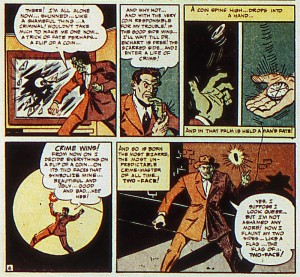

Bob Kane first drew the villain Two-Face in 1942 (Detective Comics #66). But it wasn’t till 2008 that the Nolan brothers got his origin right. My favorite scene from The Dark Knight is Heath Ledger’s Joker convincing Aaron Eckhart’s brutally disfigured Harvey Dent to embrace the dark side. How’s he do it?

With the flip of a coin.

Javier Bardem made similar use of a quarter the year before in the Coens’ No Country for Old Men. Live or die? Ask JFK and the eagle.

Rewind two more years, to Woody Allen’s 2005 Match Point, and Jonathan Rhys Meyers spells it out: “People are afraid to face how great a part of life is dependent on luck. It’s scary to think so much is out of one’s control.”

Meyers’ character (he later gets away with murdering an inconvenient lover) fascinated Roger Ebert because, like all of the characters in the film, he’s rotten: “This is a thriller not about good versus evil, but about various species of evil engaged in a struggle for survival of the fittest — or, as the movie makes clear, the luckiest.”

Bardem’s Anton Chigurh is a hitman, so at least he’s supposed to kill people. But that’s not what makes him so damn scary. The movie’s nihilism is contained in those coin flips. When Chigurh tells a gas attendant to “Call it,” the man says he didn’t put nothing up to bet. “Yes, you did,” Chigurh answers. “You’ve been putting it up your whole life you just didn’t know it.”

Myers’ tennis pro plays the same game: “There are moments in a match when the ball hits the top of the net, and for a split second, it can either go forward or fall back. With a little luck, it goes forward, and you win. Or maybe it doesn’t, and you lose.” Near the film’s end, when he tosses an incriminating piece of evidence (his dead lover’s ring) toward the river, it takes the same fate-determining bounce. He wins.

When the gas attendant wins his toss, Chigurh congratulates him and tells him not to put the lucky quarter in his pocket where “it’ll get mixed in with the others and become just a coin. Which it is.” Chigurh’s last victim already know this and so refuses to play: “The coin don’t have no say. It’s just you.”

“Well,” says Chigurh, “I got here the same way the coin did.”

The Nolans’ Joker embodies the same anarchic philosophy: “I’m not a schemer. I try to show the schemers how pathetic their attempts to control things really are.” And in the true spirit of anarchy, he points the gun at himself. “I’m an agent of chaos,” he explains to Harvey Dent as he leans his forehead into the barrel. “Oh and you know the thing about chaos, it’s fair.”

The Joker survives his coin toss too, but not Dent. He’s Two-Face now. He worships Chigurh’s god.

My wife and I were recently catching up on the last season of the British cop show Luther. It opens with Idris Elba (we liked him as a gangster in The Wire too) sitting on a couch, playing Russian roulette. He learned the game from a homicidal army vet, not the Joker, but his character is relinquishing his will to the same higher Non-Will as the others. Except Luther is a (mostly) good guy. So by the season’s end he’s traded in the gun (he rarely carries one anyway) for an ice cream cone with his newly adopted teen daughter. What got him there?

Not a coin toss.

It wasn’t a roll of the dice either. That’s the device of chance preferred by the season’s ugliest villains, a pair of identical twins (two people, one face) playing a real-world game of D&D. They earn experience points by killing people. You can do it anywhere, a gas station, subway, a lane of stopped traffic. Just open your backpack, spread out your bat, hammer, and squirt gun of acid, and roll the dice.

I bought our twelve-year-old his first D&D game this Christmas. (He learned about the game last year from a particularly hilarious episode of our family’s favorite sitcom, Community.) So while Luther’s evil twins were rolling their dice, our son was upstairs rolling his. I can now differentiate between the thump and skid of dice on floorboards and the smack and skitter of dice in a D&D box lid.

I asked him once, if instead of killing the various trolls and orcs and armored whatnots he has to battle, could he just knock them out, tie them up, and leave them for the authorities to incarcerate?

He said, “What authorities?”

Right. There’s no government in D&D. It’s literal anarchy. Even at the metaphysical level. There are plenty of supernatural beings, but no Supreme One. Gods but no God. Even the Judeo-Christian Lord is only the sum of the numbers in the Dungeon Master’s hand. And the DM isn’t God either. He (yes, in this case, DMs are almost as uniformly male as Catholic priests) must obey the Dice like everyone else.

Roll them to determine the whims of heredity, what skills and proclivities you’re born with, which you’re not. The Dice control every important moment of your life, every struggle, the literal blows of chance. Sure, my son admits to ignoring the occasional bad roll, but he said it gets boring if you do that too much. Real life is random.

So why is randomness overwhelming portrayed as “evil” in pop culture?

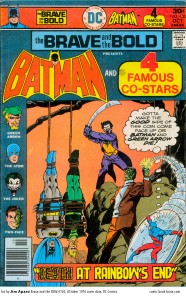

First time I saw Two-Face as a kid (October 1976, The Brave and the Bold #130), he bewildered me. Instead of just killing Batman and Green Arrow, he and the Joker flip a coin? (Allowing the Atom to secretly climb on and alter its fall.) At some point in the story, Two-Face betrays the Joker—and not because Heath Ledger killed his fiancé. It’s just what his quarter tells him to do. So why, my ten-year-old self wondered, is the guy considered a supervillain?

When those D&D twins bend down with a 20-sided die, only the ugliest options are in play. Shouldn’t your backpack have more than murder weapons? Where’s the wad of twenties for homeless people’s cups? Why does Chigurh only flip a coin when he’s thinking about plugging someone in the head? A true worshipper of chance would be Mother Theresa half the time.

So it’s not randomness that makes hitmen, supervillains, D&D players, and tennis pros scary. It’s the deification of randomness. The abdication of responsibility. A true nihilist (like Alan Moore’s Comedian) embraces the absence of God and so the permissibility of everything. But that’s an abyss too deep for the Two-Faces of the world. They can’t fill that God-sized gap with themselves. They can’t hack that much free will. So instead of randomness, they invent Randomness and pretend they’re just following order. Pretend that’s not really your finger on the trigger.

You can take comfort in the illusion that the bullet in Russian roulette chooses you. But an ice cream cone, that’s something you have to go out and get. It’s a scheme. You have to choose to want it despite the uncontrollable probabilities of your getting or not getting it. If life’s a crap shoot, the only question is how you cope with that fact.

I do know one writer who flips Randomness to make us see it not as a force of evil but of good. Or, more accurately, of helpful change. Glen Dahlgren’s A Child of Chaos spins a D&D-inspired world where the lazy gods of Charity, Evil, War, etc. have gotten a bit too complacent. What the universe needs is the smack and skid of a die. Literally. That’s the magic instrument of Chaos, how the promised one will restore some much needed disorder, unlock all that magic the privileged class keeps hogging. No more homicidal lunatics. Chaos is our hero.

Unfortunately you don’t get to read Dahlgren’s novel yet. My copy is a Word file in my laptop. The manuscript (like my own third novel) is still mid-spin in the seemingly random universe of the publishing industry. I’m rooting for the unmarred JFK side of the coin. But there are no guarantees. Right now my agent is battling the forces of Evil and trying to land my manuscript in a New York house. It’s a chaotic process (stalled by the randomness of a hurricane and jaw surgery so far), but the dice keep bouncing.

Glen and I aren’t complaining. Like Chigurh’s last victim, we understand the rules of the game: “I knowed you was crazy when I saw you sitting there. I knowed exactly what was in store for me.”

God bless chaos.

It sounds like Dahlgren has lifted the metaphysical struggle between “law” and “chaos” from Michael Moorcock. My impression of Moorcock’s work — I’ve barely read any — is that either that dichotomy is orthogonal to the “good”/”evil” dichotomy, or “chaos” is aligned with the “good”. Grant Morrison, no stranger to pilfering Moorcock, likewise lifts it in Kid Eternity.

But the most complete imitation I know of is actually Dungeons and Dragons itself.

I don’t think Moorcock aligns chaos with good…or not exactly, anyway. Long time since I read it, but Stormbringer who wins the Elric series is I think a force of chaos, and it isn’t good, really.

Well, there you go.

Now that I’ve thought about it a little more, though, I’m fairly sure that Morrison aligns chaos and good in at least some bits of his work, chaos representing growth and progress and order stultifying repression — thinking of e.g. bits of The Invisibles and Marvel Boy… It befits his general pseudo-dionysian style.

Marvel Boy is chaotic, hut he’s actually supposed to be from a fascist civilization.

In other words, if Marvel Boy won he would be a servant of order. It’s only because he’s on earth and his friends are killed that he’s chaotic, presumably.

Reminds me of another McCarthy entity, The Judge. Blood Meridian was all about how if you take chaos seriously, you end up with what most people would consider a pretty unpleasant state of affairs.

There’s a novel called The Dice Man about a guy who makes all his decisions with a roll of the die. I haven’t read it, but apparently it was a cult item in the 70s.

From reading Doom Patrol, I always felt Morrison’s indulgence in chaos was dependant upon accepting order as a heroic yet unachievable goal. All those logic-defying, reality-twisting villains like the Brotherhood of Dada are great fun, but they are ultimately antagonists. And though the Doom Patrol themselves also defy the tidy order of superhero logic (what with their gender-bending, split-personality, existential crises), our engagement with them always focuses upon their heroic attempts to bring some stability to their lives (even if they are doomed to fail).

But I think Morrison is hard to pin down in that sense. In Super Gods he talks about how he considers the public’s desire for revolutionary chaos and fascistic order switches periodically every decades or so and that he tries to change with it.

Seeing chaos and order as essentially arbitrarily chosen moral positions is kind of embracing chaos, though.

I mean, it’s embracing the market, but worshipping the market is worshipping chaos, pretty much. One of the reasons it’s so bizarre that the people who claim to be conservative are gung-ho capitalists in this country (and others). Capitalism doesn’t care about your traditions, y’all. It just wants to eat and gibber and party.

In Kid Eternity, Morrison explicitly has the hero an agent of chaos. He calls some chaos-generating devices ‘the fountains of creation’.

Moorcock pretty much establishes the forces of Chaos and Order as being both vicious and anti-human, each in its own way. The final victory in the Elric cycle is when Order and Chaos achiece Balance.

A splendid essay! Thanks for its pleasures…

A few tidbits:

On the way to work, I drive by what I presume is a church’s new sign, announcing the choice: “Dice or Deity”…

(Google’ing for more info, it deals with the Book of Esther, that sign put up by the hipster-looking church Element3 — http://element3.org/ — Izzat Grant Morrison a-preaching away?)

“God does not play dice with the universe.”

– Albert Einstein

Stephen Hawking said, “Not only does God play dice, but… he sometimes throws them where they cannot be seen.” (His “Does God Play Dice?” lecture at http://www.hawking.org.uk/does-god-play-dice.html )

——————

Chris Gavaler says:

So it’s not randomness that makes hitmen, supervillains, D&D players, and tennis pros scary. It’s the deification of randomness. The abdication of responsibility. A true nihilist (like Alan Moore’s Comedian) embraces the absence of God and so the permissibility of everything.

——————–

Speaking of “Watchmen,” another character from that great work likewise saw the randomness, and came to a diametrically different conclusion. After discovering the gruesome fate of the kidnapped girl he’d sought to rescue, leaving her murderer to perish in flames, Rorschach recalls:

——————–

Stood in firelight, sweltering. Bloodstain on chest like map of violent new continent. Felt cleansed. Felt dark planet turn under my feet and knew what cats know that makes them scream like babies in night. Looked at sky through smoke heavy with human fat and God was not there. The cold, suffocating dark goes on forever and we are alone. Live our lives, lacking anything better to do. Devise reason later. Born from oblivion; bear children, hell-bound as ourselves, go into oblivion. There is nothing else. Existence is random. Has no pattern save what we imagine after staring at it for too long. No meaning save what we choose to impose. This rudderless world is not shaped by vague metaphysical forces. It is not God who kills the children. Not fate that butchers them or destiny that feeds them to the dogs. It’s us. Only us. Streets stank of fire. The void breathed hard on my heart, turning its illusions to ice, shattering them. Was reborn then, free to scrawl own design on this morally blank world. Was Rorschach.

———————-

Emphasis added; from http://en.wikiquote.org/wiki/Watchmen

“The very meaninglessness of life forces a man to create his own meaning.”

– Stanley Kubrick

(The whole of Kubrick’s commentary at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/User:Zimbabweed )

The ancient Romans were obsessed by randomness, as embodied in the goddess Fortuna. Interestingly, the ancient Greeks, by contrast, were convinced of the omnipotence of an entirely opposite force: Fate, foretold destiny, which no being can escape.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TIQynsWpBpQ&feature=youtube_gdata_player here’s a relevant passage of Blood Meridian.

More recently, on the pro-chaos side, there’s the philosopher Quentin Meillassoux: “Our absolute, in effect, is nothing other than an extreme form of chaos, a hyper-Chaos, for which nothing is or would seem to be, impossible, not even the unthinkable.” (grabbed that quote from here).

Regrettably, we never got to see how Moore’s “Big Numbers” (originally to be titled “The Mandelbrot Set,” until Benoit Mandelbrot objected) would’ve panned out narratively…

——————————

Because of his access to IBM’s computers, Mandelbrot was one of the first to use computer graphics to create and display fractal geometric images, leading to his discovering the Mandelbrot set in 1979. In so doing, he was able to show how visual complexity can be created from simple rules. He said that things typically considered to be “rough”, a “mess” or “chaotic”, like clouds or shorelines, actually had a “degree of order.” His research career included contributions to fields including geology, medicine, cosmology, engineering and the social sciences. Science writer Arthur C. Clarke credits the Mandelbrot set as being “one of the most astonishing discoveries in the entire history of mathematics”.

——————————

Emphasis added; more at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Beno%C3%AEt_Mandelbrot

And apparently — there is a hit of this when a rendering of milk poured in a cup of coffee swirls abut in one of Mandelbrot’s fractal shapes — chaos theory would’ve played a part in the overall scheme:

—————————–

Chaos theory studies the behavior of dynamical systems that are highly sensitive to initial conditions, an effect which is popularly referred to as the butterfly effect. Small differences in initial conditions…yield widely diverging outcomes for such dynamical systems, rendering long-term prediction impossible in general.

This happens even though these systems are deterministic, meaning that their future behavior is fully determined by their initial conditions, with no random elements involved. In other words, the deterministic nature of these systems does not make them predictable…

——————————–

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chaos_theory

Thus, Order and Chaos are not necessarily mutually incompatible; where we see chaos, there might actually be an underlying order…

Mike,

Don’t give up on Big Numbers…You never know. Alot of those old projects keep coming to light (like the comics version of Fashion Beast currently being published).

Mike, great summary of chaos theory and the layers of chaos and order in the world. It also makes a thought-provoking response to Rorshach’s creed above.

Chris, my juvenile sense of humor requires that I ask: Is your agent pitching the book to Random House?

I enjoyed this essay. When I was a kid, the battle between chaos and order was a common theme in superhero comics, with the villains and heroes as pawns of those respective forces. I never understood why chaos was usually associated with evil and order for good, since totalitarianism and anarchy both have evil effects. You present a more sophisticated comparison, I think.

If Chigur is a villain because he deities randomness, is Rorshach a hero because he demonizes it? Is it even accurate to say he does so?

Going to get an ice cream cone now. Thanks for the idea.

Random House! That’s funny. And, yes, actually they are on my agent’s list. Wish me luck!