The index to the Godard roundtable is here.

______________________

Category Archives: Qu’est-ce que c’est Godard’?

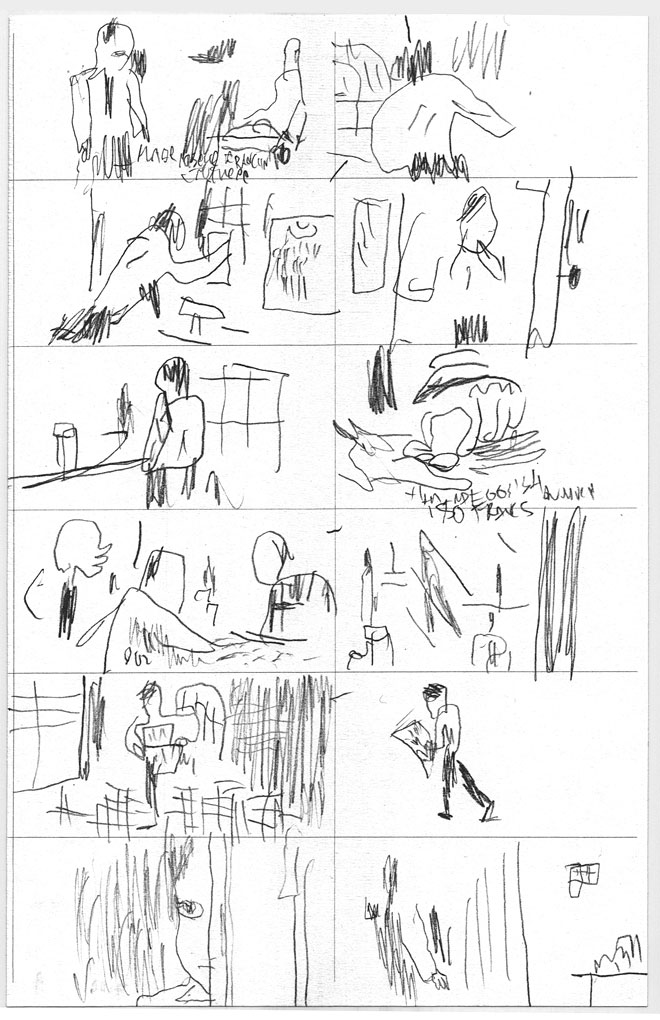

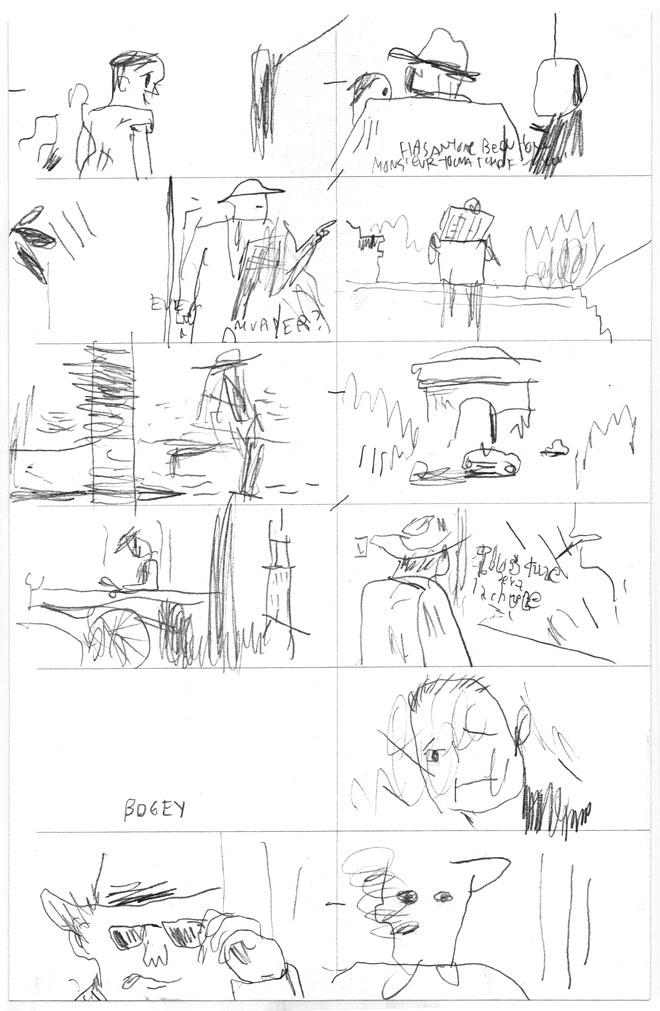

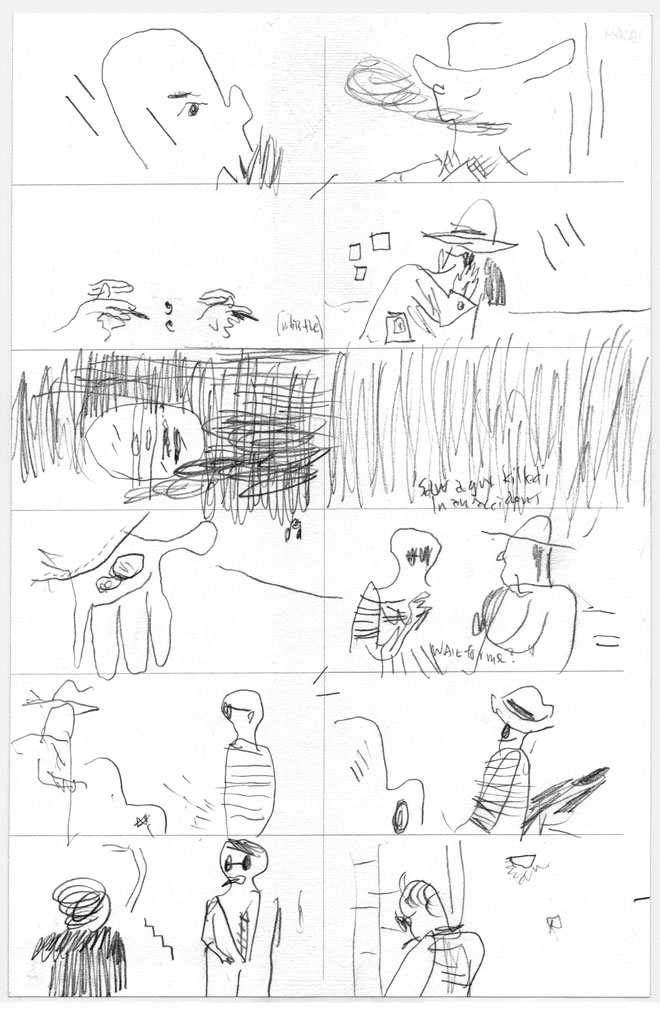

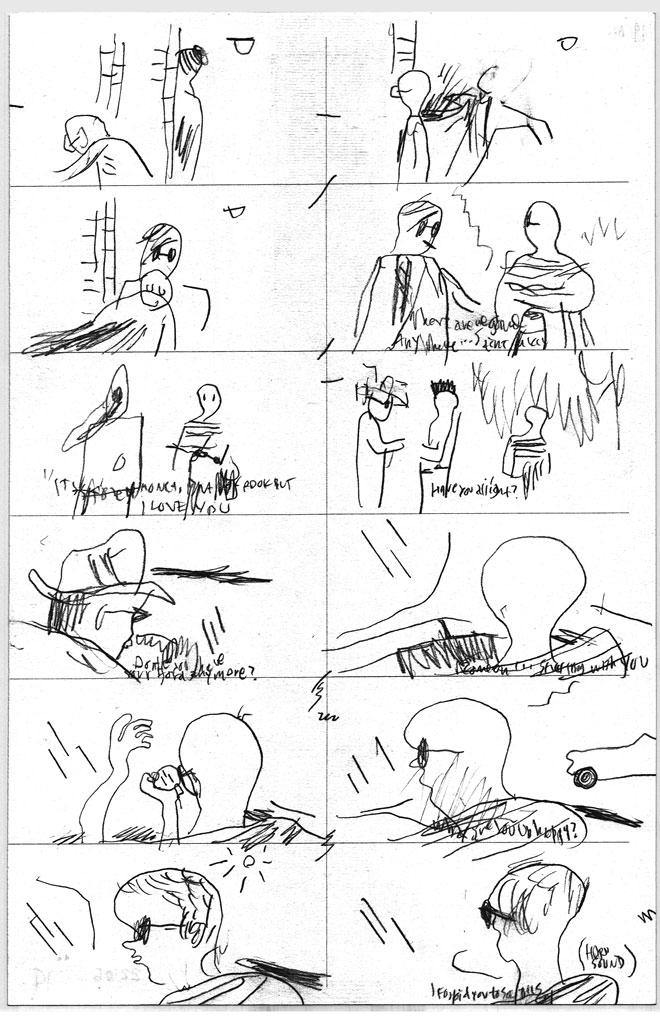

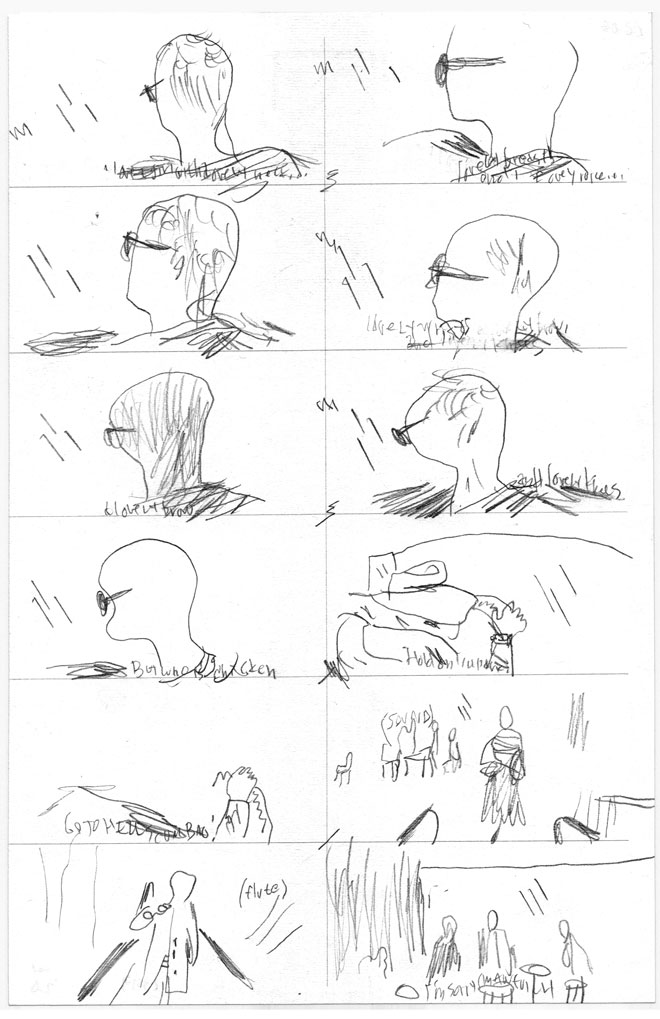

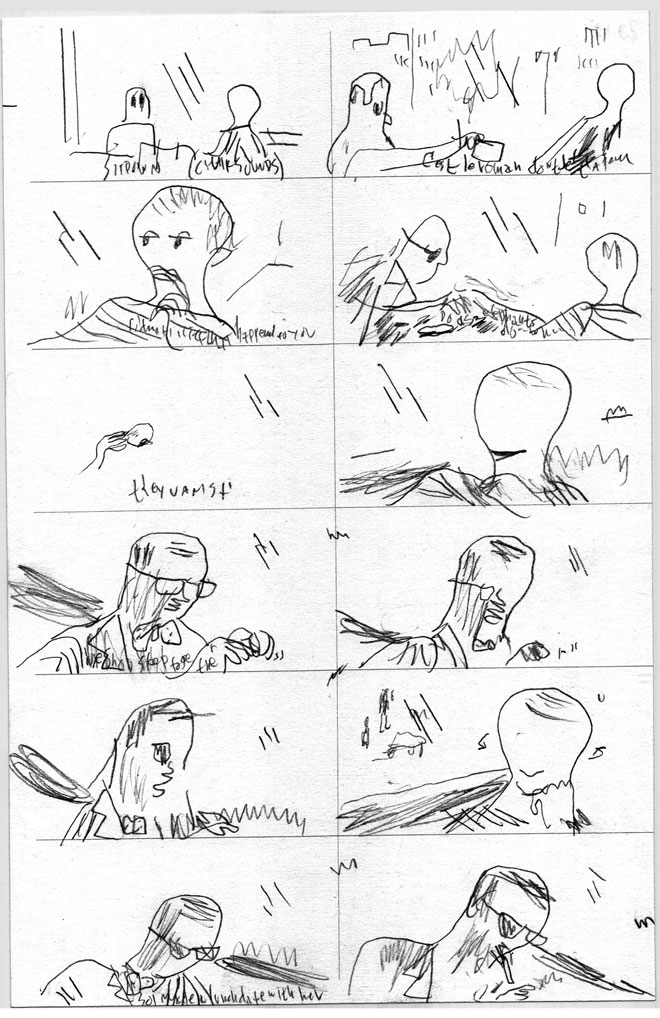

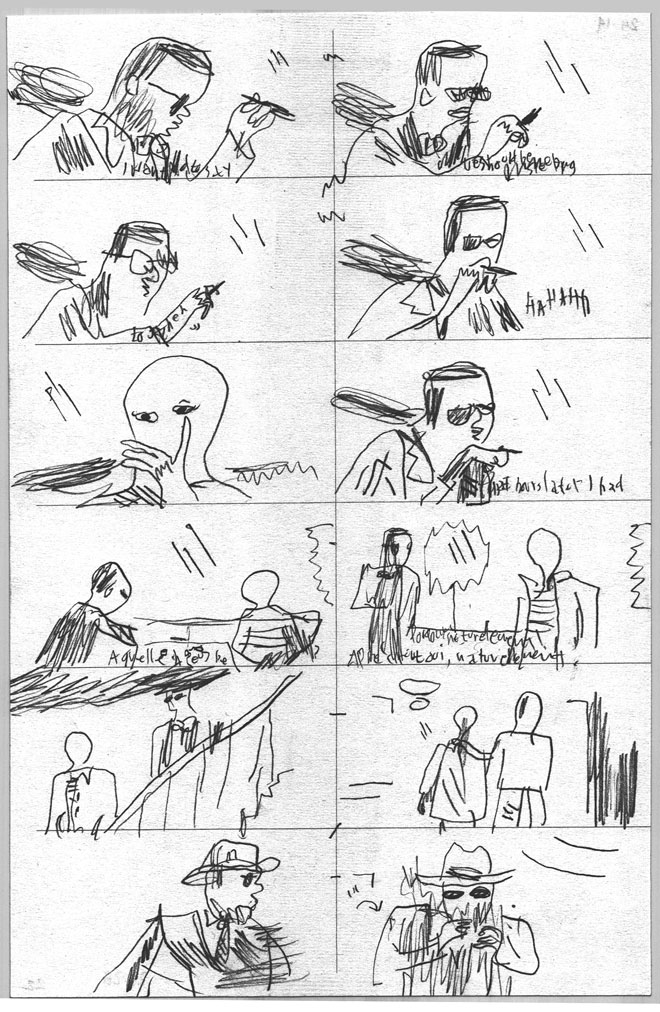

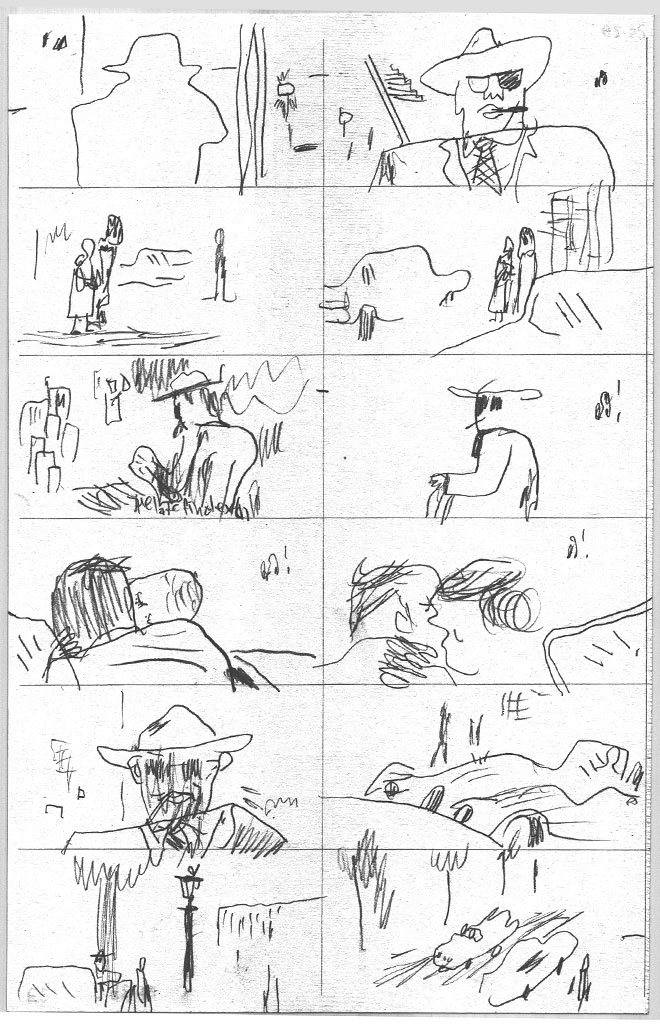

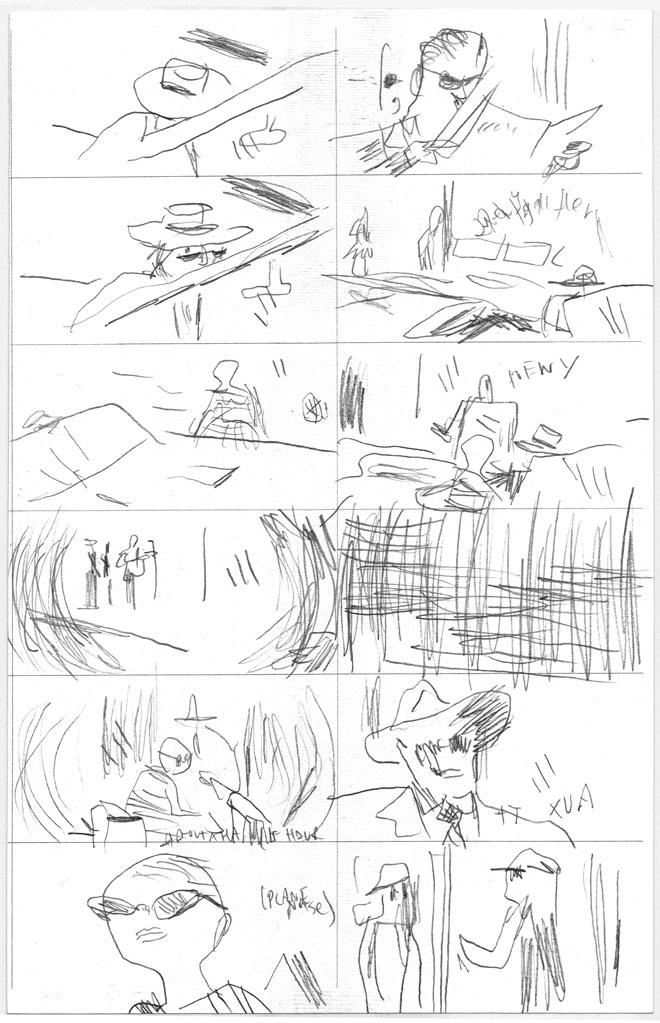

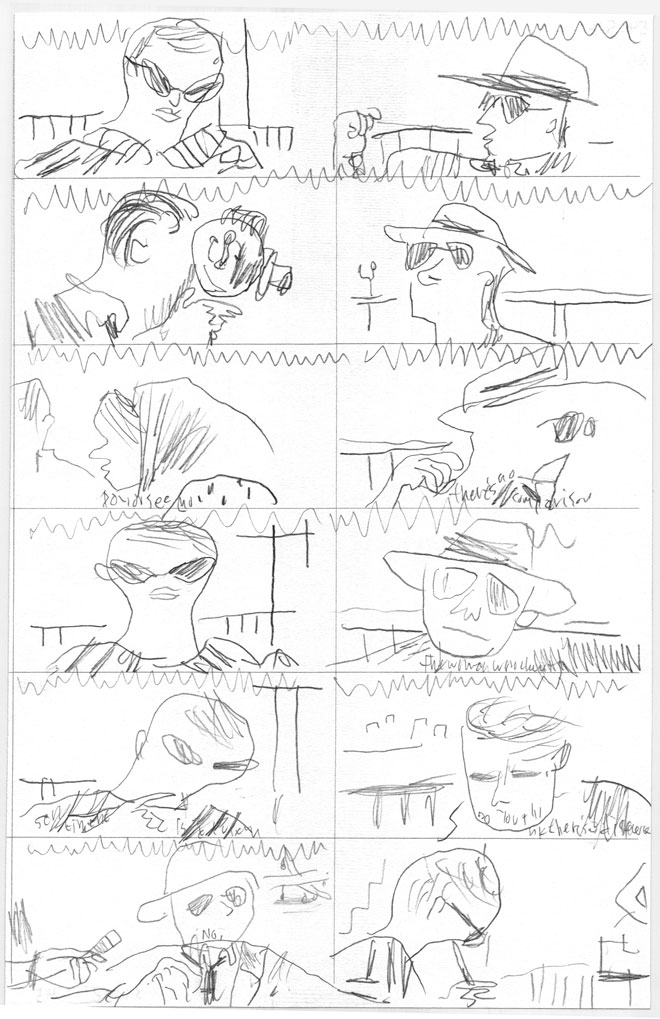

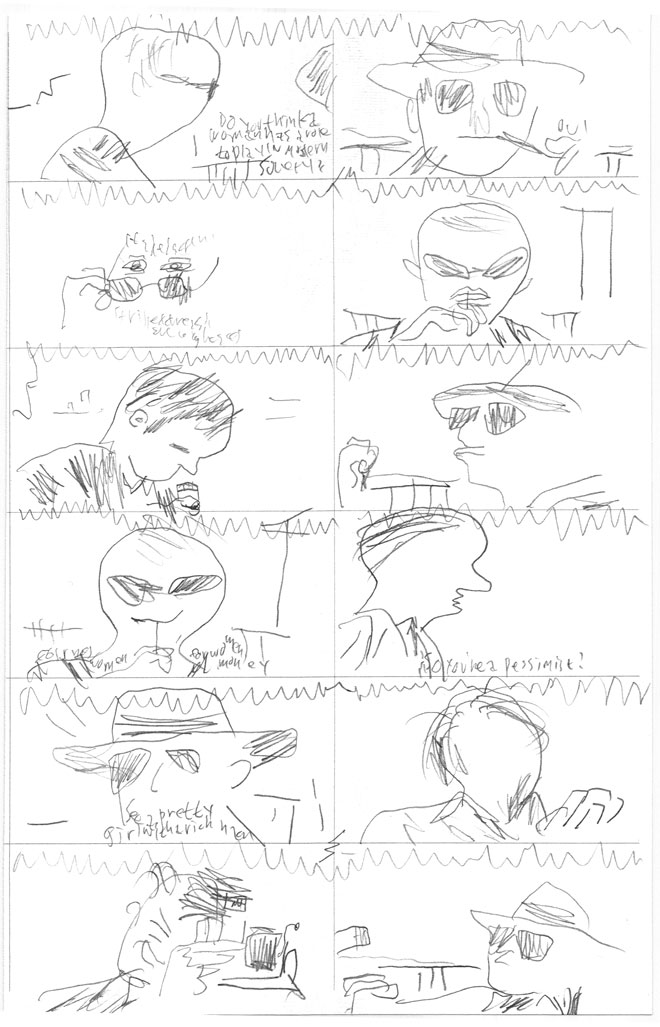

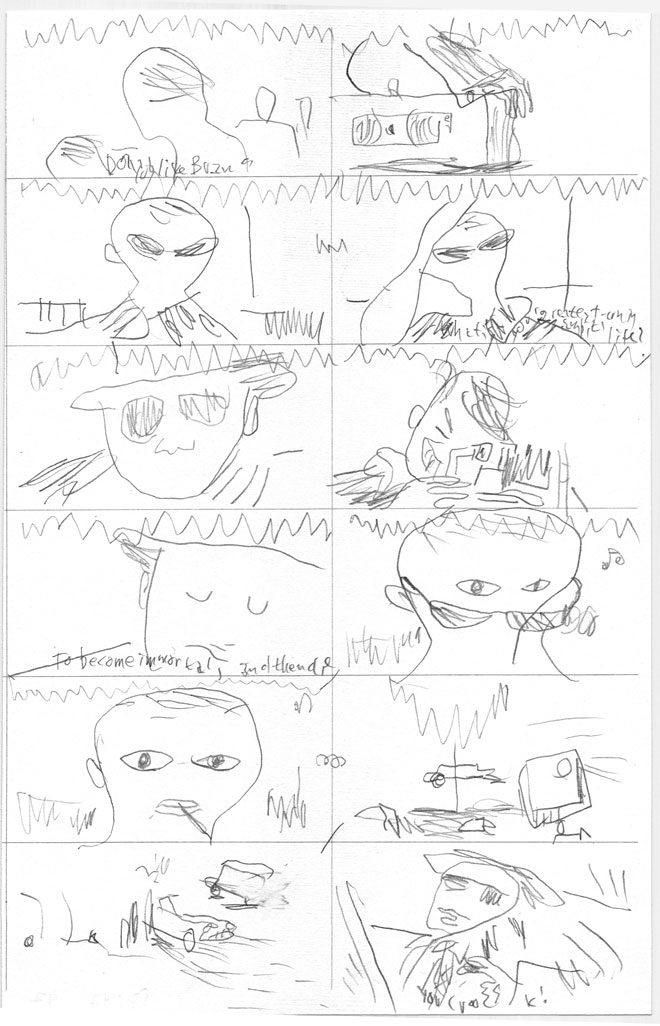

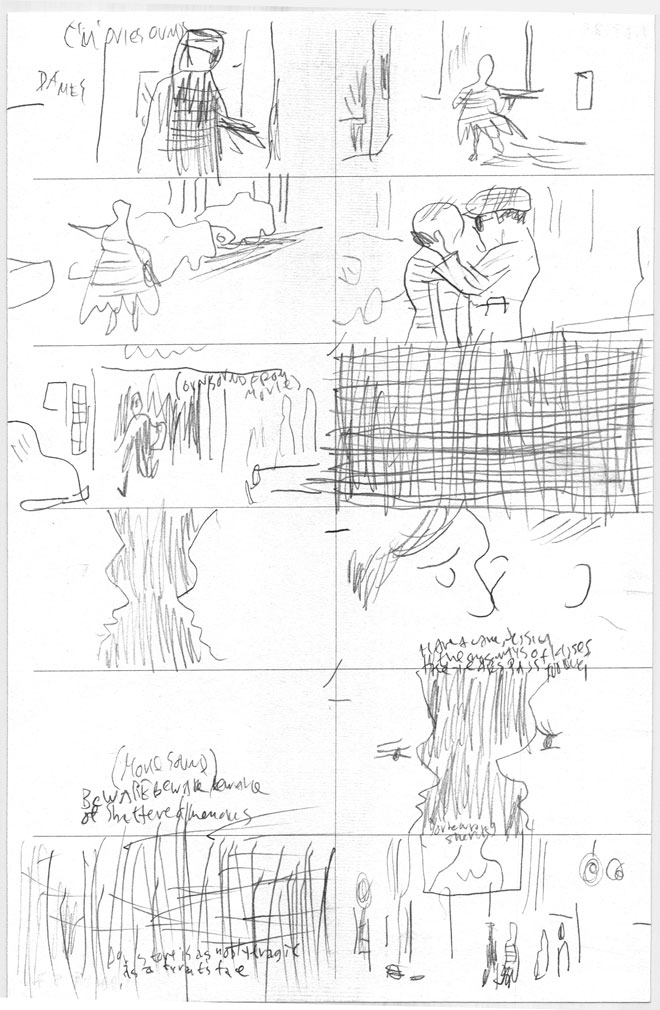

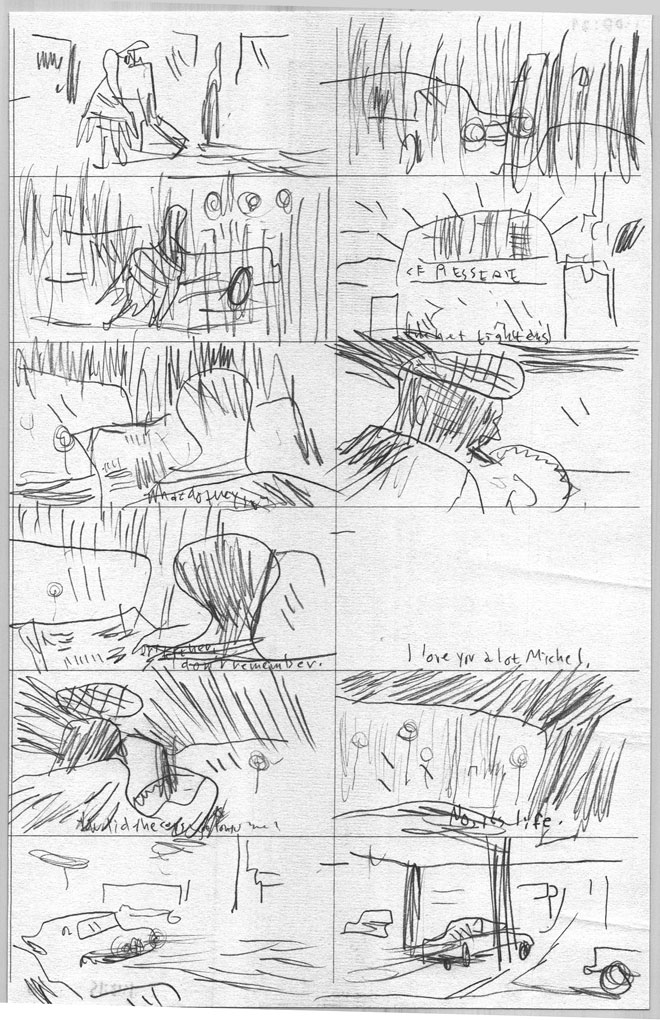

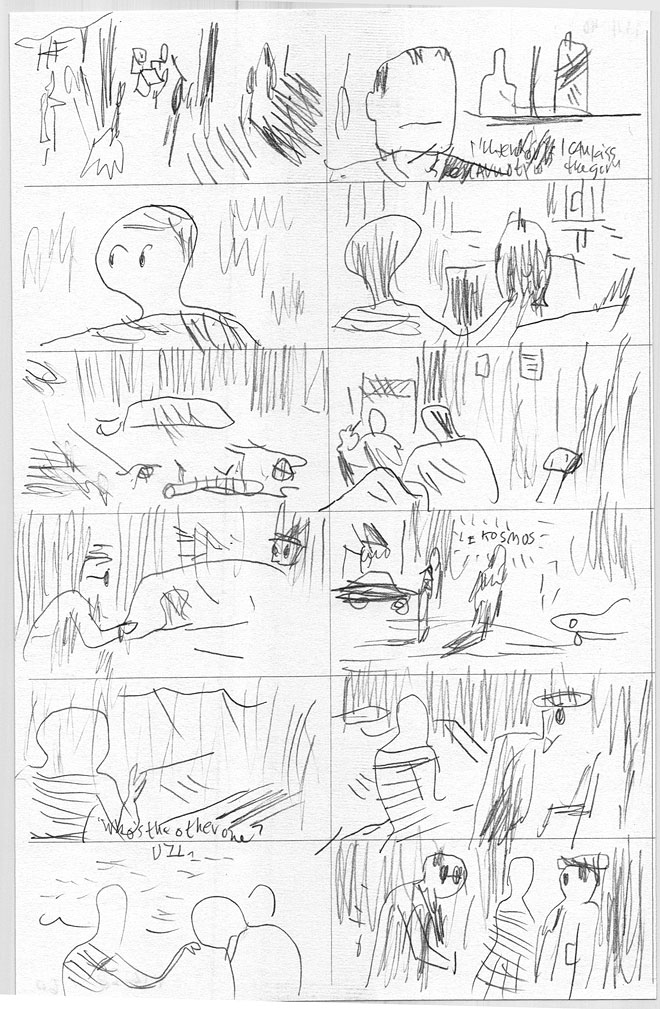

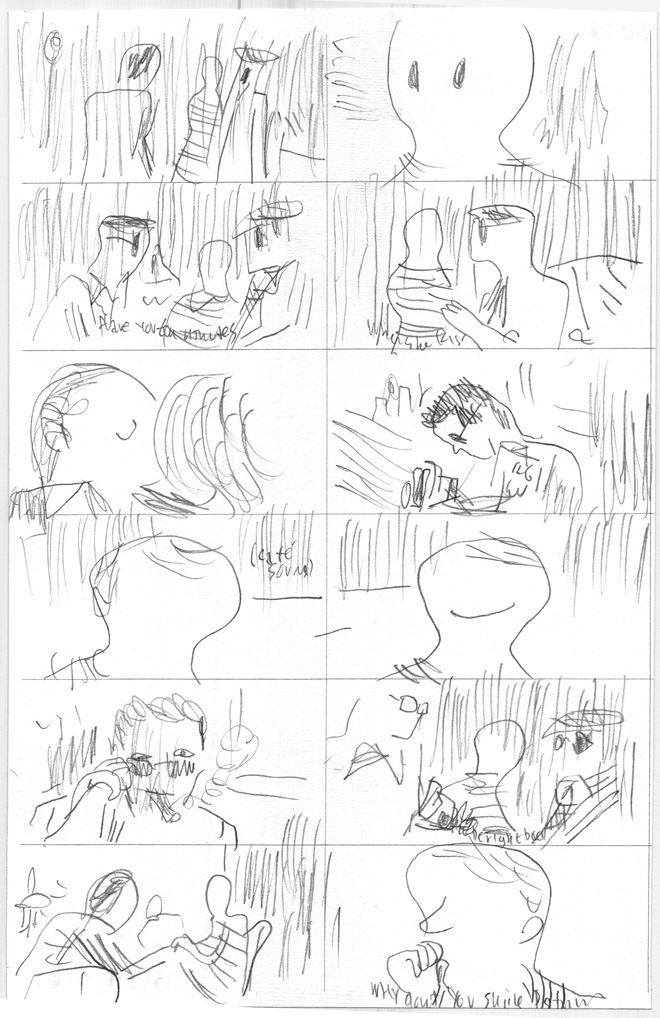

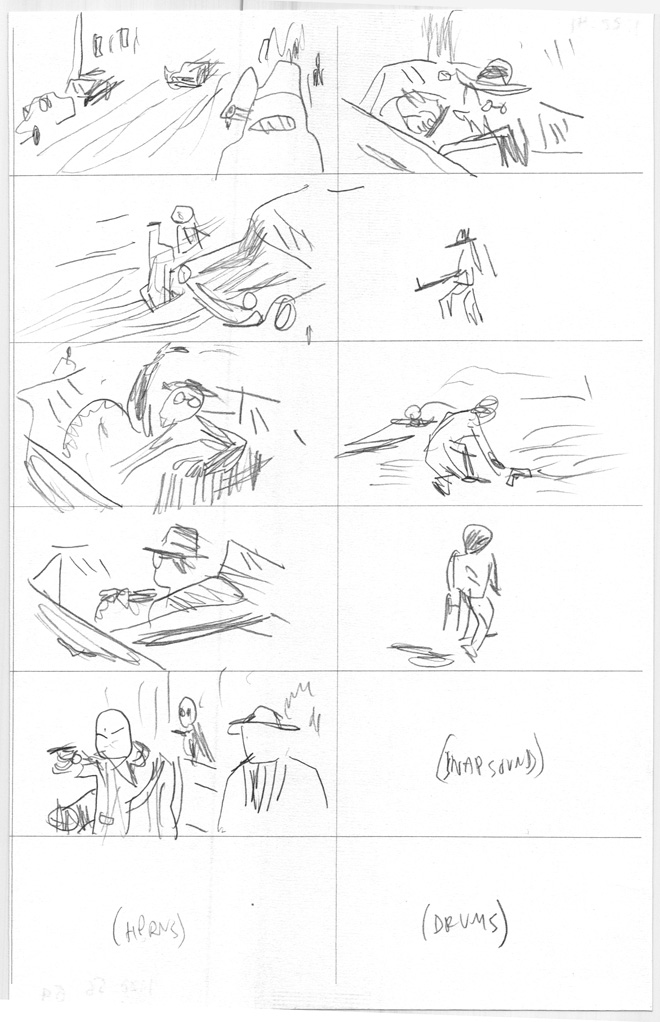

Contempt: A Visual Reading and Other Loose Ends

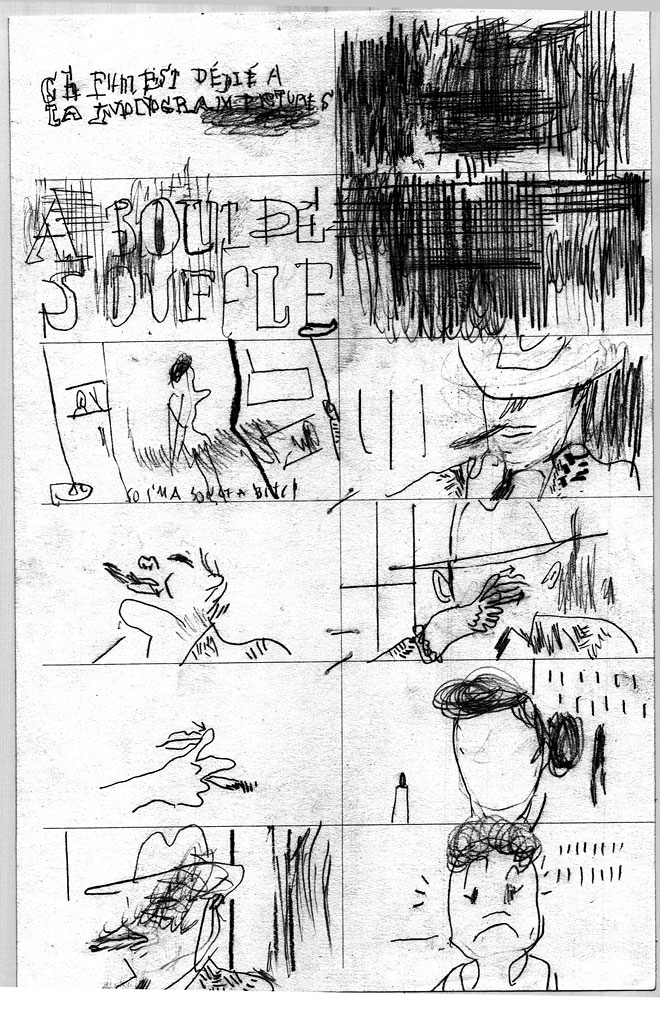

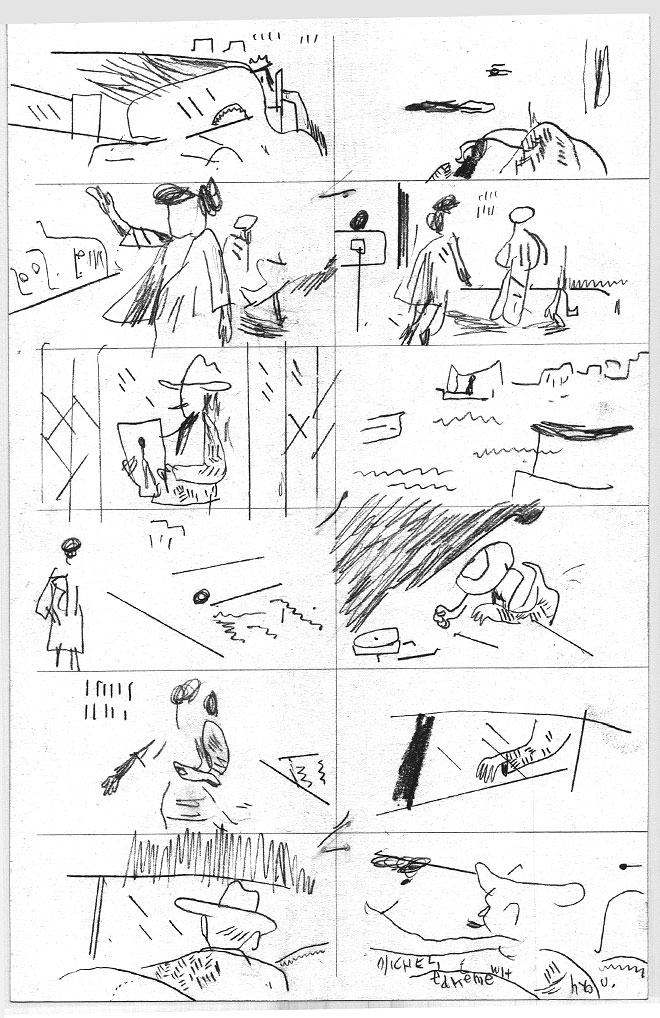

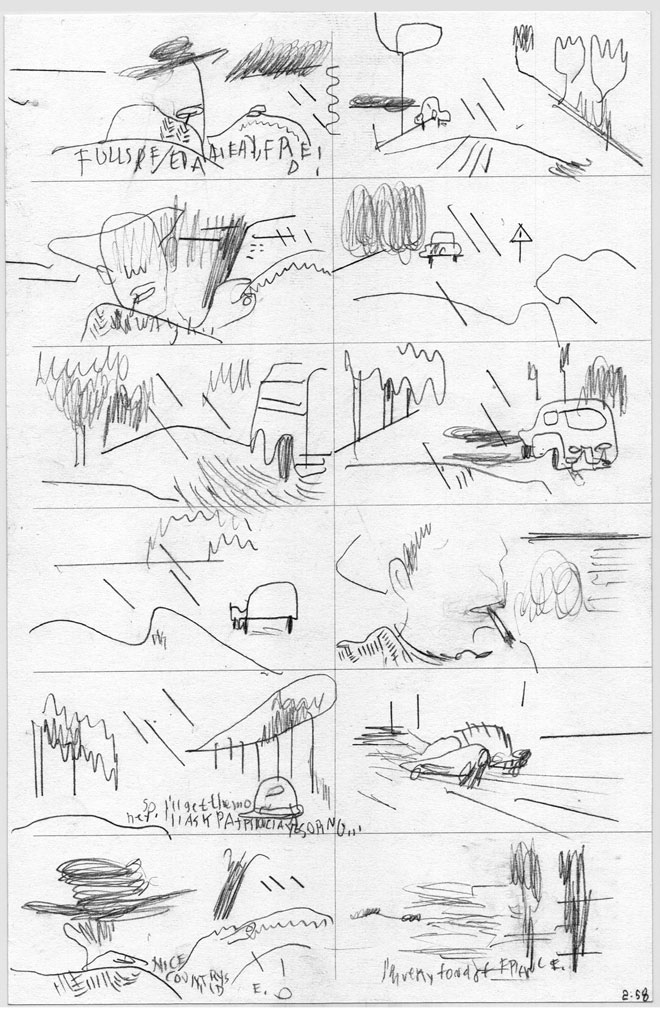

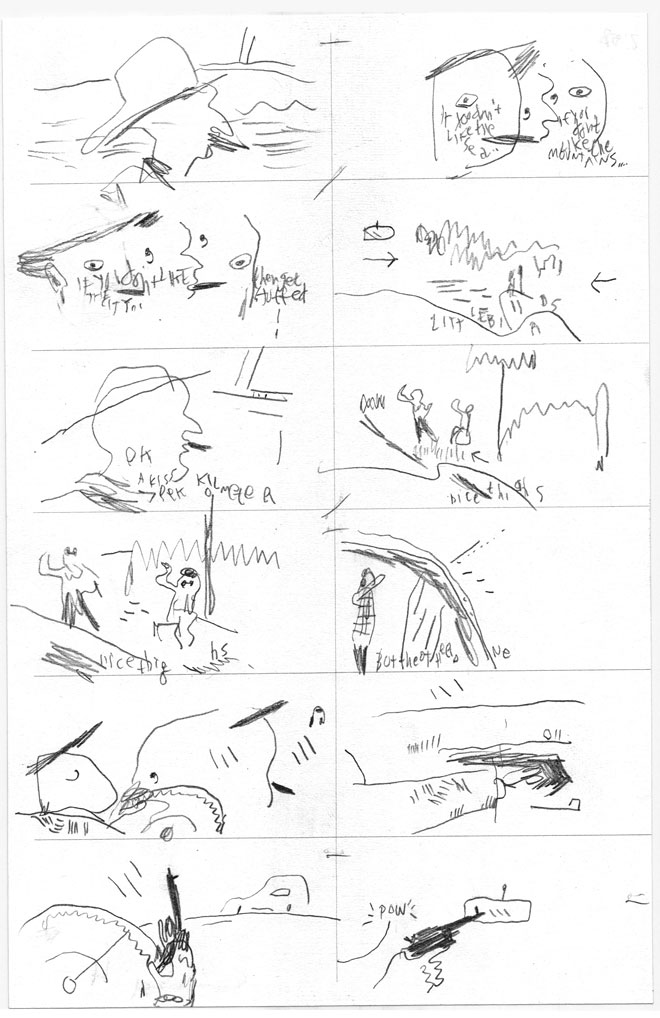

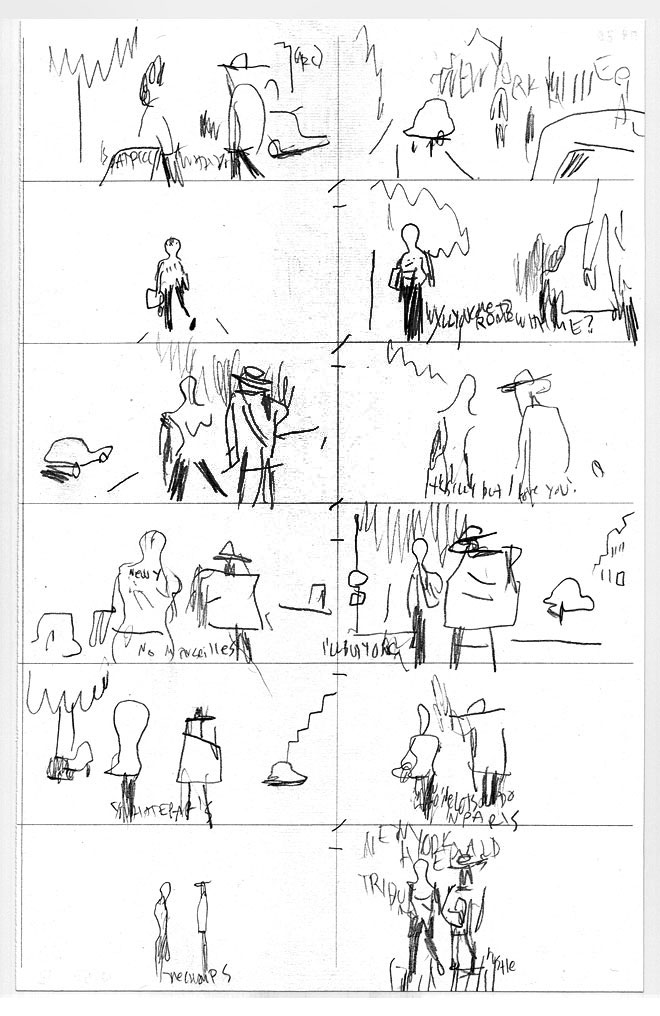

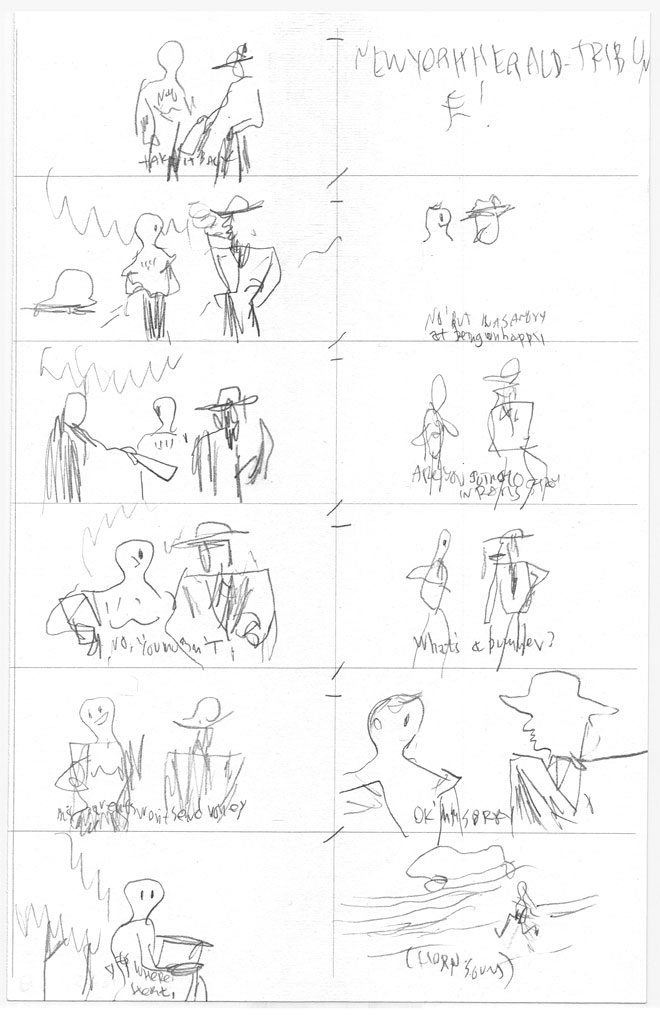

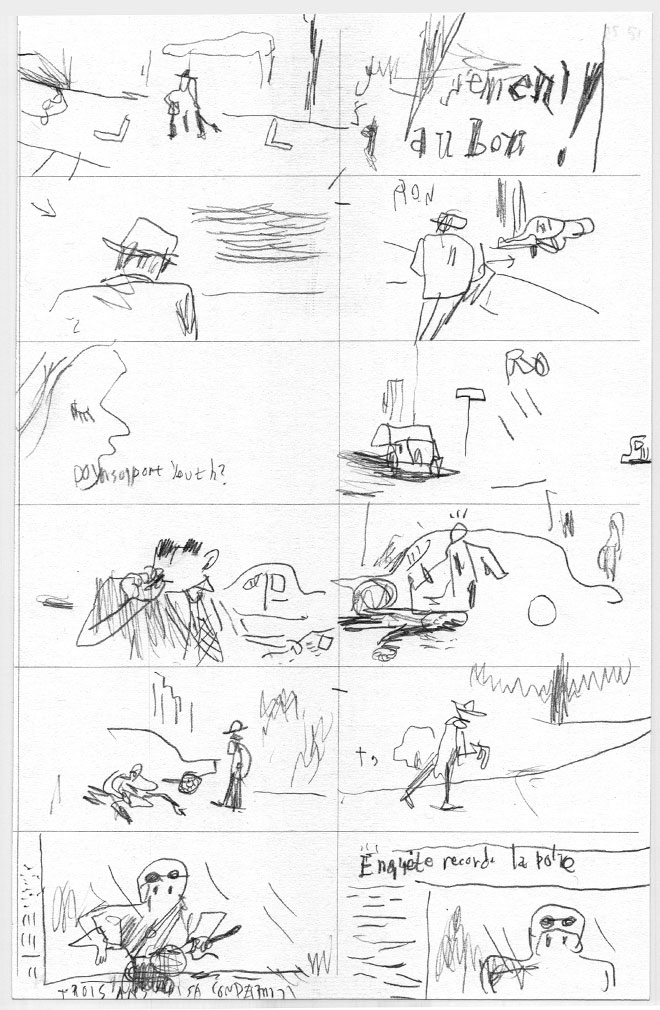

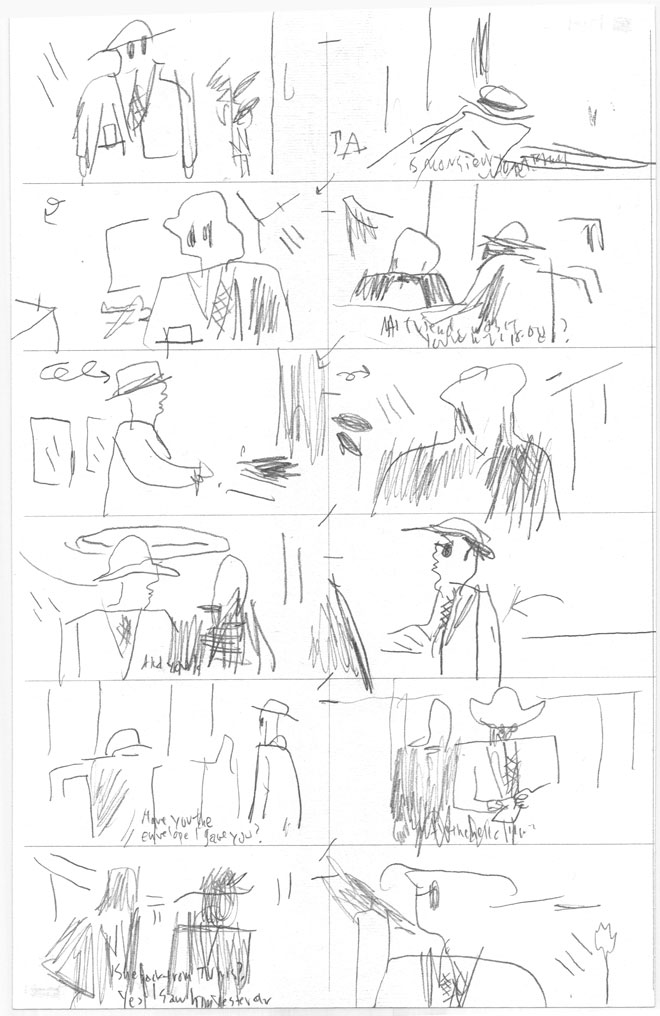

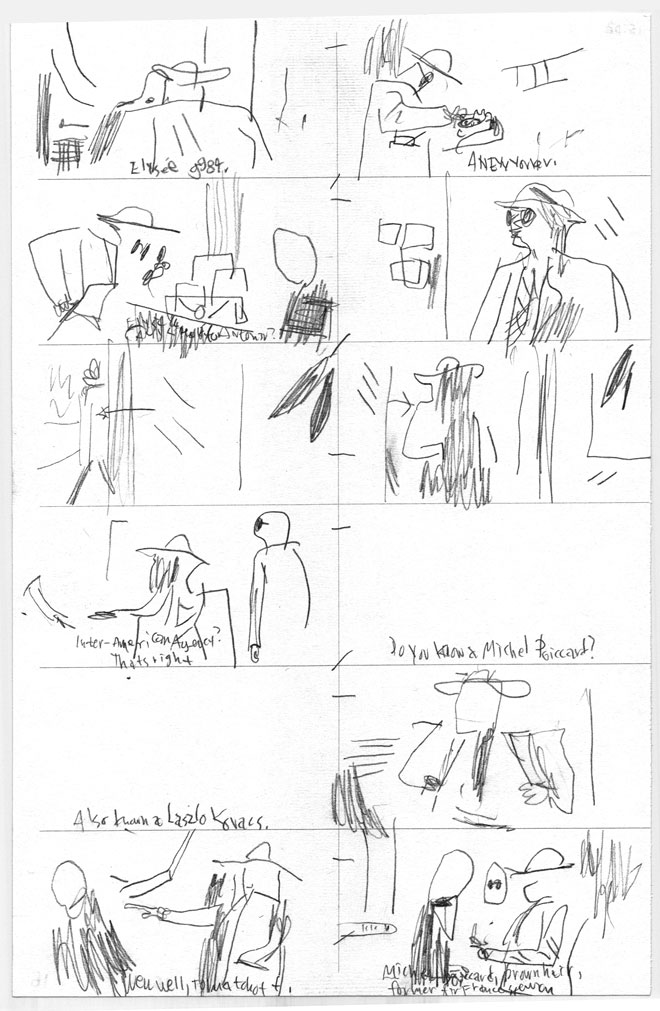

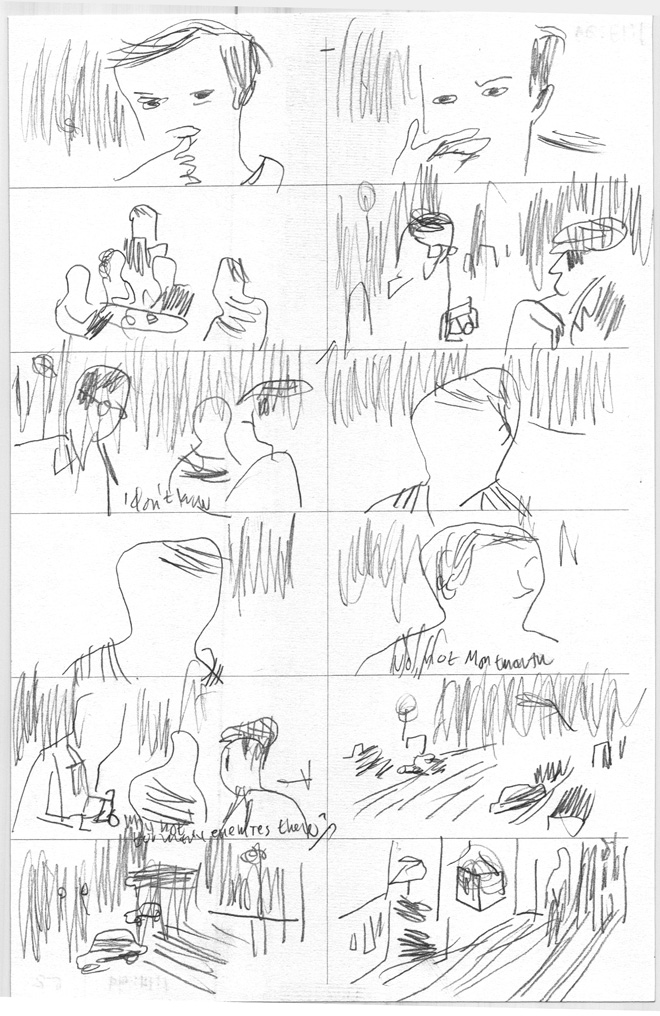

Lucien Goldmann, a Marxist critic, said that Contempt, a film by Jean-Luc Godard (1963): “is about the impossibility of loving in a world where The Odyssey can’t be filmed.” (In a world without gods.) It’s an imaginative interpretation, and a surprisingly reactionary one coming from a Marxist critic commenting on the work of a Marxist director, but it links two of the picture’s themes: 1) the end of the couple Camille (Brigitte Bardot) and Paul Javal (Michel Piccoli); 2) the difficult relation between art and commerce; i. e.: the creative differences between director Fritz Lang (himself) and producer Jeremy Prokosch (Jack Palance). The problem with Goldmann’s thesis is that he reached a totalizing conclusion starting with a particular example, but, mixing gods to the equation, the film invites such an universal statement.

Apparently the reason why Camille starts to despise Paul is more down to earth than hinted above: she feels used by her husband. When Jeremy Prokosch hits on her Paul does nothing until it is too late (he even encourages his advances ignoring her supplicating eyes). Godard himself said that Camille is like a vegetable

“acting […] by instinct, so to speak, a kind of vital instinct like a plant that needs water to continue living.”

Contempt is a tragedy (George Delerue’s score never let’s us forget it; Paul to Camille:

“I love you totally, tenderly, tragically.”)

and that’s why Lucien Goldmann isn’t that wrong. The events are linked together in a fabric weaved by the fates. Paul Javal was a hack who sold his wife the moment he sold himself. Camille doesn’t rationalize her reactions, but she’s a victim of the commodification of human relations.

The gods no longer exist, so, they can’t influence the lives of humans, but, in a capitalist world, money took their place reigning supreme over everything. That’s why Jeremy Prokosch says:

“Oh! Gods! I like gods! I like them very much. I know exactly how they feel.”

To which Fritz Lang replies:

“Jerry, don’t forget: the gods have not created men; men have created gods.”

If men created gods and destroyed them, they can also destroy capitalism.

It wasn’t the first time that Paul was an hack either. He previously wrote Totò Against Hercules. We can only imagine a comedic peplum (Totò, Antonio Gagliardi, was an Italian comedy actor). Contempt’s producer Joseph E. Levine did produce Hercules in 1958 though. He may very well be the target of Godard’s satire. Prokosch is a caricature, obviously: showing him lusting after a nude female swimmer in Fritz Lang’s The Odyssey is a comment on his producer’s insistence to show Brigitte Bardot’s body in the film (Paul:

“cinema is great: we look at women and they wear dresses, they participate in a film, crack, we see their asses.”)

Contempt is full of self-referential and autobiographical details like the one above. Another is Brigitte Bardot wearing a black wig to look like Anna Karina, Godard’s wife. Paul is clearly Godard’s alter ego: wearing a similar hat (as shown in his cameos) and a similar admiration for American films (Camille:

“I prefer you without hat and without cigar.”;

Paul:

“It’s to imitate Dean Martin in Some Came Running.”)

While being on the terrace of villa Malaparte Camille waves at some point. At whom? The paparazzi who infested the surrounding bushes?…

At the beginning of the film, at Cinecittà Studios in Rome (sold by Prokosch to a chain of malls), we can see film posters of Godard’s own Vivre sa Vie (To Live Her Life) and his favorite films also produced in 1962: Hatari by Howard Hawks, Vanina Vanini by Roberto Rossellini; and 1960: Psycho by Alfred Hitchcock. We may draw two conclusions from this list: 1) not everything that money touches is crap; 2) the Italian film industry wasn’t as dead as it seemed because masterpieces continued to be created. This means that the reading of the images gives some nuance to an otherwise seemingly boneheaded message.

Camille being trapped between the posters of a film in which men hunt and a film about a sex worker. It’s no wonder that she wears a dark color. More about that, later…

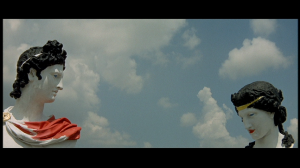

In the above image, taken from Godard’s La Chinoise (1968) we are invited to confront vague ideas with clear images. The image is clear enough to me: it shows a bourgeois interior with red furniture. Red being the symbolic color of communism the contradiction is self-evident, but how many viewers do the reading? In a logocentric culture, what’s shown to us is automatically hidden.

Being a commercial product directed by an avant-garde director means that Contempt self destructs. Godard even mocks the choice of CinemaScope, a format that, in the words of Fritz Lang:

“Is not suitable for Men. It’s suitable for serpents and funerals.”

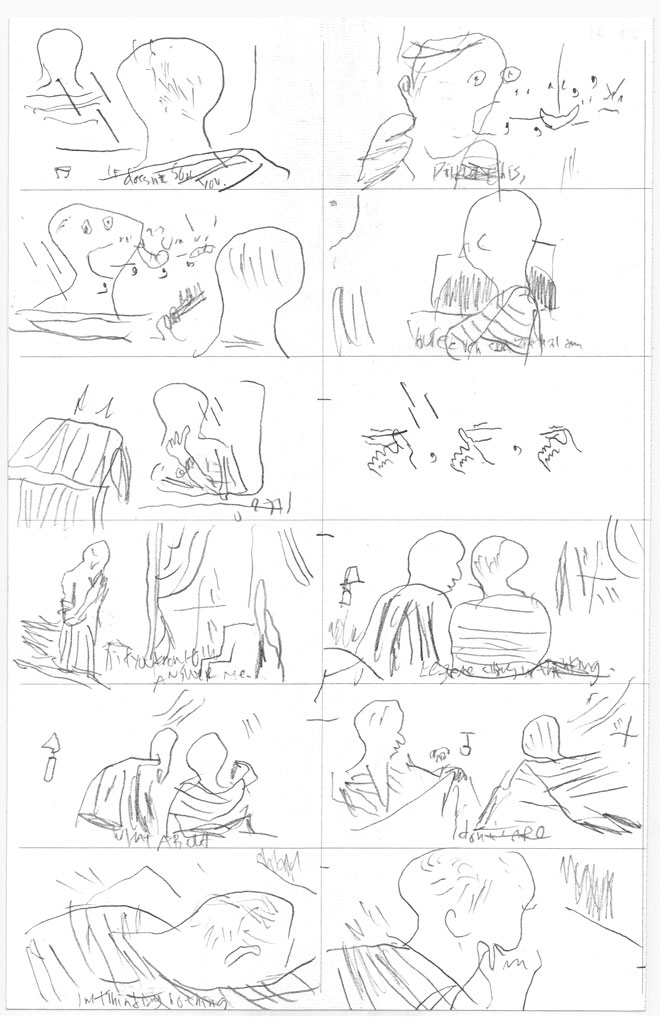

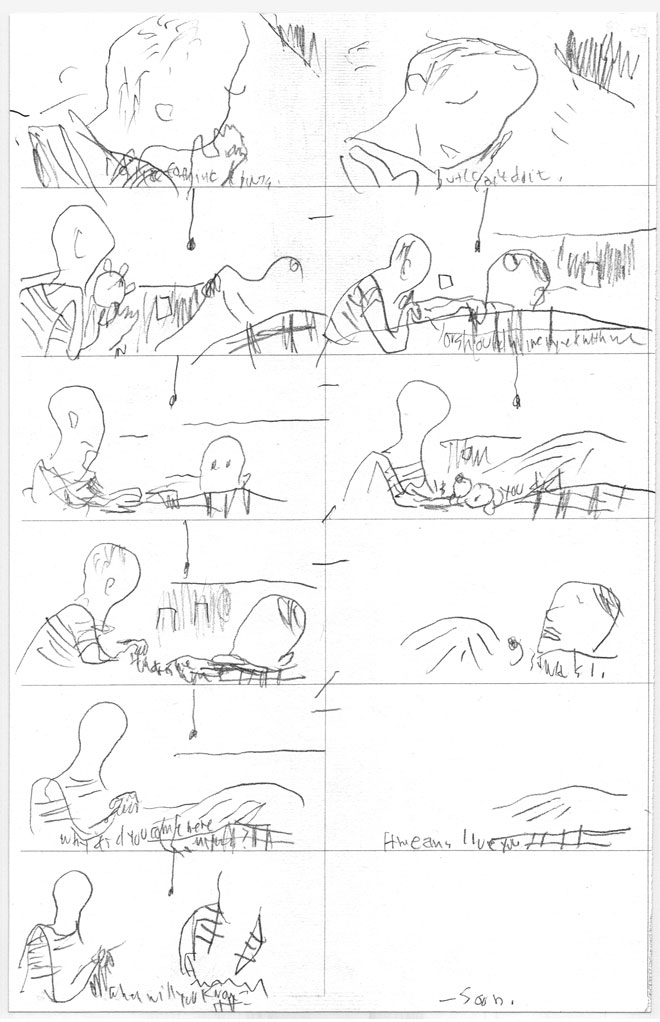

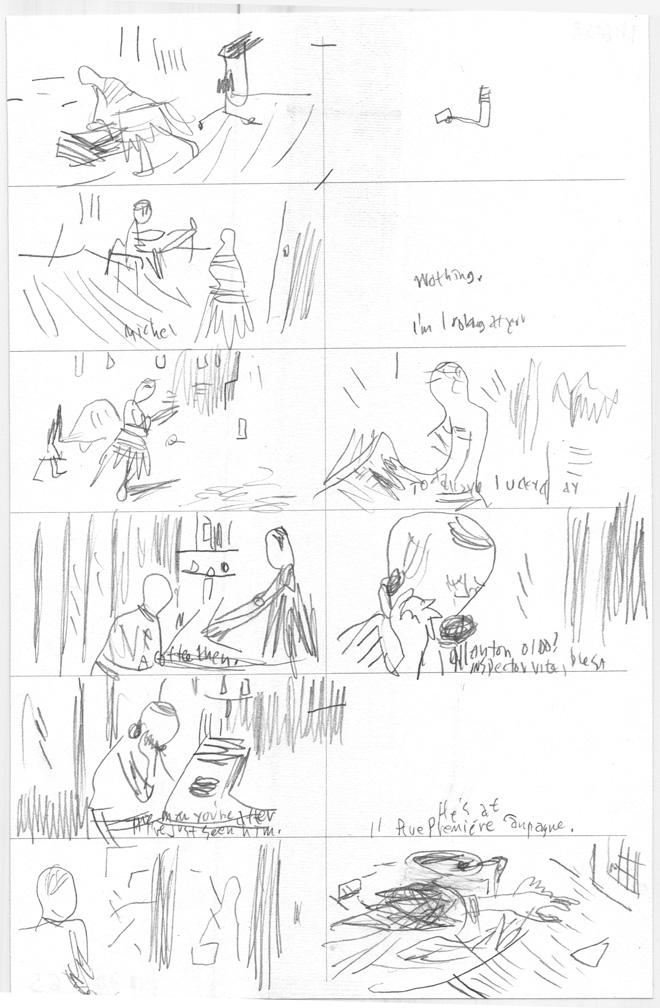

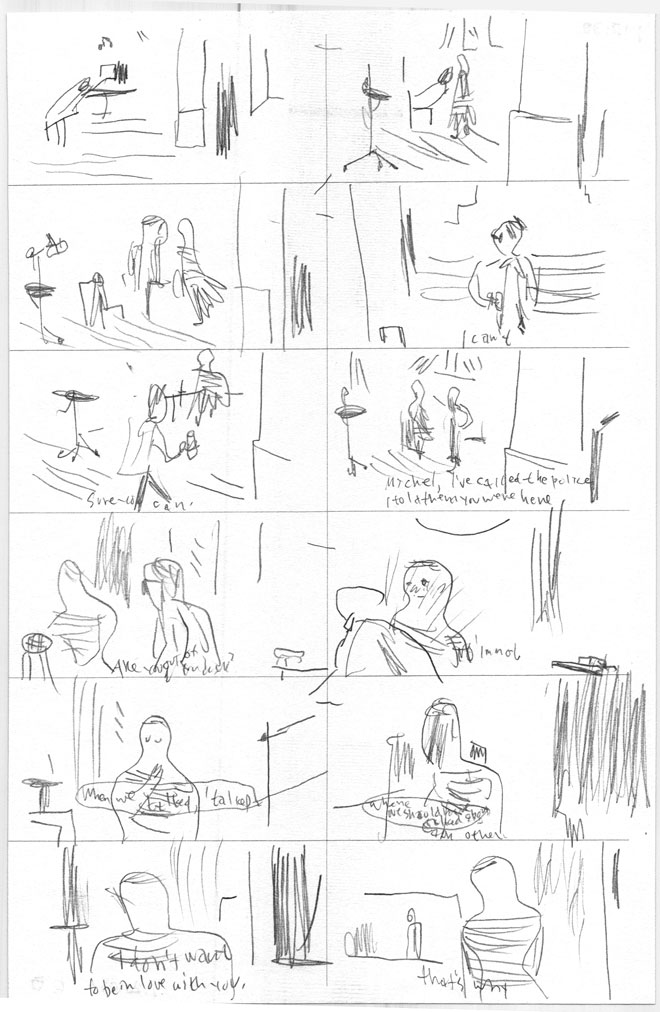

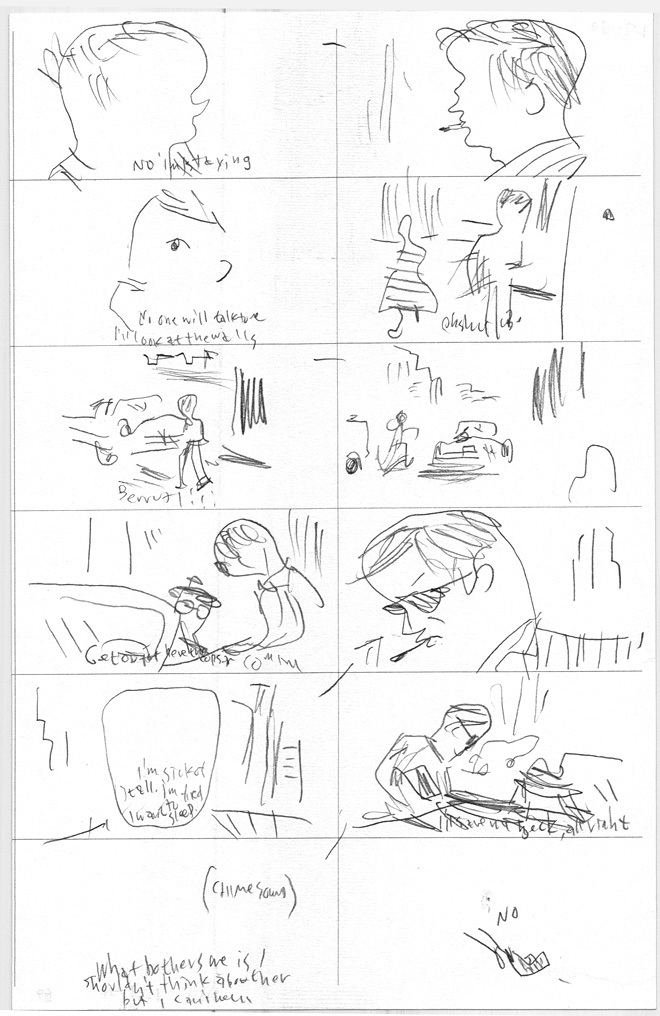

And yet… it allows the most interesting formal device of the film. CinemaScope is the format of epic action movies so something unusual was bound to happen when put in the service of domestic drama. In the central act of this three part play (some may argue that it is the most interesting) Camille and Paul are shown in a maze of walls and doors. (The door without glass that Paul opens to enter a room while returning through the wide opened hole is a Keatonian gag. Ditto Camille absent mindedly passing under a ladder to avoid doing the same on her return when she realized what she had just done.) The couple is shown like mice in a lab experiment, the architectural obstacles between them being symbols of their gradual estrangement. Godard even shows a book about opera and an image of the interior of an opera house to further hint at how ridiculous his producers’ ideas of grandeur are (or as an omen of tragedy). In the duly famous conversation between Camille and Paul with the white lamp between them Godard forces the wide format to behave like a more intimate close up framing refusing to do what would be obvious: to show both actors at the same time.

Another great device used by Godard is color. He uses it (especially the clothes’ colors) as symbols. We know Godard’s attraction for primary colors. In Contempt they’re codified as indifference (yellow, but also green), antagonism, communism (red, but also orange), fate, fight, Neptune (blue). All those colors are shown at the beginning of the film (as filters) to contradict the love scene. Or, in a Deleuzian image-time manner to flash-forward what’s already written in the fates’ tapestry script. The living room in Camille and Paul’s house has blue chairs, a white lamp and an orange couch (it’s almost bleu, blanc, rouge, the French flag; France is viewed as a nation divided). The examples of the use of colors as symbols are too many to cite here: it’s in the orange couch that Camille discovers that Paul is a member of the Italian Communist Party. This turns his selling out to capitalism even more unforgivable of course (being Paul Godard’s alter ego it’s obvious how self-loathing this scene is; ditto Paul using a bath towel to look like a toga in Levine’s peplum). On the other hand the Italian Communist Party was an important member of what was called back then eurocommunism, that is, a revisionist mild version of hardcore communism. We may thus read Paul’s betrayal as a more profoundly political one. Ditto the singer in orange and red at the theater singing a pop song to the masses around her (24000 baci – 24000 Kisses – by Adriano Celentano with the lyrics detourned to include the word “politics”) . In the same sequence Fritz Lang quotes “poor” BB – a pun between Bertolt Brecht’s initials and Brigitte Bardot’s nickname:

“Every day, to earn my daily bread/ I go to the market where lies are bought/ Hopefully/ I take up my place among the sellers. […] Hollywood.”)

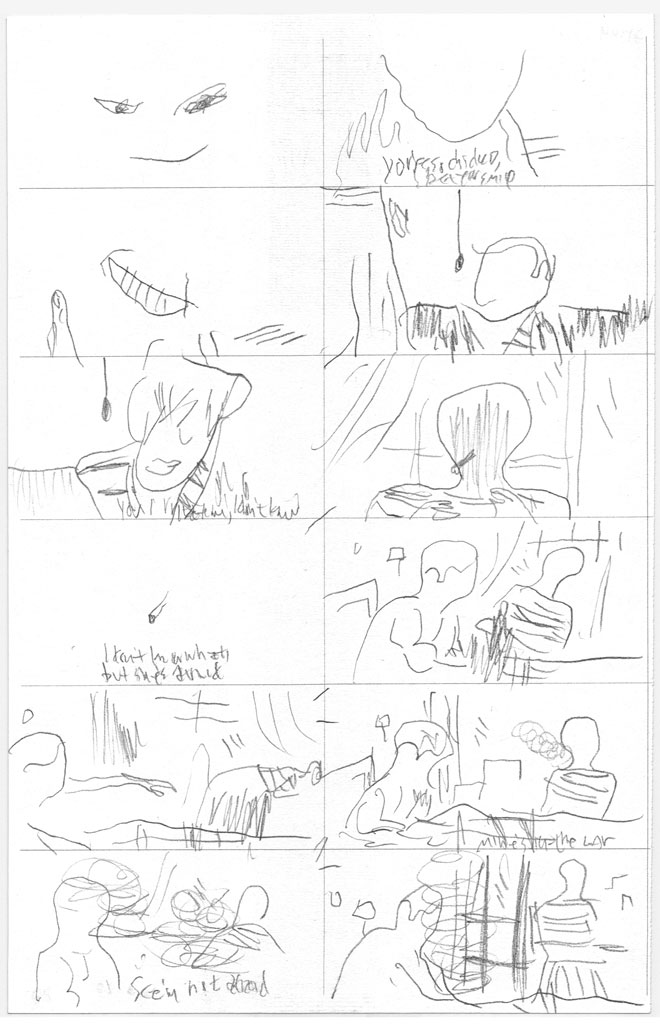

At the end of the film Prokosch’s red Alfa Romeo (Camille:

“get in your Alfa, romeo.”)

has an accident against a blue oil (!) truck. Prokosch, Neptune’s tool, is dressed in red while Camille, a willing sacrificial victim on the altar of capitalism is dressed in blue. (Fritz Lang:

“Death is not the end.”

It isn’t because the film has an epilogue.)

This use of color influenced John Cassavetes in Opening Night (1977). A film about theater as Contempt is about filming. In it actress Myrtle Gordon (Gena Rowlands) fights with a red dress (life and youth) against the forces of aging and decay (black).

Godard, like Johannes Vermeer frames domestic drama to give us the feeling of peeking some secret that we’re not supposed to witness.

Like Rembrandt Godard uses shadow to a dramatic effect: showing melancholia and distress…

The opening shot ends with Raoul Coutartd’s camera pointed at us, the viewers, while a voice over quotes Michel Mourlet (not André Bazin as stated):

“The cinema substitutes for our gaze a world more in accordance with our desires. Contempt is a story of that world.”

What are these desires, then? The camera asks… Do we want tragedy and catharsis like the old Greeks did in their theater? Or do we want unresolved disturbing truths? Godard’s film ends with the death of Camille and Prokosch, victim and tool of an inhuman system. The last sequence being shot in Contempt of the diegetic The Odyssey ends with a victorious Ulysses, as he arrives at his homeland, Ithaca. He is facing the sea (Neptune), to tell him that, against all odds, he fought and beat him. In this story outside a story the

“truth 24 frames per second”

could never do that. (Another cinephile reference in Contempt is Viaggio in Italia – Journey to Italy – 1954 – by Roberto Rossellini, in which a troubled couple finds redemption. The same thing doesn’t happen in Contempt, of course.) The last words belong to Jeremy Prokosch and Francesca Vanini, yes, Vanini (Georgia Moll): after being reminded by Paul that Fritz Lang fled Germany because he didn’t want to have anything to do with the Nazis, the former simply put it:

“This is not 33, it’s 63.”

(There’s no escape.) Plus: Francesca to Paul:

“You aspire to a world like Homer’s, but, unfortunately, that doesn’t exist.”

Betatown

Some shapeless face speaking about robots,

And boredom quivering in the jowls of art

Flop like salmon in the brain cells of the heart.

Oh tragic face of fish, who knows not which was what’s.

In memory a flickering, a future passed like prunes

As detectives loomed and knitted new trench coats.

Grad school will keep you ever young, the careful notes

Ring like leaky bivalves in the analog spittoons.

_________________

The Godard Roundtable index is here.

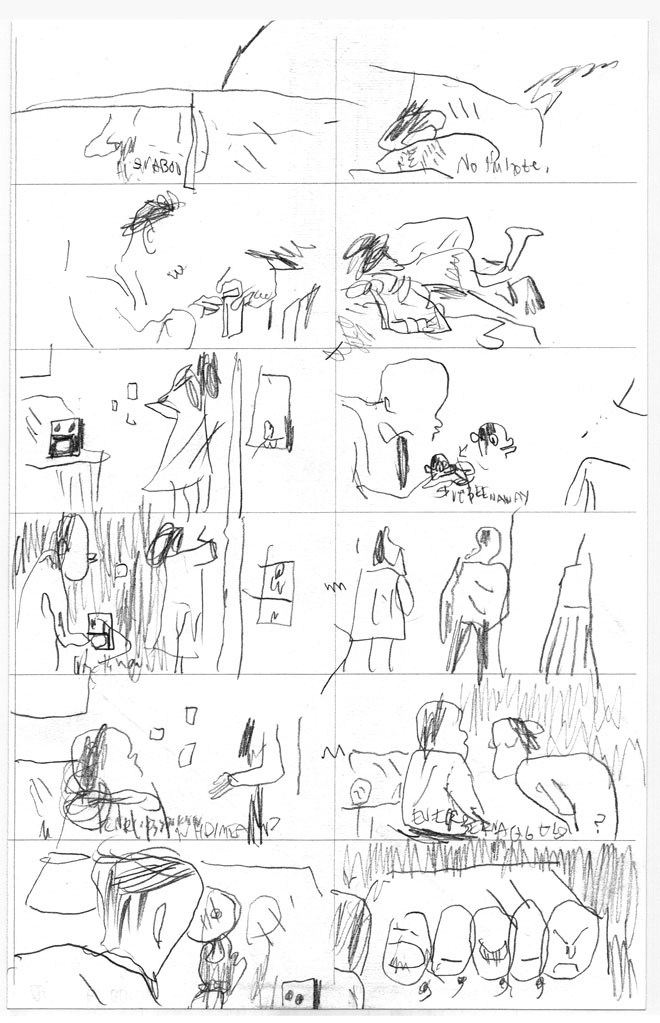

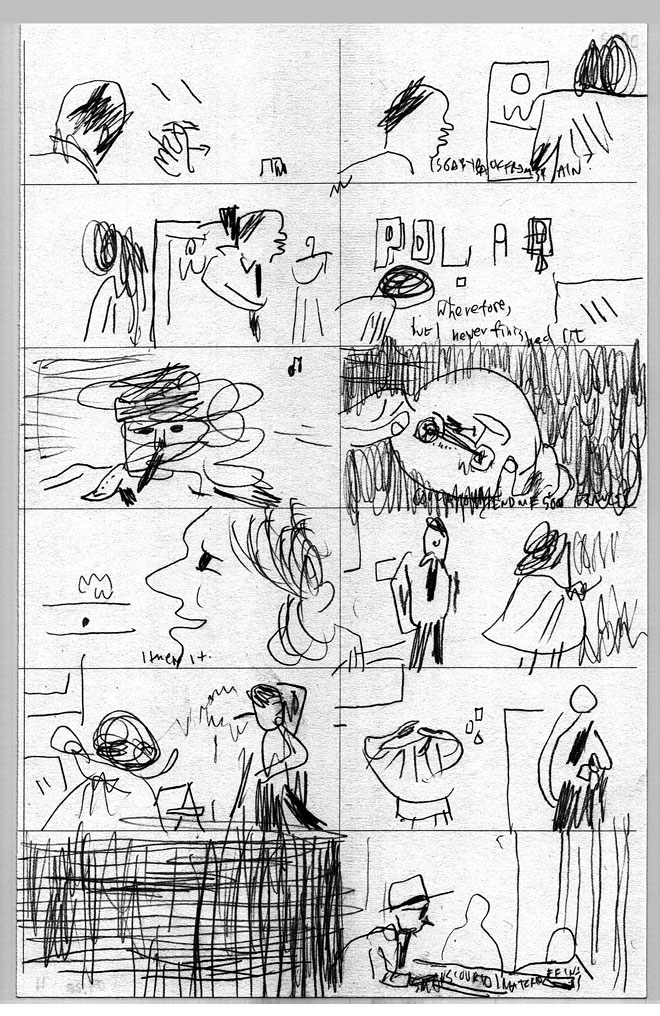

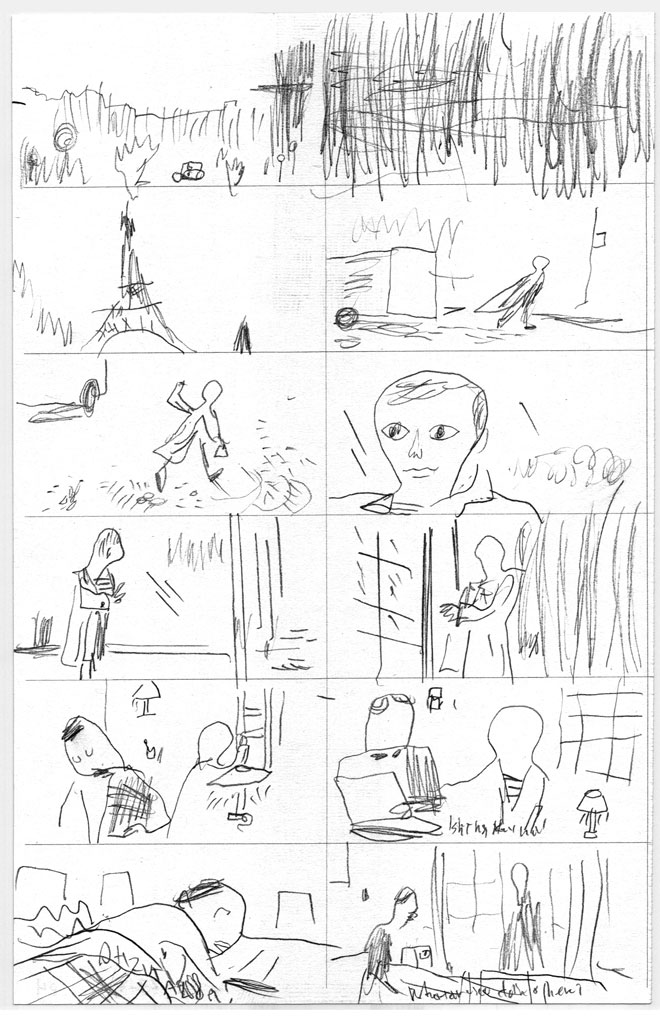

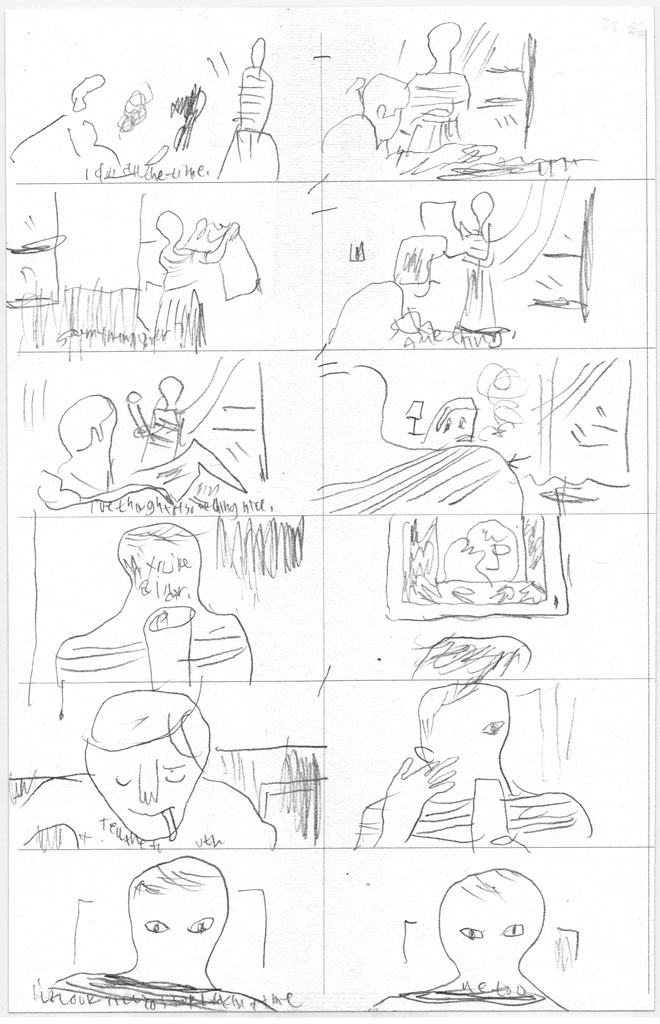

Images of Asses

Contempt opens with a naked Brigitte Bardot asking her beaux Paul (diagetically) and you (extra-narratively) whether you like her butt. Specifically, she asks Paul ((Michel Piccoli) whether he can see various body parts in the (off-screen) mirror, and what he thinks of them. He is (as who wouldn’t be?) appreciative.

The scene is charmingly sexy. It’s also a tease, in more ways than one. Camille (that is, Bardot’s character) doesn’t ask what Paul thinks of her; she asks what he thinks of her image. Of course, we’re looking at the real Camille, not the image — except, of course, of course, we aren’t looking at the real Camille, because there is no real Camille — just an onscreen image of Bardot. The flirtation here, then, is not just Paul playing with Camille, but Godard playing with both of them, and with the idea of image and reality. The scene is less a love letter from a man to a woman than a love letter to the beautiful image of an ass.

The rest of Contempt is almost as self-reflexive as that opening scene. Paul, a theater-writer, is given the opportunity by the crass American producer Jerry (Jack Palance) to rewrite a script about the Odyssey by Fritz Lang (playing himself.) Paul is deeply ambivalent about working on the screenplay; Jerry is a bore, and Lang, who Paul deeply respects, doesn’t want the script changed. In the course of Paul’s vacillations, Jerry casually hits on Camille and Paul himself makes a half-hearted pass at Jerry’s translator/assistant. Somewhere in there, Camille decides she no longer loves Paul. In fact, she despises him.

In a review of the film a few weeks back, Robert Stanley Martin argued that Contempt is about the collapse of communication in a marriage. As Robert says:

Paul is essentially declaring himself a whore, and it’s clear that his seeing it as being for Camille’s benefit leads him to blame her for his situation. He doesn’t stand in the way of the producer’s efforts to come on to her, and he humiliates her further by letting his attention (and hands) wander to the producer’s pretty assistant in her presence. She drops every hint she can that she doesn’t want him to do this job. She even tells him how much happier she was when they didn’t have money and he was hacking out crime novels for a living. But she’s relying on rapport to tell him how she feels; telling him outright means their love isn’t strong enough to do the job. His resentments stand in the way.

That’s a basically naturalistic reading of the film — for it to work, you have to be willing to believe, at least provisionally, that Camille and Paul’s relationship is real. And, at least for me, that wasn’t really possible. A love that could vanish as suddenly and hopelessly as Camille’s love vamished — over the course of a few hours, as both Paul and Camille say — wasn’t really a love to begin with. It was just an image, or a trope.

In fact, Camille’s contempt for Paul seems to be almost entirely a convenient reflection of his contempt for himself. No sooner does Paul accept a check from Jerry than he’s thrusting Camille into a sports car with the oleaginous producer. She’s less a wife than a masochistic fantasy; a dream of defilement. The delirious, endless scene in their apartment — in which the camera shoots the pair passing through doors and hallways or exchanging places in the bath, setting the table and clearing it without eating — has the too-vivid timelessness of a dream. Nothing gets said or understood not because communication between two people has failed, but because that apartment is a skull and there’s only one person in there. Perhaps that one person is Paul; perhaps (as is suggested when Bardot dons a black wig making her resemble the filmmaker’s wife Anna Karina) it’s Godard. But it’s not Camille.

Godard certainly thinks about the way that Camille is a thought. Throughout the film, both Jerry and Paul reimagine the story of the Odyssey in an effort to justify their own view of their relationship with Camille. Jerry speculates early on that Penelope was actually unfaithful to Odysseus; a not-very-subtle wish that Camille will be unfaithful to Paul. Later, Paul imagines that Odysseus stayed away from Ithaca for so long not because he couldn’t get back, but because he had marital troubles and didn’t want to come home. He also grabs a gun and talks briefly about Odysseus murdering Penelope’s suitors, clearly flirting with the idea of killing Jerry.

You could argue that the film is critiquing Jerry and Paul; that it’s undermining or ridiculing their efforts to make Camille their own narrative Pygmalion. Certainly there’s some of that going on; Paul, for example, actually drops that gun without realizing it and someone has to give it back to him — his gangsta dreams are profoundly ridiculous. But, at the same time…Jerry’s dreams do come true; Camille is unfaithful with him. And while Paul doesn’t kill his rival, the film — which is at least somewhat linked to Paul’s consciousness — is happy to do it for him. Jerry and Camille are killed in a gratuitously melodramatic, feebly ironic car crash after they tootle off together, finishing off Paul’s job and his relationship in a single bitterly masochistic ecstasy of revenge.

I was talking about this essay with Caro by email a little bit, and she argued that the unreality of Godard’s characters was not a weakness, but a meta-commentary. “The film is not…about lived reality, but filmed reality,” she said. “So the depiction is of the meaning of the depiction of woman on camera, of man on camera, not about men and women.” Clearly, there’s a lot of truth to that. We’re not supposed to look at Paul, or even at Godard, but at the film of Paul or of Godard. They aren’t asses, but images of asses. You are not meant to identify with them so much as you are meant to contemplate their assness.

But a contemplation of assness is not necessarily, or not only, the same as a critique of assness. Indeed, often, as with Bardot in the opening scene, the contemplation is a pleasure. From its opening shot of a camera on a dolly filming through its sudden interpolations of dramatic shots of statuary to the on-again, off-again dramatically swelling soundtrack to the avuncular presence of Fritz Lang, to that virtuoso dialogue in the apartment, Contempt is boisterously, seductively enamored with its own image. Godard certainly is aware that the woman-as-image, as projection of male sado-masochistic desires and fears, is itself an image. But that image-of-an-image is still irresistibly alluring. Bardot in a wig is a joke about the filmmaker turning Bardot into his wife — but that doesn’t change the fact that he’s turning Bardot into his wife. Camille dead in a convenient car crash is an ironic comment about male ego and filmic wish fulfillment — but the self-referential knowingness just fetishizes the self-reference on top of the wish fulfillment, savoring not the beauty of the dead woman, but the beauty of the reflection of the dead woman. However many lenses you look through, Camille is still a thing in his dream, and contempt is still a pleasure.

_____________

The index to the Godard roundtable is here.

Brecht vs. Godard

We’ve had an interesting discussion of Godard’s relationship to Brecht in comments, and I thought I’d highlight it here.

We’ve had an interesting discussion of Godard’s relationship to Brecht in comments, and I thought I’d highlight it here.

Charles Reece started it off by comparing Brecht to Godard in his post on One Plus One.

As our reality was becoming increasingly mediated by images, where the representation of life was replacing life and human relations were displaced through commodities (compare Pierrot le fou’s famous dinner party scene in which the guests communicate through ad-speak to Guy Debord’s Society of the Spectacle), Godard radicalized his films in Brechtian fashion by subverting cinema’s conventions, calling attention to their mediating effects (albeit Debord and the Situationists weren’t fans): music pops up arbitrarily, dialogue doesn’t sync with the images, quotes (both visual and textual) are used in abundance but frequently have no logical connection to what little plot is involved, etc.

This prompted a series of interesting responses in comments, first by Craig Fischer:

I think you’re the first person to invoke the “B” word in your post–labeling Godard’s films “Brechtian”–and I’d agree that SYMPATHY’s separation of elements, etc. follow the techniques of Epic Theater. Personally, though, I’ve always had trouble with Brechtianism, because (a.) it presumes that the author (or auteur) can create a text that can effectively govern reader/audience reactions, and (b.) it assumes that escapism is a bad thing. What about the counter-argument, made by the great Hollywood director John Sullivan, that escapism is “all some people have? It isn’t much, but it’s better than nothing in this cockeyed caravan…”?

Then Andrei Molotiu responded:

You’re making Brecht’s point for him. Of course, escapism is never “all some people have.” A choice to educate oneself (for example in critical theory, which is only as far as the nearest public library), or to be a creator rather than just a passive consumer, is always possible. But the entertainment industry would like people to believe that is all they have, so as to keep them coming back as obedient consumers. There is a clear connection between corporate interests, the promotion of escapism, and the definition of film as exclusively narrative, fictional and diegetic (therefore providing a story and a place to escape to). From this point of view, “Brechtianism” is exactly the corrective that is needed. Furthermore, if I’m not mistaken, Godard is influenced by Brecht from the very beginning; the jump-cuts in “A Bout de souffle” are already such a verfremdungseffekt, though later they get absorbed fully into narrative filmmaking, forcing Godard to push alienation further and further (especially in “Weekend” and “La Chinoise”–I haven’t gone back to read your review of the latter since reading this comment, but I’m not sure how one can enjoy it without being aware of exactly that intent–I mean, it’s pervasive!)

(I’d also like to point something out here–about how your comment seems to posit “escapism” and “Brechtianism” as the only two choices… But discussing that would take forever. Let’s just say I see it at least as a sliding scale, with many hybrid possibilities in the center, and also other approaches–Brakhage, say–that do not fit on the scale at all, though a Brechtian approach certainly could prime viewers for them.)

Your other “trouble with Brechtianism” is that “it presumes that the author (or auteur) can create a text that can effectively govern reader/audience reactions.” But isn’t that exactly what Hollywood does–indeed, isn’t that Godard’s main problem with the Hollywood institutional style? It’s just that Hollywood does this through emotional manipulation, counting on an (ideal) ideologically-blinded viewer, while Brecht (and again, I haven’t read him in decades, so I’m working from memory now) undertakes to educate the audience as to its own risk of being manipulated, and then refuses to manipulate it emotionally (for example, through catharsis, which, IIRC, was one of Brecht’s bugaboos), rather trying to educate it and therefore (hopefully) to help it judge rationally the presented ideas and narrative?

Well, that’s the theory, at least. In practice, as shown by Godard, verfremdungseffekts can clearly be used without a single-minded didactical purpose, can be used more “modernistically,” I guess you could put it, but, nevertheless, the Godard/Brecht notion involves a more aware cultural consumer, one who is conscious of the possibility of his or her own ideological manipulation–a much more positive scenario, I’d say, than the ideal consumer of Hollywood spectacle that Sullivan’s comment implies.

And then Craig again:

My mistrust of Brechtianism stems from Brecht’s assumption that much of the misery in life is a product of capitalist ideology. Brecht, like Marx, is at heart a utopian; if we offer the masses an alternative to mindless escapism, Brecht says, they can take steps towards liberation. The problem with this, however, is that sometimes life can be brutal in ways that have little to do with ideology. People die and shit happens regardless of the nature of the social order, and during those times escapism can be a balm. The examples that come to me are personal ones—how after my mother’s death I re-read old comics to escape into a nostalgic haze for a while—but I do think that SULLIVAN’S TRAVELS is a credible rebuttal to Brecht. Sometimes life sucks, and escapism helps.

In some ways, we’re on the same wavelength here: we both lament the overwhelming dominance of Hollywood escapism, and you’re right when you say that Brechtian aesthetics are a corrective. Given that Hollywood operates within a pathetically narrow narrative field, other types of films—Brakhage’s closed-eye abstractions, Bergman’s psychodramas, Antonioni’s languorous ennui, etc.—function as radical alternatives. I’d also agree that it’s a sliding scale between the extremes of Hollywood storytelling and Brechtianism, a point that Brecht himself acknowledges when he categorized his own plays into “culinary” Epic Theater (with enough old dramatic tropes to give pleasure to a mainstream audience) and Lehrstucke (much more experimental, and designed for already enlightened participants).

I’d disagree, though, that the Godard of BREATHLESS was Brechtian. The jump cuts and formal play in his earliest movies jolt the audience, but many of the pre-1965 Godard films don’t follow that jolt with any political content or point-of-view. There are plenty of exceptions—the Algerian War in LE PETIT SOLDAT, or the critique of consumer culture in A MARRIED WOMAN—but movies like BREATHLESS, A WOMAN IS A WOMAN and BANDE A PART give us Brechtian form but virtually no radical content. In his book A CERTAIN TENDENCY OF THE AMERICAN CINEMA, Robert Ray points out that plenty of late 1960s-early 1970s Hollywood films (BONNIE AND CLYDE, FIVE EASY PIECES) borrow flourishes of Godard’s style, but since the content (and the emphasis on narrative) doesn’t change very much, the result is a jazzier version of Hollywood business-as-usual. I’m reluctant to call a text “Brechtian” unless it has both radical form and content.

Also, I’m sorry I wasn’t clearer about my “trouble with Brechtianism.” I’m perfectly happy to extend my skepticism about texts controlling audience/spectator/reader response to ALL texts, Brechtian, Hollywood, and otherwise. I stick close to the Cultural Studies belief that a text generates a multiplicity of responses, only some of which were anticipated by the creator(s) of said text. That doesn’t mean that Brechtian movies can’t have a radical effect—just that I think our assumptions about their radicalism should be humble and skeptical until proven otherwise.

In her book INTERPRETING FILMS, Janet Staiger argues that films (and the historical moments in which films are watched and discussed) generate a plethora of reading strategies, though some of these are much more dominant than others. I relied on Staiger’s work in my dissertation, where I argued that US critics read Godard’s late 1960s and Dziga Vertov films in many different ways, though by far the dominant reading was to co-opt them into a conservative “Godard as auteur” paradigm. That’s happened here at HU too: the thread following John and Sandra’s post is a list of favorite directors formidable enough to make Andrew Sarris blush. But is there tension in claiming that Lynch, Bresson or Godard are “radical” while admitting them to the canon and labeling them “great artists”?

__________

Images of Godard and Brecht with 3-D glasses from BRRRPTZZAP! the Subject.

The index to the Godard roundtable is here.

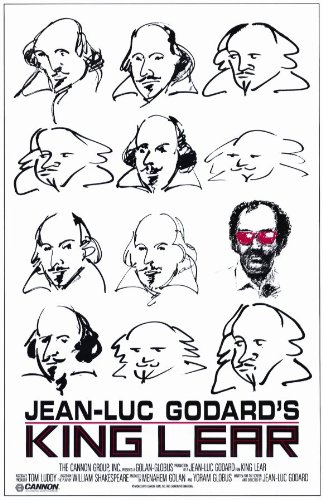

A Film Shot in the Back

Caro asked me, as her go-to guy on things King Lear, to write up some thoughts for the Hoodlum Unitarian roundtable. I can therefore say with assurance that the key to understanding Godard’s 1987 King Lear, unlike most productions of the Shakespeare play, is Charles Bronson’s Death Wish 4: The Crackdown.

What, haven’t seen it? Fate has been kind enough to me that I can say the same. I’m thinking more about what it has in common with Bo Derek’s post-10 bomb Bolero, Superman IV: The Quest for Peace, the Raiders of the Lost Ark knock-off King Solomon’s Mines, and another movie I won’t even bother to name but whose Wikipedia plot summary begins: “A female aerobic instructor is possessed by an evil spirit of a fallen ninja…”

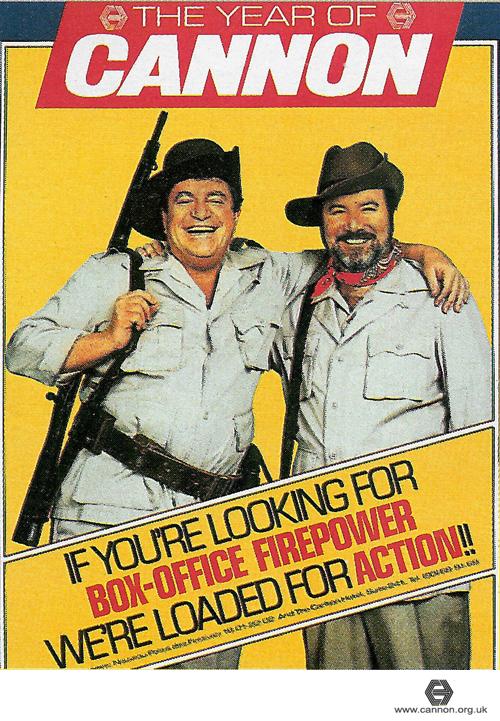

This collection of infinitesimally budgeted squeezings from tapped-out franchises all share a common source: the Cannon Film Group, in that period from 1979 to 1988 when it was owned by the Israeli duo Menachem Golam and Yoram Globus.

While Golam and Globus may have been schlockmeisters without peer, they were schlockmeisters with occasional cultural ambitions and/or pretensions. And near the end of their control of the Cannon Film Group, Jean-Luc Godard decided to take those ambitions for a joyride.

King Lear has, among all his other problems with the universe, a spotty film career.

At the moment, the text of King Lear is probably best known in Hollywood for being misquoted in a tattoo on Megan Fox’s back. (Lear Life Lesson: don’t get tattoos in parlors without internet access; the skin you save may be your own.) The first film version of King Lear predates sound, which means either Panto Lear or the world’s densest title cards. It was sixteen minutes long.

There have been some really good television productions — Laurence Olivier, Michael Hordern (my fave), Ian Holm, Ian McKellen, Orson Welles — but trips to the big screen have been rare. In my lifetime there’s been a Russian production under Grigori Kosintsev, and it’s inexplicable that I haven’t seen it; doubly inexplicable given that it’s got an original score by Dmitri Shostakovich. There’s the existential despair-fest of Peter Brook, milking every drop of downericity. Al Pacino has announced plans, and I’m pretty excited about it, but apparently now it is about as likely to get made as Atlas Shrugged: Part II.

And then there’s this thing.

Would you be surprised if I said that Godard’s take on King Lear was not exceptionally literal? That there’s probably more actual Lear in the 16-minute silent version?

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ybOhr-RtAas&feature=youtu.be

Before the opening credits, there is a recording of a phone conversation.

Godard: “Well… uh…”

Either Golem or Globus: “Let me tell in short, two sentences, my main concern.”

Godard: “Yes, of course.”

Either Golem or Globus: “My main concern is the concern of the company and the prestige of Cannon Group. Cannon has announced for a year and a half [at this point the cheerful baroque accompaniment skids into the ditch, as of someone pulled the phonograph plug] Jean-Luc Godard’s movie, ‘King Lear.’ It is not believed by many that the movie will ever be done. We are losing confidence. We are losing our name. I, I must insist that this movie, as promised, which was already postponed so many times, will reach the Cannes festival. This is my main concern.”

An unidentified but lawyerly voice on the other end of the phone says: “Okay, Jean-Luc, why don’t you respond to that.”

The movie is his response.

The film proper begins, actually, with a line about Norman Mailer: “Mailer. Oh yes, that is a good way to begin.” The line is delivered by, naturally, Norman Mailer.

Mailer, uncredited, playing a Very Famous Writer, has decided that King Lear works better if stripped to its essence. And its essence, as the Very Famous Writer sees it, is a Mafia movie: Don Learo, Don Kenny, Don Gloucestro…

And then the movie starts over again: a different take of the same scene — Mailer and his daughter Kate, discussing his approach and then, for more context, reading the contract they signed with Godard. Intercut are a series of title cards, as the movie tries to decide what it’s name is. “King Lear: A Study.” “King Lear: A Clearing.” “King Lear: Fear and Loathing.” “A Film Shot in the Back.” The titles continue to pop up through out the movie, prematurely announcing THE END more than once.

Our main character turns out not to be Don Learo — although he does show up, played by Burgess Meredith, uncredited — but William Shakespare Junior the Fifth (Peter Sellars, uncredited, who would later clean up as a director of opera).

The situation in the world is dire, Shakespeare Jr. V explains in voice-over: “And suddenly it was the time of Chernobyl, and everything disappeared. Everything. And then after a while, everything came back. Electricity, houses, cars. Everything except culture — and meat. My task: to recapture what was lost. Starting with the works of my famous ancestor.”

Later we see him going through a forest with a butterfly net; he exultantly spots a reel of film in a pond. Cultural rescue to the rescue! By scribbling down bits of overheard conversation between Learo and his daughter Cordelia (Molly Ringwald!) he intends to recreate the text, or at least some text.

At this point it should be pretty clear that continuing with a plot summary is not that useful of an exercise. The movie is as fragmented as the scraps of Lear that waft through, sometimes by disembodied voices on the soundtrack, interrupted by the screeching of sea gulls.

This disjointed fragments-I-have-shored quality also gives it the freedom to swing wildly between two different modes.

On one hand, there is ponderous lecturing on the meaning of cinema, given mostly by Professor Pluggy, from whom Shakespeare Jr. V seeks advice. He comes by his name honestly enough: he’s wearing spiralling patch cords as dreadlocks. It’s also, not coincidentally, Jean-Luc Godard. Perhaps he is reciting some classic work of film interpretation, but it drags on tediously, as if he’s intending to bore his audience intentionally.

The other mode is a kind of improvisatory, vaudevillian jokiness. Here is Don Learo, over dinner, discussing Jewish gangsters Bugsy Seigel and Meyer Lansky: “Bugsy was a real killer. Not like this — uh, Richard Nixon.” In this vein, it’s not surprising that Woody Allen has a walk-on.

So how do you explain a movie like this? You have to use the Hebrew word freier — sucker. Golem and Globus, eager to do a prestige picture to mitigate their schlockmeisterhood, thought that underwriting a movie from Jean-Luc Godard was their fast lane to Cannes. They did not expect that they, themselves, would be the freiers.

The movie looks very much like a lark. Paid for by the Cannon Film Group.

______________

The Godard Roundtable index is here.

One Plus One, or the Ruse of Analogy

To begin with, a generalization: Godardians really don’t like Quentin Tarantino. But, fear not, this post isn’t going to be about the latter, only the reasons expressed by the Godardians for their contempt. Wasn’t it Jean-Luc Godard himself who argued against a clear distinction between the fictional film and the documentary? For him, being even more opposed to naïve realism than Andre Bazin, the camera always had a perspective, a position, or as Colin MacCabe puts it: “there is not reality and then the camera – there is reality seized at this moment and this way by the camera.” [p. 79] It was this foundational belief that led to Godard’s dismissal of the anti-aesthetic implicit within cinema vérité, that reality comes from letting the film roll. Yet, Jonathan Rosenbaum (and I might as well mention Daniel Mendelsohn and HU’s very own Caroline Small) condemns Inglourious Basterds for “mak[ing] the Holocaust harder, not easier to grasp as a historical reality,” because “anything that makes Fascism unreal is wrong.” Evidently, fascism is just there waiting to have a camera pointed at it. No truth could possibly come out of a fantasy involving Nazism. In One Plus One, Godard films a neo-Nazi pornographic bookseller reading from Mein Kampf as his customers buy lurid novels and magazines — each person who makes a purchase gives a Nazi salute and slaps two captured hippies in the face. Is Godard making fascism easier to understand as a historical reality? More likely, the viewer is confused at this unrealistic scenario, but hopefully intrigued (or entertained) enough to contemplate what all these component images are doing there together in the middle of a rockumentary, e.g..: What does pornography have to do with fascism? What does any of this have to do with The Rolling Stones (the ostensible subject)? Just what the hell is Godard saying?

Rosenbaum refuses to regard Tarantino with any sort of reflection (I suspect too much identification, aka “entertainment,” and not enough distanciation aka “intellectual thought”). Inglourious Basterds is a film about other films, about movie conventions, and for that reason alone, “it loses its historical reality.” However, aren’t all of Godard’s quotations from films, news media, advertising and literature committed to the exact opposite point, that these images do have a historical reality in the way they construct/mediate who we are? If one is going to be derided for his narcissistic cinephilia (filtering everything through film), then the other should be, too. Rosenbaum mockingly quotes from an interview with Tarantino where he relates the 9/11 event to the spectacle of action films – not one of the director’s prouder moments, to be sure. Now consider Godard’s statement from La Chinoise’s press book:

Fifty years after the October Revolution, American cinema dominates world cinema. There’s not much to add to this state of affairs. Only that at our modest level, we must also create two or three Vietnams at the heart of the immense empire, Hollywood-Cinecittà-Mosfilms-Pinewood, etc. as much economic as aesthetic, that’s to say struggling on two fronts, to create national cinemas, free, brotherly, comrades and friends. [p. 182, MacCabe]

Although MacCabe gives this a sympathetic spin, noting how Godard has always been aware that his “oppression” isn’t as “grievous” as what was done to the Vietnamese, there’s not much he can do with the foolhardiness of the director’s feeling “solidarity” with them because “his own experience” is “the very same predicament.” I’m going to assume that the imperialism of having too many theaters showing American movies is quite obviously not the oppression of a napalm bath, as a spectacle or otherwise, and move on.

On the other hand, Godard’s kinocentrism (sounds better than ‘cinecentrism’) also served to make him film’s most indefatigable and important moral critic of the Sixties – at least, regarding his chosen medium (as we’ll see, I’m more skeptical of his role as a social critic). If his films of that period are about any one topic, it’s the relation of cinematic form to reality, how one shapes the other, and the filmmaker’s charge in relating his or her film to an audience. As our reality was becoming increasingly mediated by images, where the representation of life was replacing life and human relations were displaced through commodities (compare Pierrot le fou’s famous dinner party scene in which the guests communicate through ad-speak to Guy Debord’s Society of the Spectacle), Godard radicalized his films in Brechtian fashion by subverting cinema’s conventions, calling attention to their mediating effects (albeit Debord and the Situationists weren’t fans): music pops up arbitrarily, dialogue doesn’t sync with the images, quotes (both visual and textual) are used in abundance but frequently have no logical connection to what little plot is involved, etc. As the title sequence for 1965’s Pierrot le fou fades to just the O’s, Godard, relating to the world through cinema, but ever more distrustful of the reality of images, announced his intent, to return filmmaking to degree zero. His films would become more radical (and more impenetrable to the average filmgoer).

Ever since I first saw it, One Plus One has alternately bored, frustrated and fascinated me in roughly equal measure. Godard called it his last bourgeois film, since it was the last of the period (following Week End) to be financed through conventional means and wasn’t as collaboratively directed as his subsequent efforts with the Maoist Dziga Vertov Group (where the group received auteur credit and they would try to make films via committee). Indeed, other than featuring The Rolling Stones, the film is probably best known by the incident where the director punched his producer, Iain Quarrier (who plays the bookseller), in the nose for having altered the ending to include the completed version of “Sympathy for the Devil” and renaming the film with the song title – that is, Godard hadn’t abandoned all vestiges of his own auteurship. Nevertheless, it was the first of his films to follow the transformative events of the Langlois Affair and May 1968, a transition into what’s typically known as his radical period, where he and his collaborators (particularly Jean-Pierre Gorin) attempted to realize the revolutionary potential of film.

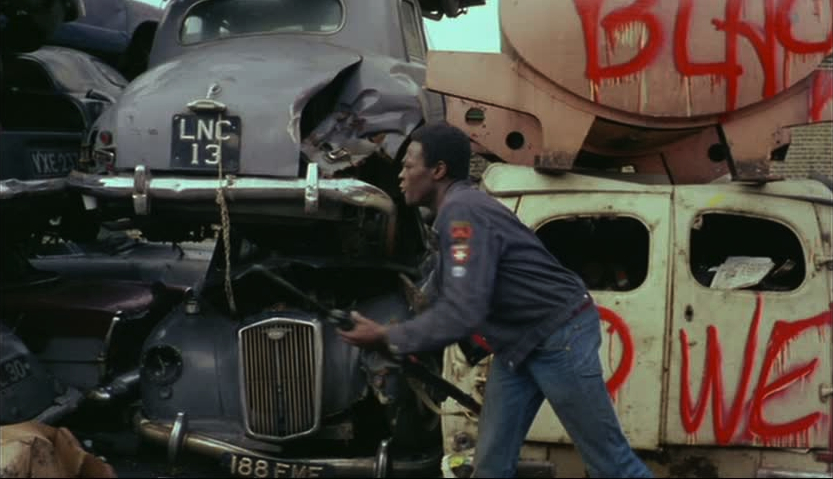

Through long tracking shots between the band members in a recording studio, each often surrounded by soundboards, the film conveys the amount of individual effort and labor time involved, 1 + 1, even in manufacturing something as seemingly disposable as a pop song. By refusing to give the audience the finished version (in the director’s cut), the focus is on the collaboration, rather than the commodity. Likewise, the mise-en-scène is an attempt to not single out any particular member as a star (although, unsurprisingly, Mick Jagger and Keith Richards speak more than the rest while the drug-addled Brian Jones nearly vanishes on camera). Against the visual images, a narrator reads from a smutty political novel (involving, among others, Pope Paul and LBJ in lascivious encounters), which intrudes upon the traditionally diegetic sound, dialectically challenging the notion of a unified film diegesis. And against The Stones in the studio, Godard counterposes other, tenuously related sequences: the media interrogation and eventual demise of Eve Democracy (Anne Wiazemsky, JLG’s second wife); in a junkyard, black militants read Black Power disquisitions, pass guns to each other (within long lateral tracking shots) as they molest and slaughter white women; and there’s the aforementioned bookstore where men and women, old and young, bourgeois and working classes can purchase smut and racist, violent pulp. To quote Mao Zedong (lifted from Slavoj Žižek): “In any given thing, the unity of opposites is conditional, temporary and transitory, and hence relative, whereas the struggle of opposites is absolute.” Godard is quite brilliant in formally instantiating Mao’s “the one divides into the two,” forcing the viewer to engage the filmic elements dialectically, but does the film effect any change outside of cinema, or even demand such a change?

I’m inclined towards Roger Greenspun’s early summation: “Whatever its intentions, One Plus One contemplates rather than advocates revolution.” It’s about the use of revolutionary ideas to make a film, rather than a film serving the revolution. Exploiting The Rolling Stones’ popularity could’ve been advantageous to spreading radical ideas to the masses, but not when it takes something like an intellectual interpretation of Mao to understand those ideas. The film could only fail in its didactic purpose, since it was ultimately aimed at other cinephiles already sympathizing with the ideology – i.e., white bourgeois radicals, the type of person who really gets the joke of juxtaposing a successful blues-based rock band against a black militant reading LeRoi Jones on the white appropriation of black music. But is Godard doing anything differently here? He uses the image of black militancy to lend authenticity to his kinocentric radicalism much like he analogized his own oppression to that of the Vietnamese, as if he’s there with them in the junkyard – the void of Western culture. At least The Stones have a genuine love for the American Blues. I’m not so sure that Godard expresses anything more than a narcissistic interest in the struggle of American blacks (namely, what it might mean to his ideas of a revolutionary cinema). Since I find this representative of a certain navel-gazing self-importance endemic to Godard’s films (what most of his detractors would call ‘boring’), I’m going to focus the rest of the essay on what’s problematic about his use of black representation.

First, consider this more favorable interpretation from Gary Elshaw (providing the most insightful and comprehensive critique of the film that I’ve found):

Godard’s desire to “destroy culture” is illustrated by [Eldridge] Cleaver’s own desire to destroy the dominant culture, a culture that is led in the form of the ‘Omnipotent Administrator’. The ‘Omnipotent Administrator’ represents white male patriarchal power, a power which often manifested itself as governmental and repressive.

Contrariwise, I find a bit of minstrelsy in Godard’s use of black men in that it’s a savage image, regardless of their literary references. Now, I understand that their violence stems from what he surely agrees is white oppression, but their abstracted appearance here is more a metaphor for his own struggle to destroy the Hollywood Empire’s hegemony than to capture the reality of blackness. Black Power is to Godard’s target audience what Leadbelly was to the “open-minded,” left-leaning white audiences of his time. As Hugh Barker and Yuval Taylor put it (in their book Faking It: The Quest for Authenticity in Popular Music): “[B]y the twentieth century, with the influence of Darwin and Freud, it was primarily the Negro who had become idealized, and this time as the primitive – pure id, and therefore profound.” [p. 10] Despite the soft-spoken musician’s preference for suits, his promoter and producer, John Lomax, insisted on the commodified image of the prison-garbed, convicted murderer, selling an idea of authentic repression by reflecting (however well-meaning) white bias. Isn’t this what Godard’s doing with the black militants, by presenting the violent return of the repressed black to white radicals calling – at least, intellectually – for a violent revolution? Solidarity, go primitive, back to zero. Eve Democracy dies while fighting beside blacks on a beach at the end. As the most likely stand-in for the director (espousing many of his views during the interview earlier), that it’s her corpse raised on the Hollywood-sized camera crane (Godard’s “omnipotent administrator”) in the last shot is, I believe, telling.

My triangulation is similar to the scene in Week End where two previously warring parties, an anti-Semitic woman and a communist farmer, are united in their disdain at the self-centeredness of the lead bourgeois couple, Corinne and Roland. As Frank B. Wilderson III argues (in Red, White & Black):

[T]he imaginative labor of White radicalism and White political cinema is animated by the same ensemble of questions and the same structure of feeling that animates White supremacy. Which is to say that while the men and women in blue, with guns and jailers’ keys, appear to be White supremacy’s front line of violence against Blacks, they are merely its reserves, called on only when needed to augment White radicalism’s always already ongoing patrol of a zone more sacred than the streets: the zone of White ethical dilemmas, of civil society at every scale, from the White body, to the White household, through the public sphere on up to the nation. [p. 131; capitalized White and Black refer to structural positions]

By being a reflection of his kinocentrism – cinephilia his “zone of White ethical dilemmas” – Godard’s attempted solidarity with the American Black Power movement becomes aligned with early twentieth century white condescension. On the one hand, there’s the offense at Henri Langlois being unjustly removed from the Cinémathèque Française and, on the other, there’s former Slausons member Kumasi’s memory of the Watts Riots (from the film Crips & Bloods: Made in America):

You cannot woop us. We’re already dead. We’re already beaten down — we’ve been beaten down for 400 years. We already got the wounds inside and outside our bodies; how you gonna hurt us? […] Here’s a dilapidated building; ain’t nobody livin’ there. You didn’t fix it; you didn’t remove it, okay? It ain’t nothing but a pile of bricks, anyhow. That’s comin’ at you. That whole building, brick by brick, is comin’ at yo’ ass. That’s what we’re throwin’ at you: the building, the bullshit, the rubble, the rubbish that we live in. That’s what’s comin’ at yo’ ass. Those are our weapons: the filth, the funk, the shit that you can’t stand — that you defend, that you put a barrier between us and yo’self. That’s comin’ at you.

Wilderson would argue that these two forms of oppression aren’t just different in degree, but in ontological kind. Godard’s attempt to draw a structural parallel (say, between the censoring of films under the de Gaulle regime and the way the black population was cordoned off in Southern Los Angeles) is based on a false analogy. This “ruse,” as Wilderson calls it, hides the ontological violence perpetrated on blacks through slavery, whereby Blackness became defined as fungibility and accumulation – Inhuman, Dead. As for the communist struggle, quoting Wilderson again: “workers labor on the commodity, they are not the commodity itself, their labor power is.” [p. 50] Not that it would be much more plausible, but Godard should’ve kept his analogies of oppression to those of the striking workers in May 1968, since they were struggling with alienation and exploitation, not necessarily their position as Human. It was his solipsism that ensured One Plus One would be best remembered for its formal inventiveness or, most often (for example), as a collection of snazzy clips of The Stones at the beginning of their most inventive period.

REFERENCES (not all of them cited in the text):

Hugh Barker & Yuval Taylor, Faking It: The Quest for Authenticity in Popular Music

Gary Elshaw, “The Depiction of Late 1960s’ Counter Culture in Jean-Luc Godard’s One Plus One/Sympathy for the Devil”

Stephen Glynn, “Sympathy for the Devil”

Roger Greenspan, “Sympathy for the Devil (1+1)”

Colin MacCabe, Godard: A Portrait of the Artist at Seventy

David Sterritt, The Films of Jean-Luc Godard

Donato Totaro, “May 1968 and After: Cinema in France and Beyond”

Frank B. Wilderson, III, Red, White & Black: Cinema and the Structure of U.S. Antagonisms

Slavoj Žižek, “Mao Zedong: The Marxist Lord of Misrule”

______________

The Godard Roundtable index is here.