I tend to be a careless reader on first reading a book. I’m distracted. I’m too interested in just getting through. I’m testing the waters too much: do I like this, will I like this? For this reason, I’m a big rereader. I try not to review anything on only one read. Better with two or three reads, then I have a sense of the book as a whole, the overarching picture, and I can start looking at the details and putting together the pieces. If I can’t make it through a second time, then I know I shouldn’t be writing about the work. I can make it twice through most books. Three times, though, four times, those are the ones that go a little further, where there are always new connections to make between the words, the pictures, and the ideas.

I read Asterios Polyp very quickly when I first got it. I had picked it up at MoCCA last year and had a train ride through New Jersey to spend reading. I read it again a week or so later. And only a couple months later did I actual write something on the book, sticking to a discussion of the book’s ending (an interpretation, I have stuck to, after my most recent rereadings).

Picking up the book again in anticipation of this roundtable, I found myself a little reluctant. There was a point between then (first reading) and now where I started thinking about the story at the heart of the book. The basic story of Asterios Polyp (both the character and the book) is rather banal. Middle aged man is at a low point in his life and takes a life changing journey that causes him to realize his mistakes and reunite with a loved one. Damn, that sounds real lame, like dozens of popular “indie” films and no doubt hundreds of midlist novels written by middle aged professors.

But, what story isn’t, in some way, a familiar tale. Someone’s always trying to break the plots down into a list (Polti’s Thirty-six Dramatic Situations) or a handy quip (John Gardner: “There are only two plots in all of literature, someone goes on a journey, or a stranger comes to town” [I can’t find the source for this…]) It’s not the base story that really matters, we’ve seen them dozens of times, it’s the execution, it’s the layers piled on top (or hidden underneath), it’s the art and the artifice. It comes down to the author/artist.

And where David Mazzucchelli really shines is in the formal invention he brings to the comic. He’s taken this story and added layers of complexity and formal ingenuity. I’ve read the book a handful of times now, and paged through reading various sequences a few more. I keep finding more elements to attract my attention and stimulate my creativity. Everything feels constructed and purposeful, which some may dislike (I feel like I’ve read complaints in that vein), but to me it breaks me out of thinking “this is real” and allows me to engage on a less mimetic level. I don’t want to think of these characters and events as real. A big part of the enjoyment for me is taking note of how Mazzucchelli uses elements of comics to varying effects, an enjoyment that is no doubt affected by my interest in expanding my work on my own comics. Asterios Polyp often feels very insider-y, despite it not being about a cartoonist.

I’m not one to make larger arguments about theme (I’ll leave that to some of my co-roundtable mates), I’m more of a formalist. I love looking at how comics work and how individual artists make comics work differently. So, in that vein, here are five elements of the work I noticed as I reread it this time around. Some are more developed than others, but maybe the less developed ones can at least spark some discussion in the comments.

1. Balloons and Text

Word balloons are often overlooked in comics, despite being one of those quintessentially iconic images that scream “comics.” Artists tend to vary balloons only slightly: larger or smaller, smooth (speech) or scalloped (thought) or spiky (shouting), ellipse or rectangle. And from one character to the next, artists tend to maintain their style. Hergé uses his rectangles with the cut out corners, Ware seems to stick with rounded rectangles, most use the classic oval balloon (such an inefficient use of space for displaying words). Dave Sim is a master of word balloons, added aural and emotional inflection through the shapes, sizes, and placement of his balloons (not even getting into his use of the text itself), but these moments are for the heightened moments: the shouting, the worry, the whispers, the frantic internal dialogue (lots of internal dialogue in Cerebus). The normal everyday talking is still shown in fairly plain balloons.

I remember early in my comics reading career, being surprised at the way Todd Klein used different types of word balloons for some of the characters in Sandman (I’ll credit Klein, but the idea could have come from Gaiman or one of the artists). Each of the Endless seemed have their own way of speaking: Dream with his black balloons with the wavy white border, Delirium with her rainbow hued balloons, Despair with a more craggy bordered balloon (see early on in the “Seasons of Mist” storyline for an example with them all together). These variations are an overt way to give those special characters their voices, so to speak.

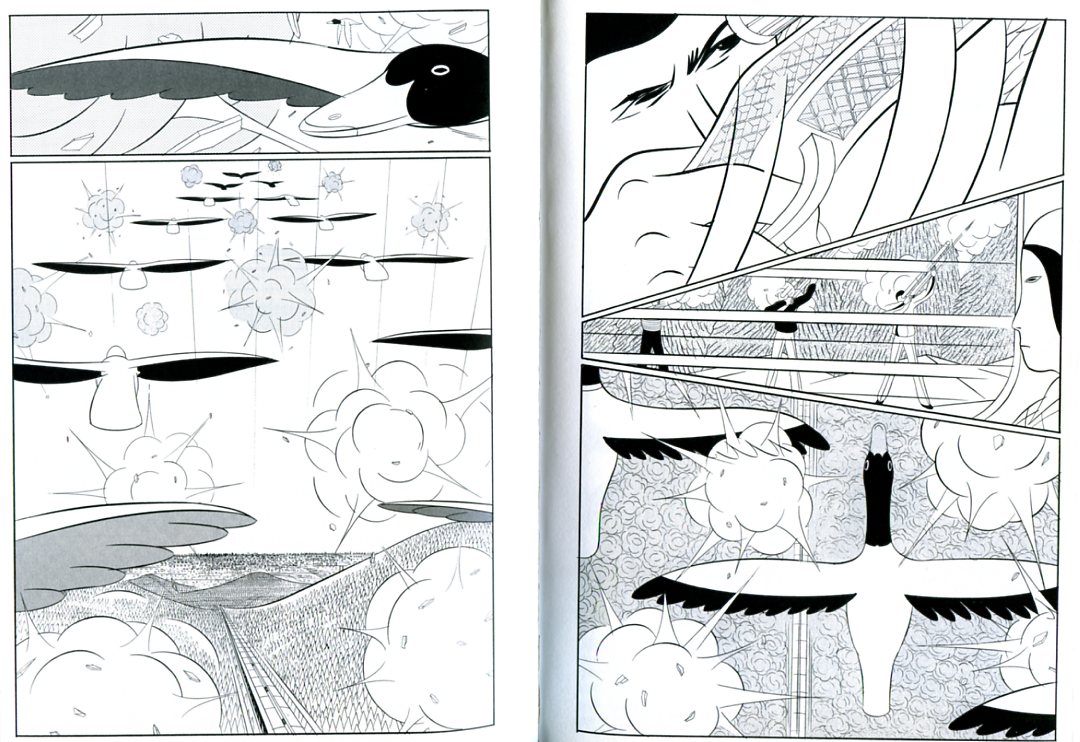

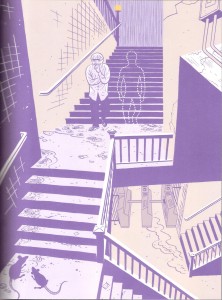

Note different shaped balloons.

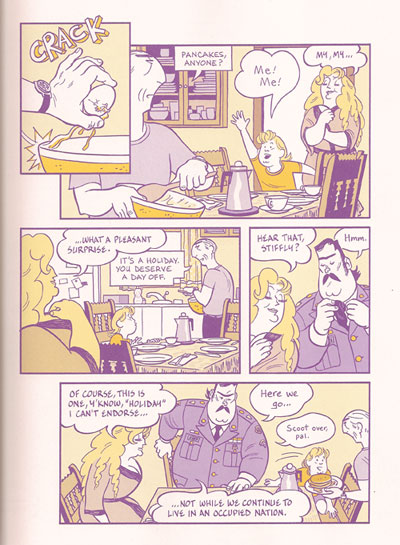

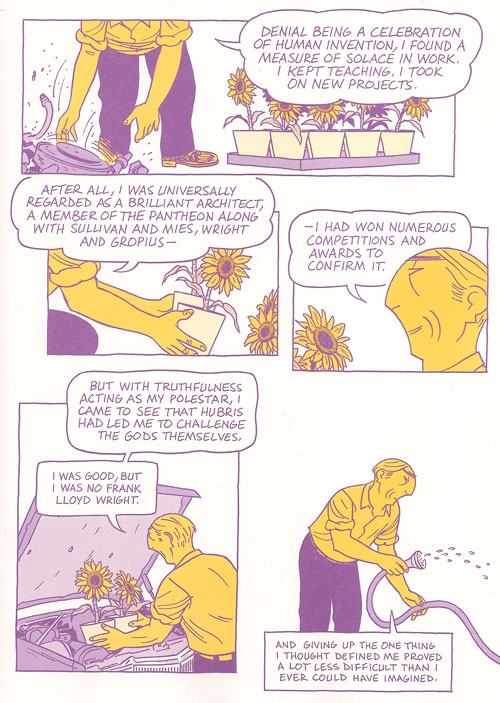

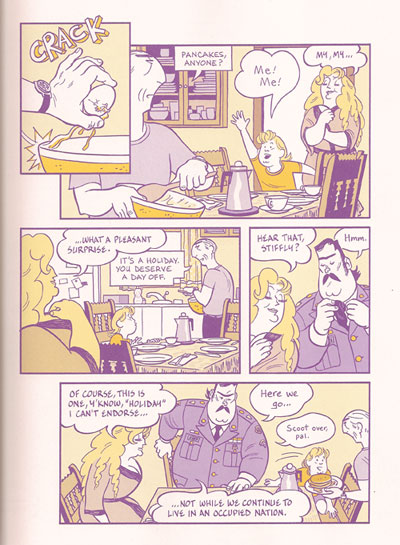

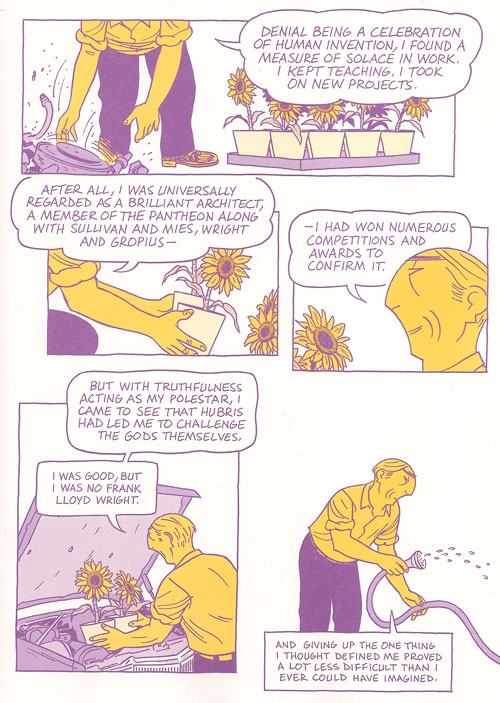

Mazzucchelli takes it to another level. Pretty much every character in Asterios Polyp (even minor ones) has his or her own balloon shape. Asterios’s are rectangular with hard edges. Hana’s are like teardrops. Stiffly’s are wavy. Ursula’s are like a large, smoothed out scallop edge. Their son, Jackson, has balloons that are kind of mixing of the two, a larger more wavy scallop (see image above). On one page we see balloons from Hana’s off-panel mother, and they have a distinctive shape: hard edged and chaotic with overlapping corners and oddly sharp angled tails. Even the word balloons coming out of the television that Asterios is watching in the first scene take on slightly distorted shapes of the characters in the video (Asterios and Hana).

Word balloons like narrative captions.

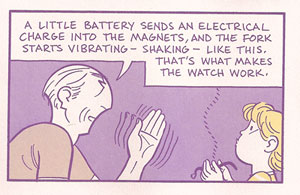

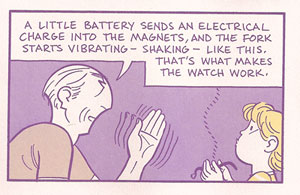

I don’t think it’s a coincidence that Asterios’s rectangular balloons can take on the appearance of the traditional rectangular narrative captions at the top of panels. Asterios is so often pontificating that his words often act like narration. This is rather explicit in the scene where he is explaining his magnetic watch to Jackson. His rectangular balloons fill the top of the panel, just like a caption would.

One unusual one I only noticed on after starting this post, is the balloon that shouts “Hey” after Asterios as he skips under the subway turnstyle. The balloon and lettering takes on the same style and shape as the MTA logo used on the NYC Metrocards. In a similar way, slightly different lettering is used for many of these characters: all caps, normal caps, italic, bold, large, small, and different font faces. Together the combinations give a visual voice to the characters in a way that I don’t recall having ever seen done in such a consistent and extensive way.

I don’t see Mazzucchelli doing this in the book, but his consistency with the balloons and their varied shapes/fonts is such that the reader could identify the speaker without seeing the character. I’d find this type of vocal recognition quite helpful in some manga I’ve read where balloons are often used without tails or without any characters in the panel to mark the speaker.

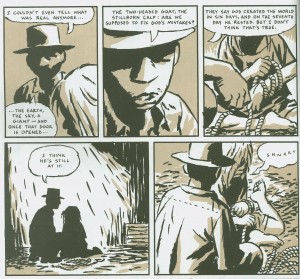

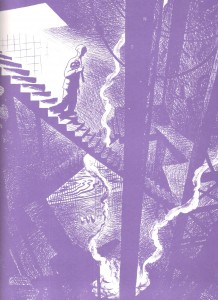

Let me offer one important thematic use of the word balloons. Throughout the dream sequences, Asterios’s dead twin brother Ignazio speaks with a scalloped balloon that is quite reminiscent of a thought balloon. Towards the end of the book, just before Asterios wakes up in the hospital, he dreams about Ignazio. Asterios finds him at the garage, working on a car. Ignazio starts talking, reusing many of the words from his narration about Asterios at the beginning of the book. He is talking in the first person as if he had lived Asterios’s life, and slowly his word balloons transform, morphing from a round scalloped shape into the sharp rectangles of Asterios’s balloons (see image below).

Word balloons transform.

This scene is an important moment in the book, one I neglected to realize the significance of before I noticed this use of the word balloons. Ignazio, with his thought balloon like speech, is just Asterios’s obsession with duality taking on life. And here, at the end of the book, Asterios has his epiphany. Ignazio transforms back into Asterios, the pompous Asterios of the past, and Asterios kills him.

2. A Bit on the Colors

Mazzucchelli’s color work in Rubber Blanket was a revelation of sorts to me about the power of a limited color palette using transparency to create blends (I wrote a bit about that previously). Asterios Polyp at first seems like it’s using a similarly harshly restricted color palette. When I read it, I try to pick out the colors, to count the shades. I never really succeed in figuring out how many colors there are, it always seems to be more than I first think.

But, there is a limit on the number of hues used at any one time, and Mazzuchelli makes great use of these variations and shifts in palette. The purple and yellow of Asterios’s journey in the present presents itself early on in the book, but only after the strike of lightning seems to steal all the blue. The blue and pink are the colors of the past, taking the clichéd blue=boys pink=girls and making it a powerful visual cue to the relationship between Asterios and Hana. In a sense these palettes play into the duality tension that fills the book. The purple/yellow palette are complements, opposites on the color wheel, yet they are more than just two colors. There are the shades of both. There is the fact that purple itself is a mixing of blue and red. The duality is surface, and it dissolves with attention.

Various hues also take prominence to create shifts in the narrative. Dreams are suffused with yellow. Flashbacks (see Asterios remembering his father as he rides the bus holding his lighter) are suffused with blue. In a way, this use of color is a variation on the classic trope of the altered panel border to indicate flashbacks or dream sequences.

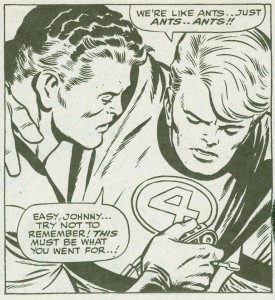

Greenish tones enter.

The color I noticed this past read is green. After the dominance of purple, blue, yellow, and pink, green sneaks in late in the story. When Asterios wakes up in the hospital after getting hit by the drunk in the bar (and after the dream sequence I mentioned above), some of the blues take on a greenish hue (see image above). The greenish blue seems to become more bluish green over the course of a few pages until Asterios is in his solar-powered car leaving town, and a bright green interstate sign jumps forward at the very top of the page. This green sign is in itself a sign that a fuller color palette has arrived. We can easily connect this expanding palette with Asterios’s new perspective and all the commentary in the book about perspective and “coloring” the way we experience life.

It must be telling in some way that Hana, in her final scene appears wearing a green shirt. In a way, the couple have almost switched colors in this scene. Asterios wears a pinkish purple shirt, while Hana wears bluish green pants. A final color shift to represent their reconciliation.

3. Back to that Ending

Asterios Polyp is both a comedy and a tragedy, in my reading. It ends with marriage (reconciliation) and death (I continue to read the asteroid as about to strike the house where Hana and Asterios sit). Furthering the idea that once you start looking for those dualities they are everywhere, but the two poles never seem to stay clearly separated.

4. Brushwork

When I saw Mazzucchelli at MoCCA when the book made it’s debut, he was drawing Asterios’s head with a compass as he did in the book. Much of the comic has a similar precise line and flat, sharp color fields. But there are moments of looser brushwork that has an almost dry brush appearance. Only a few of these tiny moments pepper the book. I’m at a loss to explain this tiny stylistic shift spread out across the book. Perhaps they have no explanation other than being the best way to portray the image in question. These moments catch my attention and are quite lovely in themselves.

It starts with the storm clouds and lightning strikes and ends with the asteroid hurtling towards Hana’s house. But in between are these two moments that are almost polar opposites in their placement of the Asterios/Hana relationship. First:

The large rock Hana sits on at the beach when they find the Swiss Army knife. (Sidenote: In the MoCCA Mazzucchelli show that was up, they had the original art for this page, including the second version of this rock that he drew on a separate paper and edited (Photoshopped, one assumes) into the page over the original one.) This image is accompanied by narration concerning their marriage.

Walking home from the composer’s apartment, later in the story, just before their relationship really breaks, this snow covered fire hydrant sits in the lower corner of a panel.

Could these perhaps be another case of the coloring of perception? Tiny moments of grace in another wise cut and dried world. A tiny nod towards paying more attention (as Hana has it) to the world around us. Each of these images are nature based, a softness against the hard edges of Asterios’s architecture.

5. Large Panels of Rooms

Mazzucchelli uses a lot of large panels (usually about two-thirds of the page) to show us interiors. From our first view of Asterios’s apartment to him shivering on the couch of Hana’s house after his long snowy walk, these large panel rooms set scenes, expose psychology, and position relationships. Many of these panels show the rooms from the same point of view, in particular, we see Asterios’s living room a number of times through the course of the book.

Perhaps the most effective use of these large rooms is Asterios sitting on a bed with a blister on his foot. His static position is placed onto two separate bedrooms at two different times, his repeated phrase bringing on a torrent of memories (and one of the best scenes in the book, in my opinion).

So there you have it. A few thoughts on the book.

Having written all of this before reading Noah’s post from yesterday, should I be chagrined to have fallen into the traps of “what I’m supposed to do with the book”? Oddly, I agree with Noah about the characters and the story, the thing is, I just “so don’t care.” I’ll get my pleasures from other parts of the book.

—

This is the second post in a roundtable on Asterios Polyp. Regular Utilitarian, Richard Cook will weigh in tomorrow, with other Utilitarians and guests posting through next Monday. You can read all the posts in the roundtable on this page.