think about it….

I’m reading this thing by Boris Groys, who writes for E-Flux, about how design (meaning anti-design) became the new expression of the soul after the death of God, with aesthetics coming to stand in for ethics; he cites Adolf Loos’ “Ornament and Crime,” about how you can’t trust anything that’s too embellished.

So, that women would then explore the jouissance of formalism narratively, while men do so in images, makes a lot of sense. Roy Lichtenstein masculinized the nostalgic sentimentality of romance comics by chopping them up, and Badman made Pop Art feminine by stringing the pieces back into a stitched-together sequence.

So Lichtenstein deflated the ineffability of love, and Badman deflated the solipsism of spectatorship. Or something.

“Roy Lichtenstein masculinized the nostalgic sentimentality of romance comics by chopping them up, and Badman made Pop Art feminine by stringing the pieces back into a stitched-together sequence.”

I really like that reading.

Bert, do you have a link to the essay you mentioned? Sounds interesting.

As for Edie’s work, that questioning of the male/female binary in Gaylord is an exploration which seems to begin at the level of form–pages without panels or traditional text boxes, for example–and then grows into a meditation on the gender fluidity of the characters themselves, especially the hero of the book.

What’s interesting is that in one of his newer zines, Sweatmeats #1, he’s using panels, but not in a grid–usually two per page, yet he’s still exploring many of the issues in Gaylord, at least in my reading of it. And of course the design is impeccable as always, but the images themselves are more harrowing than anything in Gaylord.

And then what happens in a book like Martin Vaughn-James The Cage–where there are words and images, but no apparent characters or subjects in any of the frames?!

Also really looking forward to reading the two pieces you wrote about, Noah. I love the design work on the Carre pages.

Here’s the Groys link. Enjoy… http://www.sternberg-press.com/index.php?pageId=1296

Sorry I’m too dumb to embed links in words.

“a de-emotionalized, high-concept masculine avante garde”

I sure hope my pieces don’t come across like that… I’ll take avante garde, at least in respect to comics if not to Art, but I personally don’t find the pieces de-emotionalized, I prefer to think of them as re-emotionalized.

I’d agree with “re-emotionalized.”

Yeah; as I say in the piece I don’t actually think that’s what’s happening Derik. I hope that was clear.

Noah: I wasn’t sure if you were saying “it could be this, but it’s also this” or “you could say it is this, but I disagree, rather it is this.” If that abstraction makes any sense.

No mockery either. I really do like the visuals of these old romance comics. I’ll admit a certain contrariness is using only images from Vince Colletta, a man who I only ever heard about because people say he ruined Kirby’s drawing, but I think his images are way more interesting than Kirby’s.

Yeah; definitely more the second in my view. Though I think a little irony bleeds through; it’s hard to be working off of pop art without getting any of that. (Which isn’t a bad thing, to my mind anyway.)

Lilli Carré’s “Kingdom” is pretty splendid; can’t help but be reminded of this famous series of cat paintings…

http://api.ning.com/files/gbCwImToiNoTPz-nqf3tjy2XJiJuno9DZD0qw9iTl2IXHSFcH7rfVWOq4Hy*ZhPEZRJmeCn6d444yJiuMVlU9mW9oYUa4lND/l.w.catsprogresslg..jpg

…by Louis Wain, an artist who was moving deeper into schizophrenia.

(More Wain: http://www.schizophrenia.com/pam/archives/004232.html

http://mayhemandmuse.com/the-schizophrenic-psychadelic-art-of-louis-wain/ )

Indeed, Carré brilliantly shows how an accumulation of possessions, and the rectilinear walls to protect those possessions, can entrap, constrict. Note how the expansive body-language of a boulevardier ends up scrunched; his body not even touching the ground!

Forcing the work (and others that follow) into the Procrustean bed of masculine/feminine roles (you’d think it was a Rush Limbaugh, Bible-thumping acolyte maintaining such simplistic “art is nonmasculine, faggy” interpretations) is, however, utterly absurd.

Might as well shove Marxist interpretations upon the works covered here, or attack them as “racist” or “Eurocentrist,” “able-ist.”

And it’s ahistoric: why should ornamentation and elaborate patterning, rococo embellishment be “feminine,” when it was the standard rule of décor for wealthy, powerful, warmongering and brutal rulers in the past?

Rather, what those patterned, ever-expanding borders most exemplify is artificiality, control: the graphic elements look the equivalent of soldiers marching in formation.

As for Badman’s comics showcased here making “comics is not just culturally feminized in relation to high art, but…actually, formally feminine,” why so? That two of his stories (excellent, BTW) feature women in stereotypical “romantic” situations somehow feminizes the entire art-form, including oh-so-girly stuff like “Blazing Combat,” “The Vault of Horror,” “Crimebusters” comics?

(Not sure if the last title existed; looking up the name to confirm, ran across: http://dangerousminds.net/comments/he_she_the_most_cunning_vicious_and_fiendish_killer_of_all_time )

Did anyone else notice that the first “feminine” Badman comic might feature…a murder? Two enter the forest, only one leaves. The shot of the moon reminiscent of those “cutaway” shots directors use to shy away from depictions of violence. In the last two panels, the red leaves appearing on the ground suggest an outpouring of blood.

Mike, I like your readings. I don’t really see why they have to preclude mine?

Now I can’t help myself– Lilli’s frame comic totally looks like a person turning into a vagina. Did anyone mention that yet?

Heh. That’s pretty great…and no, I totally hadn’t caught that.

————————

Noah Berlatsky says:

Mike, I like your readings. I don’t really see why they have to preclude mine?

————————–

They don’t. This is art, not mathematics, so there isn’t necessarily (note the caveat!) any clear-cut “right way” to interpret a work.

In Hindu spirituality, there’s the saying, “many lights of different colors can all illuminate the same room” (at the same time)…

————————–

Lichtenstein’s canvases…are they really isolating images from a narrative? Or, instead, are all those isolated images trying but failing but trying to talk to each other, so that all of Roy Lichtenstein’s panels end up, not as bits from different comics, but as their own single melodramatic discontinuity? For that matter, when you go to a gallery or a museum, each piece isolated in it’s own frame — doesn’t that isolation, that disconnection, that yearning gap, make the high art more comics than comics, and therefore, formally, more feminine than feminine?

—————————

Surely, though, “disconnection,” isolation, are seen as more masculine than feminine. To an extreme, there’s the stereotype of the lone gunman who rides into town, disposes of the bad guys, and — though a woman has become attached and wishes he’d settle down and stay — rides off into the sunset at the end.

Why, even women’s brains are predisposed more for sociability, interpersonal connections:

—————————–

– Human relationships. Women tend to communicate more effectively than men, focusing on how to create a solution that works for the group, talking through issues, and utilizes non-verbal cues such as tone, emotion, and empathy whereas men tend to be more task-oriented, less talkative, and more isolated. Men have a more difficult time understanding emotions that are not explicitly verbalized, while women tend to intuit emotions and emotional cues…

– Reaction to stress. Men tend to have a “fight or flight” response to stress situations while women seem to approach these situations with a “tend and befriend” strategy. Psychologist Shelley E. Taylor coined the phrase “tend and befriend” after recognizing that during times of stress women take care of themselves and their children (tending) and form strong group bonds (befriending). The reason for these different reactions to stress is rooted in hormones. The hormone oxytocin is released during stress in everyone. However, estrogen tends to enhance oxytocin resulting in calming and nurturing feelings whereas testosterone, which men produce in high levels during stress, reduces the effects of oxytocin.

———————————-

http://www.mastersofhealthcare.com/blog/2009/10-big-differences-between-mens-and-womens-brains/

(Not that all males or females will act the same, but nature certainly pushes tendencies on the groups. And as I’ve written in the past, society routinely manipulates and exaggerates these and other tendencies: that men may be encouraged into becoming “cannon fodder,” women into exploitable, selfless nurturers.)

For all the romantic trappings of Derik Badman’s two superb comics stories above, the choppiness of the narratives and wording (echoing the fragmented, almost haiku-like way much modern poetry has gone), intrusively cropped “camera angles”…

(Echoes of http://goodcomics.comicbookresources.com/wp-content/uploads/2007/12/Steranko%207.jpg )

…expresses a fragmented, modernistic sensibility. It’s striking seeing in “period” movies the prevalence of group dancing; the better part of a whole community coming together as a unity, rather than atomized couples holding onto each other (and often not even holding!), ignoring everyone else except as necessary to avoid bumping into them, in more “modern” dances.

Here, even though a grid is superimposed, Frank King shows an entire community interacting: http://cdn.comixology.com/assets/26GasolineAlley.jpg . (A Hellish version at https://pulllist.comixology.com/articles/354/Exhibitionist )

Mike, I think isolation is stereotypically masculine…but yearning for connection would be stereotypically feminine. That’s part of why I think it’s possible to see Derik’s piece making masculine high art feminine, in a way….