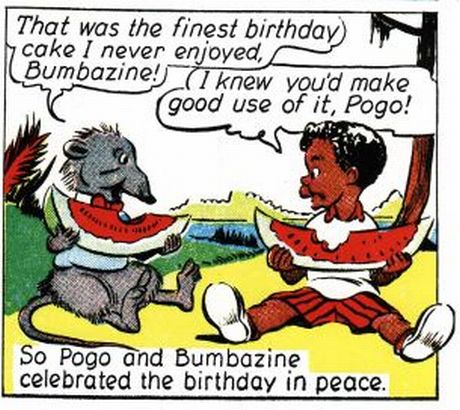

Earlier this week R. Fiore wrote a post at The Comics Journal defending the honor of Walt Kelly from the suggestion (made by Thomas Andrae in the introduction to Walt Kelly’s Pogo The Complete Dell Comics: Volume One) that maybe, possibly, you could see something slightly racist in the fact that he used blackface caricatures.

Fiore’s piece is a graceless performance. He spins and sneers, insisting that this image of a black child with a watermelon is not playing into racist jokes about blacks and watermelons because Kelly isn’t malicious and the black kid is portrayed positively so the watermelon must have ended up in there totally by accident, really, it could just as easily have been grapes. There’s no substantive engagement with, or really even mention of, the fact that Kelly’s cartoon blacks are based in blackface iconography, nor any effort to grapple with what that means.

The really depressing thing is that there’s an interesting article struggling to get out from behind Fiore’s special pleading. Jeet Heer, in the comments to the post, argues that (contra Fiore) Kelly did use blackface iconography but that (as Fiore says) Kelly’s depictions of blacks were in fact better than those of some of his contemporaries. Brian Cremins, who has written in an academic context about Kelly, also suggests in comments that the minstrel tradition was very important to Kelly’s art and humor, and that that’s something to be investigated rather than denied or fled from. I’m not a fan of Kelly’s especially, and haven’t read many of his comics, but it’s clear that there’s a discussion worth having about his relationship to race and racism. It sounds, in fact, like Andrae was engaged in such a discussion.

But Fiore isn’t having it. Kelly cannot have been touched by racism — or, if he was, that only goes to show how utterly awesome and virtuous he really is.

At the outset, we must presume that Walt Kelly was more enlightened than Thomas Andrae, or you, or me. This is because unlike Walt Kelly’s, our enlightenment is socially assisted. Walt Kelly had to come upon his all on his own. Now, any of us might have been one of the enlightened people in those days, and all of us think we would have been one of the enlightened persons in those days, but the odds say otherwise, and in the actual event Kelly was. We simply embrace the conventional wisdom of our time. Kelly swam against the tide.

The suggestion that you or me or Fiore have reached some level of enlightenment which puts us beyond the touch of racism, and therefore beyond moral censure or praise as regards racism, is perhaps the least of the idiocies in this paragraph. The vision of Kelly as great artist, achieving his goal of perfect equality and watermelons without any input from anyone, inventing anti-racism out of whole cloth, without the intervention or help of any actual black people anywhere, is, for its part, familiar in import. Anti-racism here isn’t really a goal in itself; reading Fiore’s piece, it seems fairly clear that Fiore couldn’t possibly care less about racism, or about black people. Anti-racism is just a accoutrement of (white) genius, like a punchy prose style or a pleasing ink line. Fiore admires Kelly’s humanism; if that humanism is compromised, so is the admiration. Ergo, the admiration being fulsome, no racism can exist. QED.

Fiore’s a longtime TCJ hand, and here he manages to embody some of the least enlightening aspects of old school comics fan culture: its hagiography; its crippling insularity (racial and otherwise); its smug distrust of academia; and most of all its defensiveness.

The last couldn’t be more counter-productive. A critical establishment that reacts with panic and dyspepsia to the suggestion that obvious blackface iconography is obvious blackface iconography is not a critical establishment that anyone beyond the most hard-core nostalgists is going to find welcoming. Join Team Comics! We were using watermelons in a totally non-racist way 70 years ago, pat us on the back! If you want to make your art form look clueless, ridiculous, and not a little repulsive, this would be the way to do it. Fiore’s handwaving doesn’t so much distract from the racism of comics’ past as it raises embarrassing and painful questions about the racism of comics’ present.

________

Update: Brian Cremins has a lovely piece about Pogo, race, and nostalgia here.

I can kind of see where Fiore is coming from in the paragraph you quoted, though. Wouldn’t you agree that, generally speaking, it took some courage to call yourself anti-racist 70 years ago, whereas it takes no courage to do that today? I’m 40 years old, and I’ve had similar thoughts about the culture’s shift with regard to gay rights. A lot of young people today advocate for the fairly mainstream position of gay marriage, but if they’d been kids in the 80s, they probably would have adopted the mainstream position of regarding gay people as disgusting freaks.

The deepest academic exploration I’ve seen of this topic is in “We Go Pogo: Walt Kelly, Politics, and American Satire” by Kerry D. Soper. Chapter 4 is titled “Representations of Race, and Borrowings from African American Folk Forms in Kelly’s Work.”

Even though Soper stays firmly on Kelly’s side, he reprints a 1941 Kelly sketch of “Old Man Ribah” with its unmistakable minstrel caricature, and charts the enduring use of blackface, minstrel show, and trickster tale tropes in Pogo. Kelly’s “lazy use…of tired, ethnic caricatures” (a black maid in “The Great Our Gang Circus” screams “Cannaboils is after me!”) is contrasted with Kelly’s advocacy for black hospitals and alignment with the Civil Rights movement.

Your phrase “smug distrust of academia” surprises me. Academia is slowly becoming a strong ally of comics, and it would be foolish to reject their new perspectives and sincere respect.

Hey Jack. I think it depends on who the “you” calling themselves anti-racist 70 years ago would be. Lots of black people were anti-racist 70 years ago. It’s also not clear to me that anti-racism was an especially courageous position for a northern progressive like Kelly; certainly in his milieu I suspect he knew lots of people who were against the KKK. I think a public stand against racism did take some courage, but Fiore is fundamentally misleading when he suggests that Kelly was the only person to take such a stand, or that there were no intellectual or cultural resources to take such a stand back then.

I think there’s also a tendency to downplay the extent to which racism remains a live issue for us now. Tom Andrae wrote about racial issues in what I suspect was a fairly innocuous manner (it’s hard to tell from Fiore’s piece, since he doesn’t really quote much of Andrae’s piece) and then had the major online critical voice of comics criticism take his head off. Obviously, there are people who are willing to defend him too, but clearly it’s still controversial.

It’s certainly true that Kelly’s anti-racism is to be admired. But I think it’s ahistorical to pretend that no one else at the tie was anti-racist, or to say that everyone now is. And it’s certainly confused to look back and present racism as so overwhelming that Kelly’s use of racist imagery didn’t exist.

I think lots of people have changed their minds about gay marriage; it’s an issue on which folks have progressed. But it’s certainly not the case that no one in the 1980s was willing to treat gay people as humans, just as it’s not necessarily true that we’re more enlightened about all gay issues now than ever before in history. In general, I don’t really think the point of these discussions is to make comparisons either to flatter ourselves or to flatter the past. The point is to understand how prejudice works, and (in this conversation) how artists have dealt with it and struggled with it.

Brian, a lot of older comics criticism (including Fiore) comes out of a fan culture which can be very leery of academia. Gary Groth (the longtime editor of the print TCJ) is often dismissive of academics (though he’s worked with and published many academics too.)

I think the distrust of academics is often bound up with a feeling that discussions of race and gender are not worthwhile or are being used to drag down comics greats.

This reminds me of the time Harlan Ellison groped Connie Willis on stage at the Hugo awards in front of God and everyone and his fans proceeded to use his donations to feminist causes as proof he wasn’t the one with the problem.

There was so much stupid in that post.

I agree that there are one or more interesting conversations to be had about the topic, but Fiore has the nuance and understanding of a brick.

I totally heard the part where he chastises Andrae’s use of the term “Little Black Sambo” in the voice of the Comic Book Guy from the Simpsons. As if pointing to the Indian origins of the character somehow erases the way the figure evolved and was used to depict very ugly stereotypes of black children and the subsequent use of the term. He is like one of those people who point to the dictionary to argue that one definition somehow supersedes all others.

That was a really bizarre move.

I was also frustrated that he didn’t actually quote very much from Andrae. I just find it almost impossible to believe that Andrae’s point in the introduction to a volume of Pogo comics was really, “this strip is evil, evil, evil and its creator should be condemned.” But Fiore doesn’t tell us what Andrae was up to, and doesn’t quote a thesis paragraph or anything either.

I’m anxious to hear what Andrae actually had to say in his intro and I hope that he even considers responding to the TCJ column.

I’ve been trying to think through the question of what is really at stake in Fiore’s rant. As I’ve mentioned to Noah elsewhere, I think part of the answer might be found right there in the column’s first paragraph – in the fact that Andrae’s intro precedes the first volume of a newly published collected edition of Pogo. Young kids may not be rushing to buy this, but collectors, scholars, librarians and teachers will spend the money and hopefully keep it in print for a while.

The fact that Andrae’s critical observations (rather than some celebratory bio) will be now tied to the full runs of the comics itself may be especially galling for someone who thinks, in general, that the front matter “irritates” and should be quickly forgotten because “you’re reading the book for comics.” That others have written carefully researched and thoughtful analyses complicating Walt Kelly’s comic art doesn’t matter when they are published by the navel-gazing literaries like us on blogs or in journals that hardly anybody reads (just kidding, everybody reads us!) … but here in a book that is a “collector’s item,” there is a legacy and legitimization at stake. Does the intro’s inclusion in this volume validate the critique in a way that Fiore worries won’t be “merely forgotten”??? Perhaps this is the real danger.

I guess it would be like if future volumes of Uncle Tom’s Cabin were printed with Baldwin’s essay as the preface (well, actually I think the Norton critical edition of UTC may actually have Baldwin’s essay in it). So there you go.

It’s certainly remarkable that one would go through the trouble of writing a reply to a particular criticism without really quoting any of it.

Fiore is quoted more in this article than Andrae was quoted in Fiore’s original piece.

Noah, thank you for continuing the conversation. I don’t know enough about the context, other than what I have read over the past few days (which makes me wary of any assertions of fact now). All I know of Kelly until the other day I would have said, “YES” he has some very nice inked lines and I had a vague notion of the era in which his work on Pogo was done.

It struck me in the midst when reading the Fiore piece, as it has you and others, this strange notion that he accidentally or worse on purpose presented a world where there were two kinds of people; whites and anti-racist whites. Hello, there have been people with dark pigmented skin since the first “people” walked the Earth. Last I checked, that includes the time and place Kelly made these comics.

It can be compelling to look back on old anything, especially Comics, and see the old ways of communicating. We are constantly discoving works which are so horrible contextually we can’t help but treat them as presious artifacts of culture; the horror is mesmerizing, as are the aesthetics and narrative styles. However, we should be conscious of the fact that each of these pieces are acts to repress another’s truth. Erasing history and supplanting (even if total fiction) cultural realities with at best an exploitive, misrepresenting, lazy narrative.

I have no clue what Kelly actually believe, said or acted on when it came to Blacks in America. From the single panel above (not much to go on…especially in comics) at best he is being lazy and letting his subconsciousness draft for him (or there is truly anti-racist panels omitted here). Or worse, he consciously is ignoring how to draw humans and is utilizing not so subtle iconography to put forward his own racist propaganda. It could be in between there, I can’t tell from this place, time and lack of relations with Kelly.

What is missing from the panel is a clear understanding of what the kid SHOULD look like. He needs better reference and then filter it through the Walt Kelly style. Not take a racist cliche and barely make it his own.

It is easy for us now to cradle nestalgia and claim enlightenment as a reason to hold this sort of work in high esteem. It is hard to look at those who come before and inform our own work (or culture and childhood) with critical eyes. Especially when we often lack a full understanding of the context of intent and the reality the artist/writer was experience at the time. Somtimes we have these answers in part, but it is never perfect and easily misunderstood by subjective perspective. We reationalize that the Cartoonist can’t answer for their sins. What we mean really is we can’t defend our own pleasure in consuming it’s content.

Much of my nostalgia was formed in the crucible of a mostly Black neighborhood. I can tell you, this helped me respect and understand intellectually some realities for some individuals in my neighborhood. However, we are all individuals and I have no way of feeling exactly what my neighbors felt most of the time. Nor did they fully understand mine. Heck, I don’t fully get mine.

So, I would think, Noah, you are right, these sort of dialogues and works expose not just racism in the past, but in the present. Also, it exposes the complexity of our individual perspectives, the lack of clarity available in history and the importance of balancing our love for something or someone and our search for truth. These paths are not always in harmony, but we need both to understand our past, to inform our potential in the future and get real about our present, or at least care about any of it.

We’re going to have a post later in the week that will go more into Kelly’s politics, as well as nostalgia…so stay tuned, as they say!

Hi Noah,

I agree with much of what you wrote here but want to clarify (or add on) to one point. I think some of the criticism against Fiore has been misdirected because it accused him of trying to deflect Kelly’s racism by contextualization. To me, a more accurate accusation would be that Fiore’s account of Kelly suffers from de-contextualization or inadequate contextualization. I’ve already gone over this elsewhere, but issues of racial representation were fiercely debated in the 1940s, especially in the Popular Front milieu that Kelly operated in (both at Disney and later at the New York Star he hung out with the Popular Front crowd). I think a discussion of that context, and also the larger issue of how New Deal liberals dealt with race, would take us closer to understanding what Kelly was trying to do in those strips (and if he failed, as arguable he did, we can at least have a better sense of the goal he fell short of or the limits of the politics he embraced). But, yes, the idea that Kelly came to his ideas on race by himself isn’t a good way to think about this.

More broadly, I think it’s a mistake to equate contextualization with apologia. Contextualization actually sharpens criticism and can often make judgement more damning, not less. (I think a fuller awareness of anti-Semitic tropes and their history has made me more, not less, critical of Oliver Twist and the Merchant of Venice. Eisner’s Ebony White is another case — if you have a sense of the context of the early 1940s, Ebony White looks even worse because you are aware of how disputed that image was at the time).

I agree with that. I think part of the confusion is that the way Fiore uses context is very odd…which I guess could be another way of saying it doesn’t seem very attentive.

I would like to point out that I quote about as much of Thomas Andrae in my column as James Baldwin quotes of Uncle Tom’s Cabin in “Everybody’s Protest Novel.” Which is longer.

Baldwin could assume that folks were reasonably familiar with Uncle Tom’s Cabin, I think. He was certainly writing for people who were familiar with the book.

I mean, I literally don’t know what Andrae said from your review, Robert. I doubt he was just saying, “Walt Kelly is racist, don’t read this book.” But that’s pretty much all that comes through from your paraphrase of him.

I did a brief essay on this kind of thing a while back, specifically on the actual racist content of Will Eisner’s work:

http://tilthelasthemlockdies.blogspot.com/2008/04/false-hero-worship.html

Thanks! I think I’d heard that story, but hadn’t read the original post.