Science-fiction draws many of its themes, and much of its emotional force, from colonialism. So argues John Rieder in Colonialism and the Emergence of Science Fiction, and he makes a pretty compelling case. To take perhaps the most obvious example, H.G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds derives its plot from a reversal of colonial roles; instead of the invaders, the British become the invaded. The book’s horror is derived from imagining oneself undergoing the trauma that one has inflicted on others — the terror of first contact; the subjugation to superior weapons; the wholesale destruction of one’s civilization; even the ultimate humiliation of watching your fellows betray you to the new overlords. The book can be seen either/both as a satire or critique of colonialism, and as a self-serving disavowal of responsibility — a way to see oneself as sinned against either to sympathize with the oppressed or to deny one’s status as sinner.

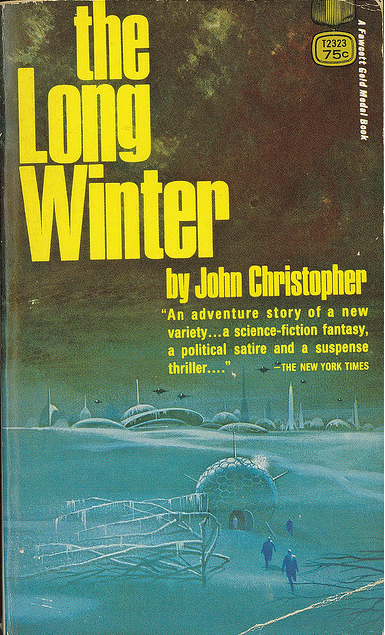

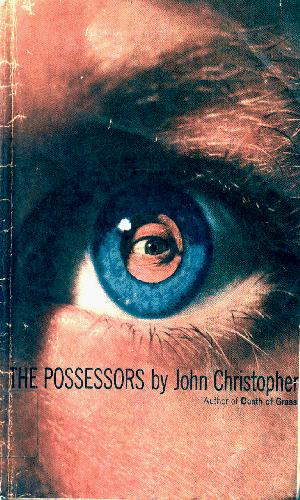

John Christopher’s novel The Possessors was written in 1964, long after the period that Rieder discusses. Yet here to colonialism is an important touchstone — and in similar ways. The novel is (a probably intentional variation on John W. Campbell’s short story “Who Goes There?”) is set in an Alpine skiing chalet. An alien spore, long buried in the snow, is exhumed by a rockslide, and begins to possess the vacationers one by one. The novel features unusually deft and vivid characterization, which makes the possessions especially frightening. Christopher gives us real people with complicated pasts and presents, and then erases them.

John Christopher’s novel The Possessors was written in 1964, long after the period that Rieder discusses. Yet here to colonialism is an important touchstone — and in similar ways. The novel is (a probably intentional variation on John W. Campbell’s short story “Who Goes There?”) is set in an Alpine skiing chalet. An alien spore, long buried in the snow, is exhumed by a rockslide, and begins to possess the vacationers one by one. The novel features unusually deft and vivid characterization, which makes the possessions especially frightening. Christopher gives us real people with complicated pasts and presents, and then erases them.

Imperialism here, of course, is not by sheer force of arms — in fact, when they are taken over by the possessors, humans become less physically threatening — they are slower and clumsier (though better able to survive extremes of cold.) Instead, the invasion occurs through stealth and corruption — an extension of the cultural betrayal that Wells touches on in the War of the Worlds when he mentions humans hunting other humans on behalf of the Martians.

The shift from overt to covert overthrow has, presumably, something to do with the Cold War. The enemy operates through misdirection and persuasion; conquering first by weakening from within. This isn’t so much a variation on Wells as it is a completion, or perfection, of his themes. Again, in the War of the Worlds, the invaders take the place of the invaded; here, the same thing happens, only moreso. In this sense, for Christopher science fiction tropes don’t merely become a metaphor for the Cold War — rather, the Western narrative of Communism is actually revealed as itself a science-fiction trope. The nightmare of Communist infiltration, the fear of turning into the enemy, is a story first told by sci-fi writers, for whom imperial invasion was preceded/enabled by becoming the other.

Again, it’s possible to see The War of the Worlds as a satire of imperialism if you squint a little. In more fully embodying the tropes, though, the Possessors closes down some of the ambiguity. Identifying with the enemy is a possibility, but one that is explicitly condemned and linked to weakness when Mandy is mentally persuaded to join the possessors “freely”, implicitly because they prey upon her alcoholism and loneliness. Moreover, the transformation/invasion of self is explicitly compared to a rape — or, as Christopher puts it, to “a grotesque and hideous mass rape of the soul rather than the body.”

In The Possessors, then, it’s much clearer that the image of the self as invaded is not a way to sympathize, but is rather a justification for not sympathizing. Indeed, it becomes an excuse for genocidal violence, as Selby, a plastic surgeon who gradually becomes the book’s protagonist, explains:

If this thing is an intelligence, and alien, then there is one thing it must know — that there can be question of toleration between it and us. We have to wipe it out, if we are not going to be assimilated by it.

This isn’t actually especially logical. The humans know little or nothing for sure about the alien. Indeed, they don’t even know it’s an alien, really. They now that a bunch of folks have gone nuts, and appear to be acting in concert to recruit others. That’s it. They don’t know for sure that talking wouldn’t help; they don’t know that reconciliation is impossible — they don’t even know what they’re reconciling with, or whether the folks out there — who sure look like their former friends — could be bargained with or talked to.

Nonetheless, the book makes clear that Selby is right, about everything. Christopher provides us with a little narration at the beginning and in other parts of the book so that we know what the threat is better than the characters do. So we find out that the characters are facing an alien intelligence and that that intelligence does in fact take over entire planets. Extermination is necessary. And so, when children and one’s own sisters and wives are all burned to death in the cleansing fire, there is sadness but no guilt or questioning. Invasion must be punished by death, even if (especially if?) the invaders look just like us.

This truth is re-affirmed, with a brilliant twist, in the much-lauded 1946 novella, Vintage Season, by C.L. Moore, a pseudonym for Henry Kuttner and Catherine L. Moore. In the story, the protagonist, Oliver Wilson, rents his house to a group of three mysteriously awe-inspiring strangers for a surprisingly large amount of money. Here’s a description:

The man went first. He was tall and dark and he wore his clothes and carried his body with that peculiar arrogant assurance that comes from perfect confidence in every phase of one’s being. The two women were laughing as they followed him. Their voices were light and sweet, and their faces were beautiful, each in its own exotic way, but the first thing Oliver thought of when he looked at them was: Expensive!

It was not only that patina of perfection that seemed to dwell in every line of their incredibly flawless garments. There are degrees of wealth beyond which wealth itself ceases to have significance. Oliver has seen before, on rare occasions, something like this assurance that the earth turning beneath their well-shod feet turned only to their whim.

Eventually, Oliver discovers where that aura of certainty comes from. These are not visitors from another country; they are visitors from the future. They have traveled back in time to Oliver’s day because it is a historically glorious spring.

Or so they say. As it turns out, the attraction was not exactly the spring, but its end. The visitors have come to watch a catastrophic asteroid hit, which impacts near Oliver’s house. The asteroid unleashes a plague which kills we-don’t-know-quite-how-many, but presumably millions, if not billions. Moreover, Oliver realizes, the visitors — including a women who becomes Oliver’s lover — are inoculated against the plague. They could have saved Oliver, and everyone else, if they wanted to. They did not because they liked their own time, had no wish to change it by changing the past…and perhaps most of all, because they couldn’t be bothered. Thus Oliver’s thoughts after the asteroid.

Revulsion shook him. Remembering the touch of Kleph’s lips, he felt a sour sickness on his tongue. Alluring she had been: he knew that too well. But the aftermath —

There was something about this race from the future. He had felt it dimly at first, before Kleph’s nearness had drowned caution and buffered his sensibilities. Time traveling purely as an escape mechanism seemed almost blasphemous. A race with such power—

Kleph—leaving him for the barbaric splendid cornoation at Rome a thousand years ago-how had she seen him? Not as a living breathing man. He knew that, very certainly Kleph’s race were spectators.

The visitors, then, are tourists, whose entertainment is the suffering and death of those who have made their luxurious lifestyle possible. As John Rieder writes, “The inevitability of history becomes rather difficult to tell apart from a naturalizing ideology that protects and disavows responsibility for the hierarchical difference between the tourists and the natives.”

It’s also worth pointing out, though, that “difference between the tourists and the natives” is in fact no difference. Oliver’s description of the visitors — wealthy, powerful, uncaring, decadent, spectatorial — is also, and surely intentionally, a description of Oliver’s own Western society, which also entertains itself with visions of apocalypse — like, for instance, the novella “Vintage Season.” This parallel is further emphasized by the introduction of Cenbe, an artist from the future who makes artwork incorporating footage of terrible disasters throughout history. His final triumph is a piece involving the events of this story — a piece, which arguably, does the same thing that the novella does.

Like Wells and Christopher, then, Kuttner and Moore present the possibility of our own colonialism being done unto us. And, again, as in those other narratives, the reaction to such self-violation is self-vengeance; the judgement on the callousness of the decadent tourists is fire visited upon decadent tourists — even if, ostensibly, the wrong ones. In most such narratives, of course, the elimination of the other who is the self is seen as the ultimate triumph, a quintessential apotheosis of integration and mastery. For Kuttner and Moore, on the other hand, it is presented as a kind of tragically banal inadequacy, almost as if colonialism, whether for colonized or colonizer, is not a narrative of triumph at all.