I was interested in setting up a Ghost World roundtable because it’s a book I’ve had mixed feelings about. Well, that’s not exactly right. I’ve always pretty much hated it, actually. But I’ve had some trouble figuring out why I hated it. Which is unusual for me; as a rule my bile flows fairly glibly. I mean, yes, there are some loathsome aesthetic choices — the heinous blue-green spot color being the most obvious. Beyond that, though, I’ve never been able to quite wrap my head around what about the book so thoroughly irritates me.

In this regard,Kinukitty’s post Charles’ essay and Richard’s post have been helpful. Though kinukitty disliked the book, Charles liked it, and Richard had mixed feelings, their reactions actually have a good bit of overlap. For all of them, the book and its characters are defined in large part by absence. Kinukitty says of the characters “I don’t recognize them as high school girls, but that is probably secondary to the fact that I don’t even recognize them as human. They are not so much characters as collections of anecdotes that are intended to be cool and ironic… I think Ghost World is unpleasant in a way that winds up being pointless because there’s no there there.” Richard notes that Enid eventually heads towards adulthood, but that she displays “a maturity without content, which invites that the reader fill in the blanks with their own experiences.” Charles comes at a somehwat similar point from a different angle, arguing that for Enid, “Mass culture has even detached us from our detachment.” In other words, the book’s pointlessnes and Enid’s lack of a center is, for Charles, thematized; it’s an example of our modern, or postmodern dilemma. Ghost World is a world where there is no meaning; where you can’t even recognize others as human, where we’re all just collections of anecdotes, alienated from our own stories.

I think Charles has also made a very astute point — though not quite the one he intends — in linking Ghost World to the work of John Barth. Clowes is often discussed in terms of filmmakers like David Lynch, I think, but he’s always struck me as being more allied with contemporary fiction — not least because of his flatness. Lynch, for all his auteurishness, has a lot of pulp at his heart; he likes the flamboyance of horror or heist films or psychological thrillers. He may make films about emptiness and the break-up of identity, but the films themselves are filled with pyrotechnics and a weird kind of life. They’re not a blue-green blank.

Literary fiction, on the other hand, often is. “Middle-aged academic types” as Charles quips, abound; it’s a genre of mid-life crisis. And indeed, Barth’s The End of the Road, from Charles description, sounds very much like…well, here’s what Charles says about it:

Horner is a middle-aged academic type who’s managed to think himself into a hole, not seeing any potential action as better grounded than another – sort of an infinite regress of self. Thus, he’s sitting in a bus station in a state of existential paralysis, not able to even come up with a good reason to get on a bus and leave his former (non-) life behind.

That’s tricked out with intellectual filigree, but basically it’s a mid-life crisis, right? Garden variety despair at getting halfway through your existence and realizing you haven’t done all that stuff you wanted to do when you were a kid; you’re not on top of the world, you’re just some bourgeois scmuck like every other bourgeois schmuck, so you sit there, unable to go forward, unable to go back. Okay, now, hurry up and write a novel explaining that it’s not just you who’s lame — it’s a universal, existential condition!

So hold that thought, and let’s consider Enid for a moment. Enid is in almost every respect an extremely odd teenaged girl (as kinukitty points out). She seems acidly alienated from pop culture and music. She’s uninterested in discussing her crushes, or, indeed, discussing enthusiasms of any sort. She has an extremely guy-like instrumental approach to sex, based largely on scoring points and talking to her friends afterwards. And she turns for solace, not to booze, or drugs, or sex, or crushes, or pop songs, or movies, but rather to totems of her childhood; random theme parks she visited as a kid, random toys; half-remembered kids songs. Enid is desperately nostalgic for her youth — which is more than a little weird when you’re only, what? 17?

Oh, yeah, and she has a fascination with creepy borderline psychos. Who are older. And male.

Not that it’s impossible that a teenaged girl would act this way, of course — people are different after all — and certainly lots of young girls are fascinated with creepy older guys. But…well, for example, Ariel Schrag is more or less in Enid’s bourgeois demographic. And her adolescence, based on her autobiographical comics, was certainly filled with anguish of various sorts — her parents divorced, she went through a painful process of questioning her sexual identity and she had a number of extremely traumatic relationships.

But…Ariel didn’t live in a ghost world. She had lots of serious problems, but they were problems that you have when you’re young — which is to say they were problems caused by not being able to understand, or process, or sort out a cascade of emotions and desires. Ariel’s difficulty wasn’t that her world was fading out, but that it was too sharply coming into focus, and there was too much of it. It’s the intensity of her emotions — her crushes, her attachments to friends, and, indeed, her attachment to her art — that makes her life a misery. Sometimes. And, then, at other times, that same intensity becomes a source of strength and beauty and excitement.

Now, that second bit doesn’t have to happen necessarily, and doesn’t for a lot of adolescents. Youth can be great (which is why people romanticize it at times) but it can also really suck, and the sucking can easily outweigh the good stuff, and does for lots of people. But the point I think is, when adolescence is miserable (as it absolutely can be) it tends to be miserable the way adolescence is miserable, and not miserable like middle-age.

Ariel Schrag wrote her autobiography when she was an adolescent, and that’s how it reads. Dan Clowes wrote Ghost World in his mid-thirties…and that is so, so, so how it reads. Enid, it seems to me, makes most sense not as an accurate portrayal of a teen girl, but rather as an accurate portrayal of a thirtysomething man enjoying himself by pretending to be a teen girl.

And, indeed, as that, Ghost World is undeniably kind of brilliant. Most of the intellectual content of the book is little more than the clichéd crankery of the past it hipster, bitter that he’s no longer up on all the latest bands, pining for his youth while simultaneously loathing and desiring the young. Put those sentiments in the brain of a college professor and you’ve got just another novel by John Updike…or, perhaps, John Barth. But hand the sentiments off to young girls — that’s kind of genius. Have the girls sneer at Sonic Youth for you; have the girls moon after the detritus of their youth; have them say of each other, with just a touch of condescension, “You’ve grown into a very beautiful young woman.”

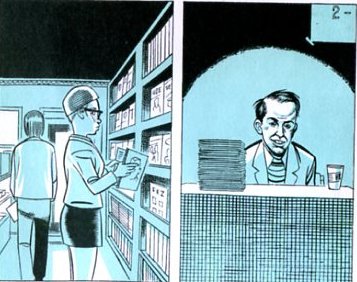

Perhaps the most emblematic moment in the book, in this respect, is when Enid meets (a thinly disguised) Clowes himself. This is, to the best of my recollection, the only time in the narrative that Enid expresses an unironic connection to, or enthusiasm for, any piece of contemporary pop culture. Yet, when she sees the “real” Clowes, she is disappointed because nobody else has come to see him and he is “like this old perv.”

Clearly this is supposed to read as self-effacement on Clowes’ part. But I wonder. Enid’s initial fascination (which is in part sexual) is certainly a fairly familiar creator fantasy (“she loves me for my art!”) But even more than the enthusiasm, it seems to me that the disappointment is a kind of sublimated self-aggrandizement. After all, Enid’s let-down is only really possible because her interest in Clowes, like all of her interests, is without content. We never learn what she likes about faux-Clowes, or what it is in his books that inspires her. Who is Enid? She’s no one, a ghost without purchase on her world or her culture. And why is she no one? Whose ghost is she?

Surely it’s significant that, as this sequence suggests, while Clowes can imagine Enid, Enid can’t imagine Clowes. Indeed, the page reminds us subtly that it is Clowes calling Enid into being; we see her from his perspective first, and only then can she see him. Enid’s self isn’t there not because that’s the way it is for all of us in this sad state of late postmodernity, but simply because her self isn’t hers. She’s somebody else’s mid-life crisis, there to buttress another’s existential vacuum with the weight of her own nonentity.

______________

also, enid coleslaw = daniel clowes, an anagram.

So it is!

“the heinous blue-green spot color being the most obvious.”

Seriously? It looks sickly and muted. It fit the tone of the book perfectly.

Sidenote: Maybe I’ve been too hard on Ariel Schrag. Is it fair to, critically, dismiss a work because I think teenagers are annoying in large doses?

I like Ghost World a lot better, (and have since I was 18-19) probably because I prefer adolescence-retrospected through adult sensibilities. I certainly EMPATHIZED more with Schrag’s narrator, but I didn’t have much of a reaction beyond that. “Yep. Been there.” “Been there too.” “Did that.” “Well, didn’t get laid as much (read: At all) but it rings emotionally true.”

“Fuck, I could’ve written this.”

Oh wait. I was gonna write about the Dan Clowes bit. A little bit of self-put-downishness, sure. But the scene was really about Enid, and it’s a universal-growing-up thing. Your heroes are NOT what you imagine them to be. Girl learns a lesson, moves towards adulthood.

Yes, the book is supposed to be ugly, and the blue-green is ugly. It’s not thematically wrong. I think it’s still aesthetically wrong, though; or, at least, I have little interest in looking at a work that’s blandly ugly in this way, whether or not the artist intended it to be blandly ugly.

You’re heroes aren’t who you imagine them to be, maybe…but who did she imagine him to be? We get this one sexy-cool image…but why did she think that about him? What did his work mean to her? We don’t know, because Clowes doesn’t tell us, because he’s only interested in what Enid isn’t, not in what she is or might be. If she actually had a personality, or was into stuff that she really would be into, or even had a reason for liking him, she wouldn’t be the perfect empty vessel for him to sneer at and fill.

I think Ariel Schrag’s work is infinitely better in just about every way than Ghost World. Her story-telling skills are way, way superior to Clowes’ — you don’t ever see her resorting to the kind of cliched television special pop-psychology that Clowes retails to try to demonstrate that he, like, understands the girls (“you don’t hate yourself” — yeah, thanks Dan. Brilliant insight. Go to the head of the class.) Even in her first book, when she was in tenth grade, Schrag was better than that, and by the time she gets to Potential she’s flat out brilliant. And then Likewise is even better. I’ve got a review of some of her work here

“I think it’s still aesthetically wrong, though”

And crux-of-disagreement time. I think it’s cool lookin’ even pretty when it’s doing cityscapes.

Maybe. From the couple pieces I’ve seen that weren’t flat-out-diary.

“You’re heroes aren’t who you imagine them to be, maybe…but who did she imagine him to be?”

Who cares? “Your heroes.” Ghost World is doin’ archetypes, not characters.

“I think Ariel Schrag’s work is infinitely better in just about every way than Ghost World. Her story-telling skills are way, way superior to Clowes.”

I think Clowes is a better PANEL artist – The drawing of Rebecca on the cover of the GW trade perfectly captures the thing-ness of the thing –

But AS’ is a much better cartoonist sure.

I REALLY like every piece of short fiction I’ve read from her – The “Growing Up Anthology” thing, the couple pieces in Juicy Mother.

Pages and pages and pages and pages and pages (time infinity) of her high school experience – which was more or less the same as my high school experience – spelled out in minute-bordering on microscopic detail – I liked less. Although, again, in my brain: High School Kids = Marginally interesting. I don’t really disagree with anything you wrote in your review except for the degree of boring-ness. Contrarily, adults-looking-back on their high school experience can be interesting, because adults are more prone to say interesting things. (Little kids are kind of interesting too, because they’re batshit insane. I appreciate that.)

And obviously I disagree with “cliched television pop psychology” (Specifically: I could argue *counts* five different possible meanings for the “you don’t hate yourself” line, mostly depending on how much distance (ironic distance, or passage-of-time distance, or observational-distance) you ascribe between the guy-who’s-writing-the-thing and the material.

I think the round table is going to get a lot of different interpretations of how the book works because it’s subtle enough that there isn’t one easy reading. You’re entitled to your own (awful, awful, awful) Ghost World, of course.

Noah: I think Dan Clowes has been at pains to explain that the girls in “Ghost World” are really an extension of himself. I liked your expansion on this theme though. It may be that some reviewers have mistakenly advised readers to view “Ghost World” as a reflection of teen angst or reality but I really haven’t read enough “Ghost World” reviews of late to know this for certain. It may also be a side effect of the movie adaptation.

In fact, you seem to have pierced this veil quite easily in your article where you write, “Enid, it seems to me, makes most sense not as an accurate portrayal of a teen girl, but rather as an accurate portrayal of a thirtysomething man enjoying himself by pretending to be a teen girl. And, indeed, as that, Ghost World is undeniably kind of brilliant. Most of the intellectual content of the book is little more than the clichéd crankery of the past it hipster, bitter that he’s no longer up on all the latest bands, pining for his youth while simultaneously loathing and desiring the young.”

Clowes’ work almost never charts the straight reality characterized by the comics of Ariel Schrag hence the preternaturally sophisticated and nostalgic girl with “masculine” concerns and a mid-life crisis in her teens. People who like “Ghost World” are probably attracted to this tension. Afterall, as you indicate yourself, not everyone conforms to the peak of the bell curve. In fact, Clowes’ work might be the antithesis of the tradition from which Schrag comes from (Crumb->Chester Brown->etc). We should do a roundtable on Schrag, maybe on “Potential”.

Have you read Likewise, Mark? I think you’d be hard pressed to argue that that’s just formless anecdotes, or that it’s an uninteresting teen perspective (I don’t think that’s the case for any of her work, but Likewise is extremely ambitious from any perspective.)

I’d love to do a Schrag roundtable; kinukitty’s a fan too, I know, and I’m sure VM would like her work. Maybe even Richard might like it?

Clowes is obviously not necessarily about authenticity or realness. I’m sure he’d like to see himself as writing about archetypes. But, you know, his archetypal female adolescent behaves like a middle-aged man. To me it seems, as I said, like the book tries to justify and naturalize the particularly repulsive tropes of literary fiction by pretending their universal — not just the concerns of vapid middle aged men, but of young high school girls too! Add in the place that young girls generally occupy in the mid-life crisis narrative — it just comes off as really unpleasant wish-fulfillment to me, a way to turn the desired other into your own appendage. It’s sadistic, basically, though without the hyperbolic violence or brutality that can make sadism aesthetically enjoyable. Bland sadism. I don’t want to read that crap.

Noah: I think Clowes agrees with you in part but couldn’t help himself. Hence the reference to himself as a perv. I don’t think he sees himself as writing about archetypes, at least not in “Ghost World” which is really heavily filtered, fictionalized autobiography. I do believe it was written at a time when autobiography was king in alternative comics which also explains its attraction to comic readers at the time – it was something different.

Also, going back to the original article, the Lynch comparisons (which were mostly unfavorable or lukewarm I think) surfaced mainly because of “Like A Velvet Glove Cast In Iron”. “Ghost World” attracted favorable responses at the time because it was seen as a departure from this old shtick; one less grounded in fantasy and more with cultural commentary.

One note: I recall Matt Silvie(?) making a comparison several times of Clowes to Nabokov, which always seemed spot-on. Much more so than the Lynch comparison, as I’ve never read Velvet Glove.

I see the Nabokov comparison, I guess…but I think Nabokov is much better at confronting and dealing with the moral issues raised. Lolita and Ada (which are the books of his I’ve read that seem to fit here) take very strong moral stances, and both (I think; haven’t read them in a while) allow their female characters moments of insight into their male adversaries/creators which go beyond a sort of one off and unmotivated (and therefore in itself kind of denigrating) “ew.”

Pygmalion’s maybe a good touchstone too. The whole point of Shaw’s play is that, whatever’s is made of Eliza, she can and does speak for herself. Henry’s viewpoint is that of the playwright, but he doesn’t get to win the arguments by a long shot. In other words the point of Pygmalion is that Shaw/Henry can create Eliza, but she still has a there there; he can’t own her, or be her. The point of Ghost World is that Enid doesn’t have a there there…and thus in some sense I think that Clowes does own her, and can be her. Again, it seems really sadistic to me.

There’s a bit of Lynch in Ghost World — the Satanists, the girl with the growth on her face, touches like that.

Ah, your Pygmalion comparison’s the most illuminating of all.

Have you read Clowes’ “Caricature?” It’s in the same territory, only more intense.

Yeah, I hated Caricature too.

At least I’m consistent!

In this vein (Pygmalion), John Fowles’ Mantissa is pretty good–and of course French Lieutenant’s Woman is actually great. Man creates woman to represent himself (and get off)–but woman still thinks for herself, calls man on it, etc.

I was going to post a response to Richard pointing out how Clowes’ writing of teen girls as middle-aged fanboy geek is problematic. Glad I didn’t. What would Noah have added? (Just kidding).

I pretty consistenly don’t get the attraction of Clowes myself. Only read Ghost World and a couple of shorts, but I’m missing something. Seems like Chris Ware without the humor or the formal pyrotechnics–which is basically makes Ware fun to read.

I see the Nabokov link…but Clowes isn’t really in Nabokov’s league is he? “No”….that’s the answer I’m looking for.

Three cheers: excellent post. I don’t sense Humbert or sadism, though, lurking in the shadows, because of the order of precedence: the erotism, such as it is, isn’t turning “the desired other into your own appendage” but rather turning his “own appendage into the desired other” — which is at best onanistic and, at worst, even more narcissistic than the most banal autobiography.

Be fair to Barth! There’s plenty of truly flat contemporary fiction and The End of the Road isn’t the best example, but he does have layers: they’re just exploring the nature and structure of fiction rather than plumbing the emotional depths of his characters. If spot color is what passes for structural conceit in GW, then the equation is hardly just…

I’ve liked some Barth; The Sot Weed Factor is pretty great.

I see what you’re saying about narcissism vs. sadism. But I think there really is an effort in Ghost World to get inside the heads of teen girls; to play with them and see what makes them tick (or how they can be made to tick, I guess.) I think there’s absolutely an eroticism of discovery; of putting the other on the operating table, opening her up, and inserting yourself.

I guess the point is, in film theory especially, sadism and narcissism aren’t especially far removed from one another.

Eric, I absolutely don’t see Clowes in Nabokov’s league…or even David Lynch’s, for that matter. But obviously there are those who would disagree….

Clowes met his wife, Erika, at one of his signings. She ( I think) was in her late-teens/early twenties, while Clowes was in his early thirties. He either left his wife for her, or they’d divorced shortly before.

I don’t think Ghost World was ever meant to be some kind of naturalistic, ultra-*real* story; Clowes is winking and nudging throughout the whole book.

Well, barf. That information makes me like the scene even less, if possible.

I like Ghost World, but that was a pretty good post. Your take on the book is like a lot of stuff I’ve read by people who despise The Catcher in the Rye–they’re pissed because Holden is really Salinger and not a 16-year-old kid. Actually, I think Clowes may have consciously referenced The Catcher in the Rye by having Enid wears what looks like a hunting cap.

Clowes is a huge Nabokov fan, and the Vivian Darkbloom = Vladimir Nabokov thing is probably where he got Dan Clowes = Enid Coleslaw. Also, the credits at the end of David Boring seem inspired by the index at the end of Pale Fire and the class list in Lolita.

Hey Jack! Nice to see you over here.

I’ve only skimmed David Boring, and that was a while ago. I liked that even less than Ghost World, I think….

Noah: I agree — don’t take what I said as narcissism “vs” sadism, please. I just think that precisely because they are so connected, it matters that these teen girls on the operating table are, essentially, fantasy formations of the man with the knife.

We mostly know Lolita through Humbert’s fantasy of her (the narrative voice is Humbert’s own immensely narcissistic first person) but we glimpse a Lolita there that isn’t Humbert’s Lolita. There is no such doubling of Enid; the authorial voice is as singular in GW as the narrator’s voice is in Lolita.

For all the characters’ ironic detachment, GW itself lacks critical distance. Clowes isn’t detached enough to transform observation and representation into a meaningful literary conceit. The tension between the Lolitas in and out of Humbert’s head is the mechanism that lets Nabokov make the immensely powerful and very adult point that Humbert’s failing was not his sexual proclivity but his inability to see it as violence rather than love. The meaning is in the space where Humbert’s narcissism turns into sadism, in the (failed) intersubjective interaction between the “real Lolita” and Humbert’s extraordinarily selfish perception of her, and in the insight we gain from witnessing that failure.

But there’s no moment when I feel like Clowes has even thought of your point about sadism and no moment when he allows the complexity of the adult man’s relationship to the teen girl character to play out, let alone makes something literary out of it by paying attention to it as “intersubjectivity” rather than “interaction.” That’s terribly disappointing, because it either requires us to ignore your point and accept the book as merely this “sweet sentimental story about teen disaffection in postmodernity”, or make apologies for why Clowes ignores it (Charles’ interesting point about capitalist alienation is going in that direction, but it’s a little bit of him being smarter than Clowes.) Neither one is particularly satisfying.

This is getting off topic, but Caro, can you expand on what you mean about Humbert not understanding Lolita? As a narrator, he seems to have some appreciation for her being more than his sex fantasy. At one point he describes a comment she made about dying and says that parts of her mind were hidden from him because their relationship was totally evil. And by the end of the book he’s totally accepted that he’s a rapist who stole her childhood.

Fine post Noah — I think you articulate a lot of Clowes’ Flaubert-turn in the book, and I agree it’s brilliant, but much more unreservedly than you do.

It’s been quite a while since I read GW but I still remember it as an emotionally very powerful book, which is why I just cannot fathom statements like this:

“Ghost World is a world where there is no meaning; where you can’t even recognize others as human, where we’re all just collections of anecdotes, alienated from our own stories.”

The whole point of Enid’s development, as I remember it, is precisely an emotional maturation, and I see no condecension whatsoever in the book’s final line. Rather, it’s painfully honest.

This is where Clowes is such a master — the sudden revelations of the emotional undercurrent to his seeming cynicism and postmodern detachment. Another moment is at the diner, when the poor slob they’ve conned into a non-existent date figures them out; a painfully raw confrontation with real emotional reality.

Hey Matthias. I found both the final line and the diner scene deeply glib and false. Since Enid doesn’t seem at all like a teen girl to me, the emotional “revelations” all come across as Clowes either sneering at others to whom he has attributed his own sins, or else as patting himself on the back.

But, obviously, mileage differs….

Sure, Jack: I do accept the justified call out for oversimplifying because there’s a tremendous amount of doubling in Lolita, certainly including the Humbert who “loves” Lolita and the Humbert who admits it’s wrong (although I’m not sure admitting is understanding). I really wanted to point to one single instance of that doubling and its impact in that book to underscore how little similar doubling there is in Ghost World and how the absence of it limits what Clowes can accomplish.

So indeed, Humbert acknowledges that Lolita is more than what he fantasizes her to be, but I think his awareness that this “passion” is very corrupt is held very separate from his memory of it. (There’s that whole business of referring to her by other names when she’s “not Lolita”.) Throughout, the relationship remains immensely romantic to him. Even when he is explicitly acknowledging the immmorality, he always uses this really lush rhetoric to talk about her. I can’t find an instance where he talks about her that it isn’t filtered through his image of her as his “lover”: “I knew I had fallen in love with Lolita forever, but I also knew she would not be forever Lolita.” At the end, he claims to be “protecting” her, still addresses her directly; in the last phrase of the novel, he still calls her “my Lolita”.

That’s why the fantasy seems so singular to me I think, despite the varied protestations throughout. And if that singular fantasy was all there was to the book, it would be much less powerful. But instead we have all these layers of other things.

A better comparison with Ghost World might be Hawkes’ Blood Oranges, despite the lack of the teen/adult dynamic, because that’s a situation where the author allows the narrator’s (suspicious, unreliable) voice to dominate throughout, without much overt doubling at all. I’m not sure I buy that the voice in GW is meant to be suspicious and unreliable like that, but even if we grant that, I certainly don’t see Clowes turning those moments of unreliability to meaningful effect – maybe some of the folks on the list who are more dexterous with the graphic idiom than I am can point me to places in GW where the consistency of the characterization breaks against something in interesting ways that form the foundation of more complex meaning, but when I look for the kinds of things that contemporary fiction does (c.f. Noah’s comparison) I don’t see them. I don’t see Lynch either, though: Ghost World just reads like a pretty straightforward young adult novel to me.

Thanks, Caro. Yeah, I guess (“Why do these people guess so much and shave so little?”) I agree with that. You can also see his twin attitudes toward her in the Quilty execution scene, when he comes across as the avenger of “my child”‘s rape and a jealous lover at the same time. He has the great moral apotheosis about her voice missing from the choir, and he still wants to be her when she’s 16 and pregnant, but he remains an enthusiastic pedophile all the same… It’s hard to pin that character down.

Sorry, “be with her.”

Caro – “But there’s no moment when I feel like Clowes has even thought of your point about sadism and no moment when he allows the complexity of the adult man’s relationship to the teen girl character to play out, let alone makes something literary out of it by paying attention to it as “intersubjectivity” rather than “interaction.”

That’s because the adult man appears in one panel in Ghost World, he said, trying really hard not to be sarcastic. I believe that it is useful to differentiate between stuff that’s actually part of the book and interpretations based on the timeless critical process called “making shit up.”

NOAH

“Have you read Likewise, Mark? I think you’d be hard pressed to argue that that’s just formless anecdotes, or that it’s an uninteresting teen perspective (I don’t think that’s the case for any of her work, but Likewise is extremely ambitious from any perspective.)”

I read four of them. I don’t remember titles. Mostly just images, a FEW plot points, and the time that I was on page 13,678 out of 38,466 and said “I’m pretty far along in this boring book. I am a hero.”

And then she STOPPED USING GODDAMN FUCKING PAGE NUMBERS for like a hundred pages, and the book picked up AFTER A HUNDRED PAGES on page 13,679, so the book was actually WAY LONGER than it said it was. Which, granted, was formalistically kind of clever.

But when I decide the author is actively out to get me, then we can’t be friends.

I think Clowes’ relationship with Enid is pretty important throughout. The anagram suggests Clowes certainly felt there was some connection there. And there are a number of older men who can be seen as stand ins for Clowes; that weird guy at the end who reads her fortune, for example, has a pretty structurally important place. I don’t think the movie was necessarily making shit up when it decided that the story was about intergenerational romance.

I guess if Likewise didn’t do it for you, it didn’t do it for you. It is pretty modernist and/or not user friendly in some ways, certainly. I found it incredibly moving and thoughtful and rewarding…but I can see where someone might be put off by any number of things about it, I guess.

It’s probably my favorite American comic of the decade though. Or in the top 5, certainly.

“I think Clowes’ relationship with Enid is pretty important throughout. The anagram suggests Clowes certainly felt there was some connection there.”

I read that as a take-off of the old author-interview chestnut “Every character is an aspect of myself.” It’s so common as to be..

Well, IF they’re telling the truth it’s so common a response as to be meaningless.

(Although I suspect that it’s more a deep and author-y sounding comment than a true one.)

Likewise – Yeah, I guess I can see that there are a lot of things that someone who isn’t me would like about the writing, and if it was Ghost World length I might’ve liked it. I just don’t get why anyone would need to relate in real time – not even examine – their high school experience over near a thousand pages.

Well, as I said, I think it’s unusually true in this case.

I don’t think you’re going to really be able to sustain that argument that Likewise doesn’t examine her high school experience. The details and the mode of transmission are very carefully chosen. It’s structurally quite complicated; she uses stream of consciousness in some places and then changes narrative styles at others to make particular emotional thematic points. The changes in art style throughout are also very controlled and thought through. I’m not saying you have to like it, but I don’t think the criticism you’re offering here sticks.

Mark — give me a stimulating reading that isn’t about this intergenerational dynamic and I’m happy to talk about it instead.

But it is the issue raised by Noah’s post, which I really like because it took a book I’ve always thought was rather simple and dull (“emotional”, sure — but I find mere representations of emotional states dull) and suddenly raised the Spectre of Perversity. I appreciate the possibility that Clowes is somehow engaging in conversation with books I don’t find dull in the least and that perhaps there’s something more ambitious going on that I’d given him credit for previously. You can call that “making shit up” if you like; my feelings won’t get hurt.

(Just to be clear for Mark’s sake: I appreciate the possibility that Clowes is having this conversation. I remain at this point, unconvinced. But less convinced of the opposite than before. Thanks, Noah!)

“Likewise doesn’t examine her high school experience. The details and the mode of transmission are very carefully chosen.”

Eh? I don’t follow.

“It’s structurally quite complicated; she uses stream of consciousness in some places and then changes narrative styles at others to make particular emotional thematic points. The changes in art style throughout are also very controlled and thought through.”

OK, this I see and agree with.

But it doesn’t equate with “examining” in my eyes. There’s plenty of both formal play and using formal comic-cy tricks to increase the effectiveness of the story, but it’s still only from the POV of a high school kid who’s violently emotionally invested in the story that’s happening (even when the story is about being emotionally removed because she’s ALREADY writing this as a comic in here head.*) It’s the difference between writing a diary and writing a diary WELL. (Although, in this case, Mad Drawing Skillz and formal experimentation take the place of… um… good writing.)

* That bit about o

I meant “does examine”; that’s probably the confusion.

She’s certainly emotionally invested…but there’s a story arc, and her emotional investment is thematized and thought through. The book’s a process text; it’s about writing itself, and she lays that out very carefully. I’d also argue that individual writing bits are pretty amazingly done; the stream of consciousness is often hysterical; the characters and their interactions are subtle and complex. One of the things I love about her writing, in fact, is how, despite her emotional investment, she manages to present herself very coldly, and to give other characters voice and agency.

I don’t know…I mean, part of what you seem to be saying is that you don’t care what high school kids have to say. You also seem to not like, or think there’s something wrong with, diary writing. I fairly violently disagree with both of those stances, for lots of historical, cultural, and political reasons which I maybe won’t go into here. But, yeah, if you don’t want to read the writing of high school kids and you don’t want to read diaries, for whatever reason, Schrag isn’t going to be all that interesting to you.

Noah: “You also seem to not like, or think there’s something wrong with, diary writing.”

I’m not Mark but he doesn’t appear to be saying that at all. From his comments, it would appear that he thinks that Schrag’s “diary” is poorly written. He also appears to be suggesting that he finds the thoughts of other writers (possibly older and more experienced) more relevant and insightful.

This is why we need that Ariel Schrag roundtable. Her work is relatively new and undiscussed and the kind of work which the current generation of alternative comic readers supports. Clowes and Ghost World are for old timers like myself.

No; I’m pretty sure Mark’s saying that Schrag may be writing a diary well (substituting formal experimentation and drawing skills for good writing) but she’s still only writing a diary. Perhaps he’ll clear it up for us though.

You know I’m almost 40, right Suat?

I wish I felt that the current generation had more love for Schrag’s work. I think she tends to be criminally ignored by everybody, actually (though Shaenon’s a fan.)

We’ll definitely do a schrag roundtable. Not sure if it’ll be the next one, but before too long.

“Well, barf. That information makes me like the scene even less, if possible.”

I think the look on “Clowes'” face in that scene is pretty hilarious. I really don’t get what’s so gross about the whole thing. I just don’t see it. He’s winking at the audience, acknowledging a certain creepiness, while maybe writing a secret note to his wife.

I don’t have anything against diary writing, but you’re kind of right on High School Kids – If they’re going to write about the experience of being high school kids I want CONTENT I haven’t heard before or personally experienced – I want new story, not just the story I’ve lived told in a new way.

“give me a stimulating reading that isn’t about this intergenerational dynamic and I’m happy to talk about it instead. ”

I guess I can’t say the intergenerational reading is WRONG, since Ghost World seems really deliberately ambiguous – I’m honestly not sure

what Clowes feels about the main characters. He’s trying really hard to make them both (A) unlikeable, (not particularly pleasant people) and (B) likeable (clever, witty, having interesting hobbies)

But, c’mon, if you’re going to chase this line of argument guys you have to account for Josh, who’s by far the most important male character in the piece.

Although he definitely seems to have some affection for them as of the Deluxe Hardcover Reprint with Two! Pages! of New Content that was released this year.

But the basic subtext-type-stuff is pretty easy, right? It’s all finding the boundaries of your little world and asking “is this all there is” and the response to that – Trying to make yourself into a fairly unpleasant person, as artificial a construct as the fabulous fifties diner. I can see how this might be an important element in the emotional life of a middle aged cartoonist, but it would work better with a teenage-girl-archetype, because the experience would be more real. You don’t KNOW the world goes on beyond your immediate experiences.

So I got home and read Ghost World through again, looking specifically for three things: disaffection –> emotional maturation/emotional resonance, the gaze of the adult male, and the unreliable Nabokovian narrator. (Google sends me to Comics Comics quoting Clowes referencing the latter in TCJ #233 in relation to David Boring so we do have evidence that he knows the phenomenon.)

A lot of people here have pointed out that dynamic between disaffection and really tumultuous emotional moments as what makes the book resonant for them. My recollection of Enid had been “archetypal disaffected grumpy teen.” I actually didn’t get that much at all this time, and I think it’s the way the conversation here has underlined the distinction between Barthian disaffection – which is really a kind of psychic paralysis that bears only a metaphorical relationship to “real” experience – and pop-cultural ironic distance, which is a pretty common subject position. I admit the latter is there, but it didn’t feel “disaffected” in that light. It’s more a cultivated disconnection –“this thing that matters to them? It so does not matter to me,” – and it felt entirely self-protective rather than truly detached. She didn’t feel like she was “searching for an identity” and coming up “nowhere.” She felt like she was fearing adulthood and coming up adult anyway.

I was looking for unreliability, and suddenly it was everywhere: is she really detached, or is she just pretending to be? Did that thing really even happen or is she just making it up? Her stories were always obviously, well, embellished, but this time, looking specifically for places where her narrative might be unreliable, suddenly they felt even more fictional. The trick seems to be that if it happens in dialogue with Becky, we’re probably supposed to think it happened. If Enid tells it, maybe it did, maybe it didn’t. The images give us clues what to hang onto and what to read as hyperbole … from there, Enid’s propensity to exaggerate and overdramatize seemed to be the thing she outgrows over the course of the story, not her ironic detachment or disaffection. She stopped protecting herself with stories, hanging on to the way when you’re a child you can fabricate imaginary events, escape into your imagination in a way that you can’t do as an adult.

But maybe it’s more unreliable than that. Maybe the scenes with Becky really aren’t the tell: Melorra by all conventions SHOULD be lying (“I’m in a commercial”, OMG Carrie’s face) but both are backed up by my previous logic, so maybe instead that Lynchian grotesque moment when you see the tumor actually is the moment where you’re supposed to say “oh, wow, all that stuff is unreliable.” Maybe there’s a level of unreality that we’re not even touching on.

Either works to some extent, and both are kind of fun, – but is not being sure whether the narrative is true or imagined really what it means to have an “unreliable narrator”? I guess it is, in a simple sense. But it’s more than a puzzle in the best literary fiction that uses the device: it’s a veil that can’t really be lifted to ever determine what’s true and what’s not . The unreliability stays in play and becomes a metaphor, often, for fiction itself, for how narrative and belief get tied together with merely some typographical characters on a page. Here it could become a metaphor for how narrative and belief get tied together with typography and image, but instead it’s really just a metaphor for adolescence itself. Whether or not Enid’s telling the truth about ANYTHING, the issue resolves when she grows up. You still end up with this basically sweet story about letting go of childhood (bracketing Noah’s reading for now), and the only real difference is at the level of close reading and whether Mark thinks I am making things up. (Pfft.) The jury’s still out on whether unreliability becomes a metaphor for the work that comics do in David Boring: it seems intuitively on tonight’s first ever quick read-through of that like it might.

The adult male thing is just a lot more complicated. There are a lot of adult males: the comedian, the pedophile ex-priest, Bob Skeetes, John Crowley, Enid’s dad, ‘David’ Clowes, Norman. Jury’s definitely still out on that.

I think Uland’s question — why is that creepy? — is a good one, and figuring out the answer might help me clarify some things about the book…but whether I’ll do that or not is unclear. I really just don’t find it all that interesting, honestly.

To respond to your point about what’s wrong with Enid as a fetish object from Shaenon’s post….I think it depends on what the fetish is, and how it works out in the story. As I said, the fetish here seems to be sadism; that is, he seems to be getting off on controlling Enid, or on having her be empty and filling that space. As for what’s wrong with that…I mean, among other things, it’s really boring; it’s kind of what all the creator guys are into, you know? And it’s also just really unpleasant if you believe that denying women (or anyone) their humanity is morally wrong.

Obviously, fetish qua fetish isn’t a deal breaker for me. I just think Marston is a lot weirder and more thoughtful in his obsessions.

Already plenty of comments (that’s the problem of living in a different timezone), so I’ll only throw in two of my reactions reading all that’s been said here.

First, the aesthetic choice of the blue tinge. Noah finds it “ugly”, without giving it any more thought, which I think is a little too easy and definitely not satisfying. The blue tinge adds a coldness to Clowes’ already much-controlled line, and strengthen the distance and alienation he evokes in “Ghost World”. There’s a kind of dusk pervading all the pages, as if things were in this twilight moment where shapes are indistinct and unsure. It’s not there to be pleasant. It’s not there to be aesthetically pretty. It’s there, because it suits the story and its atmosphere.

My second reaction is a little bit along the lines of Shannon Garrity’s text, about your view that Clowes merely depicts a teenage girl with a thirty-something guy’s personality. I know I’ve never been a teenage girl, it’s pretty much unknown territory to me, but there’s something that resonates in “Ghost World” with my memories of being an alienated teenager, and the unease I felt towards the world around me. (then again, I’m European, so who am I to say anything about it?)

Reading what has been written on that subject, I have the impression that you are criticizing Clowes for not using the usual stereotypes of teenage girls. (“What? They are not girly, they don’t talk about boys all the time, they don’t worry about make-up and put up posters of the latest boys band? That means Clowes is wrong, he doesn’t know shit and his characters are not believable.”) I don’t believe thirty-something male critics are better judges on accurate teenage girl characterizations than thirty-something male writers — but maybe that’s a cheap shot.

Hey Xavier. Well, I may or may not be qualified to judge the accuracy of the portrayal of teen girls. However, I did read all of Twilight, and I can say categorically that it’s infinitely superior to Ghost World.

And yeah, I’d rather listen to Justin Timberlake’s last record about a million times than slog through Clowes’ ugly blue-green aesthetic choice again.

Just to be clear; I’m not saying that reading Twilight gives me any special insight into teen girls.

I am saying that the speed with which defenses of Clowes characters seem to wind up with dismissals of and/or sneering at the intellect and culture of teen girls seems to me telling. Not to mention familiar and depressing.

Wow, this is a great discussion, and it’s interesting to see just how different people’s readings of Ghost World are. Which is great, and for me at least is to Clowes’ credit.

Just a brief note re: the Shrag/Clowes discussion. Noah, at the risk of repeating myself, you seem to be allowing for Shrag what you don’t for Clowes. You buy into her emotional reality, but dismiss his as ‘glib’. Your preference for Shrag’s voice is understandable enough, but its correlative here seems that you’re unwilling to allow for the possibility that Clowes is also investing his characters with emotional honesty.

Seriously, this is what makes Clowes great to my eyes. He is one of the subtlest cartoonists I know, revealing what really moves his stories only to the attentive reader, for whom it becomes all the more powerful.

Great discussion here, everybody. I don’t really have much to add, since I haven’t read the book in years, but what everyone is saying here is definitely making me rethink my high opinion of it. I did originally read it at probably the perfect time, as Richard said, when I was about 21 and just starting to grasp adulthood (does that make me a late bloomer?), and it seemed like it really connected with me, that sort of archetypical disaffected teenager attitude and nostalgia for a youth that wasn’t all that long ago. The whole “Clowes as Enid” aspect didn’t occur to me at all back then, so reexamining it in that light is kind of fascinating. So, neat.

Yeah, like I said, not much to add here, but everybody else has done some good talkin’. You guys are awesome.

Aw…you’re making our bytes blush….

Y’know, Caro, upon re-reading I’m not findin’ much I disagree with in anything, and you caught some stuff I missed.

(That’s all. I have nothing else to add.)

I think you’re uncomfortable with straight, white, middle class sexuality, Noah.

I mean, I can see no reason why the depictions of fetish object in all the gay manga you love shouldn’t be creepy, if Clowes’ is.

Really, we haven’t even established that Enid is a fetish object.It seems like you think so precisely because Clowes tries to humanize her ( or make her seem real), but fails in certain revealing ways. I don’t buy it.

I think Clowes wasn’t overly concerned with representing a universal teen girl experience; the character of Enid is obviously a kind of frankenstien of Clowes and ideas he has about his wife. I know that her teen experience informed the character. It’s a really interior, intimate characterization. She lives in a dream world, full of character types and incident. He didn’t set out to present an accurate portrait of the norm, but a love letter to the little particulars relevant to his world-view.

I don’t really like the straight white middle class sexuality expressed by Clowes towards his ideal/despised teen hearthrob, no.

On the other hand, I love Pride and Prejudice. Its straight, its white, its certainly middle class. Maybe it doesn’t count because it’s British?

Because it’s post-ironic, or something. I don’t know.

It’s interesting to note a core difference between Barth and Clowes relative to the creation of their two books: the former was 25 or so when he wrote about “his” mid-life crisis and the latter, as mentioned, was middle-aged writing about “his” teen-life crisis. I think Noah expresses the position that Barth warns against in his preface, seeing the core dramatic theme as symptomatic rather than emblematic. I’d suggest that just because a problem is most readily apparent in a particular class, it doesn’t mean that the problem isn’t foundational of contemporary existence. Maybe I’m too much of the “unexamined life isn’t worth living” type, but I can’t see Becky’s ability to function as any real solution to Enid’s problem. Relatedly, although it’s been awhile since I read any of Schrag’s comics, Noah’s description reminds me when I didn’t have an interest in reading any more of them. She’s caught up within the prevalent order of things, dealing with the problems of fitting in to that, not with something like Enid questioning our zero-level ontology.

“reminds me WHY”

Noah: “Perhaps the most emblematic moment in the book, in this respect, is when Enid meets (a thinly disguised) Clowes himself… Clearly this is supposed to read as self-effacement on Clowes’ part. But I wonder. Enid’s initial fascination (which is in part sexual) is certainly a fairly familiar creator fantasy (“she loves me for my art!”) But even more than the enthusiasm, it seems to me that the disappointment is a kind of sublimated self-aggrandizement.”

I think you’re shutting out the obvious intent of this passage. Clowes manipulates the reader’s reactions: when Enid announces her interest in “David Clowes,” some of whose comics the obnoxious hipster character showed her, your average reader cringes and fears that Clowes is slipping into a self-aggrandizing fantasy, as I did. Maybe it was different for you (“Aha! I’m onto him!”) Her initial fascination is undercut by the scene where she gets a look at Clowes, which is not only funny and deflating, but his leering, nasty appearance brings the problem of where he stands in relation to these characters to the forefront.

(And it’s not a “thinly disguised” Clowes, it’s Clowes. Enid gets the name wrong because she’s only had a glancing exposure to his work.)

Noah: “Indeed, the page reminds us subtly that it is Clowes calling Enid into being; we see her from his perspective first, and only then can she see him.”

Enid is seen from Clowes’ perspective at the moment she gets a look at him, but that’s not the first time we see her. More importantly, we see Clowes through Enid’s eyes, and his cameo reveals the way he, and his interest, would and must look to her. He is defined by her perspective at that moment. Now, it’s true that the spot lighting and setup of his appearance reminds us (in an ironically shabby fashion) that he is the author and “ruler” of this little universe. But in creating Enid, he’s experimenting with a point of view which ruthlessly diminishes him.

“This is, to the best of my recollection, the only time in the narrative that Enid expresses an unironic connection to, or enthusiasm for, any piece of contemporary pop culture… Enid’s initial fascination (which is in part sexual) is certainly a fairly familiar creator fantasy (“she loves me for my art!”)… We never learn what she likes about faux-Clowes, or what it is in his books that inspires her.”

I think Clowes is making an accurate observation of the kind of effect his work has, or had at that time, as a kind of countercultural token. I’ve seen young (college age) women react that way to his work and to cartoonists of his ilk, not necessarily “I’m in love with him,” but an impassioned reaction that this spoke to their experience and wasn’t like the other media options out there. Clowes has told a story in interviews about how some teenage girl ran away from home and appeared on his doorstep, and how the meeting that ensued was awkward not only because he didn’t know what to say but because she seemed to realize very quickly that she had fantasized a mutual understanding that wasn’t there. The intended effect of his kind of cultural product, particularly at that time (an obscure medium, its artifacts passed along by those “in the know”) is shot through with a lot of illusion and idealization.

See, there are ways that an artist can make a problem with himself or with what he’s trying to do in a given work part of the problematic richness of that work, by deliberately encouraging us to consider it. In that scene, Clowes is addressing and spotlighting the creepy potential in his being a middle-aged man writing about teenage girls, as much as you’re attempting to do. You’re using a kind of aggressively obtuse literalism (“this proves that Clowes is a pervert”), and you’re asking us to accept an implausible reading: that the setup for that encounter is truly about Clowes glorying in Enid’s desire for him, that the encounter is about Clowes glorying in his domination over Enid, and that any seeming artful intent is merely a chameleonlike deception that permits him the free exercise of his molesting, drawing hand unchallenged by any but you.

Why do you think it’s unchallenged by anyone but me? Lots of people don’t like Clowes’ work. Some of them even wrote for this roundtable.

Does the point of view ruthlessly diminish him? Remember, Enid’s name is Clowes’ name scrambled, right? And I don’t find your argument re: Clowes as countercultural icon especialy convincing. Not that his work doesn’t sometimes evoke strong emotions…but again, the *only* time we see Enid unironically embrace a piece of pop culture is this time. That seems overly convenient to me.

Also…if Clowes is ruthlessly diminishing himself, why does that diminishment give you an excuse to herald his artistry, exactly? And if diminishing him is the goal, why the resistance to a reading that does that? I’d agree that Clowes is thinking about and playing with the cult of genius — but I don’t think that you’re supposed to come away from that play thinking, “gee, he’s not a genius.” Nor does your insistence that, no, really, he is a genius make me question my reading, particularly.

I didn’t say Clowes was a genius. I said the elements you’re criticizing are part of his design, so it’s no longer sufficient to merely say that Clowes’ being a middle-aged man writing about teenage girls is creepy when he makes that an aspect of the work.

Now, I could understand someone finding Enid’s brush with Clowes unconvincing as a piece of pre-emptive criticism. Just because he did it doesn’t let him off the hook. But… it doesn’t let him off the hook. He salvages the reader’s faith by showing her disinterest in him, but he’s forcing the question of what he’s doing with these characters, why he’s interested in them.

He could have drawn himself as another middle-aged sad sack in order to have the girls reject him; could even have played for sympathy that way. There are cartoonists who do things like that. So why does he draw himself as not only unattractive but as leering at Enid, and into the camera?

“Remember, Enid’s name is Clowes’ name scrambled, right?”

And so he’s signaling the reader that she is an authorial surrogate. Again, you don’t get past pointing that out. This identification becomes difficult to accept straightforwardly since Clowes likely didn’t lose his virginity to a male reggae fan, or torment a well-mannered boy who was in love with him with visits to sex shops.

Along those lines, I’m not convinced by your assertion that Enid is completely unlike any teenage girl. Judging from other material on this site, I think this is more a matter of genre preference. I don’t doubt that many teenage girls experience a rapturous identification with Twilight and girl’s manga that they would not with Ghost World. But you write about those genres thoughtfully, which makes your inability to do so here even less convincing.

The logic behind the girls’ behavior is supposed to be mysterious, and so it’s not exactly like life, but it’s about life, the way Notes From Underground is about an eccentric character who the author, provocatively, insists is out there and is necessitated by the way things are.

“And I don’t find your argument re: Clowes as countercultural icon especialy convincing.”

I wasn’t defining him as a counterculture icon- although I think he was before the lit-comics boom, but only according to the strictest definition and to a tiny subset of people; nothing like R. Crumb or Timothy Leary. I was talking about the way that kind of comic worked as a countercultural token at that time: an obscure piece of work, passed along by those “in the know,” retained fetishistically by its owners, a secret signal from the author to a tiny group of insiders who “understand” and feel “understood”. Enid’s initial reaction to his comics is credible to me because I’ve observed it, but it also so obviously plays with the reader’s expectations of who the author is and what he hopes to accomplish with his work that it’s dunderheaded to take it as Clowes indulging his desire.

“the *only* time we see Enid unironically embrace a piece of pop culture is this time. That seems overly convenient to me.”

The doll she leaves at her street sale… Smile and a Ribbon… and let’s not forget Clowes emphasizes that Enid has only had a glancing encounter with his work. Your characterization of her engagement with her milieu as “ironic” also deserves a closer look; she has an ecstatic quality.

Again, you are asking us to accept your grudge-reading that Enid’s brush with Clowes only appears self-deprecating as a cover while based on the subtle coding you detect he truly drew it to glory in his character’s devotion to him and his mastery over her. A reading that Clowes is exactly the leering troll he draws. That’s not credible because people like that tend not to have such an unforgiving perspective on themselves. Moreover, even if Clowes “is that,” the debate is still about the work. He still deliberately created an encounter in which he is a menacing, pathetic character in relation to his creation. Thus the encounter is not a straight-up expression of desire but a consideration of where he stands in relation to a character who enacts a way of being and dissatisfactions that are larger than that sense of his relation to her. But that already seems like more work than is justified to deal with the reading that Clowes is a pervert because he drew himself as a pervert.

“The doll she leaves at her street sale… Smile and a Ribbon… and let’s not forget Clowes emphasizes that Enid has only had a glancing encounter with his work. Your characterization of her engagement with her milieu as “ironic” also deserves a closer look; she has an ecstatic quality.”

The doll is childhood nostalgia, not ecstatic identification with current pop culture. Enid interacts with pop culture like a middle aged guy; all about her childhood obsessions.

And I really don’t have a grudge against Clowes. I don’t like his work for the reasons I’ve articulated. If you do, that’s fine. And it’s not about who Clowes really is or isn’t. I have no reason to think anything at all about his morals or interests outside of Ghost World itself. He figures himself in the comic though (and not just as a character), and I think it’s entirely reasonable to think about that and question it.

Oh…and of course it’s part of his design. He’s very clever. He’s definitely playing with the relationship between himself and his character quite consciously, thinking himself as her, as loved by her, as creeping her out. That works through her other relationships with other older male characters as well. The question for me is, does his consciousness of what he’s doing mean he’s not doing it? You think it does, I’m not convinced. Intent and self-consciousness sometimes include critique…but sometimes they’re just part of the pleasure. Especially when the pleasure is mastery.

So basically, although you don’t judge Clowes’ morals, or his interests outside of comics, and you are merely disinterestedly questioning his work, he is the devil.

“The doll is childhood nostalgia, not ecstatic identification with current pop culture. Enid interacts with pop culture like a middle aged guy; all about her childhood obsessions.”

I think Enid’s quest for authenticity is completely in line with the bohemian strain of youth culture in the 90s. Her ecstatic side shows up in her interactions with her environment (the eccentric local characters, “two really ugly people in love like that…”) And in whatever sense Clowes might identify with her, I don’t see how her behavior in Ghost World supports the reading that she is not a credible teenage girl, that she is a vessel for the artist’s opinions, and that she never develops a personality and identity.

“He figures himself in the comic though (and not just as a character), and I think it’s entirely reasonable to think about that and question it.”

As do I. I’m saying you’re not doing that, but seizing on all examples of the kind of self-examination and self-doubt that marks artistic seriousness as evidence of the artist’s faults in a blinkered, vindictive, redundant way that fails to pursue its leads in any direction. It doesn’t seem like you’re being contrarian so much as you’ve got it in for this genre to the point that you’re not really performing acts of criticism.

You’re doing a meta-ironic thing by accusing me of making personal attacks by personally attacking me, right? Very clever; Clowes would be proud.

If pointing out that someone is confusing personal attacks with criticism is an ethically incoherent personal attack, that’s allowing a very limited scope of engagement. And are you saying you don’t make personal judgments about artists…?

Oh, come on. You’re saying that I have some personal grudge.

I think it’s hard to separate criticism of art from criticism of the artist, honestly. Especially where someone like Clowes is deliberately conflating them.

I don’t really take offense at you doing the same to me. I just think it makes you look a little silly, is all.

“The fetish here seems to be sadism… [Clowes] seems to be getting off on controlling Enid, or on having her be empty and filling that space… It’s really unpleasant if you believe that denying women (or anyone) their humanity is morally wrong.”

I’m saying that’s a bit much in response to the phenomenon of an author identifying with his character. Really it’s a very constricted notion of what an author can do, what teenage girls can be like, and a denial of the common humanity that literature is about… applied consistently, it would be. Yeah, I think it’s weird, and personal.