[Spoliers throughout]

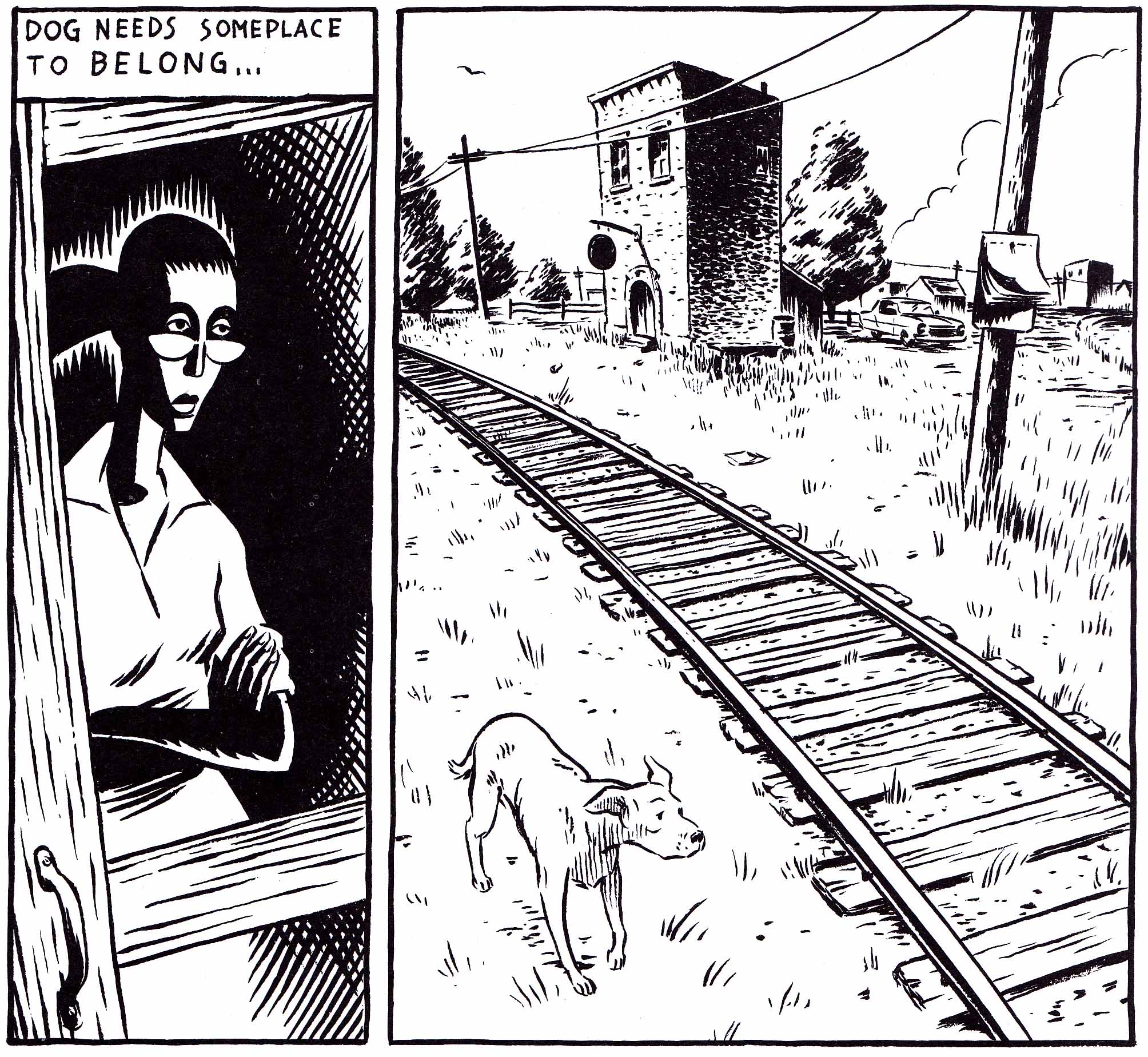

Twenty years is quite a length of time in the world of comics but it has been nearly that since Graham Chaffee last published a comic. Some old timers do remember him however, and he does retain a measure of respect for two books he drew back in the 90s namely, The Big Wheels, and The Most Important Thing and other stories. I wrote a review of those two publications way back then but I have to say I can barely remember what I wrote or even much about those books.

Of the cartoonists offering the author support on the back cover, James Romberger comes closest to the truth when he suggests an alternate history where the art form was not shuffled into a nether world of superheroics:

“…a book seemingly lost in time…his clean appealing storytelling and expressive brushwork evoke an alternative golden age of comics; an age perhaps in which superheroes never existed and the medium told more straightforward, poignant stories.”

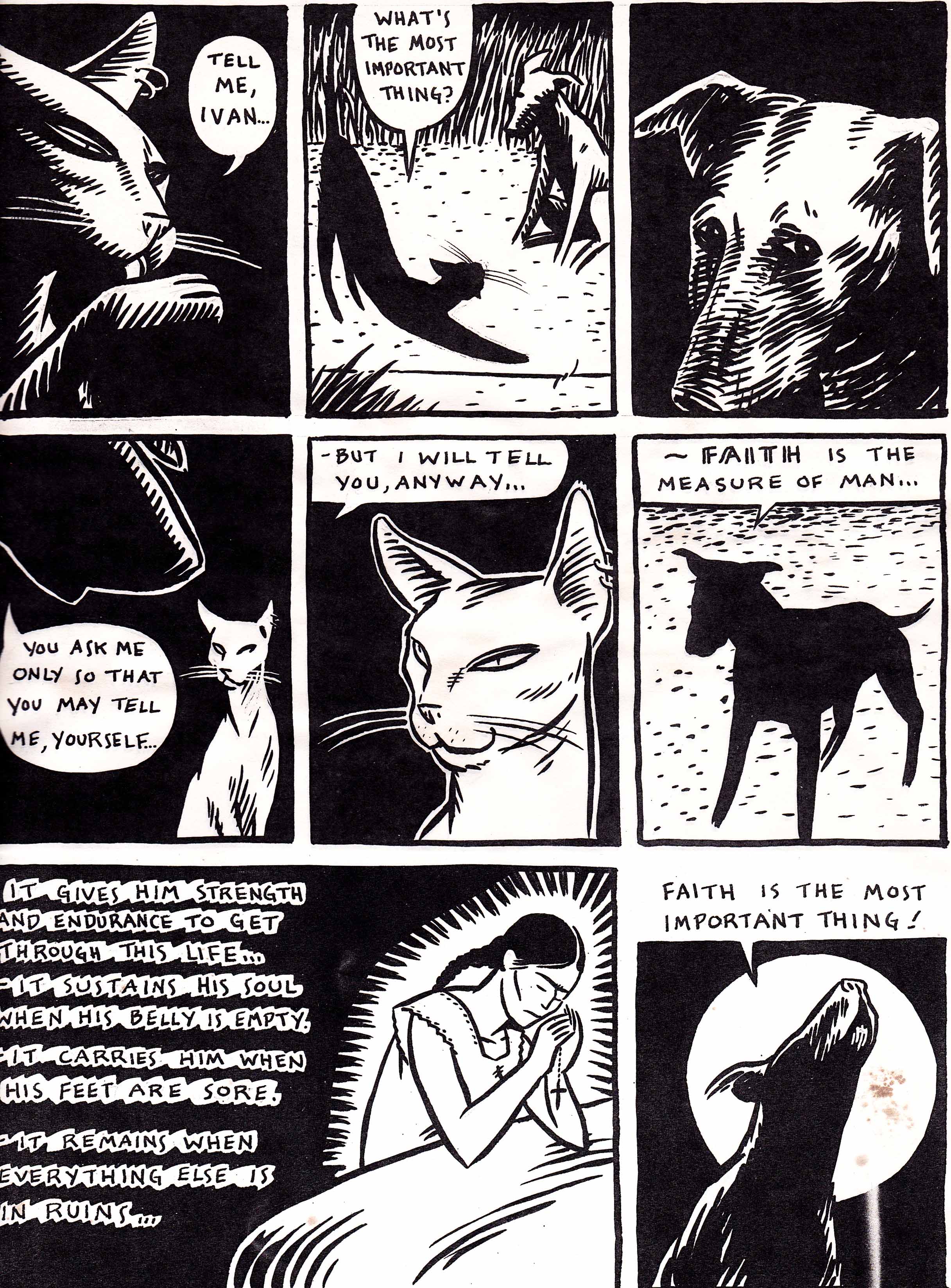

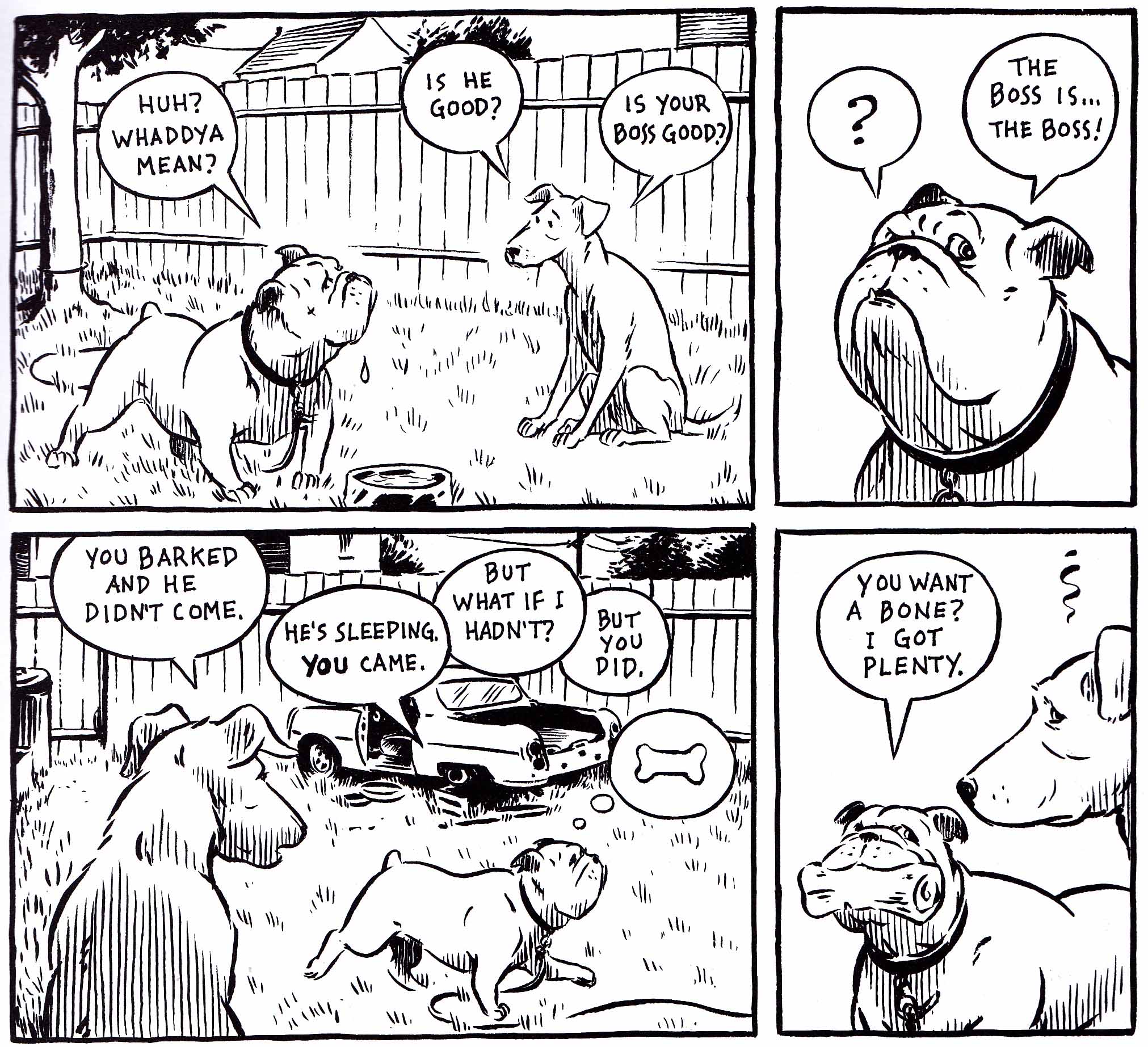

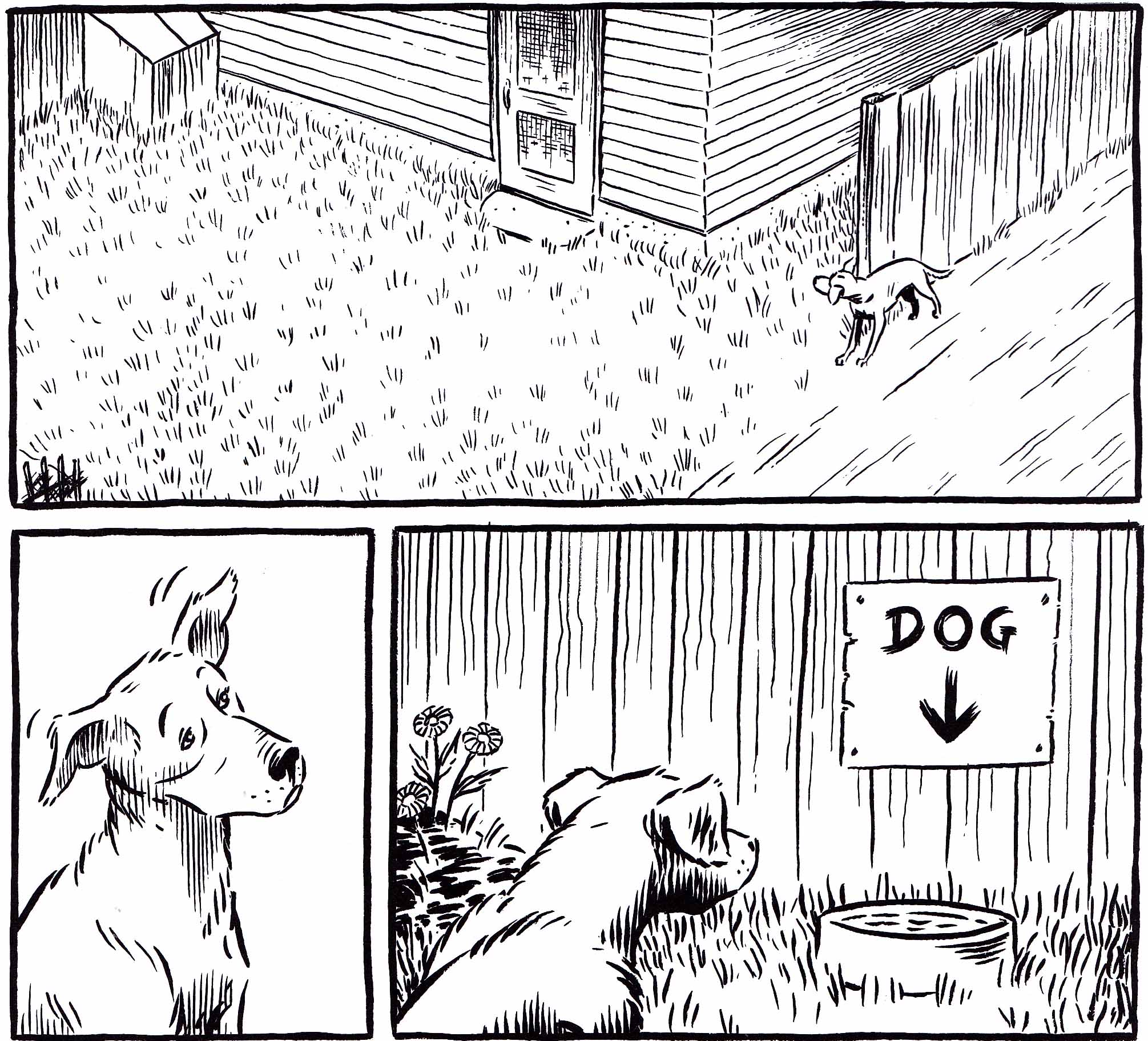

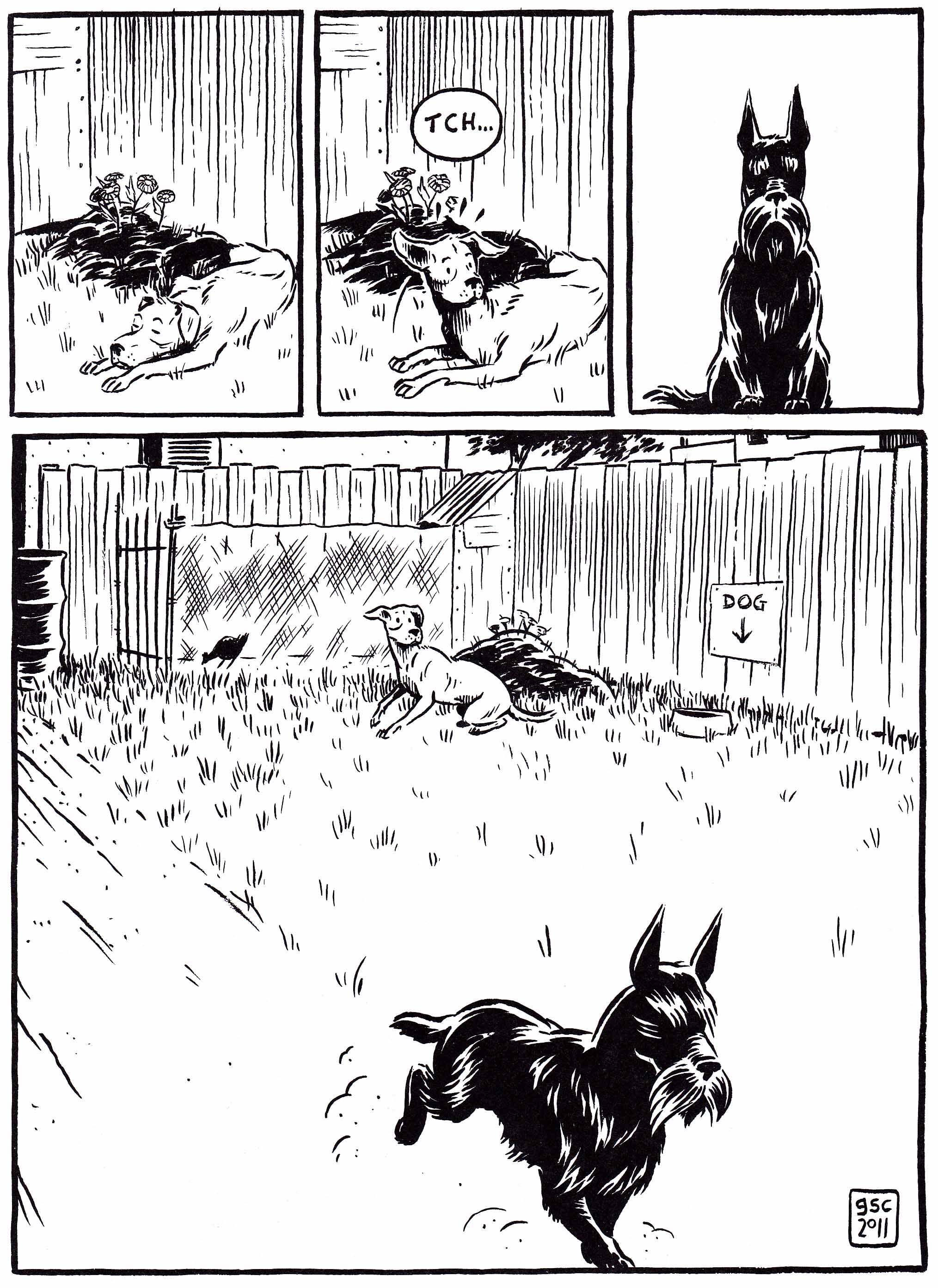

The approach here does seem to hark back to an earlier age of cartooning and pacing—not so much in comic books but in newspaper strips and the woodcuts of Lynd Ward—one which might in fact be compared to an earlier age of film making where structural clarity and a vague kind of verisimilitude was of the essence; a kind of doggy neorealism of the Italian school. Chaffee largely eschews panels which are filled with multifarious meaning and intricate correlations, adopting congenial, unsensational storytelling, evoking time, place and character; the gentle rhythms of a nostalgia associated with the early to mid twentieth century. And as with the meaningful look of the dog, Ivan, in The Most Important Thing (see third image from top), the artist has lost none of his powers of observation, all the requisite emotion of his characters channeled not so much into words but the gentle strokes of his brush.

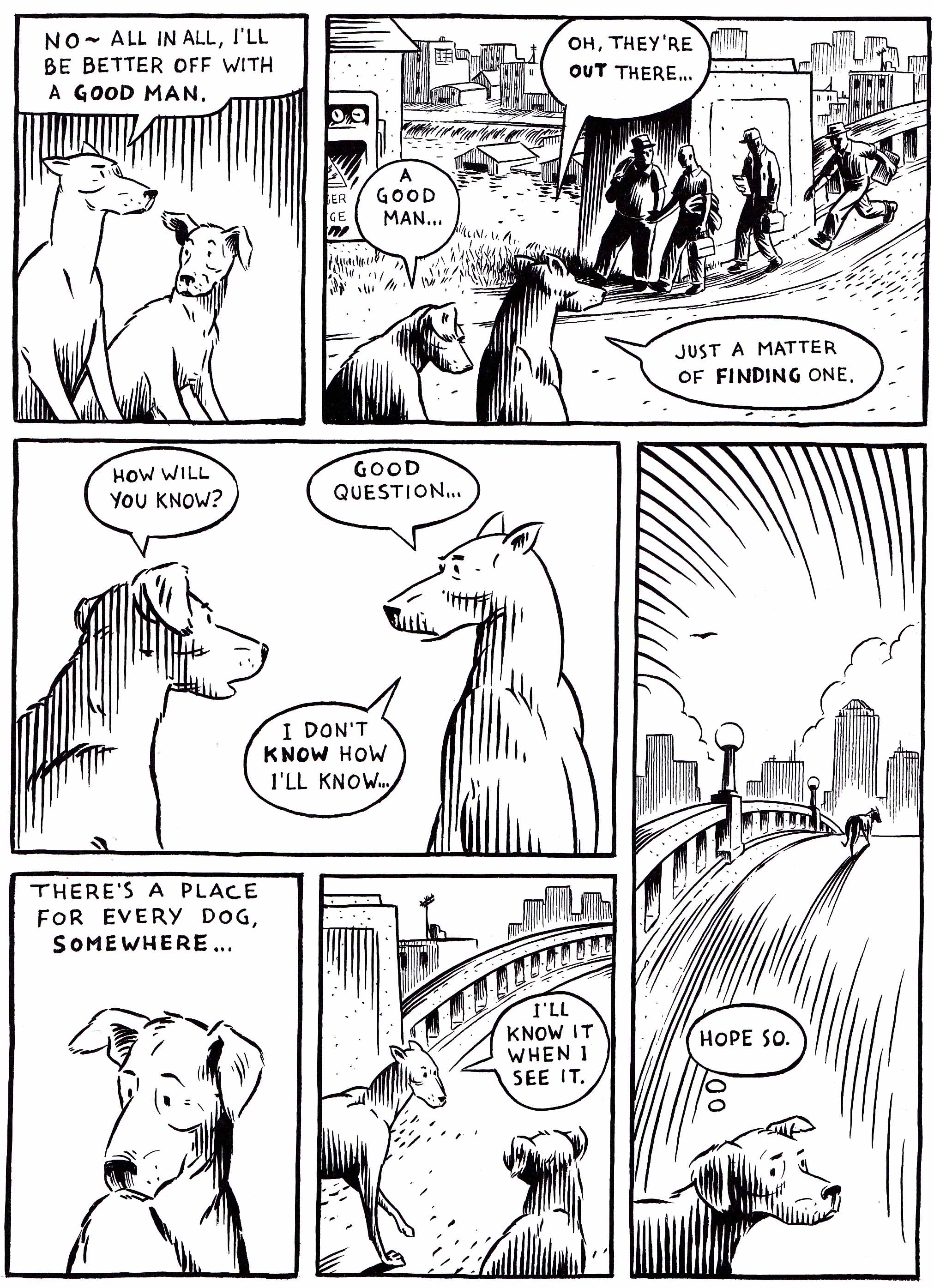

The publicist statement comparing the comic favorably to Animal Farm and Watership Down seems quite unnecessary if not a bit pompous. It is evident that we are to see our foibles in the actions and fates of the dogs which populate Chaffee’s comic. The central questions being tackled here appear to be those of belief, ideology, and faith. A tangential discussion of deist philosophy may not be out of the question as well.

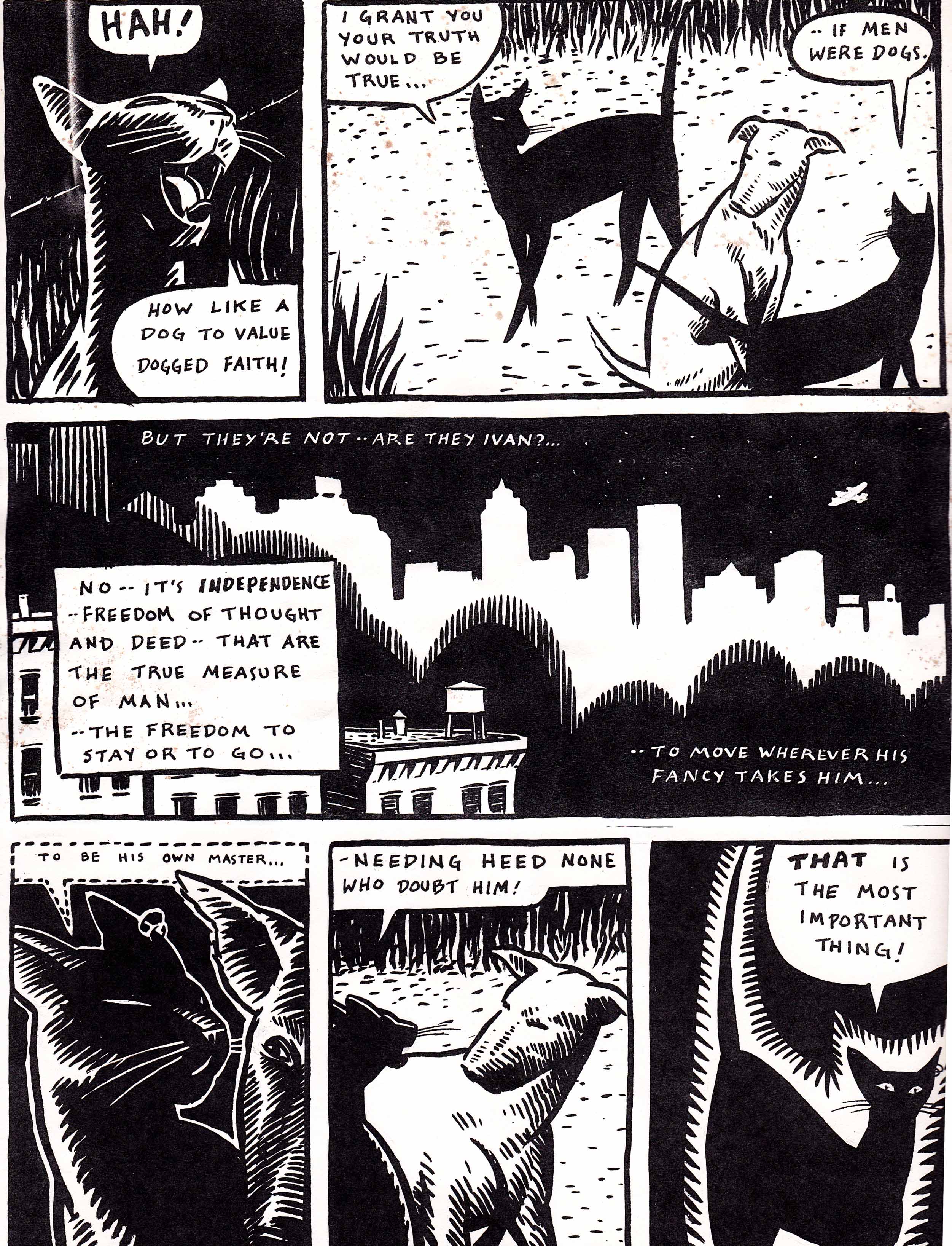

The third page of Chaffee’s debut comic, The Big Wheels, shows a kindly dog licking a man lying in a drunken stupor on the pavement, and the “good dog” of his new book is clearly a reiteration of the dog in the title story of The Most Important Thing, a tale which I remember comparing to Tolstoy’s moralistic fables. Two pages from the latter story should help to elucidate the mysteries presented to us in Chaffee’s latest offering:

In answer to the cat’s question (“What’s the most important thing?”), Ivan answers “faith.” The cat’s answer is “independence–freedom of thought and deed.” A raven, not seen in these two pages, offers a third unspoken answer which appears to be despair and hopelessness. In Chaffee’s new comic, the responses of the cat and dog take center stage.

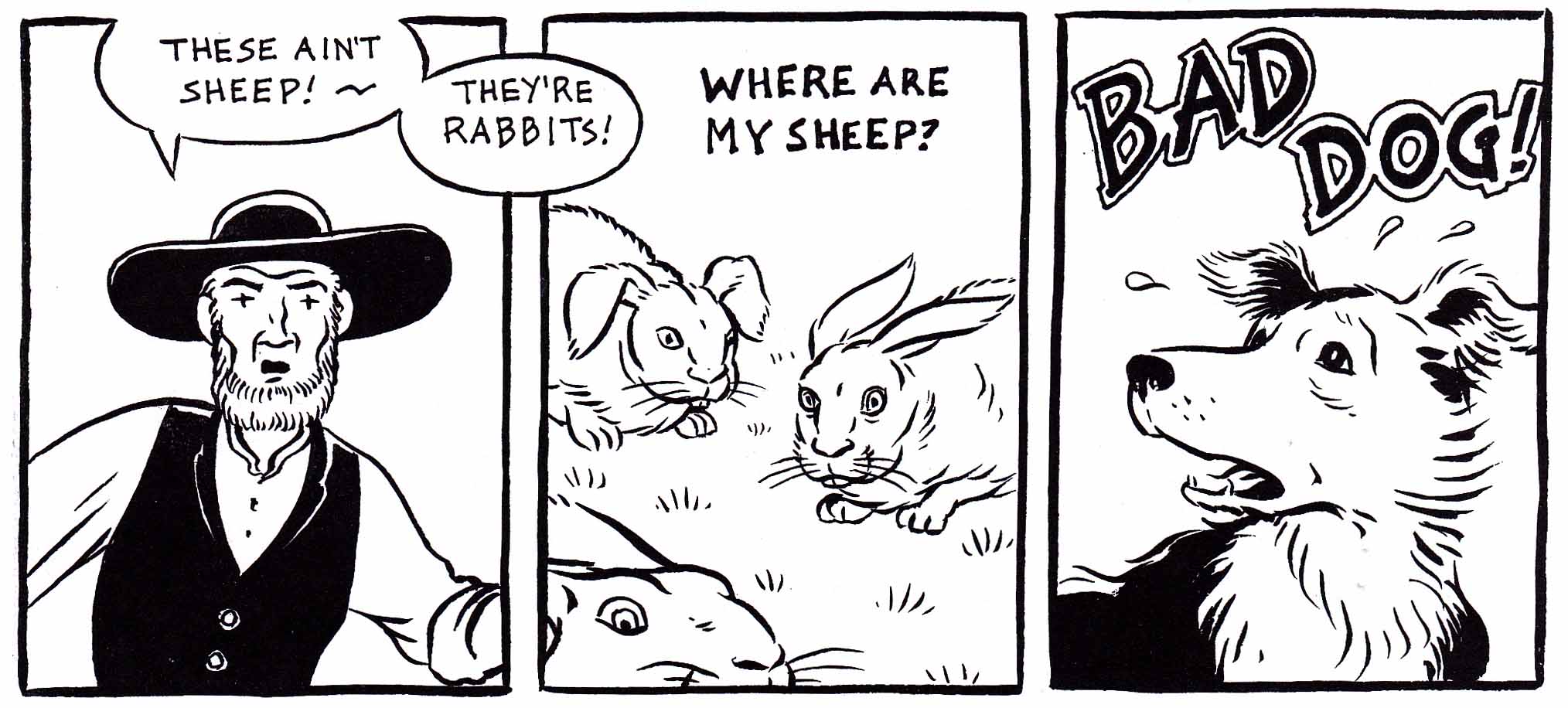

The initial scene in Good Dog shows our protagonist in the midst of a dream where a shepherd instructs him in the act of herding. Ivan seems quite successful at his task but in a cruel twist, all the sheep are transformed into rabbits. He gets a stern scolding from his master and the shepherd’s eyes even turn into little crosses.

In this master-dog relationship, we can see a mirror for our own relationships with our earthly and, if one is so inclined, unearthly masters. There is the question of correct and incorrect action; of duty; and a projection of “original sin” which has little to do with justice or any blessed theodicy than with pure chance and bloody-mindedness.

Once this premise is set up, our dog carries on in his good way leading the vexatious life of a stray, a seemingly hand to mouth existence. The key incidents from this period in his life can be narrowed down to two encounters. The first is with a young black woman called, Babe, who works at a bar called Ray’s 8 Ball (a character culled from the first few pages of Chaffee’s The Big Wheels and a short story in Drawn and Quarterly Vol. 2 #3). It turns out that she needs a watch dog for some chickens in her backyard. His second encounter of note is with a pack of strays led by a Malamute (with wolf ancestry) called, Sasha. The Russian sounding name is probably no accident recalling that hotbed of irreligious brotherhood which is the antithesis of the master-worker dynamic promoted by the bar proprietress.

Sasha’s sole purpose is a kind of heroic striving against merciless life, cruel fate, and unnatural masters—to leave a mark in this world. There is, of course, nothing unusual in this, especially among men of ambition. A familiar example might be Lincoln who was accused in his early political life of being merely a deist and not a proper Christian (he was not a member of any church). We can see in his remarks to his law partner William Herndon that mixture of belief and purely temporal concerns, the urge to be remembered in ways which seem out of keeping with any firm acceptance of a creator:

“…oh how hard it is to die and leave one’s Country no better than if one had never lived for it.”

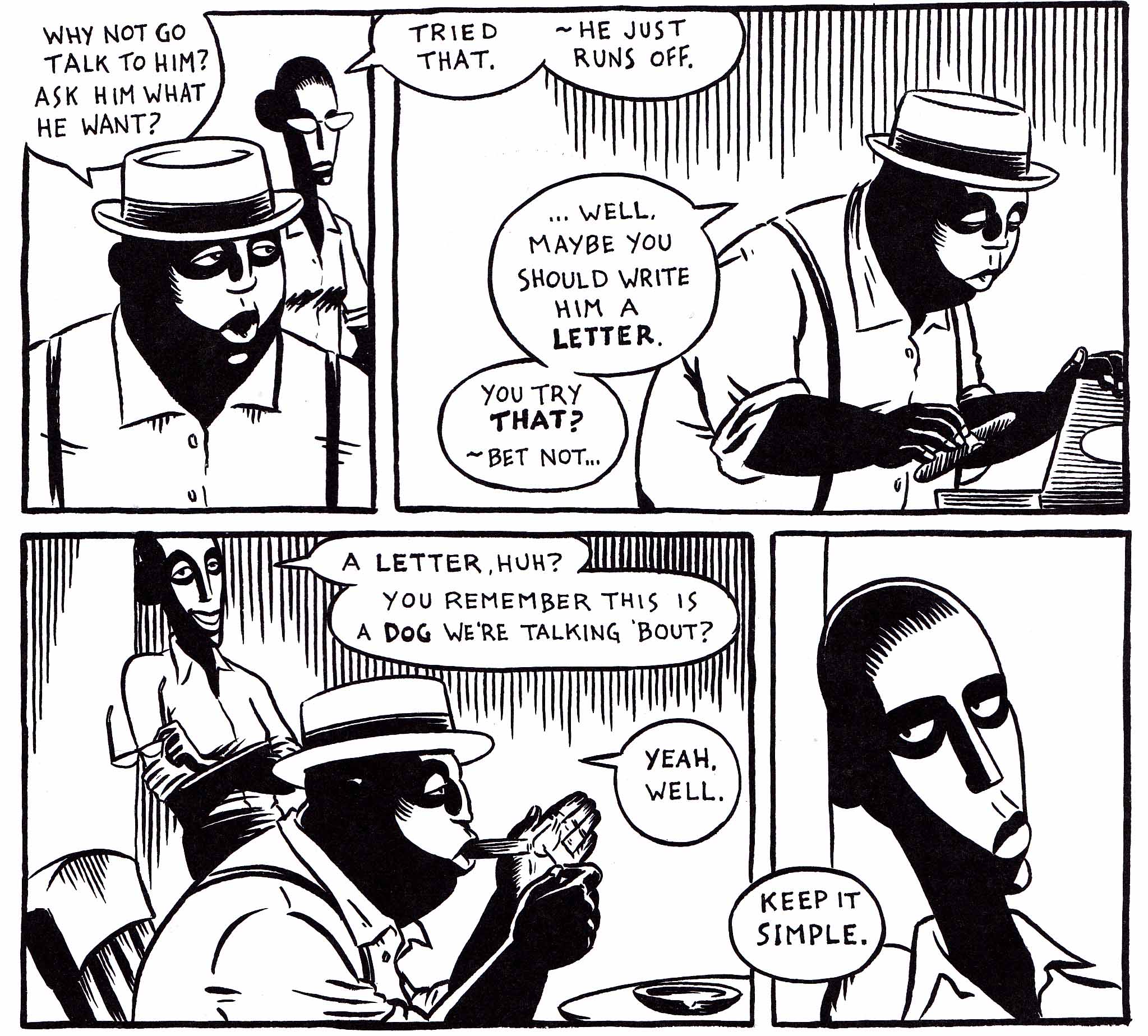

The black woman—not the usual wizened bearded Ancient of Days—tempts Ivan with kindness, water, and food. The impermanence of this arrangement is highlighted earlier in the comic in the story of a dog called, Oliver—leashed to a harsh horse riding instructor who he deserts for the pack upon his death. Another canine friend of Ivan’s, Kirby, is found tied to a tree by his drunken master-god. He is the very image of the foolish, all-trusting believer.

Since this is a comic, one could be forgiven for seeing in that faithful bulldog a metaphor for that greatest of superhero artists. The correlations only go so far though Kirby’s gluttonous, intoxicated, and cruel master may be viewed in some quarters as an accurate portrayal of Marvel.

Chaffee’s presentation doesn’t question the existence of the otherworldly; it is as tangible as the humans which walk around the dogs in his comic. And these creatures are certainly without written creeds or ossified revelation. What matters to them is that single moment of physical comfort and emotional sustenance, ephemeral as it all may be. The death of the pack leader, Sasha, at the hands of the female bar owner leads to the dispersion of the pack and an existential crisis. Some continue their lonesome wanderings but Ivan finds his place at a water bowl left as a token of friendship by Babe—the cryptic epistle written above that bowl as mysterious to him as any divine apocalypse.

Perhaps it is a mark of man’s strange and natural religiosity that he is attracted to it.

At this point, Ivan encounters the Malamute’s right hand dog, a terrier by the name of Sawney. He looks enigmatically at Ivan at rest by his water bowl, presenting us with the singular mystery of the comic. Is that look a sign of disapproval and disgust? Or is it one of longing and satisfaction that Ivan has finally found his place in this world. The answers to these questions, so obvious to many, are in the end quite beyond mere human understanding.