“Without myth, however, all cultures lose their healthy, creative, natural energy; only a horizon surrounded by myths encloses and unifies a cultural movement.”

The Birth of Tragedy, Friedrich Nietzsche

Isabel Greenberg’s widely lauded The Encyclopedia of Early Earth is a tale of love, myth, and storytelling. Here are Judaic legends, nods to the epic poems of Homer, a smattering of creation myths and various versions of the known world retold, expanded, and reorganized.

The editor and narrator would appear to be a young man from The Land of Nord which is the North Pole for all intents and purposes; but, as with most things in Greenberg’s comic, this becomes the subject of syncretization. The word “Nord” is not only a premonition of our hero’s initial travels through a Nordic landscape but is also a near homonym for the land of Nod, east of Eden—a byword for wandering. For this is our storyteller’s secondary calling as he sails and paddles in uncharted waters through the lands of a mythical Europe and Babylon to a strangely inhabited South Pole.

This is all part of Greenberg’s deliberate act of subterfuge, mystification and reimagining; making old things new in a world grown weary and overly familiar with our immediate legends and even those of our neighbors.

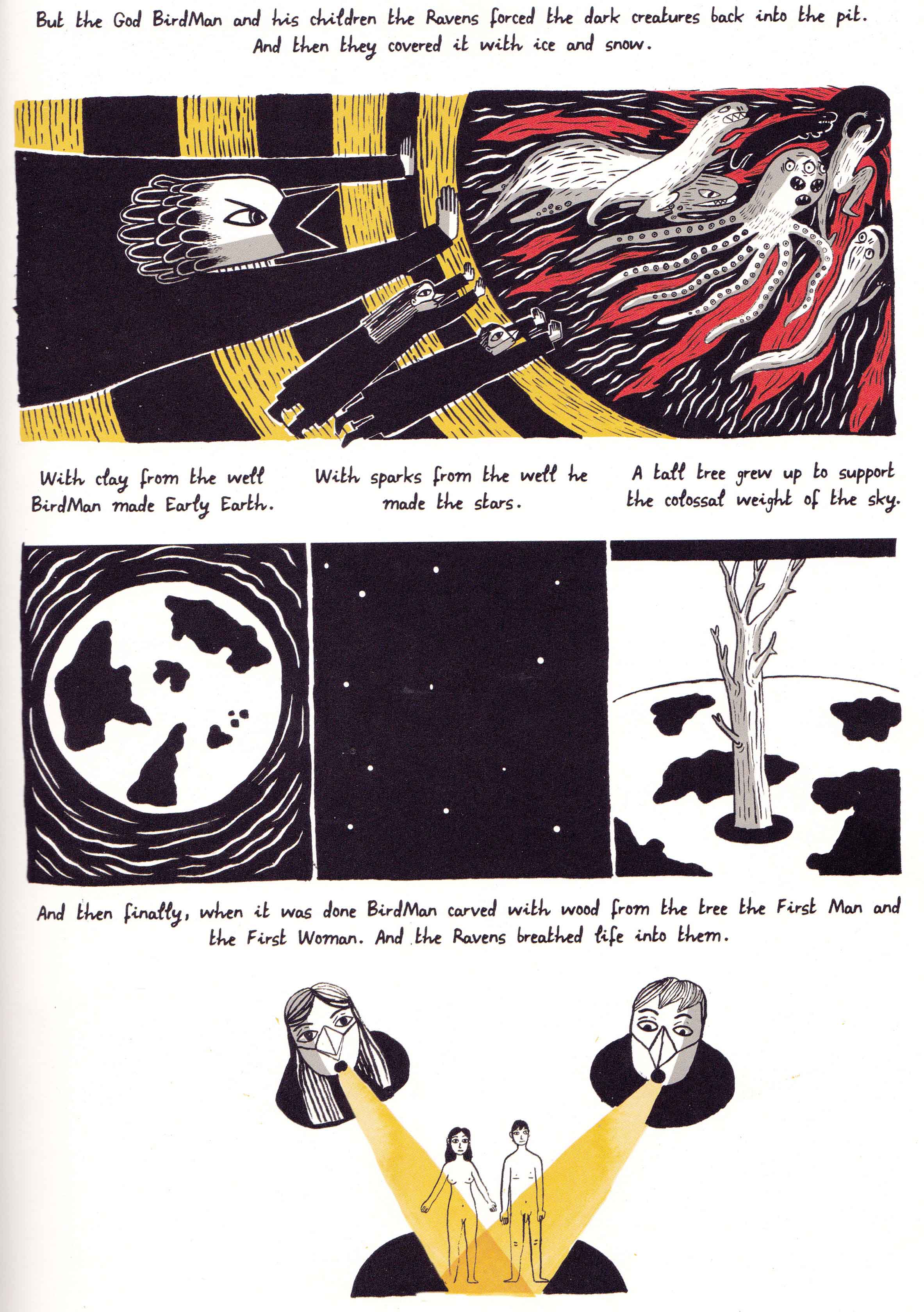

New words are added on to existing myths deepening their perspective—the Well of Urd (destiny) is now called the Well of Life but the world tree, Yggdrasil, remains as a familiar guiding post. The triad of gods who created the first man and woman of Norse mythology (Ask and Embla) remain but soon become affixed to a retelling of the tale of Cain and Abel. This Arian trinity—the Eagle God and his two Raven children—might be connected with the raven god of Inuit legend and the thunderbird but they are also Huginn and Muninn astride Odin’s shoulders, the ravens of biblical stories and perhaps even the winged disc (faravahar) of Zorastrianism.

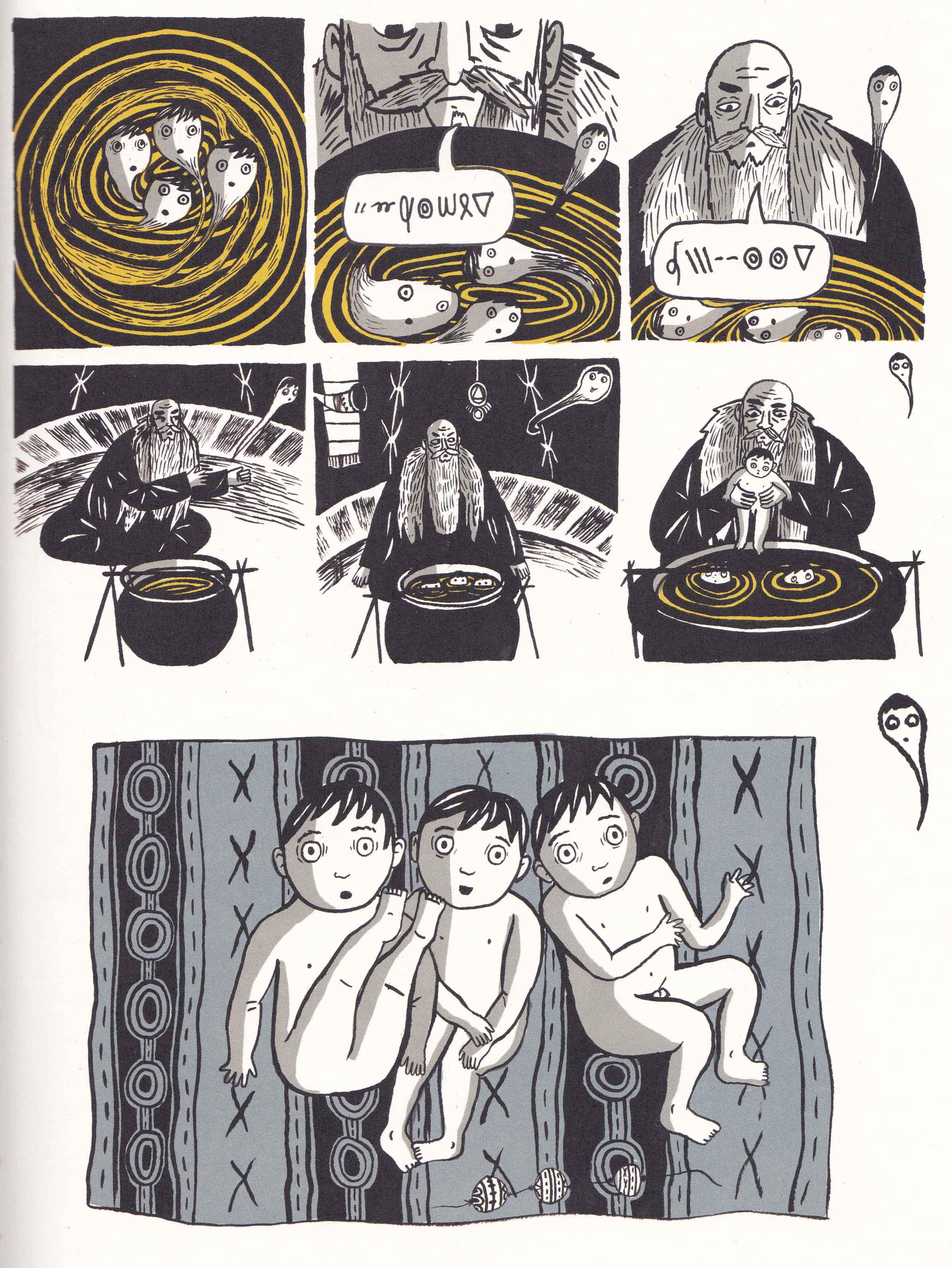

In Greenberg’s opening story, “The Three Sisters of Summer Island”, the eponymous sisters find a baby boy “along the banks of the Sky Lake.” Unable to decide who should care for the baby, they consult a shaman who helps them divide the boy into three parts, each containing a different aspect of his soul. By displacing the more familiar tales of child rescue or abandonment (those of Moses and Sargon) and through its setting in the frozen north, the story manages to retain echoes of the legends concerning Sedna—the giantess and mistress of the seas and underworld of Inuit myth whose fingers when cleaved from her body became seals, walruses, and whales (in some versions, salmon or different species of seal).

The three sisters of Greenberg’s story—Gull-Wing who is “brave and headstrong”, “River-Reed who is “always laughing”, and First-Snow who is “thoughtful and wise”—might be seen as a minor borrowing from the three sisters of the Iroquois creation myth (corns, beans, and squash), taken away one at a time by a mysterious visitor to their fields before being reunited at its conclusion; but they really partake of any triad of brothers or sisters in European and Middle-Eastern folklore.

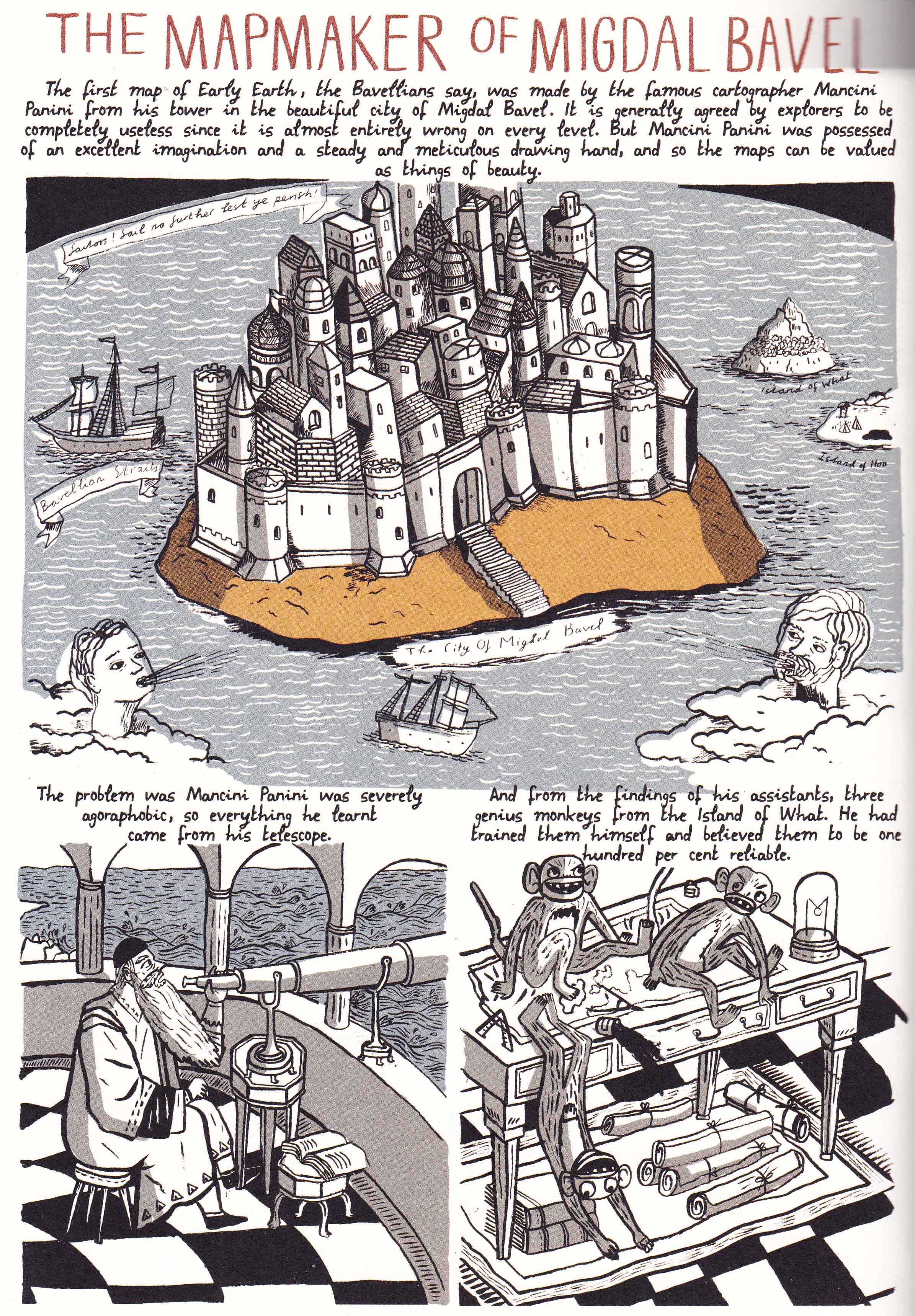

Greenberg’s settings are largely divorced from factual history, indulging instead in the artistry and inventiveness of medieval drawing and maps. Perhaps marginally more precise and truthful then the work of the solitary cartographer of Greenberg’s tale who never leaves the palace in Migdal Bavel, inventing dangers and destinations out of whole cloth; but really deriving from the same space—the isolation of the artist.

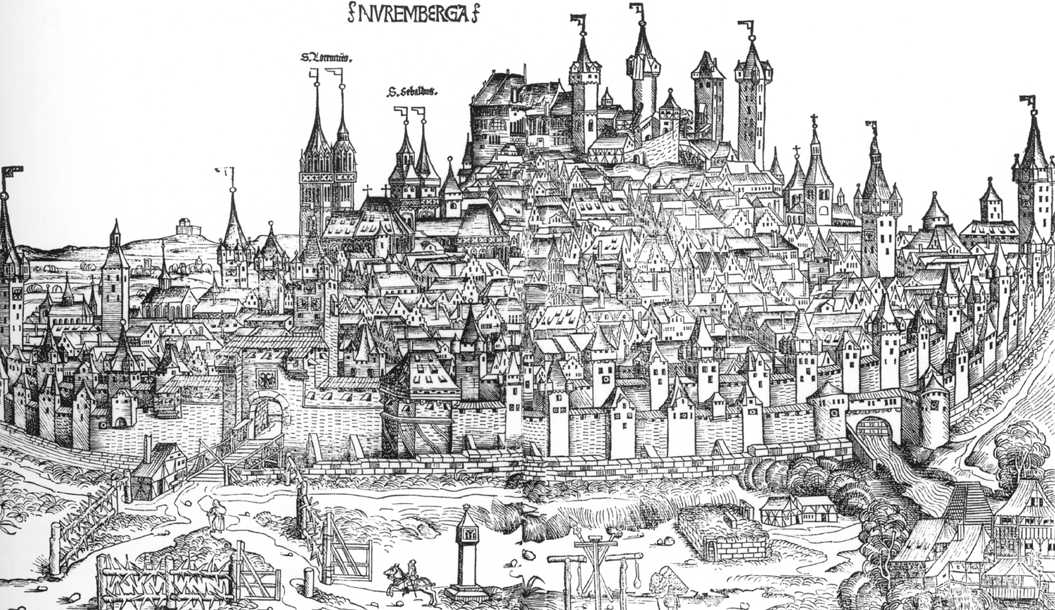

Migdal Bavel is itself a medieval Babylon resting comfortably in the arms of biblical legend and the art of the medieval illustrator. The chapter titled, “The Mapmaker of Migdal Bavel” brings to mind famous incunabula like the Nuremberg Chronicle or Braun & Hogenberg’s Civitates orbis terrarum. The former book, like Greenberg’s comic, is an illustrated world history taking inspiration in parts from the Bible.

The whale which swallows the storyteller towards the close of the comic is not merely the big fish of the Book of Jonah but is cut from the same cloth as “the earliest maps with sea monsters” —the Beatus Mappaemundi (see Sea Monsters on Medieval and Renaissance Maps by Chet Van Duzer)—where a man, most likely Jonah, is seen inside a large fish or sea monster.

While the back cover of Greenberg’s comic disavows any resemblance to a “real encyclopedia,” the work does suggest a modestly encyclopedic search for influence and connection among the religions and myths of “early earth”; a land of prehistoric imagination. And just as these legends shift in content from tribe to tribe, so too do these tales remain the same yet changed—folded, twisted and mixed into half-recognized forms, like our own imperfect memory of dreams.

In the tradition of works like Apuleius’ The Golden Ass, even our storytellers become intertwined. They are in order of appearance the storyteller from the Land of Nord, the old crone from the land of Britanitarka, and the compositors of the “Bible of Birdman” stored in Migdal Bavel. In this way, our storyteller is no longer firmly planted in a specific time and space but becomes an unlikely traveler traversing borders and tribal specificities, a fabulist who will never return completely to his (or to be more precise, her) homeland or time in history—an ancient global citizen.

While the central narrator of The Encyclopedia of Early Earth is still a man, Greenberg’s tales are invariably told from the perspective of a woman—from the three sisters of the opening story to the ambiguous sexuality of Bird Man-father who also lays eggs to create his children, Kid and Kiddo.

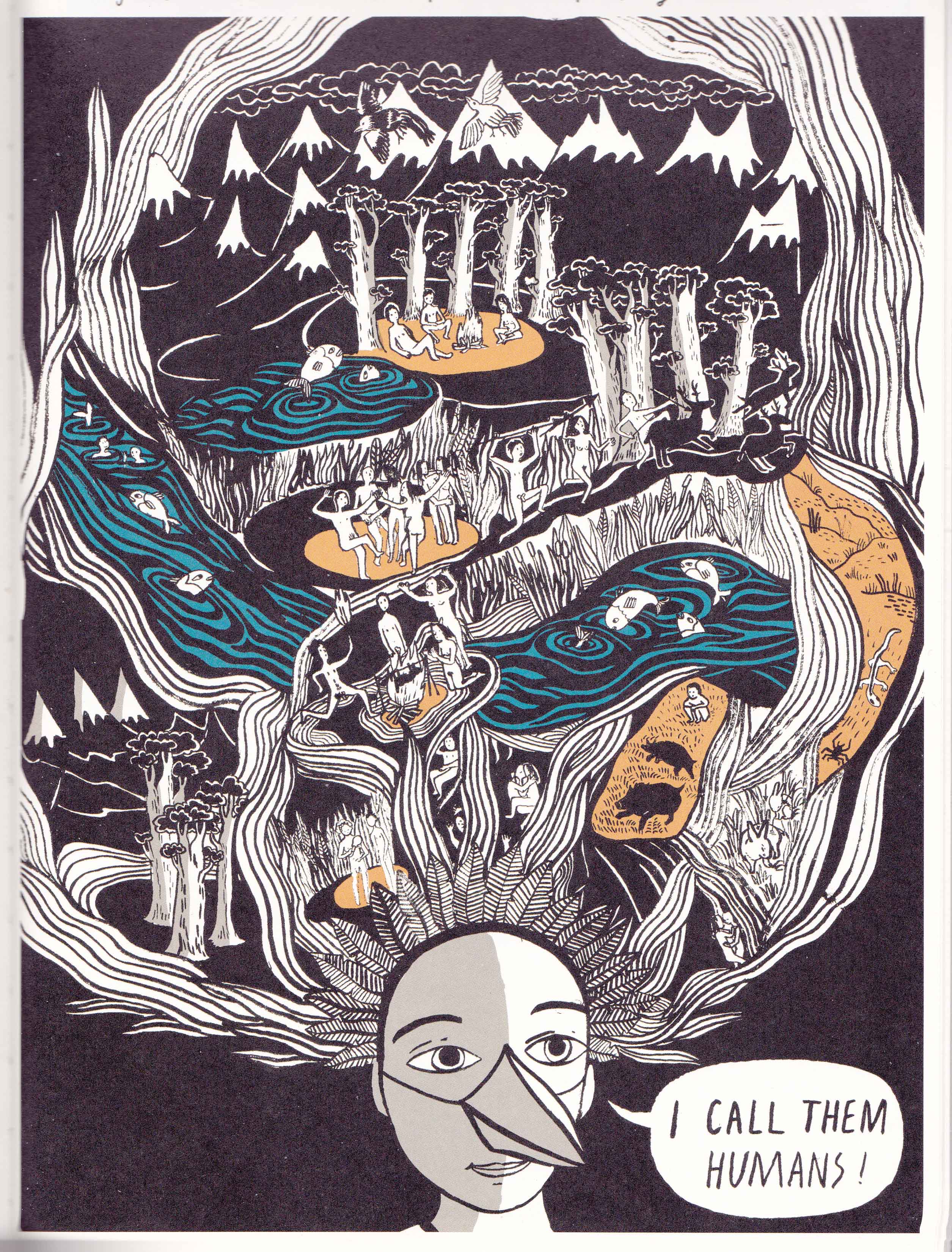

In this pantheon, it is Kiddo the bird man’s daughter who is the creator of the early earth, “a beautiful, complex world of gardens and rivers and mountains and forest…and…tiny little creatures.” At one point, she exhibits a Zeus-like sexual attraction to one of her male creations (cf. Pygmalion and Galatea). This together with her jealousy and rage when she is betrayed (she creates a fearsome deluge) all contribute to this gelding of the familiar legends of old.

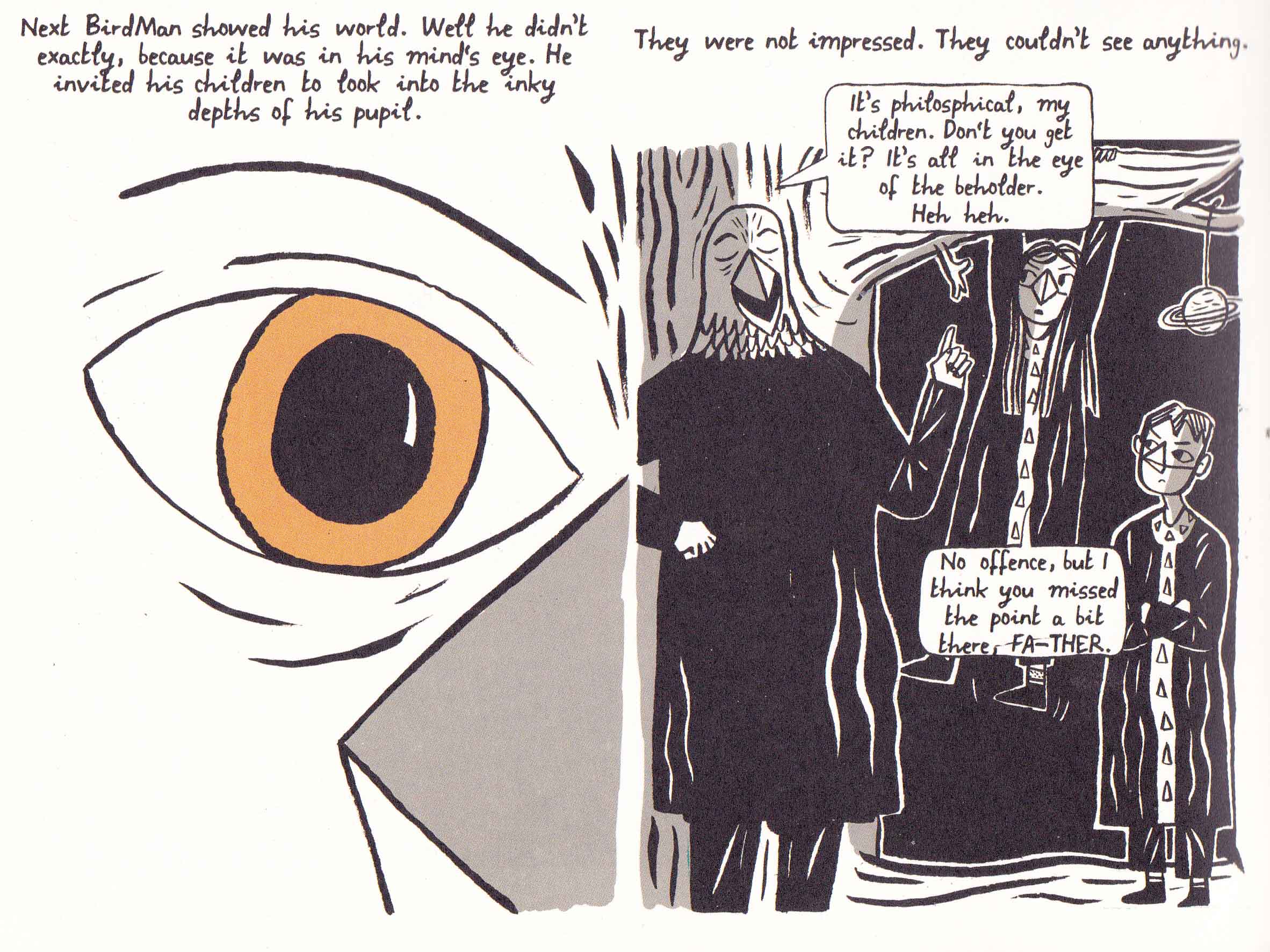

Her father’s conception of the world, in contrast, is purely in his “mind’s eye”—a thought, a mathematical equation, a matter of perspective, the “spirit of science” which is the belief that “the depths of nature can be fathomed and that knowledge can heal all ills. Of this Nietzsche wrote:

“Anyone who recalls the immediate effects produced by this restlessly advancing spirit of science will recognize at once how myth was destroyed by it, and how this destruction drove poetry from its natural, ideal soil, so that it became homeless from that point onwards.”

Kiddo’s creation is a world of matriarchal lineage as evidenced by Greenberg’s opening story where there is a conspicuous absence of fathers (or even male helpmeets) accompanying the three sisters of Summer Island. The ruler of Dag (the land of Nordic appearance) is a female as is her oldest surviving relative and adviser. Our young storyteller who uses his skills to escape the violent and mercurial clutches of the rulers of Britanitarka and Migdal Bavel is at least partly based on that most famous of all legendary storytellers, Scheherazade. As should be clear, he too has had his sex inverted.

Yet it would be a mistake to take the comic as a whole for a subtle but scholarly investigation of the politics and interconnectedness of world mythology. It is far more concerned with poetry than the rational and scientific. Where Joseph Campbell searched for the Ur-myth in the common experiences of primitive man—the trauma of birth, the mother’s breast, the labyrinthine circuit of internal organs, the fascination with excreta, and various other Freudian concepts—this Encyclopedia of Early Earth never devolves into an exercise in studiousness but remains to the end a search for the essential, alluring spirit which guides myth and tragedy.

_______________

Further Reading

Isabel Greenberg in an interview with Paul Gravett.

“My stories are mostly about human relationships really. I think when I was reading and researching folk tales and religious stories, I liked how many of the themes and ideas were universal. Competitive siblings, jealous lovers, childless parents, parentless children, themes like this crop up over and over, because they are fundamentally human. I like stories like that. And I think really I just like stories where Love Conquers All !”

“I looked a little at Scandinavian Folk art, but I am probably more influenced by Medieval Art, Islamic Miniatures, 19th century drawings done by explorers, illuminated manuscripts, antique encyclopaedias and old maps. I research quite widely and am always buying books!”

Interview with Alex Dueben at Comic Book Resources.

“The story within a story structure I took from things like One Thousand and One Nights.”

“I work a lot in black and white and with limited color, mainly because I am actually quite bad at coloring and find it very hard! …In Nord and the South Pole, I used a lot of blues, but I used more wash than block color, to give it an icy, insubstantial feel. In Britanitarka, there are still a lot of blues, but they are more flat color and I put in more grey and flashes of red. In Migdal Bavel, I added some deep oranges and reds and yellow’s in, as I wanted the city to have a different feel to it.”

Pingback: Kibbles ‘n’ Bits 8/26/14: He liked it! Hey Mikey! — The Beat

Pingback: Clickable « DOMINIC UMILE