Midnight Fishermen: Gekiga of the 1970s by Yoshihiro Tatsumi

Singapore: Landmark Books, 2013. ISBN 978-981-4189-38-5

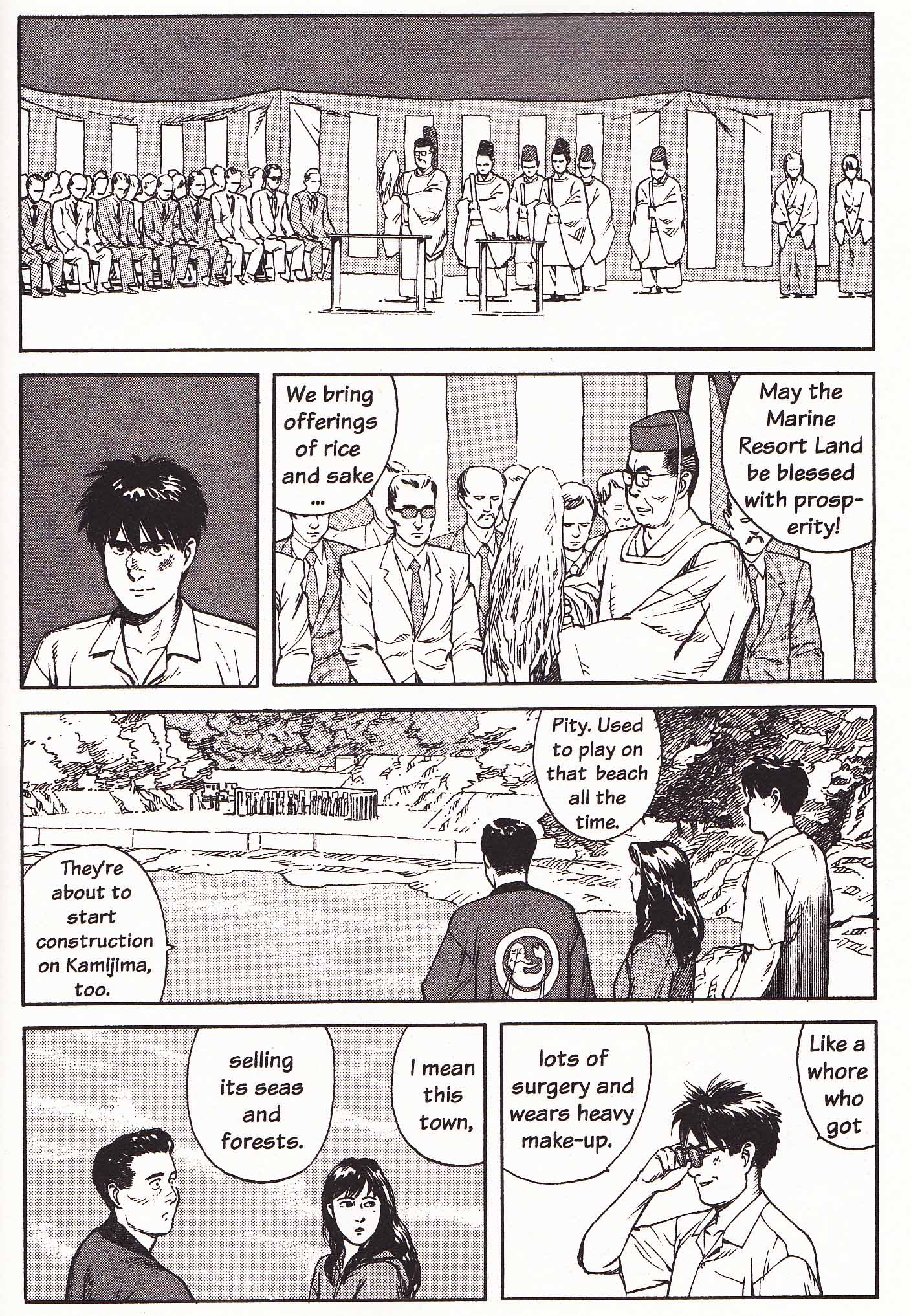

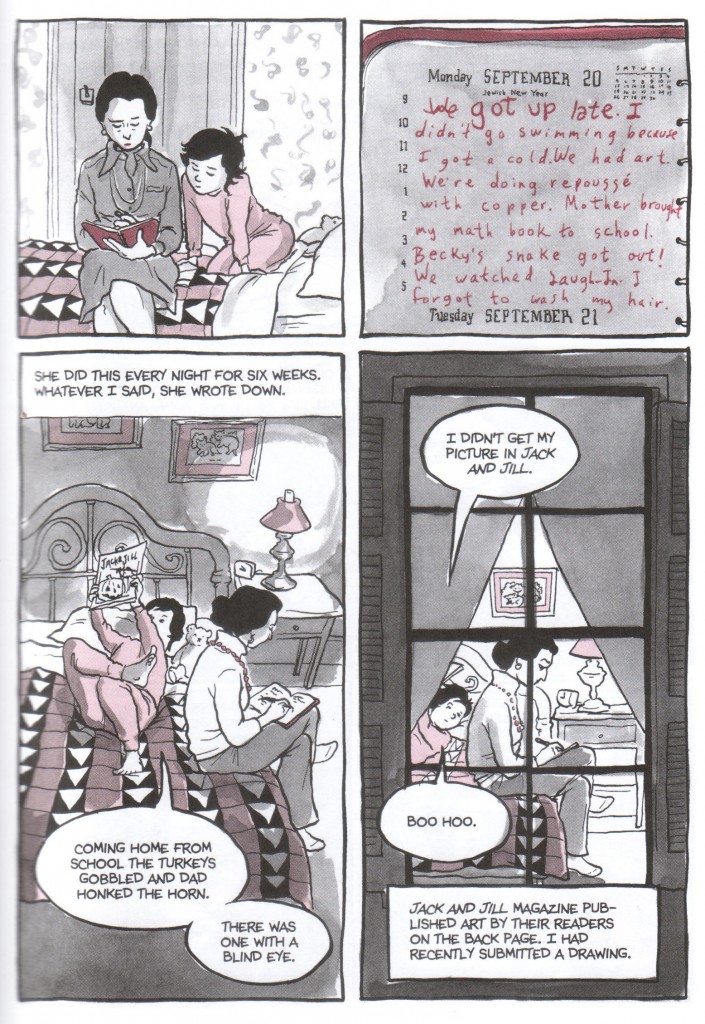

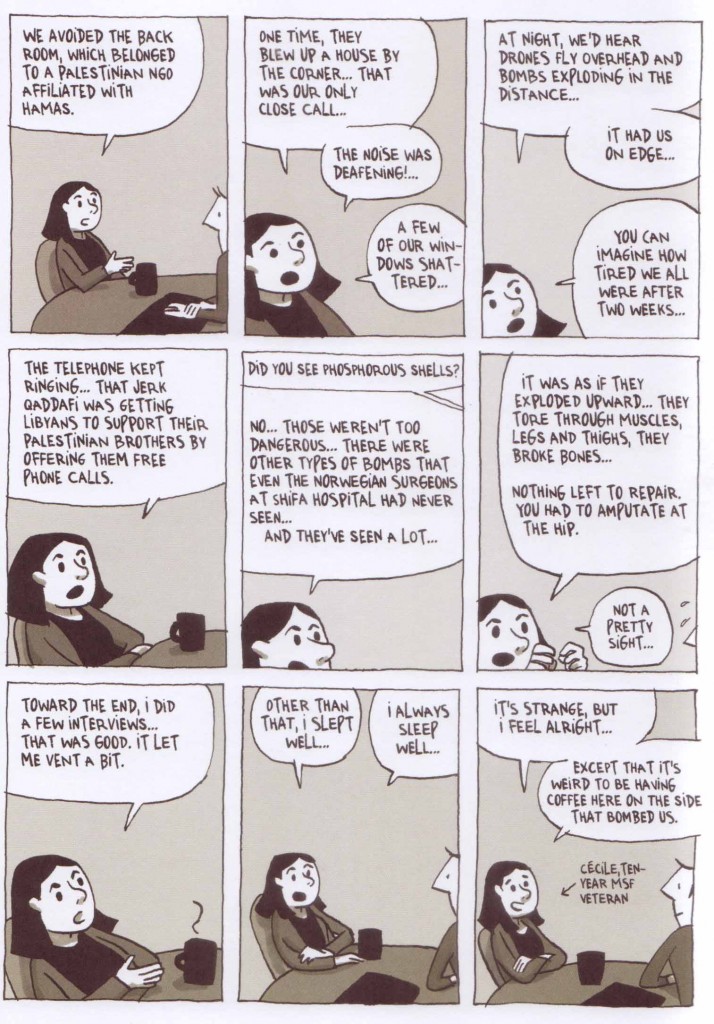

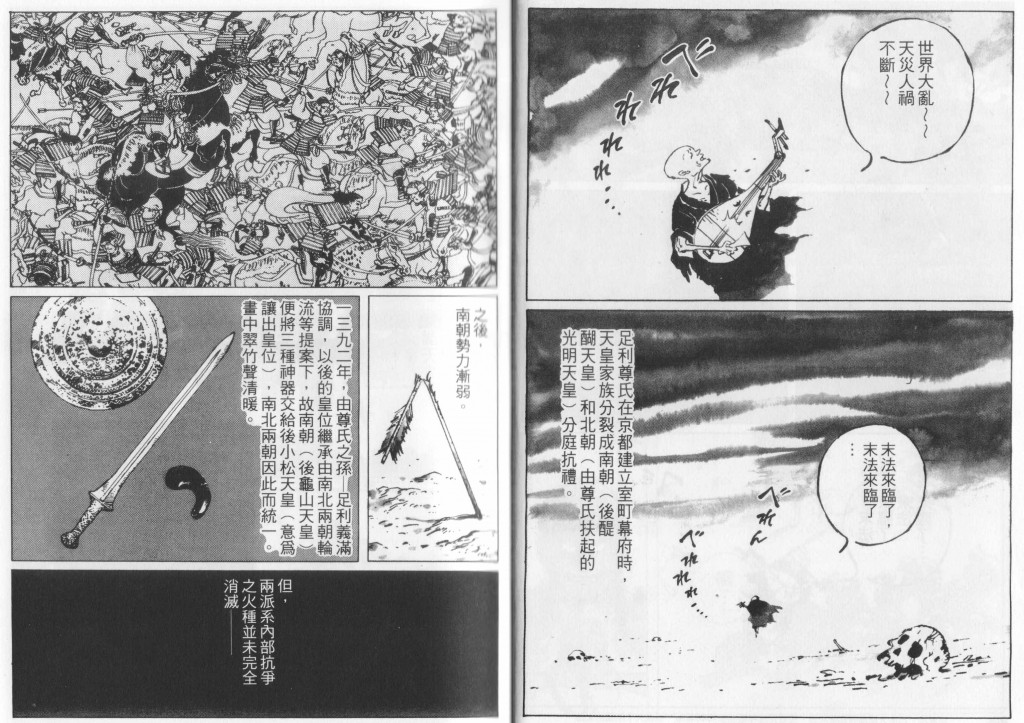

Yoshihiro Tatsumi is big in Singapore. Singaporean director Eric Khoo’s animated film, Tatsumi, premiered at Cannes and has a 100% “fresh” rating from 17 reviewers at Rotten Tomatoes. Meanwhile, with Drawn and Quarterly’s series of early Tatsumi gekiga having apparently stalled after three volumes covering 1969 to 1971, the Singapore-based Landmark Books has picked up the baton with the present work, which carries the translated Tatsumi oeuvre a little further, into the years 1972-3. It is a collection of nine stories that I much enjoyed reading, with an informative and perceptive introduction by Lim Cheng Tju and some teasingly brief notes on the stories by Tatsumi himself.

The themes will be familiar enough to readers of the three previous translated collections: the grinding poverty, greed, lust and cynicism seething just below the surface of urban life during Japan’s ‘economic miracle’ of the 1960s and ’70s. My only disagreement with Lim’s introduction is where he says “Compared to his earlier stories, this collection paints a much more pessimistic world.” I would argue that there is a consistently bleak outlook on modern life running through the entire Tatsumi oeuvre, at least as translated into English. This manga artist is noir to the bone.

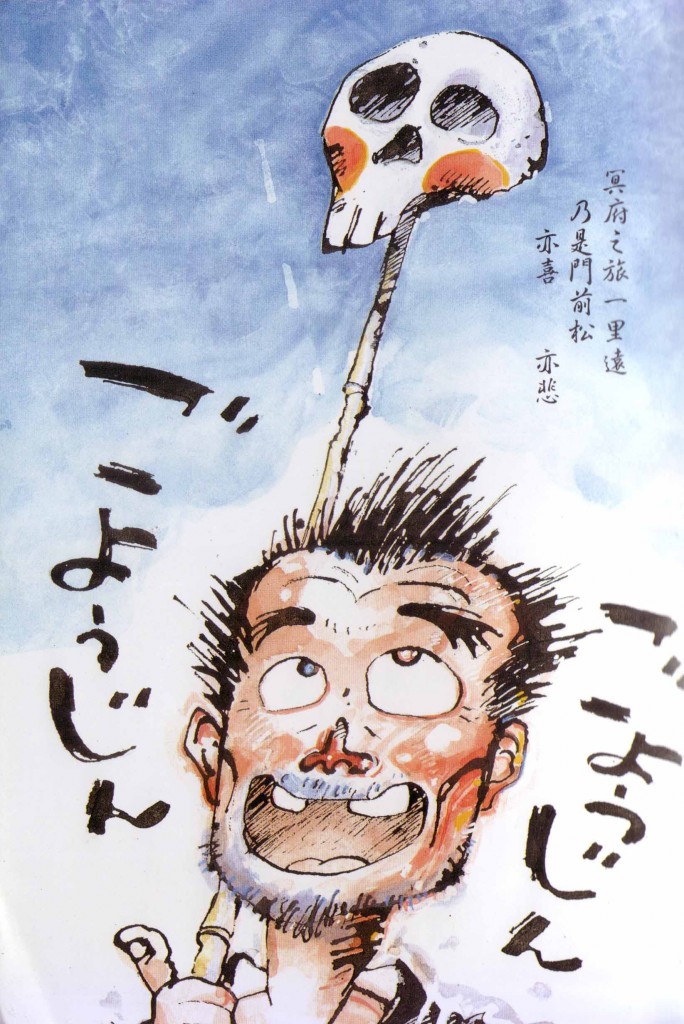

Critics may argue that there is something simplistic, gleefully ghoulish, even puerile about this collection and its relentless harping on the same nihilistic themes. Yet for me, it works. The way Tatsumi riffs on a series of crude symbolic themes is pleasurable in much the same way that scratching at an itchy insect bite is pleasurable. He scratches away at certain themes in modern (1970s) society that do, in fact, need a good scratch. And as his obsessions return again and again, they are reinforced and modified in interesting ways. Three recurring symbolic motifs, in particular, dominate the collection.

1. The running man

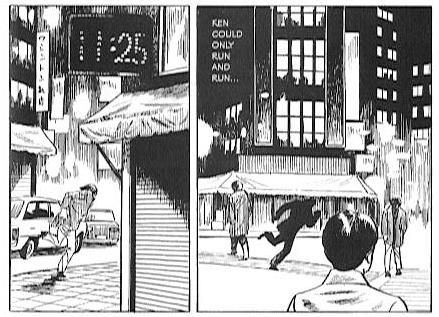

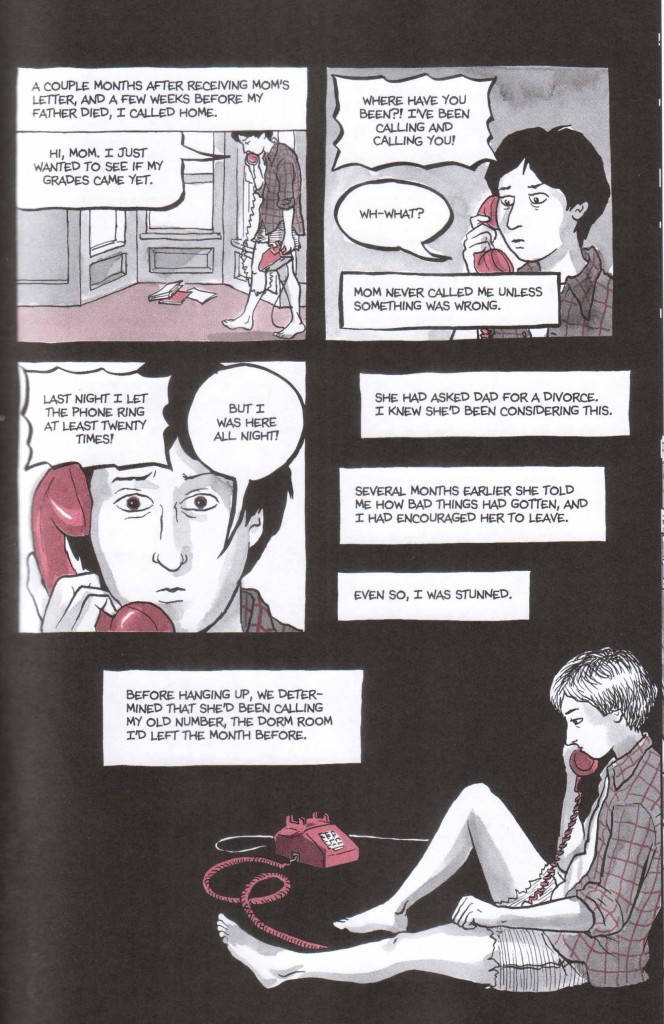

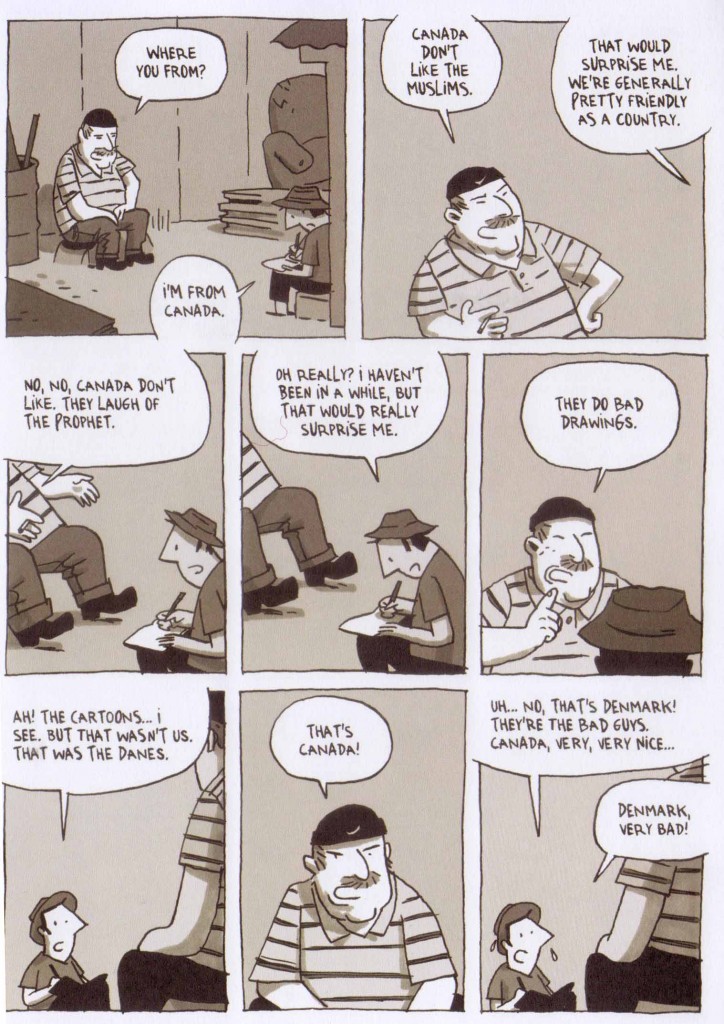

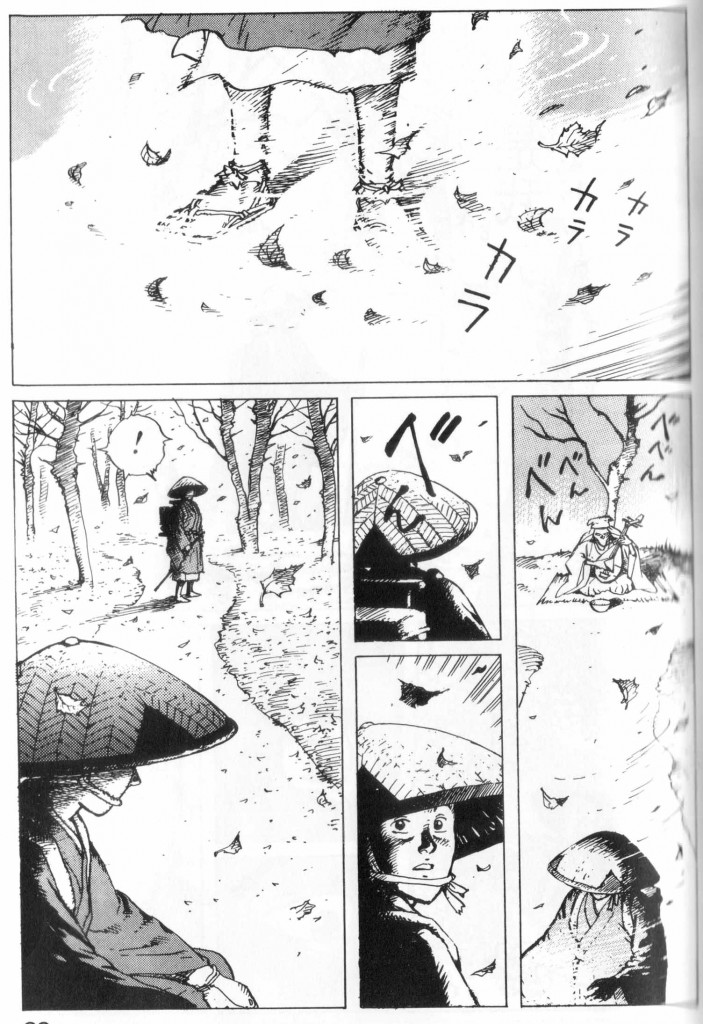

We find this in three of the nine stories. It is incidental in “The Lantern Angler” (p.198), but essential to two stories. The title story, “Midnight Fishermen,” focuses on two men who room together, Ken and Yasu. Ken makes his money as a gigolo, picking up women of a certain age who pay to have sex with him. Yasu is an atariya – a traditional marginal Japanese occupation, which entails deliberately getting hit by cars and then extracting money from the driver. Both men are social predators, but the atariya is an ambiguous figure, who victimizes by being a victim. The story ends with Yasu, who has finally made enough money to retire, buy a car and start farming in Hokkaido, unintentionally getting run down and killed by a hit-and-run driver, completing his transition from self-destructive predator to downright victim. Ken is deeply shocked and runs away. We see him in silhouette (p.32; fig.1), running past brightly-lit office buildings at half an hour to midnight, captioned “Ken could only run and run…” There is no movement in this frame; Ken is running, but it feels as if he is a floating piece of nothingness – antimatter, perhaps.

Fig.1: Midnight Fishermen

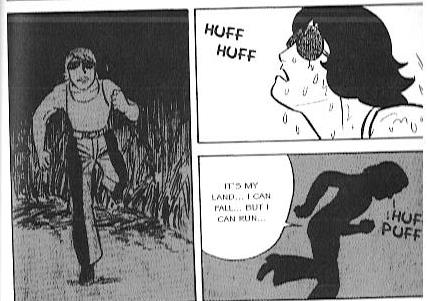

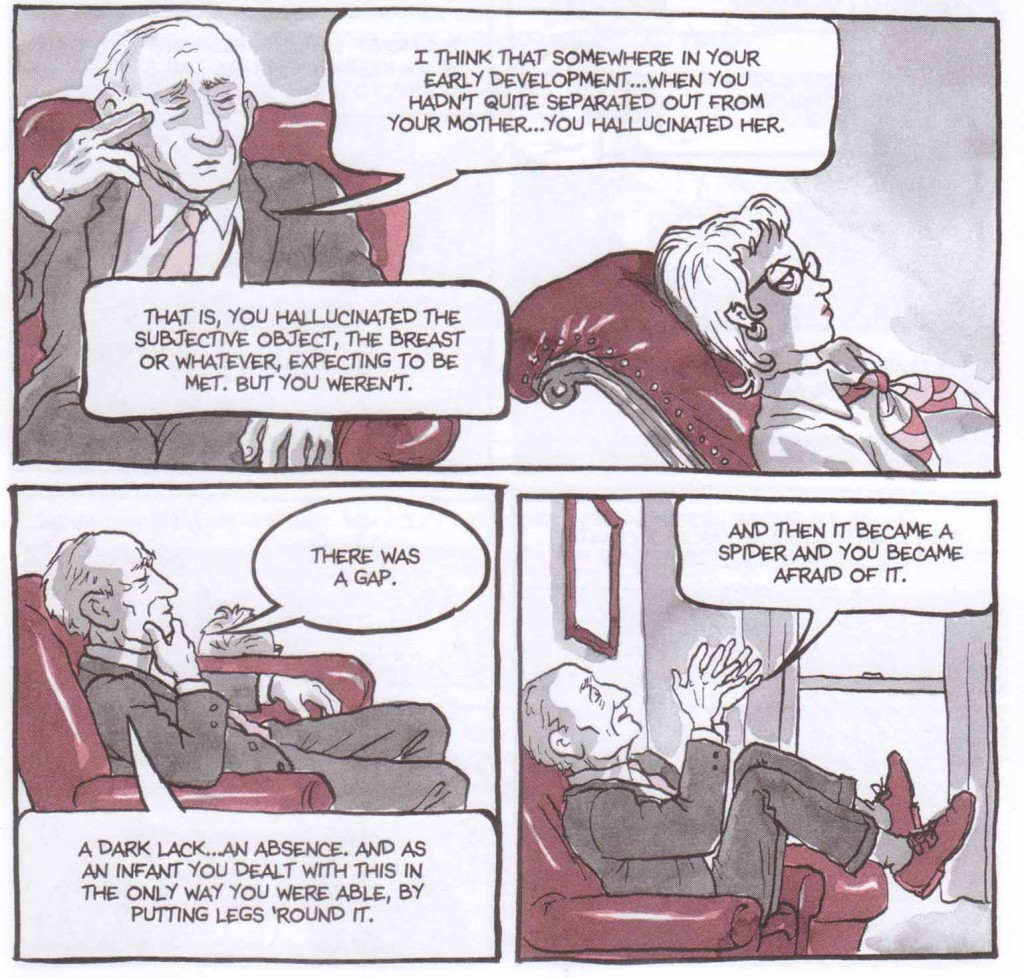

The running man theme returns in “Run with the Midnight Train.” In this story a man trapped in the relentless grind of daily urban life seeks escape by buying a plot of land in the country with borrowed money. It is essentially the same theme of rural escape as in Midnight Fishermen, except that this time our hero actually gets out to the country. There he apparently hopes to build a house and start a new life as a farmer. It is in a very remote district, taking a whole day for him and his girlfriend to get there from Tokyo, and she is far less enthusiastic about the whole idea, especially when he tries to have sex with her in the open field (p.80). Once they have arrived in the remote wilderness, it becomes clear that any new life will include separation from her. She loses patience and goes home, leaving our hero to run around the field saying to himself “It’s my land… I can fall but I can run…”The final frame freezes him as he runs through the night towards the reader (p. 86; fig. 2).

Fig. 2 Run With the Midnight Train

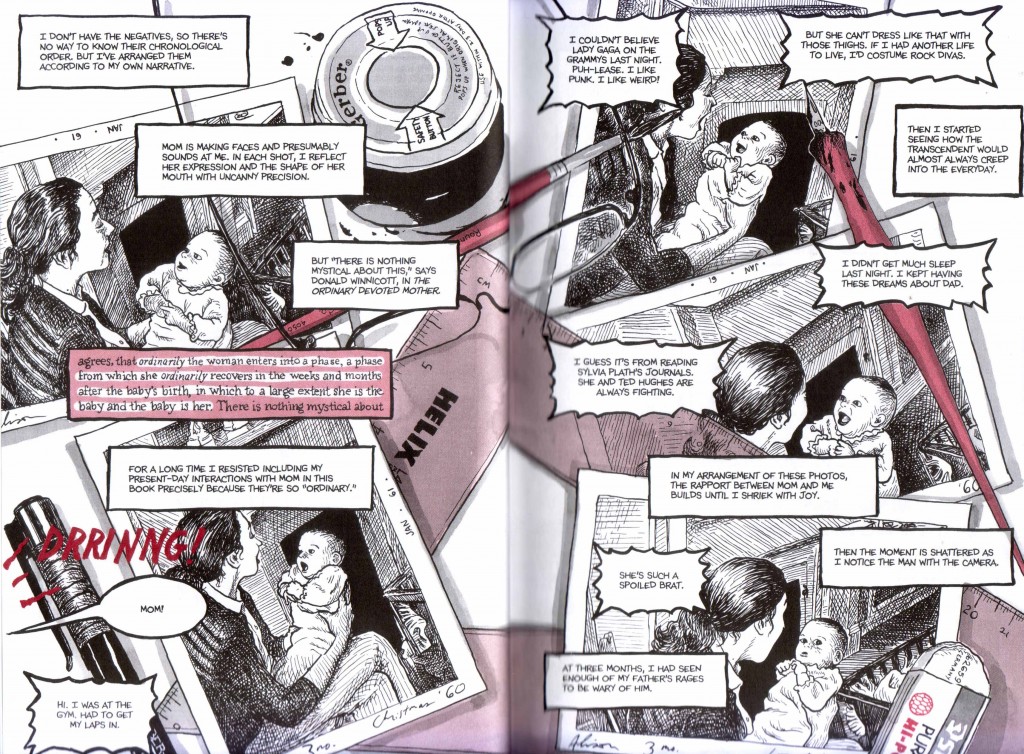

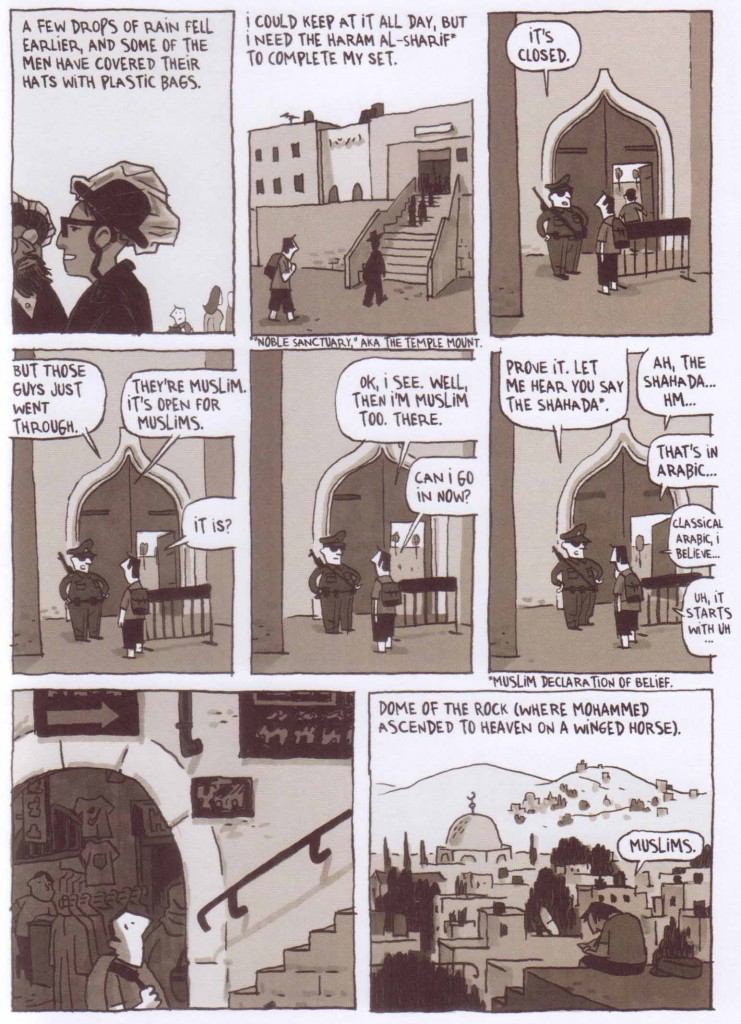

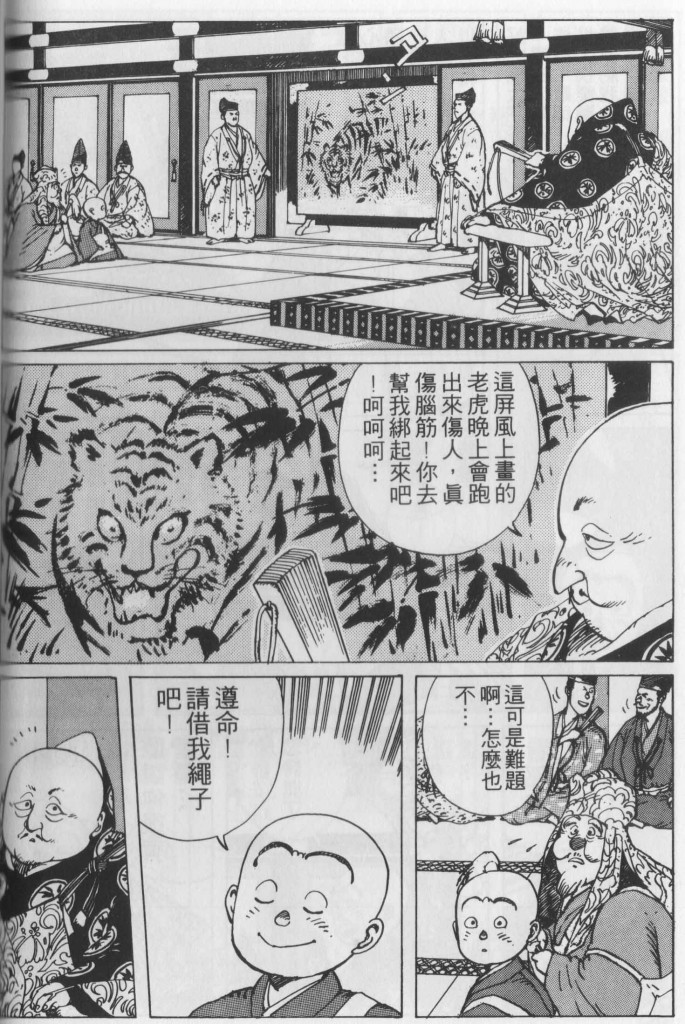

2. Physical and spiritual filth

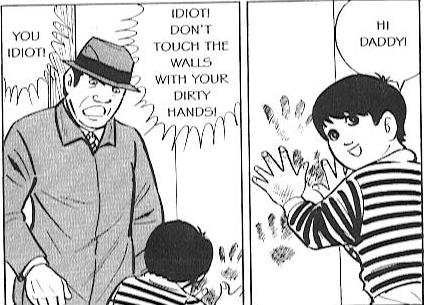

In “Welcome home daddy,” our hero is a prosperous middle-aged man with a dangerous gambling habit. He loses a fortune at a yakuza dice-house, only to win it all back with the final roll of the dice (p.48). Returning to the house he so nearly had to forfeit, and suffused with relief at his near miss, he finds his son touching the white wall in the lobby with grimy hands, leaving hand-prints. In the final frame, we see him screaming at the son for dirtying the walls (p.50; fig.3). It is a surprisingly discordant finale to a story that seemed to be flirting with a happy ending. Our hero may have got off the hook this time, but the spiritual filth has remained, and we sense that disaster has only been temporarily postponed.

Fig. 3 Welcome Home Daddy

In “The Dawn of Porn,” a struggling young manga artist – always a popular choice of protagonist – is given the keys to the penthouse apartment of a highly successful manga artist, to spend the night there with his girlfriend. The one restriction is that they are not to open the west-facing window. Of course, as in a thousand corny fairy tales, our hero cannot resist taking a peek. It turns out the window overlooks the lady’s outdoor section of a public bath house. He also discovers some pornographic photos and is clearly aroused. His girlfriend calls him to bed, but first he cannot resist a look through the forbidden window. As he opens it, a gust of wind fills the room with soot from the chimney of the furnace heating the bath house waters (p.65). It is an unconvincing yarn (sorry to carp, but in reality he would have looked through the glass without opening the window) with a conservative moral message. (He shouldn’t have been trying to peep at a bath house while his girlfriend was calling him to bed in a see-through frilly negligee!) After cleaning up the sullied penthouse, the couple go back to their squalid apartment to catch up on their sleep. Their neighbour, a pervert given to turning down his stereo to listen to their love-making, has to turn it up to drown out their snoring (p.68). It is a rare moment of comedy.

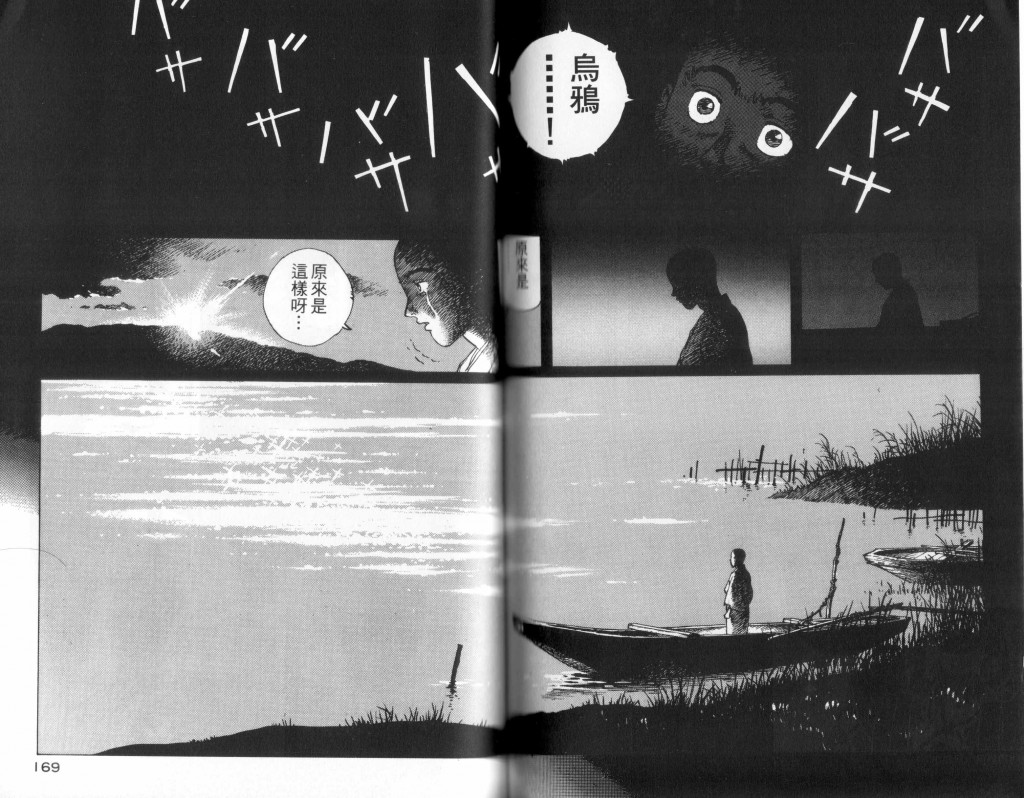

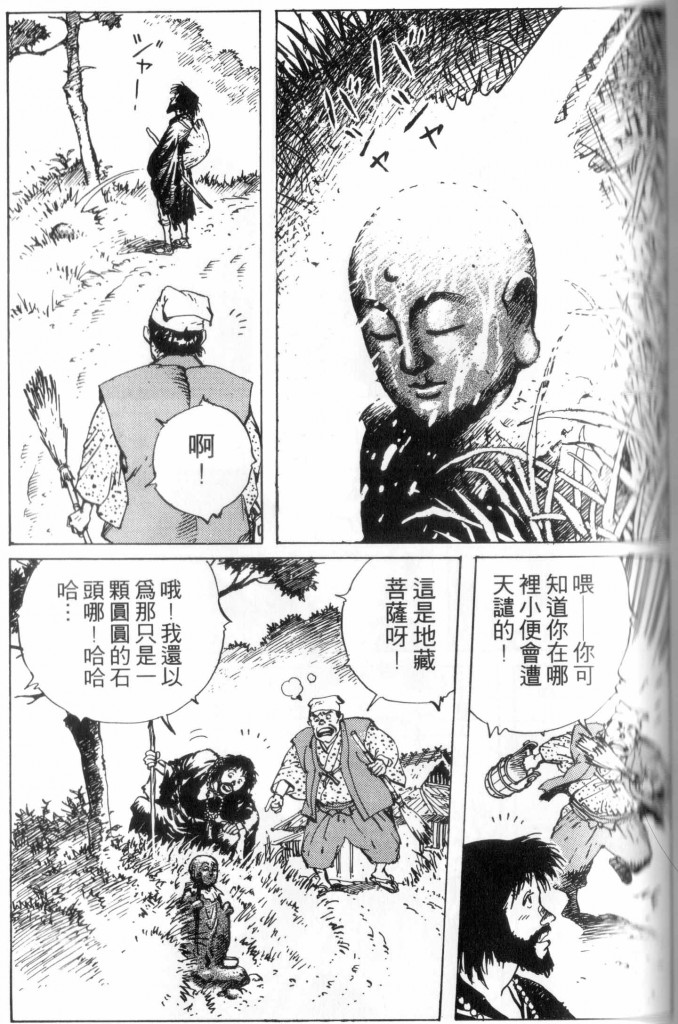

Fig. 4 Misappropriation

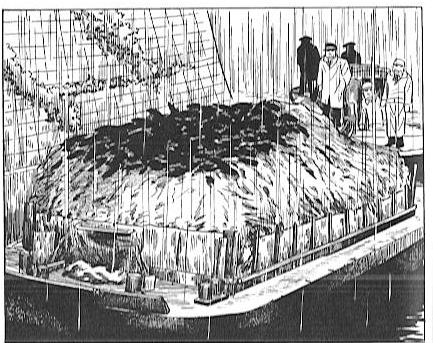

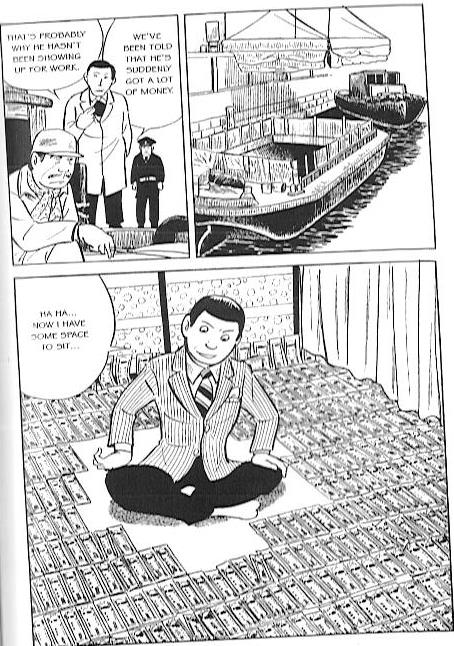

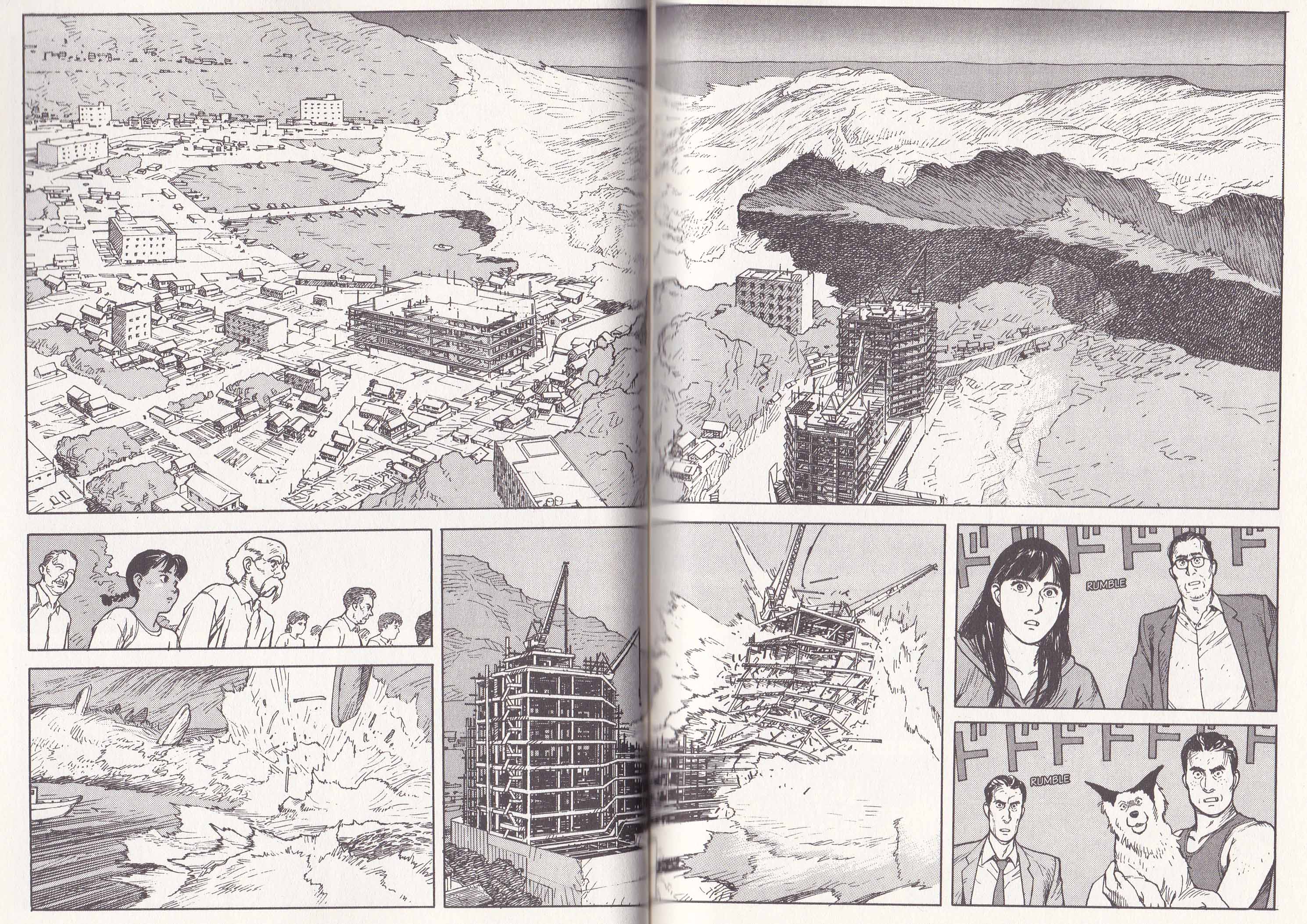

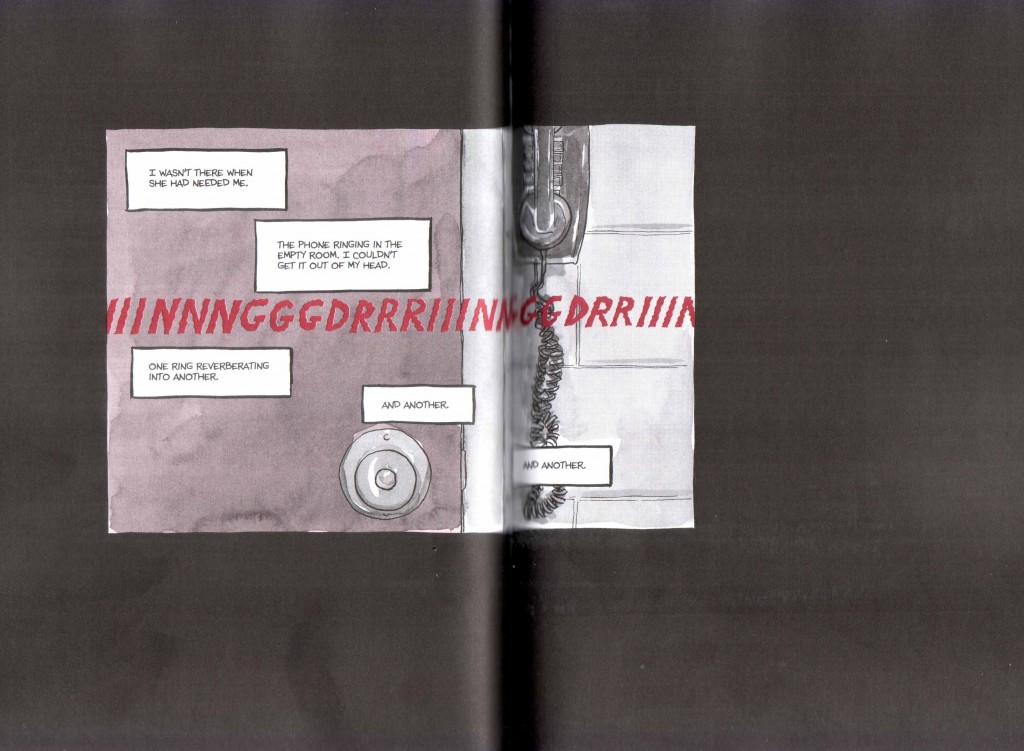

In a particularly brutal yarn, “Misappropriation,” the protagonist works on a barge carrying rubbish along the canal, following in a long tradition of Tatsumi protagonists working in sanitation. His boss resents the way people turn their noses up when the stinking barge floats by, although it is they who have created the rubbish. Indeed, he argues, they are the rubbish, cargoes of rubbish in the commuter trains that thunder over the bridge (p.156). Our hero gets a chance to escape when he finds five million yen in a paper bag someone has accidentally left in a telephone box. The next day a suicidal woman plunges to her death from the bridge, just missing the rubbish barge as she hits the water (p.168). It turns out she also had a baby boy, whose body is found atop the barge’s pile of rotting refuse, covered in a thick carpet of avaricious crows competing for meat (fig. 4). Our deeply-shocked hero runs away and starts a new life with his millions, buying an expensive suit and sleeping with a pretty bar hostess, but we know it will not last long. On the last page (p.174; fig. 5), the police are already investigating his disappearance amid rumors he has come into a lot of money, while, in a surprisingly subtle touch, the rubbish barges are shown floating at anchor, empty and clean. In the final frame, our hero is in his room, surrounded by a carpet of bank notes, sitting cross-legged in the space he has created by spending the first million. He comments, “ha ha… now I have some space to sit…” So recently hemmed in by poverty, now he is hemmed in by money. His avarice has doomed him, and he even welcomes the early inroads into his fortune because they give him some space to sit, to breathe.

Fig. 5 Misappropriation

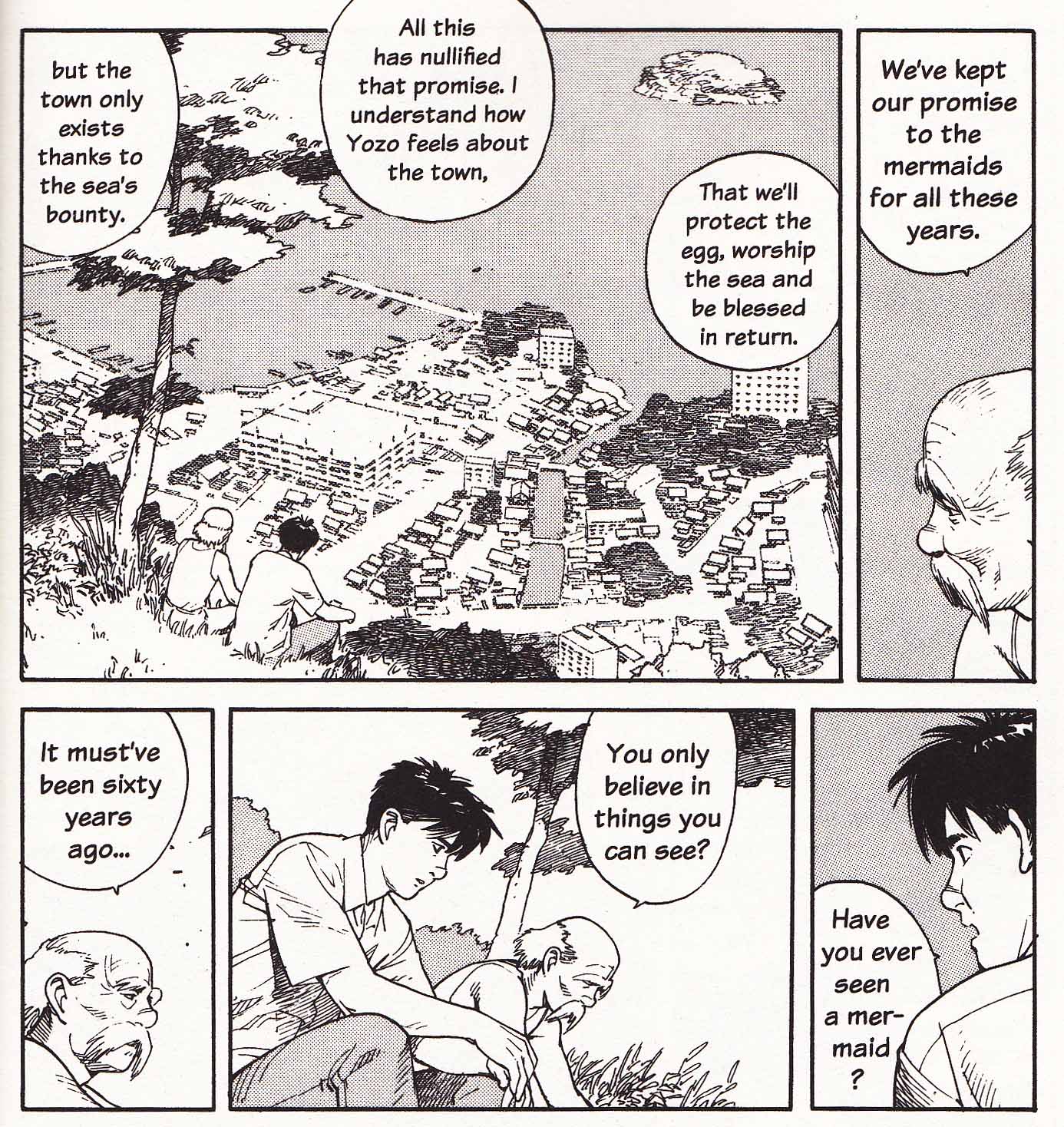

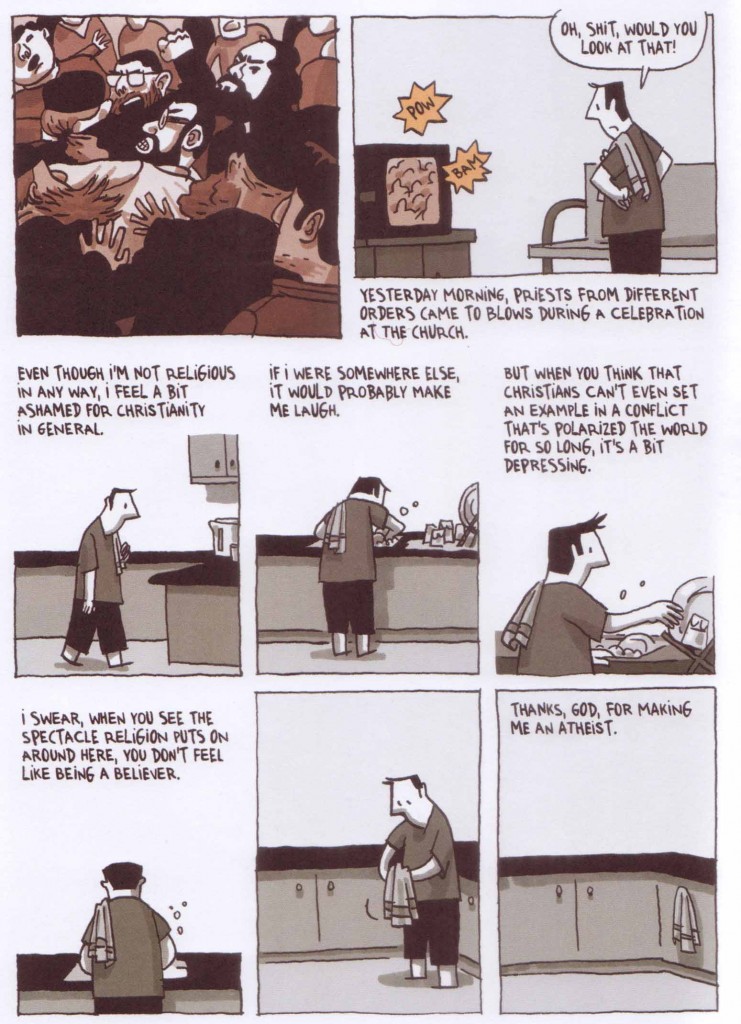

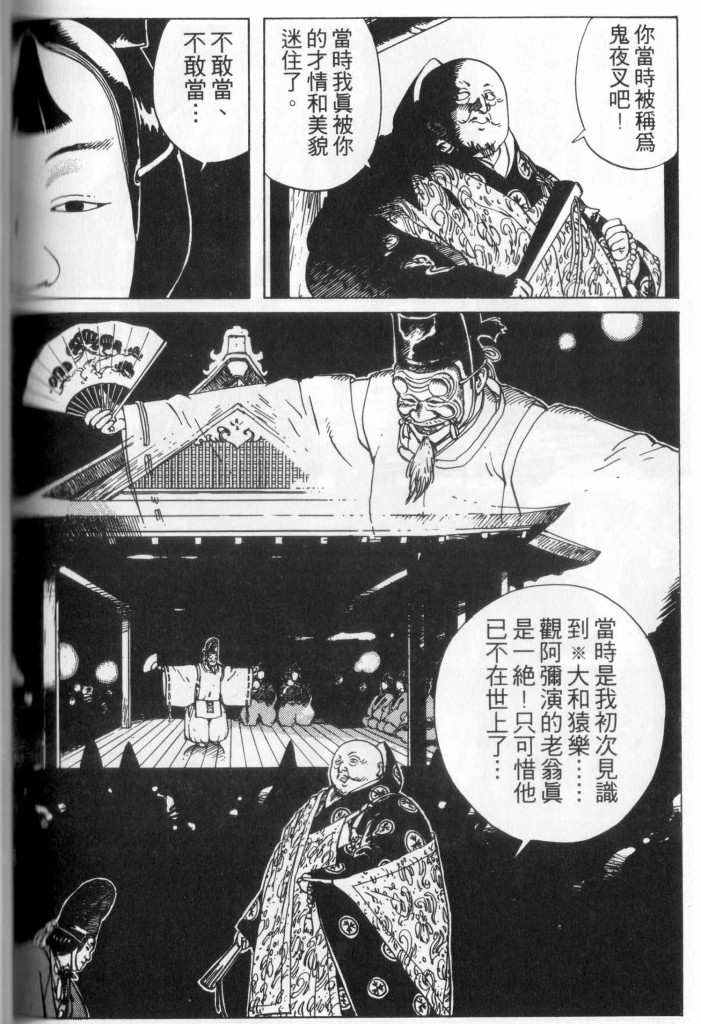

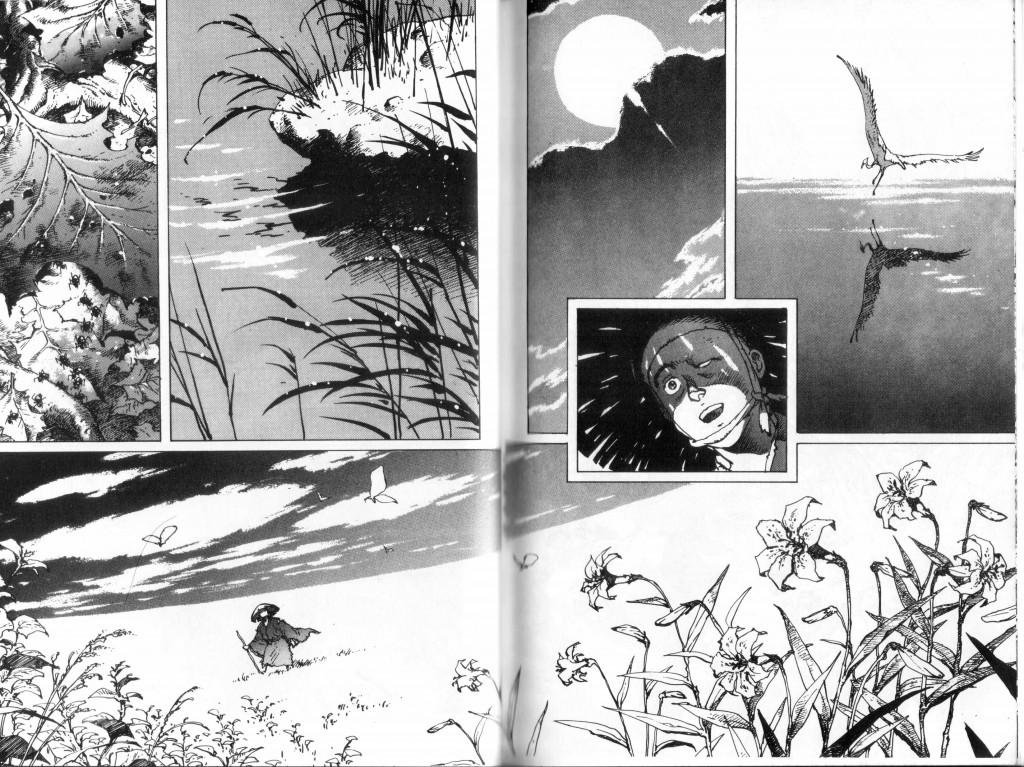

3. Fish and fishing

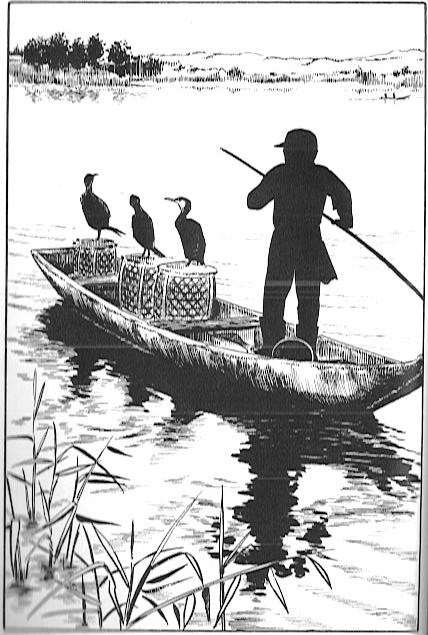

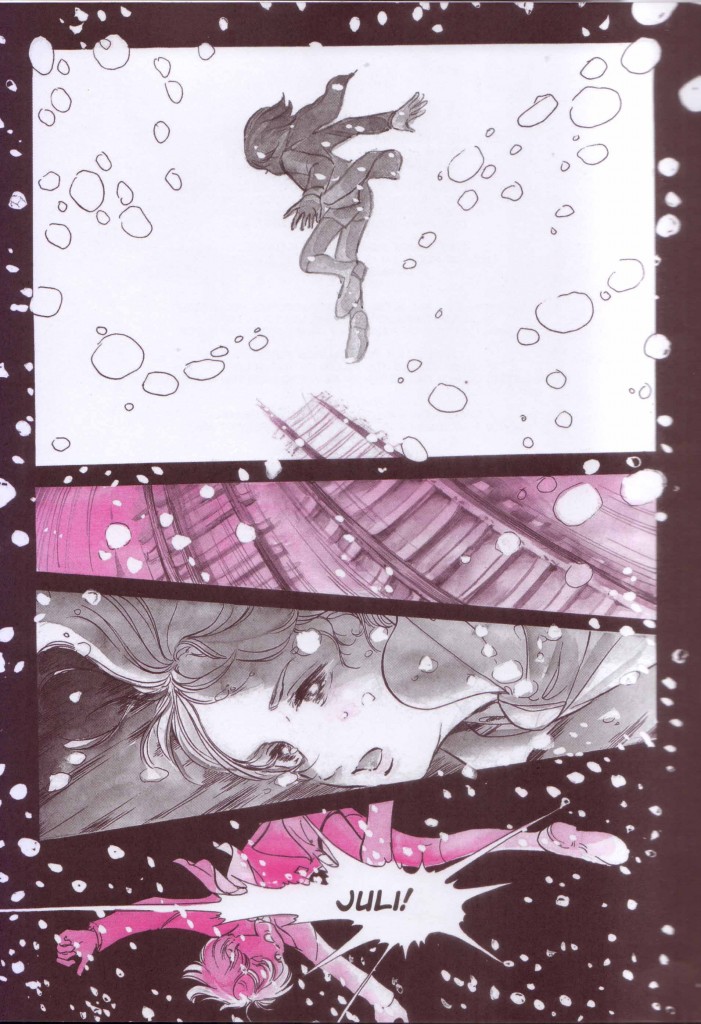

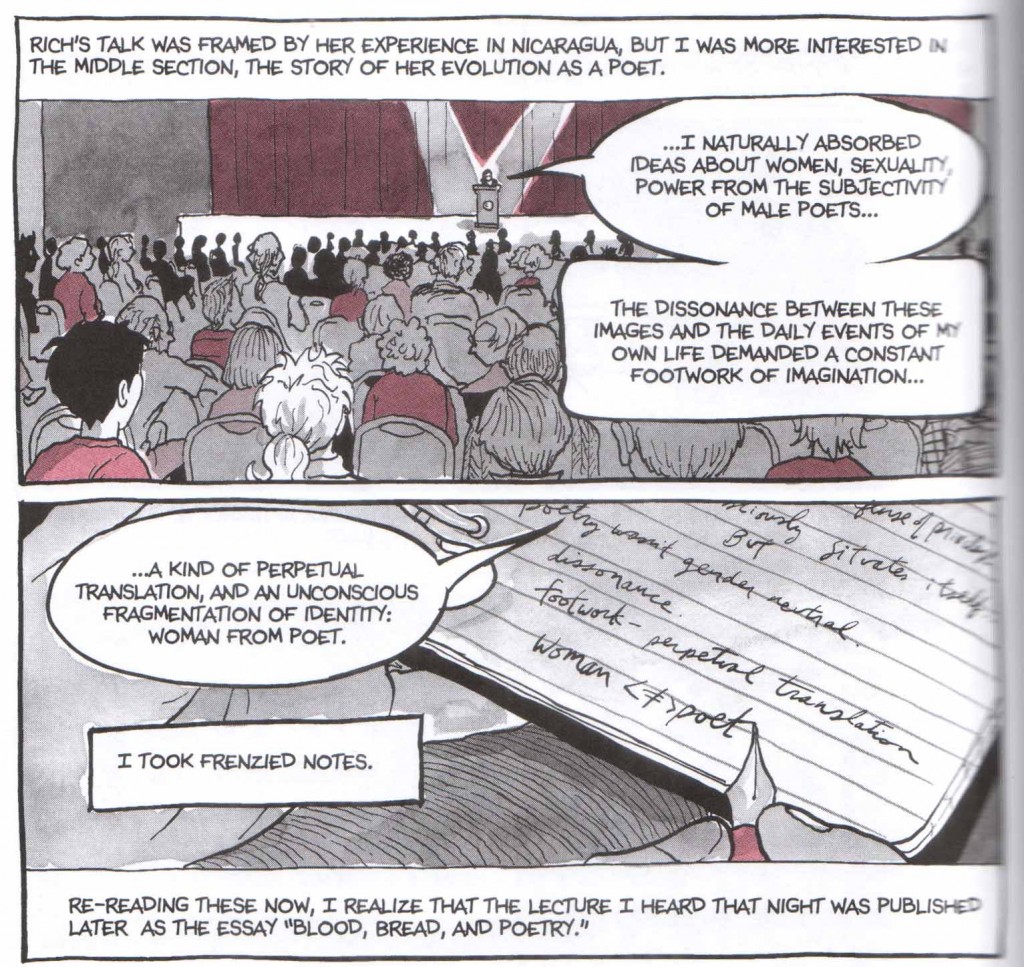

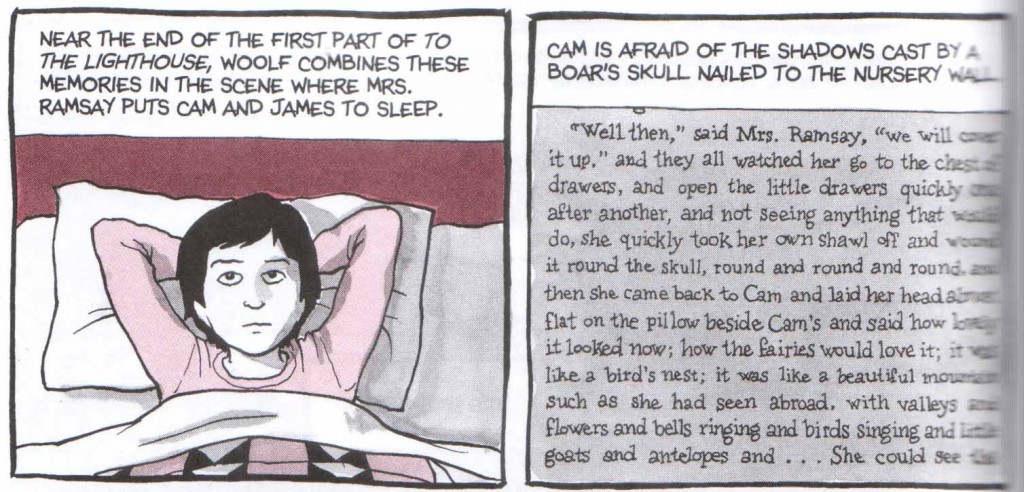

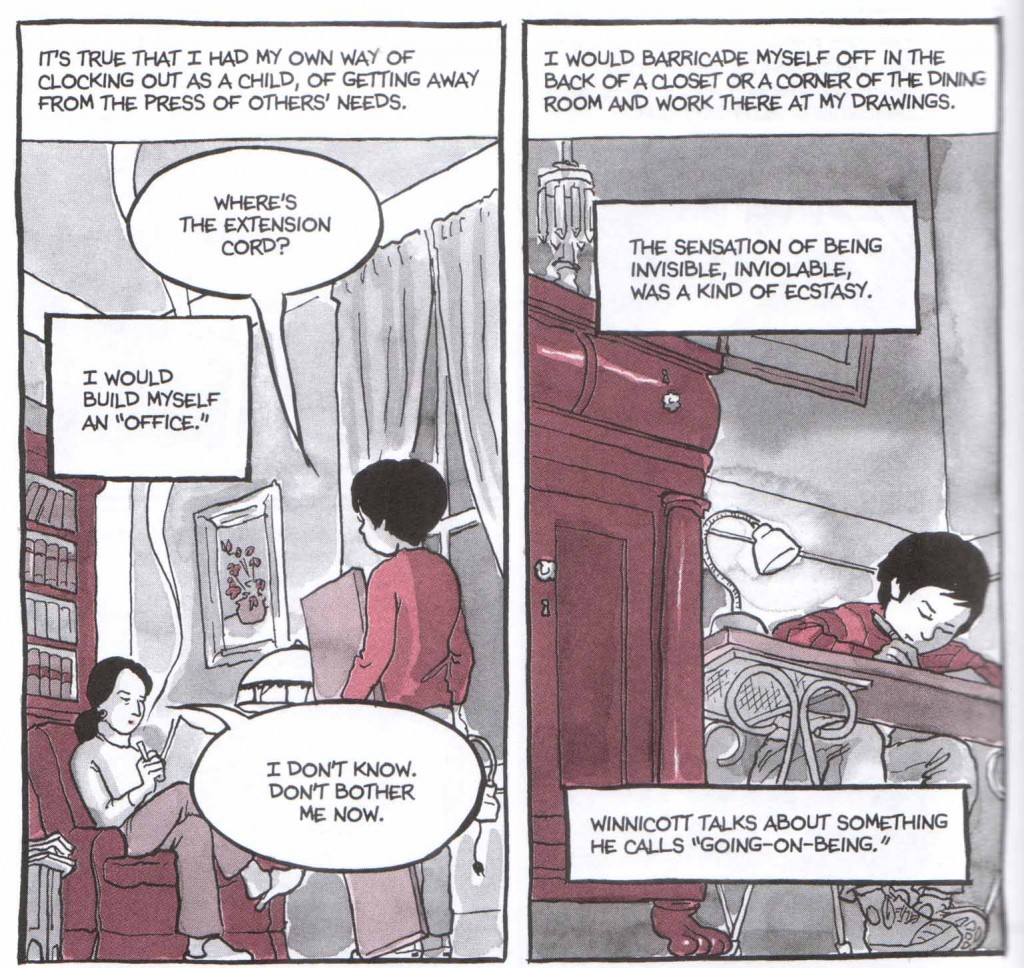

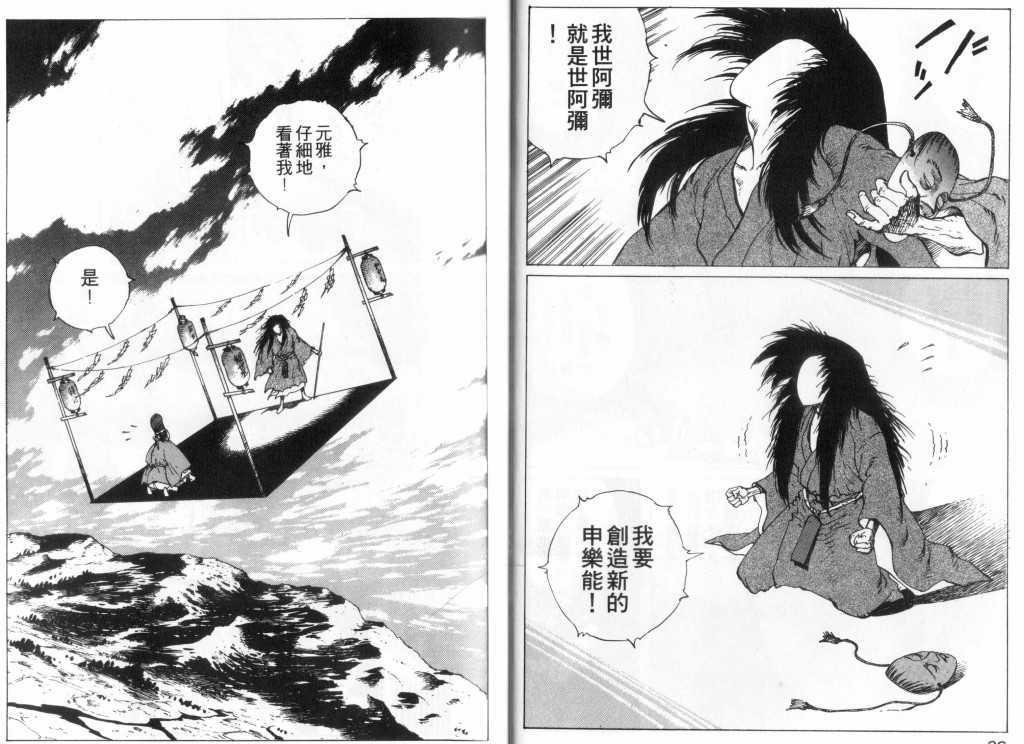

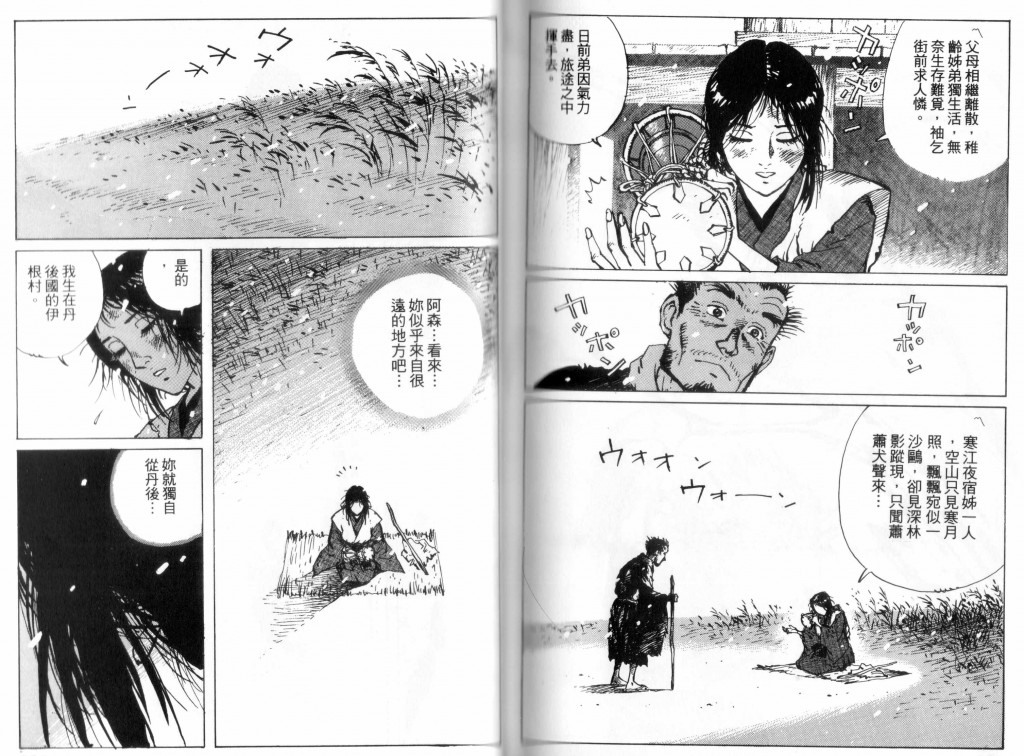

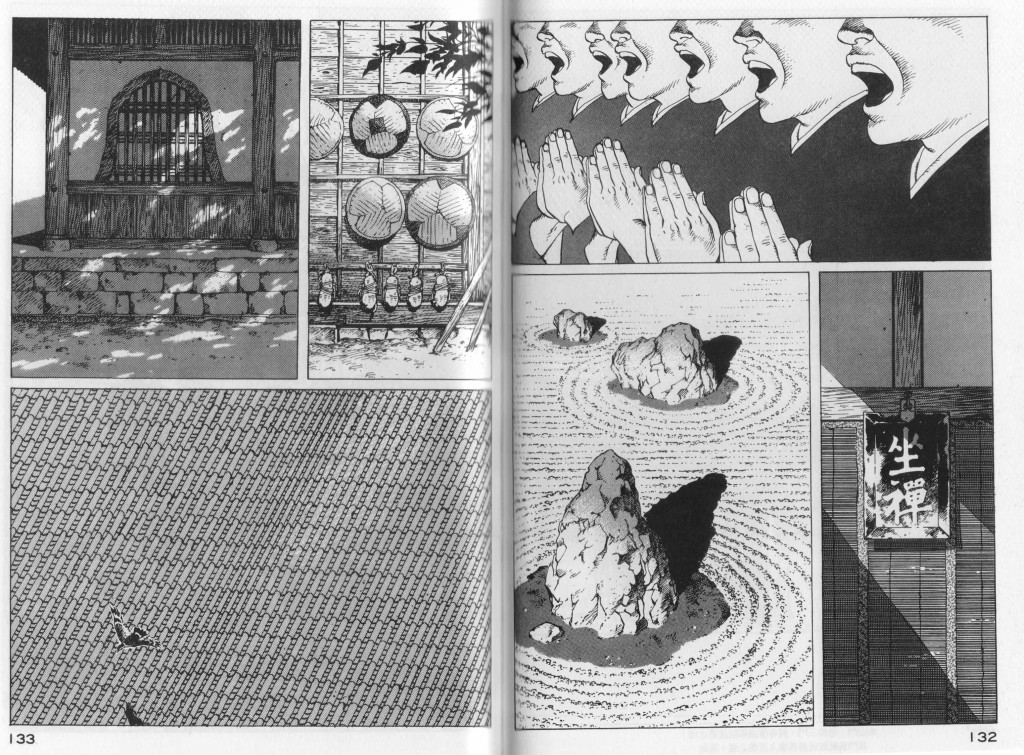

The title story clearly establishes fishing as a metaphor for amoral exploitation, in that case of women by the young gigolo. The theme returns in “Hometown,” the most interesting piece in the book. The protagonist, a young woman from a village on the Nagara river in rural Gifu prefecture, is now working as a prostitute in the red-light district of Yanagase in Gifu city. She returns to her hometown for a few days. Her brother has inherited the family cormorant-fishing business (p. 129; fig. 6), and is unmarried at thirty. As she says, in a wounding sexual insult, “you’re married to the cormorants!” (p.138).

Fig. 6 Hometown

The cormorants themselves, like the atariya in Midnight Fishermen, are an ambiguous symbol, exploiting and exploited. Always libidinous and hungry, they have a beady eye for the fish they prey upon, but can never swallow the fish because their owner has a string round their neck. The fisherman’s grip on the cormorant’s neck is echoed by his hand grasping the neck of a bottle of sake, and hints at violence inflicted on the woman by her recently deceased father when she was a little girl and when she was gang-raped six years before. A Proustian memory rush is triggered by her dropping a saké bottle (p.146), which recalls the bottle broken the night she was raped, as well as the bottles of sake she was sent out to buy at night by her alcoholic, abusive father (p.140).

At the end of the story we learn that this was no nostalgic trip home – she was there to have a discreet abortion away from the prying eyes of her friends back in Yanagase (p.150). The implication is that the earlier experience of rape has ruined her for life. The story ends with her returning to work, cigarette in mouth, glint in eye, ready to resume her cormorant-like, exploitative/exploited existence in the fleshpots of Yanagase (p.151).

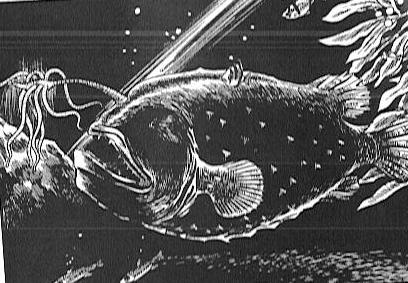

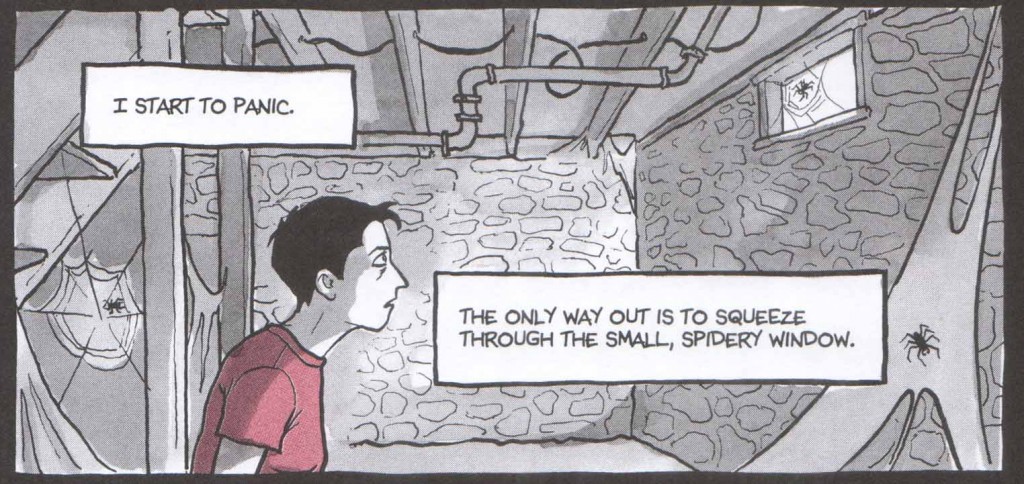

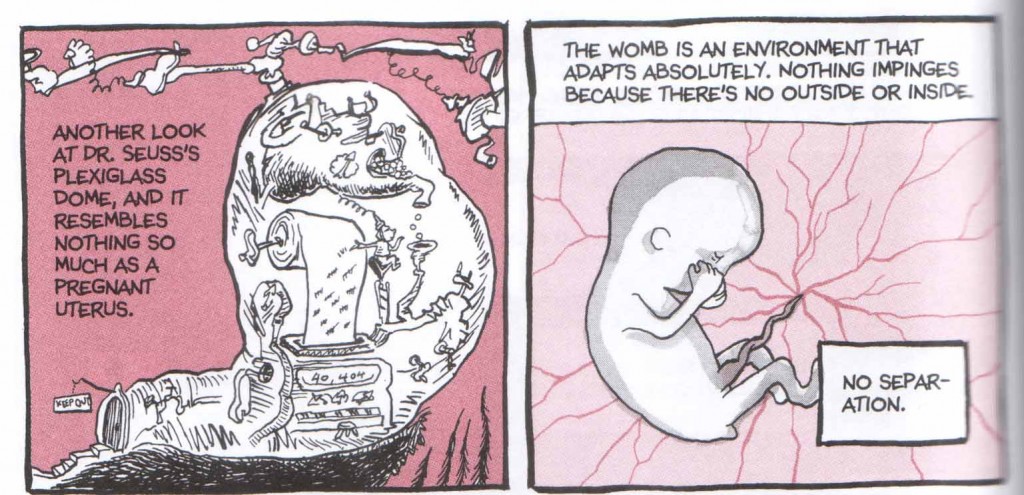

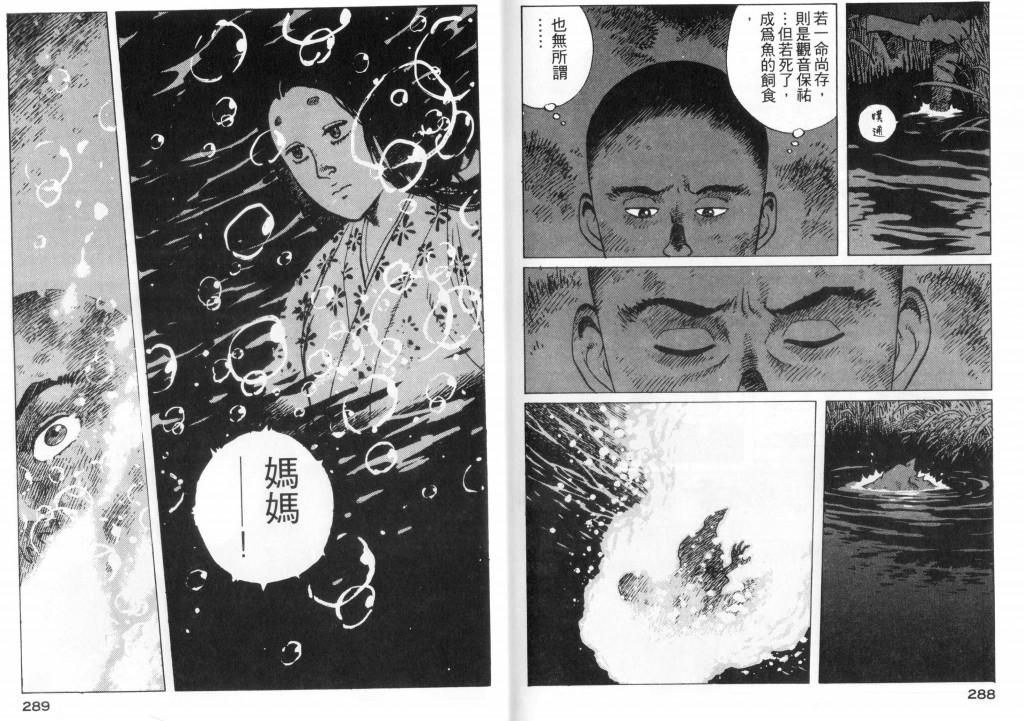

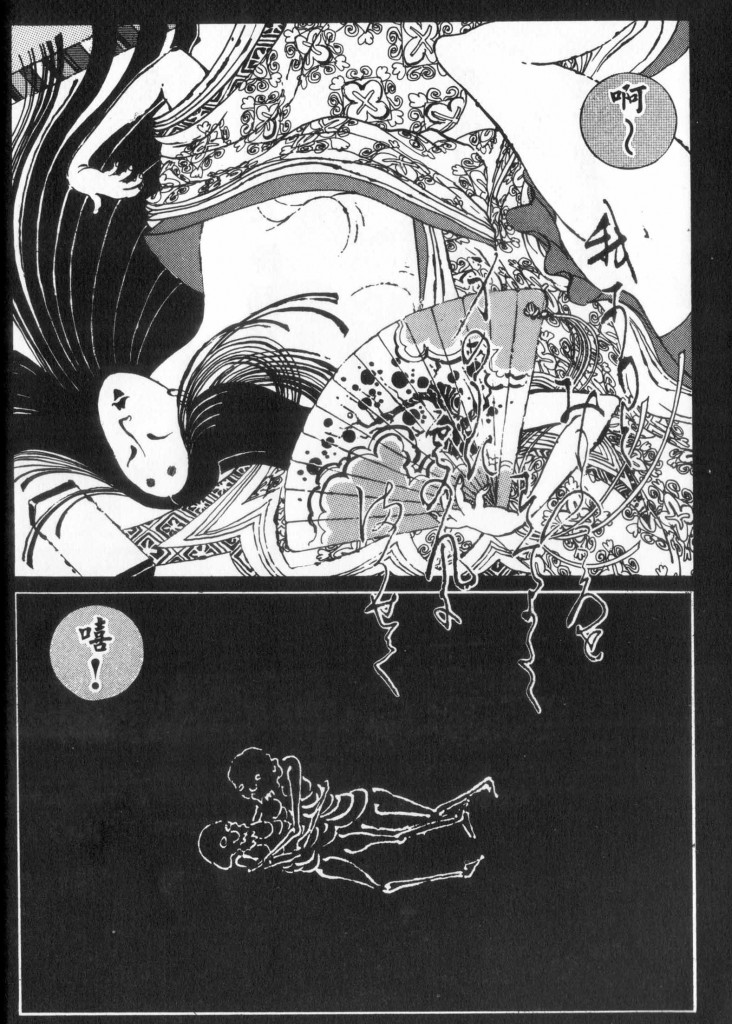

Fig. 7 The Lantern Angler

The aquatic motif returns in the final story, “The Lantern Angler.” In a highly implausible ménage à trois, a waif-like young girl lost in the big city is given shelter by a young man who is already shacked up with a coarse, fat girlfriend in a cheap apartment. One day the three of them go to an aquarium, where they see an angler-fish (p. 191; fig. 7). Our hero, a fish-fancier with a fish-tank in his apartment, through which we observe some of the interior scenes, explains that an angler-fish “lures small fish with that fluttery thing sticking out in front of its face and then gulps them up,” which immediately prompts his girlfriend to compare the fish to himself – he too waits in dark places to prey on smaller fish – in this case, the young girl he has picked up. It is a heavy-handed metaphorical cue; nor is there anything very original about the conceit; see my earlier “Reply to comment on Nishibeta article, Jan 27, 2012” for a discussion on the use of sea life, including angler-fish, as metaphors for life in general and low-class urban life in particular.

The identification between man and fish is rubbed in still harder when the young girl’s wealthy father sends a man to take her home to the island of Shikoku, and our hero accompanies her in the bullet train, hoping to marry her and thinking to himself “I might be able to float to the bright surface from the dark depths” (194). Dark frames, showing tropical fish against water expressed in jet-black ink, are interspersed with the narrative to really hammer the point home.

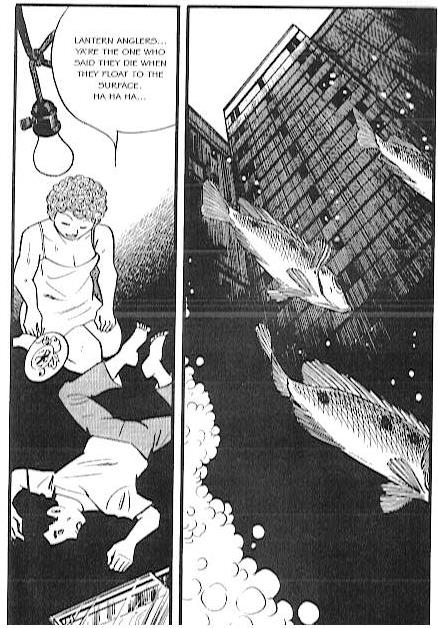

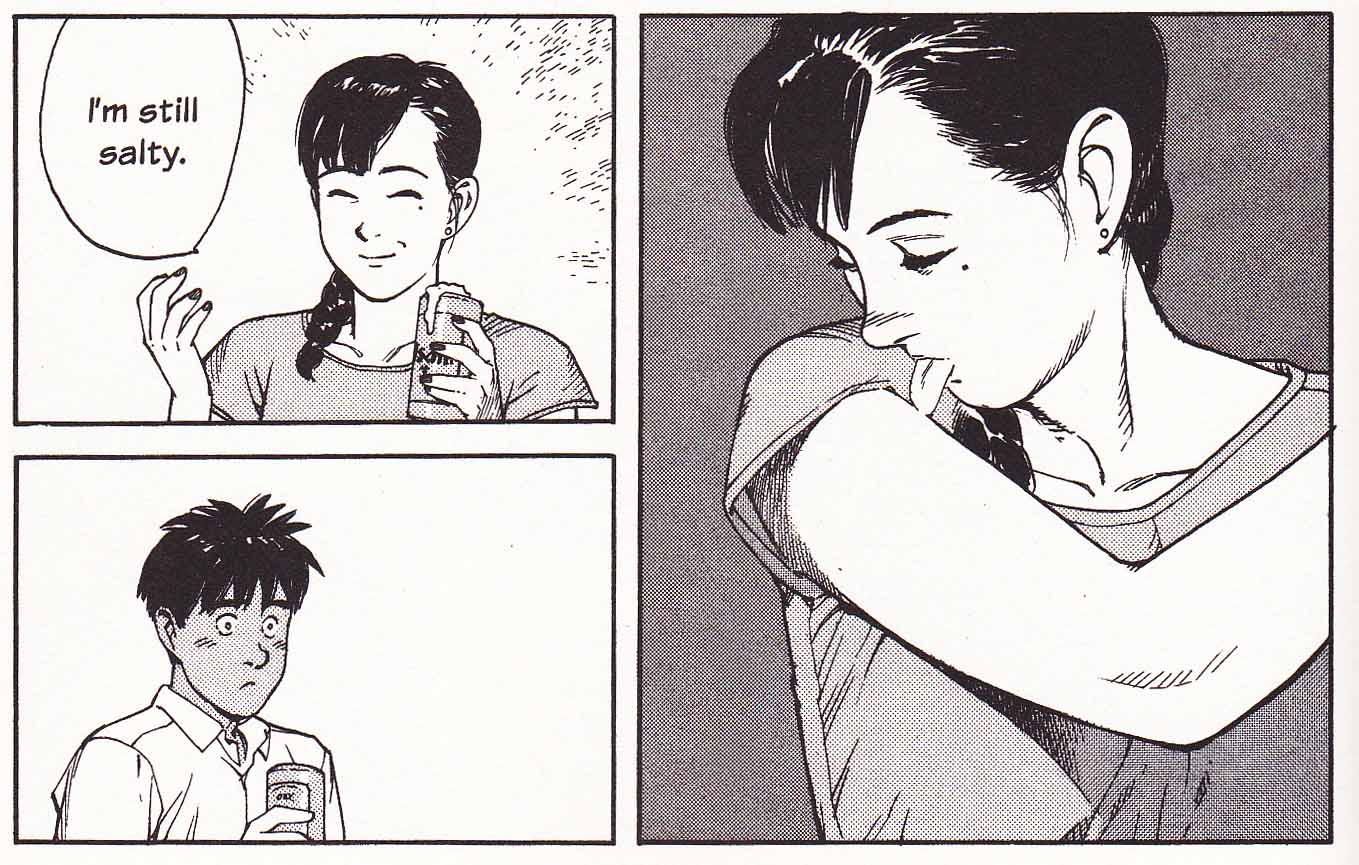

The young girl’s father turns out to be a murderous yakuza boss; the young man barely escapes with his life; he runs away (p.198) and in the final frame (p.200; fig. 8) he is back in his squalid apartment with his coarse, tubby girlfriend, collapsed on the floor while she waves a paper fan over him and echoes another of his earlier comments about angler-fish: “You’re the one who said they die when they float to the surface. Ha ha ha…” Thus the seemingly crude symbolism of the angler-fish turns out to have at least a second layer: like the cormorants in “Homecoming,” the angler-fish is a predator that is nonetheless trapped in its own environment. The same goes for the protagonist of this story, which is saved from banality by a richer use of symbol that we expect, and by the visual power of its imagery: the simple device of depicting water as black creates a gloomy submarine world into which even the most cynical reader is drawn.

Fig. 8 The Lantern Angler

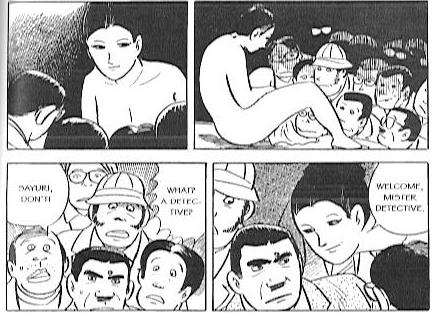

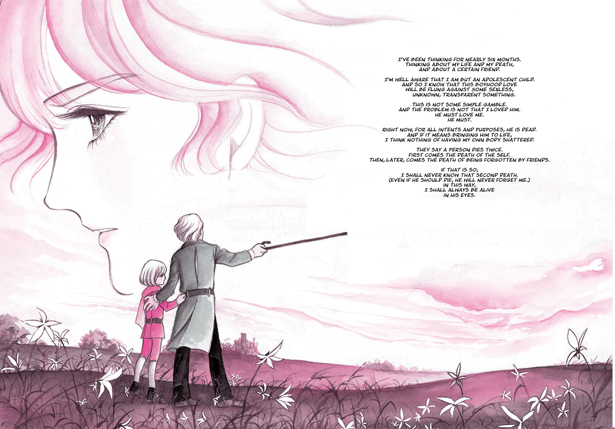

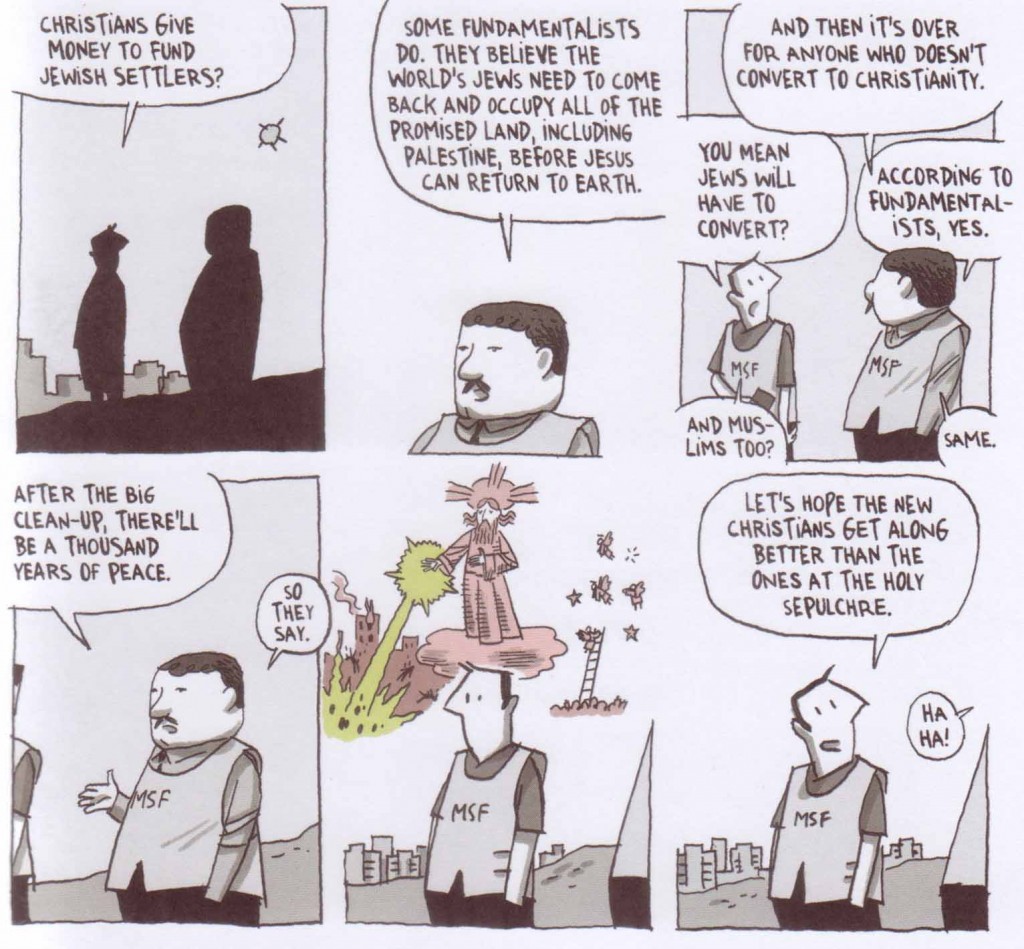

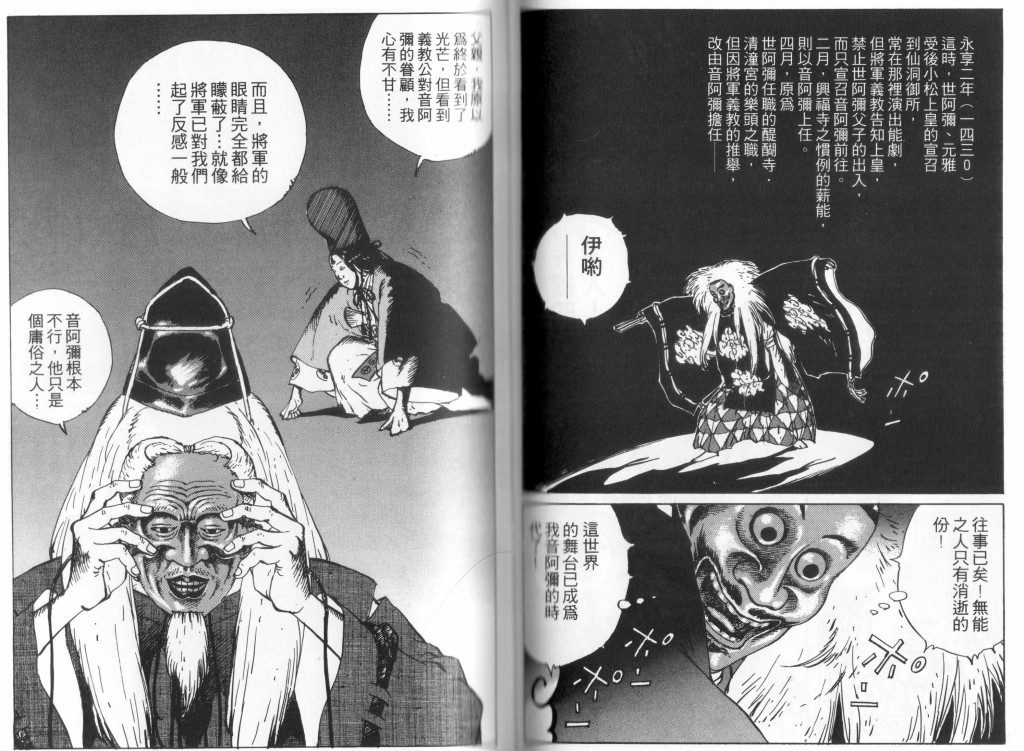

These three symbolic systems dominate the book. Together they present a brutal, Darwinian struggle for survival, in which the weak will always be defeated – caught and exploited, tossed out with the rubbish, or forced to run away. Only once is disgust and pessimism interestingly modified – in a seamy yarn, “My Boobs”, which deals with the relationship between a stripper called Sayuri and a couple of her devoted fans. It is the only story that is not commented on by Tatsumi in the preface, and may come from a slightly different phase in Tatsumi’s development.

In truth the story is more concerned with an even more private part of the female anatomy. Sayuri is twice arrested for showing it to her fans despite knowing there are plainclothes police in the theatre, and this is depicted as self-sacrifice, not dirty in any sense. As she opens her legs for the last time, she says “I was from an orphanage… yet all of you have loved me for what I am…” (p.103). The fans are driven to tears when she is escorted to a police car with a new-born baby in her arms. “She shared those boobs… we have to give them back to her baby now,” reflects one fan, in a slightly clunky think-bubble..

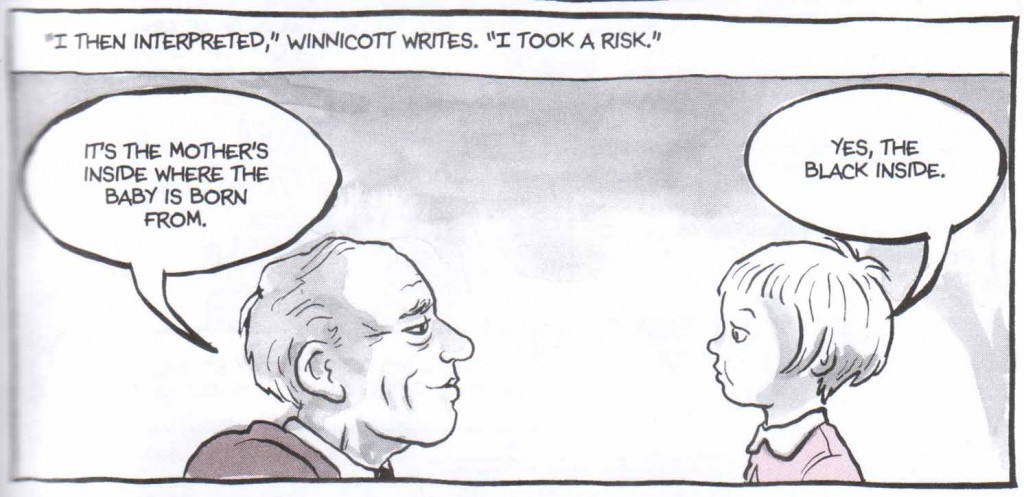

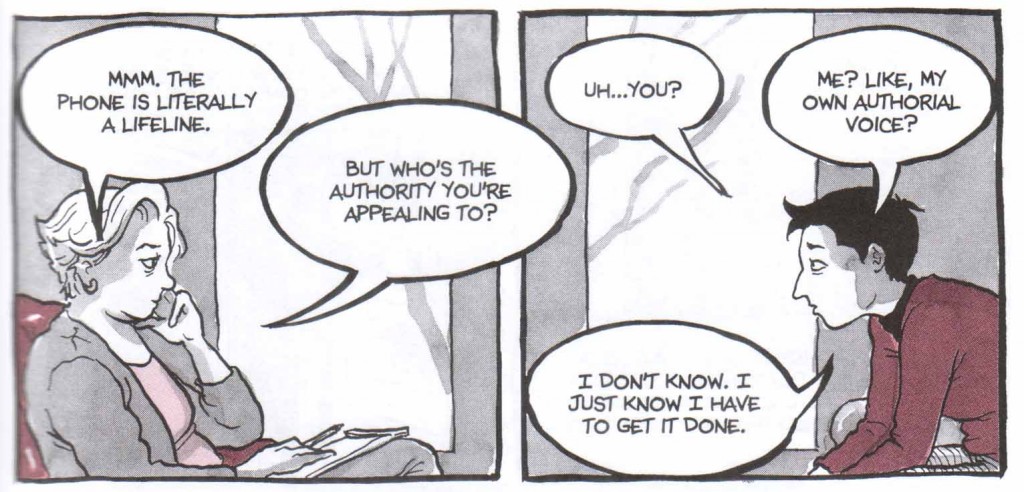

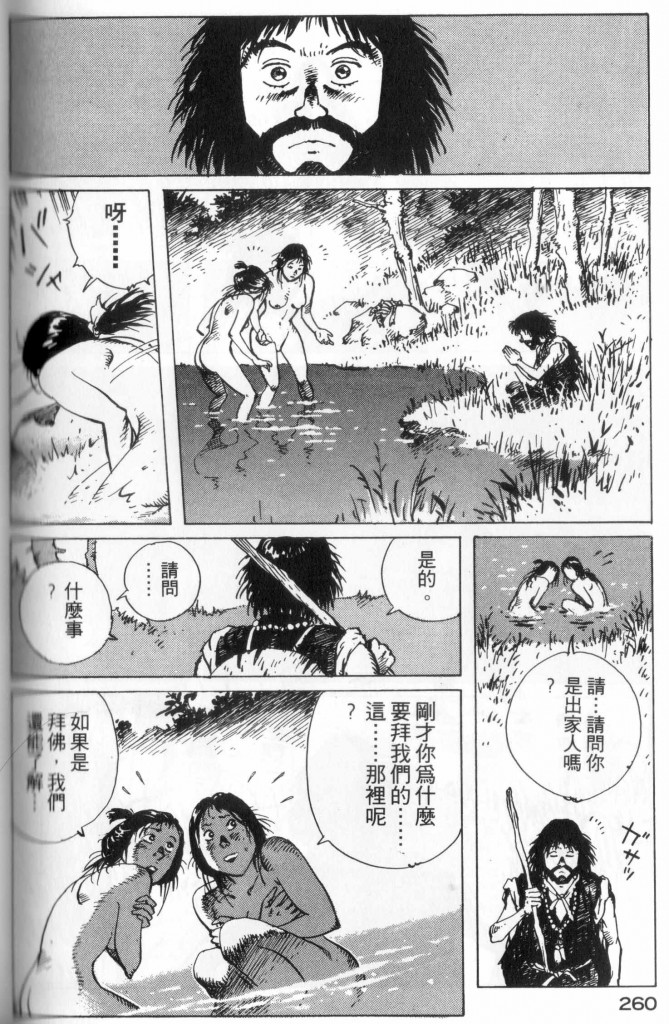

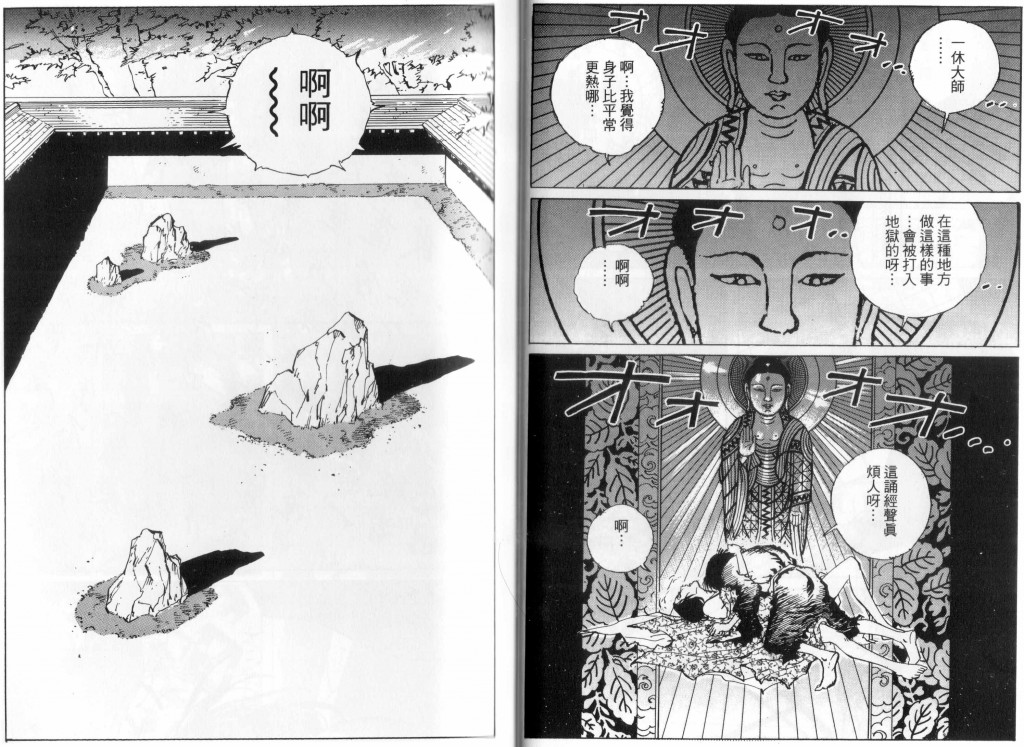

Amid all the wickedness and exploitation, Tatsumi finds love and purity of spirit in the most unexpected of places. For once cynicism and disgust give way to sentimentalism bordering on reverence. As Sayuri displays herself to the spellbound men, there is an apparent reference to Buddhist iconography and images of Kannon, the bodhisattva of compassion, usually depicted as female (p.102; fig 9). Note her steady gaze and the fact that she has mysteriously become much larger than the men staring at her. She then shows that like Kannon she has compassion for all men, graciously greeting the police detective who she knows if going to arrest her after the show.

Fig. 9 My Boobs

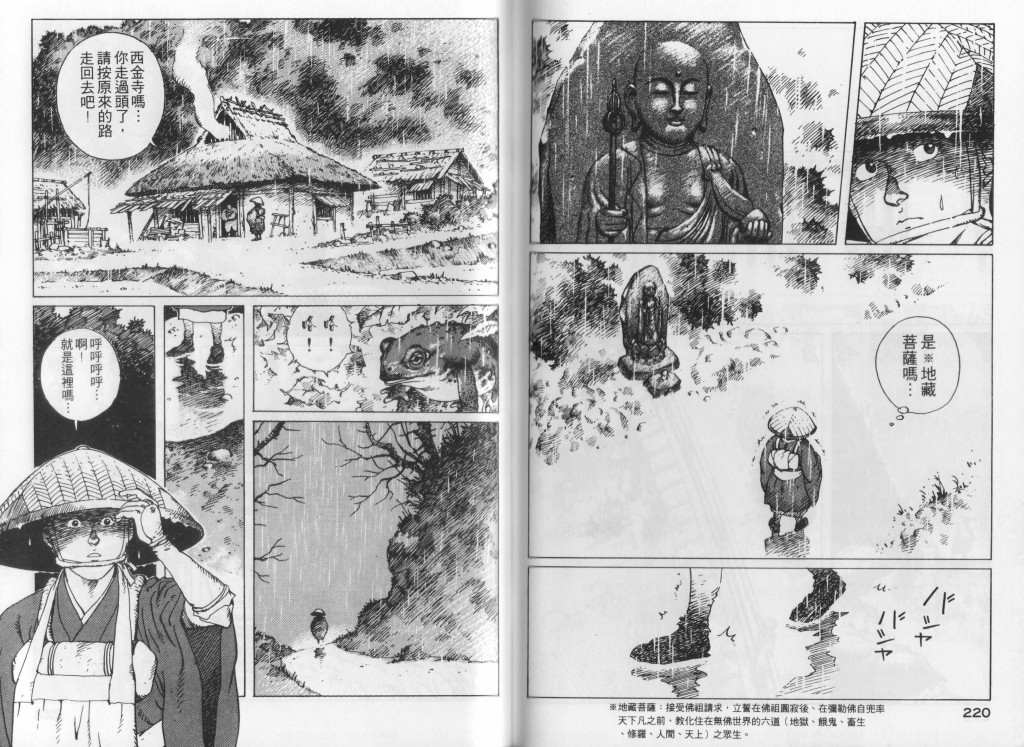

Landmark Books have done an excellent job of bringing these 40-year-old artefacts to life for the English-reading audience. Admittedly the translation is occasionally wobbly – especially in rendering Japanese onomatopoeia, a notoriously difficult task – and it is a slight pity that the title has been misprinted on the flyleaf. Still, the book succeeds in taking us back to urban Japan, c.1972-3. Unlike the three Drawn & Quarterly volumes, this one has retained the Japanese page layout, so that the book opens on the left rather than the right, and the pages run in the opposite direction to a conventional English-language book. I approve, but would remind readers that frame order also follows the principle of top to bottom followed by right to left. Since the English-language text in the bubbles runs left to right, it can occasionally be slightly confusing.

Those who hated the earlier Tatsumi volumes will hate this one too. Those who enjoyed the previous works will find that despite some very familiar themes and characters, there is an increase in sophistication, noticeable in slightly cleverer imagery, more dynamic artwork and the occasional unpredictable dénouement. I look forward to seeing something from 1974.

This book is not easy to come by – I cannot find it at any on-line book-seller except the Singapore branch of Kinokuniya, where it is priced at 19.80 Singapore dollars.

____

Tom Gill is professor of social anthropology at the Faculty of International Studies, Meiji Gakuin University