‘Show, don’t tell’ the saying goes, and that’s what Clowes does here. Ghost World, as those who’ve been reading along are aware, is the story of two teenaged girls fresh from highschool named Enid and Rebecca. Ghost World chronicles some episodic interludes in their relationship and Enid’s life.

With its purposefully ugly art, limited color schemes, Satanists, cafe settings, music references, and f-bombs, this comic is painfully edgy. The whole thing might as well scream: I’m new! Different! Hip!

And maybe the art is, maybe the setting is, but honestly I don’t really care. The story is pathetically old school.

Clowes depicts the two girls, Enid and Rebecca, as being shallow shallow shallow. They lead boring, directionless lives. They like to make prank calls. They pick on each other. Enid, in particular, is full of loathing towards others. When Rebecca challenges her to name one guy she finds attractive and would sleep with she says, wait for it!

David Clowes.

No, really, she does. Self-insert Mary Sue-ism! Ewww.

It’s one thing to show a set of characters as essentially problematic and unlikeable, but if you’re going to do it, and you’re not one of the group you’re deriding, then you’d better show them accurately and not rig the game in your own favor.

Which is why Ghost World so annoys me. Clowes’s teenaged girls don’t behave like teenaged girls. Here we have Enid telling Rebecca a story about meeting an old asshole, Ellis, and his kiddie raper friend. Ellis ‘humorously’ suggests that the kiddie-raper check her out, since she’s only 18.

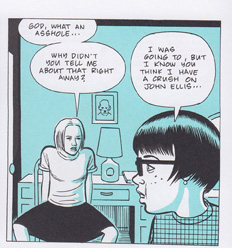

Rebecca’s response is shown below:

First of all, take a look at that body language. As someone who wears a skirt from time to time, let me tell you that girls rarely spread their legs like that while wearing a skirt. For one thing, it’s flat out uncomfortable. For another, we get nagged about spreading our legs or showing off our panties or what-have-you. Even in pants, spreading the legs is something that is usually done when one feels very comfortable and safe. It’s not something that a girl does when she’s just heard some bozo suggest a child-molester hit on her best friend.

This panel is not an accident. Look, I don’t like Ghost World, but Clowes has some drawing chops and he portrays body language effectively enough when he wants to. So what’s going on here?

A teenaged girl is not going to open her legs wide in a ‘take me big boy’ response, so why is she drawn this way? I can only assume that Clowes thinks a girl would have that response or because he wants to titillate the reader with Rebecca’s spread legs. Either option is unpleasant.

Then there’s the “lesbo” masturbation scene.

I’ve noticed that one of the ways Clowes mocks Enid is by having her mock people for something and then later having Enid do that mockable thing herself. Enid makes fun of a guy who she used to have something of a teen-romance with in high school. She says that he probably called her and jacked off while she talked. Mock mock mock ew say Enid and Rebecca. Then Enid visits an adult bookstore and picks up a fetish Batwoman hat and calls to tell Rebecca about the adventure. While on the phone with Rebecca, Enid takes off all her clothes and gropes herself while looking in the mirror (but doesn’t tell Rebecca). Mock mock mock.

It’s this weird circle jerk, but it doesn’t ring true. It comes off to me as something Clowes wants to think teenaged girls do, much in the same way that the high school boys I knew hoped the girls in the gym showers got up to steamy hanky panky. Never mind that in reality gym showers were places of horror, shame, body-fat hatred, silent prayers that you weren’t having your period (and if you were, that no one would find out–good luck with that) and tears. To the guys it was all a happy fantasy of hot girl on girl action.

Why is Clowes doing this? I say it’s to do two things at once: make fun of Enid for being a jerk and to fantasize about her and Rebecca in a sexual way.

Here’s a thought experiment. Take out the reference to Sassy and replace it with Lucky. Remove the punk green hair and replace it with a blonde ponytail. Switch the swearwords from fucking cunts to snooty bitches. Remove Bob Skeeter the astrologist and replace him with Ned the computer nerd. Pretty soon, if you took away the hipster faux-literary trappings and replaced them with mainstream teen story trappings, you’d have a boring and cliched tale of a couple of teenage girls who everyone loves to hate (and wants to date).

But maybe it’s not as OK as it used to be to hate girls just because they’re blond and pretty and not fucking you. So, instead of going that route, make the girls “real” by changing their outfits and the bit characters and the scenery. Then it’s not a cliched misogynistic screed, it becomes a “true” tale of how girls “really are”.

But it isn’t quite a tale of a guy who can’t get some, is it? No, because Clowes draws the main character wanting him. How much more proof could there be that this is a story about girls who are wanted/hated and the line between those two things?

There’s a fine literary tradition all about how women are shallow creatures and female friendships are suspicious and smothering. But if you’re a old dude perving on the sweet young things when you’re arguing it, it looks a teensy bit suspicious, is what I’m sayin’.

So let’s take a look at the so-called emotional growth and story progression of their relationship. What do they say and what do they do? Enid is thinking of going to college (to become someone new) and Rebecca decides to travel with her. What do they say about this? That it’s unhealthy.

Let’s take a look at that. It’s unhealthy for a friend to accompany a friend on a quest to become someone new.

Do you think that’s true? Because I sure as hell don’t. I’ve gone on several quests to make myself better, move someplace new (emotionally or physically), and been enriched and enlivened by the people who are by my side, traveling those paths with me. But Clowes, speaking through his characters, labels this as kind of creepy.

So what, exactly, does Clowes display as Enid’s growth? What is her progression?

If we take a look at the final pages, we see Enid in a new outfit. We’ve learned in this comic that changing outfits means changing who you are (at least for Enid), so let’s take a look at what’s she changed into. She’s well-groomed, with smooth hair done like Jackie Kennedy, and she’s wearing a neat, fifties housewife ensemble and carrying a hatbox shaped purse. Examine that for a moment.

Does this hark back to a desire on Enid’s part? Not as mentioned/drawn in the text, so we’re left interpreting the image in the way our society means it. Nothing says housewife quite the way a fifties outfit does. Is there anything (besides June Cleaver) that fifties suits and haircuts bring to mind, visually speaking?

Not that I know of.

What is this journey, anyway? It’s a journey of Enid’s current life, and it ends when Enid steps on a bus. What does that symbolize, within the context of story that Clowes has built? Erasure of self. Clowes likes to talk about it as creating someone new, but again and again he denies that Enid wants to be anyone specific. At the end, presumably after her emotional change (indicated by the dress, the diner voyeur scene and the bus) he gives her no identity except that of a very stereotypical fifties housewife.

That’s the “growth” that he lays out.

Ponder that for a moment and ask yourself whether it is, in any substantial way, a positive view of Enid. A positive view of girls, period. Whether it is anything besides the author saying, “Girls like Enid eventually cease to exist“. Not only does the author change them (into something trite), the girl herself wants to be anyone but herself. Herself is so awful she cannot be.

That’s a pretty hateful message when you get right down to it, and I cannot look at that as growth, as anything besides old fashioned misogyny and a desire to turn Enid into, bluntly, a wife. A person who exists not for herself, but who exists in relation to a man.*

But maybe I’m wrong. It’s been known to happen, and a single outfit is a small thing to base an entire textual interpretation on, right?

Right. Let’s look at the diner scene, which is the last line in the book, and the closure of Enid’s relationship with Rebecca. What does Enid say?

She says, “You’ve turned into a beautiful young woman.”

A beautiful young woman.

Look at those words. Consider the perspective of them.

Who is saying this? What is the relation of the woman in those words? To what aspect of the person are these words referring?

Enid (or Clowes through the character of Enid) considers this the mark of passage for Rebecca, the outside view, the praise. But what kind of praise is it?

It’s the praise of someone outside the woman, wanting her sexually, and has nothing at all to do with the woman’s internal desires, personal happiness, emotional growth, interests, community, relationships, or personhood. No, to say ‘She’s a beautiful young woman’ is to say she’s sexually desirable by an outsider.

And you know, as a bland statement of fact, it’s not so bad. But as a statement of a woman’s journey through a friendship and her creation of a new ideal self? That’s really fucking shallow, objectifying, and creepy.

This is not a tale of powerful female friendships post highschool. Nor is it a tale of emotional growth. It’s the same, tired story of how girls are shallow and their friendships are incestuous and unhealthy and most importantly how they need to become not-themselves. Gee, that’s deep. I’ve never heard teen girls and what they care about called shallow before! How original!

* Yes, I’m well aware that plenty of women are happily married. That’s not what I’m talking about, so let’s not go there. What I’m talking about is defining a woman only as her role in regards to men.

Note number two: I was an odd clothes wearing weirdo who read strange magazines, once upon a time, so I’m well familiar voices and inner worries of this group. Just so you know.

Enid isn’t dressed like a 50s housewife at the end – she’s dressed like a 50s co-ed. (Recommended viewing: Far From Heaven, Mad Men, Mona Lisa Smile, or you could, actually, you know, watch something, actually, from the 50s, maybe even, like, Dobie Gillis.) And it’s not a “hatbox-shaped purse”: it’s a train case.

What an exceedingly one-sided and negative piece. The analysis of that one panel is good and I’m sure it’s been established that Clowes may not be the best qualified to imagine what it’s like to be a teenage girl, but to reduce Ghost World to a misogynistic mockery of same seems to me grossly unjust.

As I wrote elsewhere, it’s been a while since I’ve read it and I shall look forward to doing so with this critique in mind, but I doubt I’ll find it any less moving a story of two *human beings* aging and drifting apart than I did the last time around.

She’s dressed exactly like all of my female housewife relatives did in the fifties, right down to the brooch on the tacky plaid shirt under a sweater, and I’ve seen a retro hat box bag like that. Maybe it’s a train case, and that’s fine.

In the real world, there wasn’t anything preventing a housewife from dressing like a co-ed or vice versa. But it was “the co-ed look”. It doesn’t signify the “stereotypical fifties housewife” to anybody who has ever paid much attention to the 1950s.

“Is there anything (besides June Cleaver) that fifties suits and haircuts bring to mind, visually speaking?”

You might want to rent “Playboy’s Penthouse”, which ran on television in 1959 and featured Hugh Hefner and bunnies with 50s haircuts. (I also highly recommend the DVD of the entire run of Playboy in the 1950s. There are some great “housewife” cartoons.)

For indie-er flair, you might want to look at Robert Frank’s photographs and film Pull My Daisy, Deitch’s cartoons for the Record Changer, Bland’s Cry of Jazz (often called the first hip-hop film), there are some great clips of Beat women in suits on youtube…

speaking as… well speaking only for myself and not for other adult males in general or anyone else in particular, i don’t see any titillation in the spread-legs shot. i don’t know how i feel about the composition of that panel as a whole, i like enid’s expression though…

anyway, back to the point, i think i would probably be more comfortable with it if the signifiers were, as you suggest, replaced with cliche “shallow girl” signifiers (lust after these hateful bimbos), but i would probably think about it less. the stuff i did find almost titillating (that’s not quite the right word maybe provocative is closer), for example the image of a moon-faced, blank, wide-eyed enid staring directly out of the page at the reader, are images that are actually pretty discomfiting.

emotionally what i take away from ghost world as a description of characters is these girls are almost complete jerks and know it but aren’t really happier for it. i can’t really point to anything in particular from this or clowes’ other work, but i never really felt he was harping on other peoples’ hypocracy, just kind of protraying most of the people in his comics as basically insecure, which ties into ghost world in other ways as well, noteably in the ‘detachment’ (elaborating off what i think caro said in a previous comment: the ambiguity of whether it’s introspective or more reactionary/defensive in nature)……..

i also just want to say that i don’t think clowes art is ugly at all. i like the way his people look, his line is pleasingly fluid and natural. that’s about all i can think to say for now.

In this particular case, I’d parse the outfit as exactly the opposite: largely because of the reference to her as Zelda, who does (according to the 1988 movie) marry Dobie and turn into a housewife, with a hostess apron and a girdle.

In contrast, Enid puts on her cardigan, fastens her brooch, grabs her train case and gets on that bus…that’s no housewife. That’s not June Cleaver. That’s Joyce Johnson.

Well, the textual implications are interesting, I think. One of the things that is left ambiguous is where she goes, but I would say that there’s as much as textual implication for her outfit to symbolize marriage because Enid is (at least in some ways) a shout out to Erika, who did meet and marry Clowes. (I don’t know whether she got on a bus to go find him, I’m just making it a suggestion.)

“(elaborating off what i think caro said in a previous comment: the ambiguity of whether it’s introspective or more reactionary/defensive in nature)……..”

Yup, that was me. :-) It’s not ambiguous to me, though, anymore; I’m pretty well settled on reactionary/defensive.

“I would say that there’s as much as textual implication for her outfit to symbolize marriage because Enid is (at least in some ways) a shout out to Erika, who did meet and marry Clowes.”

True enough. I really like that it’s ambiguous like that, though.

I was really amazed about that legs-spread, talking about the child molester panel. I thought some of the same things. Why the hell are her legs spread like that? Clowes can’t think that’s what a girl would do, especially in that situation. And surely he isn’t stupid enough to put in in there to be titillating. I don’t think he is. I can only assume it’s supposed to be ironic. I find that explanation less off-putting, but not hugely.

I think the outfit at the end is Enid’s take on grown-up hipster, which doesn’t thrill me, exactly, as short-hand for where she’s heading. Because it’s not much of a change, is it? Swapping one ironic costume for another.

I don’t think Ghost World would seem like it’s trying to be edgy, different, or hip to anyone outside of mainstream comics fandom. Music references, cafe settings, the word “fuck,” and characters who half-jokingly describe other characters as satanists don’t seem particularly “out there” to me, at least.

I don’t see the book as an attack on shallow high-school girls, either. As people have pointed out elsewhere during this roundtable discussion, Enid is largely an autobiographical character.

I disagree, Jack. Ghost World is wallowing in hip. If Ghost World referenced hipster-isms any more it would be – I don’t know, the American Apparel factory and Williamsburg and every big, ugly pair of glasses you’ve ever seen, all rolled into one.

I’m also not sure Enid is supposed to be autobiographical, or at least not exclusively so. (See Suat’s post re. Mrs. Clowes.) But even so, that doesn’t mean people aren’t going to react to the character as the character.

I don’t know, I’m not even totally sure what a hipster is.

Like I said in another post, I thought Clowes was trying for something of a modern Catcher in the Rye with girls. Both books deal with the theme of adolescents who find American adult culture empty and phony in contrast to the innocent childhood stuff (the dinosaur park, the Smile and a Ribbon record, the record Holden gets for Phoebe, the girl who lines up her kings in checkers, etc.) that they love. In Ghost World’s case, the author seems to attack both mainstream culture like sitcoms and political ads and “alternative” culture like the Answer Me-ish magazine by the John Ellis, with Enid remarking that the two cultures are the same thing. Lots of people despise Salinger’s writing because of its “good, sensitive people like me vs. the shallow phonies” attitude, and I can understand people reacting the same way to Ghost World. I just don’t see the hipsterism and misogyny that Vom Marlowe describes.

I found this whole piece pretty baffling, and a pretty extreme example of dissecting the perceived intentions of an author of a text rather than the text itself. That skirt panel to me is a pretty clear example of bad figure drawing, and the idea of it being titillating is pretty far-out. I would love to meet the person who thinks that’s a sexy panel. Additionally, I have met plenty of people like Enid, and find her to a fairly believable portrait of a person. I don’t think Enid, or Dan Clowes, would find her a particularly good representative of her gender, or her generation, as a whole. Does every female teenage lead have to represent her entire gender and age, or only ones written/drawn by men in their twenties?

Well, all I’m seein’ in the “legs spread” panel is the strongest possible visual. BIG ASS chunk of black, way down at the bottom, gives us vertical and horizontal symmetry (sans the though balloons) with Enid’s hair.

And, honestly, the rest of it… Our ideas of logical argument progression are so far removed I can’t imagine that arguing would do anything but make me tired, alcoholicy, and sad, sad, sad in my heart.

Who’s next?

How did you manage to decipher the chicken scratches on the bus terminal wall well enough to transcribe this and post it?

SERIOUSLY WACKO.

Uland, please try to avoid personal attacks as the roundtable fades into the sunset, huh? I have enough trouble fighting the spambots at this point without trying to scrub out a flame war.

I think, with Matthias, that VM’s take on the spread-legs panel has Clowes dead to rights. I don’t think pleading formal competence (with Mark) or incompetence (with Sean) is very convincing; whatever his formal talents or limitations, he chose to pose her in an improbable and sexualized manner. Maybe he did it because he thought it looked nice; maybe he did it because he can’t draw and figured this was the best compromise he could come up with. Either way, formal decisions don’t negate thematic ones, and I think VM’s objection stands (especially for an artist who everyone is constantly claiming introduces layers of meaning and ambiguity into his work.)

I guess I’m not as convinced by the argument that Clowes sees the girl’s relationship as “unhealthy.” That is, the girls say that the relationship is unhealthy, but I’m not sure Clowes endorses that view.

“Does every female teenage lead have to represent her entire gender and age, or only ones written/drawn by men in their twenties?”

Clowes was in his mid-thirties, just by the by. And I don’t think anyone’s suggesting they have to represent their entire age or gender. I think, however, that the book is often portrayed *by its advocates* as providing a particularly perspicacious understanding of teen girls. In addition, the fact that Enid and Rebecca are so much not there — that they lack specificity in a lot of ways — I think suggests that Clowes himself was presenting them as iconic (Mark used the word archetype somewhere on here, I think.)

I think VM is basically right in thinking that Clowes’ attitude towards Enid and Rebecca is suffused with disgust and desire, and reacting negatively to that seems pretty reasonable to me.

Nonsense. I think the legs spread a part thing was more about posing her as though she had just thrust herself forward from a more normal position- “What!? Why didn’t you tell me?!”- upon hearing what Enid had to say.

This half-assed Fruedian psycho/sexual stuff might be fun, but I think you guys are jerking yourselves off a bit here.

It’s starting to sound like my drunken uncle rhapsodize about human nature by talking about the “cave man days”; anything he wants to get after can fit into it.

You’re suggesting that using Freud to think about Clowes is illegitimate? Really? The guy loves David Lynch. He’s a part-time surrealist. I find it hard to imagine he hasn’t thought about Freud a good deal.

I’m kind of with Uland on that panel. I thought she’d been leaning the chair back and rocking it and had just dropped it to the floor.

Signs point to yes: Even the press for “On Sports” says “Freudian.” I was also told at dinner that there is an Eightball cover themed “The Psychopathology of Nostalgia.”

I don’t buy your Mary Sue arguement regarding Clowes’ insertion in the story. After all, doesn’t Enid see Clowes at a signing and is put off by his grotesque Don Knotts-esque appearance?

Erika Clowes teaches Freud at Berkeley, I guess.

No it’s not Freud, it’s random, half assed applications of Freud.

Ah, well; that’s a matter of opinion, of course.

No, you need more than an image of a girl seated without her legs crossed to put that stuff to work.

Come on, man. Everyone else has packed up and gone home. It’s dead.

Yeah yeah yeah, bla bla bla, people will still be reading and loving Clowes’ comics long after your boring blog and boring “critical” writing is long gone.

I’m really fucking sick of people who think that writing half-baked criticism is anything special, your no better than some blowhard on Yelp ranting and raving about his cold pizza.

Somebody write some god damn comics, please! with some stories in them, for the love of god.

I agree; it’s all so ephemeral, this blog writing. Random snarky comments on blogs, though…those are of permanent worth. Thanks so much for adding to Clowes’ reputation in this manner. I’m sure he’d thank you.

Well obviously you’re bringing me down with you. But seriously what do you expect posting a rant calling Clowes’ Art “purposefully ugly” ??

“Ghost World is wallowing in hip. If Ghost World referenced hipster-isms any more it would be – I don’t know, the American Apparel factory and Williamsburg and every big, ugly pair of glasses you’ve ever seen, all rolled into one.”

You obviously didn’t read Ghost World in its context, which was written from 1993-1997, long before American Apparel existed and Williamsburg was a crumbling Hasidic Jewish & Hispanic neighborhood.

If anything the relentless waves of hipster fashion – once a marginal lifestyle of vaguely punk-ish art school dropouts, now big business $$ – borrowed from people like Clowes, took the aesthetic of underground comics and music and everything else learned how to re-package it and sell it to teenagers.

Lumping Clowes in with that lot is pretty harsh, not that he’s a holy man, but I think his work comes from true desire to tell a good story, rather than just making bucks off the latest trend.

Believe me, there were PLENTY of girls just like Enid and Rebecca, especially in 1993, and they all read Eightball.

I think the idea that punk rock ever existed in a pre-appropriated Edenic state is…well, let’s just say I don’t agree with you, maybe, and leave it at that.

I think the art is purposefully ugly. He’s intending to show the unpleasant shallowness of suburban existence, and so he chose a deliberately hideous color scheme (among other choices.) I think even many people who like the book would find that analysis unexceptional.

You all must have read a completely different comic than I did. If you came away from this thinking that Clowes is mocking Enid and Rebecca as “shallow teen girls”, then I think you missed the point, not to mention most of the story.

It’s clear that some of the negative commentary is driven by personal issues. Noah has a beef with the fact that Ghostworld is overrated and feels very driven to bring it down, ala his take on so, so, so, many artists. The kitty is angry that she is a hipster who is compared to Enid– she is worries that she appears inauthentic is others eyes– a real irony — this should lead her to identify with Enid, who shares those worries. Neither Noah or Kitty see the book, only their own issues projected onto it. Even some of the positive roundtable commentary has factual errors. This roundtable has been pretty bad when compared to the threads at comics comics. Groth lamented the lame online criticism and then is in part responsible for this . . .

Right, and it’s clear that your negative commentary is driven by the fact that your parents looked like Gary Groth and the Comics Comics website.

People have different opinions than you. It doesn’t have to be personal. Get over it.

There are some smart things here: Reece, for example, and a few folks in the comments.

Kitty admitted as much in her post — I am just repeating her. Don’t you see the irony of saying don’t make it personal and then taking about my dad and mom, who are handsome like Groth.

You want the ability to be personal and negative in your explanation of Clowes and his motives, yet you insist that you be free from such similar analysis. He is a writer and you are a writer–both of you can be criticised.

And so can you! i didn’t delete your comment; I just said you sounded like an idiot. And I stand by that.

Can we both then acknowledge our hypocrisy, our double-standards? I do.

I think people get over-excited by hypocrisy, really. Everybody loves saying “you’re another”…but I don’t think that it’s necessarily all that big a deal most of the time.

I don’t think you were out of line or hypocritical. I just think you were wrong. There’s nothing especially immoral or hypocritical about disliking a blog post or, for that matter, a comic book.

Fair enough.

I re-read a few stories from Caricature the other night.

Many times more inspirational and satisfying than reading this quasi-intellectual dreck.

Reading Clowes makes me want to draw comics. Reading this blog makes me want to write angry blog comments.

That’s fine. I would suggest you stop reading this blog, then. No one’s forcing you.

Yawn. If a female character ever acts less than admirably, the author is misogynistic. (of course if the female character is portrayed as nothing but admirable, the author is accused of putting women on a pedestal which is also misogynistic). Art appreciation for many has pretty much become a game of “spot the sexism” these days.