There is no rule stating that fantasy literature must involve a pre-industrial setting, but Tolkien’s grip remains strong and the maps included at the beginning of epic fantasy novels illustrate a strong attachment to land rather than economic “development” (or degradation, as per Tolkien’s philosophy on modernity.) Pre-industrialization, by its very definition, eschews mass production and growth. Even in urban fantasy, the modes of production that sustain the magical world don’t usually involve factory processes. There are notable exceptions, of course, like Stephen King’s The Dark Tower series, but I think this description is a fair representation of the genre.

The role of “stuff” in fantasy fiction remains vitally important to fantastical stories and potentially serves to discipline fantasy readers into valuing certain cultural artifacts over others. Wikipedia has a page dedicated to a sizable—and incomplete— list of fictional swords with names. Certain artifacts are imbued with symbolic qualities (eg. King Arthur’s Excalibur and Holy Grail) and some magic systems are reliant upon material things (eg. wands in Harry Potter.) Though economic systems within fantasy literature are usually underdeveloped or neglected by authors, artifacts remain fetishized, used both as a way of adding authenticity to the secondary world (the presence of swords signals to readers that they are situated within a particular genre and provides a pathway for authors to play with certain tropes), and developing the protagonist’s identity. But from where does this economic model originate and how, if at all, does this conceptualization of stuff impact present-day nerd consumerism? Because while the role of economic exchange is left ambiguous in much fantasy literature, the centrality of stuff like wands, crystal balls, amulets, and named swords are not.

J R. R. Tolkien creeps into most discussions of fantasy literature, even when intentions are bent on his exclusion. China Mieville, both highly critical and highly thankful to the man, once called Tolkien “the big Oedipal Daddy” of fantasy literature, a label with which I’m forced to concur. Tolkien was heavily influenced by his academic work as a scholar of Anglo-Saxon literature, a research interest which inevitably shapes this discussion. He began writing The Hobbit shortly after translating the epic poem Beowulf. The dragon in The Hobbit is thought to be directly influenced by the epic poem. Tolkien’s work emulates Beowulf’s vagueness surrounding the production of goods, features similar rural mileus, and focuses more on treasure than merchandise. In his book Honour, Exchange, and Violence in Beowulf, Peter Baker writes:

[T]he world of Beowulf gets along entirely without coinage. The poem mentions land as a reward for valorous deeds, but land seems to lack all practical value: if noble Danes and Greats collect rents in money, food or service, the poet considers the fact too trivial to notice…Indeed, the only category of wealth that interests the poet and his characters is treasure.

The acquisition of treasure was done primarily through looting, and Baker writes that violence in Beowulf was not seen as a sign of social disintegration but as an ‘essential element in the heroic system of exchange (sometimes called the Economy of Honour.)’ In general, the accumulation of goods in fantasy literature is linked with the successful completion of good deeds. Part of the hero’s journey may involve a quest to recover certain items, yet the acquisition of stuff in fantasy literature is not about consumerism but a reflection of the protagonist’s righteousness or destitution. In Beowulf, for example, treasure is used to secure loyalty and ensure the continuation of a just society. Further examples include the destruction of the One Ring, the destruction of the Seven Horcruxes in order to defeat Voldemort and the search for the Deathly Hallows, and The Sword in the Stone– an object which arbitrates rightful inheritance to the throne.

Though not all fantasy settings are rural—and some fantasy authors focus on urban settings as a reaction to Tolkien’s idealization of pre-industrial life. Michael Moorcock, in particular, argued that Tolkien’s fascination with pre-industrialization was nostalgic and “infantile.”

Since the beginnings of the Industrial Revolution, at least, people have been yearning for an ideal rural world they believe to have vanished – yearning for a mythical state of innocence (as Morris did) as heartily as the Israelites yearned for the Garden of Eden. This refusal to face or derive any pleasure from the realities of urban industrial life, this longing to possess, again, the infant’s eye view of the countryside, is a fundamental theme in popular English literature.

Even in fantasy novels that feature urban environments, magical items are not produced through the methods of mass production. There aren’t too many wand-making factories. When large-scale manufacturing operations are displayed, they are usually situated as a site of oppression. Tolkien described the industrial period as “the robotic age,” despite early industrialization’s reliance on cheap sources of labour (women and children). The rejection of the methods of mass production is not unconscious on Tolkien’s part—Sarumon’s destruction of Fangorn Forest to pursue his own mining operation is portrayed as unabashedly evil. More recently, Brandon Sanderson’s excellent Mistborn trilogy features a covert mining operation controlled by an elite class that would like to restrict the use of magic (Sanderson’s magic system is fueled by minerals) and which is the site of class oppression and slavery.

I find the absence of economic preoccupation, which centers contemporary life but is pushed to the periphery in fantasy literature, fascinating. There’s stuff, but no theory about stuff. The acquisition of stuff is not usually related to the accumulation of wealth, but there’s no doubt that items incurred in fantasy novels are in some way special. They are unique snowflakes that arrive at key times in the plot, signaling growth in the character’s identity. (Think of Will, from Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials trilogy, who grapples with moral challenges because he possesses The Subtle Knife.)

In particular, I wonder if the desire for nerds to own ‘limited edition’ consumer goods is related to the glamorization of items within fantasy worlds. Collecting limited edition ‘stuff’ has always been linked with nerd identity. Think of the cliched stereotype of the dweeb who collects mint-condition-never-removed-from-the-box-limited-edition Star Wars action figures and who can recite, in an encyclopedic fashion, their stats. These toys become a physical manifestation of one’s nerd identity. Similarly, the oohs and aahs towards those who manage to acquire ‘stuff’ from movie sets reveals a longstanding philosophy about authenticity: you got the real one. I’m not immune from the temptation of ‘rare artifacts.’ At last year’s San Diego Comic Con, I braved the Dark Horse line to purchase a limited edition (run of 1200, exclusive to Comic Con) House Stark Shield. And my views on Game of Thrones can, at the best of times, be described as ambivalent.

Of course, instead of monarchs awarding heroes with treasure, the fetishization of ‘rare’ artifacts in the primary world is mediated through private commercial entities. Limited edition consumer items are still products of capitalism–my Stark Shield was produced in a factory. (And so were the fantasy books…) Fantasy literature’s popularity is sustained by the very process it ignores or derides. ‘The capitalists’ (twirling mustache, top hat) have had no difficulty appropriating ‘items’ into the robotic age for nerds who view Comic-Con as a pilgrimage and the acquisition of special edition Lego as a quest.

But there’s anxiety within this relationship, a push-back because consumerism is just too easy. Mass production involves the masses, after all, and some fans argued that the whole-scale embrace of fantasy consumer goods is a form of appropriation rather than adoption. The former term, of course, implies an inauthentic masquerade on the part of the consumer. The latter term implies that the person is not an authentic member of the community. The perception is, perhaps, that these people are role-playing and will remove their nerd-drag once the sub-culture loses its mainstream appeal.??I cannot ignore the intersection of class and gender in this exchange. Anyone can enter a Target store and purchase a Star Wars t-shirt, but the ease of this purchase creates doubt in the wearer’s identity. Is this person really a ‘true nerd?’ Despite repeated calls for folks to quit patrolling the boundaries of nerdom, certain groups (mostly girls and women) are still required to justify their commitment to the community by, at times, being asked to respond to spontaneous pop-quizzes by self-appointed police officers of Kingdom Geek. Money functions as a good way to participate in a sub-culture that has long been defined by its rejection of irony and whole-scale enthusiasm of ‘cool stuff.’ A t-shirt from Target does not necessitate the grueling process (sarcasm—all that’s needed is more money) of purchasing a flight to a comic-con and waiting in line for several hours in hopes of acquiring limited edition whatever—the quest and the story related to the acquisition is removed, but the product is still worn as a symbol of identity, potentially allowing those with lower incomes (like young people and women) to participate in nerd sub-cultures.

Unfortunately, this participation has been met with a certain elitist attitude about what kind of labour or consumerism is good enough to qualify as being part of the community. Limited edition or not, it’s all capitalism. But to elitists, some capitalisms are better than other capitalisms. Consumerism is no longer enough because one must be a discerning consumer. And of course, testing the knowledge of other fans, often directed towards teenage girls, displays a kind of anxiety towards the opening of borders that has resulted from nerdiness’ capitalist expansion. Knowledge becomes another form of currency, the arbitrator between the high-brow collector of art and the dirty prol who can’t tell the difference between a first and second edition something-or-other.

All of which is to say that ‘fantasy economics’ has some serious real-life implications regarding inclusion, exclusion, and the powerful role of stuff/artifacts/things in identity creation. Fantasy has the potential for being highly critical of consumerism and contains the tools to imagine differently. Unfortunately, I do not think that most fantasy literature is currently engaged with these issues. Rather, pre-industrial economic practices provide convenient short-hands to indicate magic and swords—it’s a trope that some writers have confronted but most haven’t.

________

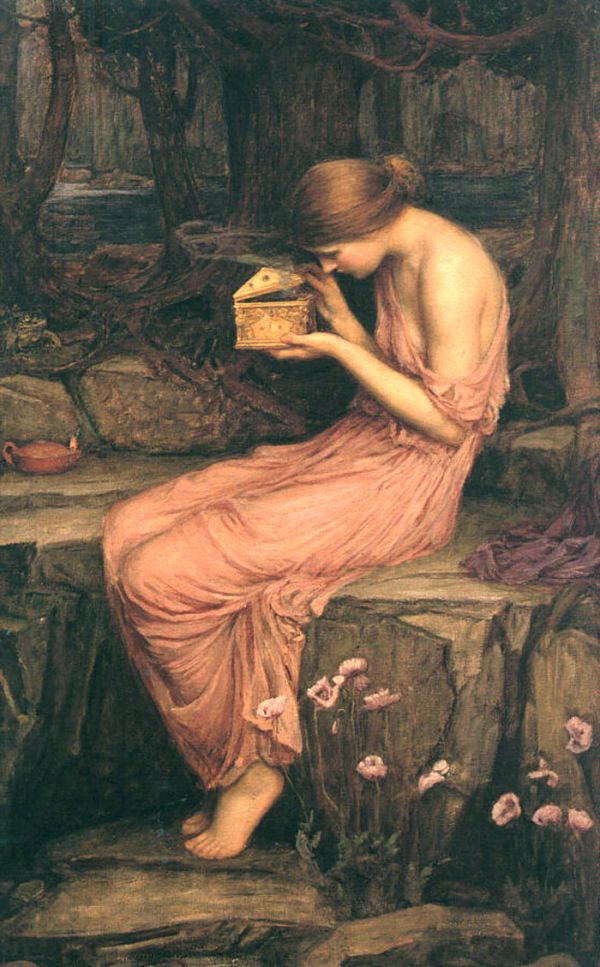

Images: John William Waterhouse, “The Crystal Ball With the Skull” and “Psyche Opening the Golden Box”

About the author: Sarah Shoker is a PhD candidate in political science at McMaster University in Canada. She’s currently completing a fantasy novel that is conspicuously absent of named swords, but she’d love you to publish it anyway. You can follow her on twitter @SarahShoker.

Being a nerd and fascinated by the industrial revolution I’ve always wanted to see more about the industrialization of magic in fantasy settings. I’m endlessly frustrated by the refusal to examine the material effects of magic on society and economics in rhose settings.

Maybe that’s why I prefer sci-fi and have little interest in collecting stuff (apart from the temptation to complete a series of books or comics).

What immediately comes to mind for me is why would I want to read a fantasy story set in a mass production environment? That seems better suited to science fiction. Mass production involves the rational, fantasy has part of its appeal by invoking the irrational and luminous.

That said one could argue that the Doctor Who universe is a fantasy story with mass production. Certainly the Tardises are mass produced as well as many baddies and don’t really seem to have any connection with actual science.

Terry Pratchett says Doctor Who is not science fiction, I don’t know what category that leaves other than fantasy. I’m thinking of this article he wrote:

“People say Doctor Who is science fiction. At least people who don’t know what science fiction is, say that Doctor Who is science fiction. Star Trek approaches science fiction. The horribly titled Star Cops which ran all too briefly on the BBC in the 1980s was the genuine pure quill of science fiction, unbelievable in some aspects but nevertheless pretty much about the possible. Indeed, several of its episodes relied on the laws of physics for their effect (I’m particularly thinking of the episode “Conversations With The Dead”). It had a following, but never caught on in a big way. It was clever, and well thought out. Doctor Who on the other hand had an episode wherein people’s surplus body fat turns into little waddling creatures. I’m not sure how old you have to be to come up with an idea like that. ”

http://boingboing.net/2010/05/03/terry-pratchett-doct.html

Also, I’ll say while fantasy can certainly critique capitalism, it has a very hard time offering alternatives, since it is perhaps by definition portraying something which is not possible.

“why would I want to read a fantasy story set in a mass production environment? ”

There are actually tons of fantasy stories set in urban environments, and they’re extremely popular. Twilight is the big example, but urban fantasy has been a big deal as a genre for quite some time.

It’s a genre that leans towards romance and a female readership, so its mainstream profile is fairly low — despite Twilight, kind of bizarrely. I’ve really never seen Twilight discussed in the context of other urban fantasy; it’s always lumped in with YA. I don’t really know what the deal is with that.

There’s probably something to say here about gender and economics and urban fantasy vs. epic fantasy…I kind of don’t know exactly what it is though. I guess one thing might be that the nostalgia for rural past and rural economy also ends up as a nostalgia for earlier gender relations (certainly in Tolkien), and one reaction to that by some female readers seems to be to embrace the fantasy without the nostalgia.

I haven’t read enough urban fantasy to know how it deals with magic objects in general. In Twilight, there aren’t magic swords; just Edward. You could say something there about different gendered relations to phallic symbols, I think.

Maybe someday we’ll do a roundtable on urban fantasy. I think it’s one of the most important genre phenomena of the last couple decades, and it seems really critically understudied, to the point of almost complete erasure.

“There are actually tons of fantasy stories set in urban environments, and they’re extremely popular.”

I meant stories where the fantasy element itself is mass produced. I am aware of urban fantasy, though not an expert on it by any means.

I was responding to the idea in the article that “Even in fantasy novels that feature urban environments, magical items are not produced through the methods of mass production.”

I simply don’t see the point of a magic sword factory, unless the writer was going for irony or satire. But one could argue the Tardis and sonic screwdriver are arguably the equivalent of mass produced magic wands.

(But recent writers have gone on to say the sonic screwdriver and Tardis factories were blown up forever, possibly due to discomfort with the idea of the fantasy element being mass produced)

Ah I see. I don’t know whether there is that sort of thing in urban fantasy or not….

You know where I did see that? In Joel Rosenberg’s Guardians of the Flame series. It was a sort of D&D riff; fantasy role players from earth end up in a fantasy setting. The characters dedicate themselves to ending slavery in the fantasy realm, and in pursuit of that they start manufacturing gunpowder; other folks in response start manufacturing magic gunpowder.

I haven’t read or thought about that series in a long time; I should look at it again. Thinking about it now, it was kind of amazing. A fantasy series in which the main goal is abolitionism (“Guardians of the Flame” isn’t a mystical reference; it refers to freedom)? Mass production of magic weapons? The main character gets killed partway through the series too; I remember it being fairly traumatic. Does anyone else remember those books?

You know where mass production of magical items and capitalism concerning said items occurs on a regular basis? Computer game RPGs, especially MMORPGs. The key difference must be the large (interactive) human element involved in the telling of those stories – more or less a reflection of “real” life.

“I simply don’t see the point of a magic sword factory, unless the writer was going for irony or satire. But one could argue the Tardis and sonic screwdriver are arguably the equivalent of mass produced magic wands.”

My argument isn’t that there *should* be mass produced magic swords, but that these items would lose their “specialness” if they were suddenly produced through the methods of mass production which, in turn, has some implications for how nerds value stuff in a capitalist economy. Authors under-develop their own economic systems, using this kind of “magical item” stuff as a trope, rather than as something they usually think about critically. Tolkien is an exception; he did this on purpose because of his disdain for industrialization. But I think most people are imitating Tolkien, rather critically agreeing with him. Again, not every author follows this trope, but it does appear to be an oft-repeated formula.

“What immediately comes to mind for me is why would I want to read a fantasy story set in a mass production environment? That seems better suited to science fiction. Mass production involves the rational, fantasy has part of its appeal by invoking the irrational and luminous.”

I actually see a lot to play with here that would potentially make a good fantasy novel! :) There are plenty of fantasy authors that spend a lot time constructing their magic systems so that they “make sense.” (And there is plenty of SF that does not make sense.) Playing with “rationality” as an idea could potentially lead to some interesting SF/F literature.

“There are plenty of fantasy authors that spend a lot time constructing their magic systems so that they “make sense. – ”

This is probably true, but as a personal preference, I don’t think it is a good idea necessarily for a writer to think of magic as an entirely rational system.

Something Kurt Busiek said on twitter that I thought was clever was:

“I kinda like the idea that magic is like what science would be like if, say, electricity only worked if it liked you”

I think that many fantasy writers are in fact nostalgic, it’s not just a Tolkien thing they are imitating. As supporting evidence I’ll say that “real world” occult magic belief system are always looking backwards to secret “ancient knowledge” from a pre industrial setting.

If you’re telling a story of secret lodges (for example say Twin Peaks) that may have more to do with Aliester Crowley than Tolkien. There’s just a lot of other sources out there.

Nostalgia for Tolkien is a kind of nostalgia…

“I think that many fantasy writers are in fact nostalgic, it’s not just a Tolkien thing they are imitating. As supporting evidence I’ll say that “real world” occult magic belief system are always looking backwards to secret “ancient knowledge” from a pre industrial setting.”

It’s true that authors draw inspiration from a variety of sources, but as I argued in an other article posted on HU (Fantasy as Subversive Literature), the continuation of Tolkien’s legacy is in part a strategy played by commercial publishers because they know what will sell. As a result, a lot of writers with Tolkien-inspired backdrops are found in the marketplace. Additionally, Tolkien is also very well known for his rigorous world-building and really did set the standard for world creation. So, as a genre, fantasy is kind of indebted to the man. That doesn’t mean that other authors aren’t important, but that it’s very difficult to have a conversation about fantasy without mentioning Tolkien.

“In particular, I wonder if the desire for nerds to own ‘limited edition’ consumer goods is related to the glamorization of items within fantasy worlds. Collecting limited edition ‘stuff’ has always been linked with nerd identity.”

This might be true but it is common in other types of collectible hobbies as well. I am thinking of specifically of sports where limited edition items can be quite popular/expensive.

I think it is more a type of person than driven by what they like. That type may be into fantasy or into the NFL (or both).

This article makes the case against Tolkien central position in fantasy, its called “Sorry, J.R.R. Tolkien is not the father of fantasy”

http://www.bostonglobe.com/ideas/2013/12/22/sorry-tolkien-not-father-fantasy/pljM6NOC54JmFaqY8bzNSI/story.html

Its clear to me that Urban Fantasy writers are usually not reacting to Tolkien by setting a story in an Urban setting, Tolkien’s contemporaries set fantasy stories in urban settings, its always been a part of the genre.

“Its clear to me that Urban Fantasy writers are usually not reacting to Tolkien by setting a story in an Urban setting, ”

I don’t know…just because folks did it in the past doesn’t mean the reasons can’t change… I don’t exactly think Twilight is about Tolkien, but I do think the having the fantasy elements in a present-day setting is a different relationship to nostalgia than setting it in a rural past would be.

Yeah maybe I wasn’t clear I’m not saying there’s no nostalgia in Urban Fantasy, I just think you can’t assume that Tolkien is some sort of central figure that Fantasy writers are all in conversation with.

Pullman is largely seen as responding to C.S. Lewis, not Tolkien, isn’t he?

Moorcock’s Elric is a response to Conan the Barbarian, not Tolkien.

Twilight is more in dialogue with Dracula than Tolkien, presumably.

Pullman didn’t really like either Lewis or Tolkien. Moorcock wrote “Epic Pooh,” where he criticized Tolkien…so Tolkien is definitely on his mind.

But the reason I quoted China Mieville is because he, purposefully, writes with urban settings and has been very critical of Tolkien in the past and his use of idealized rural life. That being said, the reason I point to Tolkien is because even when it comes to urban fantasy commercial publishers expect a high amount of rigor in world-building, a standard which Tolkien set and which has become the expectation within the industry. So authors may not necessarily draw inspiration from Tolkien, but there are certain expectations that publishers place on writers (such as rigorous world building) which can be attributed to Tolkien. Economics within the world-building process has never really been a requirement…Middle Earth got on swimmingly without really discussing anything other than treasure.

Twilight’s dialogue with Dracula is fairly attenuated. Austen and Bronte and Romeo and Juliet are closer to the surface in a lot of ways….

“commercial publishers expect a high amount of rigor in world-building”

And yet Harry Potter’s world feels like it would blow over in a moderate breeze…

I actually have to disagree with you there, but would prefer to address specifics. What part of HP doesn’t seem rigorous?

“commercial publishers expect a high amount of rigor in world-building ”

What makes you think commercial publishers expect a high rigor in world building? I’m sure you’re getting this notion from somewhere, but it strikes me as… odd.

On selling a book editor Teresa Nielsen Hayden wrote on her blog “Aspiring writers are forever asking what the odds are that they’ll wind up [selling a book]. That’s the wrong question. If you’ve written a book that surprises, amuses, and delights the readers, and gives them a strong incentive to read all the pages in order, your chances are very good indeed. ”

I think its possible to delight the readers with worldbuilding, but there’s lots of different ways you might delight the reader, and “rigorous” worldbuilding” isn’t near the top of the list, I wouldn’t think. Nor is it essential.

“This refusal to face or derive any pleasure from the realities of urban industrial life, this longing to possess, again, the infant’s eye view of the countryside, is a fundamental theme in popular English literature.”

Wasn’t this a reaction to the fact that, until the middle of the 20th century, the industrialized parts of England were heavily polluted shit holes? I’m thinking the Thames catching on fire or the London smogs that killed people in the 1950s.

If you’re stuck in that environment, prancing around in green forests would seem idyllic no matter how frequently you were going to fed on by deer ticks.

Sarah,this is a brief take on Harry Potter and my problems with it and Quidditch especially.

The fact that people’s memories are continually erased (essentially ongoing ret cons) seems emblematic. I also think there’s kind of an ethical issue with the fact that the good guys keep the knowledge of magic from the muggles, despite the fact that if the good guys lose, voldemort is going to go after folks.

There’s a similar problem with twilight; having large scale magic and many magical creatures running around with the bulk of the world none the wiser doesn’t really make any sense.

Noah, did you read that Moorcock essay about Tolkien? Boy, he really hates your beloved C.S. Lewis.

(The only Moorcock book I’ve ever read is Behold the Man, about a guy who goes back in time and finds that Jesus Christ was mentally retarded and Mary was a prostitute. I really hated it.)

I don’t really “get” Moorcock, the stuff from him I’ve read is insistently pulpy and shallow (Elric) or some sort of absurd non narrative hippy gibberish avant guarde spy mashup that seems to operate solely by dream logic- (Jerry Cornelious)

Neil Gaiman and Grant Morrison apparently loved his work as a kid, (Gaiman wrote a semi autobiographical short story called “One Life, Furnished in early Moorcock) and Alan Moore has written an essay tribute to his work, but I never really got it.

He appears to be an influential writer among a certain generation of British writers.

Here’s an interesting article in which Moorcock says he couldn’t stand Tolkien as a child and argues he is part of an “alternative fantasy tradition” not influenced by Tolkien:

http://www.theguardian.com/books/2003/jan/25/featuresreviews.guardianreview18

So Jack – why did you hate Moorcock’s Behold the Man? Too simplistic? Too consumed with a tedious straightforward hate for organized religion (a la Philip Pullman)?

The PG version of the Spaceman-Time Traveler as Jesus plot was done by EC a few decades earlier. But the really good version of the “historical Jesus” was Kazantzakis’ The Last Temptation of Christ – sadly, no spacemen in this one.

It seems like Moorcock and Pullman are united in their hatred for CS Lewis. Unlike Chris Gavaler’s fave – Lev Grossman – whose Magicians series (an urban fantasy) is filled with a mildly cynical love for the Narnia books.

“What makes you think commercial publishers expect a high rigor in world building? I’m sure you’re getting this notion from somewhere, but it strikes me as… odd.”

I could go on and on why this is the expectation, but for brevity I will say that the knowledge that I’ve acquired comes mainly from being formerly employed at a Writers’ Guild and attending a number of speculative writing workshops. It’s an expectation from the industry. Unfortunately, a book that “delights” is no longer enough, especially with the current business model being used to purchase books. Be that as it may, if you sign up for a speculative writing workshop, you can expect a sizeable amount of time dedicated to the craft of world building. That’s not to say expectations don’t exist. A number do. But it’s rare that shoddy world-building will work in one’s favour. There are practical reasons for this as well…a vague sense of time and place can become confusing to read about and create problems for situating the story. It’s not just about world-building for the sake of world-building, though there’s some of that too, of course.

Eg. http://litreactor.com/classes/urban-fantasy-101-with-joseph-nassise

http://litreactor.com/classes/the-practical-craft-of-fantasy-with-scott-lynch

http://litreactor.com/classes/become-a-god-with-delilah-s-dawson

Again, I’m not saying exceptions don’t exist.

And I really enjoyed ‘The Magicians.’ Grossman is a writer who loves Narnia but is self-reflexive enough to understand why that’s problematic…

Suat, I’m glad you asked!

First, Moorcock seemed to be going for a realistic take on the historical Jesus, but I thought the book was absurdly unrealistic. If you traveled back in time to ancient Galilee to look for a then-obscure traveling preacher, don’t you think you’d have some major communication problems? Not so in this book. The protagonist has been studying Aramaic, which naturally allows him to understand people from 2,000 years ago and vice-versa with perfect accuracy. He immediately stumbles on John the Baptist’s crew–what luck! He asks John, “So are you guys the Essenes?” and is told, “Yes, that’s exactly who we are!” He asks someone for Jesus of Nazareth’s address, gets a prompt answer, and is able to swing by for a quick visit. Give me a break.

Second, I found the Jesus-as-Idiot/Mary-as-hooker/Joseph-as-cowardly-cuckold thing to be stupid and boring, like a sullen teenager’s attempt at blasphemy. For a negative take on J.C. and friends, Moorcock could have gone in plenty of more interesting directions–Christ could have been extremely charismatic but clearly insane, or driven by both a high moral purpose and personal demons (al la Martin Luther King), or a megalomaniac cult-leader type, etc. Anything would have interested me more than a drooling idiot who can’t speak any word except for his name (which, in the book, is the Greek “Jesus,” although I think it actually would have been Yeshua).

Anyway, the book prompted me to imagine my own time-traveling-to-meet-Jesus scenario which I can share if anyone is interested.

“The PG version of the Spaceman-Time Traveler as Jesus plot was done by EC a few decades earlier. But the really good version of the “historical Jesus” was Kazantzakis’ The Last Temptation of Christ – sadly, no spacemen in this one.”

What does The Last Temptation of Christ have in common with doofy science fiction stories about how Jesus was a time traveling astronaut?

This is way off topic but they’re all toying with the idea of a fully human Jesus (and a historically placed one). In other words, they’re all conversing to varying degrees with the Arian tradition in Christianity. Kazantzakis was the only one who cared enough about this to create an intelligent, passionate book.

Mind you, the Moorcock novella won a Nebula. Maybe some of the problems Jack finds with the book can be put down to haste – Moorcock is sort of known in circles as a super-hack.

Jack, I don’t know if one’s enough for a quorum, but I’m interested in your time-traveler tale.

Thanks for your interest, John, although you can feel free to tell me if this is the stupidest thing you’ve ever heard.

In my version, two guys—let’s call them Dave and Mike—go back in time to meet J.C. Their time machine takes them to Galilee around the time when a newly discovered text says that Christ was crucified (it’s some dubious Coptic thing that links the event to a specific month in Tiberius’s reign). Like Moorcock’s protagonist, they’ve been studying Aramaic, and their plan is to make inquiries with the locals until they track down the King of Kings. Their time machine will bring them back automatically after a couple of weeks.

So Dave and Mike arrive safely, wander into a settled area, and approach some ancient Galileeans. Unfortunately, neither of them can understand a goddamned word these people say or vice-versa, and in fact, they’re not even sure that they’re dealing with Jews or Aramaic speakers. Whoever these people are, they seem very suspicious and angry to be approached by bizarre-looking strangers who keep saying, “Jews? Yeshua? Nazareth?” Dave and Mike get the impression that if they keep pestering residents of the Galilee region, they’re going to get killed.

Somehow, they make their way to Jerusalem, where they start to have better luck. Although they continue to be regarded with suspicion, at least they know that they’re around actual Jews, and they get to see the Temple in all its ancient glory. Also, their rudimentary Latin enables them to communicate a bit with some weird Roman soldiers who continually laugh at them but nonetheless give them food.

Then Dave and Mike hit the jackpot—they come across a crowd listening to a sermon by some angry Jewish guy with a small band of followers. This could be Him! Dave and Mike can’t understand what the preacher is saying, but he’s very intense and good at working a crowd. They spend a couple of days following this guy around, asking people in his audiences, “Yeshua? Nazareth?” and being ignored.

Finally, after one of the preacher’s more sparsely-attended sermons, Dave and Mike are able to approach him directly. “Yeshua? Nazareth?” they ask him. The preacher says something that they don’t understand, smiles, and gives them each a crust of bread before his followers whisk him away.

“Well, maybe that was Him,” Mike says.

“Yeah, or at least one of the people who inspired the Gospels,” Dave replies. “Maybe Christ was a composite figure. We may have just met one-third of Jesus.”

“I guess the origins of Christianity will forever remain mysterious, even with the benefits of time-travel technology,” Mike muses. “Son of a bitch, what a goddamn motherfucking waste this trip was.”

Later that night, the time machine takes them back to the present.

But about a month later, Dave and Mike meet at a local Starbucks to debrief. And after a few minutes of polite chit-chat, Mike drops a bombshell.

“I don’t know about you, Dave, but since we got home, I’ve come to realize that the guy we met actually was Jesus Christ,” he says. “Not only that, but I know for a fact that He was crucified and rose from the dead shortly after we met Him. He was the Son of God and redeemed all of humanity. I’m a Christian now.”

“Mike, what the hell are you talking about? Where are you getting this from?”

“Dave, it was the sparkle in his eye when he gave us that bread. Didn’t you notice it? It was a sparkle that said, ‘I know exactly who you guys are and why you’re here. And yes, I’m Him. The Gospels are entirely true, and I am your Lord and Savior.’”

“No, Mike, I didn’t see any fucking eye sparkle that explained all that. And if he was an omnipotent being who knew who we were and wanted to convert us, wouldn’t he have communicated with us in English, rather than in eye sparkles?”

“It wasn’t just the eye sparkles, Mike! He told us who he was through his very manner! I got an incredible sense of kindness and peace from him! I know that I was in the presence of the Savior! Didn’t you feel anything special from him?”

“He seemed nice, but the crazy Romans we met actually seemed a lot nicer. The Gospels don’t even portray Jesus as kind and peaceful, anyway. Plus, they contradict each other and have enormous plot holes. Do you think the guy we met was born in Bethlehem because a Roman census required his parents to return to their birthplace, even though the historical record says that’s total bullshit? Jesus Christ is right. I don’t know whether the time-travel experience has warped your mind or I whether travelled back in time with a complete idiot, but either way, this is disturbing.”

“Well, I can’t prove that we met Jesus or that he was the Messiah,” Mike grants. “It comes down to faith.”

“Yeah, we agree on that much,” says Dave.

So that’s it. Sarah, apologies for hijacking your comments thread!

Not at all, I enjoyed reading it! :)

Sarah, thanks for being so gracious. I hope it’s all right if we continue in this vein.

Jack, thank you for doing this. I want to respond with one of my typical, long-winded comments, but I have no time today, so expect it tonight or tomorrow! (I’m just hoping I don’t kill another thread.)

Seems like there’s something to be said for the role of Dungeons & Dragons and it’s innumerable descendants in the “stuff” aspect of fantasy. In traditional play the game is all about acquiring stuff. Sure it built on existing fantasy/s&s fiction, but D&D made it more about active acquiring for the player/reader/fan, which has totally come down to the present via video game culture (like all the “achievements” I seem to get for reasons I don’t understand when playing games like Mass Effect, but which seem to have some kind of virtual stuff, collector aspect to them).

Reminds me that the default setting presented in most D&D manuals is a pseudo-medieval/renaissance world that would quickly fall apart if the actual rules regarding magic and magical items were applied with some common sense .

Roleplay nerds have been trying to figure out how and have arrived at a sort of industrialized magical society that looks much more like a dystopian Sci-Fi setting than anything from high or low fantasy. Of course the end result depends on more than just the economic potential of the magic available but agrarian feudalism seems very unlikely.

Jack, here’s my response to the story outline you posted. Thanks again for sharing it.

I really liked the bit with the Roman soldiers. Dave and Mike would have been just the latest example of Judean weirdness to Westerners in a culture those soldiers did not understand. Their reaction — amusement, combined with convenient charity that helps the nuisance “move along,” seemed both entertaining and perfectly plausible.

I was less satisfied with the difficulty Mike and Dave had with making themselves understood. Aramaic has varied widely over time and geography, so I agree with you that the ease with which Moorcock’s protagonist communicated is incredible. However, I think there are enough Old Aramaic documents (such as the records of the Achaemenid Empire) for linguistic scholars to have given Dave and Mike the vocabulary and syntax to function, albeit with difficulty. I can’t justify this perception with documented sources, but that would be my guess.

Regardless, I think D & M would have found a Yeshua of Nazareth, even if it wasn’t Yeshua Bar-Maryam, the itinerant preacher. As you probably know, “Yeshua” is a contraction of “Yehoshuah,” which is also translated “Joshua” and means “Yahweh saves.” Yeshua was a common name in early first century Judea, just as Sarah Connor was in late twentieth century Los Angeles.

I liked the distinction you drew between the nice, unchallenging Jesus of popular perception and the Jesus of the Gospels. In the Gospels, Jesus advocated and practiced forgiveness, loving one’s enemies, and foregoing resistance when wronged (The Sermon on the Mount in Matthew 5-7; the capture in the Garden of Gethsemane and the pre-crucifixion trial narratives in all the Gospels; Luke 23:34). However, he also castigated the Judean religious leadership for hypocrisy and exploiting the populace (too many references to mention). He initiated violence in the Temple (Matthew 21, Mark 11, John 2), and he advocated self-defense when necessary (Luke 22:38).

I don’t think the differences between the Gospels are as serious as Dave portrays them to be, although we’d have to cite details to have a real discussion on that point. To me, none are doctrinally significant, and they tend to be well within the differences I expect between separate eyewitness testimonies (much of Matthew and John, as attributed) and between accounts by non-eyewitness biographers (Mark and Luke, as attributed). There are many works that reconcile the apparent differences. One notable exception is the census.

Your commentary on the census motivated me to do a lot of research, so thanks for making me more knowledgeable. Some of the reported historical discrepancies with the census, such as the assertion that the Romans would not have had Joseph return to his ancestral home, have been resolved by archaeology (e.g., the decree of Gaius Vibius Maximus, Prefect of Egypt). I can go on about that particular complaint and the necessity for family-related censuses in the Middle East then and now, but I doubt anyone wants me to. The real problem is an obvious timeline issue. Matthew says Herod the Great (death in 4 or 5 B.C.) was King when Jesus was born. Luke says “The first registration took place while Quirinius was governing Syria” about ten years later. This discrepancy is made more unusual by the fact that Luke is generally regarded as a highly accurate historian. I found a variety of explanations. Some, to me, seem tortured and desperate, such as the syntactic argument that Luke meant before Quirinius’ governorship, not during. Others seem plausible, but they await archaeological evidence to be confirmed. The one I like best is that the census was finally complete while Quirinius was governor, but had begun years before, under Herod’s reign. Augustus ruled the Roman Empire the entire time. He liked censuses and initiated multiple, but they were expensive, difficult, and easily stalled by unrest. Consequently, a difference of ten or fifteen years from start to finish is plausible, especially if they went by region or by tribe in succession. However, this is still conjecture. I’m willing to wait for archaeology to reveal more information, given Luke’s reliability on all other historical and geographical details, the fact that such an error would have been glaring to Luke’s audience, the incompleteness of the historical record, and admittedly, my own personal bias.

Perhaps the most jarring event in your outline is Mike’s conversion. From my perspective, it seems like a bad caricature of the experience of becoming a Christian. To you, it may be an accurate description of what it seems like when people you know decide to follow Christ — i.e., the sudden, inexplicable onset of insanity. In your defense, the Gospels do present Jesus as 1) sometimes angry, 2) intense, 3) good at working a crowd, and 4) occasionally feeding people who showed up at his sermons (sometimes related to Item 3). Furthermore, Mike and Dave represent two of the three standard reactions to the good news of Christ that the New Testament records: acceptance, rejection, and “I want to hear more about this” (Acts 17:32-34). Finally, I think most Christians would accept the description of their conversion experience as an encounter with Christ — not as tangible or externally visible as Mike’s encounter, but an encounter nonetheless.

A couple of things still disturb me, though. One is that Mike’s reaction during the encounter (“What a… waste of time”) doesn’t jibe with his description of his perception after the fact. Based on the reaction of new disciples and others in the Gospels, I would have expected Mike to have been awestruck or at least troubled by Christ’s authenticity while still present with him. It could have taken him some time to process this and decide what it meant, but his utter dejectedness on the scene seems inconsistent with his later decision. Maybe I’m just suffering from too little information, and the conflicting emotions I’m looking for would have been apparent in the full story. Second, I’m with Dave. I’d like this major life decision to be based on more than just demeanor and eye sparkles. That could be vanity on my part, since I like to believe my decision had stronger foundations. At the time, people followed Christ because he spoke with unique authority and discernment, because he was morally uncompromising even in the face of opprobrium and physical danger, and because he performed miracles. Even the ancients who wrote against him mentioned that miraculous deeds were attributed to him. All that probably added up to some powerful charisma, but I do not recall a reference to eye sparkles.

Thanks again for being open to a response. I enjoyed reading your work, and I learned a lot preparing the review.

John, thanks a lot for giving my story/outline such a thoughtful critique (probably more thoughtful than it deserved).

Although I was trying to emphasize that religious experiences and beliefs are subjective, I didn’t mean to portray conversion to Christianity as an outburst of insanity. I’m not a Christian, and the story is probably slanted toward the unbelief side, with all the quibbling about the historical accuracy of the Gospels. But on a subjective level, Dave can’t disprove that Mike had an important experience, and he also seems like a jerk compared to Mike.

I’m not that knowledgeable about the search for the historical Jesus, so I can’t respond much to your census discussion. I’ve heard multiple critics of Christianity describe the return-to-Bethlehem requirement as ahistorical (Christopher Hitchens did so in his snotty atheism bestseller, for example). But for all I know, you could be right about its accuracy. I’d like to read a lot more about the subject.

You’re right that the “what a waste” line contrasted too sharply with Mike’s later conversion, but I do like the idea of a delayed conversion experience. When it comes to traumatic events, people often have long-term reactions that differ greatly from their initial reactions, and I think it’s possible to follow a similar path after a positive event.

Thanks again!

Concur 100% on your delayed conversion logic, Jack. I’m glad you appreciated the review, as I appreciated your story.

The edict I referenced is about a census in Roman-ruled Egypt where the prefect similarly told everyone to go home to be counted. Even to this day, you can’t really identify anyone in the region except as they relate to family and tribe. This was even more closely linked to land in Judea, since Israelite law forbade permanently selling tribal land. Identification was key for normal Roman bureaucratic reasons, but I would bet the Jewish cultural tendency toward insurgency made knowing whom you were dealing with even more important. Occasional HU writer Kristian Williams could probably write better than I can on the long history of censuses as measures to enable counterinsurgency.

Regarding Hitchens, I completely agree on the tone of that book. He was a poor ambassador for atheism. He accused Christians of believing things I didn’t believe, and that nobody I knew believed. It was frustrating to be so misrepresented. I felt like he was always arguing against a distorted strawman of his own invention.

Pingback: Tuesday Links | Gerry Canavan

This section seems confused to me:

“Part of the hero’s journey may involve a quest to recover certain items, yet the acquisition of stuff in fantasy literature is not about consumerism but a reflection of the protagonist’s righteousness or destitution. In Beowulf, for example, treasure is used to secure loyalty and ensure the continuation of a just society. Further examples include the destruction of the One Ring, the destruction of the Seven Horcruxes in order to defeat Voldemort and the search for the Deathly Hallows, and The Sword in the Stone– an object which arbitrates rightful inheritance to the throne.”

If you want to argue that there’s a major fantasy-trope in which a protagonist seeks out some magical object, either to gain magical or temporal power, and then compare that to nerds’ desire to own unique stuff, that’s fine so far as it goes.

But what does the destruction or negation of items deemed dangerous to society have to do with acquisition? Unless you want to take this in the direction of Bataille and destruction-rituals, but I don’t think that’s even implied.

Tolkien’s use of the One Ring, as well as the Arkenstone in THE HOBBIT, are highly ambivalent. The items have an undefinable charisma, but the One Ring can be used to bind the minds of others, and Thorin is willing to fight all comers for the Dwarf-treasure, refusing even to surrender even a fraction of it. Tolkien gives Thorin a somewhat heroic death by bringing in an army of evil creatures, but had the Dwarves been forced to fight the Elves who wanted a share, he wouldn’t have looked quite as noble, and indeed he dies regretting his greediness. Bilbo tries, without success, to use the Arkenstone to avert a conflict. How does that relate, if at all, to your paradigm of “righteousness or destitution?”

And yet, imitations of the One Ring are sold to great commercial success. People acquire all sorts of things, even outside of nerdom, that are harmful. But these items still have, as you say, charisma. There’s no doubt that the One Ring is important, only that some find its properties evil. But it’s its importance that’s key here, I would argue.

And yes, that is absolutely related to moral “righteousness” OR “destitution.” Items either reflect moral superiority or bankruptcy. And some people always prefer to set their alignment to chaotic evil.

But even if an item like the One Ring symbolizes what you call “destitution” or “bankruptcy” within the text, that doesn’t parallel the way replicas of the One Ring are valued in the Real World. They are prized for the same reasons people like villains even though they’re evil within the text: to the audience, evil items and villains are part of the machine that makes the story go.

So your examples of the One Ring and the Horcruxes don’t line up as well as your parallels between sacred swords and sacred doodads.

I respectfully disagree. Considering the One Ring and Horcruxes are symbols of hoarding and power(Dumbledore mentions that Voldemort has a magpie-ish obsession with collecting things that have magical/symoblic importance…he displays this trait even as a young boy), I would actually argue that the desire for accumulation within the real world is represented quite well by the way these items are conceived in the plot. “Nerds” want these items for their symoblic link to what they find important–which is exactly what Voldemort does with his selection of containers for his horcruxes. Remember what Dumbledore tells Harry…Voldemort doesn’t randomly select the items in which he plans on storing his horcruxes; they need to be special in some way and that’s why Voldemort chooses items that have links of grandeur with the Hogwarts Houses because he wants to be ‘special’ (all of which was entirely ignored in the movies, of course.)

I think there is something of a critique of acquisitiveness in LOTR, though; the desire for power (symbolized by the desire for the One Ring) is seen as destructive and evil. There’s a tension there maybe with the love of and fetishization of magic swords and items of power.

Basically, you could say there’s a tension between the Christian impulse that laying down power is the true power, and a more pagan enthusiasm for power and acquisition itself. It’s like Frodo at the end refusing to do violence, and that being very ambivalently treated in the text (where Frodo is the moral lodestone, but violence still ends up as the way to win back the Shire.)

This brings to mind something that Hayao Miyazaki said about Lord of the Rings. When asked what he thought about it, he replied with something along the lines of “I would much rather read a book about the Orcs.” This comment made me think of the possibilities of that story, and I realized how unlike other high fantasy such a story would be,as it would have to deal with slavery, blind race hatred(on both sides), class wars between the factions and many other rather industrial age topics. It seems like something ripe for the picking for writers to play with.

And Noah, I have always been interested in Frodo as depicted in The Return of the King. He comes across as something to pity more than a hero. He traveled all the way across middle-earth only to fail his quest in the end, along with suffering mental damage and physical. His return to the place he thought of as home, a place free from the malice of the greater world, only to discover it has been affected just the same as the rest, it seems like he was trying to be greater than he really was when he tried to forbid violence during the scouring of the shire. It is like he was afraid to fail again as a hero, which is what he continuously did throughout the entire story. I have always loved how vulnerable and pathetic Frodo feels as a hero. There are so many instances in the trilogy in which he brings run upon himself or he wavers. Sorry for the lack of relevance, but your comment brought up something I have long thought about. Many people I know who enjoy lord of the rings hate frodo, and yet for me he is the only character I really love. The others, apart from maybe boromir can sometimes feel so inhuman. I guess readers of fantasy tend to enjoy characters who do not fail or succumb to weakness, where frodo is ultimately beaten by the quest and has to leave for the houses of healing.

That’s interesting; I never thought of Frodo as failing. Definitely as suffering from PTSD though; I think the parallels with WWI shell shock have been much discussed, and were almost certainly intentional.

“I would much rather read a book about the Orcs.”

I second that. Or rather, “The Origins of Mordor’s Industrial Revolution, 1750-1850”. Oh that would make me clap with joy.

I completely agree with Sarah that it would be AMAZING if there was more economics in fantasy settings. More pre-capitalist economics would be great, but fantasy set during a time of transition to capitalism would be even better. Just imagine all those heroic-age and feudal tropes getting burnt at the stake. The young village boy/rightful king on his quest to reclaim the throne would get thrown in the workhouse for vagrancy. And when he finally got the crown on his head he’d realise that most of his power had been transferred to a parliament of rich landowners who were busy enclosing his old village land, thereby forcing his beloved childhood friends into the new mills to work twelve hour days making cloth for uniforms for export to the army of the enemy nation he now has to wage war against to save his homeland. Yeah!

I was always annoyed that the Scouring of the Shire happens because an evil wizard arrives out of the blue and turns it into an industrial hell-hole with a click of his fingers. It seems like such a lazy critique of industrialisation. Similarly with the dichotomy between the orcs’ industrialism (evil) and the dwarves’ and elves’ artisanal industry (to be revered). (And all the class-judgement implications involved). Super lazy.

The best example of an involved fantasy economics I can think of off the top of my head is Le Guin’s Always Coming Home. I guess authors only find space to include economics when stories are about people leading real lives. If they are busy trying to save the world (again) then there just isn’t going to be time to chat about everyday marketplace interactions or the minutiae of global financial systems. Sigh.

Man, I still haven’t read Always Coming Home. Someday…

I talk about the orcs some here.

I can see how it might not seem like he failed, but I cannot help but feeling like he did. he constantly fumbles throughout the story barely scraping by until reaching the cracks of doom where he claims the ring and fails in his quest. The only reason frodo “succeeds” is because of gollums unlucky fall into the fire. I think just saying he succeeded but was damaged is to fall short of how pitifully tragic and unheroic Frodo is. He not only fails in his quest and succumbs to the ring, but is also damaged by the journey. I think this whole route of thought began for me the first time i read the books, and I was taken by how frodo considers abandoning his friends to die. My example of this would be the Barrow Downs sequence in which he considers putting on the ring, but decides against it due to guilt. I was a bit shaken that the hero would think of this, especially in a book full of sacrifice and full on death charges. This led me to begin examining how often frodo stumbles, and comparing that to how often he succeeds and the stumbling/outright failing far outnumbers his successes. Anyways enough of this off topic stuff, just wanted to share some thoughts on the books

Also Noah, I remember reading that article when you wrote it. It is interesting to think of the genocidal acts of the “good” races as being heroic. Honestly though, i never interpreted the book that way. I always sympathized with the orcs as much as the other races, and I feel Tolkien gives us a decent set of reasons for doing so. Any scene with orcs interacting seems to suggest racism and class issues within their rank, and they also seem to live in complete fear of whatever master they are serving. They are pitiable slaves really. And at last when they are freed they are hunted down and wiped out. But then, they have also been nagging at and harassing the other races for as long they have existed, so it only seems natural that the others would finally succumb to a desire for total revenge. Honestly though, I have always felt that the race that is actually in many ways worse than the orcs were the dwarves, selfish treasure hoarders willing to kill and loot for precious metal. Thorin, in The Hobbit is really not much beyond an asshole as far as characters go, until the very end of his life when he sees that bilbos desire for peace is worthy of attention. But before this he was fully willing to massacre men and elves. But really, all of the races in Middle Earth end up being foul at some point in their history, some just more so than others.

The only true racism I see in the books are the lack of ethnically diverse heroes. All african/asian/middle-eastern peoples are presented as evil. This always struck me as the racism that is not so much “these races are bad, so I must present them as bad”, but is more “All of my friends are white, and I am white, so I will make my heroes white” which is still racist, but maybe not as despicable? I have never read any of Tolkiens thoughts on race, so excuse me if I am incorrect in my assessment of him.

“‘The Origins of Mordor’s Industrial Revolution, 1750-1850’. Oh that would make me clap with joy.”

I’d suggest reading The Last Ringbearer by Kirill Eskov. It’s a revisionist telling of the Lord of the Rings and it suggests that Mordor’s impending industrial revolution was a threat to the imperialistic factions of Middle-Earth led by Gandalf. It’s a pretty interesting read.

Wow; that sounds amazing. Looks like it’s available in English here.

“I’d suggest reading The Last Ringbearer by Kirill Eskov.”

Oh wow. You’ve made my evening. See you in a few hours.

And Noah, really!?! You haven’t read Always Coming Home? It’s the distilled essence of Le Guin. My favourite book of hers by far.

Nope; I’ve read Earthsea (even the last crappy one), Dispossessed, Left Hand of Darkness, Word for World is Forest, poetry, essays, stories, Rocannon’s World, and maybe another Hainish cycle or two, but never got to Always Coming Home….

Another tangential point concerning Moorcock’s putdown of Tolkien’s “infantile”, pastoral and rural outlook … if you grew up, lived and worked in a rural, pastoral environment, Tolkien is not infantile, he is describing reality.

The deformation of humanity by the imposition of machines and money is astonishing: reality becomes infantile, nature becomes alien and the intense bond between oneself and nature becomes a monetized embarrassment.

I’ve just read an interesting YA fantasy called ‘Summoner’ that’s set in a Tolkienesque world on the cusp of industrialisation. The implicit consequences are just beginning to be felt. For instance, the dwarfs have a monopoly on firearms, and are less willing to be treated as a subject race by the humans. Firearms lead to a de-skilling of combat (as was the case in the real world) and threaten the primacy of the aristocracy, the only masters of battle magic. Meanwhile the demands of industry lead to human invasion of the Orcs’ resource-rich lands…etc.

Mahendra, it seems unlikely that Tolkien is describing “reality” in rural England, circa 1900 when he describes the Shire.

For one thing there’s no religion and no women (save one old shrew).

One they leave the shire it’s more like olden times or something- there’s castles and knights, surely not the world of his childhood.

If you’ve ever lived and worked on a farm, you’ll notice the absence of women very quickly. You certainly have a point with religion but my idea was rural in the sense of nature and human beings living with animals and plants and the earth around them.

That’s country livin’ for me, Zsa Zsa.

I get what you’re saying, there was a hierarchy, but both of my grandmothers grew up as sharecroppers. Poor people needed everyone to work for the family to survive. Don’t know about England, but that was the case in Oklahoma and Texas. Women were very much a part of the hard labor of farm life.

Frodo and Bilbo don’t work on farms. The Shire is like a small English town, isn’t it? There are outlying farms, but that’s not where Bilbo and Frodo live. They live in a town and the neighbors gossip about them. They are upper class and don’t work for a living. They have no female friends- no mothers (Bilbo’s is maybe mentioned, but is long since dead?), no daughters, no sisters, there are basically no female hobbits that we meet. (They presumably exist) From what we see Hobbits are almost like the male only smurfs or something.

Tolkien begrudgingly mentions Sam has a wife after leaving Frodo’s service, so they he can give Sam a happy ending. (Not sure if she has any lines of dialogue?)

I think you’re really stretching things to claim Tolkien is trying to be authentic. Pretty sure he didn’t spend his childhood in a hold in the ground?

They’re not really upper class. Middle class. Tolkien himself pointed out the link between ‘hobbit’ and ‘Babbitt’. Pippin’s upper-class, though. And he’s the one who leads the fight against Saruman during the Scouring.

I guess it depends on how you define middle verse upper class, but doesn’t being a property owner who doesn’t have to work for a living make you upper class? (neither Bilbo or Frodo have careers, do they?)

(Plus Frodo has a servant, even if it is one acquired in special circumstances)

Pingback: Tuesday Links | Occupy Wall Street by Platlee

Pallas:

“but doesn’t being a property owner who doesn’t have to work for a living make you upper class? (neither Bilbo or Frodo have careers, do they?)”

No, it just means you’re a rentier. Class is not defined by wealth. A tramp in the streets can be higher in class than a billionaire if he’s of the right birth.

The thing is, you’re taking a New World approach to class. Don’t forget that Tolkien was English…

And before the Second World War it was quite standard for even lower-middle-class people to have a servant.

When I saw the header “Economics in fantasy literature” I immediately thought this was going to be about Spice and Wolf, which is about 1/2 fantasy/romance to 1/2 late-medieval economics. The manga and anime adaptations tone down the economics a bit, but it’s still all about long-distance trade, profit margins, currency devaluation, credit and loan arrangements between merchants and traders, etc.; basically Preindustrial Economics 101 with with nekkid wolfgirl boobs (because it’s for guys). It’s quite interesting as a thing, although I wasn’t taken by it as entertainment (and the generous helpings of fanservice didn’t help).

Alex – who is Summoner written by? Amazon lists at least six books by that name. Including ‘monster and demon erotica’, which I presume is not the one you’re talking about. Maybe.

Hywel: it hasn’t been published yet! I write manuscript reviews for a literary agent. Yeah, Noah, I’ve joined the ranks of freelance writers…not the Land of Milk and Honey by any means.

Pallas, a final confirmation that Frodo is not an aristocrat, but middle-class: Sam calls him “Mister Frodo”.

Only commoners are called ‘Mister'(Mr) or ‘Mistress’ (Mrs): it’s an insult to address an aristocrat thus.

I’ve been meaning to read The Last Ringbearer, I don’t think Tolkien’s distaste for industry is wholly bad but it sounds like an interesting perspective.

As for a story from the orcs’ point of view there is a novel called just Orcs by Stan Nichols where the intent was supposedly to throw a sympathetic light on them but from what I hear it’s terrible and doesn’t achive its purpose. Didn’t bother with reading it after hearing that.

Pingback: Notes from the Anthropocene: Insuring the Apocalypse and Other Links | The Hyperarchival Parallax

Pingback: Notes from the Anthropocene: Insuring the Apocalypse and Other Links | Gaia Gazette

Pingback: 78 Creating Background with Turbofanatic | The Kingdoms of Evil

On the subject of mass-produced magic, Terry Pratchett’s Discworld goes for it. Not magic swords, because most people don’t need swords, they tend to pick up a bit of magic anyway because it’s sort of like magnetism, and wizards have noticed that the sort of people who like powerful magic swords tend to use them on wizards.

But things people might find useful, like imp-powered cameras and PDAs are clearly mass-produced, even if exactly *how* they’re mass-produced is glossed over. And there’s mundane mass-production as well, with candle and condom factories.

Of course, this is a bit of a satire on how inappropriate to a fantasy world it seems. As Sir Terry says, you can’t imagine a condom factory on Middle Earth and it’s probably blasphemous to have one in Narnia.

I find this a fascinating piece, not least because of all the time I spent on it myself. I even created an analog for Adam Smith (Duncan MacY) in my fantasy world ‘the Sundered Spheres,’ and the world is in the beginnings of a renaissance/industrial revolution based on magic and Duncan’s writings. For example candles and lanterns are vanishing, because ‘mage-lights’ have become so common and cheap that even poor folks have them in their homes. There is such a thing as a ‘magical manufactory.’ What’s more, learning magic has become more common too; everybody knows a few ‘household cantrips’ when only a few years earlier only the educated elite knew any magic at all. The family of the protagonist in ‘Errant Knight’ is actually secretly engaged in trade, but the secret is becoming an open secret though the errant knight himself doesn’t know about it. Even so, in his wanderings he learned about the importance of trade even to the most remote towns and villages and spends as much time as possible chopping up bandits and pirates, the ultimate enemies of capitalism.

It’s a hard thing to add any economic ideas to a fantasy story, but I did it because Adam Smith had more influence over my ideas than JRR Tolkien, though I’ve read ‘The Lord of the Rings’ many times more than ‘Theory of Moral Sentiments’ and ‘Wealth of Nations.’ What’s more, I can’t see the world–any world, not even a fantasy world–actually getting rid of the natural economic order, which is usually (and incorrectly) called Capitalism. Capitalism still makes China and Cuba function, despite their supposed allegiance to Marx.

I have only three novels published on Amazon so far, but one of my early attempts is about the son of a merchant prince with a talent for adventure, and the first part of the story includes a lot of economic activity. That’s available on Wattpad for free: http://www.wattpad.com/story/2827944-a-ghost-of-a-desire

I will also add that David Eddings includes a lot of commercial activity in his ‘Belgariad’ and ‘Mallorean,’ which is one part of those stories I always enjoyed, even though they make something of a caricature.