I have been thinking about access in comics studies lately, about the way the availability of resources can be used to steer critical interests in the field. Publishing houses and archivists, collectors and copyright holders, even cultural guardians – there are a lot of people and institutions involved in making decisions about which titles to seek out, preserve, and keep in print. Of course, anyone who works among the ephemera of popular culture faces similar challenges, but my question focuses on the implications for comics scholarship: How does access to materials shape the choices you make about the comics you study, teach, or review?

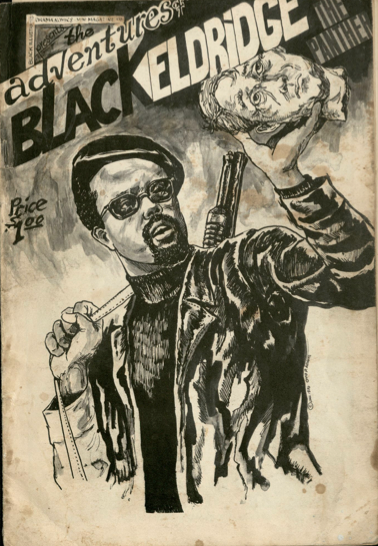

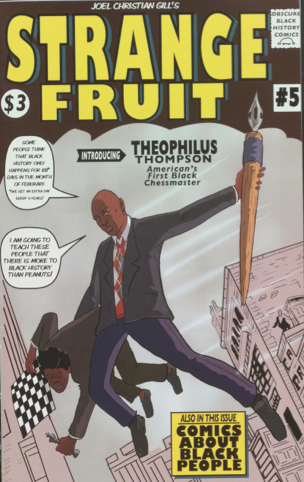

Last week, I visited the comic book archives at the Library of Congress in DC and at Virginia Commonwealth University’s James Branch Cabell Library in Richmond. Although I arrived with a list of rare comics and fanzines that I wanted to read, the best part of spending time in archives was getting the chance to talk with the reference librarians who maintain the collections and know where to look for hidden gems. Thanks to Cindy Jackson at VCU, I got to turn the pages of The Adventures of Black Eldridge: The Panther, a newly-acquired underground comic produced by Ovid P. Adams in 1970. Megan Halsband at the Library of Congress introduced me to Joel Christian Gill’s recent series of Strange Fruit Comics that uses satire and comics culture to dramatize obscure black historical figures (along with great bonus features like “Lil’ Nino Brown in Slumland”).

You may have to travel to Richmond to see Black Eldridge wield his machete against the villains of white supremacy, but Gill blogs about his work online and his Strange Fruit Comics are being collected in a new edition out this June. And it’s a good thing too, because quite a few of the titles I regularly teach in my class on race and comics are now sadly out of print and I don’t know how long I can keep asking students to hunt down used copies.

Questions of access must also take into account the way comics as a form continues to be disparaged ideologically by those in positions of power. Complaints that the College of Charleston forced last year’s incoming students to endure lesbian “pornography” in Alison Bechdel’s graphic novel, Fun Home, also prompted South Carolina State Representative Tommy Stringer to tweet: “Is the instructional ability of CofC teachers so low that they have to use comic books to teach freshman?” The material consequences of this kind of thinking are extremely serious; the state ultimately voted to slash the first-year reading program’s dollars from the college’s budget.

One wonders if Rep. Stringer would level the same accusations of teacher incompetency if the College of Charleston had selected March: Book One for their freshmen reading selection, as Michigan State and Marquette University are doing this fall. U.S. Congressman John Lewis has been signing copies of his graphic novel memoir to standing-room only crowds across the country. In interviews, Lewis along with his co-writer Andrew Aydin and artist Nate Powell have often praised the ability of comics to inspire social change and reviews celebrate the novel’s success as a teaching tool. Furthermore, the 1958 comic book, Martin Luther King and The Montgomery Story, is available for purchase again due, in part, to a reference in Lewis’s graphic novel and the publicity surrounding distribution of the comic book’s translated Arabic edition during the Arab Spring in 2011. I suspect that high schools and colleges will keep these comics in print for a long time.

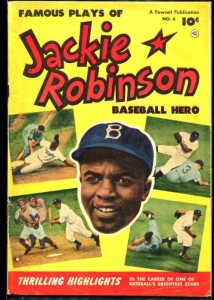

The research that I’m doing now on EC Comics greatly benefits from the initiatives of fans that have worked hard to keep reprints in circulation. The same can’t be said, though, for comics like Fawcett’s Jackie Robinson series, also from the 1950s. Last week, I had the chance to read three issues (three!) from the series, along with one about Joe Louis and Willie Mays, all incredibly fragile and rare. I’m eager to write about these comics, to try to make some kind of meaningful connections with other titles produced during this period. (Who knew that Robinson apprehended cat burglars in his spare time?) But now I’m realizing how important it is that we also work with publishers to make these comics more readily available. If readers can’t get better access to titles like Jackie Robinson or The Adventures of Black Eldridge, how can they become a part of larger critical conversations in comics studies?

They can’t.

I mentioned this in the romance piece I had on Salon this week; when genre is low status, there aren’t mechanisms for keeping work in print, or bringing it back into print. One of the ways that cultural validation has a real effect on what’s available.

An important topic, but perhaps so basic we tend to overlook it. I’d add to this by noting a curious middle-ground: comics that have been reprinted, but in expensive editions, many of which go out of print quickly. So the comics are available to contemporary readers, but practically inaccessible for those of us who teach comics. Simply put, I’m not going to assign a rather expensive (sometimes very expensive) book to a class, and, again, these often go out of print after an initial small run. I’d like to teach EC Comics, which as Qiana notes, have been more consistently available than many others, but currently that would mean relying on either the reprints from (now) Dark Horse or Fantagraphics, both pretty expensive for students who have no interest in acquiring these volumes as collectors. (I’m not getting into the issue of making copies, scans, etc.) The situation with libraries has gotten better — many of our libraries will now acquire comics when they wouldn’t before (but does any academic library have a standing order of DC Archives or Marvel Masterworks editions?) — but that’s a limited solution too, as anyone who has tried to have a class of students all rely on a single library copy of a book knows. In addition to the difficulty of teaching African American comics that Qiana focuses on, I’ll add another, surprising one: romance comics. One of the most popular of all comics genres for decades barely survives in contemporary reprints, and I”m convinced that its eclipse in recent comics scholarship stems in large part from this invisibility, not just the domination of the superhero genre and male fans (though those are of course a factor too). Right now a vast amount of Jack Kirby material is available for readers and scholars — except for his romance work (a small fraction of which is included in two recent — and again, fairly expensive — Fantagraphics collections.)

That Ovid P. Adams comic looks incredible. I’m looking forward to reading more about the treasures you uncovered on this research trip, Qiana!

I’ve run into similar challenges in my Captain Marvel research. While digital scans of the original comics are easy to find online, I’ve had more difficulty tracking down the fanzines and other small-press publications that featured work by folks like Beck and Binder. Like you, I’ve been lucky to work with archivists like Randy Scott at MSU and with the special collections at Texas A&M, but I’ve found that even those amazing places, and others like the Billy Ireland at OSU, are still in need of additional archival material.

One of the solutions to this challenge, I think, is that, as writers, scholars, fans, and collectors, we make sure that, when the time comes, we donate these rare materials to the archives so that future artists, scholars, and fans have access to materials that would otherwise be ignored or lost.

But your post raises other important questions. What gatekeepers decide upon the works that rest in those archives? As writers and teachers this is where I think we play an important role in introducing obscure and neglected works to other writers and to students. Part of this process of sharing is, I think, an essential part of the community-building that artists like Edie Fake and Samuel Delany talk about in their work. As we build these communities and tell these stories, we not only bring life to the past, but we also share the excitement of doing archival work. At the same time, I think it’s vital that we write about and teach the work of contemporary artists whose work might be neglected, so that those artists can find material support for their work and continue producing art that teaches and inspires us.

And I can’t wait to read more about these Jackie Robinson comics…

A similar problem is that many of the world’s greatest comics are not available in English and probably never will be. Just as a random sampling, authors like Fred, Oesterheld, Gotlib, Carlos Gimenez and Jean-Christophe Menu are absolutely central to the way people in other countries think about comics, and yet there is no financial incentive for anyone to translate their work. And because most comics readers in English-speaking countries can’t read their work, we get a skewed historical perspective on comics. This situation is gradually changing — there are now many more companies that are willing to translate the best European comics, for example — but we don’t have access to the comics that inspired people like Trondheim and Sfar.

Something similar that’s been annoying me recently is that so many of the classic British humor comics (e.g. the works of Leo Baxendale, Ken Reid and Dudley D. Watkins) are completely out of print and no one seems to care about reprinting them, even in the UK. Whereas British adventure comics like Dan Dare and Heros the Spartan are currently in print.

Our perception of comics history is shaped by sometimes arbitrary decisions about what does or doesn’t get reprinted and translated.

Yes, translation is a persistent problem too — actually I’d say the number of comics translated into English has reduced lately from an earlier high point (that was never that high), when companies like NBM and Catalan were around. This is where the loss of Kim Thompson is likely to be felt given his valiant efforts at getting European material into English: I hope the FB Kickstarter campaign keeps his mission alive. Actually the situation I mentioned earlier applies to British adventure comics like Dan Dare too: these were reprinted in fairly expensive, nice editions by Titan: a few of those are now out of print, and go for outrageous prices now. Comics are often caught between the desires of readers and the desires of collectors.

Also, film studies has historically confronted the same problem and still does, but compared to comics scholars, film scholars are much more aware that inaccessibility of old films is a significant problem.

You run into these problems even with relatively high profile work. There’s no good, affordable collection of the early Wonder Woman comics, for example — and when those comics are reprinted it’s often with crappy recoloring.

It seems to me that situations like this outline one of the most important ways academics can actually contribute to a field and to larger culture. As a 19th century Brit Lit scholar, my ability to expose students to female poets like Letitia Elizabeth Landon and Felicia Hemans is only possible because a previous generation of critics worked to revive discussion of these authors . Even a major figure like William Blake would not be part of literary canon today if it hadn’t been for the resurgence of interest he experienced at the outset of the 20th century.

For a more appropriate example of how this can be achieved for comics, its worth considering the efforts of Rachel Richey and Hope Nicholson in reviving Nelvana of the Northern Lights at http://nelvanacomics.com/

They’ve taken a combination of approaches (a Kickstarter for publishing new editions, creating a documentary about Canadian superheroes, setting up tables at cons) to raise awareness of the character and make her work accessible.

As Keith notes, there are significant models here in literary studies: feminist and African American studies scholars were confronting the fact that so many key works and figures were out of print, and this led to a lot of important recovery work. At one time nothing by Zora Neale Hurston was in print, and she’s now a canonical figure, including in the Library of America and perpetually in print since those efforts. Will comics scholars ever have that sort of impact?

High-quality online facsimiles (scans) of public domain material would help greatly; of course these are often available on the sly, but it would be great if we could get some funded scholarly projects to really do this work up right, with historical context, etc.

Commercial incentives for reprinting now-obscure comics in hard copy must be very low, so much so that even scholarly publishers would be hard pressed to jump in.

I’d love to see some of the private or ad hoc efforts to scan old, old comics receive proper funding and exposure. Public domain material from the so-called Golden Age of US comic books can be found on the QT via online scans; in fact the bulk of Golden Age comic books is probably more readily available now, through unofficial digital facsimile, than at any other time since first publication.

Really appreciate these comments, everyone. Keith, thanks for the link to Nelvana of the Northern Lights and the examples about the way criticism can actually help make rare materials more accessible. Makes me think that Henry Louis Gates, Jr. was on to something when he turned away from literary criticism and moved into editing and promoting rare, newly-discovered African American novels and slave narratives. That’s not a role I ever imagined myself playing, but I guess if we want to keep this stuff around…

Since film studies was mentioned, I’m really curious about how film scholars approach this issue, given the care and expense required to find/preserve films and having the right technology to view them. Has the institutionalization of film studies helped to maintain a wider variety, availability of materials, or does it still feel as arbitrary as the way comics are handled?

Charles, I’m glad you brought up online scans. I wasn’t sure if folks would want to talk about using them, public domain or…otherwise. I’ve come to rely quite a bit on unofficial digital facsimile and this is obviously not my preference. Proper funding and exposure for these older, rare comics would be terrific.

The Hurston example is also a really good one, Corey.

And since someone mentioned film studies, I should mention this issue is also frequently discussed in game studies, where the obsolescence of technology frequently renders past games unavailable for study (not to mention the collapse of communities that populated online game communities). That’s really a whole other kettle of fish, but still interesting.

With material from the 1950s and before, one might want to check on its copyright status. The copyrights may not have been renewed when the initial term ended, and in some instances they may never have been filed in the first place. If that’s the case, I believe you’re looking at public domain material, and there’s no reason not to scan for posting online..

Not sure I can adequately answer the film studies analogy in a short space! I would say that film studies absolutely drove some preservation efforts and made some films accessible, but there are always rights issues and financial issues intertwined. There’s also a coordinated, international film archive association — rather unlike the archives of comics, which are not coordinated in the same institutional way, and are not (so far as I know) involved in restoration work that sees rare material released to the public. But there is indeed a haphazard quality — to put it bluntly, there’s not much work on films that don’t exist! (However, there is a body of film studies that does work on film culture despite lost films — almost nothing of early Indian cinema survives, but since posters, reviews, still photos, etc. do there’s in fact lively work on this period despite the absence of actual films.) The film-comics analogy seems to me to offer as many differences as similarities. (At a certain point film studios saw reasons to preserve copies of their own productions: I take it that this was true of comics publishers with file copies — what gets tricky is when a film company or a publisher goes out of business, and those collections are destroyed or dispersed.)

I’d also argue, to return to one of Corey’s earlier points, that we’ve already seen the sort of impact scholarship about comics can have in introducing texts to a wider audience. I think the popularity of Maus in college courses and in some secondary classrooms might be traced, at least in part, to the work of pioneering scholars like Joseph Witek and Marianne Hirsch, who began writing about Spiegelman at a time when comics, despite a body of existing scholarship documented, for example, in Jeet Heer and Kent Worcester’s collection Arguing Comics, had yet to be taken seriously in the academy, at least here in the US.

So while scholars like Witek and Hirsch, for example, didn’t save Maus from the kind of obscurity that Hurston’s novels suffered, of course, they gave a kind of permission to other scholars to look more closely at comics, just as Samuel Delany did, for example, in his groundbreaking essay on Scott McCloud and the paraliterary. I mention the ascendancy of Maus as a canonical text—not just for comics, but for American literature more generally—as an example of the very real impact scholarship can have not only on how we read texts but also on what texts are being read.

For all that’s not available I tend to agree with the common claim that we are now in a golden age of reprints, of comic strips and comic books: who can keep up with all of it? But most of that activity seems directed towards collectors, not even readers (the cheap Marvel Essentials and DC Showcase volumes might be the exception), and certainly not classroom use. That’s what justifies large, fancy, nicely designed hardbacks, which tend to range from $50 to over $100 each. The rationale for Marvel’s Omnibus editions seems to only be to satisfy collectors who want massive collections of key comics: they are literally hard to read, and go out of print quirky and then command even higher prices that their initial (usually $100 or more) prices. I wonder if any comics publisher (unlike, say, Pantheon, which does market some of its graphic novels to educators) ever thinks of their titles as textbooks?

Translation is the ultimate barrier. Some of the most compelling comics ever made might never make it into English, and thus will never be considered part of the English-language “comics canon.”

I’ve written about that a few times myself… it’s an interesting topic to me, because people really do talk about the comics canon as if it’s this settled thing, but there are so many accidents and random happenings that have determined what is and isn’t available…

My research has been severely distorted by Marvel and DC maintaining control over the rights to comics published in the 1950s (comics that not even their creators thought worth saving at the time.) This means that I pay disproportionate attention to the work of small, dead publishers, posted at http://digitalcomicmuseum.com/ or http://comicbookplus.com (which I happen to like better.) Similarly, the Alexander Street Underground and Independent Comics, Comix, and Graphic Novels Series, which my University subscribes to, consists largely of works that have usually been lost in the shadows of the canonical underground comix that are missing from that database. (I don’t mind. I already own the canonical stuff, and Alexander Street sends me royalties.)

The work of comics scholars to elevate the importance of particular works may make these things more available at a price, but less likely to slip into the public domain. Speaking of our underappreciated public domain, I have been receiving multiple alerts this week about the current Trans Pacific Partnership (TPP)negotiations, which include the idea of extending monopoly rights over corporate intellectual property to a term of 120 years.

One significant factor is that a significant portion of the comics industry (though by no means all of it) is of interest to geeks. This has significant consequences for preservation – the truth is that if you want a comic by Marvel or DC, no matter how obscure or out of print it is, you can find it and have it in a readable format within half an hour. For major writers like Alan Moore there are barely twenty pages from his entire career that can’t be tracked down.

This typically requires piracy, of course, which is its own barrier to access, but the point remains: illicit preservation changes the nature of what can and can’t be done in scholarship.

Just to repeat a point in relation to Phil’s comment — you can get almost all Marvel or DC material except: 180 issues of DC’s GIRL’S LOVE STORIES, 160 issues of DC’s GIRL’S ROMANCES, over 200 issues of Marvel’s MILLIE THE MODEL, etc. There’s a major gender component to what is and is not available …

Corey, I suppose you already know this, but if not, it might be of interest: Jacque Nodell’s been blogging about “romance comic books and the creative teams that published them throughout the 1960s and 1970s” at Sequential Crush.

One of the major torrent sites has a 50+ part series of torrents that aims to collect absolutely everything DC has ever done. Looking at their file lists, it looks like one can get scans of all but 44 Girls’ Romances and 43 Girl’s Love Stories on short notice – and that’s without using esoteric private trackers. There’s not a Marvel equivalent, so indeed, Millie the Model is currently inaccessible.

Still a hole compared to the rest, but one that suggests that there’s a fair number of geeks interested in preservation and comics history in the general case as opposed to male-targeted superheroes.

Certainly that’s been my experience working with British comics, where I have on occasion needed some extremely obscure and marginal single issue scans and have thus made the acquaintance of a few of the scanners in that area, who, while male geeks, are interested in the form and history and will scan just about anything if it’s British and a comic.

Who gives a fuck how availability affects comics “studies.” It affects the comics MEDIUM and the artists who work within it far more deleteriously.

“Corey Creekmur says: …you can get almost all Marvel or DC material except: 180 issues of DC’s GIRL’S LOVE STORIES, 160 issues of DC’s GIRL’S ROMANCES, over 200 issues of Marvel’s MILLIE THE MODEL, etc. There’s a major gender component to what is and is not available…”

Yes, you’re right. If men hadn’t written and drawn those comics some fifty years ago, they never would have existed.

Kris, comics studies is as valid a form of expression as the comics medium.

And men who work in feminized mediums can get fall our from misogyny. Which is one reason that pointing out misogyny is not anti men.

Pingback: Did I post this already? | joelchristiangill